Tolerance on Trial

A cop told him that bar work can be dangerous, and “I’m sure you don’t want anything to happen to your little girl.”

By the seventies, Seattle was destined to host dueling grand juries—one federal, one state, both looking into the surfacing story of Seattle vice. Frank was indicted by a federal grand jury for racketeering, along with bingo parlor operators Charlie Berger and Harry Hoffman. Hoffman was accused of making political payoffs, and Berger was accused of paying Colacurcio $3,000 a month per bingo location; in return, Frank would “guarantee” that cops would maintain a tolerance policy and overlook gambling violations at the two men’s parlors. U.S. Attorney Stan Pitkin also claimed the three conspired to bring illegal gaming equipment across state lines—more than one hundred thousand bingo cards imported from Colorado.

“I have never had any payoff connections with police,” a bespectacled and balding Colacurcio, fifty-one, said of his first federal indictment. “On the contrary, the police have been trying to nail me to the wall.... The next thing, they’ll say I took a lollipop from a kid.” Besides, Frank added, the tolerance policy was approved by City Hall. “Why would police have to be paid to maintain it? It’s ridiculous.”

Charged in a separate and bigger headline-making case was former assistant chief of police Milford E. “Buzz” Cook, who’d been a top assistant to now-retired chief Frank Ramon. Cook, who also briefly became police chief only to be indicted for perjury, denied knowledge of the police payoff system that he helped facilitate. During his 1970 trial, officer after officer took to the witness stand and testified about payoffs, giving some of the first public details on how the money moved through a system that dated back a quarter century and involved at least seventy officers. Cash flowed from club owners who were pressured to make payments or did so in order to operate illegally and maintain their monopoly, with the booty going to cops and to industry middlemen who pushed it up the line, doling out kickbacks of money, liquor, and other favors. Some cops were getting up to a $1,000 a month. Testimony was explicit, but much of it was unverified. One assistant chief, George Fuller, said he had “heard” that considerable cash had gone to City Council member Charles M. Carroll (known as “Streetcar Charlie” because of his former job with the old Seattle Transit System and no relation to prosecutor Charles O. Carroll). Pinball machines were licensed under a committee overseen by Streetcar, and he was already receiving thousands in campaign cash from the amusement industry.

Fuller said Streetcar, as a Council member, was reputedly getting $300 a month from a vice officer whose squad was sharing as much as $6,000 a month in payoffs. Vice cops kept payment records on index cards, with payees assigned code names. Those who didn’t pay at the first of the month would be faced with drop-ins by beat cops who harassed customers, checking IDs and turning up outstanding tickets or warrants. The uniforms kept half what they were paid. The other half went to their sergeants, who kept half of that, and passed the remainder upward. Those at the top were getting money though different branches of the pipeline, leading to big monthly payoffs.

Among those testifying was Jake Heimbigner, owner of the Caper Club, a gay nightclub in the Morrison Hotel across from police headquarters, then on Third Avenue. He paid $165 in weekly protection money to stay open, he said. A police sergeant would call him and arrange meetings at various neighborhood locations where the payoffs would be made.

Beverly Grove, manager of Russell’s Casbah Tavern and Cardroom on East Madison Street, said she paid $125 a month to the cops, then one day decided she’d had enough. Suddenly there was a lot of police work to do at the Casbah. Cops began ticketing customers for traffic violations and jaywalking, she said. “There isn’t a customer in my tavern that hasn’t been harassed,” she testified. Her father, the tavern’s owner, said a cop told him that bar work can be dangerous, and “I’m sure you don’t want anything to happen to your little girl.” Unable to make money, the Casbah closed.

Cook was convicted and went to prison in a tumultuous time for the SPD. Besides the corruption, the SPD was dealing with antiwar protests and bombings around Seattle. Rioting was an almost daily event in the early seventies, and demonstrators also took over Interstate 5. New mayor Wes Uhlman told a U.S. Senate committee there had been ninety explosive and incendiary devices set off from February 1969 to July 1970, damaging businesses, schools, churches, and private homes. Seattle ranked behind only New York and Chicago in the number of protest bombings and, per capita, ranked first. Police officers regularly worked twelve-hour shifts and routinely patrolled the streets six to a car, dressed in full riot gear. It was a war about war, with cops responding to demonstrator violence with beatings. In one University of Washington event, cops even covered up their names and badge numbers so they couldn’t be identified in the assaults. More than three hundred brutality and misconduct complaints were filed in 1969 alone. Cops went from being called bulls; now they were pigs. SPD officers in return adopted a pig as a mascot and coined the motto “Pride, Integrity, Guts”: PIGs.

Mayor Uhlman had just appointed an assistant chief, the respected Frank Moore, as top cop, when Moore too became tainted by the scandal, invoking his Fifth Amendment right before the U.S. grand jury. Moore then stepped down “due to his health.” Uhlman began to bring in a series of outsiders, all California cops, to serve as interim chiefs. (Seattle would run through six police chiefs from 1969 to 1970: Ramon, followed briefly by Cook; then Moore, followed by Charles Gain, out of Oakland; Ed Toothman, also brought in from Oakland; and George Tielsch, from Garden Grove, California). The department discovered that as many as forty officers were involved in the payoffs, which appeared to have for the most part ended in 1968. Most of those named had already left the force. SPD officials asked prosecutor Charles O. Carroll to press felony charges against four officers who shook down businesses that catered to gays and lesbians, but he opted for misdemeanor charges and sought only suspended sentences.

Seattle attorney Christopher Bayley saw that as something of a cover-up and signed up to oppose Carroll for the prosecutor’s job in 1970. A county grand jury could get at some of the illegal low-hanging fruit of the payoffs that a federal grand jury couldn’t, he said. Bayley easily won the election, kicking out the embattled Carroll, a onetime University of Washington football star, after a twenty-two-year reign. As one of his first duties, Bayley formed a grand jury that in 1971 indicted both Charles Carrolls—prosecutor Chuck and Council member Streetcar Charlie—along with seventeen others, including ex-chief Ramon, his former assistant Buzz Cook, and former county sheriff Jack Porter, for “conspiracy against government entities.” Eventually, a hundred cops, many retired, were implicated in crimes that dated back thirty-five years.

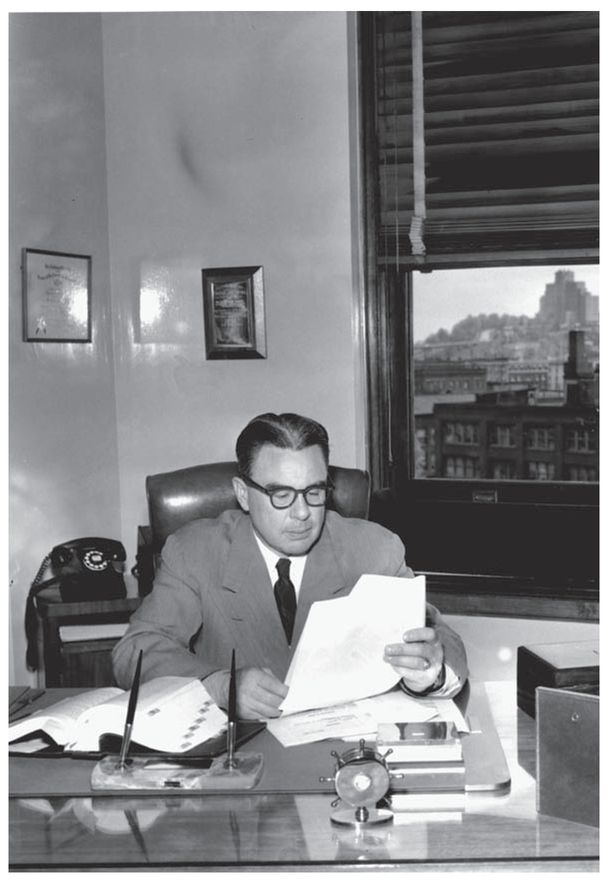

Charles O. Carroll, former Husky football star, was the King County prosecutor for twenty-two years. His record of public services was tarnished when he was linked with Seattle police bribery connected to gambling and other vice activities. (Photo: Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, MOHAI)

Prosecutor Carroll’s conspiracy role, the grand jury alleged, included being present at a meeting with pinball czar Ben Cichy and Sheriff Porter to figure out how to extend a tolerance policy countywide. It was a low point for Carroll, an All-American running back in 1927-28 and a 1964 National Football Foundation College Hall of Fame inductee. Most legendary was his 1928 college performance in a game against Stanford. Even though the Huskies lost 12-0, Carroll dazzled the crowd with such slash and dash that the Stanford players carried him off the field. President-elect and Stanford alumnus Herbert Hoover was so wowed, he exclaimed, “That man is the captain of my All-America team!”

Bayley later said he considered fellow Republican Carroll—whose county car was equipped with red lights in the grill so the prosecutor could dramatically speed to crime scenes—the closest thing to a local political boss. Carroll had dirt on almost everyone and used it to bend arms, Bayley said, adding, “He was called ‘Chuck’ by everyone, and ‘Fair Catch’ by critics who believed he never filed tough cases.” Carroll had also been the first prosecutor to introduce the televised confession. Now and then he would show up on TV, sitting at a table with the suspect sandwiched between him and a deputy prosecutor. The perspiring suspect would explain how he did the awful crime, as Carroll nodded affirmatively for the cameras. Carroll not only scored campaign points, the dog and pony show was much cheaper than an actual trial.

Bayley also recalled how he visited Carroll “as a courtesy” to let the longtime incumbent know that he would oppose him in the 1970 primary. “He sat at the head of a long, polished conference table, flanked by his finance chairman and the Republican county chairman, all equally incredulous that he could be challenged by a thirty-two-year-old lawyer who had never tried a criminal case,” Bayley said.

But once he dethroned Carroll and handed down the indictments, Bayley was on a downhill course. He was forced to drop some cases, including Streetcar’s, while others were dismissed. By the time of trial in 1973, plea agreements and pretrial rulings trimmed the defendant list to ten. Ex-chief Ramon, who was alleged to have received liquor from operators of gambling establishments, got the charges against him dismissed before trial, after it was determined he’d testified before a grand jury under a grant of immunity.

Then King County Judge James Mifflin dismissed most of the remaining cases, including Carroll’s. The evidence against the former prosecutor was particularly troublesome, the judge said. Carroll’s accuser had admitted to some earlier legal run-ins and court appearances wherein he often lied under oath.

In April of 1974, the final defendant, a former cop, pleaded guilty to accepting bribes and was sentenced to two months in jail.

Chuck Carroll would later claim he never approved of the tolerance policy. “I said bring me the facts for a case and I’ll file it. I always worried that there might be payoffs to permit the stakes to go higher and higher. And that’s what happened. The names of some good people were dragged through the mud,” including, he inferred, his. When Carroll died in 2003, prosecutor Norm Maleng, the man who succeeded Bayley, said, “He was really a giant of his era, both in the sports and legal arenas. He was a grand old man, and I miss him. I really do.”

The city’s biggest corruption scandal had ended with a whimper, though Bayley felt it had changed the city. In a January 2007 op-ed piece he wrote for the Seattle Times on the fortieth anniversary of that paper’s opening series on the shakedown system, Bayley said the indictments were at least a learning experience for the city.

“To this day I don’t know how much Carroll knew about the payoff system. But he did not understand the degree to which press coverage of the tolerance policy had undermined his support from King County voters,” he wrote. “Seattle finally began to understand how its legal and political system had been corrupted by years of payoffs ... the grand jury and criminal trials exposed and effectively dismantled the system. Since then, Seattle police and local officials have had their share of controversy, but there has never been an allegation of [widespread] corruption. We forget those events at our peril. The recurring lesson is that government attempts to regulate human activity—be it drinking, gambling, drugs or whatever—must be based on public consensus and carried out transparently and openly. If there is no consensus, as with after-hours drinking in the ’50s and ’60s, there is an enormous temptation for police and public officials to ‘wink’ at violations, and the winking can easily devolve into corruption.”

A few years back, Gordy Brock, one of the bar owners victimized by the police payoffs in that era, said in an interview, “The beat cops were bagmen, and I mean that literally. Every week, I put a paper bag on the bar. The beat guy comes in, sits down, has coffee, picks up the bag [with $100 cash] and says goodbye. In return, I don’t get busted for code or liquor violations.”

In 1949, at age twenty-one, Brock opened the Fremont Tavern (later the Red Door) and ran a number of places, including a rough bar on Capitol Hill where the lights occasionally failed. “When they came back on, everyone would be pointing a gun at everyone else,” he said.

But it was the cops who really worried him during half a century in the business, winding up as owner, with wife Sandee, of the Pike Place Bar & Grill at the market. Until his 2001 death, at seventy-two, he was among the last of the old-time tavern keepers and payoff victims still in the business.

His cop bagman was never indicted, Brock said. In fact, he got full city retirement and hung around Bock’s market bar for years afterward, working as a security officer and mooching drinks. It was some solace that post-tolerance mayor Wes Uhlman showed up to cut the ribbon at Brock’s renovated Pike Place Market grill years later. “Still,” Gordy said of the mayor, “I wanted to ask him for my money back.”

Meanwhile, in the seventies, the feds were asking Frank Colacurcio to pay up. Which he did.