Nudity Inc., Inside Out

As one of the club co-owners told a lowly paid dancer who wasn’t gung ho about sex with strangers, “Well honey, you’ve got to get in there and compete.”

In a voluminous search warrant, FBI agent Corey Cote detailed how Frank’s organization operated and how it made as much as $12 million a year doing it. Son Frankie, as a co-owner, handled the daily paperwork and cash flow, reconciling discrepancies in revenue and receipts. Frank’s nephew Leroy Christiansen did some of the same duties and was also a co-owner, along with longtime partners Dave Ebert and Steve Fueston. Gil Conte, Frank’s former driver and friend, was the trusted money man, picking up the day’s receipts at the clubs and driving them to the Talents West offices. Julie McDowell had been a dancer and then manager at Rick’s for more than two decades, in charge of the girls, while bookkeeper Marsha Furfaro kept track of the debts run up by dancers. Talents West had run Sugar’s in Shoreline since 1982 and the other clubs—Honey’s in Everett, Fox’s in Parkland, and Rick’s, the largest and most profitable, in Seattle—since 1988.

At each of the four clubs, Cote said, “prostitution is rampant.” Dancers regularly were paid to engage in sex with customers, knowingly permitted by club managers. Frank and the owners received a cut from the illegal sex and benefited from the other revenue—the cover charge and soft drinks—generated by customers lured in by the sex. Taken together, this working relationship amounted to criminal conspiracy and racketeering, Cote said, based on evidence gathered by cops and agents posing as customers and employees. One female undercover agent was hired as a waitress and soon worked into a management position, all in a two-month stint. Five dancers who had already been paid as confidential informants by the cops were further employed to provide dirt for the task force. Several agreed reluctantly, it seems, agreeing to cooperate in return for dropping prostitution, drug, and morals charges. A man with inside knowledge of the business operations also provided details after receiving $500 for providing “historical information” about Frank’s operation. Several other dancers initiated contacts with police to tell what they knew, said Cote.

Rick’s was officially owned by Christiansen, Ebert, Fueston, and Frankie, according to testimony Fueston gave in another court case. For 365 days a year, customers flooded through the doors, doling out a $10 cover and observing the mandatory one-drink minimum, another five bills. The nearly eighty dancers who revolved through Rick’s and across its two stages usually paid $130 daily rent for the privilege to dance. At a less-popular club such as Sugar’s, the rent was around $75. Their income was made off customers who paid for private dances, particularly those in the darkly lighted VIP area with mostly hidden booths. Undercover cops watched customers have sex with girls and then leave condoms on the floor. Customers used their credit cards to buy tokens—Frank’s funny money—which were used like poker chips to pay for dances and drinks, tips and sex. The tokens were interchangeable at all four clubs. When performers cashed in the tokens, Frank and Co. took another 10 percent off the top. For example, said Cote, describing a typical transaction, “If a customer pays a dancer $50 for oral sex, the dancer will exchange the tokens for $45 and the club retains a $5 exchange fee.”

The feds considered the token exchange to be money laundering. They also claimed Frank’s club evaded city admission taxes by underreporting receipts from the cover charge. Rick’s would keep its count through a camera mounted inside the door, making it possible to tally the daily number of entering customers. The video count was necessary, said Frank’s bookkeeper Betty Howard in another court case, to make customer and money counts match up, so the admission tax could be correctly determined. “There have been employee theft problems in the past,” she said, “and we avoid that now by reconciling receipts with attendance.”

Investigators had their doubts and mounted their own video camera to a utility pole outside Rick’s, said agent Cote. It was a gotcha moment. Over a ten-month period, Rick’s reported about sixty thousand customers entering its doors. The feds’ camera showed the count closer to 122,000. They figured the club had scammed the city for about $32,000 in unpaid admission taxes. Considering the clubs were million-dollar-monthly operations, that seemed a paltry amount when compared against the risk. But no revenue source went untouched, legit or otherwise. During just 2006, according to agent Cote, dancer rent produced $3.8 million revenue at Rick’s alone. Hard-nosed managers still docked dancers their $130 even if they missed their shifts, the feds said. If dancers did show, but had a bad night financially, they were given a notice for the balance due. Those who owed back rent, said Cote, were often the ones who didn’t engage in sex. The clubs then used that as leverage, telling girls they had a better chance of paying what they owed if they’d just use their hands a little more. As one club manager told a lowly paid dancer who wasn’t gung ho about sex with strangers, “Well honey, you’ve got to get in there and compete.”

It had become clear to the task force that Frank was dominating the hand and breast market. He and his partners were raking in millions, Cote determined, after tracking credit card and ATM transactions at Rick’s for a sixteen-month period. From January 2006 through April 2007, Rick’s electronic cash flow came to $4.2 million. At Honey’s, the transactions came to $2.3 million; Fox’s was $2.1 million and Sugar’s $600,000. For the four clubs, that’s $9.2 million. Then there was the revenue from rent, chip exchanges, drinks, cover, and condoms—roughly another $6 million from the clubs. Led by Rick’s $7 million total revenue during those months, Frank’s four-club operation took in $15.2 million—close to $1 million a month, or $250,000 a week.

None of that money went to Frank—on the record, anyway. Cote and federal agents tracked $1.1 million in payments to Christiansen, Ebert, and Fueston each, with $1 million going to Frankie. But that was just the profits from Rick’s. Christiansen, Ebert, and Fueston each got roughly another $850,000 from the other clubs’ operations; Frankie got another $800,000. In sixteen months, each owner had made something close to $2 million.

To make this all work, said Cote, “the business model at each of the four strip clubs is the same.” Nudity alone wouldn’t bring in this kind of money, making sex the necessary component. “The essential element of this business model is the promotion and facilitation of prostitution,” he said. Sex brings in more customers, thus more girls are needed to service them. That drives up the rent and the chip revenue. If the girls were there to be seen but not touched, said Cote, the clubs would be the poorer for it. Said one dancer at Sugar’s, “If it wasn’t for the sex, most of the guys wouldn’t even come in.”

The VIP areas at each club facilitated the money flow through masturbation, oral sex, fingering, and now and then intercourse, investigators discovered. Dances might generally cost $20 to $30; with sex, they would cost $50 or more—that included a “hand finish” as the girls called polishing the knob. “It doesn’t make any difference if you come or not,” said one dancer. “If I rub your dick, it will cost $50.” Maybe less than half the girls at one club will engage in sex, and those who do, some engaging as many as a dozen men a night, don’t necessarily do it all. “I’ll rub you, I’ll suck you,” a dancer told a Pierce County undercover cop at Fox’s. “But I won’t fuck you.”

Records confiscated by the feds indicate club managers moved some girls—most in their twenties, but one a forty-six-year-old mom—from club to club after they were busted. It was done to provide Frank and his partners with “plausible deniability” in cases such as the pending federal charges, said Cote. Frankie and his cousin Christiansen doled out little in the way of daily discipline, Cote claimed, and tended not to fire any employees for gross violations. Some records revealed thousands of dollars in loans and back rent owed by dancers. They were paying off their obligations at $10 or $20 a month, leaving them in constant debt to the clubs. Personnel records for girls who went by the stage names of Jada, Janika, and Gypsy (another changed her nom de guerre from Kerri to Carmela to Meadow and back to Kerri) show such hand-written entries as “blow job” and “hand job,” and indicate the offender was moved to another club as a result. One dancer named Karma was reprimanded for “Having sex with customer—no protection at all. Standard for her. Both parents died from AIDS.” A manager wasted no words describing another dancer seen giving oral sex: “Regarding Tessa: Caught with cock in mouth.” Frankie apparently appreciated the brevity. “We’re all guys here,” he said later, discussing the note with an undercover officer posing as a manager, “so you can just be brief and to the point.”

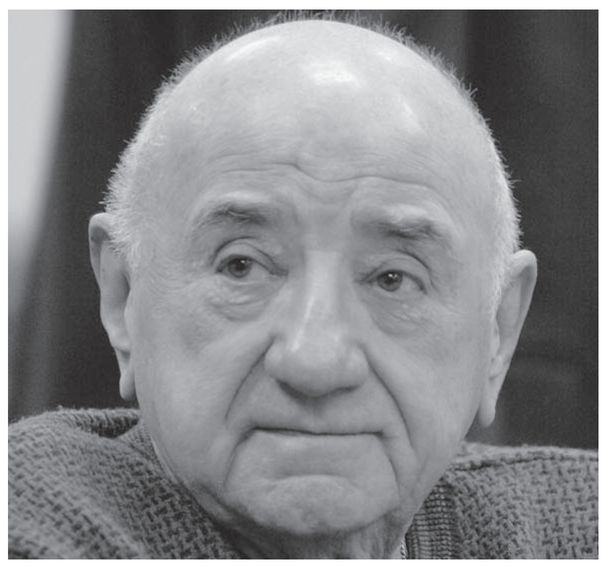

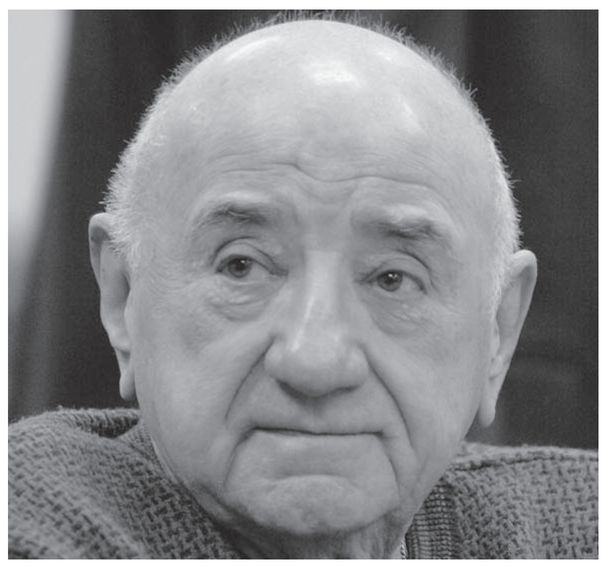

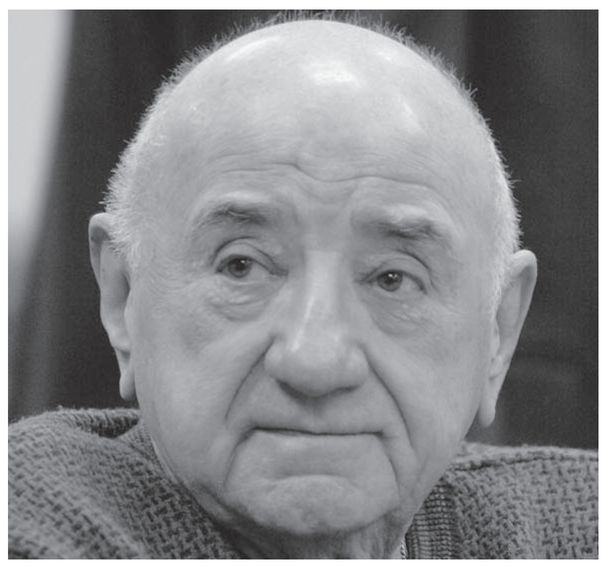

Frank Colacurcio Sr., 90, pleads guilty at the King County Courthouse in Seattle in the Strippergate case, January 28, 2008. (Photo: Ellen M. Banner/The Seattle Times)

For almost a year, Frank and the feds negotiated a plea or settlement to probable racketeering charges. It looked like an official indictment and trial would be avoidable if Frank and his partners gave up their dance joints—closed them, sold them, handed them over to the government for disposal—and disappeared.

“Frank’s finally feeling his age,” said an attorney familiar with the talks. “He’s tired and weak.” He was spending a good part of the day at home in his favorite leather chair, looking out at the lake as his ex-wife took care of the daily chores.

Nonetheless, he was strong enough to walk away from a settlement to head off an indictment in early 2009, keeping alive his, and a city’s, extraordinary history of vice. “There’s just nobody like this guy,” the attorney said, shaking his head. “He’s the last one.”