OD 2.0

Shifting from Disruptive to Innovative Technology

PRIOR TO THE INTERNET, the last technological innovation that had a significant effect on the way people sat and talked together was the table (Shirkey, 2003). The web has transformed the way we communicate, learn, and work, and in the very near future, it will transform the way we practice organization development. In their second annual survey of Web 2.0 use in business, McKinsey reported a 25% increase in application adoption in just one year (Bughin, Manyika, & Miller, 2008). Their use of these technologies is also expanding from the sales and marketing arena to employee engagement. Organizations are using Web 2.0 tools to recruit, onboard, and develop their workers.

Web 2.0 technologies including blogs, wikis, social networking sites, and virtual worlds are more personalized and interactive than first generation web applications (Web sites and email) and offer opportunities for proactive participation, sharing, connectivity, and collaboration, the very underpinnings of OD practice.

As leaders in planned change, we can have significant influence over how organizations reinvent themselves in terms of performance and culture as they form a virtual identity. Practitioners must be comfortable enough with new technologies to support their use as communication tools, virtual work environments, and community building (Feyerherm & Worley, 2008). While Cyber OD presents new opportunities for consultants to increase organizational effectiveness using virtual technology, this expanding frontier requires the development of new methodologies to address the unique challenges it brings (Speake, 2008).

As many organizations implement internal social networking applications (Bersnen, 2008), they will be looking for guidance in how they might best utilize these technologies to facilitate change and improve organizational functions. They are looking for opportunities to implement widespread, global change quickly and efficiently. With greater emphasis on cost reduction, Web 2.0 technologies offer the opportunity to expand communication and interaction anytime, anywhere, allowing practitioners to reach members virtually. Teambuilding, product development, knowledge sharing, and relationship building, are just few of the processes that can be enhanced by Web 2.0 technologies (Bersin, 2008). Consultants are often asked to bypass the diagnosis and assessment stages (Feyerman & Worley, 2008), but corporate blogs, wikis, nings, and other virtual sources of communication can offer rich data that can provide a valuable source of information about an organization and its members’ beliefs and practices. By combining evidence based research and practical application we will explore this emerging field, developing a framework of OD 2.0 implementation

From Disruption to Innovation

In its infancy, Web 2.0 was viewed as another distracting element; a toy for college students and Gen Y workers that took them away from the important aspects of school and work. Nearly anyone with an Internet connection can be a web developer, creating wikis, blogs, virtual identities, even live a second life in a virtual world. The architecture of participation created by Web 2.0 moved the “average Joe” from the passenger’s seat to the driver’s seat of web knowledge creation. Over time, we learned from early mistakes and found ways to channel the capabilities of Web 2.0 technology to facilitate learning, innovation, and relationship building.

Web 2.0 tools allow employees at Dell, Starbucks and IBM to connect with each other to share ideas and information and form communities. IBM also uses social networking to capture expertise throughout the organization and 3M uses it for the sharing of ideas and research information among experts (Bersin, 2008). IBM’s internal social networking site, the “Beehive,” enables employees to create social networks and collaborate with fellow employees across the globe. Gensler, Honeywell, and Nestlé are using both external (You Tube) and internal streaming video to communicate culture, teamwork, and share best practices.

Web 2.0 has gone beyond blogs, wikis, and video to include a virtual world known as Second Life where conferences, learning and social networking events are hosted by hundreds of organizations as diverse as Harvard University, IBM, and Cisco. Participants create avatars and communicate with words and gestures. IBM is deeply involved in Second Life, using it as a medium to reach customers and connect staff. They are one of the first corporate users of Second Life to develop an enterprise system that allows its users to not only meet publicly, but to also move behind their corporate firewall to hold private sessions. Their IBM Academy holds multi-day virtual conferences that include many of the same components of a traditional conference including poster sessions, break out sessions, interactive training and discussion.

Another Second Life success story involves Margaret Regan, a diversity consultant who has created an island for her FutureWork Institute where she hosts diversity workshops and networking sessions. Participants can experience diversity first hand by inhabiting an avatar that differs from their own age, race or gender.

Table 78.1 contains a list of Web 2.0 applications and their potential uses in OD practice. Although this list is not exhaustive, it is good starting point for those who want to learn the talk or delve deeper into the various technologies. When working with clients who are currently utilizing Web 2.0 technologies, consultants must treat the technology as they would any other organizational practice, first assessing its contribution to organization function and then considering how it might best be utilized to support the change initiative.

Although interest in Web 2.0 value is building, and our chronicle of best practices grows, to truly understand the foundational issues of this phenomenon, we must move beyond examples to theory. As we move from disruption to innovation, we must find a theoretical landscape with which we can examine the benefits of Web 2.0 applications.

Theoretical Context

Social networking theory provides a rich context to examine Web 2.0 practices. Social networks are the formal or informal connections among people. Originated in the field of sociology, social network analysis has recently become more popular as Web 2.0 has evolved. Social networks are ties of goodwill, mutual support, shared language, shared norms, trust, and a sense of mutual obligation that add richness and value to our lives. The people in the networks are called nodes and their relationships are ties. Perhaps the most fascinating findings regarding social networks are the theories of weak ties and structural holes. When we move outside our typical landscape of relationships we receive greater benefit from the non-redundant information these “weak ties” provide (Granovetter, 1973). We further benefit from ties that span “structural holes” or the gaps in networks because they support the importing and exporting of new information and ideas between groups (Burt, 2000). Technology can support the formation of weak ties by connecting members across groups through blogs and internal social networks. Structural holes can be spanned virtually when members of different organizations connect in public blogs, social networks, or virtual worlds.

TABLE 78.1 Web 2.0 Tools Mapped to OD Practice

Web 2.0 Tool |

OD Practice |

|

Blog: User-generated website where entries are made in journal style and displayed in a reverse chronological order. Blogger: www.blogger.com Typepad: www.typepad.com |

• Knowledge management • Sensing and assessment • Data collection • Culture building • Communication |

• Project collaboration • Visioning • Building trust • Organization Alignment |

Wiki: a website that allows the visitors themselves to easily add, remove, and otherwise edit and change available content, typically without the need for registration. Wikipedia: www.wikipedia.org PBWiki www.pbwicki.com Wetpaint www.wetpaint.com |

• Communication • Project management • Knowledge building |

• Collaboration • Consensus building • Visioning |

Folksonomy: Collaboratively create and manage tags to annotate and categorize content. Metadata is generated not only by experts but also by creators and consumers of the content. Delicious: www.delicious.com Furl: www.furl.net |

• Knowledge management • Consensus building |

• Project management • Mentoring |

Social Networking: Websites that focus on community, encourage interaction, discussion, debate, offer public member profiles and user-generated content Linkedin www.linkedin.com Facebook www.facebook.com Ning www.ning.com |

• Relationship building • Mentoring • Teambuilding |

• Building trust • Onboarding |

Twitter: Communication tool that lets users publish updates under 140 words to answer the question “What are you doing?” via tweets, published on their website, IM, browser, or mobile phone Twitter www.twitter.com |

• Project management • Communication • Performance management • Assessment |

• Feedback • Networking • Relationship building |

Video Sharing: Users can upload, view, and share video clips You Tube: www.youtube.com Meat Team: www.meatteam.tv |

• Communication • Teambuilding • Group process • Knowledge management |

• Culture building • Visioning • Storytelling |

RSS Feeds: Allows you to stay current with all your favorite news, blogs and feeds--in one place Bloglines www.bloglines.com Google Rdr www.google.com/reader |

• Communication |

• Knowledge management |

Slide sharing: Share your powerpoint presentations publicly or privately, search thousands of presentations or join groups Slideshare www.slideshare.net |

• Project management • Knowledge management |

• Best practices |

Virtual Worlds: Build a 3D virtual world and explore, meet other residents, socialize, participate in individual and group activities, and create and trade property and services with one another, or travel throughout the world. Second Life www.secondlife.com Vivaty www.vivaty.com |

• Meetings • Conferences • Team building • Group process |

• Culture building • Training • Networking • Onboarding |

Social capital is defined operationally as the resources embedded in social networks that are accessed and used by individuals (Nin, 2002, p. 25), or the product of rich networks. Social capital has been linked to a variety of positive outcomes such as better public health, lower crime rates, and more efficient financial markets (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Participation in social networks allow us to draw on resources from other members of the network and to benefit from connections with multiple social contexts by sharing information, job opportunities, relationships, and organizing of special interest groups (Paxton, 1999). Executives who were educated to use networks to build social capital were significantly more likely to get top performance reviews, be promoted, and be retained by their company (Burt & Ronchi, 2007). As OD practitioners, we can not only facilitate the development of rich social networks among our clients, but also amongst ourselves. By connecting professionally via Linked In, developing our own blogs, creating and building wikis and nings, we not only connect with colleagues but can share our knowledge and promote our field.

Web 2.0 technology provides unlimited opportunity to span structural holes and create ties, both weak and strong, with internal and external constituents around the globe. No longer limited to the physical water cooler to form relationships and share knowledge, workers can now interact virtually with members anytime anywhere. Those who telecommute are no longer invisible, but can create a strong virtual identity that makes them a highly visible and valuable organizational member. Knowledge sharing in the Web 2.0 organization will become viral, spreading from person to person, spanning organizational lines and geographic barriers.

Although research and theory on social networks and social capital in virtual environments is in its infancy, a few studies had promising results. College students who participate in an online social network site demonstrate a robust connection between usage and indicators of social capital (Steinfield & Lampe, 2007). In the context of learning environments, Web 2.0 applications are excellent vehicles for experiential learning activities such as case studies due to their collaborative nature (Huang & Behara, 2007) and may support lifelong learning by connecting people in borderless collaborative environments (Klamm et al., 2007). Safran, Helic, & Gutl (2007) emphasized the potential of Web 2.0 to uphold critical and analytical thinking, facilitate intuitive and associational thinking, support analogical thinking through easily accessing to rich information and interacting with diverse opinions.

To respond quickly and nimbly to rapid change due to technological innovation and economic downturn and recovery, organizations must be able to generate, analyze, support, and communicate new ideas and practices beyond the borders of time and space. They must be able to foster collaborative thinking and action at every level of the organization. Web 2.0 technologies, though not an end all answer to every organizational challenge, can provide an additional arena for collaborative knowledge sharing, idea generation, and dissemination.

As Web 2.0 applications move from the disruptive to innovative, there are still drawbacks that must be addressed. Concerns about privacy, transparency, and a decline in face-to-face communication are of immediate concern as we expand virtual communication networks. In the following section we will explore the drawbacks of Web. 2.0 adoption.

The Dark Side of Web 2.0

There are several risks involved in implementing Web 2.0 practices. First, and perhaps foremost of concern is the need for privacy. We may erroneously assume that because we are communicating virtually, that we are invisible, but in reality, the privacy of individuals who use public social networks is limited. Many companies are using information posted by their members in online social networks (OSN) to make employment decisions (Genova, 2009). Although the legality of this practice is under debate, it is becoming common practice for organizations to scan OSNs when making decisions about hiring or promotion. In addition to concern about member privacy, organizations are also concerned about maintaining control of proprietary information, fearing that corporate secrets will fall into the hands of competitors, or that the organization image might be damaged by inappropriate comments. Next, as firms outsource more OD processing to third party vendors, extra care must be taken to protect the identities of those that provide information. Questions also come into play regarding who actually owns the data that is provided and for how long it will be stored in various databases.

To control for these potential risks, best-practice organizations develop a clear policy statement about appropriate use and behavior of Web 2.0 tools. For example, IBM has developed a clear policy on social computing (www.ibm.com/blogs/zz/en/guidelines.html) and found that group norms have controlled potentially negative communication.

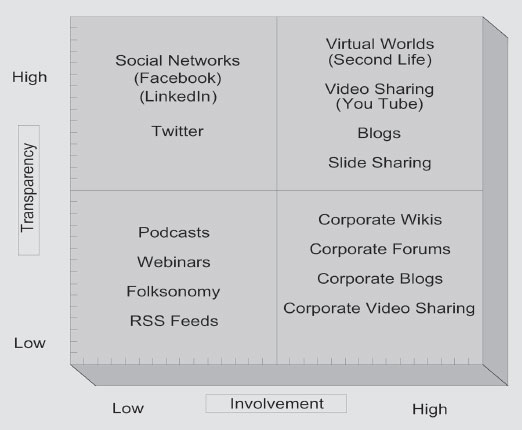

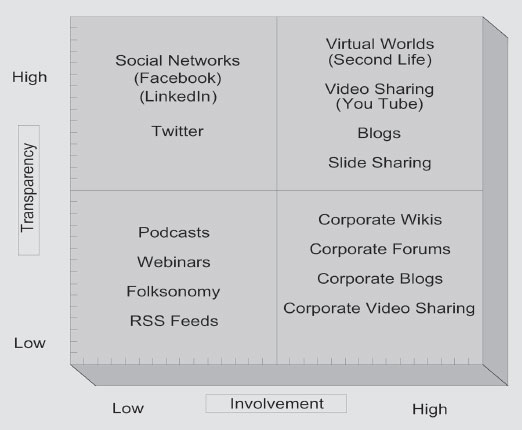

Figure 78.1 contains a diagram that assesses both the transparency (public domain) and involvement (creative opportunity) of various applications. Some activities like listening to podcasts, viewing webinars, contributing to folksonomy, and managing RSS feeds are neither particularly transparent nor do they involve a lot of creative contribution on the part of their users. On the other hand, participation in applications such as Second Life, blogs, producing You Tube videos, and slide development can be highly transparent and also highly involving. Organizations can reduce the transparency of some of these applications by adopting an enterprise Web 2.0 system that limits public access.

FIGURE 78.1 Web 2.0 Applications and Levels of Transparency and Creator Involvements

Not only are social networks changing the way we do business, they are also changing the way we communicate and connect with others. As we spend more time communicating virtually, we have less time to connect in our physical worlds. As electronic media use increases, time spent in face-to-face social interaction decreases (Sigman, 2009) and this lack of social connection can affect our emotional and physical well-being. Although other researchers present a positive view of socialization and internet use (Shapira, Barak, & Gal, 2007), we must be cautiously optimistic about virtual communication, ensuring that we do not lose track of our first life by spending too much time in Second Life.

Next we will examine a framework for initiation and implementation of OD 2.0 applications with a focus on both potential benefits and limitations.

Initiation

The initiation of Web 2.0 technologies due to its open and participatory nature readily lends itself to an action research process. The “felt need” that triggers organizational change initiatives is evident in the widespread use of the social networking applications in our society. As we look for ways to bridge the gaps of time and space, we turn to social networks to create connections that would otherwise be impossible. It is only a matter of time until these new venues for communication permeate organizational practice. Web 2.0 is also pull technology by nature. People who are excited by it use it, and get others excited, creating the opportunity for emergent change.

As we initiate Web 2.0 practices in organizations, we might submit them to the spiral of steps and the circle of planning, action, and fact finding that defines action research (Burns, 2006, p. 140). For example, we might look carefully at how group communication changes when it takes place in a blog as opposed to a face-to-face meeting, noting the benefits and deficiencies of each mode. Participants become co-researchers engaged in cogenerative dialogue as they ask questions to guide their understanding (Elden & Levin, 1991). Questions that guide action research such as “was it ethical, democratic, collaborative?” and “did it solve practice problems or did it help us to better understand what will not solve our problems?” will provide insight and guidance as we explore and learn about these technologies.

Implementation

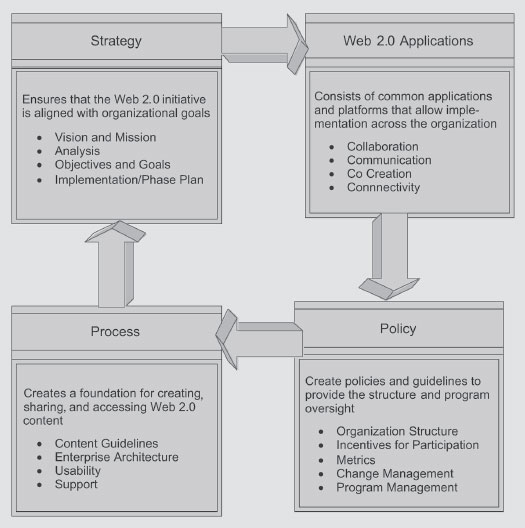

If action research indicates a need for a broad or full scale adoption of Web 2.0 practices, then a framework for implementation can provide structure to the process (see Strategy, Policy, Process, and Application in Figure 78.2).

First, focus on developing a strategy and vision for the adoption of Web 2.0 technologies. Consider how it will contribute to the overall organizational vision and mission. Information gathered from action research during the initiation stage can provide rich data to guide this process. This information will drive the features, function, specifications and benefits of the technology that you choose to provide a unified mission and overarching goals as you move forward with the implementation. You might use a scenario planning approach to “test” the feasibility of various strategies. You may also develop a business case for the implementation, further communicating the value added components of the technology.

Next, it’s time to consider the application. First and foremost, consider ease of use. Those who are active in public social networks, blogs, and virtual worlds are accustomed to platforms that are highly intuitive and user friendly. Internal delivery systems must mimic the simplicity of Facebook, Blogger, and Wikipedia if they are to be widely accepted and utilized. Consider tools that will comply with the current infrastructure and that can be customized to fit your need.

FIGURE 78.2 Web 2.0 Implementation Framework

When you consider the policies that will guide the implementation and management of the Web 2.0 system, first think of how you will garner buy-in from top management and organization members. An infrastructure must be in place to shepherd the system and incentives must be available to encourage participation. Just because you build it, don’t assume they will use it. Empty blogs, wikis, and virtual worlds will become wastelands without the active involvement of members. If collaboration and collective participation were part of your initiation process, then active involvement should follow.

Finally, think about process or how the system will operate. Consider whether you will adopt a complete enterprise system or will have some opportunity for public connection outside the organization. Also, think about how much freedom members will have to create their own content and use the tools to create special interest groups. Also consider how information will be tagged and catalogued so that future users will have quick and easy access to knowledge creation.

As we initiate and implement new social networking technologies, we must continue the planning, action, and fact finding process. Just as we can’t understand an organization without trying to change it, we can’t understand technology without continuous improvement.

As technology becomes more pervasive in OD practice, we must always keep in mind that it is nothing more than another tool and that good OD whether delivered in face-to-face conferences or in a virtual world is still good OD no matter the delivery system. Yet we cannot put our heads in the sand and ignore the Web 2.0 revolution no more than our ancestors could ignore the invention of electricity. It is here to stay and its effect on the way we communicate will be dramatic and pervasive. As professionals who are committed to continuous learning, we must view the new world of virtual social networks as another opportunity to expand our area of expertise. If you are not part of the online social network explosion, it is time to get on board (see Table 78.1); start by joining LinkedIn; get a Facebook account and see what your teenagers (or your neighbor’s teenagers) are up to; visit some blogs or start your own blog; create an avatar and wander around Second Life; add to a Wiki or create one of your own; at least check out Twitter; and of course, You Tube. As you become more comfortable in our new virtual world, consider ways that you might enhance your practice with these tools. Start slowly, document your results, share them with others, and contribute to the overall knowledge base of this exciting new frontier.

References

Adler, P., & Kwon, S. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40.

Bersin, J. (2008). Social networking and corporate learning. Certification Magazine, 10(10), 14.

Bughin, J. Manyika, J., & Miller, A. (2008) Building the Web 2.0 Enterprise: McKinsey global survey results. Retrieved from http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/building_the_web_20_enterprise_mckinsey_global_survey_2174

Burns, B. (2006). Kurt Lewin and the planned approach to change. In J.V. Gallos, & E.H. Schein (Eds.) Organization development: A Jossey-Bass reader, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Burt, Ronald S., & Ronchi, D. (2007). Teaching executives to see social capital: A field experiment. Social Science Research, 36, 1156–1183.

Elden, M., & Levin, M. (1991). Cogenerative learning: Bringing participation into action research. In W. F. Whyte (Ed.), Participatory Action Research. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Feyerherm, A., & Worley, C. (2008). Forward to the past: Reclaiming OD’s influence in the world. OD Practitioner 40(4), 2–8.

Genova, G. (2009). No place to play: Current employee privacy rights in social networking sites. Business Communication Quarterly, 72(1) 97–101.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. The American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Huang, C.D., & Behara, R.S. (2007). Outcome-driven experiential learning with Web 2.0. Journal of Information Systems Education, 18(3), 329–36.

Klamma, R., Chatti, M.A., Duval, E. Hummel, H., Hvannberg, E. H., Kravcik, M., Law, E., Naeve, A., & Scott, P. (2007). Social software for lifelong learning. Journal of Educational Technology and Society, 10(3), 72–83.

Lin, N. (2002). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105(1), 88–127.

Safran, C., Helic, C., & Gutl, C. (2007). E-Learning practices and Web 2.0. Proceedings of ICL 2007 (pp 1–8). Villach, Austria.

Shirkey, C. (2003). A group is its own worst enemy. Retrieved from "http://www.shirky.com/writings/group_enemy.html

Shapira, N., Barak, A., & Gal, I. (2007). Promoting older adults’ well-being through Internet training and use. Aging & Mental Health, 11(5), 477–484.

Sigman, A. (2009). Well connected? The biological implications of social networking. Biologist, 56(1), 14–21.

Speake, S. (2008). Cyberspace and the OD Profession. OD Practitioner, 40(4), 60–61.

Steinfield, N., & Lampe, C. (2007). Spatially bounded online social networks and social capital. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4).