Live from Television City in Hollywood

PLAYHOUSE 90

Rod Serling had little time to lick his wounds from the “Noon on Doomsday” experience before he was enlisted to work on what was being groomed to be the crown jewel of the Tiffany network: Playhouse 90, television’s first ninety-minute weekly live drama. CBS, under the stewardship of chairman William S. Paley and vice president Hubbell Robinson, allotted this risky venture an initial budget of $100,000 per episode, but the network routinely spent as much as $150,000 or more. Its generous budget and the fact that it was performed and broadcast not from New York but from Hollywood enabled Playhouse 90 to assemble casts that rivaled those of major motion pictures. Producer Martin Manulis, who had previously worked with Serling on Suspense and Climax!, recruited Serling to serve as primary writer.

For Serling and the show’s other writers, Playhouse 90 provided an unprecedented degree of creative freedom. Its length alone offered opportunities to devise deeper characters and more complex plots. Moreover, Paley and Robinson explicitly treated Playhouse 90 as a prestige piece. Ratings and profitability mattered, of course, but quality was at least as important. “Invariably, Playhouse 90 had a sizable portion of the audience, and even if in arithmetic terms it didn’t have, it was nonetheless a talked-about show,” Serling later said. “It was television coming of age. It was proscenium drama being [performed] in front of a camera. These were substantial pieces, pieces of substance and points of view, and even when they failed, they failed with a sense of class, of aplomb.”1

The series ultimately produced ten of Serling’s scripts, and New York Times critic Jack Gould labeled Serling and Playhouse 90 “perhaps the most consistently fruitful partnership in television.”2 A little more than a month before its debut, Manulis joked that “Mr. Paley’s most important toy” would soon be launched by “The Rod Serling Festival.”3 Many critics, however, saw this launch as a misfire.

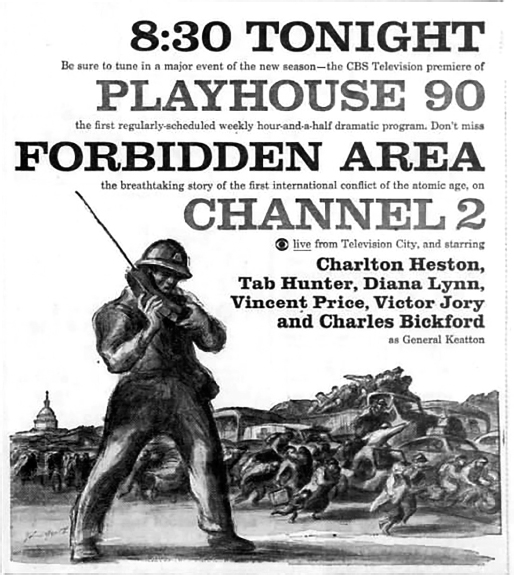

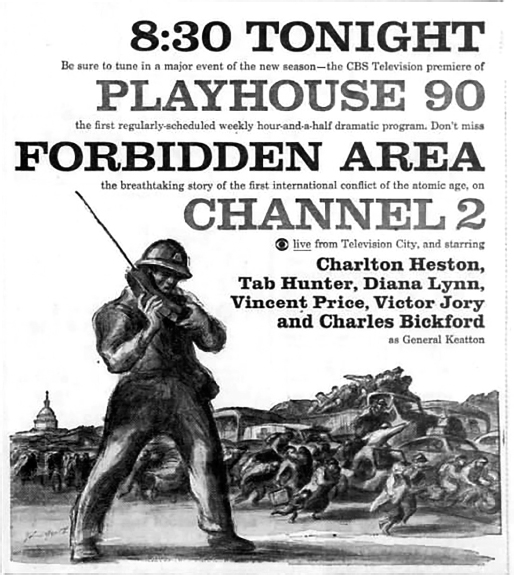

On October 4, 1956, Playhouse 90 debuted with “Forbidden Area,” a Cold War thriller starring Vincent Price, Charlton Heston, and Tab Hunter that Serling adapted from a novel by Pat Frank. Hunter played a Russian spy who infiltrates the US Air Force to sabotage a newly designed aircraft, intending to force the fleet to be temporarily grounded and leave the United States vulnerable to a Russian air attack.

Several critics found its plot to be preposterous. Gould described it as “a war drama that ran the gamut of hokum.”4 United Press critic Charles Mercer, however, dissented: “It would be easy to adopt a highbrow view that ‘Forbidden Area’… was an implausible and over-inflated melodrama. Several usually astute critics have said that it was. But I found it first-rate, absorbing television entertainment.”5 And the International News Service’s Jack O’Brian called it “the finest serious drama we’ve seen so far on television.”6

Nine of Serling’s Playhouse 90 scripts were produced between October 1956 and May 1959. His final script to be produced, “In the Presence of Mine Enemies,” was broadcast one year after that, though it had been written much earlier. In total, Serling wrote the equivalent of ten feature-length scripts in about three years. Rebutting the frequent charge that Serling tended to sacrifice quality for speed, virtually all of them garnered some degree of critical acclaim, with both “Requiem for a Heavyweight” and “The Comedian” earning Emmy Awards. His scripts for “A Town Has Turned to Dust,” “The Dark Side of the Earth,” “The Velvet Alley,” and “In the Presence of Mine Enemies” earned various awards and nominations as well.

But the series also entangled Serling in several controversies, most notably those involving “A Town Has Turned to Dust” (see chapter 10) and “In the Presence of Mine Enemies” (see chapter 13). Serling was even drawn into a controversy sparked by a Playhouse 90 script that he hadn’t even written.

On November 21, 1957, Playhouse 90 broadcast “The Troublemakers,” which was adapted by George Bellak from his original play. The story, inspired by an actual incident, involved a college student beaten to death by a group of fellow students after writing inflammatory articles in the campus newspaper. A little more than a week before the performance, director John Frankenheimer called on Serling to rewrite portions of Bellak’s script. Barely a day after Serling began his rewrite, Manulis called Frankenheimer with a warning that Playhouse 90’s five sponsors were threatening to withdraw sponsorship. The reason: forty-five Roman Catholic newspapers and magazines had published a story claiming that the 1954 Off-Broadway production of The Troublemakers had argued “for soft handling of suspected communists.” Network officials panicked and requested a raft of edits. Frankenheimer, Manulis, and the entire production crew endured days of story conferences, and ten lines of dialogue ultimately were changed to appease sponsors.7

Serling wrote both the series’s debut and its final offering, which aired on May 18, 1960. By that point, the era of live drama had officially ended, and Serling had already transitioned to a filmed science-fiction series that overshadowed everything he wrote for Playhouse 90 or anywhere else.