Creating a Culture of Collaboration in a City Government

CULTURES OF COLLABORATION invite stakeholders to participate together in ways that support the organization’s mission, enhance the personal development of its members, and provide a needed service to the community with a vision of creating a better world.

My work with senior and mid-level managers in a United States city government serving a diverse, rapidly growing population of over 900,000 provides a process model for creating a culture of collaboration. The city manager I worked with knew that a culture change was needed and he had already begun that process when we first met. As happens in most organizational culture changes, he had brought in new managers that were committed to collaboration, and there were many managers who had been with the organization for years who were uncertain about what the culture change would mean to them.

The focus of our initial efforts was to design an event that would have a transformative effect on the team, creating both an experience of collaboration and launching their continued cultural change efforts. We decided on an off-site, two-day retreat, the planning for which would be a collaborative effort between a steering team of volunteer senior managers and me, as facilitator.

I use an action research framework, that mirrors the participative engagement I hope to help embed in the organization’s culture. Reason (2001) defines action research as a “participatory, democratic process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes, grounded in a participatory worldview.” He states that it “seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities”(p.1). As such, it serves as a way to engage with others in understanding the need for change and designing and implementing the change. Participants gain both the knowledge and the skills needed to create and sustain their own change.

Honoring an important principle of action research, I do not present myself as an expert consultant, but rather as a participant in the process, acting in the role of co-designer and facilitator. In preparation for the retreat, I asked to interview all participants to gain their perspective on the current situation and desired outcomes for the event and to personally invite them to participate in a way that could result in the transformative experience we hoped to enable. Taking care to protect confidentially, I shared the themes from these interviews with the design committee. This effort of co-construction ensures that the organization’s objectives are met and that all participants see their perspectives and objectives reflected in the design.

Not all members of the senior management team were eager to participate. Many were skeptical that it would be one more retreat, like previous ones that ate up their time with minimal results. The invitation I extended during the interviews uncovered limiting beliefs and assumptions and challenged participants to consider the possibility that something different could take place. I spoke of the importance of their participation in co-creating a new culture.

One participant told me that he had never fully participated in previous retreats. He described his pattern of showing up at some point during the first day, observing the process, confirming his belief that it would not create change, and returning to his more important work back at the office. If he had extra time, he might show up for a short time toward the end of the retreat. He described how he felt his work didn’t require the same type of collaboration, as did others who performed more central tasks. His previous experience led him to believe that this retreat would be the same as all the others and he was pretty certain he wouldn’t have time to attend the entire session. I asked him to challenge his assumptions and consider participating fully, stressing the importance of his contribution. Although he made no commitment to do so, he showed up at the beginning of the retreat and stayed until the end, fully participating throughout.

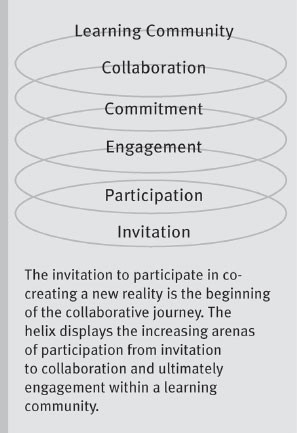

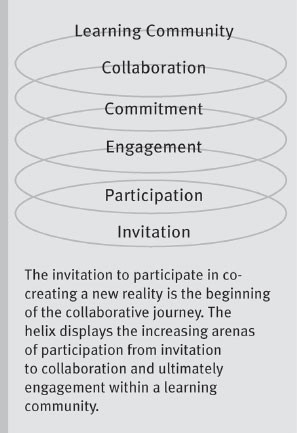

The helix in Figure 47.1 displays the increasing arenas of participation from invitation to collaboration and ultimately engagement within a learning community. Once we accept the invitation to participate in new ways, we create the possibility to become engaged in the process. When the engagement leads us to question assumptions, see the problems in old patterns of action, and the opportunities in new possibilities, creative energy is set free and people become committed to the change. If we believe in the power of intention, then commitment to change is the key to realizing that which we want to create. In this case, the commitment leads to collaboration that has the potential of evolving into a learning community.

FIGURE 47.1 The Collaborative Journey

The importance of an invitation to participate cannot be underestimated. A good invitation communicates the importance of the change effort to the organization, as well as the larger community it serves, and addresses the benefits to individuals. How will they develop leadership skills and capabilities through the process? How will they increase their ability to do their jobs and accomplish their goals?

The senior management team members were clear about their responsibility as public servants and acknowledged the importance of extending an invitation to collaborate to city employees, city council members, and city residents. Leaders of these efforts need to create time for questions and be open to hearing perspectives that challenge their intention. They also need to create the conditions that foster collaboration.

Five Conditions for Collaboration

The primary responsibility of leaders working in participative cultures is to create the conditions that enable people to achieve the desired result. I have found that five conditions are needed to support collaboration. People need to engage in meaningful relationships with others and in work that serves a greater purpose. Cultural competence is needed to recognize the value of different perspectives and communicate effectively across cultures. The culture needs to value shared leadership and prepare everyone to participate as a leader. Communicative competence embedded within dialogic communication fosters mutual respect, and enables knowledge to be shared, assumptions to be challenged, and learning to be ever present.

The event/retreat we crafted to launch a culture of collaboration for the city government established a foundation for all of these conditions. The first step in moving people into a collaborative space is to create opportunities for them to challenge their assumptions, shift their beliefs, and create new mental models. Collaboration requires beliefs that include the following:

• I can be more successful with the help of others.

• Diversity makes us more creative and capable.

• Disagreement adds value to a conversation and results in better decisions.

• Talking about what we have learned is more valuable than talking about what we have done.

• I can speak freely and truthfully to anyone in the organization.

Unfortunately, these beliefs are rarely held in most organizations. Individual beliefs will not be changed by telling people which ones they need to hold. Beliefs are changed through experiences that challenge our assumptions and cause us see ourselves in relationship to others, our organizations, and our world, in new ways. The retreat incorporated the five conditions in the following way.

Meaningful relationships were established through a process of individuals, within groups of five or six people, sharing aspects of themselves that are not normally shared in organizational contexts. Questions such as “What influences (culture, events, people) have shaped you?” “What do you value most about yourself, your work, your life?” “What are your talents, passions, and hobbies?” and “What are your aspirations?” guide people into conversations that reveal their authentic selves and develop new appreciation for each other. Every group I have guided through this process is amazed at the depth of the conversation that emerges and the closeness they develop with their colleagues. A window is opened to appreciating the diversity of the group. Understanding and appreciating diverse perspectives is the first step toward cultural competence.

Shared purpose is established through reflective conversation about the importance of the work of the organization. Inspiration and energy abound when groups of people talk together about how they contribute to a larger purpose. It is easy for all of us to get lost in the minutia of our daily tasks and lose sight of the meaning of our work. Collaboration is fostered by continually bringing to light how others are served by the work we do together.

Shared leadership is established by thinking and talking together about shared accomplishments, challenges encountered and overcome, and what has been learned along the way. These are simple but powerful conversations that don’t occur often enough in most organizations. Sharing leadership means that we recognize the strengths of others, are willing to speak openly, listen carefully, and take action together. Shared leadership requires trust, a willingness to grant authority to others, assume authority when needed, and provide the resources to enable others to act.

Communicative competence and dialogic conversation emerge quite naturally within a context that is established by good guiding questions and a process that provides everyone an opportunity to listen, reflect, and speak. The core of communicative competence is the intention for communication to reach new understanding for the purpose of informing individual and collective action. Communicative competence is based on Habermas’ (1985) four principles of mutual comprehension, shared values, truthfulness, and trust (see Figure 47.2).

Dialogic communication also stems from the intention to reach new understanding through inquiry, challenging assumptions, and advocating through engagement of the four principles.

While each of the four principles needs to be present for communicative competence, each communicative event has differing qualities of principle. Managers, whose relationships are lacking in trust and mutual comprehension, might improve their communication through establishing shared values and taking risks with truth telling.

FIGURE 47.2 Communicative Competence

One of the processes the city managers engaged in involved courageous conversations. This process places people in groups where they most often associate and where natural tensions exist. Often these groups are comprised of individuals from operations and administration, or manufacturing and sales and marketing. Each group is asked to discuss questions such as “How do we add value?” “How can we better collaborate?” “How can we better serve our colleagues?” and “What do we need from others to enhance our effectiveness?” Once the group discussions are complete, each group is asked to speak to the other groups, responding to each of the questions.

The conversations that emerge break through many of the existing beliefs and assumptions and create new insights critical to developing collaborative mental models. People recognize how they often blame the other groups for problems that they contribute to creating and maintaining, and they realize that by changing their own patterns of action, they can change the nature of the relationship. They gain new respect for others and the contributions they make, establishing greater trust and mutual understanding. Through these conversations, they experience communicative competence and strengthen the four principles to enable future conversations to reach new understanding through dialogue.

These five conditions are necessary elements of all highly participative cultures. The work described thus far strengthened relationships and created the spirit of collaboration. Changing organizational cultures requires a greater systemic approach.

Changing Organizational Cultures

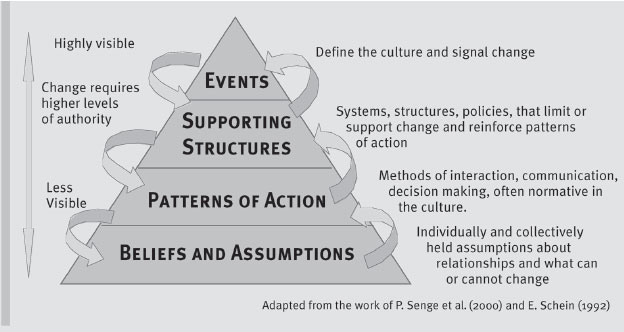

Cultural change involves change in collective and individual beliefs and assumptions, patterns of action, organizational supporting structures, and events. The model in Figure 47.3 shows how these four elements are addressed concurrently.

FIGURE 47.3 Cultural Change Pyramid

The pyramid shape shows how beliefs and assumptions create the foundation of a culture. Schein (1992) discusses how basic assumptions are so embedded within a culture that they are rarely recognized or discussed. Behavior based on basic assumptions is often taken for granted, as over time we become unaware of how our thinking has shaped our actions. Individual behavior based on beliefs, assumptions, values and experiences, eventually forms patterns of actions. These patterns are communicative, such as the way people contact and follow-up with each other, engage in meetings, and make decisions. These patterns are based on both the written and unwritten rules of the organization and reflect what people believe is valued and recognized or rewarded.

Supporting structures are constructed on the values and basic assumptions of the founders and senior leaders. Supporting structures include policies and procedures, performance review processes, rewards and recognition, and technology; the infrastructure of the organization that influences how people engage and take action. To support collaboration, supporting structures need to be aligned with the desired action and interaction, to provide the leverage to propel change. For instance, an investment in the right technology can enable collaboration outside of the limitations of time and space. Adding collaboration as a performance measure can demonstrate the importance of it and provide a structured opportunity for managers to address it, hold people accountable, and recognize success.

Events, planned or unplanned, publicly communicate what the organization believes and how it carries out its work. Like supporting structures, events create leverage for change. They provide leaders an opportunity to demonstrate their commitment to collaboration. They also provide opportunities to bring people together to envision new possibilities, experience new ways of working and create action plans for change.

During the two days the city’s senior managers spent in retreat, they worked together identifying the changes needed within the organizations’ culture to support collaboration among all people internally, with the city council, and with the public they served. Below are some of the points made in response to the work they needed to do.

• Staff must be helped to recognize their own importance.

• Employees’ personal performance objectives need to be connected to the corporate priorities.

• Rewards for collaboration are needed.

• Roles within a culture of collaboration need to be defined.

• It remains critical to hire and promote good people, and to help them assimilate into the culture.

• We need to anticipate the management skills needed in the future and train for them, rather than simply focus on the skills needed today.

• More improvement can be made on fully engaging the whole organization and getting them all to recognize that we serve the same customers.

• The organizational structure and physical locations of our facilities can be a barrier to collaboration. We can consider how to reorganize.

• We need to start acting as if we are already working together in one building (a new city hall was being planned).

• Resources need to be brought together to deal with issues, rather than being protected in silos.

The senior managers determined that a key action was to have their direct reports engage in a similar process and then talk together about their shared vision and ways to implement it. They valued the opportunity to develop their relationships and engage in meaningful conversation and they wanted their direct reports to experience a similar process. We co-designed a one-day retreat that engaged the next level of middle managers in a similar process and brought the two groups together for a dialogue about the changes they wanted to make to foster collaboration.

Results of the Effort

The retreat provided an opportunity for the senior managers to work together in new ways. The event signaled a change in the nature of their relationship and their organizational culture. They realized how many common values and aspirations they shared and how committed each of them was to serving the public good and creating an organization that enabled collaboration among all stakeholders.

Collaborative efforts continued to grow following the event. The city held two economic summits that brought together scholars, technology leaders, real estate brokers, merchants, and representatives from arts and non-profit groups. The city manager considered the summit a significant catalytic event as it brought stakeholders into a dialogue that could support collaborative action in improving the economic future of the city. The city also collaborated with the local university to construct a new library that served the whole community.

Ultimately, the result of creating cultures of collaboration is the development of learning communities with the capacity to work together, take risks, disagree, make mistakes, learn from those mistakes, and continue the collaborative efforts. If collaboration doesn’t extend into a learning community, when difficulties arise, people often revert to independent action. What does it take to keep these efforts going? When I asked the city manager to reflect on what he had learned from his efforts, he offered the following insights:

• Collaboration is built upon the professionalism of department heads and staff. The right people with the desire to work together and the knowledge that they are all serving the same constituency can accomplish great things. The city manager gives these senior managers total accountability and expects them to work together to meet the needs of the constituents.

• When people embrace collaboration they are willing to make personal sacrifices for the good of the whole. The city manager spoke about the budget process, where the city faced a $70 million shortfall. He described the organization as “breezing through it” as the managers worked together to make the cuts that were best for the city. Rather than taking the common position of protecting one’s turf, he stated that the managers offered to make the necessary cuts, negotiated with one another, and committed to support each other.

• Trust the people and the process even when mistakes are made. This leader faced difficult situations where his style of management came under fire from city council members, due to mistakes made within the organization. Yet, he expressed no hesitation in continuing to pursue his vision of a collaborative culture and to trust the people whom are close to the work. He is committed to making sure the group learns from the mistakes, reviews the patterns of action that created the problems, and establishes supporting structures to avoid similar situations in the future.

• Recognize that not all people will see the value in a participative culture. Members on the city council often questioned why decisions were delegated to lower levels in the organization and why more control was not exercised. All too often, leaders who feel strongly about participative cultures have pressure to exercise more control.

Unfortunately, this leader decided to leave the city manager position earlier this year because of the challenges he faced working within a larger culture that holds different values and expectations. This work requires those of us who believe strongly in the human values of participation to work to shift beliefs and assumptions at the community, national, and global levels. That task is not an easy one, yet it is critical to realizing the ideal of cultures of participation.

Guiding Beliefs and Assumptions

My work is guided by a set of beliefs and assumptions that I have embraced through my study of organizational learning, transformative education, and hermeneutic philosophy. These assumptions guide the way I participate with others in my life and my work and I believe create the conditions for transformative learning for others and myself.

• I participate with others in co-creating the future. The fabric of this co-creation is “care” for one another and for the world.

• We are always in relationship, so the work needed is to strengthen our relationships through understanding our shared values and aspirations.

• Relationships are strengthened through our communicative competence, a way of being in the world.

• Leadership is enabled through granting authority to others and through assuming authority when granted. Granting authority graces a relationship and creates a space where we can belong and participate together.

These assumptions are more other-centered than self-centered, and, as such, enable working cross culturally. The shift to being more other-centered is important if we are to embrace our differences and care enough to create cultures where we can participate together in creating a better world. I believe the purpose of creating participative cultures is what Mary Catherine Bateson considers composing a life. We don’t compose our lives alone. We co-create them through the relationships we have with others. Bateson’s (2004) work speaks to the integration of people, culture, relationships, and care. She states: “More and more it has seemed to me that the idea of an individual, the idea that there is someone to be known, separate from the relationships, is simply an error … we create each other, bring each other into being by being part of the matrix in which the other exists.” (p. 4). When we can bring all of who we are to our work, share our traditions, our joys, our struggles, and our aspirations, and come to appreciate the richness of our diversity and common purpose, we can co-create participative communities, where care and respect are weaved together to form the fabric of our organizations and our world.

References

Bateson. M. C. (2004). Willing to learn: Passages of personal discovery. Hanover, NH: Steerforth Press.

Habermas, J. (1985). The theory of communicative action, vol. 1: Reason and the rationalization of society, vol. 2: Lifeworld and system: Functionalist reason. (T. McCarthy, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press. (Original work published 1981).

Reason, P., & Bradbuy, H. (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Schein, E. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Southern, N. (2004). Creating cultures of collaboration that thrive on diversity: A transformative perspective on building collaborative capital. In M. Beyerlein & S. T. Beyerlein (Eds.), Advances in interdiscipinary studies of work teams (V. 11) (pp. 33–72). Maryland Heights, MO: Elsevier.