Of all artists, Marcel Duchamp may have most profoundly inspired fashion. He spent his career analyzing the world around him, constantly expressing himself in varied ways. After his modernist painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) made him famous and caused a sensation, he began experimenting with a new creative approach, the “readymade”—a name Duchamp invented. A method of choosing commonplace objects and turning them into art, this process enabled him to scour for inspiration in every unexpected nook and cranny. Beginning with his famous Fountain urinal in 1917, he went on to explore the validity of bottle racks, birdcages containing marble blocks, a miniature French window, and, of course, a bicycle wheel as expressions of artistic intent. This Dadaist take envisioned the world with satirical irony.

It’s hard to avoid seeing parallels in the collections of Georgian designer Demna Gvaslia. In 2017, he declared that his label, Vetements, would only produce clothes “as a surprise” when he felt like it and dipped out of the seasonal catwalk system. Exploiting the appeal of the unexpected, he has shown nonsensically outsized hoodies that look impossible to wear, as well as bright yellow T-shirts branded DHL (the transport company) that cost over $200; all have been instant hits. Jeremy Scott at Moschino has similar affinities, creating clothes with McDonald’s fast-food logos and Happy Meal handbags that have the finish of couture.

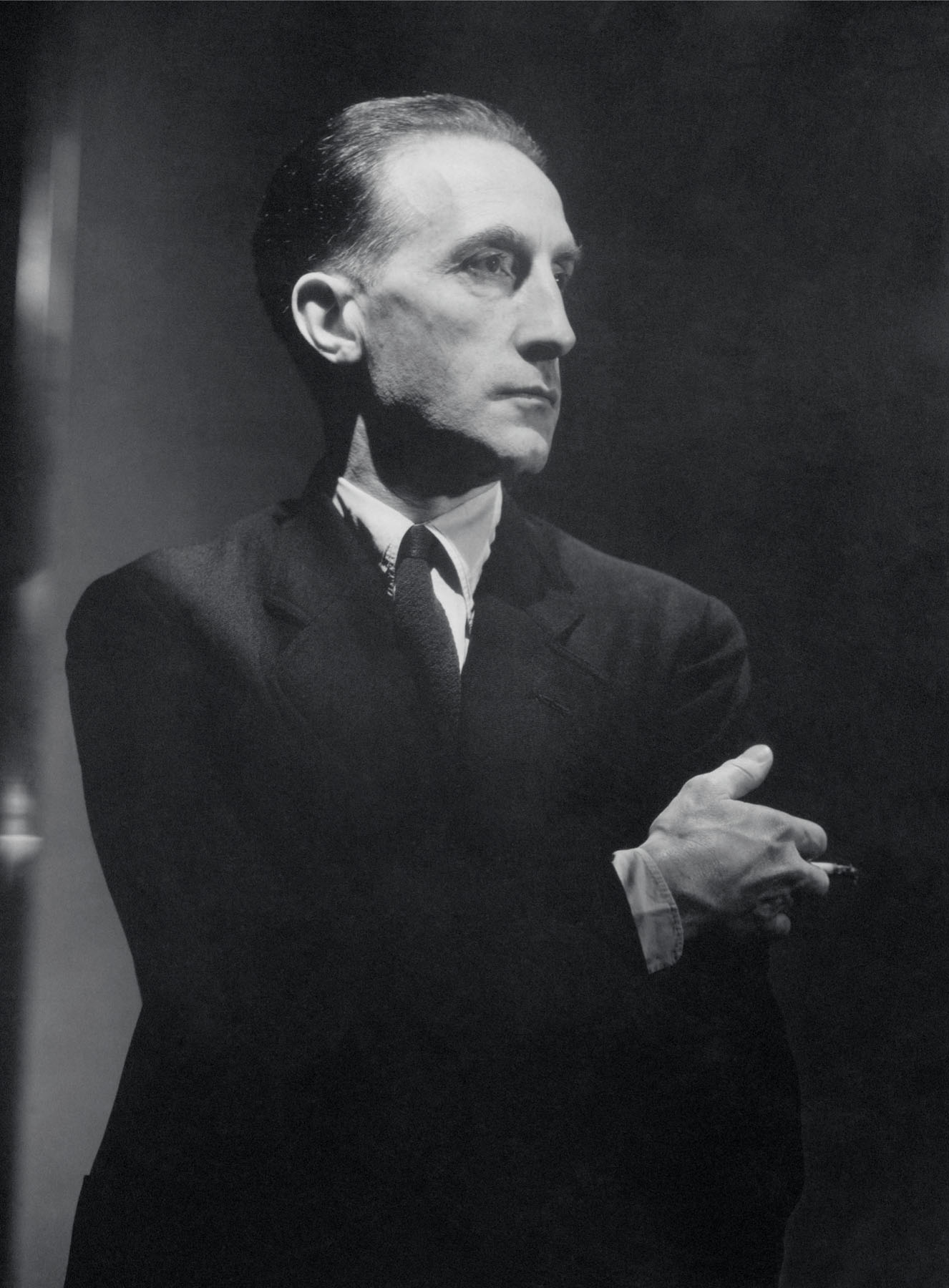

Getty Images: Bettmann

Marcel Duchamp, New York City, February 1927.

The unanticipated makes waves in fashion, and Duchamp showed the way. Humor and contemplation are at the heart of what he did: putting facial hair on da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in 1919 in his L.H.H.O.Q. piece is akin to Gvaslia reinterpreting the old masters of fashion as creative director at Balenciaga. Marc Jacobs has said that Duchamp’s Mona Lisa is his favorite artwork. For a show backdrop in 2014, Karl Lagerfeld took a leaf out of Duchamp’s book, decorating a lavatory door with a cartoon of Coco Chanel and calling it Door II.

Duchamp’s own look was that of a dandy. He wore a raccoon fur coat in 1917, at the time the very pinnacle of fashion statements for the flamboyant, although on a day-to-day basis he preferred a smart white shirt and tie. He explored contradiction and identity in his art: In 1921, he debuted his female alter ego Rrose Sélavy—a pun that in French sounds like Eros, c’est la vie. Man Ray, Duchamp’s friend and partner in art-pranking, photographed “Rrose” for a readymade that was based on a perfume bottle created in 1915 by Rigaud for its scent Un Air Embaumé. Duchamp’s scent was called Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath, Veil Water); the label with Man Ray’s image showed him dressed in a hat, frock, and sultry eye makeup. (The bottle became part of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s art collection in the 1990s before being sold.) Sélavy made a number of appearances, for example, as a mannequin wearing a man’s hat, jacket and tie at the 1938 Surrealism Exhibition in Paris. The piece was titled Rrose Sélavy in one of her provocative and androgynous moods, with initials RS doodled on the naked crotch.

Things that are not what they seem is an enduring motif in fashion as it was for Duchamp during his lifetime. Dada confronted society’s comfort zones, and we can see designers who challenge stereotypical norms of beauty as following this creative line. Originators such as Margiela, Bless, and Comme des Garçons have sought to recalibrate the potential of a clothing label, gently moving the goalposts of consumption. The awkwardness of a white-painted canvas sneaker that cracks with each step makes this Margiela design a classic. The design duo Bless in 1997 created wigs out of old fur coats for the house; it didn’t look at all like proper hair. Ann Demeulemeester delivered Duchamp’s message unequivocally when she soundtracked the beginning of her 2008 autumn/winter catwalk show with a recording of an interview with the artist in which he “talked about the durability of the nonconformist spirit,” wrote Tim Blanks on Vogue.com.

I don’t care about the word “art” because it’s been so discredited. There is an unnecessary adoration of art today. But I’ve been in it and want to get rid of it. I can’t explain everything that I do.

—Marcel Duchamp, BBC Television interview, 1968

Getty Images: Lusha Nelson/Condé Nast via Getty Images

Duchamp, photographed by Lusha Nelson for Vanity Fair, 1934.

Duchamp himself said in 1957, “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.” The act of putting on a piece of designer clothing makes fashion multidimensional, and when the clothing in question is innovative, then predictability in other forms is tested in small ways, too. Duchamp wanted his work to please the brain and not just the eye, explaining, “I was interested in ideas—not merely visual products. I wanted to put painting once again at the service of the mind.” The crossover of fashion and art is simply about developing ideas and trying new things.

In 2012, designer Hussein Chalayan and artist Gavin Turk produced “4-minute mile,” a musical track inspired by Duchamp’s spiraling Rotary sculptures from 1925, on which Turk’s conversation about art with Chalayan is recorded. The project defied expectations, and Duchamp would have approved. In 2017, Virgil Abloh commemorated the hundred-year anniversary of Urinal with an Off-White hoodie signed R. Mutt, duplicating the inscription on Duchamp’s original readymade. At the other end of the spectrum, Philip Colbert of the Rodnik Band made a literal urinal dress—three-dimensional and covered in sequins—for his 2011 collection. Colbert exclaimed, “A model wore that dress on the red carpet. It just created a sense of shock—people were just like ‘oh my god, she’s wearing a toilet dress.’”