Going Hollywood

“The guy’s wiggling and screaming and saying, ‘Don’t drop me, I got the money, I’ll give it back!‘”

By 1978 Frank Colacurcio had returned to his Seattle bar empire with the enthusiasm of most former inmates: where are the ladies?! He steadily expanded his topless empire with new venues and by the start of the eighties ran a handful of Seattle and King County clubs and another half dozen scattered from the Southwest to Alaska. At the moment, he was doing better than his brothers at staying out of jail. Bill Colacurcio had gone off to run a family-connected club in New Orleans, where he was convicted of illegal gambling and racketeering, having bribed undercover officers who posed as corrupt cops. Brother Sam was running topless bars in Arizona and in the family tradition also found his way to the federal pen, convicted of skimming profits. He got four years by plea-bargaining charges of conspiracy to commit bribery, theft, and trafficking in stolen property at two clubs in Phoenix and one in Tucson. Two other brothers, Patrick and Daniel, also pleaded guilty to criminal charges connected to the Phoenix and Tucson topless operations and did prison stints.

Not that anyone had forgotten Frank. A 1979 report compiled by the state patrol’s Organized Crime Unit contended that Frank controlled a “criminal organization” operating topless taverns and other businesses in the state, and looked like a good collar for any jurisdiction with a well-funded vice squad. At a later legislative hearing on crime in New Mexico, a federal investigator testified that Frank’s gang numbered about fifty throughout the West. Through his exploits, Frank was providing full-time employment for task forces—and for writers, as well, including William Chambliss. A sociologist and author, he wrote a popular 1978 book,

On the Take, that delved into Seattle’s organized crime and tolerance policies. It was a generally accurate inside account, but some questioned its precision. He refers to the Blethen family’s

Seattle Times, for example, as a Hearst newspaper, and his account of young Frank Colacurcio’s rape conviction—at odds with the court record—portrays Frank’s plea as “taking a fall” in return for a political deal arranged by his unnamed attorney (Al Rosellini):

Frank was the son of a vegetable farmer in the county. His family was comfortable but neither notorious nor wealthy. He and some of his young friends were untouched by crime or rackets to any significant degree, but they were touched by the sin of many American men—womanizing. One of the women that Frank slept with regularly was only sixteen years old. She was also sleeping with several of Frank’s friends. The young woman was arrested, and she confessed to the police that the older men had been having sex with her for some time. The police threatened all four of them with jail sentences. The four men denied the charge, and the police had only the uncorroborated testimony of the girl.

A young lawyer who was active in politics managed the business affairs of Frank’s family. The four accused rapists fell to arguing among themselves as to how to get out of the predicament. They called in the family’s lawyer to mediate. The lawyer contacted the police, who told him that someone had to stand trial. The police agreed, however, to drop charges on all but one of the defendants in return for a guilty plea. The lawyer took out a checklist and added up the pros and cons of having one of the four plead guilty to the charge. Some were married, some had businesses that would suffer; Frank was single and could afford the stigma. He was also only twenty-three, so the effect of having sex with a sixteen-year-old would look less awesome. The lawyer promised there would be no jail sentence, only probation or a suspended sentence. He also promised that when it was over the other men would put up the money to set Frank up in business.

The lawyer’s power to negotiate a deal was less than he indicated it would be. He did get the charges dropped on everyone but Frank, but Frank had to spend eighteen months in the state reformatory. On release, however, the lawyer kept his promise and set Frank up with a liquor license, a tavern, and a going business, without Frank’s having to invest any money.

Accurate or not, it contributed to Frank’s legend as a mobster, and a ballsy one at that. On one occasion, Chambliss writes, “a leading politician called Frank in to put him in his place. According to someone who witnessed the encounter, when Frank entered the room, the politician said, ‘I understand you are the biggest pimp in the state.’ Frank replied, ‘Yeah, and I hear you like to play with little boys.’”

That quote, though it may sound contrived, may more likely be true. One of Seattle’s oldest vice rumors is that of high-ranking politicians having once been involved in a boy-sex ring. Reporters from the fifties into the nineties heard cops and others speak of it; the usual suspects included state and national politicos. Giving credence to such talk was the 1988 suicide of King County Superior Court Judge Gary Little, who took his life after learning that a story on allegations that he had abused children would be published in the next day’s

P-I. There had long been questions about Judge Little taking juvenile offenders to his home, while others claimed they were abused by him. In the

P-I story, reporter Duff Wilson, now with the

New York Times, revealed Little had been disciplined for inappropriate contacts with juvenile offenders by the state Commission on Judicial Conduct, but details had been kept secret. As the paper went to press, a courthouse janitor discovered Little’s body in his chambers next to a gun and a suicide note:

I have chosen to take my life. It’s an appropriate end to the present situation. I had hoped that my decision to withdraw from the election and leave public life would have closed the matter. Apparently these steps are not satisfactory to those who feel more is required, so be it. I will say one final time that I am proud of my efforts and accomplishments as a Superior Court Judge. I am deeply appreciative of those who have wished me well these past few weeks.

In an interview over late-night drinks a few years later, a Seattle police detective and former ranking vice squad officer revealed he had “the file” on this rumored history of man-boy rapes by our elected leaders. “Names, dates, everything,” said the detective, who’d been an extremely reliable source for earlier stories. He was willing to reveal the file, which—according to him—included undisclosed police investigations. The next day, his response was, “What file?” He couldn’t seem to find it anywhere. Maybe in the end it was the ravings of a drunk. He had said he’d begun compiling the file because he might need it for “leverage” one day. As it turned out, the detective was later tried on theft charges and forced out of the department. If he had such a file, it didn’t appear to have helped him in the job extortion market.

The mob lore about Frank naturally evolved into Mafia comparisons. Friends say he also seemed to fancy the role of Hollywoodesque gangster from time to time. Take the night in San Francisco when he hung a man out a window, as the story goes.

“I don’t remember his name,” says a longtime Frank friend and business associate, “but the guy had made off with funds from the state Democratic Party. This was a big disappointment to the head of the party, who was Frank’s old friend.

“So Frank goes to work and tracks the guy down in San Francisco. He finds him in a hotel room and, five stories up, opens the window and holds the guy out over the street by his neck. The guy’s wiggling and screaming and saying, ‘Don’t drop me, I got the money, I’ll give it back!’ Which he did.”

The incident amused Frank, says the friend, who understood how it grew his reputation. And it wasn’t an isolated moment, says the friend, recalling another of Frank’s tough-guy antics.

“One day we’re sitting in the lobby of the Lake Quinault Lodge, by a big fireplace, talking business,” he says, referring to the historic lakeside lodge on the Olympic Peninsula where Frank regularly went on wintertime fishing trips. “This was Frank’s favorite place. He liked the setting, the quiet.

“So we’re talking, and this woman comes up and starts looking at the coffee table between us. It’s one of those wood-burl tables, for sale for $600. She sits down and rubs it and pokes around and starts asking about it. We don’t know anything, we tell her.

“She sits there rubbing and poking, and Frank can’t say what he wants to say [to the friend]. She won’t leave. So finally he stands up, goes over to the hotelman, peels off six $100 bills, walks back, picks up the coffee table, and throws it in the fucking fireplace! The woman was running before her feet hit the ground.”

The Mafia-accusation stories were a sort of running joke among Frank’s friends. One of the reliable tales was the day Frank was waiting in court, when a cell phone, belonging to an investigator on his defense team, rang. The ring tone was the theme from The Godfather. A friend insists another Godfather-inspired event is true as well—that Frank ordered a bloody horse’s head be left in the bed of a prosecutor in the seventies. It could never be substantiated, and those who might know said they hadn’t heard the tale even as a rumor. “No, it happened, they broke in and put the head in the guy’s bed,” the friend says emphatically. “The prosecutor never said anything about it publicly that I know of.”

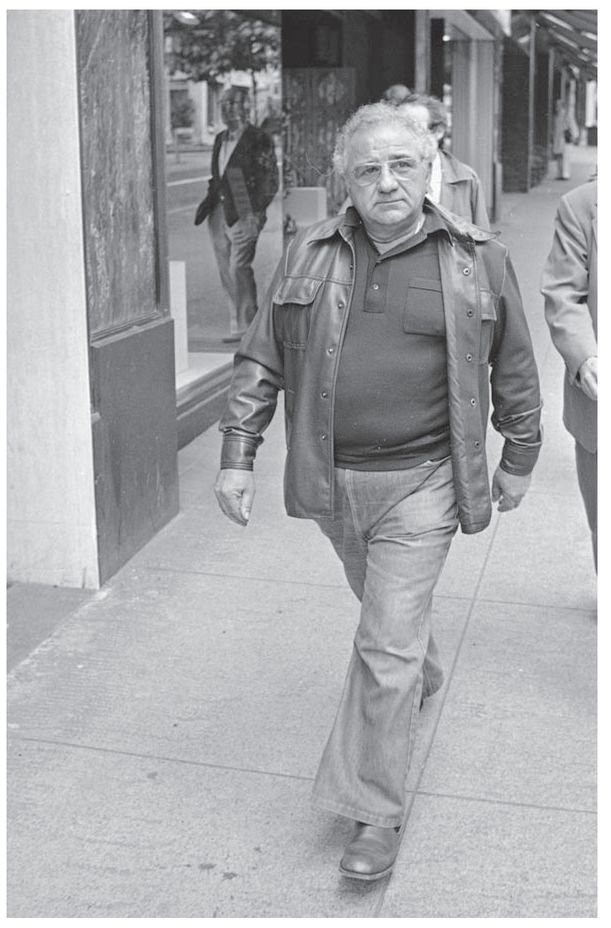

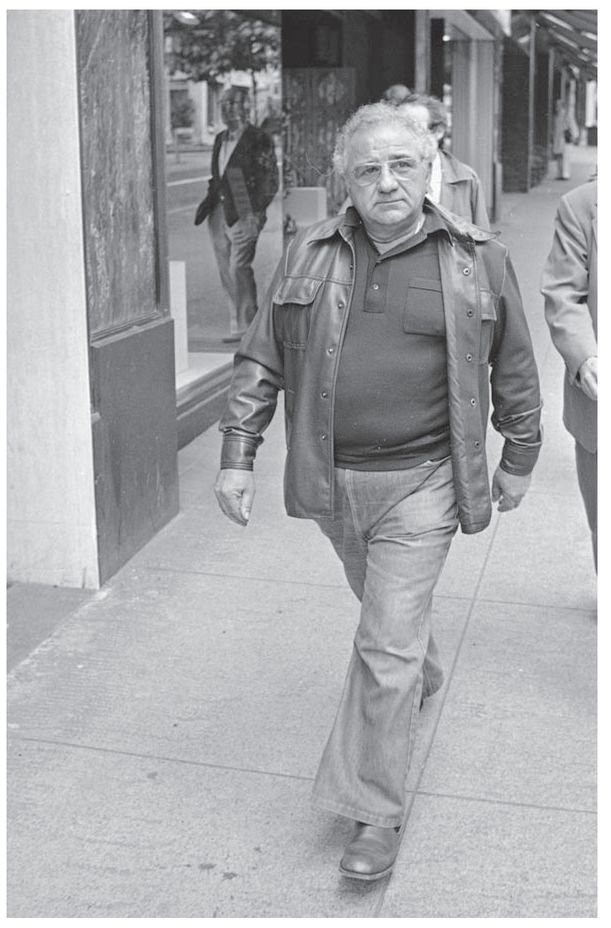

Frank Colacurcio walks through downtown Seattle July 9, 1980, after facing arraignment at the federal courthouse on charges of conspiracy to evade income taxes. (Photo: AP/Wide World Photos/Gary Stewart)

Frank is not Mafia, no way, the friend adds. “He has his own crime family. Literally.”

Never much of a sinner in the smoking and drinking categories, Frank in his earlier days was typically polite in meetings with reporters or when turning down an interview that might convict him of something. “I don’t want to be rude,” he told one reporter, “but I have learned over the years to watch what I say to reporters and I would really rather not comment right now. I hope you understand.”

In one eighties chat with a writer, over the pulsing music at the Firelite on Second Avenue, Frank was putting in a shift as bartender. He was a stocky rock of a man then, at 180 pounds, married for a quarter century to an understanding but distant wife. When he wasn’t angling for money and women, he liked to fish in Alaska. He flashed a well-practiced angelic smile and sometimes kidded with strangers—at one of his federal tax trials, he stopped an IRS agent in the court hallway and asked if his new wool suit would be a deductible legal expense.

Frank talked animatedly if the subject interested him, and it did this night.

“That dancer over there,” he said, pointing to a topless woman writhing under amber-colored lights on a mirrored Firelite stage, “that’s a guy. Was a guy. Or is a guy, I don’t know. Can’t remember if he got the operation or is gonna get it. Look at the money they’re throwing at him. He is one good-lookin’ broad!”

A longtime Colacurcio associate recalls there were three preoperative transsexuals or transvestites who danced as women at Frank’s clubs. One became the object of affection of a local politician who was friendly with Frank. One night at the club, Frank and the associate spotted the politician (the associate wouldn’t name him) sitting in a booth with the busty preop—the pol’s face was smeared with lipstick. Frank was breaking up with laughter when the unknowing politico raced up to the bar and ordered more drinks for “me and my girl.”

Says the associate today: “I told Frank to let me buy this round. Frank said no way! He had to have the honor. We never did tell the guy he was smooching another guy.”

That night behind the bar, Frank repeated his mantra about being unfairly maligned as a “mobster.” He was a businessman, in a business that attracts trouble and troublemakers, he said. That’s all.

Thing is, as several of his associates point out, he was never satisfied with legally pocketing easy money. It was in his blood to find some way to cook the books and go to prison even when he knew the feds were watching. So nobody was surprised when, in 1981, only a few years out of prison, he got snared once more for skimming at two of his dance joints.

Then sixty-three, Frank and partner Kent Chrisman, forty, were charged with evading corporate income taxes at the Bavarian Gardens topless tavern in Bellevue and the Brass Tiger in Federal Way, among his first forays into the burbs. It was a near repeat of his 1974 case and, “Well, you know it is tough to beat a charge like that,” a kind of hapless-sounding Frank allowed.

At his federal trial in Portland—his reputation almost guaranteed a conviction in Seattle, his attorneys said—prosecutors began dredging up the past that Frank said was all lies. They spoke in the superlative—kingpin, legend, empire—and told a jury how lackeys ran his operations because, as he admitted at his last trial, he couldn’t get liquor licenses in his name. This time, partner Chrisman was the front man, said U.S. prosecutor Ronald Sim, and the twosome’s accounting systems were “almost audit proof,” the key word being “almost.”

Frank’s attorney portrayed him as the victim of government harassment, and codefendant Chrisman insisted he was the owner; after all, he was the guy who gave away free beer to everyone, including any member of the Seattle Seahawks, who showed up regularly. Frank, he said, was merely a consultant to whom he paid $200 a month. But the evidence was staggering: five thousand financial documents and the testimony of insiders who described how bar records were altered or destroyed so that Frank and his partner could hide cash profits—$150,000 from one bar alone—and avoid paying taxes. One witness was worried about his health. “I don’t want to discuss anything,” he said. “I got my bod to worry about.” The former and present employees and dancers who did talk it up on the stand were described by Frank’s attorneys as thieves, drug users, and mental cases. In some instances, that may have been true. But the feds had the goods on Frank and threw in a few other trade secrets to boot. The “booze” that customers bought for dancers was known as “lady drinks” and was, in fact, sodas costing $3 a pop. And those “Amateur Nights” at the taverns, when anyone off the street could dance topless to win a prize? They were Frank’s dancers who came over from one of his other clubs. Frank’s Talents West agency also provided dancers to competing topless taverns as well, for a $500 monthly fee.

Among those who testified, reluctantly, in Portland against Frank was his former Bavarian Gardens manger, Gilbert Pauole. A convicted heroin dealer, he and Frank had shared a cell at McNeil Island, and Frank later hired him as a doorman and bouncer before making him a manager. “I look at Frank Colacurcio as my dad, my friend, and a very special person,” Pauole said during the trial. Frank was godfather to his son as well and had given Pauole a necklace with a gold charm shaped like a pepper, a symbol of his trust in Gil.

The feds made their case nonetheless, and Frank was convicted of conspiracy and tax fraud. In 1982 he was given four years in a Texas federal prison. He was sixty-five. Time to think of retirement.

But even before he was released from the Fort Worth pen, the feds and others were anticipating his return. Nothing had changed in Frank’s world, according to an IRS agent who appeared behind screens to conceal his face during 1985 crime hearings in New Mexico’s capital city, Santa Fe. Daryll Whitehead, who would be on Frank’s trail for years, said Colacurcio was piping orders to others who visited him in prison, and they had begun expanding into New Mexico. Whitehead, who had testified at Frank’s latest trial, told the Governor’s Organized Crime Prevention Commission that Frank, even while in prison, had taken over two Albuquerque bars—the Palomino Club and the Chapter 11—where, most likely, he was skimming profits. Typically, Frank moved in on financially troubled bars, offered to help them bring in topless dancers from his Talents West agency in Seattle, then ended up wresting control of the bar, Whitehead said.

Asked about all this, Frank’s Seattle attorney William Helsell said it wasn’t true. His client was a model prisoner, working in the kitchen, and was likely to serve every day of his term. “If the parole board treated him like everyone else, he’d be out by now,” said Helsell.

“They’re pretty unsympathetic to poor Frank.”