Salvador Dalí, surrealism, and fashion go hand in hand in hand. The make-believe consciousness of illusory art and the fantasy of designer wear engage in a reflective and reflecting relationship. Dalí’s first illustration for Harper’s Bazaar in 1935, Dream Fashions, depicted “imaginative suggestions for this summer in Florida.” He suggested to readers that coral corsets, a face mask of roses, and a pair of glossy leather stockings might be interesting wardrobe staples for the beach. Dalí’s inventive approach was always looking to the future. In a January 1939 editorial for Vogue titled “Dalí Prophesies,” he predicted that “jewels of tomorrow will wind up and come to life, like exquisite mechanical toys. Bracelets creeping on arms, diamond rivers flowing around necks, flora and fauna clips opening and closing.”

In 1950, when Christian Dior asked him to create the “costume for the year 2045,” Dalí drew a ruched silk dress with pannier draping and a breast on either hip, decorated with embroidered silver sun faces. It was accessorized with a burgundy velvet crutch and a turban hat with an insectoid antenna sprouting from the forehead. This marvelous outfit in some way prefigures the 1997 Lumps and Bumps collection by Comme des Garçons fifty years later. Dior had already manifested his admiration of Dalí in 1949 when he created a Dalí Dinner Dress, featuring a black-and-gold brocade leaf print over a halter-neck bodice and gathered skirt. It’s as understated as the 2045 dress is not, but nevertheless plays with detailing that echoes the spirit of Elsa Schiaparelli, who had been Dalí’s leading fashion collaborator.

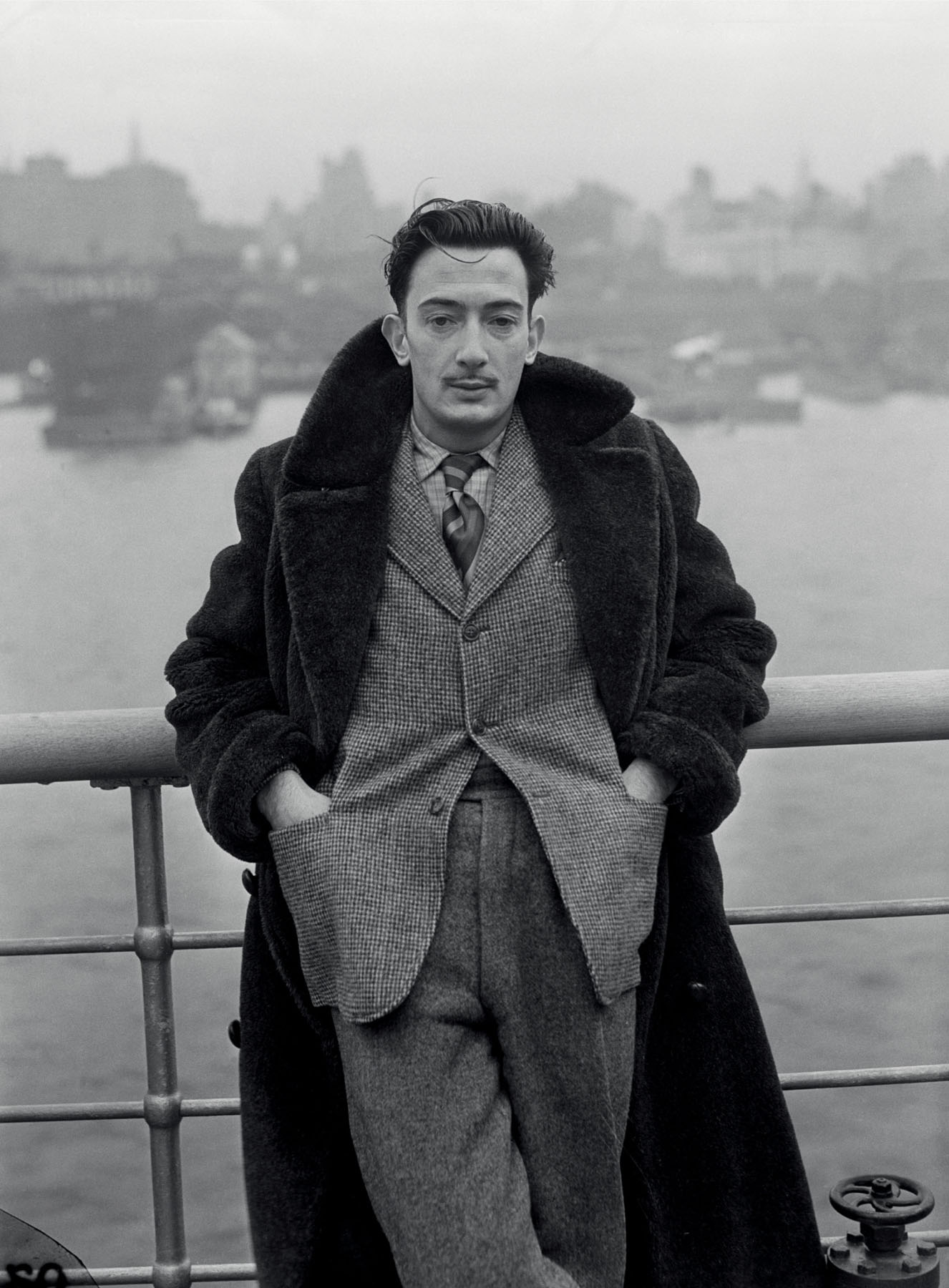

Getty Images: Bettmann

Salvador Dalí on the deck of the SS Normandie, New York City, December 1936.

Getty Images: Ullstein Bild/Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

Inspired by a drawing by Dali, Elsa Schiaparelli designed this shoe-shaped hat and jacket with an appliqué in the form of a lip in 1937.

Dalí suggested that the white organdy Lobster Dress that Elsa Schiaparelli designed in 1937 would look best spread with mayonnaise; the Italian couturier declined to add this final flourish to the gown.

When Dalí was exhumed in 2017 as a result of a paternity case, his mustache was still intact, arranged as always pointing upward.

Schiaparelli and Dalí together had attempted to forecast the future with an array of radical designs, including the famous Lobster Dress and the black wool shoe hat of 1937 and the silk-and-rayon trompe l’oeil–print Tears dress of 1938. The designer and artist were evenly matched forces with futuristic philosophies; in June 1932, Janet Flanner, the Paris correspondent for The New Yorker, wrote, “A frock from Schiaparelli ranks like a modern canvas.” Dalí’s concepts worked readily with her innovative designs.

Born in Catalonia, Spain, in 1904, Dalí began to attract notice in 1922 as an art student in Madrid, where he studied at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando until he was expelled in 1926. When he arrived, he wore his hair long and strode around in knickerbockers accessorized with silk socks, a cape, and a cane. He was a glamorous dresser all his life; however, he learned at the academy to merge his sartorial showmanship with the elegance of a well-tailored suit and to pomade his hair. He adopted and wore this uniform for the rest of his life, looking like the epitome of an English gentleman. He had a variety of signature suits—from the traditional tuxedo to three-piece pinstripes and tweed—always worn with a tie and pocket square. Against this look he juxtaposed the madness of his trademark mustache, which he never tired of twisting into that celebrated upward spiral.

WireImage: Antonio de Maraes Barros Filho/WireImage

A model in an orange sequined lobster dress, Maison Martin Margiela haute couture fall/winter 2014–2015 presentation, Paris Fashion Week, July 2014.

When he and his wife, Gala, came to New York for the first time in 1934, they got off the ship in matching fur coats, his shrugged over a suit. They often coordinated outfits; for example, wearing matching unisex wide jersey pants when at the ocean. For visits to their cottage at Port Lligat in Cadaques, Spain, his favorite leisure wear was a blue and brown cowboy shirt worn with a red barretina—a Catalan hat that looks like a paper bag. This was as casual as he got. In the 1960s, Dalí began wearing a favorite panther-skin coat accessorized with his pet Colombian ocelot, Babou; in the 1980s, he wore an ocelot coat.

When Dalí chose to make an entrance, he did it magnificently. In 1934, at the Bal Onirique party in New York, given in his honor by the socialite Caresse Crosby, he wore “a pair of spotlit breasts supported by a brassiere.” In 1936, he wore a deep-sea diving suit and helmet, accessorized with a billiard cue and a pair of Russian wolfhounds, to the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His outfit indicated that he was “‘plunging deeply’ into the human mind,” Dalí explained; however, he ended up unable to breathe and had to discard the helmet. The same year he took part in an exhibition at the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris, showing his Aphrodisiac Jacket, which was covered in shot glasses. On display also were pieces by fellow surrealists, including Man Ray’s blanket-wrapped sewing machine and Meret Oppenheim’s fur-covered teacup and saucer. But only Dalí wore his art to parties, making a modern art-meets-mode statement. He would use the Aphrodisiac Jacket again to fuse art and fashion when he was commissioned to design Bonwit Teller’s windows on Fifth Avenue, presenting a model with a head of roses standing between a red lobster telephone and a chair decorated with the jacket.

Don’t bother about being modern. Unfortunately it is the one thing that, whatever you do, you cannot avoid.

—Salvador Dalí, Diary of a Genius, 1964

Dalí’s subversive influence on fashion began with his own work. Along with the pieces he designed with Schiaparelli, jewelry was another forte. With New York jewelers Alemany & Ertman he created a brooch called The Eye of Time as a gift for Gala in 1945. Over the years it has reappeared on many catwalks: in 2016, Alessandro Michele for Gucci showed it on men’s suit pockets, and the relaunched House of Schiaparelli featured it on dresses in its autumn couture show in 2015. His 1949 Ruby Lips brooch, created with real rubies and pearls for teeth, has become a classic Dalí motif, not least because it echoed his Mae West Lips Sofa sculpture from 1937. Lips on the catwalk have become another way fashion pays homage to the Spanish surrealist: shown on jackets and dresses at Yves Saint Laurent in 1971, as prints on skirts at Prada in 2000, on shoes in 2012, and again in 2014.

The ultimate surrealist motif, however—thanks to Dalí’s crustacean-enhanced telephone of 1936—is, of course, the lobster. The shellfish has appeared on the catwalk more times than it’s possible to mention. Most beautifully, the Artisanal collection by Margiela in 2014 showed an asymmetrical, beaded chiffon lobster dress that went beyond cartoon reimaginings with its exquisite craftsmanship.