For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

I HAVE A PATIENT who believes her fingers are rotting. Usually Megan offers me her fingertips for inspection. Her unclipped nails are thick with grime, and more than once I’ve led her to the sink where together we’ve scrubbed them with a nail brush. ‘Can’t you smell it?’ she asks me, ‘they’re disgusting.’ I don’t smell or see anything unusual. Megan is sometimes tormented by bullying and insulting voices, and when those voices are strong, so are the hallucinations of rot. We meet at least once a month: for me, it’s a chance to check how she’s getting on; for her, it’s to pick up her antipsychotic drug prescription. She finds the drugs helpful; the consultations, I think, less so. I’ve tried exploring what the rotten fingertips might mean for her; whether they’re a symbol of some rot or canker that gnaws at her mind rather than her fingers. ‘Nope, there’s nothing symbolic about it,’ she says. ‘They really stink. I can’t believe you can’t smell it.’

In Greek the word ‘psyche’ means ‘soul’ or ‘life’; ‘psychosis’ means ‘animation’ or ‘infusing with life’. For nineteenth- and early twentieth-century psychiatrists it meant something different: ‘psychosis’ was madness arising from a disorder of mind, as opposed to ‘neurosis’, which arose from a disorder of nerves (this is now recognised to be a meaningless distinction). Today the word is reserved for those who hold beliefs and report hallucinatory perceptions that are manifestly untrue – those who’ve lost touch in a particularly damaging or distressing way with what’s verifiably real. In Dementia Praecox, or the Group of Schizophrenias, published in 1911, psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler coined the term ‘schizophrenia’ to describe a group of mental illnesses that suggested this loss of grip on reality. His book affirmed that when delusions or hallucinations become prominent, ‘everything may seem different; one’s own person as well as the external world … The person loses his boundaries in time and space.’ In schizophrenia, this loss of boundaries can become enduring, life-limiting and profoundly distressing.

When people take hallucinogenic drugs for pleasure, that pleasure is contingent on the change they offer being temporary. Aldous Huxley’s Doors of Perception, an essay exploring the effects of taking four-tenths of a gramme of the hallucinogenic drug mescaline, took its title from William Blake: ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.’ For Huxley, the brain was a reducing valve, optimised to restrict the glory and plurality of the world. He took hallucinogens with the intention of blowing open that valve, and specifically noted that the drug gave him an ‘inkling’ of what it might feel like to be psychotic. He wanted to induce a transformed state of consciousness, and shortcut through to the ecstatic states of mystical religion like those described by practitioners of Zen Buddhism, in which perceptual boundaries are said to be similarly dissolved.

The idea that drugs could offer transcendence was criticised by the Zen master D. T. Suzuki, who insisted that hallucinogenic drugs gave an insight only into a ‘devil’s sphere’ of reality. Taking LSD, Suzuki is quoted as saying, ‘is stupid’. ‘These drugs conjure up “mystic” visions,’ he wrote, ‘[but] Zen is concerned not with these visions, as the drug-takers are, but with the “person” who is the subject of the visions.’ Suzuki’s student Koji Sato took a different view: hallucinogenic drugs gave access to a mental state in which students ‘should not linger’, but from which much could be learned. Sato tells the story of one Zen student who couldn’t progress beyond a series of Buddhist koan teachings until he took LSD; following his drug experiences, he ‘passed these koans easily’.

It seems a universal that human minds seek to move in and out of alternative worlds, altering their state of consciousness. Children accomplish these transformations through play, but with adults, drugs are an almost ubiquitous feature of human communities, whether to transform perspective, become energised or to relax. Almost every society has a tradition of using drugs, and the few without tend to have developed alternative means of accessing hallucinatory states such as fasting, or prolonged meditation.

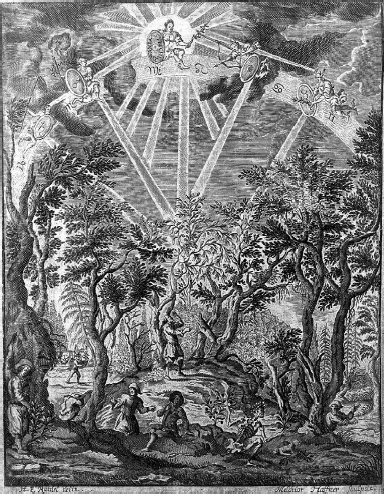

Broadly speaking, to be an hallucinogen, a drug must induce a distortion of perception without acting as a sedative or stimulant. There are many natural hallucinogens, and their use by humans has been described as far back as the Hindu Vedas – about 5,000 years. In the Middle Ages there were periodic outbreaks of a condition known as St Anthony’s Fire, in which whole communities experienced hallucinations when they ate bread contaminated with ergot alkaloids. The alkaloids are generated by a fungus that grows on grain; in the gut they cause diarrhoea and vomiting, and in the brain they can cause headaches, hallucinations and seizures. A similar effect is brought on by ingesting the leaves or berries of deadly nightshade (‘belladonna’). One seventeenth-century treatise on belladonna poisoning emphasised the religious and mystical nature of the hallucinations – prefiguring Huxley’s Doors of Perception.

There are many other natural drugs that have hallucinogenic effects, like the psilocybin of mushrooms, and the peyote of Meso-American cacti. But the most powerful hallucinogen of all is a synthetic one, Lysergic acid, or LSD. It’s active in tiny doses, about a thousandth of the equivalent dose of mescaline, making it one of the most powerful drugs known: 10μg can produce a feeling of euphoria, and as little as 50μg an hallucinogenic effect.

LSD was first synthesised in 1938, but its effect wasn’t discovered until 1943 when, while working in the laboratory, the Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman accidentally absorbed some through his fingers. He thought he had died and been transported to hell. The drug has wide-ranging effects across the brain, and scientists couldn’t figure out how it transformed vision, hearing, smelling and dreaming without dulling or heightening the taker’s level of consciousness. In the 1950s and 1960s it was trialled as a therapy for alcoholism, for depression, even for schizophrenia, but few studies have been able to prove any enduring therapeutic benefit. More recently, the psilocybin of hallucinogenic mushrooms has been proposed as an aid to deepen engagement in psychotherapy, much as Sato’s Zen student passed the most difficult koans only after taking hallucinogens. But LSD is not without danger: many studies show a small, persistent risk of psychotic reactions to the drug – around 1 or 2 per cent. It seems that LSD-induced visions can cede to hallucinatory states that persist long after the drug itself has been eliminated from the body.

MY INTRODUCTION AS A MEDICAL STUDENT to the horror of drug-induced psychosis was Dan, a young student of philosophy I met during a psychiatry attachment. After taking LSD for the first time, Dan had a psychotic reaction with persistent hallucinations, and disabling panic attacks. I spent a couple of hours talking with him about his experience. He was short, with blonde curls to each side of his forehead like question marks, and a vertical line between his eyebrows like an exclamation. Angry patches of acne erupted between the sparse bristles on his cheeks.

He told me that he took a tab of the drug one evening in his bedroom, out of curiosity. The first thing he noticed, within twenty minutes or so, was that his bed was breathing, the quilt was rising and falling in time with his own breath. He tried to write down ‘the bed is breathing’ on a piece of paper, but the sensation of the pen on paper was all wrong, as if the nib was sinking through into the wooden desk beneath. Lying down on his bed he glanced up out of the window, and noticed that the sky was pulsing between light and dark. ‘It wasn’t frightening at first,’ he said, ‘but beautiful’; he lay for a while mesmerised by the change. He knocked on his flatmate’s door to tell him about the vision but found that instead of words, only giggles would come out. ‘Every time I tried to speak it was as if I had to line the words up beforehand in some antechamber of my mind,’ he said, ‘then blurt them out. But they wouldn’t come.’ On a trip to the toilet he saw his urine as fluorescent green blobs on the porcelain, beautifully bright, like scales on a dragon-fly. As he watched, they seemed to spiral in a vortex towards the base of the pan before melting away.

At first the drug made him feel exhilarated and euphoric: he wanted to go out and enjoy his new perceptions. He strode out for a walk around the neighbourhood, but the euphoria quickly melted: his feet on the pavement seemed to sink into the cement; the music playing through his earphones began to boom from the brick walls of the buildings around him. His exhilaration yielded to a creeping, desolating anxiety. Beneath the hood of a pedestrian he glimpsed the flashing impression of a skull. Every piece of chewing gum trodden into the pavement glowed red, green or amber depending on the light showing at its nearest traffic lights. A panic attack came over him, bringing a toxic paranoia: every car looked like a police car, every pedestrian seemed like a threat.

He cut the walk short and, running back to his flat, noticed that the drug had done something to his body temperature – he was overheating. Once back in his room he stripped off all his clothes, and sat naked in the middle of the bedroom. ‘I kept telling myself, “What can happen to you? You’re here, on your bedroom floor, nothing bad can happen”’. But a great deal was happening: the edges of the posters on his walls were moving, scraps of paint on the wooden floor seemed to writhe like larvae, and when he looked down at his skin, it seemed to swirl in endless migration over its own surface. ‘It was terrifying to see that even my body wasn’t safe,’ he said. ‘But it was also horribly fascinating: my hand would transform between looking old, wrinkled and weak, then it’d become strong, youthful and powerful. And if I looked in the mirror I’d see the same rapid change, backwards and forwards, on my face.’

Dan sat for hours like that on his bedroom floor, too scared to switch off the lights and sleep, terrified to leave the room. ‘I felt as if I’d passed my whole life perched on a plinth in a central chamber of my mind,’ he said. ‘Stable and secure. That night I was kicked off, and left hanging by my fingernails over some awful chasm. I knew that if I let go, I’d go mad.’

By sunrise the following day he was still flinching at unexpected auditory hallucinations, distrustful of every sensation – even the hard pressure of the floor beneath him. Music would blare loud then become muted, and he flinched at flickering shadows on the edges of his vision. Sleepless now for thirty hours, his paranoia was intensified by exhaustion: he became overwhelmed by terror at the prospect of going outside. His flatmate called the GP, and then accompanied him to the local clinic. The GP sent him in a taxi to the emergency psychiatric team at the local hospital, where he sweated, trembled and stared at the floor until he was seen.

‘They told me it would fade with time and they were right,’ Dan said. ‘They gave me some drugs – sedatives – that brought such relief. The first one I took was like honey on my brain.’ The psychiatric team arranged to see him again the following day – he didn’t need to be admitted into the hospital ward. The new drug slowed him down, his thoughts became viscous, and he had to stop attending the university. But within three weeks he had reduced the dose to a negligible amount, and was learning to breathe through the panic attacks. Out on the street he still saw skulls on people’s faces, but was finding ways of ignoring the visions and distracting himself. Speaking to medical students like me was one of the ways in which he was trying to understand his experience, and reclaim his mind.

THE PSYCHIATRIST R. D. LAING spent many hundreds of hours listening to personal accounts of psychosis. There are striking similarities between his case reports and accounts like Dan’s of a terrifying LSD trip. In The Divided Self Laing quotes one of his psychotic patients: ‘I’m losing myself. It’s getting deeper and deeper. I want to tell you things, but I’m scared.’ In his book Disembodied Spirits and Deanimated Bodies, Italian psychiatrist Giovanni Stanghellini quotes a patient undergoing a similar kind of ‘ego disintegration’: ‘All sensations seem to be different from usual and to fall apart. My body is changing, my face too. I feel disconnected from myself.’

There’s a theory about schizophrenia that proposes psychosis as a disintegration of the moment-to-moment synthesis between the different social and mental roles we inhabit – a synthesis we all carry out unconsciously, and which hallucinogens temporarily disrupt. From this perspective, psychosis and hallucinogenic drugs break the tiller that allows us to navigate between inner and outer worlds. Each of us is composed of bundles of different identities, and we are subject to ceaseless torrents of sensory awareness; in psychosis the ability to create wholeness from that turmoil breaks down. Images from functional MRI scanners are notoriously difficult to interpret and the technology is still in its infancy, but when the brains of LSD users are visualised, networks of neurons that under normal circumstances all fire together can be seen to become desynchronised. It may be an insight into how those many selves that constitute our being can be shattered apart.

Dan found a way back from the edge of disintegration and his breakdown, though provoked by a drug, gave me a glimpse of what some of my patients with schizophrenia, like Megan, might be going through. Hallucinogens can offer visions but risk division of the self, and for Albert Hoffman, Dan, and for D. T. Suzuki, those visions are a ‘sphere of devils’. But for many users the effects are pleasing, compelling, addictive, even heavenly. Precisely because they are temporary, they offer some an escape when life feels tedious, and bring breadth and richness when it feels narrow or impoverished. But it’s a fragile heaven they offer: dissolving the boundaries of experience may become a dark hell of terror. To reassert the boundaries of perception is to offer a path back to the light.