A Storm in Cincinnati

Quite seriously Rod, if you really want to go places with your television writing you ought to live in New York or Hollywood and not stay permanently in Cincinnati. I am pretty sure you realize this yourself, but don’t know what can be done about it at this point.

—LITERARY AGENT BLANCHE GAINES, MARCH 19, 1952

Without Cincinnati you don’t get to the next level of Rod Serling. He took all his experiences—growing up in Binghamton, his war experiences, his college experiences—and worked through them in Cincinnati. Cincinnati is the door that leads to everything else.

—TELEVISION CRITIC MARK DAWIDZIAK

Cincinnati adopted Rod Serling. This proprietary embrace did not happen immediately, of course. First Serling had to endure a year or so of anonymous drudgery, working as a radio staff writer. But eventually, when he began to regularly sell scripts to national radio and television series, he became “Cincinnati’s own Rod Serling”—local boy makes good. When one of these scripts was scheduled to be produced, the event was usually trumpeted by a piece in the Cincinnati Enquirer or the Post or the Times-Star, usually with Serling’s name in the headline. “Cincinnatian Rod Serling” was touted as “Cincinnati’s one-man script factory,” and the Cincinnati-based Writer’s Digest anointed him the “Mid-West’s Top TV Scripter.”

But first there was WLW.

After graduating from Antioch, Serling was hired by the Crosley Broadcasting Corporation as a continuity writer for WLW radio and later television. Dubbed the Nation’s Station, WLW was one of the bigger employers in radio in the region. According to John Morris, who produced many of the programs on which Serling worked, Serling arrived and proclaimed, “My one ambition is to be half as successful as my brother,” who was writing for United Press International.1 He soon began to dream of bigger things, however, and quickly discovered that being a staff writer was “a particularly dreamless occupation.”2

He wanted to write meaningful drama, but drama, meaningful or otherwise, was simply not part of WLW’s format.*

Serling spent most of his time at WLW writing advertising copy, biographical histories of local towns, and skits for series with titles like Midwestern Hayride and Straw Hat Matinee as well as a fifteen-minute, twice-weekly television sitcom he created, Leave It to Kathy, which was described in its narrated introduction as “the trials and tribulations of Kathy and her sidekick, Vera, as the two girls face life (and irate customers) from behind the complaint desk at Goober’s Department Store.” After writing all day for WLW, Serling would return home and work late into the night on his own dramatic scripts. In his first book, Patterns, he recalled, “I used to come home at seven o’clock in the evening, gulp down a dinner and set up my antique portable typewriter on the kitchen table. The first hour would then be spent closing all the mental gates and blacking out all the impressions of a previous eight hours of writing. You have to have a pretty selective brain for this sort of operation.”3

In addition to his “selective brain,” Serling possessed enough physical and mental energy to churn out an impressive quantity (if questionable quality) of scripts. Jack Gifford, a fellow staff writer at WLW, remembered that whenever the staff gathered socially, Serling “would always be the first to leave. He would always say ‘I’ve got something in the typewriter.’ The guy had fantastic energy. He never stopped.”4

While Serling found the subject matter at WLW unfulfilling, he was also frustrated by the anonymity that was part of being a staff writer. “Rod was very upset at the station because he couldn’t get name credit for anything he wrote,” Gifford recalled. “At least once a week—there were three of us—we would march down to the Program Director’s office and ask for two things: name recognition on our shows and a raise. And the answer was no and no.”5

To find an outlet for the kind of stories he was desperate to write, Serling needed to approach one of WLW’s competitors. Across town, WKRC-TV had begun broadcasting a weekly dramatic series produced entirely in Cincinnati and using exclusively local talent. The series ultimately dramatized all of what Serling called his “special preoccupations and predilections,” including his sentimentality regarding Christmas, his nostalgia, his deep-seated feelings about the horror of war, his views on the dehumanizing nature of prizefighting, his disdain for prejudice, even time travel.6 The series, which represents the most significant part of Rod Serling’s lost catalog, was called The Storm.

Given how clearly The Storm can be seen as a precursor of The Twilight Zone, it is surprising how rarely and how superficially it has been discussed. Two episodes of the series have explicit connections to The Twilight Zone, The Storm ventured into the realm of science fiction and/or fantasy no fewer than seven times, and it produced several stories that employed the type of ironic twist ending for which Serling became known.

One reason The Storm has rarely been discussed is obvious: few episodes survive. Another reason is that Serling rarely discussed it. In a lengthy 1957 essay about his earliest days in television, Serling wrote about his first network sale in 1950 and acknowledged several people who helped him along the way, including producers Worthington “Tony” Miner and Dick McDonagh, and his agent, Blanche Gaines, yet never mentioned The Storm or the man who helmed this series, Bob Huber.7 Serling and Huber remained friends and collaborated professionally on several occasions, and correspondence between the two men does not suggest any creative or personal conflicts. A bit of dialogue from Serling’s touchstone teleplay, Kraft Theatre’s “Patterns,” may suggest an explanation for why Huber and The Storm have been virtually erased from Serling’s history, however.

“Patterns” tells the story of Fred Staples, a young executive from a small Cincinnati firm who is hired to work for the Ramsey Company in New York City. Before reporting for his first day at his new position, he asks his wife, “How do I look?” She straightens his tie and replies, “Not a trace of Cincinnati.”

While living in Cincinnati, Serling occasionally flew to New York for script conferences with producers and advertising agencies. He found the experience intimidating: “Every time I walked into a network or agency office, I had the strange and persistent feeling that I was wearing overalls and Li’l Abner shoes.”8 When he first began taking these trips, he hid the fact that he had flown in from Cincinnati, hoping to give the impression that he lived in New York City. In 1954, when Serling relocated to Westport, Connecticut, (the same town where Staples and his wife settle), he wanted to make sure that no traces of Cincinnati remained. As author and television critic Mark Dawidziak put it, “It’s like they say about stand-up comedians—they need someplace where they can go and be bad. Someplace off the path, where they can work out their material, find out what works, what doesn’t, and not be afraid to fail. Cincinnati was that place for Serling.”9

Though the town had embraced him, and Rod and Carol Serling publicly claimed fond memories of their time in Cincinnati, Rod Serling later confessed privately that he viewed the city and his time there as little more than a stepping-stone on his way to bigger and better things.10 The Storm provided Serling with a testing ground for ideas. He viewed these productions as rough drafts that he could subsequently polish and shop to the networks. Indeed, at least a dozen of Serling’s scripts for The Storm were later produced on national network series.

Although The Storm had a miniscule budget and a substandard performance space, the quality of the show’s productions frequently impressed local critics. On November 15, 1951, Mary Wood of the Cincinnati Post wrote, “From several standpoints—production, acting, and scripting—the program consistently holds its own with the network’s [programming]. As a matter of fact, a number of ‘The Storm’ scripts, written by Rod Serling, have the fresh, imaginative approach to television that the early Norman Corwin writing gave radio.”11

The series debuted live on May 11, 1951, with “Ambassador of Death,” an episode written by Edith S. McGinnis, who also authored the next three episodes. McGinnis had submitted these scripts to WKRC-TV unsolicited as a way of pitching the idea that the station try to do an original dramatic television series. On the basis of these episodes, TV Dial Magazine presented the series with an award for Pioneering Drama in Local Television.12

Then Serling came along. Or, rather, along came R. Edward Sterling. To avoid conflicts with WLW, Serling’s initial contributions to The Storm were credited to this barely disguised pseudonym. Even after Serling resigned from WLW in September 1951, he continued to use this pseudonym on The Storm while using Rod Serling on scripts that he sold to WLW, thereby avoiding the appearance that the same writer was working for competing stations.13

On July 9, 1951, Leave It to Kathy debuted on WLW-TV with a story about gullible Kathy falling for a pretentious and penniless actor while her best friend, Vera, tries to unmask the man as a freeloader. The following night, WKRC aired Serling’s first contribution to The Storm, “Keeper of the Chair.” Had Serling received both credits under the same name, viewers might have had trouble believing that the two programs had been written by the same person. “Keeper of the Chair,” like virtually all of Serling’s scripts during this period, was initially written for radio. It was the story of a prison guard who, after ten years of supervising executions on death row, is haunted by the question of whether he has ever executed an innocent man. The first of Serling’s significant dramatic scripts produced on television, “Keeper of the Chair” also marks the first time in his professional career that he delved into a potentially controversial social issue (in this instance, capital punishment). This story, however, is not a polemic but instead deals with the potential human effect of capital punishment on the person responsible for flipping the switch. Serling believed that “some part of the executioner died with each execution.”14 He likely had similar views about those who kill on the battlefield and those who inflict punishment in the boxing ring. Serling’s combat experiences had left him with a deep concern for the effects of violence on the human psyche, and he frequently revisited the idea that the brutalizer and the brutalized can suffer reciprocal forms of dehumanization.

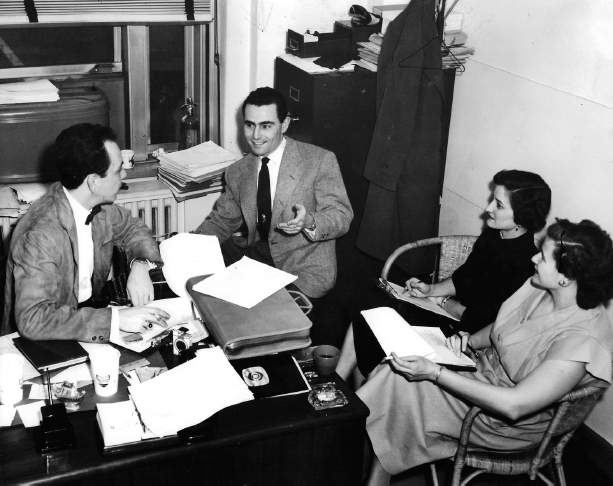

Rod Serling at a script conference with Bob Huber (left), WKRC Studios. Courtesy Cincinnati Enquirer; photo by Lawrence G. Phillips.

With a protagonist whose senses and memories have become unreliable, a one-step-from-reality tone, and a twist ending, “Keeper of the Chair” could be considered Rod Serling’s first Twilight Zone story produced on television. Another episode of The Storm has more direct ties to Serling’s best-known work, however. In June 1958, as The Twilight Zone was in development, Serling told the Cincinnati Enquirer, “Guess where I’m getting my opening story. From a script I wrote for the old ‘Storm’ series that was dramatized in Cincinnati years ago.”15 The story to which he had referred was “The Time Element.” Initially produced on The Storm on December 11, 1951, “The Time Element” tells the story of a man who believes he has been traveling back in time to the eve of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Serling expanded this script from a half hour to an hour and submitted it to CBS under the title “Twilight Zone—The Time Element.” Though it ultimately aired not on The Twilight Zone but on Desilu Playhouse (November 10, 1958), it is now commonly considered The Twilight Zone’s first pilot. Viewers in Cincinnati did not know it, but they had entered The Twilight Zone seven years earlier than the rest of the country.

Another episode of The Storm, “The Pitch,” became a first-season Twilight Zone episode, “One for the Angels,” which starred Ed Wynn as a kindhearted peddler of trinkets who receives a visit from Mr. Death. While The Storm’s version of “The Time Element” closely resembles the Desilu Playhouse version, “The Pitch” differs significantly from its Twilight Zone counterpart. “The Pitch” involves an ineffectual sidewalk salesman, Lou, who lives with his father and his younger brother, Vinnie, who works as a bookmaker for organized crime. When Vinnie’s boss discovers that he has been skimming gambling money, Vinnie retreats to the family apartment, convinced that the next time he steps outside, his life will be in danger. Lou convinces his brother that it is safe to leave the building because the street outside is crowded with people and his boss would not risk gunning him down in front of so many witnesses. Where The Twilight Zone’s version called for Lou to perform a pitch mesmerizing enough to distract Mr. Death from his appointment to claim a young girl struck by a car, The Storm’s version requires Lou to attract and hold a crowd of potential witnesses around his brother all day and deep into the night.

The Storm initially aired every other Friday night and was billed as a mystery series. Serling’s first three scripts for the series fit roughly within that genre. Following “Keeper of the Chair” were a revised version of Serling’s old radio script, “The Air Is Free,” broadcast on July 31, 1951, and “Vertical Deep,” which partly dealt with the search for an escaped war criminal (September 25, 1951).

The Storm then began appearing every week, first on Sunday nights, then Tuesday nights, Saturday afternoons, and finally Saturday nights. Although the series had no sponsor, broadcasting an original drama using exclusively local talent was a point of pride for WKRC, so the station was content (at least temporarily) to cover the production costs. Once the series began airing weekly, Serling wrote every script. The first of these was “A Phone Call from Louie” (September 30, 1951), of which Serling later wrote, “It has absolutely nothing to recommend it other than the fact that it’s written in the English language.”16 From this point forward, The Storm was no longer limited to the “mystery” category, with Serling’s scripts falling into a wide variety of genres.

The most intriguing and historically significant lost episode of The Storm, “As Yet Untitled,” aired on April 5, 1952. This story represents Rod Serling’s first attempt to use television drama to address the issue of racial prejudice. Given the state of the medium at the time, it likely represents the first time anyone had dealt with this issue in a television drama.

“I happen to think the singular evil of our time is prejudice. It is from this evil that all other evils grow and multiply.”17 Serling said this in 1967. He believed it his whole adult life. At the height of his success, Serling’s continued attempts to dramatize this evil sparked contentious battles with sponsors, though that issue did not arise with “As Yet Untitled.”

The Storm had attracted a sponsor in November 1951, but by the time “As Yet Untitled” aired, WKRC was again footing the bill. With no sponsor to reject a script for fear that its product could be tainted by association, The Storm afforded Serling a degree of creative freedom that he did not again enjoy until he traveled to another dimension. And so, in April 1952, he ventured into an area that would have been forbidden on network television. Although the script has not been preserved in Serling’s papers, other sources provide information about its theme and plot.

Whenever Serling completed a script for The Storm, he immediately sent a copy to Blanche Gaines. On March 28, 1952, Gaines wrote to acknowledge that she had received and read his “Chinese-American story.” It was, in her opinion, “too much of a tract—and only repeated something we have been made aware of through the newspapers.” Nevertheless, she forwarded the script to Dick McDonagh, story editor for Lux Video Theatre, and on April 11 she relayed McDonagh’s reaction: “It is going to be difficult to get a network production on this one—though it is very good writing and very topical and very forceful drama.” Referring to the script specifically as “As Yet Untitled,” Gaines added, “Incidentally, I felt the same way about no network touching it on account of the subject matter. Was this one done in Cincinnati?”18

Gaines was right. No network would touch it. But “As Yet Untitled” was indeed produced in Cincinnati on April 4, 1952. TV Dial magazine described it as “the story of a young Chinese couple who buy a house in a nice section of town only to be run out because of the color of their skin.”19 This synopsis also describes the incident that inspired Serling’s story. In February 1952, a twenty-five-year-old Chinese man, Sing Sheng, placed a down payment on a home in Southwood, an all-white, middle-class neighborhood in South San Francisco. Before he could move into his new home with his pregnant wife and their two-year-old son, several of his prospective neighbors confronted him and said that his family’s presence “might lead to unpleasant incidents” and that “children might throw rocks and dump garbage” on his property if he moved in. Formerly an intelligence officer in the Chinese Nationalist army, Sheng attended college in Indiana, intending to enter diplomatic service. He met his Chinese American wife there, and they chose to remain in the United States after the 1949 communist revolution. While his adopted country was ostensibly fighting communism in Korea, Sheng refused to believe that a majority of Americans would discriminate against him. He suggested that the matter be put to a vote among Southwood residents and promised to abide by the outcome. He gambled on the open-mindedness of the average American. He lost. On February 16, 1952, 174 of the 222 attendees at an open meeting voted to bar a “non-Caucasian” family from taking up residence. Sheng’s response was so consistent with Serling’s views that he could have used it verbatim as dialogue in “As Yet Untitled”:

If that is their true feeling, then the war in Korea is being fought for nothing.… I think we are in a conflict now, not between individual nations but between Communism and Democracy. The essential assets of Democracy are equality and freedom. Out on the fighting front, whether your fellow soldier is a Chinese or a Negro or a white man, you don’t care. There are no questions asked. Now you come back to a thing like this. I can only hope the Communists don’t hear about it. It would be too good a propaganda for them.20

A few days after the vote, supporters of the Shengs’ right to live in Southwood met at a local church to “make public expression to the world” on behalf of the Shengs. Many of those who had voted in favor of racial discrimination also attended, intent on letting “the world know about our stand” and on insisting that “we owe no man an apology.” The owner of the largest house in town subsequently declared, “I do not want to continue living with a bunch of bigots,” and announced his intention to sell his house “to any person regardless of race or color, nationality or creed.”21

Sheng’s story sparked editorials across the country and became international news. On March 2, 1952, he was interviewed by journalist Edward R. Murrow on the See It Now program. Serling likely began writing “As Yet Untitled” shortly thereafter. Though he was not yet thirty years old and had sold a total of four television scripts to national network series, Serling was already intent on using drama as a “vehicle of social criticism.” He already aspired to “focus the issues of his time.”22 And he had already encountered an obstacle that he went on to confront repeatedly: in television, “very good writing” and “very forceful drama” mean nothing if the subject matter is unacceptable. And on television in the 1950s, any racial theme was unacceptable.

While Serling’s agent encouraged him to leave Cincinnati for New York, Bob Huber had a “best of both worlds” option in mind for The Storm. Throughout the run of the series, Huber and WKRC tried to sell the series to a network in the hopes that it could air nationally while continuing to be produced in Cincinnati, where production costs would be lower than in New York. On November 13, 1951, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “The Storm will be seen in New York by officials of CBS two weeks from today. The network may be interested in the show for full network showing—provided a sponsor can be found.”23

PREJUDICE:

“That is perhaps the worst thing about prejudice. The haters turn the victims into haters. You line up the two teams, who can tell them apart?”

—“A Storm in Summer,” Hallmark Hall of Fame

Some of Rod Serling’s stories addressing prejudice:

“As Yet Untitled,” The Storm

“Noon on Doomsday,” United States Steel Hour

“A Town Has Turned to Dust,” Playhouse 90

“The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” The Twilight Zone

“The Shelter,” The Twilight Zone

“I Am the Night—Color Me Black,” The Twilight Zone

“The Homecoming of Lemuel Stove,” The Loner

“Widow on the Evening Stage,” The Loner

“The Hate Syndrome,” Insight

“A Killing at Sundial,” Chrysler Theatre

“A Storm in Summer,” Hallmark Hall of Fame

“Class of ’99,” Night Gallery

Two weeks later, WKRC broadcast “Aftermath,” a boxing-themed story. To enable CBS executives to see the show, WKRC covered the considerable expense of creating a kinescope of the performance using the network’s machine in New York. The kinescope malfunctioned, however, capturing the video but garbling the audio and making the recording unusable. Still determined to pitch the series, Huber and WKRC decided to try again, this time by filming a live performance.24 The script chosen for filming was Serling’s Korean War drama, “No Gods to Serve.” It is the only surviving episode of The Storm generally available for viewing.

“No Gods to Serve” tells the story of six soldiers, including a seriously wounded army chaplain, trapped in the basement of a Korean farmhouse during a firefight. A nineteen-year-old private shoots an enemy soldier and leaves him outside to die. The chaplain argues that they bring the wounded man to the relative safety of the basement, while the other platoon members argue against taking the risk. The platoon sergeant reluctantly agrees to retrieve the enemy but discovers that he is still armed and is not as badly wounded as they had thought. The sergeant buries his bayonet in the enemy’s chest just as he fires a shot, leaving both men dead. The surviving soldiers blame the chaplain for the sergeant’s death, though forgiveness quickly follows. With the enemy closing in, the men realize that they must abandon their position, but the chaplain is too wounded to travel. Despite his urging, they refuse to leave him behind, and he ultimately convinces them that he is well enough to move. After climbing from the cellar, the other soldiers realize that the chaplain is still below and never had any intention of leaving. From a safe distance, they watch as the enemy swarm. Hearing the sound of gunfire, they realize that the chaplain has sacrificed his life for theirs.

Rod Serling, publicity photo, ca. 1953.

Prior to filming “No Gods to Serve,” WKRC prepared for the possibility that CBS would buy the series by offering Serling a contract that would pay him three hundred dollars per week to continue writing the show. Gaines, opposed to anything that might keep her client in Cincinnati, advised him against taking this offer. Serling never had to make a decision: CBS chose not to buy the series. On April 19, 1952, the Cincinnati Enquirer announced that The Storm had been canceled.25 One week later, the Enquirer’s television writer, John Caldwell, confirmed that that night’s episode, “A Machine to Answer the Question,” would be the series’s final broadcast. Caldwell, who had been one of the series’s biggest supporters, lamented that the machine of the title “can’t answer … why The Storm has to be canceled.”26

“A Machine to Answer the Question” concluded the series with a tantalizing suggestion of things to come. Serling’s genre-spanning science fiction mystery involved a spate of worldwide UFO sightings, the apparent murder-suicide of two prominent physicists, and an impending attack by spaceships sent from Mars. When the same story was later produced on radio, it began with an evocative narration:

This is the universe. A sky crowded with billions of tiny pinpoints of light—each like the dot in a question mark. For in these star-packed heavens is the riddle of existence. That twilight land of the unknown where imagination must replace knowledge; hypothesis takes the place of fact. Man’s small mind can only project so far … then merely question. What’s needed is a device to explain the mystery—to probe the void … a machine to answer the question!

On October 2, 1959, Serling introduced his “twilight land” on a much grander scale.

* The low priority that WLW afforded dramatic programming is indicated by the fact that a little more than a year after Serling resigned from the station, WLW produced a television script that he had written as a freelancer. “Three Stories in Search of an Ending” was advertised as “A Drama Written by Rod Serling, Featuring an All-Star Cast.” The show was fifteen minutes long. With an average of five minutes per story, it’s no wonder they were in search of an ending—WLW hadn’t allowed enough time to include one!