It’s about Time

DESILU PLAYHOUSE’S “THE TIME ELEMENT”

When Rod Serling sent a copy of “The Time Element” to his agent, Blanche Gaines, in 1951, he referred to it as the best fantasy he had yet written. Gaines could not sell it. On network television, fantasy was unwelcome. “The Time Element” was produced as an episode of The Storm, seen only in the Cincinnati area, and Serling’s script was then returned to a drawer to gather dust. Three years later, Serling produced “The Time Element” as an episode of a radio series, It Happens to You, but did not pitch the script to television.

By 1957, however, Serling’s star had risen and he had been given the green light to propose the concept that eventually became The Twilight Zone. He unearthed “The Time Element” and submitted an expanded version of the script to CBS under the title “Twilight Zone—The Time Element.” The network bought the script but promptly rejected it as a series pilot. Fantasy remained verboten on prime-time television.

Bert Granet, producer of Westinghouse’s Desilu Playhouse, however, bought the script with the backing of the show’s host, Desi Arnaz. Predictably, however, the sponsor balked at the story, primarily as a consequence of its “unfinished” ending: “They wanted neat bows at the end where each story wrapped up,” Granet said.1 Granet (and Arnaz) ultimately won the battle to produce Serling’s unconventional script only after Granet promised never again to suggest this type of story for the series. He also promised CBS that the title Twilight Zone would not appear in any of Desilu’s promotional materials, since the network was still considering Serling’s series proposal. And so although The Twilight Zone never appeared on-screen, this episode of Desilu Playhouse is, for practical purposes, The Twilight Zone’s true pilot.

CBS

“The Time Element”

November 10, 1958, 60 min.

Alternate titles/productions/publications:

1. Produced on The Storm, December 11, 1951

2. Produced on It Happens to You (NBC radio), August 10, 1954

3. Script in Albarella, As Timeless as Infinity, vol. 1

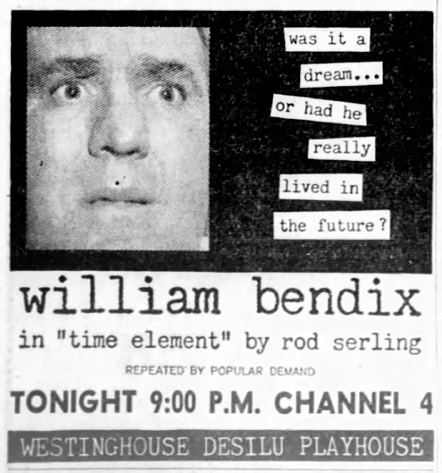

Produced by Bert Granet; directed by Allen Reisner

Cast: William Bendix; Martin Balsam; Darryl Hickman; Jesse White; Carolyn Kearney; Jesslyn Fax; Alan Baxter; Bartlett Robinson; Don Keefer; Joe DeRita; Paul Bryar

Synopsis:

Once upon a time there was a psychiatrist named Arnold Gillespie and a patient whose name was Peter Jenson. Mr. Jenson walked into the office nine minutes ago. It is eleven o’clock, Saturday morning, October 5, 1958. It is perhaps chronologically trite to be so specific about the hour and the date … but involved in this story is … a time element.

Pete Jenson (William Bendix) has been having a recurring dream that has disturbed him so deeply that he has sought treatment from a psychiatrist, Dr. Gillespie (Martin Balsam). The agitated man Jenson explains that in this dream he awakens with a terrible hangover in an unfamiliar hotel room in Honolulu. He is told that the date is December 6, but he is certain that he went to sleep in October and in New York. He figures he must have gone on the worst drunken bender of all time to lose track of two months of time and to end up five thousand miles away from where he last remembers having been. But soon enough he discovers that he has traveled much more than five thousand miles. The date is December 6, 1941. He has traveled backward in time almost seventeen years.

The dream has proceeded a little farther each night for a week. In the dream, he makes friends with a newlywed couple, Mr. and Mrs. Janoski. Ensign Janoski serves on the USS Arizona. Jenson recalls the name of that ship and knows that it will be sunk when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor the next morning. He tries to warn Janoski and then the press, but no one believes him. The worst part of the entire experience, he tells Gillespie, is not the feeling that no one will believe him. It’s his conviction that this is not a dream. He believes he has been truly traveling backward in time.

Gillespie offers logical, rational explanations for why Jenson believes in the reality of his dream, but Jenson counters with examples of things that cannot be explained unless the dream were real. How is Jenson so intimately familiar with Hawaii when he has never been there? And how can Gillespie explain the fact that when he tracked down Ensign Janoski’s mother by phone, she confirmed that her son and his wife were killed during the attack on Pearl Harbor?

Jenson and Gillespie talk for hours, and Jenson eventually falls asleep on the doctor’s couch. His dream resumes. His time has run out. As he watches out his hotel room window, incoming Japanese planes fly overhead. As the attack begins, he cries, “I told you! Why wouldn’t anyone believe me?” over and over again.

Back in his office, Dr. Gillespie finds that he’s alone. He rubs his eyes and looks around, seemingly unsure how he has gotten there. There is no sign that he has seen any patients today. He goes to a local bar for a drink and spies a familiar face in a picture behind the bar. He asks the bartender who the man in the picture is. “That’s Pete Jenson,” he says. “He used to tend bar here.” When Gillespie asks where Jenson is now, the bartender answers, “He died at Pearl Harbor.”

It is October 5, 1958, Saturday, twelve P.M., if anyone is remotely interested in the element of time!

Notes: The original draft of “The Time Element,” which was produced on The Storm on December 11, 1951, proceeds from the same premise as this version with a few variations. In The Storm version, the main character, Paul Ramsey is found wandering in San Francisco in December 1941 with no memory of the preceding two weeks. Ten years later, he begins to have a recurring dream in which he finds himself at Pearl Harbor just before the attack. The dreams are so vivid that he wonders whether he was actually there during those missing days in 1941 and whether he is actually traveling back to those days, given a second chance to warn people of what is coming. Just as in the Desilu version, Ramsey turns out to have been killed at Pearl Harbor, leaving the psychiatrist to wonder how he can recall treating Ramsey in 1951.

Desi Arnaz’s support for “The Time Element” makes him one of the unsung heroes in The Twilight Zone’s history. Lucie Arnaz (the daughter of Arnaz and Lucille Ball) recalled that The Twilight Zone became one of her father’s (and her own) favorite shows, although she had no knowledge of his connection to the series until decades later. “I watched it religiously,” she said. “I watched every rerun—I became like a fanatic about it. After my parents divorced I spent weekends and summers at my dad’s—he watched it with me a million times. He never once said ‘Hey, you know if it wasn’t for me …’ He never took credit.”2

Though Desilu and Desi Arnaz were instrumental in paving the way for The Twilight Zone as a series, Desilu later prevented what could have been the first Twilight Zone feature film. In late 1961, Serling and his agents were in discussions with Kirk Douglas to star in a feature film version of “The Time Element.” Desilu, however, had first-refusal rights to any “Time Element” motion picture. Apparently believing that Desilu was unqualified to handle a major motion picture, Serling’s agents asked Desilu to waive its right, but Desilu refused, implying that it might exercise the right to produce the film if given the chance. On January 16, 1962, Bernard Weitzman of Desilu wrote to Serling’s agents, “If Rod’s people … proceed to do the motion picture without first offering us the deal, then he assumes the risk of any subsequent consequences.”3 There is no evidence that Serling followed through with any further proposal for a “Time Element” motion picture, either with Desilu or anywhere else.

As televised, “The Time Element” generated more positive viewer mail than any other show that Desilu Playhouse had produced that year. It also won favorable reviews from critics, including a rave from Jack Gould of the New York Times, who wrote, “The humor and sincerity of Mr. Serling’s dialogue made ‘The Time Element’ consistently arresting. Mr. Serling had his troubles in Hollywood over script censorship, but where other dramatists either capitulate or retire, he manages to achieve a great deal through the subtlety of his approach. What he might do with no shackles could be most exciting.”4

The shackles were about to come off.