Promotional poster for the US theatrical release of Requiem for a Heavyweight.

A Ninety-Minute Knockout

“REQUIEM FOR A HEAVYWEIGHT”

If I’m a household name, it’s a fortuitous event, really singularly undeserved.

—ROD SERLING, 1960

I’ve won five of the Emmys, but of those five, in good conscience and with great candor, I must say that I think I deserved two of them.

—ROD SERLING, 1960

There was not one redeeming feature in [Saddle the Wind]. I gave better dialogue to the horses than the actors.

—ROD SERLING, 1961

One year after [The Twilight Zone] goes off the air, they’ll never remember who I am.

—ROD SERLING, 1963

Twelve years ago [The Twilight Zone’s “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street”] had great significance, and now suddenly I don’t know what the hell happened to it.

—ROD SERLING, 1971

[The Twilight Zone’s “Walking Distance”] never works for me now. Every time I see it, I die.… The writing was really second rate.

—ROD SERLING, 1975

You judge good writing by its lasting qualities … and nothing I’ve written in my life, and that spans 24 years of professional writing, will ever be remembered 100 years hence.

—ROD SERLING, 1971

The Angry Young Man is now 47, and what has he accomplished? Not a hell of a lot.

—ROD SERLING, 1972

When I look back over thirty years of professional writing, I’m hard pressed to come up with anything that’s important. Some things are literate, some things are interesting, some things are classy, but very damn little is important.

—ROD SERLING, 1975

To say that Rod Serling was his own harshest critic is like saying Joe Louis was a pretty good fighter. In the words of his longtime agent, Blanche Gaines, Serling could “run himself down with some assurance.” As director John Frankenheimer more pointedly put it, “Rod could have been a combination of Albert Schweitzer and Ernest Hemingway and still it would not have been enough. Rod never gave himself a break.”1 Serling recognized his tendency to be overly harsh on himself long before he became a professional writer. When applying to Antioch College in 1946, he bluntly declared, “An inferiority complex when it comes to my own talents is at this point my chief weakness … consciousness of my shortcomings [is] almost an obsession.”2

The overwhelming critical success of “Patterns” did little to ameliorate these hypercritical tendencies and in some ways intensified them. With success Serling felt the need to prove that this success was no fluke, a task made significantly more difficult by an incessant inner voice whispering that that’s exactly what it was. “Patterns wasn’t my only success,” he wrote, “but it evolved as the single standard by which I was judged. It was a point of comparison. I now had to fight myself or at least something I’d done. I had something to prove, first to others and then to myself. I had to prove that Patterns wasn’t all I had.… As it turned out, it took a long time to prove. Almost two years.”3

By Serling’s accounts, that period—the twenty-one months between the first broadcast of “Patterns” and the debut of Requiem for a Heavyweight on Playhouse 90—apparently felt like twenty years, during which time he spent every moment of every day trying to hit a home run as majestic as “Patterns” and instead striking out every time. As he recalled, “The first reviews of the shows after ‘Patterns’ were charitable … but after a time, when the comparisons [to “Patterns”] became more obviously negative, the needle was unsheathed. It got longer, it probed deeper, and I began to bleed.”4

Serling’s relationship to “Patterns” soon followed a common literary pattern: the writer began to resent his most popular creation. In 1958, he told the Cincinnati Enquirer,

Patterns was a well-written piece, I guess, but I’m sick to my gut of hearing about it. You’re always judged by your greatest success. It even seems you’re remembered for little else. It’s always around to haunt you. Sometimes when I’m interviewed people say, “And here is the author of ‘Patterns’ and … well, here’s Rod Serling.” They can’t remember anything else I wrote. If I thought about that play enough, I might end up committing suicide in the belief that I could never top it. So I just don’t like to hear about it anymore.5

In his first book, 1957’s Patterns, Serling offered a tough but fair assessment of his work, with substantial criticism as well as some of the rare instances in which he complimented himself. “I thought The Rack was better written than Patterns,” he wrote. “I thought Noon on Doomsday had more innate power. I thought The Strike … had more universality and more appeal. But I was a minority of one.”6

Even when Serling held a positive opinion of something he had written, this was not enough to satisfy his insecurity. He needed to be more than a minority of one. With “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” he received the universal validation that he needed. “Requiem” was broadcast on October 11, 1956, as the second episode of Playhouse 90 and the first original ninety-minute play written for television. The play begins with the final bell of a heavyweight fight between Jake Gibbons and Harlan “Mountain” McClintock. Gibbons jogs up the runway, accepting pats on the back from glad-handers and hangers-on, looking like he’s just completed nothing more strenuous than a jog around the arena. He and his crew clear out and Serling’s hero appears: McClintock, played by Jack Palance, battered, eyes swollen shut, and being carried by his manager, Maish (Keenan Wynn), and his trainer, Army (Ed Wynn). This has been Mountain’s 111th and final fight. Although he had risen as high as fifth in the heavyweight division, fourteen years of beatings has taken its toll. A doctor examines him laid out on a training table like a slab of meat and declares that the boxing commission will never again sanction him to fight. With one terse pronouncement, McClintock is thrown into an existential limbo. Boxing is all he knows; a boxer is the only thing he knows how to be.

At a bar soon thereafter, he raises a toast to himself: “Here’s to Mountain McClintock. He never was no good, but he never took a dive.” Having maintained his integrity is the only victory he has left to savor. And his integrity and his dignity are now the only things he has left to lose.

Unbeknownst to McClintock, his trusted manager has been wagering against him—and losing, thanks to McClintock’s ability to stay on his feet for more rounds than Maish ever thinks is possible. Maish is now in serious debt to serious people. To square his debts, he intends to turn Mountain into a professional wrestler. When McClintock protests, “I don’t know how to wrestle,” Maish explains that wrestling is phony: “One night you win, the next night the other guy wins.” To McClintock, this is the equivalent of taking a dive. To add insult to this injury, Maish intends to dress McClintock in a ridiculous costume and bill him as the Mountaineer. Mountain can’t bring himself to surrender his dignity. With the encouragement of his trainer and a kindly social worker (Grace Carney, played by Kim Hunter), he gets on a train to return home to Kennesaw, Tennessee, but he’ll soon be back to take a job that Carney has arranged, working with children at a summer camp. While on the train he meets a young boy and gives him a few pointers about boxing. Mountain’s skill at communicating with the boy reveals that he may have some untapped talents after all.

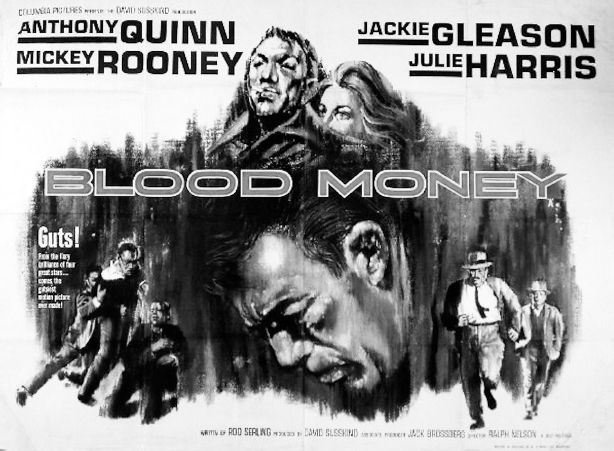

Promotional poster for the US theatrical release of Requiem for a Heavyweight.

Both critics and the public lavished praise on “Requiem.” One day after the performance, actress Jane Wyman, at the time the host of Fireside Theatre for the rival NBC network, sent Serling a telegram: “All of us here feel that Requiem for a Heavyweight should be retitled ‘Hosanna for Rod Sterling [sic].’ There aren’t enough adjectives even in Hollywood to tell you how great it was.”7 Serling acknowledged the critical praise but downplayed its significance: “Requiem probably won’t win an Emmy. And it may cease to be even a memory in a few weeks. But I can tell you that it was much needed in this boy’s career. It was like going to the bathroom and cleansing myself of an awful gut obstruction known as PATTERNS.”8 As was his habit, Serling was selling himself short: “Requiem” virtually swept the Emmy Awards, winning the award for Best Single Program and individual honors for Serling, Palance, and director Ralph W. Nelson.

Promotional poster for the UK theatrical release of Blood Money (alternate title of Requiem for a Heavyweight).

While Serling acknowledged that the climax of “Patterns” was not his idea and that the play had evolved “a little more collaboratively than most,” “Requiem” was 100 percent Serling’s baby, and its success was much more gratifying. He later reflected, “There are certain pieces that you write that a piece of the flesh goes with it. And in my case, ‘Requiem’ was probably the one.”9 Despite his penchant for self-criticism, Serling never uttered a negative word about “Requiem for a Heavyweight.”

Less than six months after its performance on Playhouse 90, the play was performed in the United Kingdom on the BBC’s Sunday Night Theatre. Palance was initially expected to reprise his role, but he became unavailable, forcing the producers to replace him with an unknown Scottish actor making his live television debut. His name was Sean Connery. The BBC production received similarly favorable reviews.

After several years of attempts to adapt “Requiem” for the Broadway stage, Serling instead adapted it into a feature film, which was released in 1962. This version is grittier, more realistically staged, and ends on a darker note, with Mountain deciding to swallow his pride and don the demeaning wrestling costume literally to save Maish’s life. For the feature film, Anthony Quinn replaced Palance as the renamed Louis “Mountain” Rivera. Jackie Gleason replaced Keenan Wynn as Maish, and Mickey Rooney took over as Army. Serling’s affection for the television play did not extend to the feature film: he described it as “not a very good picture … badly directed, poorly performed except from Mickey Rooney and Gleason. I thought Tony Quinn was not right for it…. Jack Palance gave it considerably more dignity in the live television version than Tony Quinn did.”10

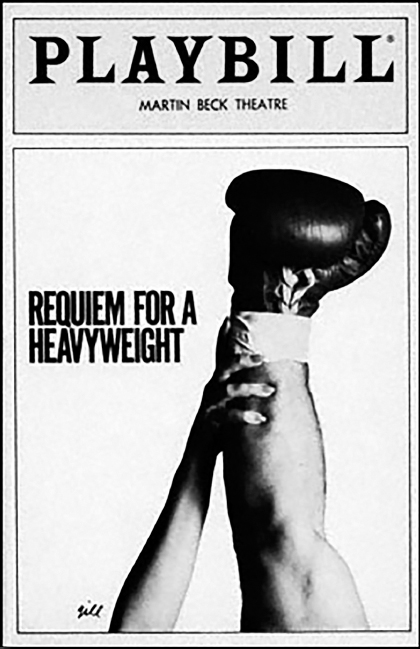

Requiem for a Heavyweight, starring John Lithgow, opened and closed on Broadway in less than a week.

To become a legitimate playwright was Rod Serling’s greatest unfulfilled dream. Nearly ten years after his death, “Requiem for a Heavyweight” finally made it to Broadway, debuting on March 7, 1985, at the Martin Beck Theatre. The production starred John Lithgow, who earned rave reviews and a Tony nomination for his portrayal of Mountain McClintock. The play itself, however, was critically panned and closed after four performances.