Global Leadership

A Virgin Landscape for OD Practitioners in the Vanguard

IT’S A RARE TREAT as an OD practitioner to have an opportunity to be in the vanguard, isn’t it? Often, practitioners find themselves asked to adapt to and adopt trends and tools fueled by media attention. Much of the language of OD has been absorbed into organizations—a good phenomenon but also one that makes some important and useful concepts seem “been there, done that” and trite. Bookshelves and file cabinets are brimming—some would say choking—with texts, popular books, and articles on leadership, change management and effective communications. Certain assessment tools, once viewed as cutting edge, can feel like standard fare and old news at times. Coaching, executive coaching and life coaching are sometimes almost too familiar with 60,000 people in the U.S. identifying themselves as professionals in these realms.

Yet, to borrow an old phrase, “every once in a blue moon” something shifts in the organizational landscape. Forces converge and a heretofore unknown and unmet need begins to come into view.

Personally, I became convinced that I was witnessing such a phenomenon during a two-year period that I was completing a global research initiative called “The Whole World at Work: Managers Around the World Tell Us What Still Needs to Change in Organizations” (Compel Ltd.). The undertaking was designed to detect global patterns in manager views about the “ideal” organization of the future, what works in change, and effective leadership qualities (see Table 72.1). By the time I was done, I had interviewed or completed focus group work with managers in 40 countries. But during the process, I began to detect an emerging organizational development need exemplified by the following excerpt:

We will open 64 hotels in China. We are having an issue coming up with an international management profile … Where do you get personnel, and what do you train them to do? [The company is] insisting that European and Asian managers [come] to Washington, D.C., and we’re going through training together … It’s important because our company is going to change, and our customers are going to change.

The interviewee was and still is a vice president and general manager for an international hotel and hospitality company based in the U.S. As a subsequent conversation and follow-up underline, and as a number of other interviews and environmental signals confirm, this business leader is not alone in his challenge. Executives and managers increasingly face a complex organizational dilemma in this era of accelerating globalization. “Tell me, please” more than one manager will say, “what I can do to help this organization think and act more globally!”

TABLE 72.1 Emerging Convergence (E-vergence) Summary Framework

My own experience indicates that executives and managers across industries and hierarchies are being challenged to craft more global strategies, policies and practices, and there’s evidence to boot. The average size in square feet of a Wal-Mart store in China is now bigger than the U.S. average; new and surprising mergers are occurring across borders on all continents; and organizations in general face growing demands for better coordination of globally dispersed operations. Companies are relocating facilities closer to lower-cost resources essential to production. Even small and mid-size companies are compelled to think of themselves as multinationals and adopt new habits for global success. Driven by competition and survival instincts, managers are forced to consider cost, logistics and human resources on a global scale.

All of this represents a fundamentally different kind of globalization than we have known in the past. Expansion is not just geographic, involving test entries into new markets or finding long-distance and low-cost suppliers. A new level of organizational connection and complexity has developed from wider, faster and more virtual flows of goods, services, knowledge, project travel, and influence. Moreover, several surveys point to an executive perception that there is a scarcity of managers qualified to work effectively on a multinational scale, and that in turn has become a constraint on future competitiveness. These leadership shortages are viewed as a damper on organizations’ abilities to meet future global business risks.

Consequently, consulting with and coaching managers on topics related to achieving global competencies and competitiveness is one of today’s pressing organization development challenges, raising a host of previously unanticipated issues and questions for OD practitioners:

• How do I help organizations define and design more global structures, systems and strategies?

• How do I work with my clients to think across and interact with fast-changing, far-flung organizations?

• How do I do so in ways that are specific to the organization’s unique needs and circumstances?

• How do I deal with the big, hairy challenge of developing leaders with a global mindset for the 21st century—those that Schon Beechler and Mansour Javidan (2007) define as: “a new and different breed of global leaders who can make decisions and take actions that facilitate the development of the complex network of internal and external connections with individuals, teams, and organizations with many different political, social, and cultural systems.”

The big missing factor is that the organizations comprised of evolved leader clients with whom OD practitioners can partner on these opportunities mostly do not yet exist. I often refer to the people who comprise this leadership approach as “The New Hybrid Leaders,” and describe them as multi-dimensional individuals who are equipped with “transformational,” “transnational,” and “trans-cultural competencies.” The New Hybrid Leaders would consistently behave and be recognized as global citizens, eager to:

• Integrate, respond to, and lead diverse groups;

• Demonstrate situational flexibility in management style;

• Be effective in a variety of geographic, cultural and dual-gender settings.

No Roadmap or Best Practices

The fields of organization development and human resources also haven’t kept pace. A ready set of principles and approaches to which practitioners can refer for learning and support is lacking. Even though the term “global” was first applied to executives and jobs in the early 1980s, organizations, professional practitioners and academic researchers have mostly continued to think domestically. There remains a near negligible percentage of organizational and human resource management articles published in leading management journals and devoted to international topics.

Conferences and workshops around the world generally focus on transferring North American approaches to management, leadership, and change, as opposed to integrating views into more globally relevant approaches. Few meaningful case studies exist on effective global management approaches, and the literature reads like a catalogue of proposed leadership traits. In a phrase, the notion of developing global organization and leadership skills is in its nascent stage.

On a personal note, I’m regularly struck by the degree to which we remain insular and localized in our thinking about organizational needs. At this year’s annual Society for Human Resource Management Global Conference and Exhibition, I led a discussion on developing global leaders and was initially pleased with interest and participation. Only in retrospect did I recognize the obvious. Attendance at the conference was disproportionately American, but three-quarters of my discussion participants were Austrian, Polish, Indian, and French. This global conference for HR professionals, the attendees eager for information on leadership development with a global outlook, hailed from outside the U.S. Similarly, I recently noticed that the 2009 program for the largest annual HR summit in Asia, with anticipated attendance of more than 3,000 Asian professionals, features a roster of keynote speakers almost entirely from the U.S. and U.K. Strung together with other similar events, a pattern emerges. In a time when global diversity is an inherent driver, ethnocentricity is still ingrained in the way we think about and guide organizations.

Moreover, as confirmed by “The Whole World at Work” interviews that I referenced earlier, there exist several habitual barriers that generally get in the way of organizations moving beyond a focus on how we do it around here, and how we do it in this country—so to speak. These are organizational attitudes and behaviors that get in the way of development—are intrinsically present in what we often think of as a U.S. management style—and are being broadly exported and emulated outside North America. The barriers can be categorized as:

• Policies and practices perceived as not valuing people

• Over-reliance on technology and process for change

• Emphasizing only cost and performance measures

• Under-investing in training and development

• Dragging on diversity

• Re-structuring without reasoning

These taken together get in the way of envisioning, developing and implementing new approaches more consistent with likely organizational futures.

Need for OD Reflection

However, this stark reality can be viewed as good news of a sort. The disconnect between the need for integrated, multinational outlooks contrasted with a paucity of supporting tools and available resources represents an exciting opportunity for OD practitioners. The landscape is wide open for forward-looking practitioners proposing and experimenting with new consulting and coaching frameworks in companies increasingly curious, even hungry, for ways to help their people “go global.”

For the willing, OD practitioners have blossoming opportunities to influence organizational structures, systems and strategies for multinational and multidimensional effectiveness. New organizational puzzles are yet to be resolved, pieced together from answers to questions such as:

• Will the profile of tomorrow’s successful leaders differ greatly from today’s?

• How important will the qualities of global mindset be to manager success?

• On what criteria should organizations select members into and facilitate multinational, multicultural teams?

• What should be the OD practitioner’s role in re-shaping training and development?

• What self-development and experiences do OD practitioners require in this global environment?

As globalization has evolved from corporate buzzword to basic economic reality, more organizations seek to competently operate in the international arena, but many organizations do not know how to identify and develop people for such complex responsibilities. As examples, organizers of annual state Human Resources conferences in Illinois, California and a tristate area of the Northeast added globally-focused topics to workshops for the first time in 2007. Value-adding practitioners will be those who offer thoughtful views on how many “global leaders” must an organization have; which managers should develop a worldwide outlook while others stick to their proverbial knitting; and which global leadership development interventions offer the best return on investment (ROI).

A Place to Begin

OD practitioners are in unique positions to launch dialogues on these issues and to contemplate ways to groom silhouettes of The New Hybrid Leaders through leadership development programs that acknowledge global realities and influences.

Where do OD practitioners begin when there is no vetted formula, scorecard, checklist or best practices? Moreover, how do they begin when they are under pressure to prove that management education options actually achieve change, and organizations are shifting away from long-term investments in education toward development that is short, intensive, flexibly delivered, and consistent with corporate objectives. Just as important, how does OD partner with HR practitioners and executive and manager stakeholders at a client site?

First and foremost, it’s essential to consider a range of parameters that can affect global organization and leadership development efficacy:

• Is the organization in question experienced or inexperienced on the global scene?

• When an organization has an established multinational history, how has it gone about preparing (or not preparing) managers to work in different cultures and contexts?

• Where should interventions take place and with whom? For instance, are the managers of interest a multicultural group all seated within the corporate headquarters? Or, will the work be done within a specialized function, like IT? Or, is the need greatest with sales and marketing professionals who are becoming familiar with new markets? At what organizational level are the executives/managers—C-level? Mid-level? Supervisors?

• What is the nationality or nationalities of the managers?

• What is the purpose of the development experience, and what time and financial resources exist to support the effort?

Many practitioners are surprised to hear that depending on circumstance, the range of options—even in this embryonic field of global organizational development—can be quite broad (and untested). Accepting and communicating that there is no full-proof one-day seminar, executive education program, or international degree is a sound and honest start. Therein, the art vs. the science of OD must take hold, with practitioners casting themselves as catalysts for exploration in three arenas: (1) prompting executives and managers to re-conceptualize their world in reference to the big, wide world; (2) exposing managers to development experiences that alter ingrained mental models and habits; and (3) facilitating conversations to re-think organizational designs in light of global realities. These best play out in thoughtfully-designed dialogue sessions that:

• Explore divergent ideas across geographies, functions, levels and cultures

• Embrace convergent ideas and build shared organizational understanding

• Address barriers to effective global operations

• Take into consideration which managers are equipped with a so-called “global mind-set”—a key component of global leadership because cognitive abilities (mindsets) influence how managers shape strategy, thus determining behavior and outcomes.

Consistent with this last point above, 360-degree assessments naturally become part of the organization and leadership feedback mix. A single 360-degree global assessment tool hasn’t yet been broadly used and validated, but it is possible to combine elements of several tools that help individuals and teams talk about the extent to which they do or don’t exhibit global mindset and an effective global leadership style. Working with colleagues and collaborators, I’ve moved toward several rating instruments, including: the Global Executive Leadership Inventory (GELI), complemented with a Whole Work™ work culture survey, further complemented by customized interviews. GELI was developed by Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries from investigations of the daily actions and behaviors of effective global leaders. Whole Work™ tools were inspired by research involving interviews with managers, consultants and coaches working in multinational companies on five continents. I supplement tools like these with narrative interviews designed with the organization in mind.

With assessment results in hand, OD practitioners can conduct exercises and simulations that help managers redefine paradigms from which they make decisions. One experience might involve working with a group to envision how to best choose members of an imaginary global team. Participants could receive information on a company’s business environment, strategies, and current leadership profiles; be provided with information on effective global leadership traits; and then, together, build the “best global team.”

Similarly, a cross-cultural consultant with whom I’m collaborating told me about a leadership development workshop that he conducted for a multinational company with operations in Asia. The company was a U.S.-China joint-venture, and the workshop took place in Beijing. As he recounts, participating America managers spent 45 minutes openly discussing their beliefs about leadership while the Chinese team members waited patiently. When the Chinese had their turn, they began to energetically discuss four different interpretations of “leadership” from their perspectives. Ten minutes after the non-English discussion began, the Americans asked if they could go outside until their counterparts were done. What an eye-opener it was for them when the facilitator pointed out how little room and tolerance they had for waiting to listen to the outcome of an alternative exploration of leadership concepts.

Whatever the methods, an overarching goal is always to help managers recognize beliefs and habits that help or hinder success on a global scale. That includes the degree to which individuals and their organizations appreciate diversity, adapt, think flexibly, and integrate previously unimagined and more expansive ideas and solutions. For OD practitioners, this entails determining processes and practices to facilitate individuals, groups, and organizations to achieve organization goals across diverse cultural and institutional systems.

Sharing Continuous Learning

Last but not least, and this gets to the heart and spirit of a member organization such as the Organization Development Network (ODN), the broadly defined arenas of global organization development and global leadership development offer opportunities for OD practitioners to begin documenting and sharing experiences for the purpose of continuous learning. In mostly uncharted territory, the programs and services that companies will ask OD practitioners to provide become a de facto learning laboratory on the role and efficacy of interventions on development of global mindsets and behaviors, as well as the interplay of organizational and individual factors on interventions. There is knowledge to be gained and shared.

For instance, I recently co-designed a development framework for use with a multinational company in the early stages of establishing a global leadership development discipline. As envisioned, participants will be distributed across several groups experiencing distinct development interventions. These groups are identified through a sample of managers in headquarters and overseas sub-units identified as “high-potential” within the organization, and accounting for characteristics of age, nationality, geography, functional specialization, and job level. The groups will participate in either a customized one-day diversity immersion experience intended to enhance global mindset; a three-day intensive program incorporating an overview of global leadership concepts and case study- and simulation-based dialogues; or a combination of the programs. For additional insight, there will be a comparison of the impact of the interventions with an “expatriate readiness” program already in place at the client. To measure changes, all participants will complete assessments of global leadership skills and global mindset before the interventions and at a specified point in time after.

This “global newness” to organization and leadership development presents a rare high-stakes, high impact opportunity for OD practitioners and their counterpart HR professionals to be in the vanguard. OD and HR remain the go to sources for people policies, procedures, principles and practices. They are often management’s eyes and ears for monitoring reactions and responses to strategic global decisions. Taking responsibility for developing organizations and managers with multidimensional, multinational outlooks is just one step removed.

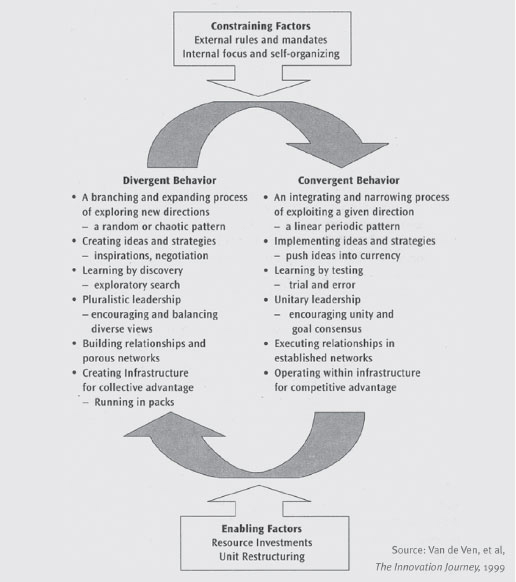

The challenge is to work through current ambiguities about how best to do this. In fact, I often say that global organization development is less about a checklist and more about pursuing what Andrew H. Van de Ven, et. al, called “Cycling the Innovation Journey” (see Figure 72.1)—an organizational process of exploring divergent ideas and exploiting convergent views about which ideas to implement.

FIGURE 72.1 Cycling the Innovation Journey

For one company, the vision might start with executive team alignment on what the global landscape will look like and who will be our leaders, continued with a proactive recruiting plan for high-potentials across multiple countries. For still another, a robust and culturally sensitive 360-profile of key managers with ongoing feedback might be appropriate. For another, perhaps the hiring of an anthropologist for a cross-creating forums and experiences in which cultural learning journey would be useful. organizations take time to ask tough but The approaches might be vastly different necessary questions: How global are we and highly customized, but would all going to be? And how must we change to have one thing in common. They involve get there?

References

Beechler, S., & Javidan, M. (2007). Leading with a global mindset. In M. Javidan, R. Steers, & A. Hitt (Eds.), The global mindset (pp. 131–169). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Van de Ven, A. (1999). The innovation journey. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.