The Philokalia and the Inner Life

For Joy

A loyal wife brings joy to her husband

(Sirach chapter 26, verse 2a)

I am indebted to many people who have helped me with my research into the Philokalia. First and foremost, I must acknowledge my enormous debt to Andrew Louth. It was he who conceived this project, who recognised its links with my previous work and interests, and who invited me to work with him on it. Subsequently he undertook to be my PhD supervisor when we agreed that the project would involve my submission of a dissertation as well as preparing a book for publication. He has offered invaluable comments on all of the manuscripts, including the very earliest drafts. I have learned so much from his gentle but incisive wisdom and spirituality and his encyclopaedic knowledge of Christian theology.

Most of the writing, including almost all of the initial chapter drafts, was undertaken on Holy Island, whilst staying in Cambridge House as a guest of the Marygate Community. They have made me warmly welcome, even amidst some severe Northumbrian weather, and I have appreciated the rhythm of daily prayer at St Mary’s Church during my stays there. This has helped me to remember that thoughts and prayer really are linked inextricably, and that it is not possible to write on a subject like this with integrity without also being immersed in a community of prayer. The work was finished at St Deiniol’s Library in North Wales, with the support of a Richard L. Hills scholarship, and I am therefore also grateful for their generous hospitality.

The Leventis Foundation and the Society of the Sacred Mission have kindly supported my work on this project with generous grants, for which I am most grateful. It would not have been possible to undertake this work without their support.

I am very grateful to Kallistos Ware and to Renos Papadopoulos for their helpful comments on the PhD dissertation which became the basis for this book. I am grateful also to Andrew Powell for his comments on an early draft of the chapter on psychotherapy.

I am grateful to Liturgical Press for allowing me to quote material from The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward: Copyright Sister Benedicta, 1975. Revised edition 1984. A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN. Reprinted with permission.

Material from Evagrius of Pontus: The Greek Ascetic Corpus by Robert E. Sinkewicz (2003) has been used by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc.

Finally, I must thank my family for their love and support throughout the period of my work on this project, and especially my wife, Joy, who has often been in my thoughts and prayers. This book is dedicated to her.

Many of the names of authors of the Philokalia are susceptible to differing transliteration. The spellings employed in the English translation of the Philokalia have been used throughout in this book, except where quoting from other published work.

Many of the authors of the Philokalia are saints of the Christian Church, and are referred to as such in the text of the Philokalia. For simplicity, and to avoid making distinctions in the present context, they have been referred to here without the prefix of “Saint” or “St”. This also avoids the difficulty, as in the case of Evagrios, of deciding what to do when the person is recognised as a saint of one part of the Church but not another.

[Name] The use of square brackets around a name indicates that a text is attributed to the named author but that it is in fact no longer considered to have been actually written by that author. Unless otherwise indicated, this means that the true author of the text is now unknown.

Titles of works included within the English translation of the Philokalia have been abbreviated according to the list of abbreviations provided at Appendix 1.

Abbreviations used for titles of the works of Evagrios

Foundations The Foundations of Monastic Life: A Presentation of the Practice of Stillness (included in the English Philokalia as Outline teaching on asceticism and stillness in the solitary life)

To Eulogius To Eulogius. On the Confession of Thoughts and Counsel in their Regard

Eight Thoughts On the Eight Thoughts

Praktikos The Monk: A treatise on the Practical Life

On Prayer Chapters on Prayer (included in the EGP as On Prayer: 153 Texts)

Other works of Evagrios, where mentioned, are referred to using their full title.

Other abbreviations

AL1 Andrew Louth (1996)

AL2 Andrew Louth (2003)

BDEC Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Parry et al., 1999)

C&C Refers to the tabulation of versions of the Philokalia provided by Conticello and Citterio, 2002

DB David Balfour (1982)

DS Refers to the entry on the Philokalia in Dictionnaire de Spiritualité (K. Ware, 1984)

EGP English translation of the Greek Philokalia (Palmer et al., 1979, 1981, 1984, 1995)

IH Irénée Hausherr (1978)

LTN Letter to Nicolas

MEC A Monk of the Eastern Church (1987)

NCE New Catholic Encyclopedia (Mcdonald et al., 1981)

NGP Notes by Nikodimos in the Greek Philokalia (Andrew Louth, personal communication)

No. Number

NRSV New Revised Standard Version

ODCC Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Cross and Livingstone, 1997)

OTSL On the Spiritual Law

RBW Righteous by Works

Ref Reference

TR Theophan the Recluse. Biographical notes from the Dobrotolubiye (Kadloubovsky and Palmer, 1979)

Vol Volume Number

References to the Philokalia

Where possible, references to works in the Philokalia are given citing the name of the author, the name of the work (using the abbreviated title in Appendix 1) and the paragraph number (preceded by #), followed by the volume and page references to the English translation in brackets. For example:

Mark the Ascetic in On the Spiritual Law, #85 (EGP 1, 116)

Where paragraph numbers are not provided (e.g. in the works of Peter of Damaskos), the name of the author and the titles of the work and portion of the work are given, followed by volume and page references to the English translation in brackets. For example:

Peter of Damaskos in Book II in VI. Hope (EGP 3, 227)

As sheep to a good shepherd, the Lord has given to man intellections of this present world.

Evagrios of Pontus

Texts on Discrimination, #16 (EGP 1, 48)

Thoughts, like sheep, given the chance, are prone to wander aimlessly. Sheep follow one another, without any necessary sense of direction or purpose. They are often found gathered together in flocks, but each individual creature presents its own image of vulnerability and individuality. They get lost, and become sick or lame or hungry. But they can also be shepherded, thus gaining direction, and may be cared for, fed, and protected. A good shepherd will search out the lost, feed the hungry and care for the sick.

Such an image, particularly for those familiar with rural life, offers countless metaphorical and parabolic possibilities. Thus, most famously in the Christian tradition, Jesus is the good shepherd and we are the sheep of his pasture.1 Evagrios of Pontus (345/346-399), however, suggests that we are all shepherds and that God has given us thoughts – or here “intellections” – as sheep to be cared for.

It is a much neglected, and somewhat disconcerting, facet of the extended metaphor of sheep and shepherd, at least in relation to the New Testament of Christian scripture, that the sheep are, at the end of the day, there for the shepherd, or for the one whom the shepherd serves, and not primarily the other way around. In ancient times, as now, sheep were kept for their wool and lambs for meat. Then, although less commonly now, lambs were killed for sacrifice. Unless they are the victims of sickness, or of marauding wolves, sheep and lambs are eventually put to death. Perhaps this reality betrays an intended irony when the Jesus of John’s gospel expresses his willingness to lay down his life for his sheep? However, returning to the metaphor of thoughts as sheep that human beings shepherd in their minds, can we say that these sheep are there for the benefit of those who think them, or for those whom the thinker serves, rather than for their own sake?

The answer to this question will depend upon theology and philosophy for it could well be argued, amongst other things, that the thoughts are simply there for no purpose or that they are there for the benefit of those who think them, or that they are ultimately there for the glory of God. Perhaps it is a little more helpful, however, to ask what the purpose might be of shepherding these thoughts? Surely most people shepherd their thoughts with a purpose in mind? That purpose might be to serve their own advantage, or to serve the benefit of others, or to serve God, or perhaps it might be for some other purpose. However, the fact is that we do shepherd our thoughts and that we perceive ourselves as doing so for a reason. No matter how much they wander randomly, become sick, follow the wrong leader, or otherwise misbehave, it is a feature of the inner life of human beings that we do keep trying to shepherd our thoughts in particular ways with particular purposes in mind. The writing and the reading of this text are but one example of this amongst an infinite number of possible examples that could be taken from the thoughts that humans have, whether communicated in speech or writing or remaining secret within our own minds and souls.

Furthermore, the shepherding of thoughts is something which we perceive as uniquely and characteristically human and as deeply intimate. To talk about the ways in which we shepherd thoughts within our own inner space is to talk about something which gets to the heart of what it means to be human and also – at the individual level – to the heart of what it means to be “me”. Thoughts are very personal and yet, because they wander like sheep, going to places to which we perhaps wish they hadn’t gone, we may be ashamed of them and not want other people to know about them. Undoubtedly most of us, most of the time, only share with others those thoughts that we feel pleased with, or at least which are not embarrassing. We talk about the ones that are shepherded in ways that we think others will approve of, but not about the ones that get lost, or the ones that we took to prohibited places. Our conversation about the shepherding of our thoughts, if not the actual business of shepherding, is strongly determined by a sense of what is socially acceptable.

In a post-Freudian world, we are aware that much of what we “think” is unconscious and that the unconscious world – of which we are generally not explicitly aware, but about which we are generally uneasy – has characteristic ways of making itself felt: in dreams, in slips of the tongue, in humour and so on. Indeed, so familiar are we now with this concept that we feel less ashamed than we used to of confessing thoughts that Freud has led us to believe we need not be ashamed about. Or, at least, we are less ashamed of some such thoughts some of the time, for we now seem to spend much more time in western society talking about sex, but much less time talking about death, for example.

Applying this Freudian knowledge to our metaphor of thoughts as sheep and ourselves as shepherds, we might say that we don’t always know where our sheep have gone, but we are often vaguely aware that there are some missing. Or else we might be more ready to admit pasturing sheep in some places than in others. But, still, the process of tending this flock is very important to us and we spend much – if not all – of our waking life giving it our attention.

Where, then, does this extended metaphor take us?

It is used here primarily for two reasons. Firstly, it facilitates an introduction to talking about why our inner world is important to us as human beings and yet why we also often do not speak about it. Secondly, however, the quotation with which it began is taken from one of the earlier contributions to a collection of texts known as the Philokalia – an anthology of spiritual writings from the Eastern Christian tradition, spanning the fourth to the fifteenth centuries C.E.

Philokalia means literally “love of the beautiful”, but is usually understood in Greek as referring to an anthology of works.2 Today, reference to the Philokalia is usually taken, unless specified otherwise, to denote a particular anthology assembled by two Greek monks in the eighteenth century, which was first published in Venice in 1782.3 The compilers, Nikodimos of Mount Athos (1749-1809) and Makarios of Corinth (1731-1805) apparently chose their texts with a view to making more widely available that which would be helpful in the spiritual life, drawn from the hesychastic tradition. This tradition, broadly understood, seeks to find an inner stillness of the soul – away from the distractions of thoughts and desires – within which contemplation of God might be undertaken and, eventually, union with God found. In other words, it is a tradition of Christian prayer which emphasises attention to the inner life, the life of thoughts, with a view to the purpose of contemplating God himself. To quote from another contributor to the Philokalia, Maximos the Confessor, and following the same metaphor used by Evagrios, within this tradition: ‘sheep represent thoughts pastured by the intellect on the mountains of contemplation’.4

The intention here, then, is to explore the ways in which this collection of texts might help with the process of shepherding thoughts or, to be less allegorical, the ways in which the tradition expressed within this collection of texts might assist in developing a Christian understanding of the inner life of thoughts and of nurturing mental well-being. Necessarily, this exploration does not confine itself to the inner life – the Philokalia talks of virtue in Christian living and not only of thoughts and desires. However, it does emphasise the life of prayer as the only basis on which Christians can properly understand the inner life or conceive of mental well-being. It thus assumes from the outset that the central, primary and underlying purpose for which Christians will properly and beneficially shepherd their thoughts is that of loving, serving and worshipping God. It also assumes that the shepherding of thoughts for other purposes – such as human happiness as an end in itself – will always be more or less unsatisfactory. However, whilst these are fairly major assumptions, which atheist shepherds of thoughts such as Freud would undoubtedly disagree with, it is not intended that they should hide this exploration away from a critical encounter with other shepherds and other traditions. On the contrary, such encounters are exactly what is intended here.

These assumptions do recognise, however, that complete objectivity is not attainable, either in the inner life or in academic discourse. An observer must occupy a particular position in order to observe and an awareness of the subjectivity of the space which one occupies is, it is contended here, not a weakness but rather a strength. There may, then, be other reasons for my use of the metaphor of sheep and shepherd as an introduction to this work. In fact, perhaps there is a necessity – rather than merely the possibility – of other reasons for my beginning in this way. If I approach this work from an academic perspective, I must also necessarily approach it as an exploration of my own inner world from within the Christian tradition to which I belong. This will surely reveal that there must be other reasons for my choice of this particular metaphor – reasons which are either concerned with my own conscious sense of vocation to be a shepherd of thoughts, or else perhaps my own unconscious thoughts around this theme (the “sheep” that I am only vaguely aware have “gone missing” from the fold of my consciousness). Perhaps – as I hope – these reasons concern my sense of purpose in combining a vocation to the priesthood with a training in clinical psychiatry and academic study, all of which seem to me to have this theme in common. Or perhaps – although I consciously deny it – they concern an attempt to find connections where there are none, to cover up the aimlessness of the mental wandering of my own thoughts like lost sheep. The point is not so much that either of these reasons is necessarily correct as that there are various possible reasons which are more concerned with the subjectivity of my vocation to write than the actual purpose of writing this particular text for others to read.

This subjectivity of writing is not eliminable from this text, but neither is it entirely unhelpful. Because of it, I approach the Philokalia with a view to being challenged by its discourse as to the ways in which my own thoughts may better be shepherded. If I do not allow the texts of the Philokalia to challenge me in this and other ways, as I also myself challenge them with a spirit of critical academic enquiry, the encounter is false. Indeed, to talk about a subject such as this and to remain entirely unaffected, or to avoid altogether any examination of its impact upon the understanding of one’s own thoughts, would seem rather dishonest. This is, after all, itself primarily an attempt to shepherd thoughts for a particular purpose – that of understanding better how the inner life may be understood and developed. Although the circularity of this process might seem to some to be undermining of objectivity, it is the reality of the process in which the compilers and authors of the Philokalia themselves engaged and in which they invite us to join them. Whilst I will not be uncritical of these fellow authors, I trust that I will show enough respect to take seriously what they have said to me.

I have wondered (my thoughts wandering like lost sheep perhaps?) what other metaphors might have been used to introduce this subject. As much of the writing was undertaken on Holy Island, in Northumberland, I looked across the beach and saw rocks scattered across the sea shore like sheep scattered across a pasture. I considered my own walks across these beaches and the way in which one’s attention is divided between an intended destination across the beach and the immediate task of finding a firm footing for one’s next step. It is easy to go astray from the former goal because of the necessity of the latter task. Rocks on the beach, like thoughts in the mind, are necessary as a basis for moving forward, but can easily also lead away from the place to which one intended to travel. But the need to find a firm footing does not invalidate the destination or refute the evidence of the eyes. It speaks only to human limitation.

Do such images assist in the examination of a subject which, since Freud, has become the subject of a vast and diverse technical literature? The possible answers to that question will be left for later consideration, but an unprejudiced examination of a pre-Freudian and pre-modern literature and the wisdom that it contains cannot avoid examining the possibility that they do assist in reaching a final destination; whereas, perhaps, the more technical tools of our contemporary academic discourse may confine themselves more to finding the next rock on which to stand.

The writers of the Philokalia sought a final destination by means of taking individual steps with care. To the best of my ability I have sought to follow that example in my writing on this subject. This book may therefore be considered as comprising six steps towards the goal of understanding what the Philokalia has to tell us about mental well-being and the shepherding of thoughts. These steps are:

1. In Chapter One I give consideration to influences that have helped to shape the writing of the Philokalia, its compilation, its teachings on the inner life of thoughts, and the foundations upon which it has been built. I do not feel that the teaching of the Philokalia on the inner life can be properly appreciated without this contextual information.

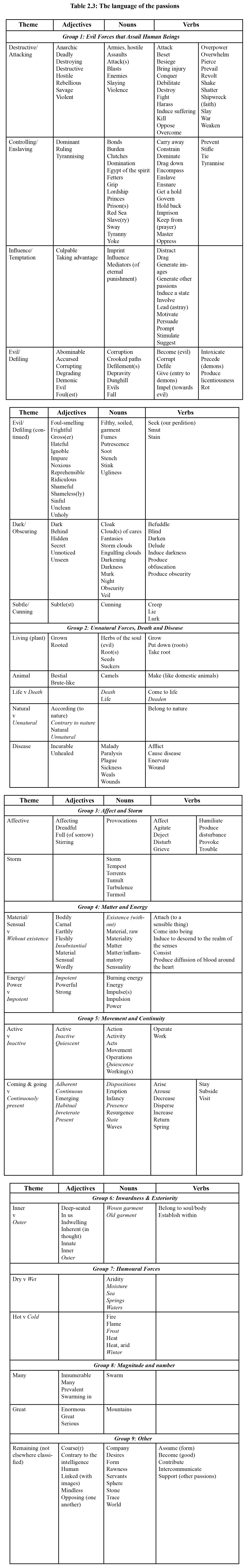

2. In Chapter Two, I focus on the teaching of the Philokalia on thoughts of a particularly troublesome kind, which the Philokalia refers to as “passions”. I have started here partly because this is such a central theme of the Philokalia, but also because it is where human beings start in trying to order their thoughts. It is a study in the unruliness of human thoughts, their tendency to go astray, and the nature of the challenge that they present to those who wish to shepherd them.

3. In Chapter Three, my controlling metaphor turns from rural life to the world of medicine, and I consider the remedies for the passions that the Philokalia prescribes.

4. Chapter Four might be considered a glance towards my final destination, rather than a step forward. However, if it is a step forward, it is the step of understanding how the Philokalia conceives mental well-being. In the medical terms of the previous chapter, it is concerned with better understanding health in order to be better equipped to treat the disease of the passions.

5. Chapter Five steps aside from the Philokalia in order to give consideration to the contemporary world of psychotherapy. What is psychotherapy, how does it conceive mental well-being, and what does it aim to achieve? The possibility of understanding the as providing a kind of psychotherapy is then considered. This raises questions about the nature of the soul, or self, and human concerns with inwardness and reflexivity.

6. Chapter Six attempts to explore the relationship between thoughts and prayer. When the Philokalia is consulted as a source of reference on thoughts, or the inner life, it always turns the focus onto prayer. When it is consulted as a source of guidance on prayer, it turns the reader’s attention towards a careful examination of their thoughts. This relationship therefore seems to be central to the Philokalia. It is studied here with reference to the preceding discussion on psychotherapy, and also by way of a brief exploratory engagement with some other western strands of thought, on philosophy (Paul Ricoeur on hermeneutics) and spirituality (Denys Turner and The Darkness of God).

In the Epilogue, reflecting briefly on the steps that have been taken, we shall return to the theme of shepherding thoughts and ponder where our journey has taken us.

I will close this introduction with one final quotation from the Philokalia on the theme of sheep and shepherds, this time from Ilias the Presbyter:

Where fear does not lead the way, thoughts will be in a state of confusion, like sheep that have no shepherd. Where fear leads the way or goes with them, they will be under control and in good order within the fold. Fear is the son of faith and the shepherd of the commandments. He who is without faith will not be found worthy to be a sheep of the Lord’s pasture.5

Here, then, is the question to be addressed. How does the Philokalia teach us that we can control and order thoughts that are confused, difficult to control and in disorder?

1: Influences and Foundations

Explorations of the inner world of human beings might reasonably be expected to be dependent upon the outer world in which they live: its culture, its history, traditions, assumptions, language and beliefs. Such things influence the way in which we perceive ourselves and thus, at least potentially, the way in which we think. If we are to understand properly what the authors and compilers of the Philokalia had to say about the inner life it would therefore seem to be important to consider the nature of their outer world, and especially its anthropological assumptions and beliefs. However, this immediately presents a problem, for the Philokalia is the work of about 40 authors, and two compilers, whose lives span well over a thousand years. Can anything be said about “their world” which might go beyond vague generalities or spurious over-generalisations?

It might be tempting to emphasise the importance of tradition to Byzantine civilisation and Orthodox Christianity as reason for expecting continuity of fundamental assumptions across even a thousand years and more of writing. However, it has famously been suggested that “to represent Byzantium as immutable over a period of eleven centuries is to fall into a trap set by Byzantium itself”.1 We must also remember that, during the period in question, some very significant events took place – not least the seven universally agreed ecumenical church councils and the great schism of 1054. The doctrinal, and especially the Christological, controversies that raged during this period variously affect different works within the Philokalia. For example, one work attributed to Neilos the Ascetic in the original Greek Philokalia is now known to have been by Evagrios of Pontus (345/346-399), but transmitted under the name of Neilos because of the tainting of reputation of Evagrios by his association with Origenist heresy. Almost at the other end of the chronological span of the Philokalia, the writings of Gregory Palamas (1296-1359) show evidence of his concern to defend the hesychast tradition itself from its critics. Maximos the Confessor (580-662), the single biggest contributor of texts, was exiled and tortured for his defence of the doctrine of the divine and human wills in Christ, in keeping with the Council of Chalcedon. He was only vindicated at the 6th Ecumenical Council, almost 20 years after his death. The historical contexts and doctrinal preoccupations that emerge from place to place within the Philokalia are thus varied indeed, and in some places represent fierce controversies of their time.

In an introduction to the English translation of the Philokalia, the translators and editors suggest that there is an inner unity to the Philokalia which is conferred more than anything by recurrent reference to invocation of the name of Jesus (or the Jesus Prayer as it is now known). They argue that this is “one of the central forms of the art and science which constitute hesychasm” and that this is evident even in some of the earliest texts.2 It is again tempting to draw from this a reassurance as to common underlying assumptions within the Philokalia, but that would certainly be premature. The Jesus Prayer is but one theme amongst many to be found in these texts and it is hardly clear that it is a major theme in the earlier texts, even if it might be argued that evidence of it is to be found in them. It would seem in any case unlikely that a tradition of spirituality dating back to the fourth century would not have undergone at least some changes in emphasis and development of ideas – especially in view of the vicissitudes of its history. Thus, for example, the later texts would seem to show evidence of the influence of the Syrian spirituality introduced in the thirteenth/fourteenth century revival, an influence which exerts its own distinctive emphasis on these later texts.

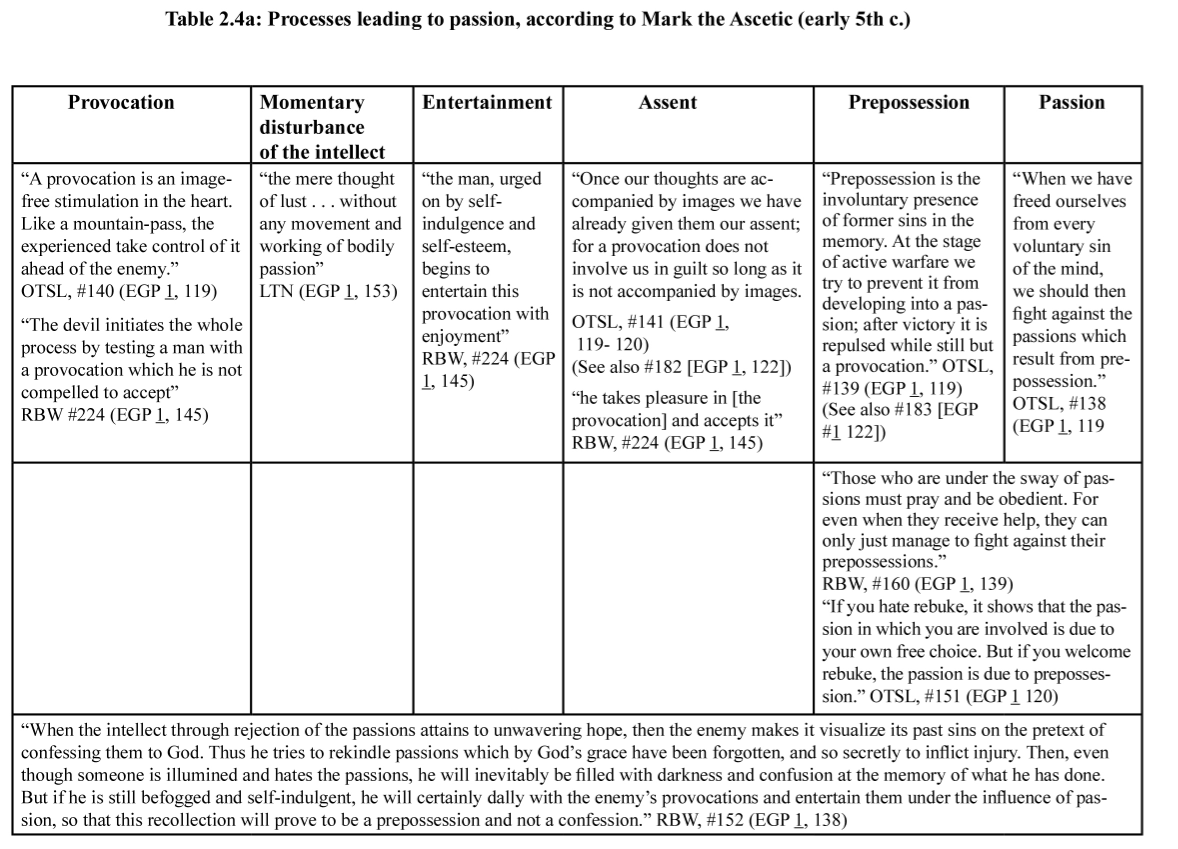

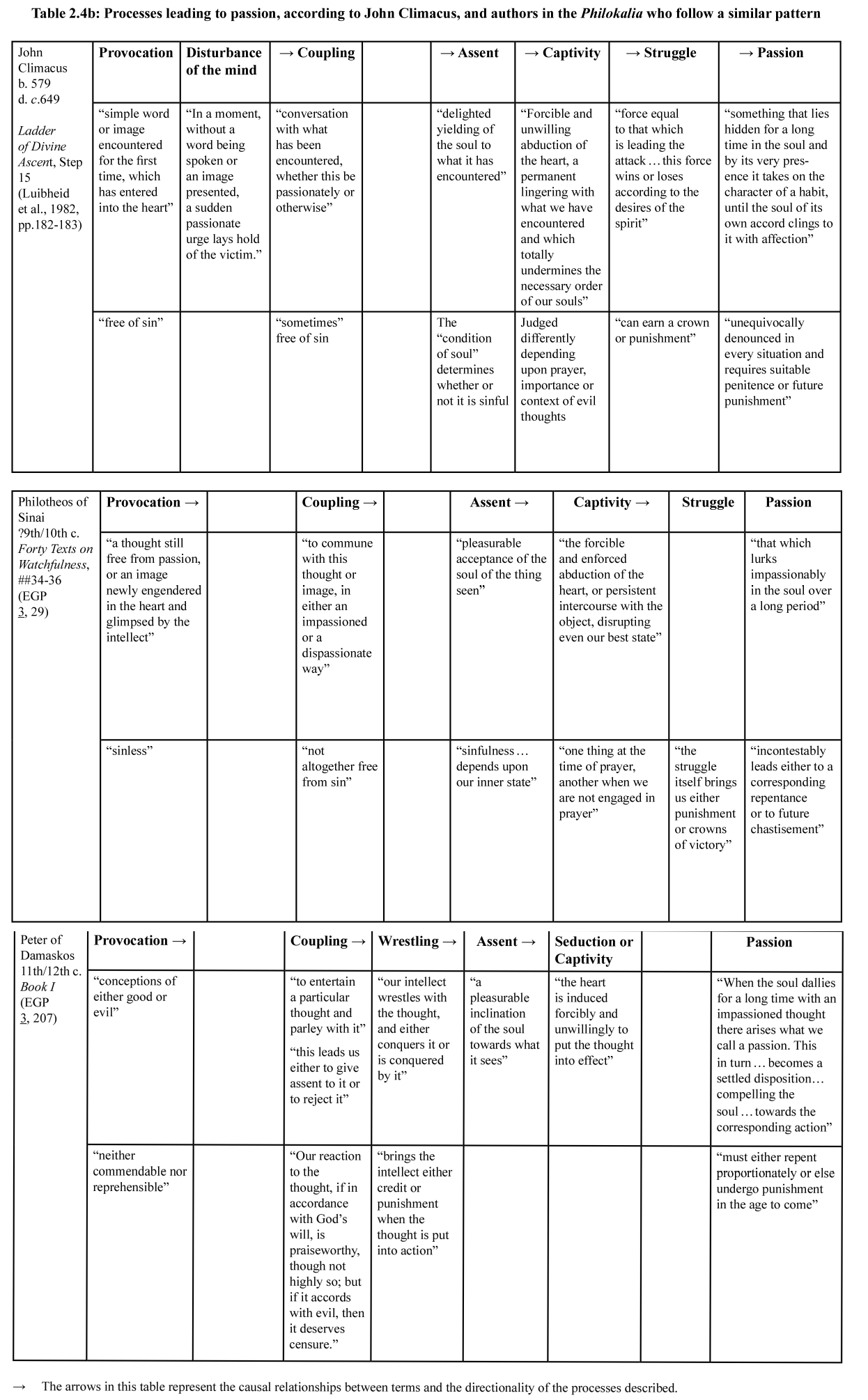

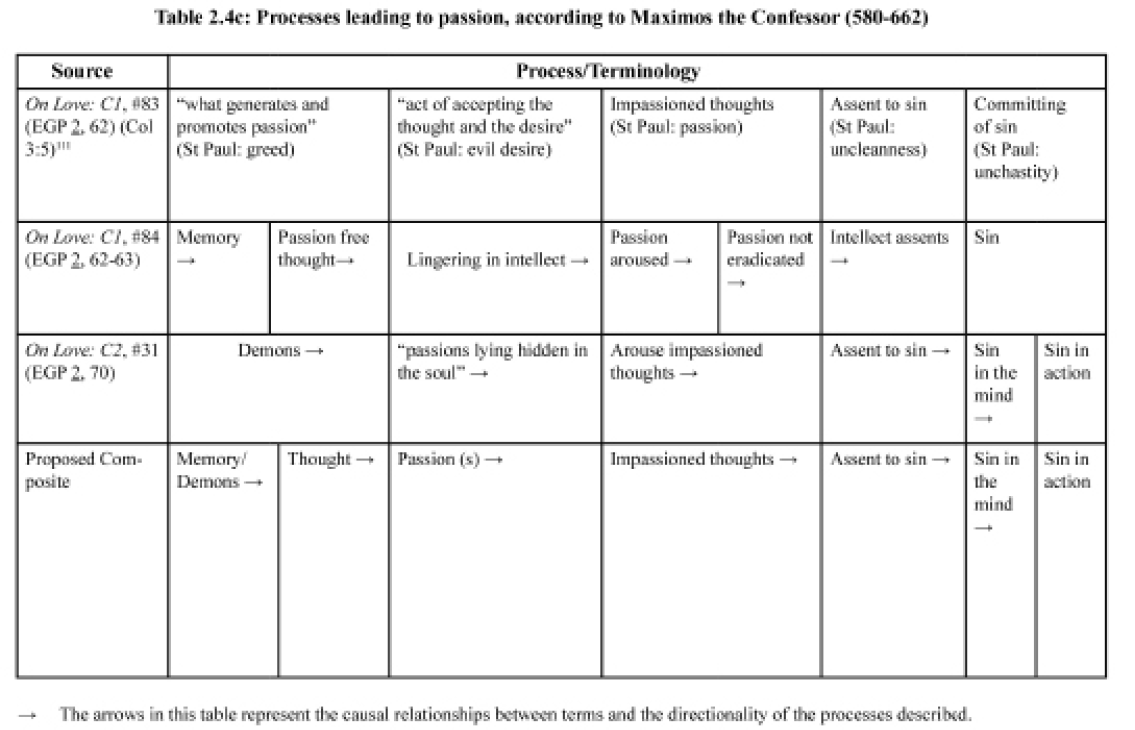

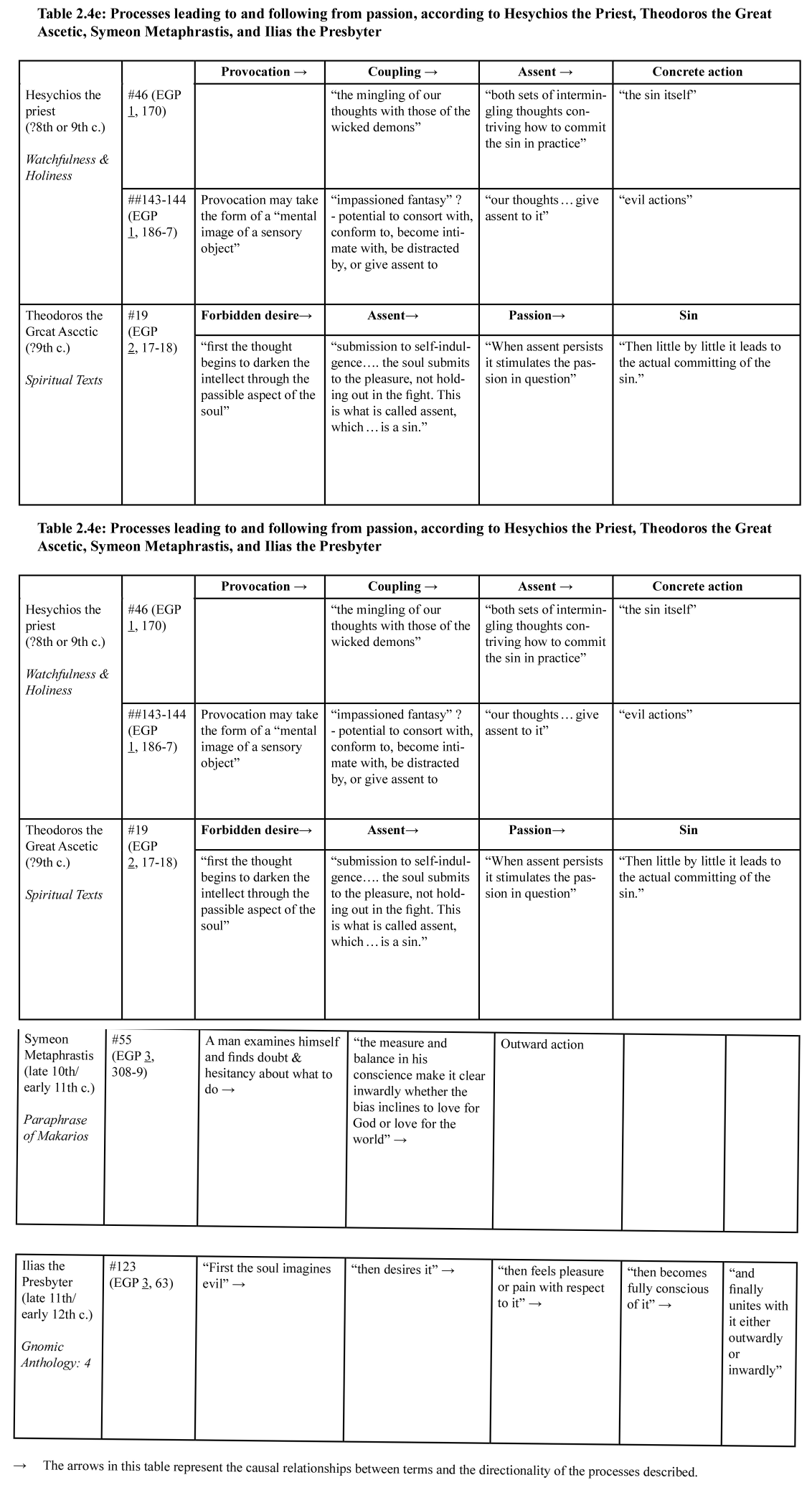

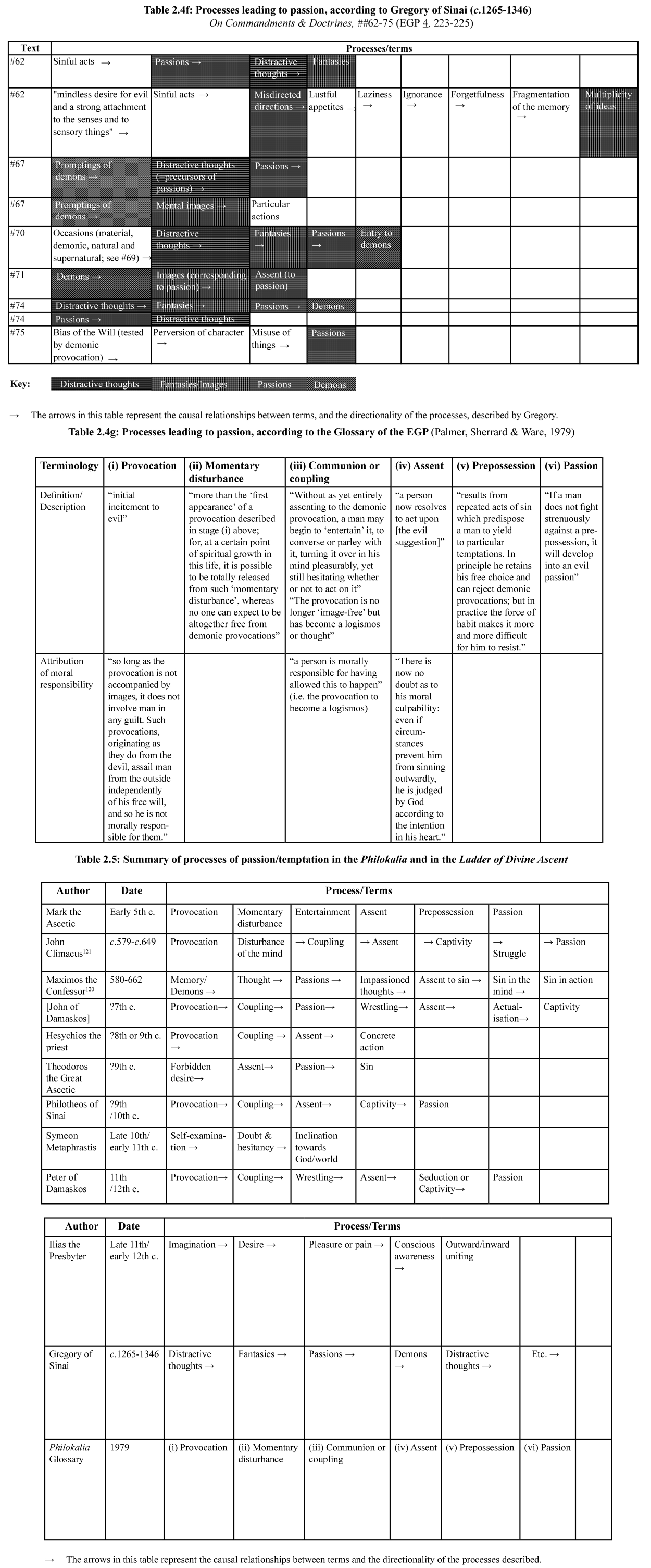

A glossary provided in the English translation to the Philokalia also implies that there is a consistency of terminology throughout its span of writings. There is no doubt that this glossary provides helpful clarification for the reader who is new to the Philokalia and its world of thought, and that there is a terminology with which a reader gradually becomes familiar when reading and re-reading the Philokalia. However, greater familiarity begins to suggest that the appearance of consistency is almost as much confusing as it is helpful. Thus, for example, the glossary helpfully points out that even such a fundamental term as “passion” refers on the part of some writers to something intrinsically evil, but on the part of others to something fundamentally good, something which may be redeemed.3 Again, the helpful analysis of the process of temptation4 refers to various sources, both from within the Philokalia itself and also John Climacus’s Ladder of Divine Ascent, but careful study of these sources shows a heterogeneity of understandings, albeit with some core terms (such as “provocation” or “assent”) which are used more or less consistently.

It is not, however, necessary to be completely nihilistic as to the possibility of grasping something of an understanding of the common assumptions that have formed the understanding of life in the inner world that is such a central theme of the Philokalia. Firstly, there have been historical, philosophical and theological influences, which appear to have provided something of an enduring source of reference to its authors. Secondly, there is evidence of internal consistency in regard to certain significant fundamental assumptions and themes – of which the Jesus Prayer is but one.

It would therefore appear helpful here to give some further consideration to the following:

1. The compilation and history of the Philokalia as an anthology of texts

2. The anthropology of the Philokalia

3. The tradition of the Desert Fathers

4. The work of Evagrios of Pontus

5. The use of scripture by the authors of the Philokalia

To some extent these might be considered as external influences that helped to shape the Philokalia, but to some extent (especially in the case of Evagrios) they are internal to its fabric. They are therefore considered together here, partly as formative external influences and partly as foundational stones upon which the Philokalia was erected.

1. Compilation, Translation and Evolution of the Philokalia

The hesychastic tradition, from within which the Philokalia emerged, has a long history. From as early as the fourth century C.E. the term “hesychia” was used by Christian monastic writers to refer to a state of inner quietness to be achieved in prayer as preparation for communion with God. From the sixth to the eleventh centuries in the Byzantine world a “hesychast” was simply a monk or ascetic, and hesychasm referred simply to a broadly contemplative approach to prayer. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries there was something of a spiritual revival, centred on Mount Athos, in which Gregory of Sinai (1258-1346) and Gregory Palamas took a leading role. This gave birth to a movement now known as the “Hesychast Tradition”, which drew upon traditions of Christian spirituality both from Syria and the Egyptian desert fathers.

The hesychastic tradition came under fierce attack in the fourteenth century, primarily because of an assertion that prayer of the heart can lead to a vision of Divine Light; a light which, it was asserted, can be seen even in this life, and by human eyes in a literal physical sense. This light, it was further asserted, is identical to that which surrounded Christ on Mount Tabor in his transfiguration. Gregory Palamas, a contributor to the Philokalia, was a leading – and eventually successful – defender of the tradition against these attacks. Hesychasm was formally adopted at the Councils of Constantinople (1341, 1347 and 1351) and subsequently became an accepted part of Orthodox spiritual tradition.5

The compilation and dissemination of the Philokalia in the eighteenth century represented a significant component of a renaissance of the hesychastic tradition.6 The Philokalia was compiled by Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and Makarios of Corinth, both of whom belonged to the spiritual renewal movement of the “Kollyvades”. This movement was traditional and conservative, critical of liberal teaching of the enlightenment, and enthusiastic for the spirituality and theology of the Fathers of the Eastern Church. However, Nikodimos at least was not so conservative as to prevent his drawing upon western sources in his own writings.7

Makarios was born in 1731 in Corinth and was named Michael at his baptism. He was educated in Corinth and eventually became a teacher there himself. In 1764 the Archbishop of Corinth died, and Michael was elected his successor. In 1765, in Constantinople, he was ordained Archbishop and renamed Makarios. As Archbishop he began a series of reforms, including prohibition of clergy from holding political office, and measures to ensure that the clergy were properly educated. The outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war in 1768 forced Makarios to leave Corinth and although peace was restored in 1774 another Archbishop was appointed in his place and he never resumed his position there. In 1783 Makarios anonymously published Concerning Frequent Communion of the Divine Mysteries, in which he argued the case of the Kollyvades in favour of more frequent reception of communion than the two or three times each year that had become customary. The book was hastily condemned by the Ecumenical Patriarch but later (in 1789) approved and recommended by a new Patriarch. The last years of his life, from 1790 to 1805, were spent almost entirely in a hermitage on Chios where, according to Cavarnos, he “[subjected] himself to severe ascetic struggle, practicing interior prayer, writing books, confessing and counselling people, instructing them in the true Faith, inciting them to virtue, and offering material help to those in need”.8

Nikodimos was born in 1749 on Naxos, one of the Aegean islands. He was educated initially on Naxos, and from the age of 15 years at Smyrna, where he learnt Latin, Italian and French. In 1775 he went to Mount Athos and became a monk. It was in 1777 that Makarios visited Athos and gave him the task of editing the Philokalia, and also two other works,9 although in fact the two men had first met some years earlier on the island of Hydra. Nikodimos went on to become a prolific author, editor and translator of other theological works.10 Nikodimos’ last years were spent in writing, and it is as an author, translator and compiler that his life most stands out. However, there is also no reason to doubt the testimony that he practiced mental prayer assiduously throughout his 34 years on Mount Athos.11 It would not seem unreasonable to speculate that his introduction to the Philokalia by Makarios in 1777 exerted a lifelong influence upon him.

Clearly the selection of texts for inclusion in the Philokalia is a very significant matter, but we know surprisingly little about how the selection was made. Constantine Cavarnos first reports a traditional view that it was compiled by monks on Mount Athos in the fourteenth century, but then goes on to assert that Makarios himself was the real compiler.12 Certainly it is clear that Makarios was the more senior editor and that the initiative for the work came from him and not from Nikodimos.13 We might speculate that the selection was not actually made by Nikodimos and Makarios, but rather already existed in some way as a collection of texts revered by tradition, or else already assembled by earlier compilers. Alternatively, Ware has suggested, there may have been a policy of including rare or unpublished texts.14

We do know that the texts were drawn from the libraries of Mount Athos. The introduction by Nikodimos refers to “manuscripts which had been lying inglorious and motheaten in holes and corners and darkness, cast aside and scattered here and there”.15 In this introduction, Nikodimos also describes the purpose of the Philokalia as being the provision of a “mystical school” of mental (or “inward”) prayer16:

This book is a treasury of inner wakefulness, the safeguard of the mind, the mystical school of mental prayer…. an excellent compendium of practical spiritual science, the unerring guide of contemplation, the Paradise of the Fathers, the golden chain of the virtues…. the frequent converse with Jesus, the clarion for recalling Grace, and in a word, the very instrument of theosis.”17

The full title of the original Greek Philokalia is:

The Philokalia of the Neptic Saints gathered from our holy Theophoric [“God-bearing”] Fathers, through which, by means of the philosophy of ascetic practice and contemplation, the intellect is purified, illumined, and made perfect.18

The English translators of the Philokalia, commenting on the title and subtitle, suggest that it is through “love of the beautiful” that the intellect is “purified, illumined and made perfect”, and that it was this purpose of purification, illumination and perfection that governed the choice of texts.19 The texts of the Philokalia are thus, they argue, “guides to the practice of the contemplative life”.20

Kallistos Ware,21 one of the English translators of the Philokalia, has suggested that reflection on its contents enables us to deduce something about its scope, its aim and the means that it recommends to those who wish to achieve its aim. The scope of the Philokalia he understands as being defined by its focus on the inner life, characterised especially by the concepts of nepsis (watchfulness) and hesychia (stillness). The aim of the Philokalia he identifies as deification. The means to this end he identifies as being a life of unceasing prayer from the depths of the heart, exclusive of all images and thoughts, in which the name of Jesus is invoked, and in which particular physical techniques (see, for example, Chapter 3, p.147) may or may not be employed.

Ware further suggests that the spirituality that emerges from the Philokalia has four characteristics:

1. A predominant influence of Evagrios and Maximos

2. A basic antinomy between the knowability and unknowability, the immanence and transcendence, of God which might be regarded as “Palamite”, although preceding the time of Gregory Palamas

3. An absence of western influence

4. A relevance to all Christians

Whilst questions remain about exactly what guided the inclusion and exclusion of particular texts, the overall thrust of the Philokalia would therefore seem fairly clear. This is an anthology of eastern Christian texts designed to assist in the inner life of prayer.

All the texts included in the Philokalia by Nikodimos and Makarios were originally written in Greek, except for two by John Cassian, which were translated from Latin into Greek during the Byzantine period. We may count 62 texts included in the Philokalia (see Appendix 1).22

The authors were undoubtedly all men (although the actual authorship of some texts remains in dispute) and all belonged to the monastic tradition. Cassian is the only “western” author included. The single biggest contributor was Maximos the Confessor, followed by Peter of Damaskos. About some of the authors we know much; about others, however, we know little or nothing with any certainty. We may calculate that there were approximately 40 or more authors in all (see Appendix 2). Attributions of authorship of some texts in the original Greek edition are now known to be incorrect. In several cases we know that contributions were made to particular texts by two or more authors.

The Philokalia, as a compilation of the original Greek texts, prepared by Makarios and Nikodimos, with an overall introduction and with notes to introduce the texts associated with each author, was published in a single volume in Venice in 1782 at the expense of John Mavrogordatos, Prince of Moldo-Wallachia.23 A second edition was produced in Athens in 1893, including some additional texts by Patriarch Kallistos. A third edition was produced in five volumes, also in Athens, in 1957-1963.24

The first translation of the Philokalia, into Slavonic, was made by Paisius Velichkovsky (1722-1794),25 and was published in Moscow in 1793 under the title Dobrotolubiye and under the sponsorship of Metropolitan Gabriel.26 Velichkovsky was a Ukrainian monk who lived on Mount Athos from 1746-1763. He was later abbot of large monasteries at Dragomirna (1763-1775) and Niamets (1779-1794) in Romania and was the initiator of a spiritual renaissance there within the hesychastic tradition.

During his time on Mount Athos, Velichkovsky developed a concern to find, copy, collect and translate patristic texts. Initially this seems to have arisen out of an inability to find a suitable spiritual instructor (or starets). Starchestvo (or eldership) was a key element in the hesychastic tradition.27 However, as Velichkovsky was unable to find someone suitable as his own starets, he seems to have turned to patristic writings as an alternative source of instruction.28 The concern for patristic texts that he acquired in this way early in life continued during his later life as an abbot in Romania, by which time he seems to have had literally hundreds of monks working on the tasks of copying and translation.

Velichkovsky’s Dobrotolubiye was not a complete translation of the Greek Philokalia. Only 27 of the 62 works comprising the latter were included in copies of the first edition, although a few additional texts by Patriarch Kallistos were included.29 A second edition was published in 1822 (almost 30 years after Velichkovsy’s death). A further 13 works from the Greek Philokalia were included in the second edition and in at least some copies of the first edition.30

It is clear that Velichkovsky’s interest in patristic works was one that he shared with the compilers of the Greek Philokalia and also that he knew of their interest. In a letter of uncertain date to Archimandrite Theodosius of Sophroniev, Velichkovsky wrote of Makarios’ fervour and care in the process of seeking out and copying patristic books on Mount Athos, a process that led to the publication of the Philokalia.31 It is also clear that Velichkovksy’s interest in these texts predated by many years the assignment by Makarios to Nikodimos in 1777 of the task of compiling and editing the Greek Philokalia. Whether we may accept the conclusion of the editors of the biography of Velichkovsky (written by his disciple Schema-monk Metrophanes) that in fact it was Velichkovsky who imparted to Makarios the knowledge of what to look for, the purpose of the search, and awareness of the value of the texts would seem much more debatable.32 However, it is clear that Velichkovsky’s translation work began very many years before the Philokalia was published in 1782. We might speculate that a loose collection of texts existed prior to the interests of both Velichkovsky and Makarios.

Subsequently, the Philokalia was translated into Russian. There are widespread references in the literature to an alleged Russian translation by Ignatii Brianchaninov (1807-1876), published in 1857.33 However, according to Kallistos Ware it would seem that this translation does not in fact exist.34 A Russian translation by Theophan the Recluse (1815-1894) was published in Moscow from 1877-1889 in five volumes, also under the title Dobrotolubiye.

Theophan35 studied at Kiev Academy and entered monastic orders in 1837. After two months he was ordained priest and subsequently became a schoolteacher. Like Makarios, he demonstrated an openness to western scholarship and was widely read. In 1850 he was appointed as a member of the Russian Official Commission to Jerusalem. In the course of this work he travelled widely and was able to visit a series of ancient libraries, which he found to be neglected and unappreciated. He developed a knowledge of French, Arabic, Greek and Hebrew which enabled him to read and catalogue the rare manuscripts that he found. It would seem that it was at this stage in his life that he developed an interest in early ascetic Christian literature.

In 1859 Theophan became Bishop of Tambov, and then in 1863 Bishop of Vladimir. In 1866 he became Prior of Vysha monastery. Three months later he was released from his responsibilities as superior in order to become a recluse and in 1872 he entered almost complete seclusion. During his time in seclusion Theophan engaged in a prolific correspondence and also published a number of important works, including Unseen Warfare (a revision and translation of an earlier Greek translation of Lorenzo Scupoli’s Spiritual Combat and Path to Paradise made by Nikodimos) and the Russian Dobrotolubiye.

Theophan’s Dobrotolubiye represented a considerable expansion of the Greek Philokalia, from 1,200 to 3,000 pages, published in five volumes.36 Whilst it included a number of additions not to be found in the Greek Philokalia it also omitted a number of texts.37

The Philokalia was later translated into Romanian by Father Dumitru Stăniloae (1903-1993), and published between 1946 and 1991 in twelve volumes under the title Filocalia sau culegere din scrierile sfintsilor Parintsi. The additions to the Romanian Filocalia are even more numerous and extensive.38

Stăniloae was born and lived his whole life in Romania but received theological education in Athens and Munich. He became a professor of theology in Bucharest and published 90 books, 275 theological articles and numerous other translations, reviews, lectures and other items over a period of some 60 years.39 Stăniloae had a particular interest in the works of Gregory Palamas. Along with many other clergy, he was imprisoned from 1958 to 1963 by the communist authorities as a political criminal. Four volumes of his translation of the Philokalia, based on the first two volumes of the Greek Philokalia, were published prior to this imprisonment, during the period 1946 to 1948. The fifth volume did not appear until 1976. However, after the translation of the Greek Philokalia was completed (with the publication of the eighth volume in 1979)40 Stăniloae continued to work on four more volumes, incorporating works by a number of authors not included in the original Greek version.41

Modern translations of the Greek texts of the Philokalia have also appeared in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Finnish and Arabic, and the Greek text may now be consulted in a modern fifth edition.42

If our speculation that a loose collection of texts already existed prior to 1777 is correct, then the apparently free additions of texts to Russian and Romanian translations might be taken to suggest something of a living tradition. Within this tradition, additions to a core Philokalia were apparently either not considered inappropriate, or else were thought necessary because of unavailability of the supporting texts that would originally have been found alongside the Philokalia in the library of Mount Athos.43

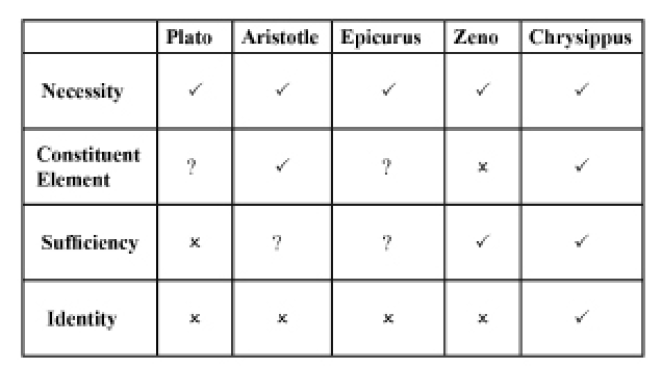

2. Anthropology

In his Republic, Plato (c.347-247 B.C.E.) argues for a tripartite understanding of the human soul or mind (yuch,).44 Both in the course of Plato’s argument, and also in our own experience, two of these elements are easier to understand than the third. All three are more akin to motives than to “parts” in any anatomical sense. The first is reason, a reflective and rational element (logistiko,n). The second is irrational appetite (evpiqumhtiko,n) – which includes desires such as hunger, thirst and sexual drive, orientated towards satisfaction and pleasure. The third (qumiko,n), including apparently varied motives such as anger, indignation, ambition and a sense of what is “in the heart”, the so-called “incensive” power, might be translated “spirited” – although the use of such a theologically loaded word in the present context would inevitably be confusing. For Plato, the immortal soul was understood as being imprisoned, during this life, in its physical body.

The Platonic understanding of the soul has been very influential upon Christianity in general, and in particular the tripartite model of the soul appears to have influenced the Philokalia, almost from beginning to end. However, before we give consideration to this in more detail, it is important to say something about the relationship between body and soul.

The Philokalia not infrequently, but perhaps mainly in its earlier texts, refers to an apparently tripartite model of human beings, usually as body, soul and spirit, or as body, soul and intellect. Thus, for example, in the text attributed to Antony the Great (but probably actually of Stoic origin), and placed as the first text in the original Greek Philokalia, we find:

Life is the union and conjuncture between intellect, soul and body, while death is not the destruction of these elements so conjoined, but the dissolution of their inter-relationship; for they are all saved through and in God, even after this dissolution.45

Again, in Evagrios:

Let the virtues of the body lead you to those of the soul; and the virtues of the soul to those of the spirit; and these, in turn, to immaterial and principial knowledge.46

However, this impression of a tripartite anthropology appears to be either unrepresentative or illusory as there seem to be many more references to human beings as simply body and soul (or, sometimes, body and intellect47), and it is clear that this is because the spirit, or intellect, is seen as being merely a part of the soul. Thus, for example, in the aforementioned text attributed to Antony we find:

The body, when it is united with the soul, comes from the darkness of the womb into the light. But the soul, when it is united with the body, is bound up in the body’s darkness. Therefore we must hate and discipline the body as an enemy that fights against the soul.48

In fact, although it was clearly believed by the original compilers to be an authentic work of Antony, the English translators of the Philokalia have placed this work in an appendix on the basis that there is no evidence of Christian authorship, but rather that it appears to be a collection of Stoic and Platonic texts written between the first and fourth centuries C.E. (The negative Platonic view of the soul as imprisoned in the body is clearly evident here.) However, the understanding of human beings as body and soul seems to provide the generally pervading anthropology of the Philokalia, and the tension between the body and soul is often evident. For example, in Theoretikon, [Theodoros the Great Ascetic] writes:

What, then, is the nature of our contest in this world? The intelligent soul is conjoined with an animal-like body, which has its being from the earth and gravitates downwards. It is so mixed with the body that though they are total opposites they form a single being. Without change or confusion in either of them, and with each acting in accordance with its nature, they compose a single person, or hypostasis, with two complete natures. In this composite two-natured being, man, each of his natures functions in accordance with its own particular powers. It is characteristic of the body to desire what is akin to it. This longing for what is akin to them is natural to created beings, since indeed their existence depends on the intercourse of like with like, and on their enjoyment of material things through the senses. Then, being heavy, the body welcomes relaxation. These things are proper and desirable for our animal-like nature. But to the intelligent soul, as an intellective entity, what is natural and desirable is the realm of intelligible realities and its enjoyment of them in the manner characteristic of it. Before and above all what is characteristic of the intellect is an intense longing for God. It desires to enjoy Him and other intelligible realities, though it cannot do this without encountering obstacles. 49

Elsewhere, the tension between body and soul is even more marked, as in the reference by Theognostos to “war between body and soul”,50 or else more positively construed, as in Peter of Damaskos:

We should marvel, too, at how the body, that is not its own animating principle, is, at God’s command, commixed with the noetic and deiform soul, created by the Holy Spirit breathing life into it (cf. Gen. 2:7).51

Here, and in other places,52 the relationship between body and soul is seen as parallel to that between God and human beings. God/soul provides the “animating principle” or life to that which would otherwise be inanimate or lifeless. Similarly, in Gregory Palamas, the divine quality of the soul, albeit set in contrast to the material nature of the body, is emphasised in the context of the doctrine of creation:

So great was the honour and providential care which God bestowed upon man that He brought the entire sensible world into being before him and for his sake. The kingdom of heaven was prepared for him from the foundation of the world (cf. Matt. 25:34); God first took counsel concerning him, and then he was fashioned by God’s hand and according to the image of God (cf. Gen. 1:26-27). God did not form the whole of man from matter and from the elements of this sensible world, as He did the other animals. He formed only man’s body from these materials; but man’s soul He took from things supracelestial or, rather, it came from God Himself when mysteriously He breathed life into man (cf. Gen. 2:7). The human soul is something great and wondrous, superior to the entire world; it overlooks the universe and has all things in its care; it is capable of knowing and receiving God, and more than anything else has the capacity of manifesting the sublime magnificence of the Master-Craftsman. Not only capable of receiving God and His grace through ascetic struggle, it is also able to be united in Him in a single hypostasis.53

This vision of the divine soul in union with a physical body created by God is in tension, however, with the condition of the soul and body as they exist after “the fall”. Thus, Gregory of Sinai writes:

When God through His life-giving breath created the soul deiform and intellective, He did not implant in it anger and desire that are animal-like. But He did endow it with a power of longing and aspiration, as well as with a courage responsive to divine love. Similarly when God formed the body He did not originally implant in it instinctual anger and desire. It was only afterwards, through the fall, that it was invested with these characteristics that have rendered it mortal, corruptible and animal-like. For the body, even though susceptive of corruption, was created, as theologians will tell us, free from corruption, and that is how it will be resurrected. In the same way the soul when originally created was dispassionate. But soul and body have both been denied, commingled as they are through the natural law of mutual interpenetration and exchange. The soul has acquired the qualities of the passions or, rather, of the demons; and the body, passing under the sway of corruption because of its fallen state, has become akin to instinct-driven animals. The powers of body and soul have merged together and have produced a single animal, driven impulsively and mindlessly by anger and desire. That is how man has sunk to the level of animals, as Scripture testifies, and has become like them in every respect (cf. Ps. 49:20).54

Much of what the Philokalia has to tell us about the inner life depends upon this basic anthropology of body and soul created by God in union with each other, but also in tension with each other; fundamentally good, but also fundamentally distorted and corrupted by the fall. Whilst, as we have seen already, there are variations in emphasis amongst different contributors to the Philokalia, which is only as one would expect, this basic understanding seems to pervade the texts. Sometimes the emphasis is more on the goodness of creation, sometimes more on its corruption as a result of the sin of Adam. The sense of tension between body and soul, and within the soul, is however more or less ubiquitous.

As for the soul itself, the tripartite Platonic model is adopted throughout, almost completely without any deviation or dissent.55 In English translation, these parts are usually rendered as the “intellect” or “intelligence”, the “desiring” or “appetitive” power, and the “incensive” power. The latter two are often referred to as the “passible”, or irrational, aspects of the soul, implying greater vulnerability to passion (pa,qoj – about which, more later). However, this does not imply that the intellect or intelligence is not also susceptible to passion, and the passions are sometimes classified according to which of these three parts of the soul they primarily affect.

At this point, various clarifications are required, for things are not quite as simple as has been portrayed so far. In particular, the nature and terminology of Plato’s “rational” element of the soul, as understood by the authors of the Philokalia, requires some further elaboration. According to the glossary in the English translation of the Philokalia, this part of the soul is to be referred to as the “intelligent” (logistiko,n) aspect or “intelligence” (logiko,n). However, in practice, the authors of the Philokalia often also refer to it as the “intellect” (nou/j).56 Furthermore, both of these terms are clearly distinguished from “reason” (dia,noia), a term which is never used by authors of the Philokalia as a name for this part of the soul.57

Reason is clearly distinguished from intellect and intelligence. As the translators and editors of the English edition make clear in their glossary, it is:

the discursive, conceptualizing and logical faculty in man, the function of which is to draw conclusions or formulate concepts deriving from data provided either by revelation or spiritual knowledge (q.v.) or by sense-observation. The knowledge of the reason is consequently of a lower order than spiritual knowledge (q.v.) and does not imply any direct apprehension or perception of the inner essences or principles (q.v.) of created beings, still less of divine truth itself. Indeed, such apprehension or perception, which is the function of the intellect (q.v.), is beyond the scope of the reason.58

This becomes clear in, for example, usage of the term by Ilias the Presbyter:

By means of intellection the intellect attains spiritual realities; through thought the reason grasps what is rational. Sense-perception is involved with practical and material realities by means of the fantasy.59

The intellect, however, is described in the English glossary as the “highest faculty” possessed by human beings, through which they may perceive spiritual realities. Rather than operating through use of rational or abstract processes, it discerns Divine truth by direct experience or “intuition”. It is the means by which human beings may engage in contemplation.60

In distinction from this, the Greek root of the word for intelligence betrays its even closer association with Divine reality – with the L,ogoj himself. It is used with reference to the possession of spiritual knowledge. It is the “ruling aspect” of the intellect.61

Thus, for example, Maximos the Confessor writes, in Various Texts: C2:

Every intellect girded with divine authority possesses three powers as its counselors and ministers. First, there is the intelligence. It is intelligence which gives birth to that faith, founded upon spiritual knowledge, whereby the intellect learns that God is always present in an unutterable way, and through which it grasps, with the aid of hope, things of the future as though they were present. Second, there is desire. It is desire which generates that divine love through which the intellect, when of its own free will it aspires to pure divinity, is wedded in an indissoluble manner to this aspiration. Third, there is the incensive power. It is with this power that the intellect cleaves to divine peace and concentrates its desire on divine love. Every intellect possesses these three powers, and they cooperate with it in order to purge evil and to establish and sustain holiness.62

Here, intelligence, desire and the incensive power represent the three powers of the intellect, where “intellect” appears effectively to be synonymous with “soul”.63 Elsewhere, the intellect is distinguished from the soul,64 or else described as being in various other relationships to it. It is referred to as being in the depths of the soul,65 as being the “eye of the soul”,66 as being “the pilot of the soul”,67 as being “consubstantial” with the soul,68 the illumination of the soul,69 and as capable of being united with the soul.70 The relationship is therefore not a simple one, and the descriptions of it, at least in the Philokalia, do not appear to be entirely consistent.

The place of intelligence, however, is to restrain the intellect and the passions,71 to contemplate virtue,72 and to cleave to God himself.73 But this purpose can only be fully understood in the context of the incarnation of the Lo,goj who has created, and re-created, all things, including the human logiko,n:

The Logos of God, having taken flesh and given our nature subsistence in Himself, becoming perfect man, entirely free from sin, has as perfect God refashioned our nature and made it divine. As Logos of the primal Intellect and God, He has united Himself to our intelligence, giving it wings so that it may conceive divine, exalted thoughts. Because He is fire, He has with true divine fire steeled the incensive power of the soul against hostile passions and demons. Aspiration of all intelligent being and slaker of all desire, He has in His deep-seated love dilated the appetitive aspect of the soul so that it can partake of the blessings of eternal life. Having thus renewed the whole man in Himself, He restores it in an act of re-creation that leaves no grounds for any reproach against the Creator-Logos.74

The Platonic tripartite model of the soul is thus very much in evidence in the Philokalia, but it is also clear that it has been utilised for a Christian purpose – that of understanding the inner life of human beings in the context of the incarnation of God in Christ.

3. The Desert Fathers

For three centuries Christians suffered persecution. At first (until about 64 C.E.) this was at the hands of Jewish authorities, then at the hands of the Roman empire. Christianity seems widely to have been disapproved of in the Roman world, and Christians were referred to as “atheists” because of their failure to believe in the Roman gods. At times this disapproval was associated with mob violence. Successive emperors and governments made it a capital offence to be a Christian, banished Christians, confiscated their property, sent them into the arena to fight as gladiators, tortured and imprisoned them. Churches and copies of scripture were burned. Periods of respite were brief, until in 311 Galerius, Caesar of the east, issued an Edict of Toleration. Although his successor Maximinus attempted to counteract this edict, his efforts were largely ineffective and in 313 he also issued notices of toleration. Emperors in the west, first Maxentius and then Constantine, followed suit and in 313 the latter drew up an edict of toleration similar to that of Galerius.75

It is perhaps hard for many Christians today to imagine what it must have been like to live, and die, under the persecution experienced by Christians during these first three centuries, although it is also easy to exaggerate. For example, persecution of Christians in Russia in the twentieth century might arguably have been much worse. Nonetheless, many died, and some renounced their faith. Many, but not all, lived on the social edges of society. For them, the injunction of Jesus that they should deny themselves and take up their crosses and follow him can hardly have seemed metaphorical.76 It would seem also that such Christian communities lived in eager anticipation of the expected return of Christ. In this context, there is evidence that from the early third century C.E. onwards some Christians, although at this stage they should not be considered to have adopted a “monastic” life, deliberately chose a poor, celibate and ascetic lifestyle in order that they may devote themselves more fully to their Christian vocation as they understood it.77

At the beginning of the fourth century C.E., with the edicts of toleration, and then the adoption of Christianity by Constantine, everything changed. Christianity was now a legal and acceptable part of the fabric of society. Undoubtedly, many Christians found this difficult to accommodate. Increasingly, some – perhaps many – chose to retreat into the deserts of Syria, Palestine, and especially Egypt, where they could devote themselves to prayerful waiting for the return of Christ.78 One contemporary account states:

One can see them in the desert waiting for Christ as loyal sons watching for their father…. There is only the expectation of the coming of Christ in the singing of hymns…. There is no town or village in Egypt and the Thebaid which is not surrounded by hermitages as if by walls.79

Many of these Christians lived as solitary hermits – perhaps most famously Antony of Egypt, whose subsequently highly influential life was written by Athanasius.80 Others lived in coenobitic communities, and from this developed a Christian tradition of monasticism which eventually, at least partly through the influence of John Cassian (c.365-c.433), had an important influence upon the whole western European monastic tradition.81

Amongst the desert hermits, coenobites and monks of the fourth and fifth centuries C.E., there developed a focus on the inner life – upon the presence of sin in the human heart, the need for forgiveness, virtue in human living, and prayer. Many, perhaps most, of these Christians were not learned. Their focus was upon a simple, practical, life of prayer and certainly not on writing or academic study. Indeed, the impression is sometimes given that writing and study were positively frowned upon.82 However, various kinds of literature did emerge from this tradition.83 In particular, there are the “Lives” of various saints (especially that of Antony of Egypt by Athanasius, c.355-362), accounts of travels to the Egyptian desert (especially the Lausiac History, c.419/420, and the History of the Monks of Egypt, c.394/395), various kinds of instructional literature (notably that by Evagrios and Cassian), and letters from various authors (including seven by Antony of Egypt and 14 by Ammonas). The pinnacle of traditional monastic literature, however, is to be found in the sayings, proverbs and anecdotes of those who lived in the Egyptian desert, which were recorded, edited and passed on. Collections of these sayings appeared in the late fifth century and in the sixth century, which are now known as the “Sayings of the Desert Fathers” or the Apophthegmata Patrum.84

The life of the Desert Fathers was severe. They lived in small huts or caves and undertook basic manual work such as rope or basket making. They ate and drank extremely little, they forsook sleep in favour of prayer and, of course, they gave up the possibilities of marriage and family life. Renouncing of material possessions was a fundamental step, and most did not even have a copy of the Bible, but would rely for prayer and meditation on such passages as they had committed to memory. Most of their time would be spent alone, and remaining alone in ones cell was often emphasised as being of fundamental importance to the spiritual life. 85

Sayings that have been handed down frequently take the form of a question – usually posed by a visitor or by a more junior brother to an older and wiser “Abba” or, in some cases, “Amma”. The responses given to such questions vary between the obscure, profound, apparently rude, and extremely harsh. Because they are usually located in particular circumstances, many of which were not be recorded, different sayings can also appear contradictory of each other. However, they also reflect extreme humility, compassion, wisdom and, at least sometimes, humour.

In some ways, the Philokalia and the sayings of the Desert Fathers are worlds apart. A five-volume anthology hardly compares with a largely oral tradition that had a suspicion of books and learning. However, possession of the Philokalia potentially avoids the need to own, or have access to, a large library.86 Some of the “centuries” of texts in the Philokalia also have a literary quality about them which is not dissimilar to that of the Apophthegmata Patrum. They have similar ascetic concerns, they both appear to be intended as a basis for prayer and living, rather than academic study, and they employ a not dissimilar terminology of the inner life of thought and prayer and virtue.

Thus, for example, we might compare Abba Theonas and Hesychios the Priest on prayer and the passions:

Abba Theonas said, “When we turn our spirit from the contemplation of God, we become the slaves of carnal passions.”87

Whereas, in Watchfulness & Holiness by Hesychios, we find:

Contemplation and spiritual knowledge are indeed the guides and agents of the ascetic life; for when the mind is raised up by them it becomes indifferent to sensual pleasures and to other material attractions, regarding them as worthless.88

Such common ground should, of course, not be surprising. Apart from the general observation that the Desert Fathers might be considered the founders of Christian monasticism or, if this is debated, at least that they influenced its subsequent course very considerably, and that the Philokalia emerged from that same monastic tradition, there are also more direct links to be found.

At least three of the earlier authors of the Philokalia had in fact lived in the Egyptian desert themselves. Isaiah the Solitary was probably not the contemporary of Makarios of Egypt that Nikodimos considered him to be, but probably did live at Sketis in Egypt in the fifth century C.E., before moving to Palestine, and therefore can be said to represent firsthand experience of the tradition of the Desert Fathers.89 Evagrios of Pontus went to Egypt in 383 C.E. and spent the remaining 16 years of his life first at Nitria and then at Kellia. During this time he was a disciple of Makarios the Great (also known as Makarios of Egypt) and also had contact with Makarios of Alexandria.90 John Cassian lived in Egypt from c.385/6 to 399, during which time he was a disciple of Evagrios. He subsequently travelled to Constantinople and then spent the remainder of his life in the west. He founded two monasteries in Marseilles and wrote two books, The Institutes and The Conferences, based upon his experiences in the Egyptian desert, abbreviated parts of which are included in the Philokalia.91 Although between them these three authors contribute a little less than a third of only the first volume of the Philokalia, they are the first three books in the English translation and are the earliest contributors.

In addition to Isaiah, Evagrios and Cassian, it seems likely that Mark the Ascetic also spent some time living as a hermit in the desert, although in fact we know very little about him.92 The Philokalia also includes a paraphrase by Symeon Metaphrastis of homilies that purport to be by Makarios the Great, whose sayings feature prominently in the Apophthegmata Patrum. However, it would now seem highly unlikely that Makarios was in fact the author of these homilies.93 Similarly, it is of note that the opening work of the original Greek Philokalia was one attributed to Antony the Great. Although this is now known not to have been written by Antony of Egypt, it would seem reasonable to assume that it may have suited the compilers of the Philokalia very well to place first in their work a text by this most famous of the Desert Fathers.

In addition to the contributions to the Philokalia by those who had firsthand experience of the desert tradition, it is clear that there is a more pervasive influence. For example, Peter of Damaskos (whose works effectively provide a “mini-Philokalia” within the Philokalia) quotes the Desert Fathers some 30 times,94 and Nikiphoros the Monk quotes from the lives of a number of the Desert Fathers in Watchfulness & Guarding.95 The Desert Fathers also exerted an indirect influence on writers such as Maximos the Confessor, the single largest contributor to the Philokalia, although this is not always explicitly acknowledged.96 But perhaps the most important direct and indirect influence comes from the perceptiveness of Evagrios of Pontus. There can be little doubt that his spirituality and psychology influenced all the subsequent writers whose works were included in the Philokalia.97 It is therefore to Evagrios that we must turn next.

4. Evagrios of Pontus

If you are a theologian, you will pray truly; and if you pray truly, you will be a theologian.98

Evagrios was born in Pontus, in Cappadocia, but moved in 379 to Constantinople where he studied under Gregory Nazianzen.99 By this time he was possibly already a monk. Although, up until this time, he appears to have shown much promise as a theologian, he left the city in 382 having begun an affair, albeit perhaps unconsummated, with the wife of a prominent local figure. Fleeing to Jerusalem he came close to abandoning his monastic vocation altogether, but was persuaded not to by Melania the Elder, a prominent Roman widow and foundress of a double monastery. Perhaps also with her encouragement, Evagrios left Jerusalem in 383 for the Egyptian desert, where he was to remain (apart from brief excursions to Alexandria and elsewhere) until his death.

Evagrios spent his first two years in Egypt in the desert at Nitria, one of the major monastic centres of the time. He then retired to the even more remote centre of Kellia, where he became a pupil of Makarios the Great, one of the most famous of the Desert Fathers. During his time here he subjected himself to a severe regime, which probably damaged his health. He would sleep only four hours each night, walking back and forth and keeping himself occupied in order to remain awake during the day. When subject to sexual temptation he once spent an entire night in mid-winter praying naked standing in a cistern of water.100 He ate only once a day, and then only very limited foods.

He remained at Kellia until his death in c.399. During this time he became a respected teacher and, unusually, also the author of a series of important works. Amongst these were instructions on the monastic life (The Foundations of Monastic Life: A Presentation of the Practice of Stillness,101 and The Monk: A treatise on the Practical Life102), numerous commentaries on scripture (including Scholia on Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job, and Psalms), various letters and most importantly for the present purpose some works on prayer and the inner life (Chapters on Prayer103, On the Eight Thoughts,104 On Thoughts105, Antirrhetikos, Gnostikos, and the Kephalaia Gnostica). Some of these works106 survive only in Latin, Armenian or Syriac translation.

During his lifetime, Evagrios remained a respected theologian and teacher on the spiritual life. After his death, as the works of Origen were increasingly scrutinised and condemned as heretical, Evagrios’ reputation began to suffer by association. Despite this, his works were widely circulated and translated into Latin, Coptic, Syriac, Arabic and various other languages. Eventually, Origen was condemned at the Second Ecumenical Council in 553, as were a series of beliefs held by Evagrios, and many copies of his works were subsequently destroyed.107 Despite this, Evagrios’ insights into prayer, the inner life and asceticism were still widely appreciated and were read and developed by others. That it was possible that this could happen was partly because his so-called theological works were separated from his ascetic and spiritual works, partly because of wide dissemination and translation, and also because some works were transmitted under other names (as indeed originally happened with one of his contributions to the Philokalia).

i. Foundations

Taught by Makarios, Evagrios shared with the Desert Fathers a belief that inner stillness, hesychia, was facilitated by avoiding frequent or inappropriate social contacts, or any other external circumstances which might provide unnecessary agitation or distraction.108 In Foundations he sets out the basics: celibacy, poverty, a frugal diet, living either alone or with like-minded brothers in the desert, avoidance of cities, infrequent contact with family and friends, undertaking basic manual labour so as not to be a burden on others, but avoidance of buying and selling where at all possible, and sleeping little and only on the ground. All these matters were, however, merely preliminary. His real concern was with the inner world of thoughts and it is here that he showed himself to be highly psychologically insightful and original. These “foundations” of the monastic life are put in place in order to attain and preserve an inner state of “stillness”109 (h`suci,a) and this in turn is preparatory to other things, which he deals with in his other works.

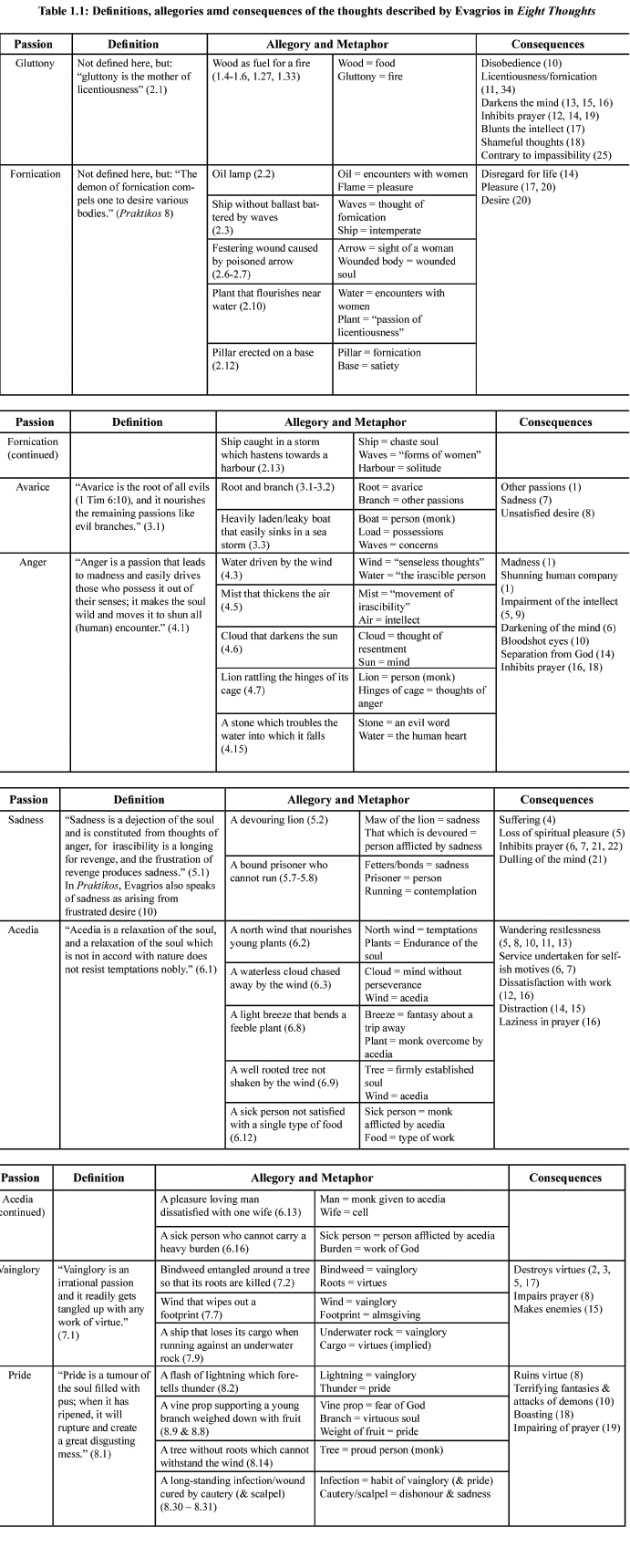

ii. Eight Thoughts

In Eight Thoughts, Evagrios deals in turn with eight thoughts, or kinds of thoughts, each of which presents to the Christian a point of potential struggle or temptation. The material is presented as a series of brief paragraphs, often only one sentence long, under each heading. These paragraphs take the form of proverbs, aphorisms, or wise sayings, or else admonitions and instructions. Allegory and metaphor are used liberally. Reference to, and quotation of, scripture is used to illustrate and justify, but some whole sections of the discourse (specifically on fornication and acedia) do not explicitly refer to scripture at all. Whilst the texts have a certain quality reminiscent of the sayings of the Desert Fathers, and presumably must have been derived, at least in part, from the same underlying oral tradition, the Fathers are not explicitly quoted. The texts appear to be offered for contemplation and reflection – to be prayed over and lived out rather than studied systematically in an academic fashion. One is left with the impression that they arise in turn from Evagrios’ own reflections, and those of his mentors.

The list, which appears elsewhere in Evagrian work and is original to Evagrios, has been highly influential upon other authors – including authors of the Philokalia. Elsewhere, Evagrios states that “All the generic types of thoughts fall into [these] eight categories in which every sort of thought is included.”110 The list comprises the following:

1. Gluttony

2. Fornication

3. Avarice

4. Anger

5. Sadness

6. Acedia

7. Vainglory

8. Pride

The title of this work refers to these items as being “thoughts”, but in other works (e.g. On the Vices opposed to the Virtues) they are referred to as vices, and in each case there is at least some reference here to an opposing virtue. In places the thoughts are also referred to as “passions” (e.g. Gluttony, #3; Fornication, #12; Avarice, #1). In other works (e.g. Praktikos), but interestingly not here, Evagrios refers to demons using the same names.