Pablo Picasso didn’t keep still: his art advanced from one phase to the next, as he developed and refined what he wanted to convey and how he wanted to communicate it to the world. This temperament was similarly expressed in the restless changing of his personal look. When he first arrived in Paris from Spain in 1900, at age twenty, he lived in poverty; over the course of the next few years, he would pay for dinner at Le Lapin Agile, the Montmartre cabaret, with his work. He dressed the “artist” part in mended overalls, fisherman sweaters, and shapeless work jackets: he was intense and serious about making a name for himself as a laborer in art. In 1919, while working in London on designs for a Ballets Russes production of The Three-Cornered Hat, he fell in love with the style of an English gentleman. He visited Savile Row’s finest tailors with Virginia Woolf’s brother-in-law, the art critic Clive Bell, and bought three-piece suits, which he wore perfectly with pocket handkerchiefs, brogues, and a bowler hat. When in Monte Carlo with Serge Diaghilev in 1925, after collaborating again with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Picasso looked the part in white slacks and navy blazers.

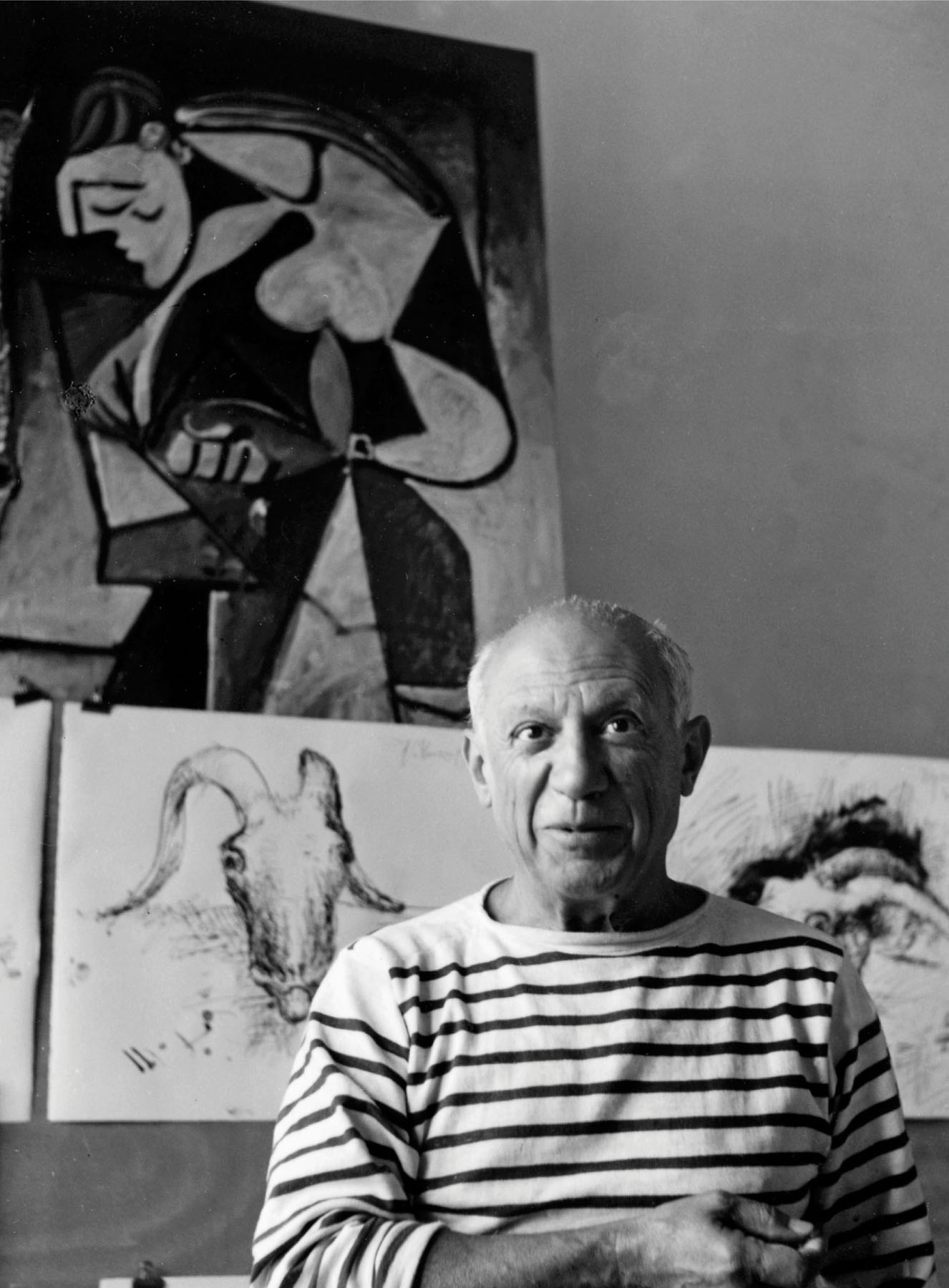

Getty Images: Robert Doisneau/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

Picasso in his workshop, Vallauris, France, c. 1952.

Picasso’s looks were numerous: F. Scott Fitzgerald–esque Oxford bags and stylized flat caps, sexy-beast black shirts undone to mid-chest, Breton T-shirts, chino pants, and espadrilles; 1950s toweling polo shirts and shorts, striped shirts clashing with plaid trousers—and sometimes, later in life, striding around shirtless: larger than life and in charge. And he loved hats: Peruvian knitted hats with pom-poms, sun-shielding straw toppers, and stiff, classy homburgs. And more: dress-up matador hats, Vietnamese conical hats, and American Indian feathered headdresses—Picasso wore any and all of these for a laugh, and quite often while smoking a cigar.

The beret, traditionally worn by Basque farmers, would become a Picasso trademark, both in his wardrobe and as a motif he painted time and again. His accessory of choice takes center stage in Woman with Red Hat (1934), Women with Beret and Checked Dress (1937), Marie-Therese in Blue Beret (1937), and Man in Beret (1971). Another Man in Beret was one of Picasso’s first known portraits, made in 1895 when he was fourteen; it shows off his early virtuoso skills. Just how influential Picasso’s beret-wearing turned out to be is evident from attendance records at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art, which reveal that after two Picasso exhibitions staged in the 1950s, employees found lost berets more than any other personal items. As the ICA explains, “He wore one and everyone was trying to copy him.”

In 1903 when Picasso was staying in Boulevard Voltaire, he was so poor he shared a bed, notebook, and top hat with his friend the poet and critic Max Jacob.

Historically a beret was worn by rebels, radicals, and intellectual bohemians, and Picasso adopted all of these personae in his lifetime. He signed up with the French Communist Party in 1944, and throughout his life he would freely donate money to its causes, along with creating profound imagery that reflected his philosophical concerns. Picasso’s most famous public art piece, Guernica, was commissioned for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair in 1937. One of his most striking statements on war, human suffering, and agony, the painting has become a “symbol of resistance,” as the Tate Gallery points out. Over time, Picasso’s politics have been explored and evaluated as much as his art. A Spectator feature in 2018 described him as “rich as Croesus,” but he possessed the ideologies of an activist. The beret was a fashion echo of his principles and temperament, part of his brand and sensibilities.

One whom some were following was one who was completely charming. One whom some were following was one who was certainly completely charming.

—Gertrude Stein, Picasso, 1912

Getty Images: Pierre Guillaud/AFP/Getty Images

The model Katoucha wearing an evening dress inspired by Picasso for Yves Saint Laurent’s 1988 spring/summer haute couture collection, January 1988.

Designers have long been captivated by Picasso and his wide-ranging oeuvre. In 1935, Elsa Schiaparelli was moved by his Hands Painted in Trompe-L’oeil Imitating Gloves (Picasso painted real hands and Man Ray photographed them) to create her legendary black gloves with red python nails. In 1940, Bergdorf Goodman’s fashion windows displayed seasonal collections together with some of Picasso’s paintings as a preview for the exhibition Picasso: Forty Years of His Art at the Museum of Modern Art. The works included his Rose Period Buste de Femme, matched with a silver fox jacket and a gold lamé dress, and Nude in Gray from the Blue Period next to a long cape of baum marten fur. In 1944–45, the great Hollywood costume designer Gilbert Adrian designed an ankle-length dress he called Shades of Picasso, inspired by the artist’s blocky color and forms in his cubist work. In July 1979, Yves Saint Laurent’s winter couture collection included a tribute to Picasso’s alter ego—a Harlequin dress in pale pink satin and black-dot tulle with ruffled collar and cuffs. Prada’s geometric-patterned bags of summer 2017, Oscar de la Renta’s resort 2012 Picasso newsprint dress, the distorted abstract faces on knitwear at Jil Sander 2012, and the double-faced makeup on the models at Jacquemus in autumn/winter 2015—all have been steered by Picasso’s imaginative lead.

Picasso himself was no stranger to the decorative arts. In 1955, he worked with the American company Fuller Fabrics on a Modern Masters collection, producing textiles with names such as Rooster and Fish that were made into daywear; in 1956, he designed a range of furnishing materials, one called Turtle Dove, with the same company. He also collaborated with sportswear brand White Stag in 1962—among the collection were vinyl anoraks printed with bulls and corduroy ponchos made from his Musician Faun pattern. Ads for the line, in keeping with his egalitarian and revolutionary standards, told potential buyers, “Can you afford a Picasso? If you have thirty dollars you can!”