Resistance in the army initially coalesced around Oberst (later Generalmajor) Henning von Tresckow, who was Chief of Operations, Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Centre). He tried to persuade the new commander of Army Group Centre, Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge, to join the conspiracy, but Kluge was ambivalent. Indeed, in October 1942, Kluge accepted a large payment from the Führer for his good conduct, which made it difficult for him to act against his benefactor. But if Kluge would not act, others would. Already in February 1943 a number of senior officers in Heeresgruppe B (Army Group B) planned to arrest Hitler when he visited Poltava in the Ukraine.4 It was recognized that there would be resistance from his security personnel and, as such, the conspirators were prepared, if necessary, to kill Hitler then and there. However, instead of flying to Poltava as planned, Hitler flew to Saporoshe and the plan was scrapped.

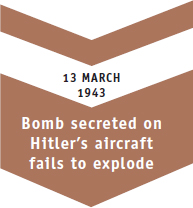

The difficulties of arresting and killing Hitler were now very apparent and it was understood that a more effective method of removing him was needed. The conspirators hit on the idea of planting a bomb on Hitler’s aircraft and detonating it while he was airborne. This would not only kill their nemesis but had the added benefit of potentially deflecting blame away from the army. A plan was developed and, on 13 March 1943, two British Clam mines disguised as a Cointreau bottle were smuggled onto Hitler’s plane by Oberleutnant Fabian von Schlabrendorff, one of Tresckow’s co-conspirators. The detonator was activated, but the device did not go off. Hitler landed safely and the conspirators had to recover the bomb. Seemingly the extreme cold in the hold meant that the detonator did not activate the explosives. The so-called Smolensk Attentat (attempted assassination) had failed.

A week later, on 21 March, a further opportunity presented itself at the Heldengedenktag (Heroes’ Memorial Day) in Berlin. Oberst Rudolf-Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff of the staff of Army Group Centre planned to plant a bomb in the hall where Hitler was due to give a speech. He reconnoitred the room, but security was tight (following Johann Georg Elser’s unsuccessful attempt in Munich on 8 November 1939) and there was no opportunity to hide the bomb, let alone get to it again to prime the detonator. Recognizing that this approach was not feasible, Gersdorff now considered an alternative. He would strap explosives to himself and detonate them after Hitler’s speech when he visited the exhibition of captured equipment. For this he ideally needed an instantaneous fuse, but none could be sourced in the time available, so he used a timed fuse. Hitler completed his speech and headed for the exhibition. Gersdorff set the timer running, but Hitler fairly galloped through the exhibits and was gone. The assassin could only remove the timer and deposit it down the toilet before the explosives were detonated.

In the first half of 1943 four failed attempts had been made on Hitler’s life. But if the conspirators were depressed about their lack of success they were equally perturbed by the parlous state of the war by late 1943. The Wehrmacht had suffered defeats in North Africa and, significantly, at Stalingrad, and Italy signed an armistice with the Western Allies in September 1943. Importantly, in January 1943 the Allies met at Casablanca and agreed a policy of unconditional surrender. Kluge, Generalfeldmarschall Georg von Küchler, the commander of Heeresgruppe Nord (Army Group North), and Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein, commander of Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South), now signalled their support for action, but it only extended as far as representations to Hitler to end the war. However, nothing was done and, in October 1943, Kluge was injured in a car crash; this potential figurehead for the resistance was thereby removed from the equation – at least in the short term.

In spite of this setback a further unsuccessful attempt on Hitler’s life was made in December 1943. Hauptmann Axel Freiherr von dem Bussche-Streithorst, one of Tresckow’s co-conspirators, again planned a suicide attack using a bomb with a hand-grenade fuse to detonate it. Hitler was due to attend an exhibition of uniforms and military equipment and, while he was there, Bussche would embrace the Führer and kill them both. However, the exhibition was postponed and Bussche had to return to the front. Another officer offered to take his place when the exhibition was rearranged but again the show was postponed.

Finally, on 11 March 1944, Rittmeister Eberhard von Breitenbuch, aide-de-camp to Generalfeldmarschall Ernst Busch, the new commander of Army Group Centre, came to the Berghof, the Führer’s residence near Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps, on the pretext of briefing Hitler, but secretly planning to shoot him dead. Armed with a pistol he prepared to meet the Führer, but was refused entry and the attempt was cancelled.

The failure of the various assassination attempts coincided with a series of setbacks for the resistance. Firstly, the Abwehr, so long a haven for resistance, was dissolved. In 1943 the Gestapo raided Oster’s department and he was dismissed from his post that April; in February 1944 Canaris was also dismissed and the Abwehr was merged with the Sicherheitsdienst (the SS Intelligence agency). Secondly, the leader of the so-called Kreisau Circle,5 Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, was arrested by the Gestapo in January 1944 along with a number of other members, thus eliminating another centre of resistance.

Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg with co-conspirator Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim (on the right). The photograph was taken in the summer of 1942 at OKH headquarters in Vinnitsa, in the Ukraine. Two years later they were again side by side in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock facing a firing squad. (Topfoto)

Also in April 1943, one of the most able and determined members of the resistance was severely injured while serving in North Africa. Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was wounded in an air attack; he lost his left eye, his right hand was amputated above the wrist and he lost the ring and little fingers on his left. In spite of this, Stauffenberg’s desire to assassinate Hitler was undimmed, but to Stauffenberg’s co-conspirators his handicaps were considered so severe that he could not possibly be considered to carry out the assassination of Hitler. Moreover, after any attempt on Hitler’s life, Stauffenberg’s skills would be needed in Berlin to direct the coup. In the summer of 1943 the debate was academic at any rate, because Stauffenberg had no access to the Führer.

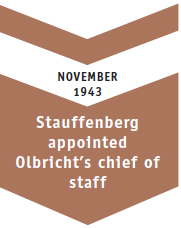

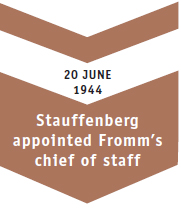

This changed first in November 1943, when Stauffenberg was made chief of staff to General der Infanterie (General of Infantry) Friedrich Olbricht, chief of the Allgemeines Heeresamt (General Army Office), and then in June 1944, when he was made chief of staff to Generaloberst Friedrich Fromm, the commander-in-chief of the Replacement Army. Ironically, the decision to appoint Stauffenberg was made by Hitler’s chief adjutant, Generalleutnant Rudolf Schmundt, one of the Führer’s most trusted advisors, who would be seriously injured by the bomb explosion on 20 July.

Almost immediately upon taking up his post, Stauffenberg explained to Fromm his intention to kill Hitler. Fromm greeted the news with indifference and neither the conversation nor Stauffenberg’s plan were ever mentioned again. With no explicit direction from his superior to abandon the idea, Stauffenberg continued with his preparations. British-made explosives, more powerful than anything produced in Germany, were sourced by Army Group Centre and were sent by courier to East Prussia, where they were secreted at Mauerwald, the location of OKH headquarters near to the Wolfsschanze. Normally, this would have been the ideal location, but because of building work, Hitler and his support staff were temporarily located at Berchtesgaden. In order to be available for any attempt the explosives had to be transported by train to Berlin, where they were delivered to Stauffenberg on 25 May. He now had the tools; he just needed the opportunity to use them.

Hitler visits Generalleutnant Rudolf Schmundt in hospital near the Wolfsschanze following the blast on 20 July. Schmundt was head of the Heerespersonalamt and initially made a good recovery, but died in October from complications arising from injuries suffered in the explosion. (Topfoto)

At the end of May Stauffenberg made his first trip to Berchtesgaden in preparation for a briefing to the Führer at the beginning of June. It is unclear if he believed that this first meeting would provide an opportunity to put his plan into action, not least because Oberst Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim, the man who had replaced Stauffenberg as Olbricht’s chief of staff and who would lead the coup in Berlin, was still on leave. Even so, fate intervened once again and, on 6 June 1944, the Western Allies landed in Normandy. Stauffenberg was now caught on the horns of a dilemma; with Germany fighting on two fronts, the end of the war was surely imminent and he therefore questioned whether there was any point in assassinating Hitler. Through an intermediary he asked Tresckow, who was still a leading light in the conspiracy despite his geographic separation, what he should do. Tresckow was categorical in his response: ‘The assassination of Hitler must take place … Even if it does not succeed, the coup d’état must be attempted. The point now is not the practical purpose, but to prove to the world and before history that the German resistance have staked their all and put their lives on the line…’ (quoted in Hoffmann 2008: 238).

His faith restored, Stauffenberg once again returned to his plans. These had to be matured quickly, as events in Germany and at the front were making an early strike imperative. Dr Julius Leber and Dr Adolf Reichwein, Socialist leaders who were close to Stauffenberg, had been arrested at the beginning of July along with a number of Communist leaders with whom they had met. By this time the Allies had consolidated their foothold in Normandy and the Soviets had launched their summer offensive on the Eastern Front on 22 June; in less than three weeks the Red Army had smashed through Army Group Centre, with 28 German divisions destroyed or captured.

Hitler, flanked by Stauffenberg (left), Puttkamer and Keitel (right), greets General der Flieger Karl-Heinrich Bodenschatz in front of the guest bunker at the Wolfsschanze on 15 July 1944. Of interest are the fake trees, which helped camouflage the headquarters from aerial observation. (Topfoto)

While the need to expedite any assassination plans was clear, the conspirators had to consider the potential fallout of any assassination attempt. Following Hitler’s death, who would be the natural successor? Would he be able to muster enough support to threaten or crush the coup? Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had fallen from favour, but he was still the anointed successor to Hitler. He was head of the Luftwaffe, which had flourished under the Nazis and was unquestionably the most loyal of the three services. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was another potential leader. He commanded the SS and, as such, was a powerful figure. The conspirators therefore agreed that Hitler, Göring and Himmler should be killed at the same time. This was logical, but impractical. Göring rarely turned up to military briefings and although Himmler did, his attendance was patchy. The consequences of this decision were soon to become apparent. Up to this point Stauffenberg believed that Generalmajor Helmuth Stieff would plant the explosives. He was a member of the resistance and, as head of the Organizational Section at OKH, he was in regular contact with the Führer.

On 7 July Stieff had an ideal opportunity to plant a bomb when, after much persuasion, Hitler agreed to attend a uniform and equipment exhibition at Klessheim, near Salzburg (the show that had been postponed from December 1943), but Stieff called off the attempt. The reason is unclear; he may have lost his nerve, or it may have been because Göring and Himmler were not present. Certainly this latter factor was the reason for the cancellation of the 11 July attempt. On this occasion Stauffenberg was due to be at Hitler’s briefing in the afternoon at the Berghof. However, in the morning Stauffenberg learned that the respective heads of the Luftwaffe and the SS would not be in attendance. Stieff hesitated once again and directed Stauffenberg to postpone the attempt, much to Stauffenberg’s displeasure. This proved to be the last opportunity at the Berghof. Three days later Hitler moved his headquarters back to the Wolfsschanze, even though the building work was incomplete. Any attempt on Hitler’s life would now have to be carried out at the Wolfsschanze.

4 Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South) was split into two army groups: A and B.

5 This group of German dissidents was centred on the Kreisau estate of Helmuth James Graf von Moltke.