If you want to be strong, you must accustom your body to be the servant of your mind, and train it with toil and sweat.

Prodicus, On Hercules

ONE OF THE FIRST CONSTELLATIONS I learned to recognise was that of Hercules: a box of stars radiating flailing, half-bent limbs. Look for the Pole Star, then follow the tiny saucepan handle of Ursa Minor, and you’re not far off. As a child, I had a pop-up book about astronomy, and over starry bones it showed a greyed-out Hercules kneeling, club in hand, about to deal a death blow to the serpent Draco.

I knew the story of Hercules because my schoolteacher had organised a project on Greek mythology. According to the myth, Draco was a snake-like creature guarding an apple tree in a sacred garden when Hercules (or, as the Greeks named him, Heracles) clubbed him to death. I don’t remember her pointing out the parallels with the story of the Garden of Eden, but I do remember her asking us to make drawings of Hercules’s twelve labours. I sketched mountains of shit in the Augean stables, and puddles of blood under the Nemean lion (his ‘thirteenth’ labour, the impregnation of fifty virgins in a single night, was never mentioned). He was so strong, the teacher said, that when a superhuman being called Atlas tired of holding up the heavens, Hercules was the only mortal powerful enough to take on the task.

In the most usual telling of the myth Hercules was the son of Zeus, result of one of his many illegitimate affairs. Zeus’s wife Hera tried to prevent the birth, directing magic spells at Hercules’s mother while clamping her own thighs tightly together. This was an integral part of the spell, and Hera was tricked into uncrossing her legs; the enchantment broke, and Hercules survived his first labour. It was immediately apparent that the boy was strong: in his cot he strangled the snakes that Hera sent to kill him, and the prophet Tire-sias augured that he would accomplish great deeds.

HARRY ALKMAN ABUSED anabolic steroids. It wasn’t his muscles that gave me the clue, but his skin: no matter what treatment I gave, his acne remained disastrous. I tried everything in the armoury: lotions and astringents, antibiotics and vitamin A, but his shoulders, neck and cheeks continued to erupt with pustules which scarred to pits, as if raindrops had fallen on the dust of his skin. I was new to medicine when we met, with an innocent belief in my patients’ honesty. While discussing Harry’s acne at a coffee break one day, a more experienced colleague suggested: ‘Ask again what else he’s taking.’

At our next appointment I asked Harry if he was sure he never took anything I hadn’t prescribed; he confessed he’d been buying steroids online for the last four years. ‘Which one?’ I asked.

‘One?’ he said, surprised by my ignorance. ‘No one takes just one.’

‘Well, what do you take?’ ‘Well, I started with testosterone and some Dianabol. That’s to bulk you up, for the first twelve weeks. And also anastrozole to stop man-boobs.’ I knew anastrozole as a hormonal treatment for women with breast cancer.

‘And then?’

‘Well, that depends on what you want to achieve. To get more definition you’d usually switch the type of testosterone, and add in something like Anavar. But keep going with the anastrozole.’

‘So you said that’s for starters. What do you take once you’ve moved up a level?’

‘There are plenty of schedules out there,’ he said, ‘Masteron, Equipoise, Decanate, Nandrone, human growth hormone …’

I interrupted: ‘Your acne won’t get better until you stop taking those steroids. They’re making your skin oily, which brings on the spots and scarring.’ I ran through some of the other risks of steroids: heart failure through its effect on cardiac muscle, diabetes, infertility, depression, uncontainable bouts of rage. He listened politely; in his lap I could see the skin over his knuckles tightening and relaxing.

‘If you don’t want to help me with my acne just say so,’ he said finally. ‘But I know what I’m doing. I’ve never felt better.’

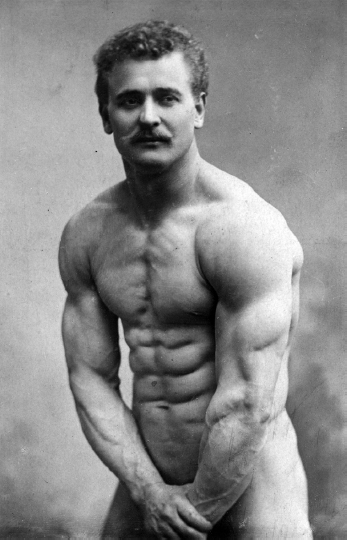

THE FIRST BODYBUILDER in the modern sense was a nineteenth-century German circus strongman called Friedrich Müller, who adopted the stage name Eugen Sandow. He claimed to have been inspired by a famous Roman statue of Hercules, the ‘Farnese’. In his manifesto ‘Body-Building’, Sandow coined a phrase as well as an industry – to emphasise the self-improvement ethos of his new sport, he subtitled it ‘Man in the Making’. He patented a regime of clean living and weight training that resonated with the fin-de-siècle obsession with colonial strength and self-determination. In 1901 he conceived a public contest to find the world’s best physique: it was organised at the Royal Albert Hall in London, and judged by the author and physician Arthur Conan Doyle and the sculptor and fitness enthusiast Charles Bennett Lawes. Opening the show was a troupe of gymnasts from the London Orphan Asylum. The contestants paraded on stage, dressed in black tights and animal skins, striking poses from famous statues of antiquity. Sandow presented the winner with a golden statue of himself holding a Herculean pose.

Sandow must have had immense willpower; he claimed he had been a weakling until he was inspired by the statue of Hercules to build up his muscles. He sold his patented techniques by mail order, and from the outset his aim was an aesthetic one: mimicry of classical statuary rather than feats of particular strength. In the journey from circus strongman to the Albert Hall he made a leap of respectability; adopting classical motifs gave the endeavour a dignity and acceptance which broadened its audience. That audience grew exponentially with the advent of cinema: after 1910, Italian films like Cabiria, Marcantonio e Cleopatra, and Quo Vadis? all led with Herculean muscle-men, and borrowed heavily from the classics. The films were phenomenally successful across Europe and the United States, and their actors became celebrities – feted for their muscles rather than their acting skills or good looks. By the 1960s, the films were epic in scope: Steve Reeves’s Hercules and Hercules Unchained set the tone for bodybuilders as actors. Others followed: Arnold Schwarzenegger (Hercules in New York), Mickey Hargitay (The Loves of Hercules) and Ralf Moeller (Gladiator).

In his memoir The Education of a Bodybuilder, Arnold Schwarzenegger wrote of how at the age of fifteen he first visited a gym in Austria and became intoxicated by the idea of transforming his body. The men who took him on as a protégé were huge, brutal but profoundly admirable – he sought specifically to emulate their ‘Herculean’ looks. His account of his first summer in the gym is steeped in a kind of sexual intoxication: Schwarzenegger felt turned on by the feeling of his muscles expanding, and dreamed of growing ever more gigantic. He modelled his own training schedule on that of the bodybuilding actor Reg Park (star of Hercules and the Conquest of Atlantis). Park advocated a kind of sculptural bodybuilding, which involved first pumping the muscles up, and then finessing the definition of each one.* Like an autoerotic Pygmalion, Schwarzenegger fell more deeply in love with his body as he sculpted it.

On the subject of steroids, Schwarzenegger is coy: his Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding slips a discussion of performance-enhancing drugs into the last couple of pages. Every great bodybuilder uses steroids, he declares, but they do so only as a final polish to a body already honed to near-perfection through effort. Steroids, he says, are essential if you want to keep your edge – an edge as much mental as physical. The drugs don’t just help build muscle faster and stronger, they bring on an aggression that facilitates a ferociously competitive attitude to training.

FROM MY DESK I usually had warning that Harry Alkman was coming to clinic – his voice like a chain-gang foreman carrying from the hallway as he argued with the receptionists, or his dogs barking outside as he chained them to the surgery steps. He had three Staffordshire bull terriers – pale, muscled and belligerent.

After the conversation about his acne I didn’t see him for a few months. The next time I heard those dogs barking, I went out to the waiting room to find him sitting with his girlfriend Tanya. She was silent in the corner: pale, and nervous, her ginger hair straggling over a grey tracksuit top. Harry sat with legs spread, occupying the space of three chairs. The cloth of his T-shirt bulged as if crammed with snakes.

‘You’ve got to help him with his temper,’ Tanya said tentatively, as they sat down together in my office. Her voice was like a child’s whisper. ‘It’s getting out of hand.’ Harry’s skin looked better, and I asked if he was still taking steroids.

He laughed. ‘Maybe I tried a new regime,’ he said.

‘He won’t listen to what I say,’ said Tanya, her eyes pressing on me.

‘To be honest, he doesn’t tend to listen to me either,’ I said.

A few nights previously they had been having an argument and Harry had lashed out at her; she dodged, and his fist hit the wall. The impact snapped a bone. He held up the hand as evidence, bandaged in the emergency department. ‘See what she made me do? You’ve got to give me something to calm down.’

‘You’re responsible for your own actions,’ I said, as calmly as I could. ‘And if you cut out the steroids you’ll get less angry.’ I reached down into the drawer for a leaflet titled ‘Alternatives to Violence’, circled the phone number on the front, and handed it over. The leaflet carried a portrait of a pensive young man, heavily muscled, above the legend: ‘Be Who You Want To Be: Respect yourself, Listen to others, Get on with people.’

‘You have to stop those steroids,’ I repeated. ‘And Tanya, if he threatens you or hurts you – phone the police.’

She came a week later without him, and I told her about the local women’s shelter where she could go if she ever felt unsafe at home. She already had their number.

THERE’S YET ANOTHER VERSION of Hercules’s myth, dramatised by the Greek playwright Euripides, in which, on the completion of his twelve labours, Hercules returns home to his wife Megara and their three sons. In this telling, Hera can’t bear to see Hercules happy after his labours, so from her viewpoint on Mount Olympus she sends a furious madness upon him. Euripides describes the change: ‘He was no longer himself; his eyes were rolling; he was distraught; his eyeballs were bloodshot, and foam was oozing down his bearded cheek. He spoke with a madman’s laugh.’ Hera’s spell makes Hercules believe that Megara and his children are enemies; boiling with rage he turns on them. He slaughters one son with an arrow; his second son pleads with him but Hercules, absorbed in his frenzy, clubs the boy to death and tramples on his bones. He then turns on his wife and third son, shooting a single arrow through both bodies. Finally, his family slaughtered, he turns on his foster father Amphitryon but the goddess Pallas intervenes, hurling a rock at his breast. As it hits home his ‘frenzied thirst for blood’ fades; he falls to the floor and into an enchanted sleep.

MANY CULTURES HAVE STORIES of muscle-bound strong-men, unhelmed by fury. In medieval Norse culture these men were much valued in battle: they were called ‘berserks’, or ‘bear-shirts’, transformed by their bloodlust to become as much bears as men. The Germans too had a word for that altered state: ‘mordlust’, a lust for death. The Anglo-Saxons had Beowulf; the Irish, Cú Chulainn; in Hindu mythology, Krishna; for the Babylonians, Gilgamesh. There are resonances and echoes with the battle-trance of Achilles. The Hebrew Bible has the story of Samson, a Herculean strongman who, like his Greek counterpart, kills a lion with his bare hands, pulls down buildings and lays waste to an army (but where Hercules has his bow and arrows, Samson is armed with an ass’s jawbone). Just as the Greek myth gives Hercules three earthly ‘wives’ in quick succession, the Hebrew story offers Samson the same.

Anabolic steroids can make an already irascible temper far worse – there are a few accounts in the medical literature of murder committed under their influence. Weight training without steroids can enhance well-being by boosting testosterone, but it can also intensify background aggression. A study conducted in a male prison showed that the most aggressive men had higher testosterone levels. Men born with doubled ‘Y’ chromosomes instead of the usual single ‘Y’ don’t just have more testosterone, there is some evidence to suggest that they are over-represented in the prison population, possibly through greater propensity to short-tempered violence. Anecdotal evidence suggests that when adolescent boys are in the midst of the testosterone boost of puberty they get into more fights, and become more argumentative at home. Like the madness of Hercules, unnatural levels of testosterone can ignite furies that consume the individual, even as they threaten everyone around him.

MEN WHO TAKE ANABOLIC STEROIDS for a length of time usually become infertile, because artificial testosterone inhibits the body from making its own. Their testicles shrink, and their sperm count drops. As if in awareness of the paradoxical effects of excessive testosterone, many of the greatest strongmen in mythology pass through a phase of feminisation: Thor goes through a period dressing as a woman, as does Krishna. One of the Greek myths of Hercules tells that in one of his three marriages he stayed home to cook and clean, while his wife went out hunting and fighting. In one version of the story of the Trojan War, Achilles’s mother tries to keep him home by dressing him as a girl (he is betrayed when the Greek army passes through the village, and he can’t resist fondling their weapons).

The next time I saw Harry there was no warning – no barking of dogs, no yelling at the reception desk. He was sitting quietly in the waiting room when I went to call him, wearing a loose hooded sweatshirt. As he sat down in the chair of my office, he placed a piece of paper on the desk.

‘What’s this?’ I asked.

‘My new regime. I’ve come to see what you think.’

The piece of paper had a list of medications on it, and none of them were anabolic steroids.

‘So have you stopped taking testosterone?’ I asked him.

‘Yep – I’ve brought it down slowly. Tanya and I are going to have kids. I’ve come to see if you’ll help.’

‘Well, I can’t prescribe any of this stuff for you – most of these are IVF drugs for women. They’re not licensed for use in men.’

‘I don’t need you to prescribe them for me – I’ll get them and inject them myself. I just wanted to know what you think of the regime, and if you’ll send the sperm count test afterwards, to see if it’s worked.’

Harry had it all worked out: his research had told him to arrange a week of daily injections with a hormone to stimulate his testicles. Then he’d start a drug which in women leads to hyperovulation, but in men can kick-start the production of sperm. Anastrozole was on the regime again – this time to prevent Harry’s natural testosterone being converted into oestrogen by the body.* The sperm he produced would at first be very sluggish, so after a month he’d take a fairly low dose of another drug to promote agility and mobility of the new sperm.

I phoned a colleague who specialises in endocrinology – the study of hormones – to ask him about the regime. ‘Will it work?’ I asked him.

‘Sadly, it probably will,’ he said. ‘But most bodybuilders do this every so often, just to make sure their testes are still working. As soon as they get the reassurance of a normal sperm count, they go back on the steroids.’

BODYBUILDING COULD BE DESCRIBED as a species of addiction, both to the mental rush when blood surges to the brain fresh from swollen muscles, known as ‘pump’, and to a body shape perceived to be superior. A couple of decades ago it was thought of as a modern neurosis – a ‘body dysmorphic disorder’ responding to a contemporary crisis in masculinity. For some bodybuilders there may be a fragment of truth in that, but Eugen Sandow and Arnold Schwarzenegger are emblematic of a dream that has been around for as long as humans have admired strength.

In most of the Greek myths of Hercules he is born strong, but in a story recorded by Xenophon, one of Plato’s pupils, there was a moment in the hero’s adolescence when he had to make a choice between a life of strength or a life of ease. Walking along a path one day, Hercules encounters two women who present him with a decision. He could choose a path of comfort through life or a path of difficulty. The path of difficulty would require great effort but would result in a commensurate measure of honour. He could be strong, but that strength wouldn’t come as the free gift from a god or through taking a drug – it would come only through the exercise of will. He chose the path of difficulty: ‘For of all things good and fair, the gods give nothing to man without toil and effort.’