Bobby Kennedy Calling

Amusement business? “What does that mean? Does he have an orchestra, or what?”

By 1959 Bill and Frank were facing new laws to control jukebox licenses as well. Among the measures was a competition-limiting “bumping” rule, which prevented license holders from bumping a competitor’s jukebox from a business without the businessman’s clear approval. The law was obviously aimed at crippling Frank’s strong-arm tactics.

Bill denied his brother was his enforcer and said they’d become successful by throwing solid pitches rather than punches. But those tactics, undercutting their rivals, also came under fire; giving away free music and other perks to customers appeared to break city amusement codes. Bill’s lawyer accused the City Council and cops of “trying to deprive a man of a $50,000 to $100,000 a year business on a technicality.”

Frank’s widening reputation, however, was causing larger problems—problems that were suddenly reaching all the way to the other Washington. The crime boss role he denied in that 1958 lawsuit had come to the attention of the Senate labor racketeering committee, as part of a history-making investigation into the Teamsters union. Bobby Kennedy wanted to chat about it with Frank.

The Seattle Times reported in February 1959 that “Colacurcio, 41, is the only person from the Pacific Northwest summoned ... Robert F. Kennedy, committee counsel, said the hearings will delve into ownership and distribution of music and pinball machines and will disclose racketeering,” much of it swirling around the corrupt activities of the Teamsters, led by Seattle-born union boss Dave Beck, who was suspected of siphoning off Teamster funds for personal use and political payoffs.

The Times story was written by Ed Guthman, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1950 for a series that exonerated University of Washington professor Melvin Rader, wrongly accused of being a Communist. Two years after he wrote about Kennedy’s probe of Colacurcio, Guthman left the Times to work as press secretary for Kennedy, who became attorney general following the election of his brother John F. Kennedy in 1960. (Guthman wrote or coedited four books about Bobby Kennedy, but said his most satisfying career moment was being named to Richard Nixon’s infamous “enemies list.”)

Colacurcio told Guthman that Kennedy was wasting his time—Frank was already out of the music business, he said. He had sold his interests to his brother. “I’m looking for something to do,” he said. “I don’t know why I’ve been subpoenaed. If it is about that music-machine deal last year when I was rousted around, I’m not worried. We never did anything that wasn’t ethical.”

Frank had come to the committee’s attention during the earlier testimony of Portland mobster James Elkins. “Big Jim” was summoned and agreeably testified in 1957 before the committee—officially, the Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, and unofficially, the McClellan Committee, named for its chair, Arkansas Democrat John McClellan. The committee included three future presidential candidates, Bobby and Jack Kennedy and Barry Goldwater, and one ruthless Commie hunter, Joe McCarthy (who would later would fall from grace with the help of Edward R. Murrow, the legendary CBS broadcaster raised in Skagit County). The committee’s main targets were Jimmy Hoffa and his predecessor Beck, the former Broadway High School student and Seattle laundry truck driver who rose through the Teamsters ranks and was elected its president in 1952.

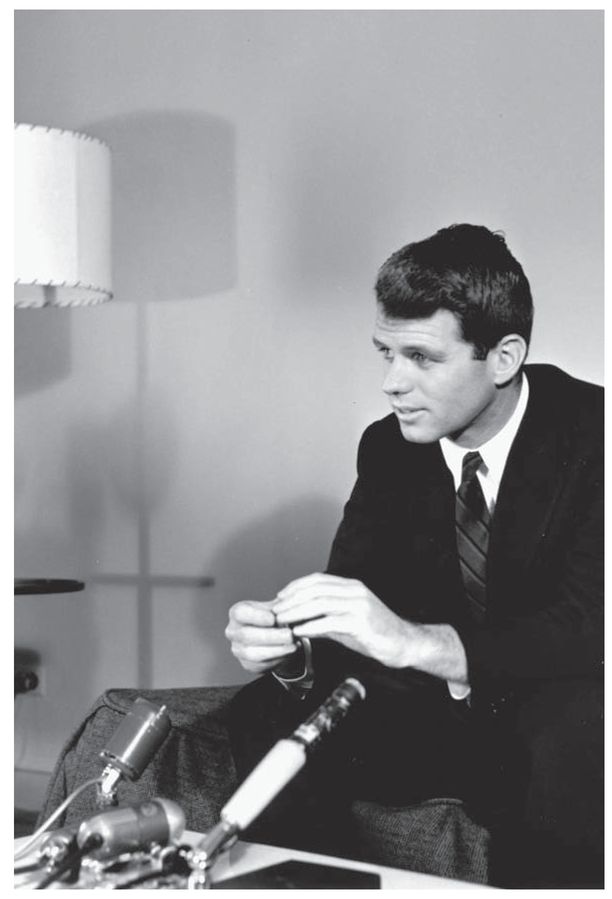

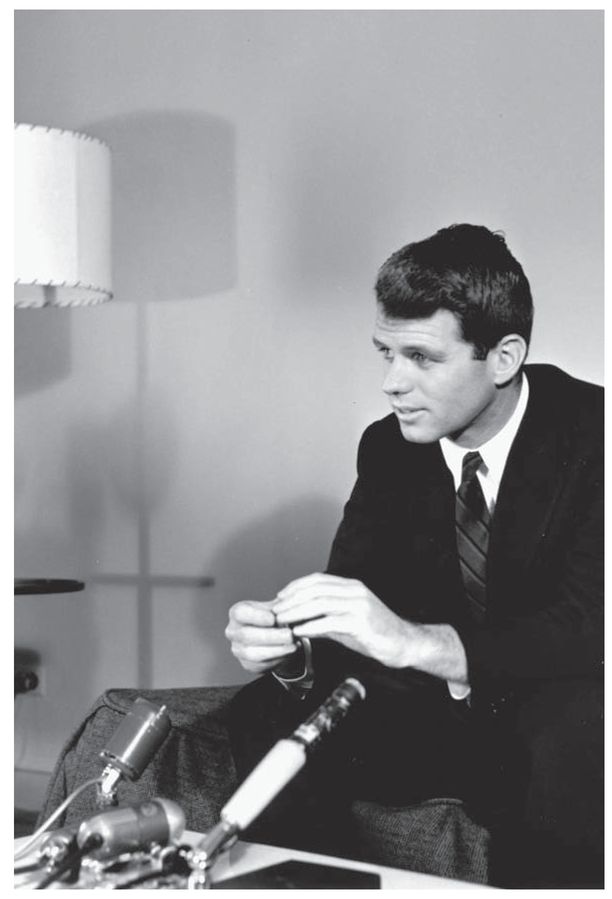

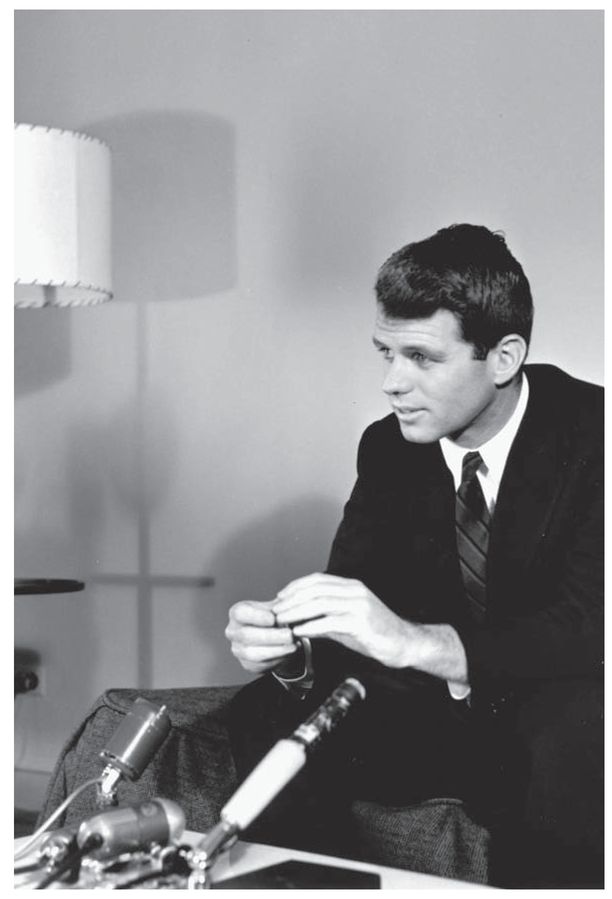

Robert F. Kennedy, then a Washington, D.C., attorney, in Seattle during the U.S. Senate committee hearings on organized crime. Kennedy was the committee’s chief counsel. (Photo: Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, MOHAI)

Beck had been one of the first to appear before the committee, and Bobby Kennedy went at him, wanting to know what happened to $322,000 missing from the union’s treasury. Beck wasn’t saying. He was barely speaking. To 117 questions, he invoked his Fifth Amendment right not to answer.

The hearings, which were spread out over two years, initially focused on reports that Teamsters were trying to take over the rackets in Portland. History seems to have mostly overlooked the committee’s exposure of the Teamsters’ corrosive role in Seattle vice and political corruption, however. While considered a probe of Portland’s rackets, the hearings, in retrospect, revealed as much or more about Seattle’s criminal underbelly and how the union worked in concert with Frank and others to control it. Under Beck, the Seattle Teamsters allied themselves with bars and card rooms, pinball operators and bingo parlors, madams and prostitutes. They could control much of the commerce because they drove the delivery trucks. Businesses that didn’t go along got visits from the archetypical Teamster—size twenty neck, size five hat—who, in addition to making threats, would start fights and cause disturbances. Rather than working for employers, the Teamsters became their bosses.

One of Beck’s vice presidents, Seattle Teamster Frank Brewster, was reported to be leader of the union goon squad that got things done under Beck’s rule. A 1945 General Crime Survey Report, compiled by FBI officials in Seattle, had claimed Brewster controlled a Seattle crime syndicate and used money and muscle to influence Seattle political leaders and vice cops. According to historian Robert C. Donnelly, “Brewster had developed a business and personal relationship with Seattle and Spokane vice racketeer Thomas Maloney, a relationship built on real estate and organized crime. The FBI uncovered evidence that Maloney, an established gambler and prostitute broker and an associate of the Frank Colacurcio crime family, and Joe McLaughlin, a Seattle crime figure and close friend of Brewster, were on Teamsters payrolls. Brewster also reportedly arranged for Maloney to receive a loan from Local 690 to bail out his Spokane restaurant and gambling operation.”

In 1956, Portland’s major newspaper, the Oregonian, first had the story. Under the headline “City, County Control Sought by Gangsters,” investigative reporters Wally Turner and William Lambert detailed the failed Seattle takeover of Portland’s vice industry. It was the start of a series that would go on to win that year’s Pulitzer Prize for local reporting (Lambert went on to work for LIFE magazine, where he disclosed how U.S. Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas had accepted a questionable $20,000 fee, leading to his resignation; Turner joined the New York Times and ended his career as its bureau chief in Seattle in the eighties).

Writes Donnelly: “The Seattle group’s plan to take over Portland’s lucrative vice industry began to unravel. The business relationship among James Elkins, corrupt Teamsters officials, and the Seattle racketeers ended when, according to Elkins, Thomas Maloney suggested opening three or four houses of prostitution and establishing an abortion ring. Maloney arranged a meeting between Elkins and Ann Thompson, a successful Seattle madam.... Soon after, Maloney arranged for a meeting between Elkins and Seattle vice operator Frank Colacurcio.”

As detailed transcripts of the committee hearings show, Elkins told Kennedy the powerful Seattle union bosses were going to move into Portland’s vice trade and needed people who’d been instrumental in Seattle’s corrupt payoff system.

Kennedy: What type of things did they [Teamsters] want to get open?

Elkins: Horse book, punch board, pinballs, houses.

Kennedy: Was there more discussion at that time about houses of prostitution?

Elkins: A little discussion, yes, I think on one or two occasions.

So you talked with the Teamsters, Kennedy said during the 1957 questioning. Did they bring anybody else down from Seattle? “Yes,” said Elkins, “they brought Frank Colacurcio down.”

Who, Kennedy asked, was Frank Colacurcio?

Elkins: Well, I knew him to be another racketeer.

Kennedy: A racketeer?

Elkins: Yes ...

Kennedy: Did you have a meeting with Frank Colacurcio?

Elkins: Yes, sir.

Kennedy: Where did you have a meeting with him?

Elkins: In Tom and Joe’s apartment, Tom Maloney and Joe McLaughlin’s apartment in Portland Towers.

Kennedy: That was Frank Colacurcio?

Elkins: He was a boy that had various things operating in Seattle.

Kennedy: He was in the same kind of business as you, but more.

Elkins: That is right.

Kennedy: And he was operating in Seattle?

Elkins: And Washington, yes.

Kennedy: In the State of Washington?

Elkins: That is right.

Kennedy: What conversations and discussions did you have with Frank Colacurcio when he came down to Portland?

Elkins: He wanted me to arrange so that he could take over three or four houses. I told him if he wanted the houses to go buy them.

Chairman: What kind of houses?

Elkins: Rooming houses for houses of prostitution, sir.

Chairman: All right.

Kennedy: What other conversation did you have with him about them?

Elkins: It wound up in a row.

Kennedy: For what reason?

Elkins: Well, he said he would pay for them out of the earning of them and I said I didn’t think that they would run long enough for that.

Kennedy: Why did you say that?

Elkins: Because I was telling him the truth. I didn’t think they would run; I thought they would get arrested.

Kennedy: So you didn’t reach any agreement with Colacurcio?

Elkins: No, I did not.

Kennedy: He went back.

Elkins: That is correct.

At the time, Elkins was among those snared in a vice crackdown following the Oregonian stories and was under indictment—one of 115 indictments handed down by three different Portland grand juries in 1956 and 1957. To Kennedy and the committee, he was a seemingly candid witness, even if he lied from time to time (he denied he had anything to do with prostitution, for example, but his record shows he had worked as a pimp and married two of his girls).

Elkins said he needed labor’s blessing to place his pinball machines in some Portland locations. He was put in touch with Seattle racetrack and gambling figure Maloney, who was close to Brewster and Portland Teamster leader John Sweeney, who would later become a Seattle Teamster bigwig.

It turned out that, while Elkins wanted Maloney’s help with the union in Portland, Maloney wanted Elkins’s assistance with the cops in Seattle.

Say what? Kennedy asked Elkins.

Elkins: Well, he [Maloney] wanted to open up one gambling and bootleg place in Seattle, in partners with someone. I don’t believe he said who. Maybe it was a colored person. He asked me to speak to an official that I knew of there.

Kennedy: He asked you to speak to the [Seattle] chief of police?

Elkins: That is right.

Kennedy: Did you speak to the chief of police?

Elkins: I did. But I don’t want to give any idea that I ever give him any money, because I haven’t.

Kennedy. But you spoke to the chief of police?

Elkins: That is right.

Kennedy: The chief of police, what did he say about Tom Maloney?

Elkins: He said ... he would see what he could do.

Kennedy: He allowed them to open one place?

Elkins: He either allowed it or arranged for him to open one, yes.

Kennedy: Did you later learn that Tom Maloney turned around and opened two places?

Elkins: I believe that either he or someone else told me that he opened one, and wanted to run the town or something, and he closed that place.

Kennedy: The chief of police to whom you spoke then closed both of the places down?

Elkins: That is right.

Kennedy: With the understanding or feeling that Tom Maloney had overstepped his bounds going into the second place?

Elkins: Yes.

Later, Kennedy asked more about a 1955 Seattle meeting with Maloney and Portland district attorney William Langley.

Kennedy: You came up and met Tom Maloney and William Langley at the Olympic Hotel.

Elkins: Yes.

Kennedy: In a room at the hotel and will you tell the committee what went on in that hotel room?

Elkins: Well, I asked what is the purpose of the meeting and they said it is just a discussion about what we are going to do.... They said they were going to have a discussion about what was going to take place when Langley went in, and I said, “In what way?” “Well,” he said, “you are going to have a little gambling and a little this and a little that.”

Kennedy: What is a little of this and a little of that?

Elkins: Card rooms, horse books, and I think he mentioned three or four houses of prostitution, bootlegging joints, punchboards.

Kennedy: Who said this to you?

Elkins: Bill said, “We are going to discuss what is going to go.”

Kennedy: Bill is Bill Langley?

Elkins: Bill Langley.

Kennedy: He was the newly elected district attorney?

Elkins: Yes, that is correct.

Kennedy: And he was telling you what was to be allowed to go in the city?

Elkins: That is right. He said, “I want Tom in the picture. I am going to cut my take with him until he gets going.”

Kennedy: What did he mean by that?

Elkins: Well, what the payoff was to him, he told me that he had to split it with Tom ...

Kennedy: Now, what did you say when Langley suggested opening three or four houses of prostitution? ... Was that actually suggested by Maloney or was it suggested by Langley?

Elkins: It was suggested by Maloney. ... He said “It is okay with Bill for three or four houses and I am going to take you down and introduce you to Ann Thompson.”

Kennedy: And who was Ann Thompson?

Elkins: Well, according to Tom—I didn’t know her—she was a professional madam.

Kennedy: And what did he say about her?

Elkins: Well, he wanted to introduce me and he said he wanted her to supervise the houses ...

Kennedy: When was the next meeting?

Elkins: In three or four days John Sweeney called me and told me to come to Seattle in the next day or two and so I went up.

Kennedy: John Sweeney is now up in Seattle?

Elkins: John Sweeney is dead.

Kennedy: But I mean he was up at Seattle and Clyde Crosby replaced him in Portland.

Elkins: That is right. So I went to the Teamsters hall in Seattle and Joe McLaughlin meets me in the hall and he takes me into a room and John Sweeney, Tom Maloney, and Joe McLaughlin and another man was in there, who they introduced me to, but I couldn’t swear what his name is right now. Sweeney said “He is one of the boys and you can talk freely in front of him.” They talked about pinballs and punchboards and then he told me “I want you to sit down with Tom” ...

Kennedy: Was there any discussion about how the Teamsters or the Teamster union would help?

Elkins: That is correct. They said with the power of the Teamsters, and their weight behind it—Portland was not an open town and that the chief of police wouldn’t go along with an open town—and they said either he will go along or the Teamsters will get him moved, meaning the chief of police.

Kennedy: They were going to get the chief of police moved?

Elkins: If he didn’t go along. But they thought I was lying to them even at that time and they thought that I was operating under protection.

Kennedy: But they told you that they would have the help and assistance of the Teamster officials in Portland?

Elkins: That is correct.

Kennedy: And that [Seattle Teamsters] Frank Brewster and John Sweeney were behind this operation?

Elkins: That is right.

Later on, Kennedy asked Elkins about the role of Seattle madam Ann Thompson, whom Elkins went to see after she checked into a Portland hotel.

Kennedy: And what was discussed at that time?

Elkins: The minute I walked in the room she said “Just take it easy. I am not trying to get you to change your mind. I don’t want to operate. But I want you to tell Maloney and his people that I was here and talked to you, but we couldn’t get together,” I believe is what she said, as near as I can remember. That might not be word for word, but that was the gist of it. She again repeated that she couldn’t operate one or two or three places on the small percentage she would get. If she had a whole hatful of places, she probably could make a dollar.

Kennedy: So she wasn’t very interested in it?

Elkins: She was not....

Kennedy: You have not seen her since that time?

Elkins: No, I have not.

As Elkins stepped from the stand, Ann Thompson dramatically stood up in the hearing room. Tall and saucy, she was nonetheless shy, and held her big black purse to her face, saying, “No picture.” As she walked to the stand, Kennedy announced, “The witness does not want her picture taken.” Chairman McClellan beckoned to her. “Have a seat. You may be sworn first,” he said, and then he addressed the cameramen in the photo gallery: “The photographers will not take any pictures until the chair gives you permission to do so.”

Thompson, “dressed to the nines,” as press reports put it back then, was sworn in but had little to tell the committee, essentially confirming Elkins’s story. She was doing a good business bedding the men of Seattle and Tacoma, she indicated, while Portland looked like a money loser, even with the Teamsters along for the ride. Maloney had put her in touch with Elkins, so she felt they should at least talk.

Kennedy: Does it seem strange to you that if Mr. Maloney fixed an appointment up with Elkins, on the assumption that Elkins wanted you to come down, that when you had your first conversation with him he discouraged you?

Thompson: I will tell you, at the time I guess I was too much of an eager beaver ...

Kennedy: You had a pretty good reputation in the state of Washington for running these homes.

Thompson: Thank you.

At a later senate hearing, in March 1957, Brewster, the Seattle Teamster, showed up to defend his union and himself, but gave up a lot of ground in the process. He confirmed his relationship with one of the Colacurcio brothers’ pinball rivals, Fred Galeno.

Kennedy: Who is Fred Galeno?

Brewster: Fred Galeno is a person that is in Seattle, Washington.

Kennedy: What do you mean, a person in Seattle, Washington?

Brewster: Well ... who is he—he is a person.

Kennedy: Is he in business in Seattle?

Brewster: Yes, he has a business.

Kennedy: What is his business?

Brewster: It is an amusement business.

Kennedy: What does that mean? Does he have an orchestra, or what? ...

Brewster: He is in the amusement business that includes jukeboxes and pinballs.

Kennedy: He is in the pinball business?

Brewster: Yes. He is one of the oldest—one of the members of the oldest families in the city of Seattle.

The Teamster boss told how the union spent a lot of cash they didn’t keep records on, almost impulsively doling it out to political candidates. Kennedy asked Brewster about one $4,000 allotment.

Kennedy: How was that to be spent, that $4,000?

Brewster: To be spent on candidates. [Teamster official] C. O’Reilly was in full charge, authorized by the executive board.

Kennedy: Is there anything in your books to indicate to whom that money went?

Brewster: No, there isn’t. ...

Kennedy: What would prevent Frank Brewster taking the $4,000 and using it to purchase or pay for some of his personal bills?

Brewster: That never was the purpose....

Well, Kennedy wanted to know, where was this fund, this “special fund” for politics, located? The committee had traced much of the money from Local 174, which had been headed by Brewster. Supposedly earmarked for political campaigns, the total came to precisely $99,999.65 for just the 1952 elections. Where, exactly, had that money been kept, and to whom did it flow? Brewster couldn’t say. The admission seemed to surprise Chairman McClellan, who stepped in with his own questions, as did senator Karl Mundt of South Dakota.

McClellan: This sounds like a lot of money for working people. Do you mean you cannot give any accounting of this money, where it went?

Brewster: That was handled by Claude O’Reilly.

McClellan: I know, but you were secretary and treasurer. You are supposed to know where it goes. Do you mean to say you did not know?

Brewster: I did not know.

Kennedy: I might say, Claude O’Reilly is dead now, is that right?

Brewster: Yes, he is dead now.

Mundt: Is it your position, Mr. Brewster, that all $99,000 of this was spent for political purposes in Seattle?

Brewster: And the state of Washington.

Mundt: $99,000, that is just in one campaign year, I presume, 1951 to 1953. You spent $99,000 in the state of Washington for political purposes in the campaign of 1952?

Brewster: It sounds like a big figure, but spread over everyone that knocks on your door, it isn’t too much.

Mundt: Do you support everybody who knocks at your door?

Brewster: Most everyone. We ride a couple of horses in the race once in awhile.

Kennedy later steered the questioning toward the Seattle-Portland vice connection, and Brewster was quick to defend his old buddy and Teamster leader Sweeney: he had been maligned by the hearings, where “any hoodlum,” Brewster said, “who chooses can get up and say ‘John J. Sweeney did this,’ and ‘John J. Sweeney did that,’ without fear of successful contradiction.”

Well, what about you, then? Kennedy said, regarding “that talk or discussion you had with Jim Elkins in your office. ... Did you say anything to him about the fact that he would be wading across Lake Washington in concrete boots, or anything like that?”

“I never said that to him or anyone in my life,” Brewster said.

Kennedy then asked about the shadowy Maloney, the Portland-Seattle go-between. Brewster said there was nothing to it. The Teamsters had loaned him money to start up a Seattle card room, which Brewster didn’t consider to be gambling. “They play a certain kind of cards,” he said. “I don’t think they play poker.” (They did.)

He also didn’t know that Maloney—for whom Brewster got a job at a racetrack—was a bookie. Actually, Brewster said, though he’d known Maloney two decades, he didn’t know him that well. Kennedy should really be asking Sweeney, another dead guy, about that.

Kennedy: You see the difficult position that it puts the committee in. [Maloney] had this history of twenty years of friendship with you, and you signed the checks to pay his bills down in Portland, you and John J. Sweeney ... and then you come before the committee and say that it is all John J. Sweeney’s responsibility, that it is his fault. And John J. Sweeney is dead so we cannot ask him about it. You see that that is a little difficult to understand.

Brewster: Well, it might be for you, but it is not for me.

The televised hearings were watched by 1.2 million American households as the panel probed Teamsters’ misuse of union funds and its ties to labor racketeers and organized crime. Only a handful of the more than one hundred people indicted in the Portland scandal were ever convicted, though they did include District Attorney Langley, who got off with a $428 fine for refusing to prosecute gamblers. Elkins was also convicted—of illegal wiretapping, having secretly recorded some of his conversations with the Teamsters. But the conviction was later overturned.

More than twenty Teamsters were convicted in subsequent criminal cases, including Jimmy Hoffa, found guilty of jury tampering in connection with an attempt to bribe a McClellan Committee investigator. After a long appeal, he went to prison for four years, was eventually pardoned by Richard Nixon, and quit the union. He was last seen in 1975 being driven away from Machus Red Fox restaurant in suburban Detroit, where he was planning to meet two Mafia leaders. Most versions of his final departure place him inside an oil drum, in which he was possibly cremated and/or buried within the fresh concrete of New Jersey’s since demolished Giants Stadium. But he has also been reported to be, wholly or in part, in the Florida Everglades, a New Jersey Sanitation shredder or landfill, and an assortment of freshly laid East Coast freeways, buildings, and bridges.

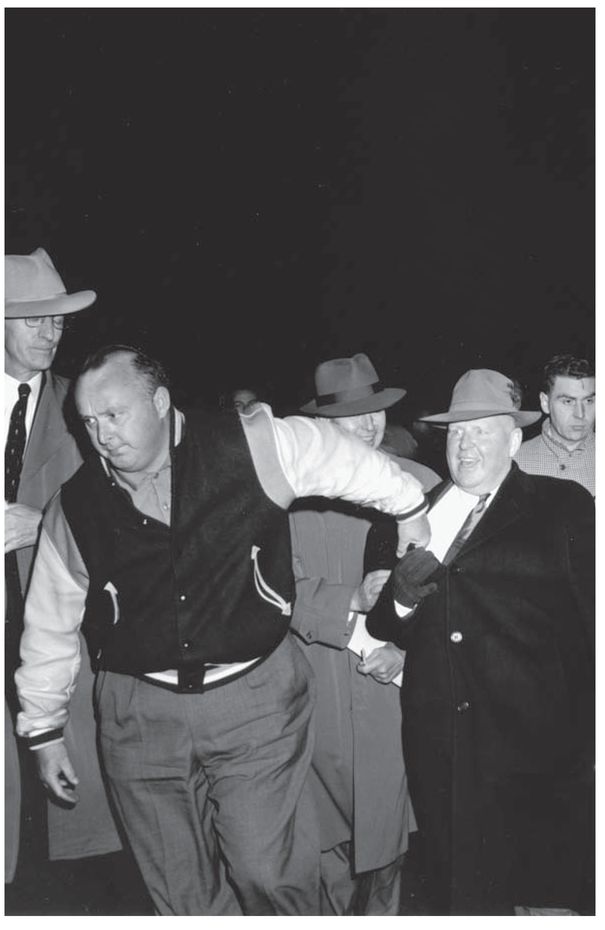

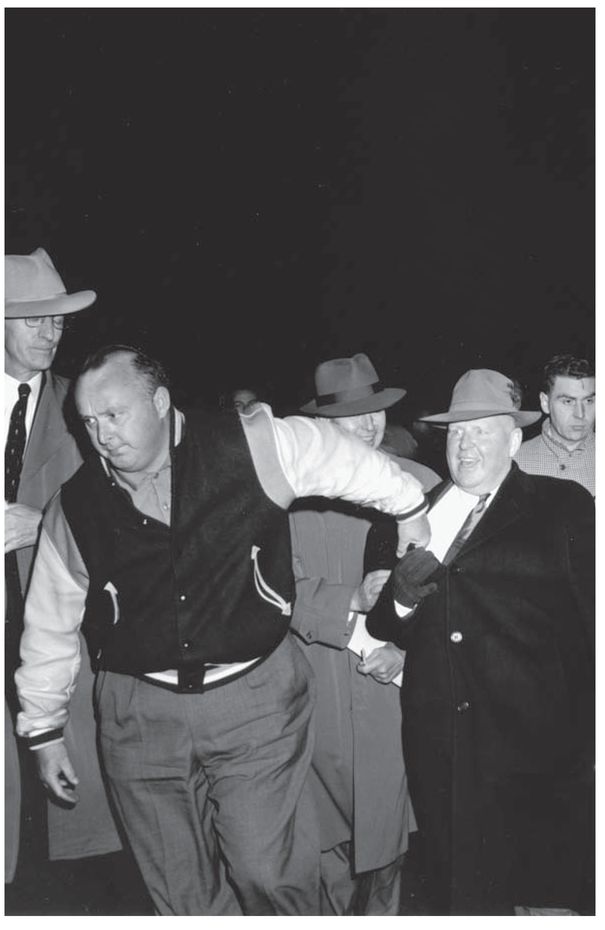

Dave Beck, a leader of the Teamsters on the West Coast, being pulled away from reporters by his son, March 1957. (Photo: Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, MOHAI)

Under pressure, Dave Beck opted not to run again for Teamsters president. In 1959 he was convicted of Washington state corruption charges for pocketing $1,900 he’d gotten from the sale of his union-owned Cadillac and separately was found guilty of six counts of federal income tax evasion. A federal sentencing judge, George Boldt, said as Beck stood before him: “No bootblack or newsboy of Horatio Alger’s imagination ever rose from a more humble beginning to a greater height than Dave Beck.” But “the exposure of Mr. Beck’s insatiable greed, resulting in this fall from high place, is a sad and shocking story that cannot be contemplated by anyone with the slightest pleasure or satisfaction.”

Beck went to prison for three years in 1962, but he turned out to be not quite the defeated man described by Boldt. Once free, he lived off his $50,000 Teamsters pension, invested in parking lots, and became a multimillionaire. He died in 1993, at age ninety-nine.

He went to his grave absolved of the grand larceny conviction for selling the Caddy. It was wiped away in 1965 with a pardon from Frank Colacurcio’s former attorney, Governor Al Rosellini.