Organizational Circulatory Systems

An Inquiry

OVER THE PAST 30 years, the idea has been floated again and again that organizations are “living systems:” they aren’t mechanistic and shouldn’t be thought of as machines. Among the writers who have put this idea forward are Gareth Morgan (in Images of Organizations), Arie de Geus (in The Living Company), Peter Senge (in The Fifth Discipline), and Eric Trist (in his various papers). And there’s good reason to believe they’re right. After all, as anyone who has ever tried to intervene in an organization can tell you, they don’t react as machines would when you try to fix them.

When approached with change, in other words, they do not respond like clocks, automobiles, engines, telephones, or even computers. They do not either start working better or stop working at all. Instead, they respond like animals, plants, families, and communities. They shift course and react in unexpected ways, often rejecting the measures and approaches that you thought would be most helpful.

But if the idea that organizations are living systems makes sense, there’s far less of a complete understanding about how to translate that into effective interventions. This is one reason why Elliot Jaques was right when he said, “Management is in the same state today that the natural sciences were in before the discovery of the circulation of the blood.” The fields of organizational design and effectiveness, to say nothing of organization development, are full of practitioners who apply “best practices” to fix organizational problems in the same way that barber-surgeons once applied leeches. They base their interventions on a great deal of practical experience, but they’ve unconsciously learned to differentiate those cases where the patient lived (“proof that my method works”) from those cases where the patient died (“those just aren’t significant examples.”) And while there’s a lot of organizational theory to draw on, most of it remains far less robust than, say, the theory of the circulation of the blood. To say nothing of an understanding of germs or DNA.

None of this is surprising. After all, large managerial organizations, separate from the state or the church, have only existed since the mid-19th century. They began with the railroad and the telegraph. We have only had 175 years or so to begin to understand them. And it took a long time to recognize that they are living systems. But if they are living systems, where would we look first to learn how they work?

Maybe the answer is to look at circulatory systems. Some of the most interesting and accessible writing (at least to a lay person like myself) about the human body has to do with circulatory systems. For example, Sherwin Nuland, the Yale University-based surgeon and writer, used the following passage to explain the uncanny responses of human physiology in his book The Wisdom of the Body:

To coordinate all of the instabilities in all of the cells [of the human body] requires that the far-flung parts of an organism be in constant communication with one another, over long-distances as well as locally…. This is accomplished by messages sent via nerves, in the form of electrical energy we call impulses; via the bloodstream, in the form of the chemicals we call hormones; and—to nearby groups of cells—via the specialized substances we call local signaling molecules. As each of these methods of communication was discovered, researchers … came to recognize the inherent wisdom of the body.

Might the same be true of circulatory systems in the organizational body? For the past few years, ever since my book Who Really Matters was published, I’ve begun to think it’s true. Indeed, there are probably dozens of circulatory systems through which organizations get their work done. Some of them are machinelike in many respects: Information Technology systems or supply chains. But all of them are living in some way—even the architecture of an office building is, in some vernacular way, alive.

I’ve been attracted to four circulatory systems in particular. In the rest of this article, I’d like to express some very preliminary ideas about these four circulatory systems, how they work, and the implications for intervention. I do this not as an OD practitioner (indeed, my consulting experience is very limited) but as a historian, writer and editor whose subject is management. I’d like nothing better than to be corrected and to adjust my perceptions based on actual empirical evidence—or based on more robust theory. And I’d be grateful to find out that, like Robinson Crusoe, I’ve simply been ignorant of others’ explorations.

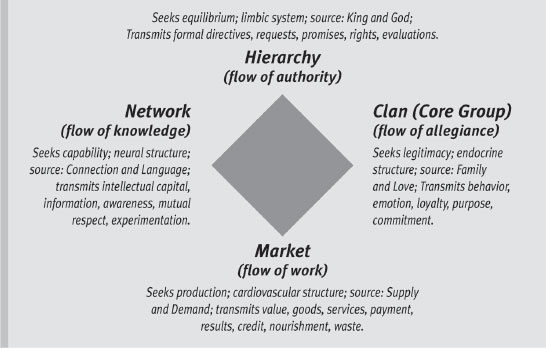

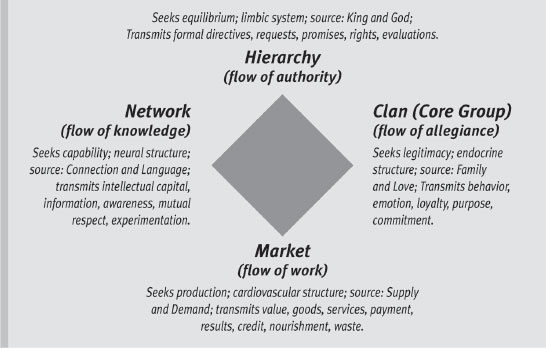

The four circulatory systems that attract me have certainly been written about elsewhere. They are the Market, the Hierarchy, the Network, and the Clan (Figure 35.1). But they have not typically been described as webs through which different types of information and other things travel. And that description may be helpful in making sense of them.

The Hierarchy

We think of hierarchies as controlling mechanisms, but actually they are circulatory systems for aggregation. They are the means through which an organization scales itself up without losing equilibrium. Alfred D. Chandler, in his studies of railroad enterprises as the first managerial organizations, noted that the most distinctive feature of them was their hierarchies. Owners needed to make sure that there were people and systems in place to manage the various far-flung parts of a railroad line, with similar systems for scheduling trains, charging fees, and keeping track of profits. Otherwise, the whole system would (literally) crash.

The hierarchy is perhaps equivalent to the limbic system of a living mammal. It is not a sophisticated conveyance, but without it, movement and growth would cease. And it resonates with primal attitudes about King, God, and authority. When the system is under stress, communication reverts to the hierarchy.

Our best theorist about hierarchies is in fact the late Elliott Jaques, who proposed that some hierarchies were “requisite”—that is, well-suited to the nature of human beings who worked within them. Jaques’ proffered that hierarchical design had some qualities in common with golden mean-based designs for buildings. A good hierarchy places people at a level of authority consistent with the cognitive capabilities, and it manages them so that they rise gradually through the system as their capabilities increase.

What travels well through a hierarchy? Preliminary observations suggest that the hierarchy carries anything that can be aggregated easily: estimates, statements of completion, evaluations, decision rights, categorization, statements of acceptance or decline, and statistical data. Fernando Flores and Terry Winograd, when they established their idea of “conversation for action,” may have been actually naming types of speech that flow easily through a hierarchy: requests, promises, offers, and so on. All of these can be added up and tracked without much effort.

FIGURE 35.1 Organizational Circulatory Systems

But some things don’t travel well through a hierarchy. In my experience, these include stories, excuses, analogies, trust, open inquiry, and knowledge. These types of in-depth observations and attitudes simply can’t be aggregated; they depend too much on personal contact. Therefore, the hierarchy is never the sole way to govern an enterprise; and most managers learn not to rely on this system for their communications.

The Market

Back in the 1980s, W. Edwards Deming and others wrote about seeing the “organization as a system:” or as Rummler and Brache put it, managing the “white spaces in the organization chart.” Like Eric Trist and many others, they were concerned about the actual flow of work and knowledge about work through the organization: goods, services, throughput, money, and anything tangible that ultimately reached a customer. Indeed, some of the most effective organizational work of the past 50 years, from the quality movement to sociotechnical systems to reengineering (when it worked) to lean production has all been interventions in the domain of processes and workflow. People at every step of a good lean process are trained to observe, regulate, and contribute to better flow of goods and services according to the needs of the people who will ultimately use them.

It turns out that at every stage of an organization’s work flow, there is an implicit market. There is a supplier, and a receiver, and always an implicit price for what is delivered. This is true at every stage of an assembly line, for instance—and it is also true for staff services. Every service delivered requires a charge code, and there is always a prevailing view of whether or not the service has been worth the price.

For better or worse, these implicit market transactions are not always allowed to be visible; they are often overridden by hierarchical or other considerations. But those companies that let them be freely visible tend to prosper. Thus, Caterpillar thrived by making its “internal markets” more explicit in the late 1980s, and Springfield Remanufacturing Corporation prospered by opening up its financial information in a process called “the great game of business.” I’ve come to regard most process design and quality efforts as attempts to make the market-based circulatory system flow more smoothly and clearly by enlisting the supply-and-demand dynamics at every point where one person’s work is passed over to another.

What flows through a market (or process) circulatory system easily? Anything that can be traded. Economists Paul Milgram and John Roberts have noted that a transaction-based system automatically tends toward coordination, and the same is true of a work flow in a large organization. Like a human digestive and circulatory system, there tends to be the buildup of blockages over time, and every once in a while it’s helpful to try to remove the cholesterol. (It’s even more helpful to keep exercising regularly to clear way for better throughput.)

If that’s true, then some things would flow through this system more easily than others It would carry goods and services, contracts, statements of worth (prices), bids and trades, allocations, and efficiencies. It would have a harder time with secrets, objects of ambiguous value, emotionally charged information, controls, commands, and loyalty. After all, a price is a price, no matter who’s on the other side of the transaction. It’s no coincidence that the popularity of lean production has risen at the same time that the popularity of vertical integration has fallen. An enterprise which owns its suppliers and retailers is congenitally prone to hardening of the workflow arteries.

The Network

Our understanding of the value of networks has dramatically increased since the 1970s, when Stanford University professor Mark Granovetter began to research the “strength of weak ties.” Since then, many people have applied mathematical analysis to contact among people, particularly in such measurable forms as phone and email contact. It turns out to matter much less what people talk about than simply who is talking to whom. In an organization, as the eminent network researcher Karen Stephenson has found, there are three basic roles that people fulfill, that pop up again and again in the mathematical analyses:

• Hubs—people who regularly communicate with a lot of other people, and who thus naturally act as central nodes for the flow of information;

• Gatekeepers—people who provide the only links into a sub-section of the organization or a body of knowledge, and thus control the flow of relevant informal information in that domain;

• Pulsetakers—people who are relied upon for their ability to offer perspective on the organization and its direction, and who thus maintain connections to a significant and select group of others.

One can create major changes in an organization’s effectiveness by aligning and moving people in ways that shift habitual connections for these three key roles. The network thus becomes an equivalent to the neural network of a living mammal. What starts off as informal chatter becomes habituated, deep channels of regular communication. These in turn are the channels through which the knowledge of the organization passes. People learn how to do their work, how to advance in the company, and how to build knowledge through these types of channels. They also learn whom to trust; indeed, Karen Stephenson’s book on this subject, forthcoming this year, is called A Quantum Theory of Trust.

All of these circulatory systems carry information, but what sorts of information does this particular circulatory system carry? Anything unstructured. Network typology depends not on the agenda of the meeting, but on who is in the meeting and how free they feel to talk. Information, ideas, gossip, news, light observations, knowledge and learning, working advice, collaboration all flow easily. It is more difficult to exchange emotionally fraught information, issues of depth, difficult conversations, commitments, or absolute truth; after all, these networks represent the strength of weak ties. These are the networks of acquaintanceship, not deep friendship, and they get their power more from their breadth and speed than from their depth.

The Clan

For depth, we turn to the clan. Like a community or family, the clan structure of an organization is primarily cognitive. What matters is not the actual relationships or actual people, but the images that each individual carries in his or her mind about the other people of the system. Instead of the images of mother, father, grandfather, child, or sibling, each with its emotional punch, there are images of boss. Subordinate. Peer. CEO. Customer. And rival.

In Who Really Matters, I suggested that in every organization there is some core group of key people, not exactly the same as the hierarchy. Every decision maker in the organization, from top to bottom, carries in his or her mind a mental image of that core group. Because life is short and many decisions are complex, we tend to take the cognitive shortcut of asking ourselves, “What would so-and-so think of this?” Or of saying to ourselves, “I don’t want to walk into so-and-so’s office and say this is not going to happen.” The core group for each of us individually is made up of the “so-and-sos” in each of our minds. And the core group of the organization, always shifting and in motion, is made up of the amalgamated so-and-sos of everyone in the organization, weighted by the power of each person’s decisions.

In other words: Enough people, enough of the time, make enough decisions based upon core group perceptions that this determines the direction of the organization more than any single factor. The core group doesn’t dominate all the time; but it dominates enough. And because it dominates so much, no organization will go anywhere unless the core group is perceived to endorse that direction.

That’s why “walking the talk” is so important. It doesn’t matter what the CEO really thinks. It matters what he or she is perceived to think. And if the CEO changes an attitude, it will take a while for the organization to catch up. Resistance to change occurs not because people fear change, but because they fear the consequences of contradicting the perceived priorities of the Core Group. The same resistance occurs in families, where people fear contradicting the perceived priorities of the most powerful members of the family.

The core group might range in number from one person to thousands. (The larger the core group, the greater the capabilities of the organization need to be.) Its members are not necessarily people in authority (though they often are.) Some, like the gatekeepers of the network structure, are “bottlenecks” to a key part of the enterprise (a division, a function, a product, a labor union, a supply chain element…) Some are people known for speaking with integrity or influence. Some are representatives of a key constituency. Some organizations have one stable core group; others have many core groups in constant flux. Some core groups are good for their organizations; others are highly dysfunctional. But there is no such thing as an organization without a core group Moreover, behind every great organization, there’s a great Core Group…. And behind every organization in trouble, there’s a Core Group in crisis.

The clan (or core group) structure is like the endocrine system of an organization. If you want to change an individual person in a hurry, give them a drug. Similarly, if you want to change an organization, make a sudden and dramatic change in the Core Group. But be careful of overdoses. For what travels through a core group structure easily is emotionally charged information: legitimacy, pride, shame, misunderstanding, and loyalty. What travels with difficulty are reliable news, transactions, anonymity, and commands.

Putting It All Together

Or so it seems at first glance. For I’d be the first to admit that none of this is definitive. And the empirical evidence on which it is based is spotty. At the same time, the ideas resonate enough that challenges tend to focus on details. Few people question the premise that organizations are alive, that circulatory systems are the means by which they stay alive, and that different circulatory systems respond to different types of interventions.

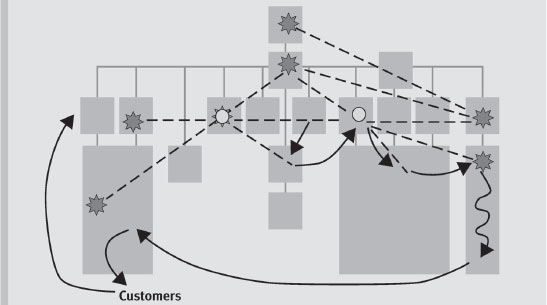

Consider, for instance, two individuals shown as circles in the organization chart in Figure 35.2.

The light grey boxes and dark grey lines represent the hierarchy. The black solid arrows show the flow of work through the market. The black dashed lines show communications channels for the network. And the stars represent people in the core group.

The circle on the left depicts someone relatively high in the hierarchy, well connected in the network, solid in the core group—and relatively far removed from the flow of work or the market. This is a bureaucrat. An organization can only afford to keep a limited number of such people, or it will go bankrupt.

Meanwhile, three boxes to the right is an individual equally high in the hierarchy, thoroughly immersed in the network, crucial to the market’s flow of work, but with no core group status. This individual is heading for burn-out. He or she may well be crucial to the organization’s survival, but will probably flee before there is a chance to find out.

There is much to learn about all four of these organizational circulatory systems, and about others as well. The stakes could not be higher, because most of the effective change that people make in the world happens in (and through) organizations. The more effective we are as intervenors, the better our world becomes. And in the end, it may be our awareness of circulatory systems—and how we fit into them—that makes us effective as intervenors.

FIGURE 35.2 Importance of the Core Group