On 15 July Fromm and Stauffenberg were ordered to travel to the Wolfsschanze to attend a series of briefings with Hitler; at one of these Stauffenberg planned to detonate his bomb. In Berlin, Mertz von Quirnheim placed the troops in the city on alert for Operation Valkyrie. This was done at 1100hrs, about the same time that Stauffenberg left for Rastenburg – a full six hours ahead of any assassination attempt. This suggests that Mertz von Quirnheim and Stauffenberg had already decided that Hitler must die, irrespective of whether Himmler and Göring were present at Hitler’s briefing. However, this conviction was not shared by the other conspirators. They were insistent that as a bare minimum Himmler must also perish in any explosion. That this view was not impressed on Stauffenberg before he departed is baffling, but when he arrived Stieff relayed the message to him and, when it was clear that only Hitler would be present, Stieff aborted the operation. Stauffenberg was understandably perplexed and angry, and adding to his indignation was the fact that he knew that troops in and around Berlin had been placed on alert to march into the government quarter and seize key sites once the Valkyrie order was issued.

Showing admirable composure Stauffenberg attended the various briefings but excused himself on two occasions to make calls to his co-conspirators. He pressed them to reconsider their thinking that both Göring and Himmler had to die at the same time and to seize the opportunity, but they were not for turning. Frustrated, he called Mertz von Quirnheim and they decided to act unilaterally, but by this time the briefings had concluded and the chance was gone. The units that had been put on alert were stood down and told it was simply an exercise. However, when Fromm heard about what had happened he reprimanded Olbricht; no such liberties could be taken in the future. Mobilization could now only happen after the attempt on Hitler’s life, which introduced a delay into the plan that would prove critical on 20 July.

When Stauffenberg arrived back in Berlin he held a post-mortem. Mertz von Quirnheim provided a gloomy appraisal of the conspirators in the Bendlerblock, who, he believed, lacked the courage to see the exercise through to its conclusion. Indeed, it seemed that they were greatly relieved to learn that the assassination attempt had been called off. Dispirited, but not deterred, the pair agreed to kill Hitler come what may, and time was now of the essence. On 17 July news reached them that a warrant for the arrest of Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, former Lord Mayor of Leipzig and for so long the leader of the civilian resistance, had been issued. More worryingly, they later learned of the rumours circulating in Berlin that some kind of attack was to be perpetrated at the Wolfsschanze in the near future. Stauffenberg decided he had to strike now, whether Göring and Himmler would be killed at the same time or not. Hitler had to be eliminated and he would be the man to do it. In so doing he was prepared to renounce his oath of allegiance and accept the almost certain charge of treason and the penalty that went with it.

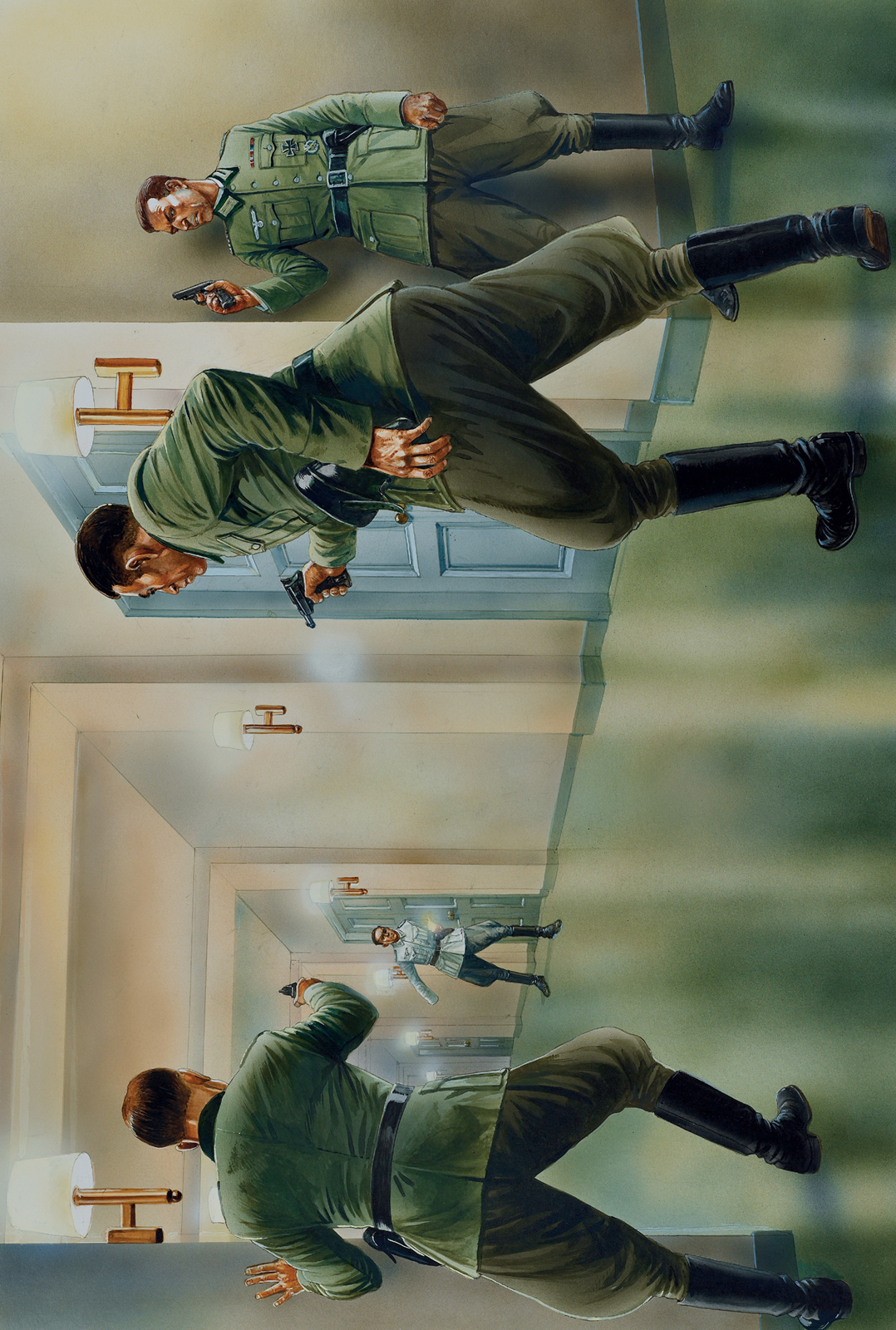

While working as Fromm’s chief of staff, Stauffenberg lived with his family in a house on the Tristranstrasse. Stauffenberg travelled from here to Rangsdorf airport in Berlin, from where he flew to the Wolfsschanze and planted the bomb. (Topfoto)

On 18 July Stauffenberg received orders to head to the Wolfsschanze on the 20th to brief Hitler; he was to provide details of plans for the establishment of two new divisions to defend East Prussia. The day he received his orders coincided with the departure of his wife and family to Lautlingen, south of Stuttgart, for their summer vacation. Stauffenberg asked his wife Nina to delay their departure, but the tickets had been bought and so they duly set off. On 19 July Stauffenberg tried to call his wife but he was unable to get through because of an Allied air raid. The next morning he was due to fly to the Wolfsschanze with the explosives to assassinate Hitler.

On the morning of 20 July Gefreiter (Lance-Corporal) Karl Schweizer drove Stauffenberg to Rangsdorf Airfield to take the regular courier flight to the Wolfsschanze. Haeften, Stauffenberg’s aide-de-camp, met him at the airfield and the two boarded the flight. Schweizer set the briefcase containing the explosives next to Stauffenberg. As they prepared to leave Schweizer was directed to collect Stauffenberg and Haeften from the airfield that afternoon.

The plane landed at Rastenburg shortly after 1000hrs and Stauffenberg was taken to the Wolfsschanze, where he had breakfast with members of the Camp Commandant’s staff, including Hauptmann Heinz Pieper, a staff officer who arranged Stauffenberg’s car, and Rittmeister Leonhard von Möllendorff, a personnel officer. Meanwhile Haeften and Stieff, who had joined Stauffenberg on the flight, headed to Mauerwald with the explosives. After breakfast Stauffenberg had to attend a series of briefings, the last of which was at 1130hrs with Generalfeldmarschall Keitel. Although not invited to this meeting, Haeften returned to the Wolfsschanze and, while discussions continued in Keitel’s office, he loitered in the corridor with the explosives. Unsurprisingly for a man involved in a plot to kill the Führer, he appeared a little agitated and was challenged by one of Keitel’s NCOs, Oberfeldwebel (Sergeant) Werner Vogel, but Haeften was able to convince him nothing was amiss.

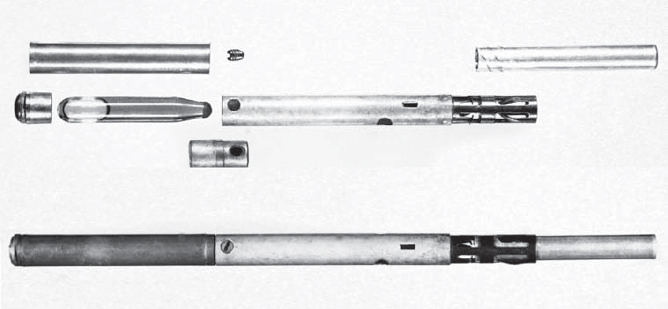

A fuse of the type used by Stauffenberg to detonate the explosives. The complete fuse is shown at the bottom and broken into its component parts above. On the left can be seen the acid in its capsule. When broken the acid would eat through a wire, which would release the spring-loaded firing pin. (NARA)

At much the same time, Heinz Linge, Hitler’s valet, called Keitel’s office to remind him that, because of a visit by Mussolini, the briefing with Hitler had been brought forward by 30 minutes and would now start at 1230hrs. Soon after this message was received, the shuttle railway car from Mauerwald7 was espied and Major Ernst John von Freyend informed Keitel accordingly. Keitel now brought the meeting to a close, so that he would not be late for Hitler. This posed something of a dilemma for Stauffenberg who needed time to prime the explosives. However, this eventuality had already been anticipated and Stauffenberg asked for time to freshen up and change his shirt. This he did with the help of Haeften, and he then prepared the explosives and fuses.

Stauffenberg and Haeften had two blocks of plastic explosive – more than enough for the task. However, the fuse was difficult to set, especially for a man with only one hand, in spite of the fact that the pliers he used had been specially adapted for his use.8

To begin with, the fuse had to be removed from the primer charge. Then the metal casing had to be pinched with pliers to break the glass vial inside, which contained acid that would slowly eat away the wire holding the striker pin. Finally, once this had been done, the safety pin had to be removed and the fuse reinserted in the primer charge.

One pack of explosives had been prepared when they were interrupted by Oberfeldwebel Vogel. Ironically, part of the reason for his interruption was to let them know about a call from General der Nachrichtentruppe (General of Signal Troops) Erich Fellgiebel, a fellow plotter. Vogel remained at the door insisting that Stauffenberg hurry. He received a brusque response, but with no opportunity to prime the second pack of explosives, Stauffenberg dropped the first into his briefcase and composed himself. Haeften concealed the second pack in his briefcase. John von Freyend now called from the entrance for them to hurry up; Keitel and the others were waiting outside and were growing impatient. To help Stauffenberg, John von Freyend offered to carry his briefcase; his offer was firmly but politely declined.

Stauffenberg walked to the briefing with General der Infanterie Walter Buhle, his former commanding officer. When they reached the briefing hut, Stauffenberg passed the briefcase containing the explosives to John von Freyend and asked to be given a place near the Führer, in order to ‘catch everything I need for my briefing afterwards’ (quoted in Hoffmann 1996: 399). Stauffenberg’s hearing had been damaged when he was wounded in North Africa.

When Stauffenberg and the others entered the Lagezimmer (briefing room), Generalleutnant Adolf Heusinger was already providing an outline of the situation on the Eastern Front. Keitel announced Stauffenberg and Hitler shook his hand. John von Freyend now placed the briefcase under the table and Stauffenberg took his place next to Heusinger, who was in turn next to Hitler. Konteradmiral Hans-Erich Voss, representing the Kriegsmarine commander-in-chief, Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz, moved to the other side of the table. The briefing resumed and Hitler leant over the table, magnifying glass in hand. Stauffenberg now surreptitiously moved the briefcase as close to Hitler as possible, but recognized that one of the substantial legs of the table was in the way. To have tried to place it any closer would have aroused suspicion.

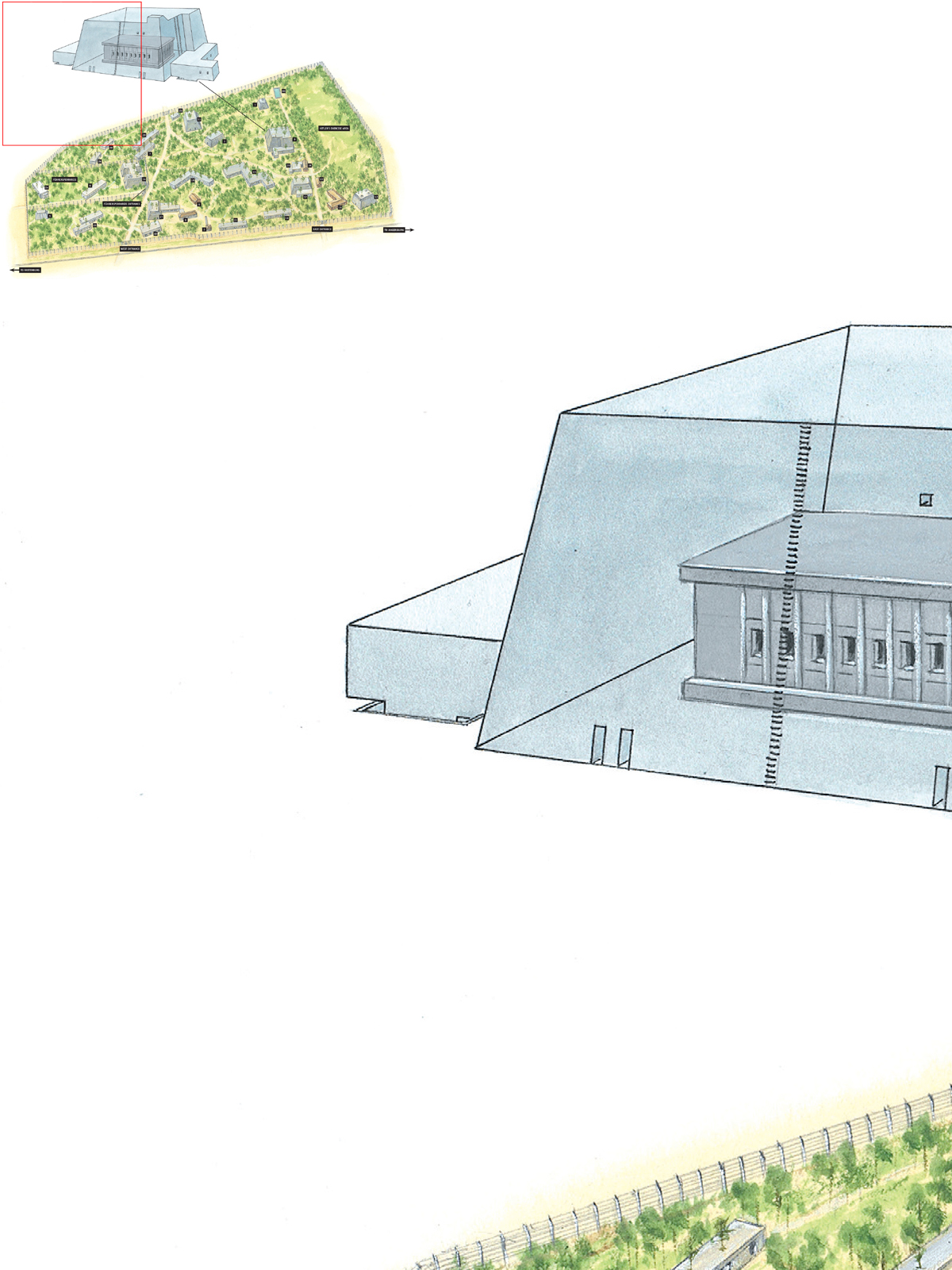

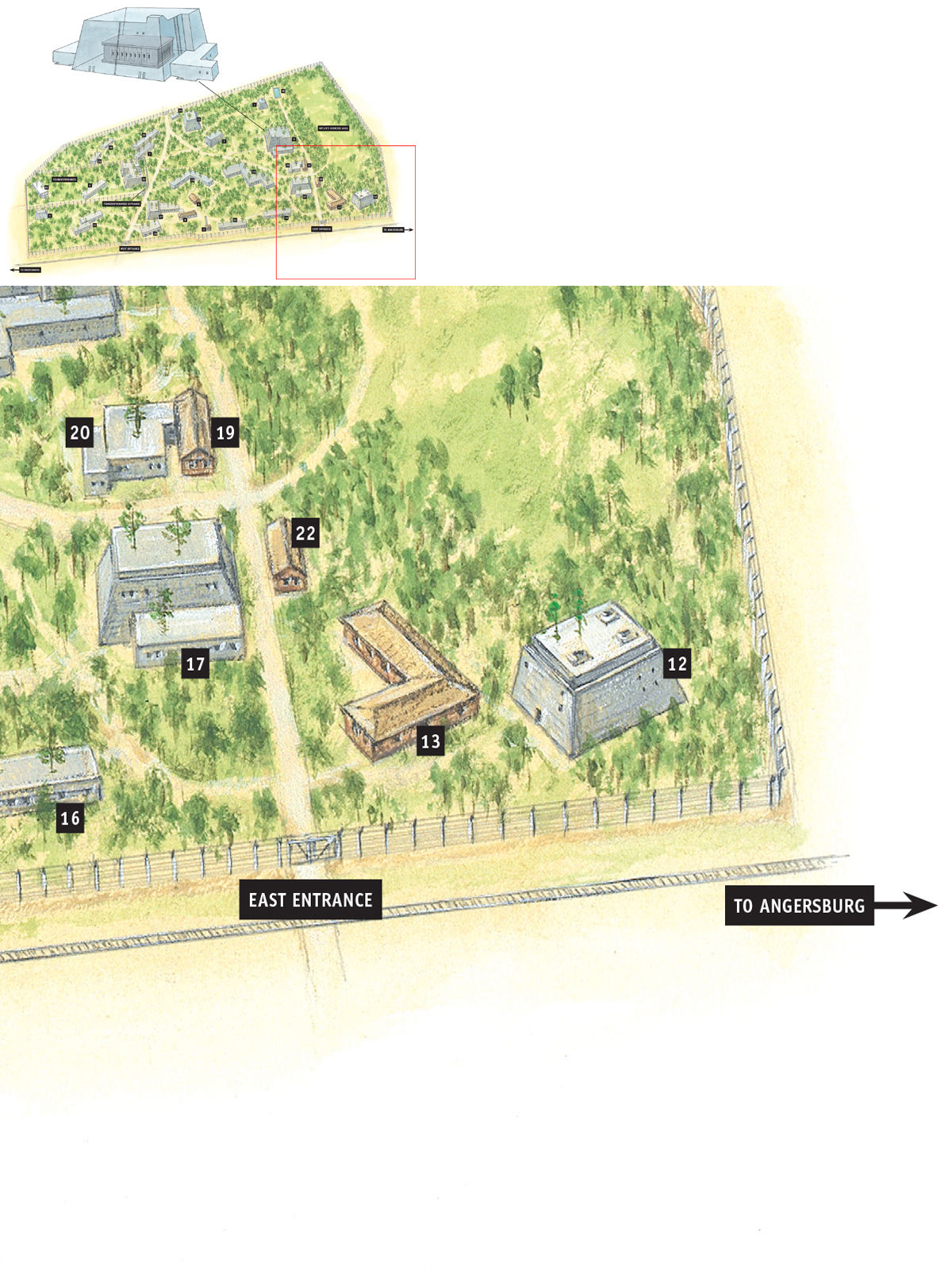

1. Anti-Aircraft Bunker

2. Boiler House

3. Bormann’s Bunker

4. Briefing Hut

5. Bunker

6. Cinema

7. Detective Detail; Post Office

8. Drivers’ Quarters

9. Führerbunker

10. Garages

11. General-Purpose Bunker

12. Göring’s Bunker

13. Göring’s Offices

14. Guest Bunker

15. Hitler’s Personal Adjutants’ Offices; Army Personnel Office

16. Jodl’s Offices

17. Keitel’s Bunker

18. Liaison, Medical and Support Offices

19. New Teahouse

20. Officers’ Mess I

21. Officers’ Mess II

22. Old Teahouse

23. Press Bunker

24. RSD and SS barracks

25. Sauna

26. Security Building

27. Signals Bunker

28. SS-Begleit-Kommando; Servants’ Quarters

29. Stenographers’ Offices

30. Water Reservoir (for fighting fires)

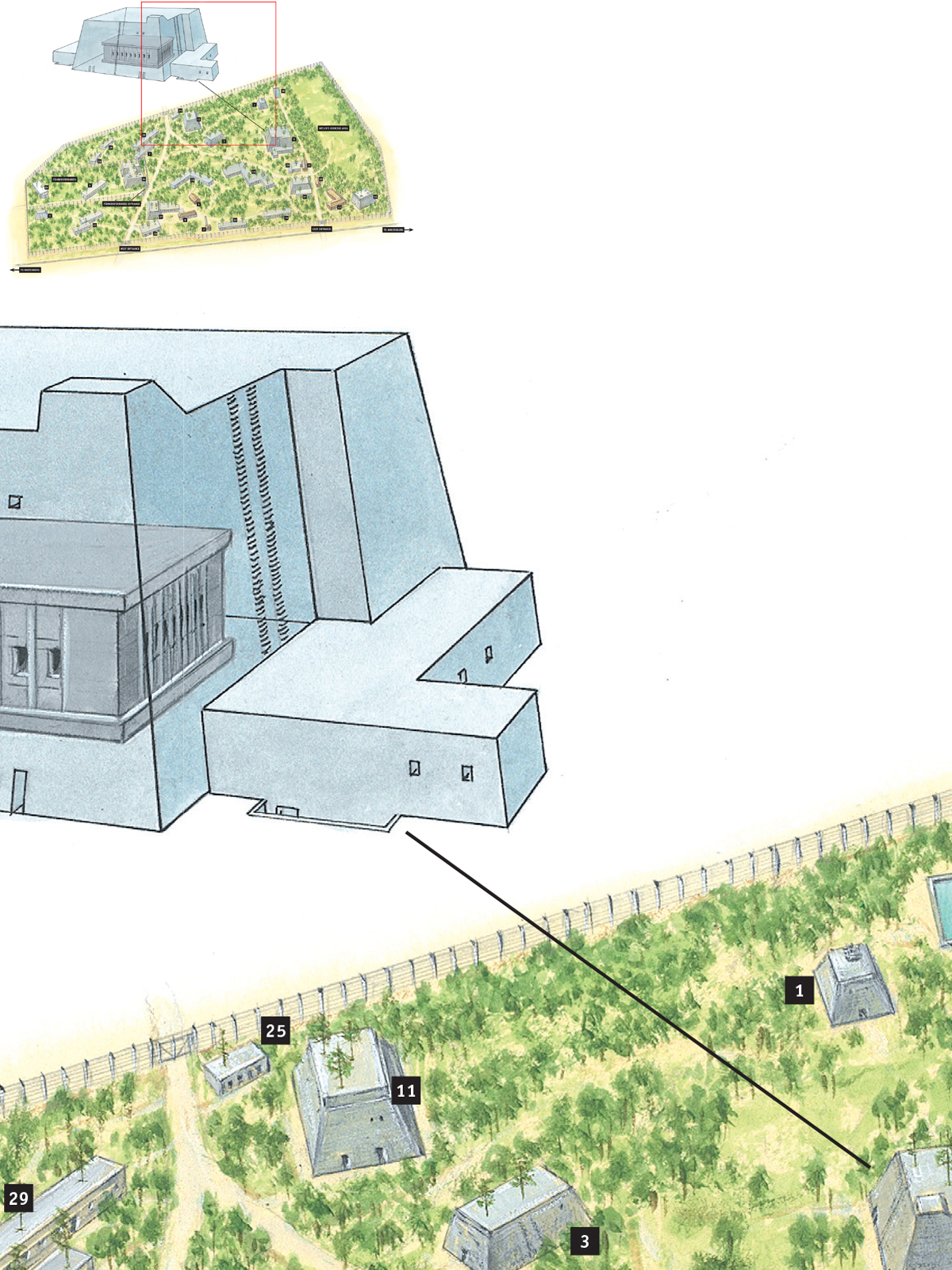

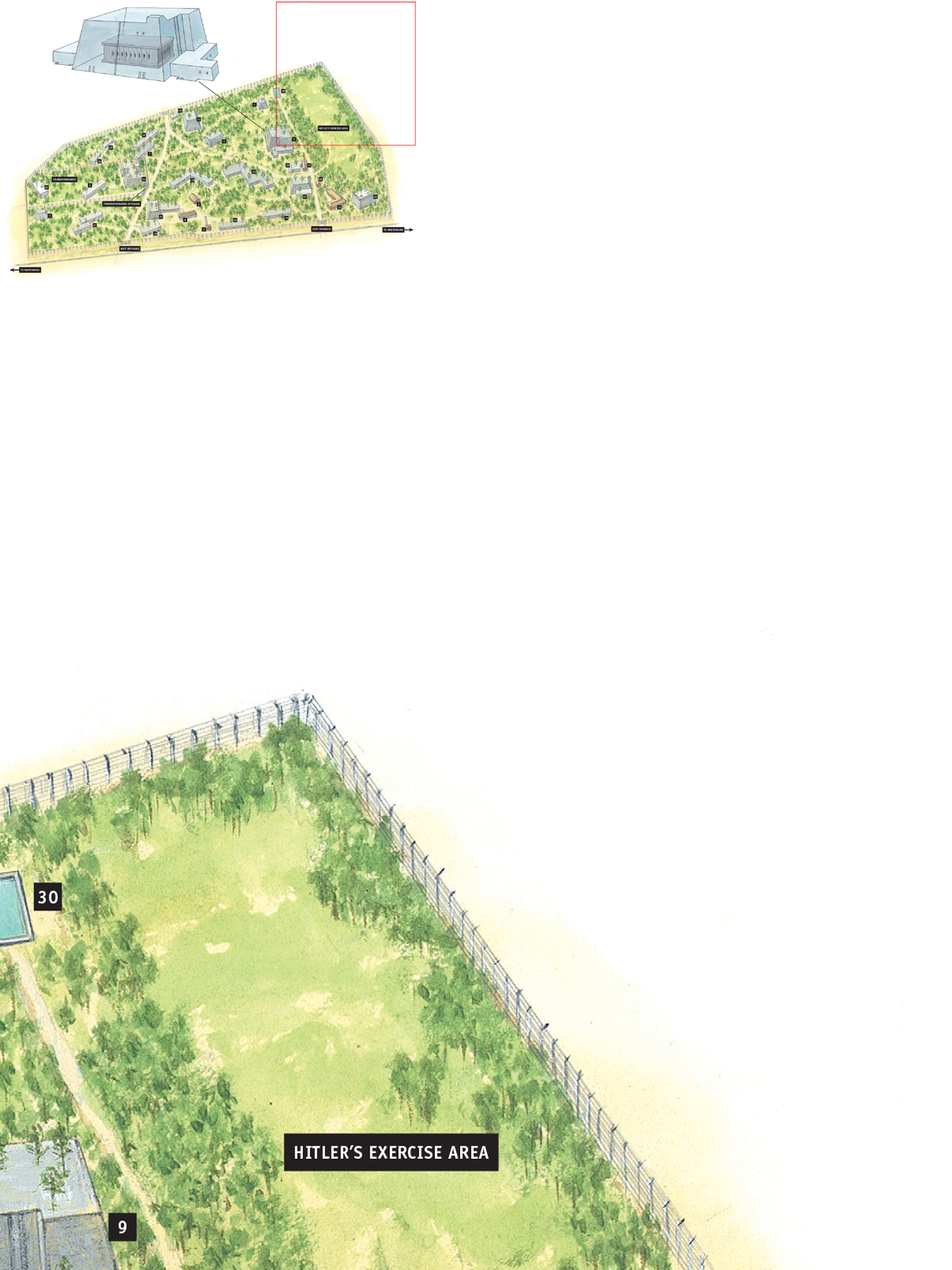

The briefing on 20 July was held in the briefing hut. This was a long, low building with the briefing room at one end. This was reached by means of a long corridor that ran down the centre of the building (shown). The blast was such that the doors along the length of the corridor were damaged. (Topfoto)

View from the entrance to the briefing room towards the windows at the end of the block. It was the height of summer and in the middle of the day so all the windows were open, which helped to dissipate the blast. Even then, the damage was extensive. (NARA)

The first part of the mission complete, Stauffenberg signalled to John von Freyend that he needed to make a call and the two of them exited the room. John von Freyend asked the telephone operator, Wachtmeister (Sergeant-Major) Arthur Adam, to call Fellgiebel and then returned to the briefing. Stauffenberg didn’t wait for the connection, but left the building (leaving his hat and belt) and went off to the Adjutantenhaus (adjutant’s building), which was some 200m from the briefing hut. Here he met Fellgiebel and Haeften, who in the interim had been finalizing arrangements for the car to take them to the airfield. This had been supplied with the intention of taking Stauffenberg for a lunch appointment with Oberstleutnant Gustav Streve, the camp commandant. However, Streve was about to be disappointed; his lunch date had another more pressing engagement in Berlin.

The explosives were left in a briefcase, which was placed on the floor near Hitler. When the explosives were detonated the force of blast moved out from the epicentre, but did little damage to the floor. The carpet was damaged and a small hole blown in the floorboards. (NARA)

As Stauffenberg and Fellgiebel left the office the explosives detonated, startling both of them; Oberstleutnant Sander, the Wehrmacht signals officer, was unsurprised, however, believing it to be one of the mines laid around the perimeter being detonated by an unlucky animal. Stauffenberg, knowing the truth, explained he would not return to the conference but would go straight to lunch. He bade farewell and stepped into his car along with Haeften. The driver, Leutnant Erich Kretz, noticed that Stauffenberg had forgotten his hat and belt, but Stauffenberg insisted he drive on. As they headed off, Stauffenberg and Haeften could see smoke emanating from the briefing hut and figures running to and from the scene. Amid the chaos, they saw someone carried out under Hitler’s cloak. Stauffenberg was sure that this was the Führer. He was mistaken, however; fearing a further explosion, Hitler had been spirited away to his bunker.

Only a few minutes earlier the briefing room had been a picture of calm. After Stauffenberg left the conference, Oberst Heinz Brandt, who was standing next to him, pushed the briefcase a little further under the table so that it was not in his way, but he did not move it to the other side of the leg as is sometimes suggested. Heusinger continued to provide his update on the Eastern Front and, during his presentation, a point was raised that Stauffenberg would have been able to answer, but he was absent. Buhle went looking for him, but could only ascertain from Wachtmeister Adam that Stauffenberg had left the building. Then, just after 1240hrs, the bomb exploded. Warlimont recalled:

In a flash the map room became a scene of stampede and destruction. At one moment was to be seen a set of men and things which together formed a focal point of world events; at the next there was nothing but wounded men groaning, the acrid smell of burning, and charred fragments of maps and papers fluttering in the wind. (Warlimont n.d.: 440)

The explosion had blown a hole in the floor and had wrecked the heavy table. The plasterboard covering the walls and ceiling had been badly damaged and the glass fibre behind was strewn around the room.

Everyone in the room tried to escape the carnage; there was the very real danger that there might have been another bomb or that the roof might collapse. Warlimont scrambled through a window. Once outside he regained his composure and was aware that Oberst Brandt was also trying to escape from the devastated room. However, he had been so badly injured that he was unable to extricate himself and had to be helped to safety by John von Freyend – a feat von Freyend repeated in also rescuing the badly injured Generalleutnant Schmundt. Once outside and away from the danger, John von Freyend proceeded to cut away Schmundt’s boot so that his wounds could be treated. Meanwhile, Warlimont attempted to re-enter the building to collect his papers, but by this time the area had been secured by SS guards and when he did make it into the briefing room he collapsed and had to be evacuated by his personal staff.

View of the briefing room taken from in front of the windows at the far end of the block. The force of the blast was such that it demolished one of the internal stud walls, behind which was the telephone room. The smaller round table in the conference room is just visible on the left. (NARA)

Like Warlimont, Oberst Nicolaus von Below had also made a miraculous escape. At the start of the meeting he was away from the main table, discussing the visit of Mussolini with the other adjutants. However, Heusinger made an interesting point and Below moved to study the map. At that point the bomb exploded and he was momentarily knocked unconscious. When he came round he was greeted by a scene of utter devastation. Recognizing the danger, he exited through a window and made his way to the front entrance, where he witnessed some of the injured being removed from the building. Eleven attendees were hospitalized, the remainder suffering minor injuries including burst eardrums.

Astonishingly, Keitel, who was on Hitler’s left at the briefing, was unhurt and, though shocked, soon regained his senses and immediately called after Hitler. Searching through the dust and smoke he found him and led him out. Aside from his clothing, which had been shredded, he seemed fine. Hitler’s personal aide, SS-Gruppenführer Julius Schaub, and the Führer’s valet, SS-Obersturmführer Heinz Linge, hurried to the scene and helped Hitler back to his bunker for a medical examination. This was initially conducted by Professor von Hasselbach who dressed the Führer’s wounds, but he was later relieved by Doctor Morell, Hitler’s personal physician, and Hasselbach headed for Karlshof hospital near Rastenburg to treat the others wounded in the blast.

While the wounded were being evacuated to hospital, Below made his way to the Nachrichtenbunker (signals bunker), where he explained what had happened to the duty officer, Oberleutnant Hans Hornbogen. He in turn called Oberstleutnant Ludolf Sander, the Wehrmacht signals officer, who immediately returned to the exchange. When he arrived he ordered that no messages were to be sent unless from Hitler, Keitel or Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, OKW Chief of Operations. This was a stroke of luck for Fellgiebel, whose orders from the conspirators in the Bendlerblock were to stop all communication from the Wolfsschanze so that the conspirators could enact Valkyrie. Although Fellgiebel was head of army and Wehrmacht communications, his authority over the latter was limited and it would have been difficult for him, without support at a more junior level, to establish a communications blackout.

Hitler after the assassination attempt, apparently showing no signs of physical injury. Just behind him is Bormann, his private secretary, who was not at the conference. To Hitler’s left is Generaloberst Jodl with his head bandaged, and behind him is Oberst von Below, one of Hitler’s adjutants, who was also slightly injured. (Topfoto)

From the signals bunker, Below, still slightly concussed, walked the short distance to Hitler’s quarters in the guest bunker. Hitler was still in shock, but was sufficiently compos mentis to ask his adjutant how he was and to affirm that they had all been very lucky (at this point he was unaware of the fatalities). At about the same time Hitler received a number of other visitors, including his secretaries, Traudl Junge and Christa Schroeder.

At lunchtime all the secretaries had been in their rooms. The Wolfsschanze was quiet but the peace was broken by an explosion. This was alarming but not unusual, because there was building work going on and weapons were often tested. And, like Oberstleutnant Sander, they were aware that occasionally wild animals would set off one of the land mines protecting the site, so they took little notice and carried on with their duties. However, it soon became clear that something was wrong as Traudl Junge heard calls for a doctor. She left her room and spoke to two orderlies coming from Hitler’s compound, who explained that there had been an explosion.

Junge now ran towards the briefing room and met Jodl, who was covered in blood. Concussed and with burst eardrums, Jodl could not understand Junge, and security staff now ushered onlookers away. Fearing the worst, Junge went back to her room. Minutes later SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Günsche, Hitler’s personal adjutant, passed the secretaries’ quarters. He seemed fine and Junge spoke to him. He confirmed there had been an explosion, and hypothesized that a rogue Organization Todt worker, employed to reinforce the buildings, had planted a bomb. Reassuringly, he confirmed that the Führer was fine and suggested that Junge go to Hitler’s bunker, which she did.

When she arrived, she found the Führer looking a little dishevelled, but alive: ‘His hair … was standing on end so that he looked like a hedgehog. His black trousers were hanging in strips from his belt, almost like a raffia skirt’. His right arm was badly bruised, so he greeted her with his left and explained that this was ‘Yet more proof that Fate has chosen me for my mission …’ (Junge 2004: 130).

Christa Schroeder also visited Hitler that afternoon. He welcomed her with a little difficulty, but aside from that he seemed fine. He explained that ‘The heavy table leg diverted the explosion … I had extraordinary luck! If the explosion had happened in the bunker and not in the wooden hut, nobody would have survived …’ (Schroeder 2009: 122). Hitler then showed his secretary his shredded trousers and asked that they be sent to the Berghof where they should be carefully preserved.

On 20 July 1944 Oberst Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg travelled to the Wolfsschanze ostensibly to brief Hitler on the state of the Replacement Army. However, among his papers Stauffenberg also had explosives and detonators which he was to use to kill Hitler. The plan was simple. At the briefing he would place the bomb, now primed and secreted in his briefcase, next to Hitler before making his excuses to leave. The bomb would explode killing Hitler and his immediate circle of advisors. With the Führer dead the conspirators would introduce martial law, seizing key buildings and arresting those loyal to Hitler. Once power had been wrested from the Nazis a new government would be introduced which would seek to end the war. The bomb exploded as planned, but unbeknown to Stauffenberg, who had left the room and was now heading to Berlin, Hitler survived with only minor injuries. As the dust settled, it soon became clear what had happened and with communication links still open Hitler was able to confirm that he was safe and well and his supporters quickly rounded up the conspirators, who were tried and executed.

Hitler’s injured right arm was in fact a bruised elbow; he had also suffered minor burns to his legs and his left hand had abrasions. Both of his eardrums had burst and, although his ears were bloody, his hearing did not appear to be affected. Patched up, Hitler retired to his room and changed, ready to greet the Duce who was due in an hour. Soon afterwards, Fellgiebel saw Hitler walking inside his compound. Shocked, he called Generalleutnant Fritz Thiele, his chief of staff at OKW in Berlin, with his news. Thiele now spoke to Olbricht, who in turn contacted General der Artillerie Eduard Wagner, Deputy Chief of the Army General Staff at Zossen (the site of the OKH headquarters, located 30km south of Berlin). They agreed that they would do nothing until they had definitive news either way concerning Hitler’s fate.

An orderly holds the trousers that Hitler was wearing at the briefing on 20 July. The devastating power of the blast is clear from the way the trousers have been shredded. Surprisingly, Hitler received relatively few injuries. (Topfoto)

While this was going on, Stauffenberg and Haeften made their way to the airfield, convinced that their mission had been a success. They negotiated the first checkpoint relatively easily; the guards had lowered the barrier on hearing the explosion, but with no reason to stop anyone they allowed Stauffenberg to pass. The two conspirators and their driver now made their way to the outer perimeter and the final checkpoint before the airfield. This proved more problematic. By the time they reached this gate the alarm had been sounded and the headquarters was in lockdown. Nothing was allowed in or out. Stauffenberg’s powers of persuasion did not sway the guards. A call was made to Rittmeister von Möllendorff, who had had breakfast with Stauffenberg that morning. Assuming that his dining companion had urgent business in Berlin, he ordered that he be allowed to pass, although he did not have authority to do this. The barrier was raised and the driver accelerated away. They now made haste to Rastenburg Airfield and on the way took the opportunity to dispose of the unused explosives. The driver saw a package being thrown into the undergrowth, but thought little of it at the time and dropped his passengers safely at their destination. Wagner’s He 111 was waiting for them, fuelled and ready to go, and at 1315hrs they took off.

With the situation in the signals bunker secure, Oberstleutnant Sander made his way to the briefing hut to check on the equipment there. Wachtmeister Adam was still at his post, although clearly there was nothing to do as far as his communications role was concerned. He asked permission to speak to Sander and explained that Stauffenberg had left the conference immediately before the explosion, implying that the officer was in some way involved. Sander was outraged and explained he wanted to hear nothing more of the tale, and that if he was convinced of his facts he should speak to security. Adam did better than that: he spoke to Martin Bormann, Hitler’s private secretary, who ushered him in to speak to Hitler. Adam’s story proved to be correct and he was handsomely rewarded with a promotion, money and a house.

The briefing hut was a simple prefabricated structure. The walls were made from wooden slats with plasterboard on the inside. Between the two was a layer of fibreglass for insulation, remnants of which can just be seen. A bullet-proof coating was added to the outside. (NARA)

A search for Stauffenberg was ordered. However, it soon became clear that he had boarded a plane at Rastenburg and had left the headquarters. The driver who had taken Stauffenberg to the airfield was now questioned. He confirmed that Stauffenberg had flown out and that something had been thrown from the car on the journey. Troops were immediately ordered to check the roadside, where they found the discarded explosives. Stauffenberg was clearly implicated in the plot and Himmler was now made responsible for bringing him, and any other conspirators, to justice. Himmler had been ordered to the Führer’s presence, along with Göring, immediately after the explosion, but they were not told what had happened. Once briefed, Himmler and SS-Obergruppenführer Dr Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (RSHA – Reich Central Security Office), set off for Berlin, flown by SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Doldi, one of SS-Brigadeführer Hans Baur’s pilots (Baur was chief pilot to Hitler), who had come straight from the dentist.

Mussolini was due for a meeting with Hitler on 20 July. Following the bomb blast Hitler invited the Duce to inspect the damage with him. The two leaders are standing at the end of the corridor leading to the briefing room. On the right is the chief interpreter at the Foreign Office, Dr Paul Otto Schmidt. (Topfoto)

Patched up and changed, Hitler prepared to greet Mussolini. The two met at Görlitz station at 1430hrs. Hitler greeted his visitor, exclaiming, ‘Duce! I have just had the most enormous stroke of good fortune’ (quoted in Irving 2002: 703). He explained what had happened and took Mussolini to the scene of his miraculous escape, before returning to business, briefing the Duce about the war effort, including the new V-2 rockets that would soon enter service. At 1700hrs Hitler sat down for tea with Mussolini.

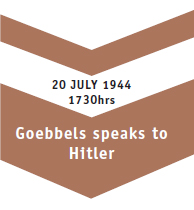

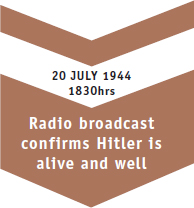

Soon after, a call came through from Goebbels in Berlin. It was clear that moves were afoot to unseat Hitler and he asked the propaganda minister to broadcast a message confirming he was alive. The conversation at the tea party resumed and was dominated by the attempt on Hitler’s life. The exchanges became increasingly heated as Grossadmiral Dönitz and Joachim von Ribbentrop, the foreign minister, criticized the generals for their betrayal. Hitler sat quietly for the most part, but at one point mention was made of the Röhm plot of 30 June 1934. At this, Hitler sprang to life and threatened vengeance on the traitors. His diatribe lasted a full 30 minutes, before he settled back in his seat. The silence was filled by his cohorts, who pledged allegiance to Hitler in increasingly overblown terms that culminated in a fierce argument between Göring and Ribbentrop. At 1900hrs the tea party concluded and Mussolini left – the two leaders would never meet again.

Back in Berlin, the plotters awaited word from the Wolfsschanze, but when it came it was ambiguous. Fellgiebel reported that ‘Something terrible has happened, the Führer is alive’ (quoted in Hoffmann 2008: 268). To Thiele and Olbricht this could mean one of two things. It could be that the bomb had not been detonated (as had been the case before), or that Stauffenberg had been discovered. If the latter was true then it was likely that Stauffenberg had either been killed by Hitler’s bodyguards, or he had done the honourable thing and committed suicide to protect his co-conspirators. What they do not appear to have considered is the possibility that the bomb had detonated, but that Hitler had survived.

Having dismissed this alternative, or never considered it feasible in the first instance, they believed that the best course of action was inactivity. After the events of 15 July, they certainly could not order an alert. Fromm had been furious the last time and certainly would not endorse an order to mobilize when the message from the Wolfsschanze was equivocal. Neither could Olbricht and Thiele act independently; the Führer was, after all, seemingly alive and as such there were no special circumstances that might incline those asked to act to actually do so. No, they would carry on as normal, and so they went to lunch. Once definitive news had been received, then they would act – not beforehand. Not until 1500hrs did they return to the office. In stark contrast, Oberst Mertz von Quirnheim, who had heard the news of Hitler’s survival at the same time, was far more proactive and pressed ahead with the first part of Valkyrie. At about 1400hrs he sent out the orders to place units on alert.

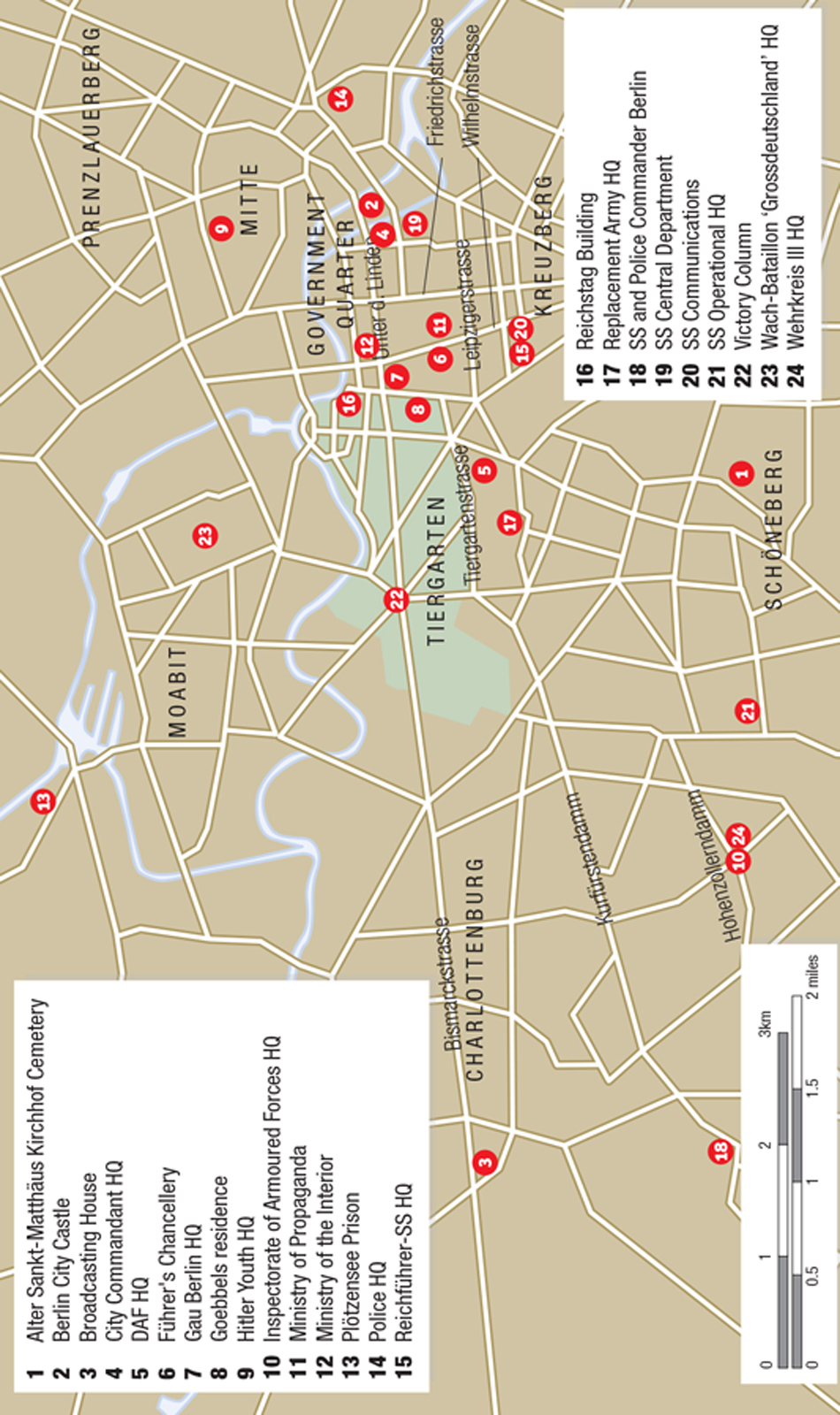

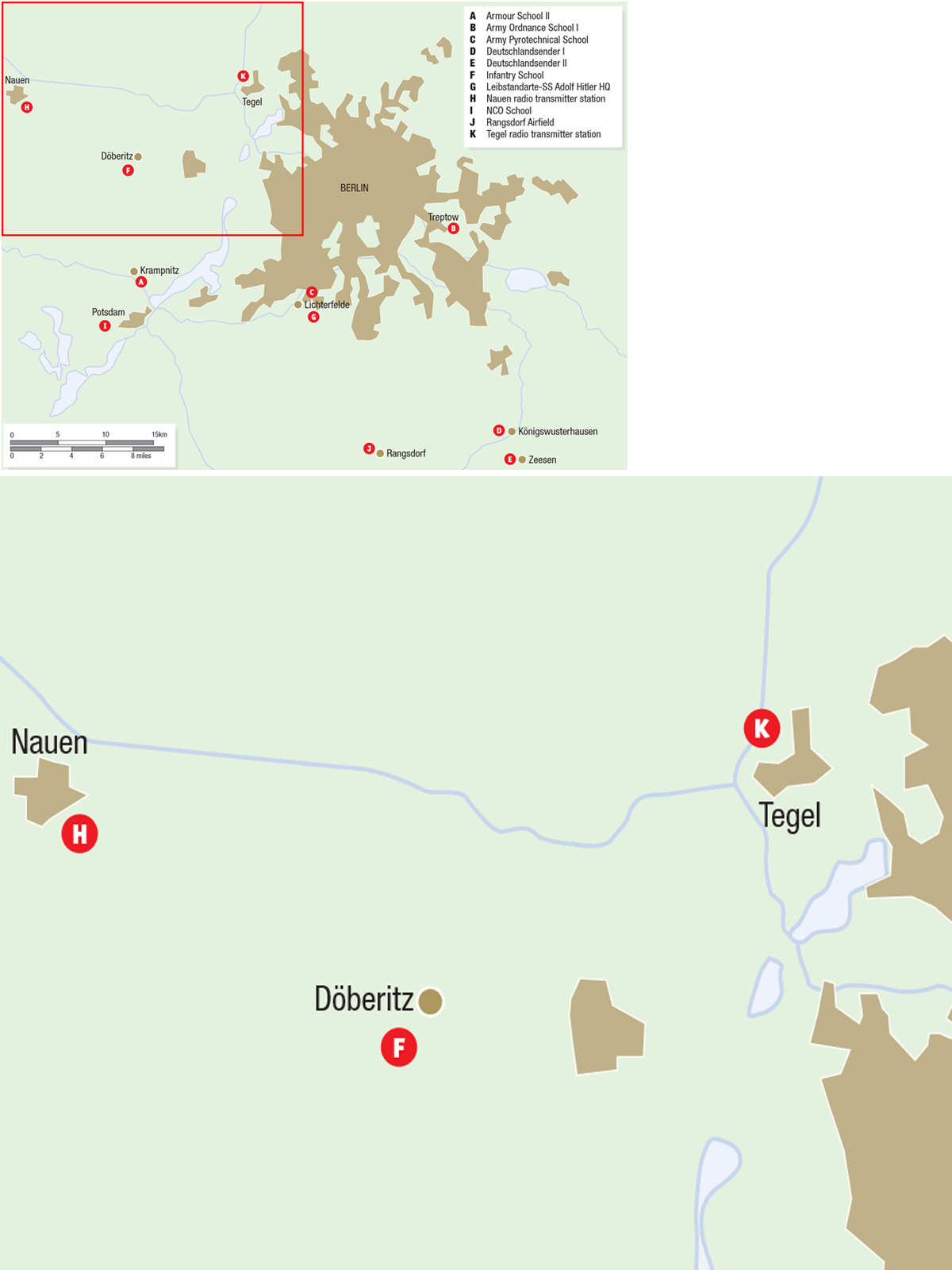

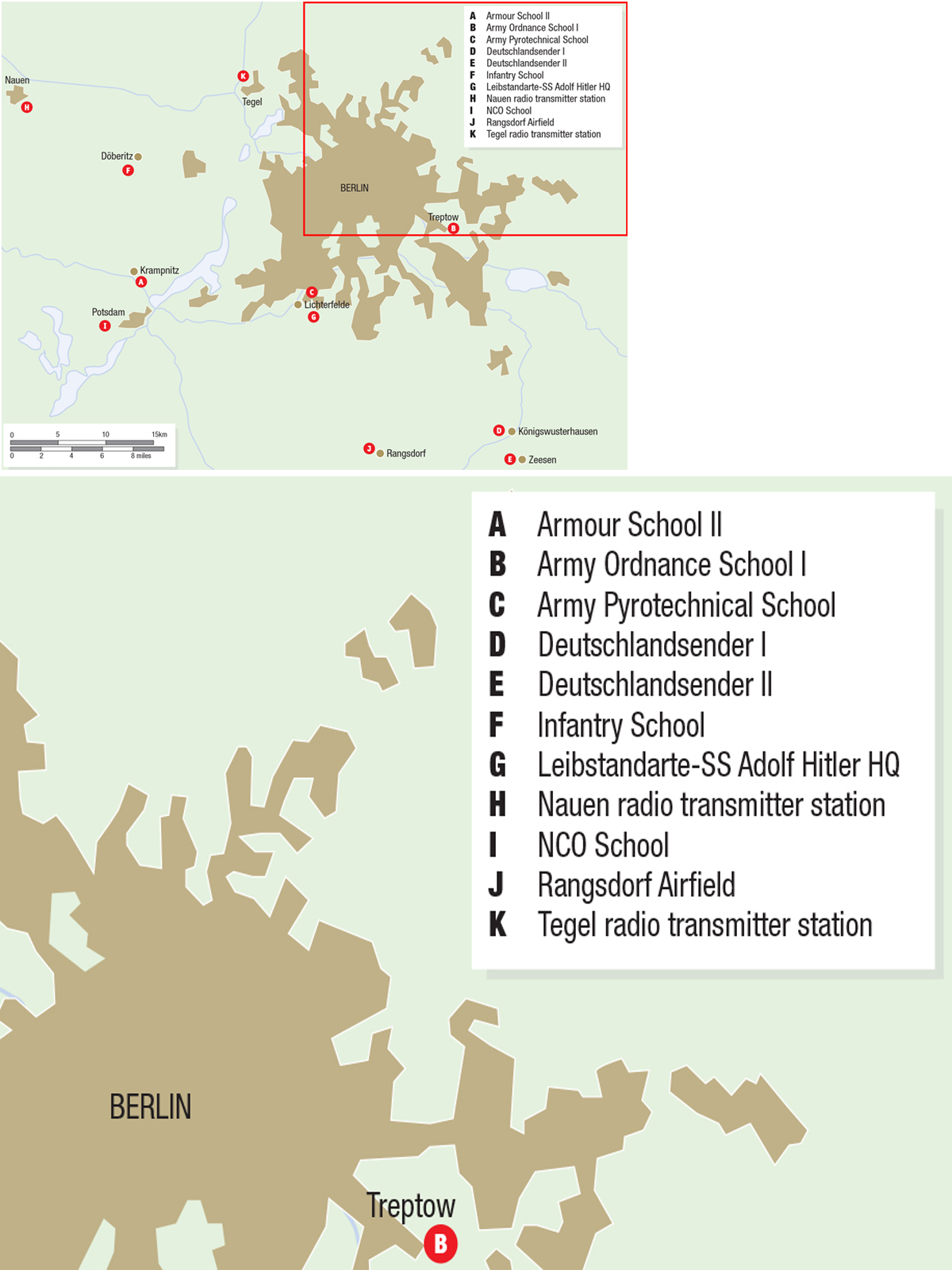

Berlin and its environs, 20 July 1944. Deutschlandersender III at Herzberg lies to the south – see the map on page 47.

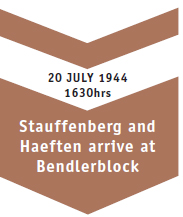

At about 1545hrs, Stauffenberg and Haeften arrived at Berlin’s Rangsdorf Airfield, but when they alighted they found their transport was not there. Schweizer had gone to the airport, but for reasons that are unclear he missed his passengers. Stauffenberg spoke to the officer in charge at the airfield (having done a trial run, he knew him) and managed to get a car. During the delay, Haeften called ahead to the Bendlerblock to confirm Hitler’s death. With no sense that a different version of events had percolated through from the Wolfsschanze, they now set off to drive the 30km to the Bendlerblock, arriving at 1630hrs.

Once Mertz von Quirnheim was aware of Stauffenberg’s arrival in Berlin, he pressed Olbricht to set in motion the second stage of Valkyrie. Olbricht still prevaricated, but eventually decided to accept that the Führer had been killed. Mertz von Quirnheim now briefed the staff in the Bendlerblock that Hitler was dead, that Beck was Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State) and that Generalfeldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben was now Wehrmacht Commander-in-Chief. At just before 1600hrs the codeword ‘Valkyrie Stage 2’ was issued to all Wehrkreise (military districts) and, importantly, to the various units in Berlin. At the same time the orders were removed from the safe for Fromm to sign, and both Mertz von Quirnheim and Olbricht went to see the commander of the Replacement Army.

The two officers explained the situation to Fromm, but understandably after the debacle only five days before he was reluctant to sign. Anticipating this, and now convinced that Stauffenberg’s view of events was correct, Olbricht organized an urgent call to Keitel. Fromm spoke to Keitel, explaining that rumours were circulating in Berlin concerning the Führer’s wellbeing. Keitel confirmed that there had been an explosion, but that Hitler was fine. Keitel now turned from the quizzed to the quizzer, asking after Stauffenberg’s whereabouts. Fromm replied that he had not yet returned to Berlin.

During the attempted coup on 20 July, Goebbels was in Berlin where he was instrumental in crushing the uprising. However, once the danger had passed, he visited Hitler at the Wolfsschanze. Göring and Goebbels are shown the damage by Hitler. SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, who was at the conference, is in the foreground. (Topfoto)

Unperturbed, Olbricht and Mertz von Quirnheim left Fromm and, at 1630hrs, they issued a general order to all Wehrkreise. It was from Witzleben and stated:

The Führer Adolf Hitler is dead … In order to maintain law and order in this situation of acute danger the Reich Government has declared a state of martial law and has transferred the executive power to me together with the supreme command of the Wehrmacht … Any resistance against the military authorities is to be ruthlessly suppressed. (Quoted in Noakes 2010: 621)

The length of the message (the passage above is abridged), the number of addressees and the fact that the text had to be entered into the Enigma encoding machines meant it took an incredible amount of time and effort to send. Consequently, it didn’t arrive in some military districts until much later in the day, when some key officers had gone home. They had to be contacted and then make their way to their respective headquarters, adding further to the delay in implementing the order. Witzleben’s order was followed by a further message calling on units to secure key buildings (radio stations, telephone exchanges, etc.) and for the arrest of party officials (at Gauleiter,9 minister and governor levels) and senior Gestapo and SS officers.

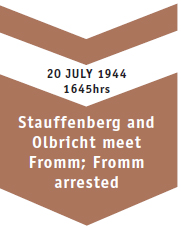

When Stauffenberg arrived at the Bendlerblock he reiterated that Hitler was dead and at the same time was brought up to speed on developments in Berlin, not least Fromm’s intransigence. Stauffenberg and Olbricht went to see Fromm and once again Stauffenberg confirmed what he had seen and stated categorically that Hitler was dead. Fromm challenged his version of events based on his discussion with Keitel, to which Stauffenberg countered that Keitel was one of Hitler’s lackeys and was always lying. Olbricht now confirmed that the Valkyrie order had been issued. Fromm was outraged; he slammed the desk and in no uncertain terms made it clear that what they were doing amounted to treason, the penalty for which was death.

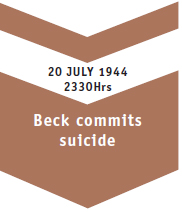

Fromm now demanded to know who had issued the Valkyrie order. Olbricht explained it was Mertz von Quirnheim, and he was now summoned to Fromm’s presence where he confirmed that he had indeed issued the order. Understanding the full implications of what had happened, Fromm sought to save himself and ordered the plotters be placed under arrest. Stauffenberg, the picture of calm, ignored this idle threat and reiterated that the Führer was dead. Fromm vigorously disagreed and suggested the honourable thing for Stauffenberg to do was shoot himself; Stauffenberg declined. A scuffle ensued, and Fromm, having been given one last chance to join the coup, was relieved of his duties and was placed under house arrest.

The Wehrkreise: Events on 20 July 1944

I (Königsberg): Units engaged in anti-partisan duties so few troops available and as such could not carry out orders even if they wanted to. Commander, General der Artillerie Albert Wodrig, spoke to neighbouring Wehrkreise, who were doing nothing. Spoke to Keitel who insisted that the only orders to be followed were from the Wolfsschanze. Stauffenberg’s call not taken.

II (Stettin): Commander, General der Infanterie Werner Kienitz, sympathetic to coup. Received teleprint and called neighbouring Wehrkreise. Situation unclear so waited. Received call from Keitel explaining what had happened. Later called by Hoepner and Olbricht and told to follow Valkyrie orders. Keitel outranked them so this direction was ignored.

III (Berlin): See main narrative.

IV (Dresden): Received teleprint orders. Headquarters secured and troops put on alert. At same time received a call from Keitel who explained all messages from Berlin were to be ignored. Phoned neighbouring Wehrkreise, who had adopted a ‘wait and see’ approach. Then heard radio message about coup and Hitler’s survival – nothing more done.

V (Stuttgart): Teleprints arrived late, decoding took time and the revolt had already collapsed before decisions could be taken. No units alerted.

VI (Münster): First teleprint order arrived. Before second message the operations officer, Oberst Kuhn, spoke to Stauffenberg, who explained formal orders would follow and should be adhered to. Keitel called and explained Hitler was well and orders from Berlin were to be ignored. No units mobilized.

VII (Munich): No orders received from Berlin before coup had effectively ended due to the heavy Allied bombing. When Keitel called in the evening he was told all was quiet.

VIII (Breslau): Units occupied with anti-partisan duties so few available for Valkyrie. When Stauffenberg called, chief of staff, Generalmajor Ludwig Freiherr Rüdt von Collenberg, had not seen the orders. Stauffenberg did not elaborate. Generalleutnant Wilhelm Burgdorf, deputy head of the Heerespersonalamt (Army Personnel Office), called and told Collenberg to ignore orders from Berlin. Called other Wehrkreise. The message was the same; Hitler was alive, do nothing.

IX (Kassel): Plans in this Wehrkreis were more advanced because a number of the officers in charge were part of the conspiracy. When the order came, the commander, General der Infanterie Otto Schellert, was away and did not return until late. Briefed by his chief of staff, Oberst Claus-Henning von Plate, and, in spite of the contradictory messages received, Schellert did issue the Valkyrie order and some buildings were secured. However, after a call from Keitel and having spoken to other Wehrkreise, it became clear to Schellert that the coup had failed and the orders were cancelled.

X (Hamburg): Both the commander, General der Infanterie Wilhelm Wetzel, and chief of staff, Generalmajor Friedrich-Wilhelm Prüter, were absent when the teleprint arrived ordering the commencement of Valkyrie. When Prüter returned to the headquarters he put units on alert. Later he rang other neighbouring Wehrkreise and found they had not acted. The few orders that had been issued were later cancelled as it became clear that Hitler was alive and the coup had failed.

XI (Hanover): Teleprints arrived late, decoding took time and the revolt had already collapsed before decisions could be taken. The commander, General der Infanterie Benno Bieler, called Stauffenberg but did not get a satisfactory answer to all his questions. Later Keitel called Bieler to explain Hitler was alive and that the coup was being crushed. He decided not to act.

XII (Wiesbaden): Teleprints arrived late, decoding took time and the revolt had already collapsed before decisions could be taken.

XIII (Nuremberg):Teleprints arrived late. Commander, General der Infanterie Mauritz von Wiktorin, spoke to Berlin and the Wolfsschanze and received contradictory orders, so adopted a ‘wait and see’ approach.

XVII (Vienna): See main narrative.

XVIII (Salzburg): Teleprints arrived late. Oberst Glasl, chief of staff, heard from the Wolfsschanze that Hitler was alive before hearing that Hitler had been assassinated. No action was taken.

XX (Danzig): Commander was Keitel’s brother, General der Infanterie Bodewin Keitel. Wehrkreis close to front and Keitel on inspection when orders arrived. Later checked with sibling and situation explained. Did nothing to enact orders from Berlin.

XXI (Posen): Wehrkreis close to combat zone and no reserve units to speak of. Most senior officers on tours of inspection, so teleprints not seen till late. Clear that no action being taken in other Wehrkreise and Burgdorf called to confirm Hitler was alive. No action taken.

Böhmen und Mähren (Prague): See main narrative.

General Government (Krakow): Orders were received by Generalmajor Max Bork, the chief of staff, but by the time they arrived he had already heard the radio messages of the Führer’s survival. At 2200hrs Stieff called to say orders from Berlin were to be ignored. When Burgdorf called, Bork explained that orders had been received but had not been actioned, thanks to Stieff.

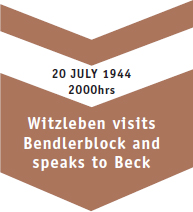

After this explosive episode, the situation in the Bendlerblock settled down. The orders had been issued and the plotters now had to wait for the troops to mobilize. Following Fromm’s arrest, another message was sent detailing the appointment of Hoepner as commander of the Replacement Army; later still, advice was issued insisting that the radio broadcasts talking of Hitler’s survival were wrong and that the Valkyrie orders should be carried out with the utmost speed. Meanwhile, Beck and Hoepner had now appeared at the Bendlerblock. Both arrived in civilian clothes, Beck to avoid suspicion of a coup and Hoepner because in December 1941 Hitler had denied him the privilege of wearing uniform. Both now took up their respective positions in the new regime: Beck as Head of State and Hoepner as commander of the Replacement Army. Hoepner made his way to Fromm’s office and spoke to the man he had replaced. Fromm’s view had not changed. Hitler was still alive, he insisted, and it was a mistake to continue with the Putsch (coup d’état). It was too late, however – the orders had been issued.

Meanwhile, Beck spoke to General der Artillerie Wagner at Zossen, explaining the situation and stating that Witzleben would soon be with him to take over as commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht. The Bendlerblock was the headquarters for the Replacement Army, where most of the plotters worked, but Zossen, the OKH headquarters, was much better equipped for the commander-in-chief to direct operations. After this call Wagner received a call from Stieff at the Wolfsschanze. Stieff understood that the Valkyrie orders had been issued, but he was also aware that Hitler had survived and insisted that to continue was madness. Wagner now asked Stieff to tell Keitel what was happening and of the calls Wagner had received from the Bendlerblock. Later, Wagner stated that he had never supported the coup, but this attempt to cover his trail – he had lent Stauffenberg his aircraft after all – did not save him. He committed suicide on 23 July.

While this was going on, Stauffenberg focussed his energies on maintaining the momentum in the coup. He called the various military districts and reiterated that Hitler was dead and what the orders were. However, the reaction to the Valkyrie orders was patchy (see previous pages).

The first teleprint from Berlin arrived in Vienna at about 1800hrs, when most of the senior officers had left. On reading the message Oberst Heinrich Kodré, chief of staff, contacted the acting commander, General der Panzertruppe (General of Armoured Troops) Hans-Karl Freiherr von Esebeck, and requested he return to Wehrkreis XVII headquarters, which he did. At the same time a platoon of Wach-Bataillon Wien (Vienna Guard Battalion) was ordered to deploy around the headquarters. This was followed by the receipt of the second teleprint from Berlin ordering the arrest of Nazi officials, SS and SD personnel. As a first step Kodré ordered all senior officers in Wehrkreis XVII to report to the Old War Ministry (the Kriegministerium, located in Vienna’s Stubenring) for a conference at 1900hrs.

When Esebeck arrived, he read the messages and agreed with Kodré that they should be followed, but just to double-check Kodré rang Stauffenberg, his counterpart in Berlin, who confirmed that the orders were correct and urged him to enact them with the utmost speed. By now the senior officers (or their deputies) had begun to arrive at the Old War Ministry. At 1920hrs the conference began. Those present were briefed on developments and were directed to enact the Valkyrie order in their respective areas. Generalleutnant Adolf Sinzinger, City Commandant of Vienna, was tasked with arresting party dignitaries and senior SS officers. However, rather than frogmarch the accused to Wehrkreis XVII headquarters, they were to be invited and then detained; force was only to be used as a last resort.

As part of the investigation into the bomb plot, evidence was gathered to establish how the attack was carried out and by whom. These are the pliers that were used by Stauffenberg to break the glass vial that would detonate the explosives. They were left in the briefcase and damaged in the blast. (NARA)

Understandably, some of the individuals invited to the Old War Ministry were suspicious about the request, especially at this late hour. Most did turn up, though some had to be cajoled into entering the building and others came armed. When they were all assembled they were briefed on the orders received and specifically the order to arrest them. They accepted that Esebeck was only doing his duty and submitted to incarceration, the inconvenience being eased by the provision of brandy and cigars.

A teleprint was now received in Wehrkreis XVII headquarters detailing the appointment of political representatives to take up key roles in the city. These individuals were known to be unsympathetic to the regime, which raised doubts in Esebeck’s mind about what was going on. These concerns were heightened with the receipt of a further message stating that the radio message talking of Hitler’s survival was untrue. If any doubt remained, it was swept away by a telephone call from Keitel, who impressed on Kodré and Esebeck in no uncertain terms that Hitler was alive and that the orders from Berlin were not to be followed. In a later call, Stauffenberg tried to convince Kodré of the need to keep his nerve, but the call was cut off. Kodré and Esebeck tried to call Witzleben, but without success; later they spoke to Burgdorf, who confirmed that a Putsch had been attempted but it had been unsuccessful and power still rested with Hitler. The Valkyrie orders were now cancelled and all the prisoners were released. The following day Esebeck, Sinzinger and Kodré explained themselves to Baldur von Schirach, the Gauleiter, but without success and they were imprisoned until the end of the war.

Oddly, the adherence to the Valkyrie order was much more successful outside Germany and Austria. This was surprising because the German units in Czechoslovakia and France were in ‘occupied’ countries and were therefore surrounded by a population that was hostile to German forces of whatever hue. There was consequently a very real danger that any Putsch could lead to internal unrest.

In Prague, General der Panzertruppe Ferdinand Schaal, the commander of Wehrkreis Böhmen und Mähren (Bohemia and Moravia), heard of the assassination attempt while at a reception. The message had come from a radio broadcast that suggested Hitler had survived the attempt. Schaal returned to his headquarters where he received the Valkyrie order. Confused, he tried to speak to Fromm but was put through to Stauffenberg, who confirmed that Hitler was dead and told him to implement the emergency powers immediately. Schaal mobilized his troops and secured strategic locations, but, before he took further steps to arrest senior Nazis, SD and SS figures, he tried to call Karl Hermann Frank, the German Minister of State for Bohemia and Moravia. Schaal’s logic was simple: the SS was stronger than the army in Prague and any arrests would undermine security in the city.

By the time the two men eventually spoke, Frank had received word from the Wolfsschanze that he was only to act on orders from the Führer. Schaal and Frank agreed to meet at a neutral location to discuss the matter, but before Schaal left he, too, received a call from the Wolfsschanze informing him of the coup and that only orders from Keitel and Himmler, the new head of the Replacement Army, were to be obeyed. With this new information he met with Frank and it was agreed that no further action would be taken. When Schaal visited Frank the next day he was also arrested and detained until the end of the war.

In Paris the orders were successfully implemented, due in no small part to the fact that a number of senior officers were actively involved in, or at least aware of, the plot.

On the afternoon of 20 July General der Infanterie Günther Blumentritt, chief of staff to Commander-in-Chief West, was informed that Hitler was dead and that a new interim government had been formed. Blumentritt tried to contact Generalfeldmarschall Kluge, who had been appointed commander-in-chief west on 2 July 1944, at La Roche-Guyon. However, Kluge was at the front and the call was taken by Generalleutnant Dr Hans Speidel, Army Group B’s chief of staff. However, because Blumentritt was not aware of the plot, he did not explain to Speidel what the call concerned and instead drove to La Roche-Guyon to await the return of Kluge.

Meanwhile in Paris, Oberstleutnant Cäsar von Hofacker, who was one of the conspirators, received news from Stauffenberg that the coup was under way; Hofacker immediately briefed his commander, General der Infanterie Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, commander-in-chief France. Stülpnagel acted directly, calling in his senior officers, including Generalleutnant Hans Freiherr von Boineburg-Lengsfeld, the City Commandant of Paris, who was ordered to arrest all SS personnel. This he did, but to ensure these troops would be in their barracks – and to avoid the local populace witnessing an unseemly struggle between Germans – he ordered that it take place after dark. When Kluge returned to his headquarters he spoke to Beck, who briefed him about the events of the day and stressed the importance of Kluge’s involvement. In response Kluge asked for time to think and after the call he asked Stülpnagel to come to La Roche-Guyon for a conference.

While Kluge pondered his next move, reports arrived of a radio broadcast stating that Hitler was alive. Kluge now called Generalmajor Stieff, an old colleague, at Mauerwald, and asked him what he knew. Stieff confirmed that Hitler was alive. Still not convinced, Kluge called Fromm in Berlin, but was passed to Generaloberst Hoepner, who maintained the radio reports were wrong and that Hitler was dead. Kluge was understandably confused; he now received orders from Berlin calling on the army to take control and arrest SS units and, importantly, stating that the radio messages reporting that Hitler was alive were untrue.

By this time Blumentritt had arrived and, buoyed by the news, Kluge discussed with him plans for agreeing a ceasefire in the west. It was now 2000hrs and events took another turn. Kluge received a message from Keitel stating that Hitler was alive and he changed his mind again. With Hitler alive the coup could not succeed, Kluge argued, and he wanted nothing more to do with it. When Stülpnagel and Hofacker arrived he reiterated his stance, which put Stülpnagel in a difficult position because he was well aware of the actions he had set in motion in Paris. Stülpnagel’s only hope was that the success of his plan might change Kluge’s mind. It did not. When he heard about events in Paris Kluge was furious. He relieved Stülpnagel of his command and ordered Blumentritt to cancel the order, but it was too late.

GENERALFELDMARSCHALL ERWIN ROMMEL

Rommel, commander-in-chief of Army Group B, was aware of plans to overthrow Hitler, but believed the timing of any coup was critical and that it should not be conducted before the Allied invasion. His logic was sound. In the spring of 1944 German troops in the west were convinced they could repel an Allied landing. If the Western Allies were defeated, Churchill and Roosevelt might have foregone their insistence upon an unconditional German surrender. To kill Hitler at such a time might have precipitated civil war, allowing the Soviets to capture most, if not all, of continental Europe.

Once the invasion had taken place and the Allies had secured a foothold, Rommel’s thinking changed. It was clear they would soon break out of the bridgehead and that there was little or nothing to stop them reaching Germany. This being the case, he was happy to support an attempt on Hitler’s life. He was set on this course when, on 17 July 1944, he was seriously injured in an air attack and was hospitalized.

When Rommel recovered he learned of the failed plot and the fallout. He was critical of Stauffenberg, arguing that ‘… he had bungled it … a front line soldier would have finished Hitler off’ (quoted in Liddell Hart 1953: 486). This was a harsh appraisal and born out of the cruel treatment meted out to the conspirators by Hitler’s henchmen. Rommel himself was not to escape.

After Rommel had been injured, Hitler wrote to him: ‘Accept, Herr Field Marshal, my best wishes for your continued speedy recovery. Yours Adolf Hitler’ (quoted in Liddell Hart 1953: 493). But his view of Rommel changed. In the purge that followed the 20 July Plot, Rommel was implicated. Hitler could not risk putting him in front of the People’s Court, however, because the appearance of such a well-known and highly respected military leader might give succour to others who had reservations about the regime. Rommel would be offered a choice: suicide, followed by a full state funeral and the assurance that his name and his family would be protected; or, alternatively, he would be tried by the People’s Court, which would result in his death, disgrace and penury for his family. He chose the former and on 14 October 1944 he committed suicide near his home in Ulm.

Boineburg-Lengsfeld had issued the order and, unlike in Berlin, it had been quickly and efficiently carried out. The barracks of the SS were surrounded and the occupants arrested and marched off to the Wehrmacht prison. Details of the night’s events were secretly passed to SS-Oberführer Kurt Meyer, commander of 12. SS-Panzer-Division ‘Hitlerjugend’ and to SS-Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich, commander of I. SS-Panzerkorps, but they were too entangled in engagements with the Western Allies to help and could only pass on the information.

While the SS in Normandy was impotent. However, Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe units in Paris were not, and when they heard of the coup attempt, their commanders threatened to liberate the SS men. This proved unnecessary though, as it was now clear the coup had failed and, in the early hours of 21 July, the order was given to release the prisoners. Some of the men who had been incarcerated thought their release was a trick and refused to leave, but it was genuine and, in an attempt to present a unified front, the army and the SS commanders agreed a set of words to explain the night’s events. Kluge congratulated Hitler, and the army and SS men celebrated.

Although support in the wider Reich was important, the key to the coup leaders’ success lay in controlling the capital, Berlin. The conspirators needed to seize key points in the city and this was to be done by mobilizing units controlled by Generalleutnant Paul von Hase, the Berlin City Commandant, and those of Wehrkreis III, which covered Berlin and its environs. This would be difficult because, in order to reduce the chances of compromising the operation, the details of the coup were not known by all those involved; instead, it was believed that officers would follow orders. To complicate things further still, those units stationed in and around Berlin were often transferred to the front at very short notice, as were the officers in charge, so it was unclear from one month to the next what troops would be available and who would be in command.10

Wehrkreis III was commanded by General der Infanterie Joachim von Kortzfleisch, a Hitler loyalist and therefore unlikely to be supportive of the Putsch. Kortzfleisch was therefore in a pivotal position, and so the conspirators agreed that to leave him in post on the day of the coup was too much of a risk; it was decided that once Hitler had been assassinated Kortzfleisch would be invited to the Bendlerblock, arrested and replaced by an officer sympathetic to the coup.

On 20 July Kortzfleisch was sent for and arrived some time after 1700hrs. He expected to meet Fromm, but of course this was impossible and instead he was met by Beck, Hoepner and Olbricht. They explained what had happened but, as suspected, this staunch Nazi was not persuaded by the arguments presented by these luminaries. He refused to believe that Hitler was dead and indeed thought that this might be a coup. Unsurprisingly, he refused to follow the Valkyrie orders and deploy his troops. He made to leave but realized this was impossible and so ran for the exit. After a chase, he was captured and incarcerated and was replaced by Generalleutnant Karl Freiherr von Thüngen.

The initial plan was to use two packs of explosives. However, Stauffenberg did not have time to prime both packs. As the plotters exited the Wolfsschanze, the spare explosive was discarded. It was later discovered by investigators. (NARA)

Back in Wehrkreis III headquarters on the Hohenzollerndamm, it fell to Generalmajor Otto Herfurth, the chief of staff, to action the Valkyrie orders delivered by Major Hans Ulrich von Oertzen. Herfurth was relatively new in post and was not aware of the plan, unlike his predecessor Generalmajor Hans-Günther von Rost, who had been posted in March 1944, and who was part of the conspiracy. The responsibility for carrying out the orders, even with the help of Oertzen, did not sit easily with Herfurth and he called a council of war with his junior officers. Eventually Herfurth conceded that the orders were genuine and mobilized his units, comforted by the fact that it would take some time for them to reach their destination, by which stage things might be clearer. Some time after 1900hrs Thüngen arrived to take command, but as might be expected of someone who was previously the Inspekteur des Wehresatzwesens (Inspector of Recruiting) in Berlin, he was not proactive and did little to expedite the mobilization of the troops under his command.

The units of Wehrkreis III were to seize a number of key buildings in the capital, including party offices, ministries (notably Propaganda and Interior), Gau Berlin headquarters and those of the Hitler-Jugend (Hitler Youth) and the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF – German Labour Front). Importantly, they were also to secure the offices of the SS. However, as Herfurth had noted, it would take time for these units to reach the centre of Berlin; as if to highlight this fact, SS-Oberführer Humbert Achamer-Pifrader arrived at the Bendlerblock from Gestapo headquarters to arrest Stauffenberg and take him to see SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo, but Achamer-Pifrader was himself arrested by men loyal to Stauffenberg.

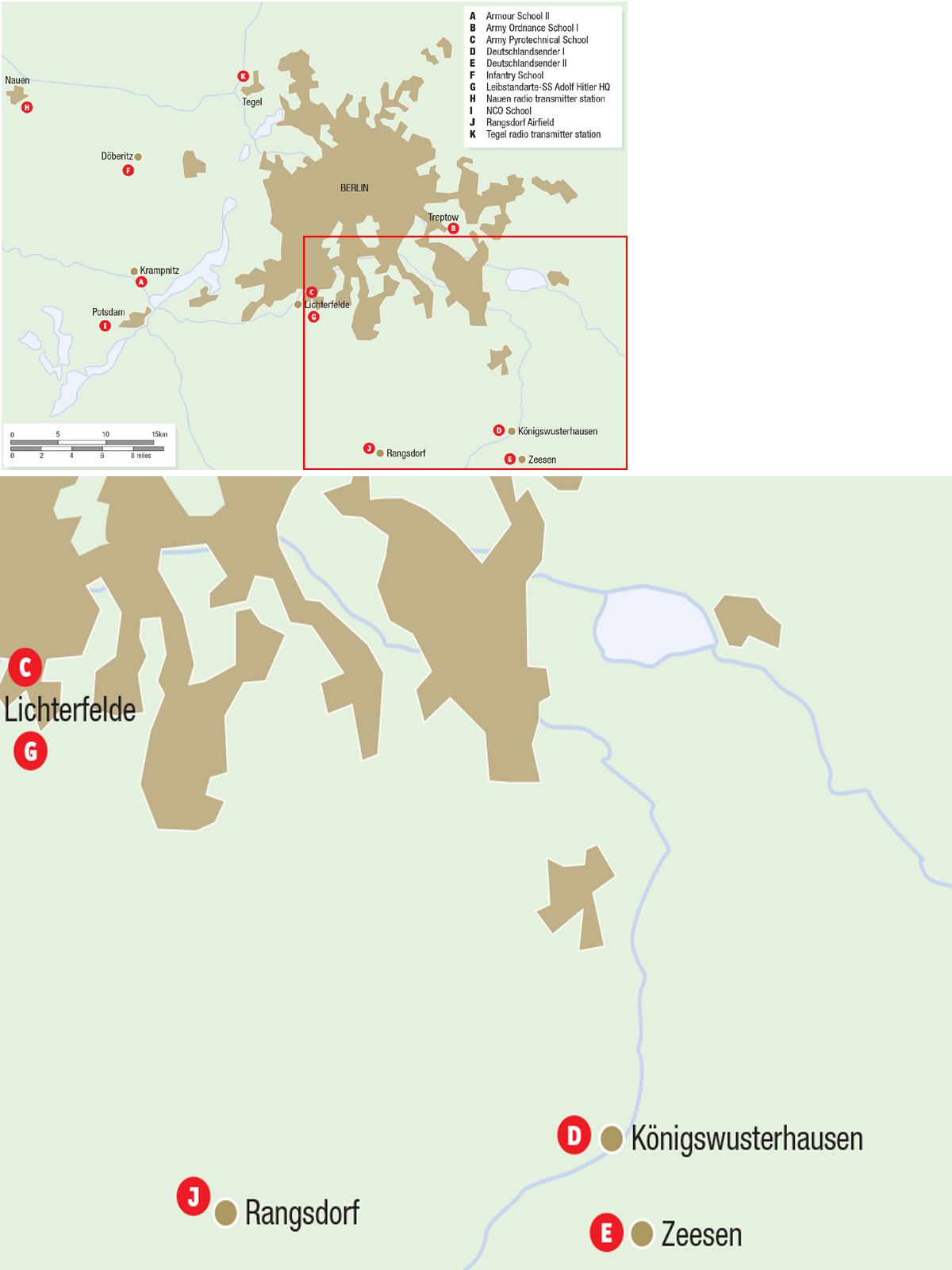

The two principal units of Wehrkreis III were Ersatz-Brigade ‘Grossdeutschland’ at Cottbus, some 80km south-east of Berlin, and the Infanterieschule (infantry school) at Döberitz, some 25km west of the city. Ersatz-Brigade ‘Grossdeutschland’ received news that the Valkyrie order had been enacted at about 1600hrs. Written confirmation arrived soon thereafter and Oberstleutnant Hans-Werner Stirius, in temporary command because Oberst Hermann Schulte-Heuthaus was on exercise, ordered that his men move to the prearranged forming-up point just south of Berlin. When they arrived, one company was ordered to secure the Herzberg radio station (Deutschlandsender III), which it did by 1815hrs; another group was to seize the radio stations at Königswusterhausen (Deutschlandsender I) and Zeesen (Deutschlandsender II), which it did by 2000hrs, relieving troops from Panzertruppenschule II (Armour School II).

Demolished concrete uprights from the main entrance to Gestapo headquarters, which were left after the clearing of the site (1957–63) still with remnants of the metal fittings. All the prisoners sent to the Gestapo headquarters passed through this gate. The remains now form part of the Topography of Terror Museum on Wilhelmstrasse. (Author)

Generalleutnant Otto Hitzfeld, the commander of the infantry school, was also absent (on compassionate grounds) and the Valkyrie order was received by Oberst Albert Ringler. By 1800hrs advance reconnaissance parties were ready to move and Major Jakob, an infantry tactics officer, was ordered to occupy the Haus des Rundfunks (broadcasting house) in the Masurenallee. On arrival he deployed his troops to protect the facility and ordered that all broadcasts be stopped. He was assured that everything had been turned off, but not being an expert and having no signal officers to support him he could not confirm that this was the case. In fact, the studios and switch room had been moved to a bunker nearby and remained on air throughout.

Unaware of this, Jakob attempted to contact the Bendlerblock as ordered, to confirm that he had secured the broadcasting house, but the number he rang was not answered and therefore the plotters were never aware that he had been successful. Of more immediate concern for Major Jakob, however, was a unit of SS soldiers that had arrived on the scene. At first he attempted to place them under his command but they refused to comply and since the SS troops had also been deployed to guard the building, Jakob compromised and both units protected it, as this did not undermine his order. This uneasy alliance remained in place until late on 20 July, when Jakob was informed of what had happened; the following day he withdrew his troops.

Troops from the infantry school were also dispatched to the radio transmitter at Tegel and the overseas transmitter at Nauen. Both stations had been secured by 2100hrs, but again, with no signal experts to support the battle group, the officers in charge were never sure that transmissions had been stopped. Nor had word of their success filtered back to Döberitz. Oberst Müller of the OKH, who was based at the infantry school, attempted to energize the officers there; as far as he was aware the transmitters had not been secured and nothing had been done to seize the Oranienburg concentration camp as ordered. It had ben targeted by the plotters because it was an SS facility close to Berlin, and as such would have been a potential focal point for resistance to the coup.

The officers at the school had received conflicting messages concerning the day’s events and the current situation, and were inclined not to execute the outstanding orders until they had written confirmation. Ringler eventually managed to contact Hitzfeld, who confirmed that the orders were legitimate, and at 2100hrs the troops moved out. At the same time Müller went to the Bendlerblock to seek permission from Olbricht to take command of the unit. He also asked that the troops allotted to secure the concentration camp be redirected to the Bendlerblock. Mertz von Quirnheim drafted the order and it was signed by Olbricht. He now made haste back to the infantry school, arriving at 2300hrs. However, when he arrived the junior officers at the school refused to act; they were now aware of the coup and that forces loyal to Hitler had regained the upper hand. At midnight the troops of the infantry school were ordered back to their barracks.

It is worth pausing at this point to discuss the importance of the signals officers. A key part of the plan was the seizure of the broadcasting house and the various radio transmitters dotted around the capital. All of them were captured, although the plotters at the Bendlerblock were not aware of the fact. More significantly, experts were needed to ensure that these facilities were disabled. Initially it was planned that OKH would provide ten signals officers and OKW ten more. These were to be sent to the City Commandant’s office where they would be directed to specific locations. However, Generalleutnant Thiele from OKW was aware that Hitler was alive and therefore would not supply the ten men he had promised. To make up the shortfall, Oberst Hassel (OKH) agreed to provide 20 signals officers. The signals officers were assembled but never ordered to any of the transmitters, radio stations or the broadcasting house, because they were not aware that these facilities had been captured. If they had been able to shut them down, the broadcasts detailing Hitler’s survival might have been stopped, although there is no guarantee that this would have meant success for the coup.

Hitler at the bedside of Kapitän zur See Heinz Assmann, who was injured in the blast of 20 July. In the next bed is Konteradmiral Karl-Jesko von Puttkamer, who was Hitler’s naval liaison officer. He made a full recovery, and at the end of the war was sent to the Berghof to destroy Hitler’s papers. (Topfoto)

Another important force at the disposal of the conspirators was the Berlin Police Force. Early on 20 July, Major Egbert Hayessen of the General Army Office spoke to the Berlin Police President, Wolf Heinrich Graf von Helldorf. Hayessen was to act as liaison officer between the conspirators and the police to ensure they were ready to act when a state of emergency was declared. The police were intended to play a critical role in Valkyrie. They were to cooperate with the army and establish a series of raiding parties that would be led by police officers. These would each be allocated a Reich ministry with explicit direction to arrest ministers and other key figures. The police were also to support the army in closing roads and diverting traffic in the government quarter, and to set up roadblocks on the Berlin circular autobahn.

At about 1700hrs Helldorf arrived at the Bendlerblock and was briefed by Olbricht, who explained that the Wehrmacht had assumed power following the attempted assassination of the Führer. Before Helldorf left, Beck stressed that he might hear contradictory views from Nazis loyal to the old regime, which he was told to ignore. Helldorf returned to his headquarters on Alexanderstrasse and alerted the Security Police, but, as agreed with Olbricht, did not immediately mobilize his force. By 1900hrs Helldorf had still not received orders to move; he sent an aide to enquire what was happening, but by this time it was too late to do anything. A significant opportunity had been missed.

Within Berlin itself the mobilization was more successful, not least because many of the officers involved were aware of the plans and their troops had less distance to travel. Hase, the City Commandant of Berlin, was briefed by Major Egbert Hayessen on the morning of 20 July. It had originally been planned to brief him at least 24 hours ahead of the assassination attempt but this had not been possible because of the failed attempt on 15 July. In spite of the early notice, it was not until 1600hrs that Hase was telephoned with the second order detailing a state of emergency. Wach-Bataillon ‘Grossdeutschland’ was mobilized and ordered to move to Hase’s headquarters on the Unter den Linden. The battalion’s commanding officer, Major Otto Remer, and those of the other units under his command were also ordered to Hase’s headquarters, where they would be given further orders. The first and most important briefing was to Remer, who was instructed, with his men, to secure the government quarter and arrest Goebbels. Wach-Bataillon ‘Grossdeutschland’ would later be reinforced by units from Armour School II and from other units in the Berlin garrison.

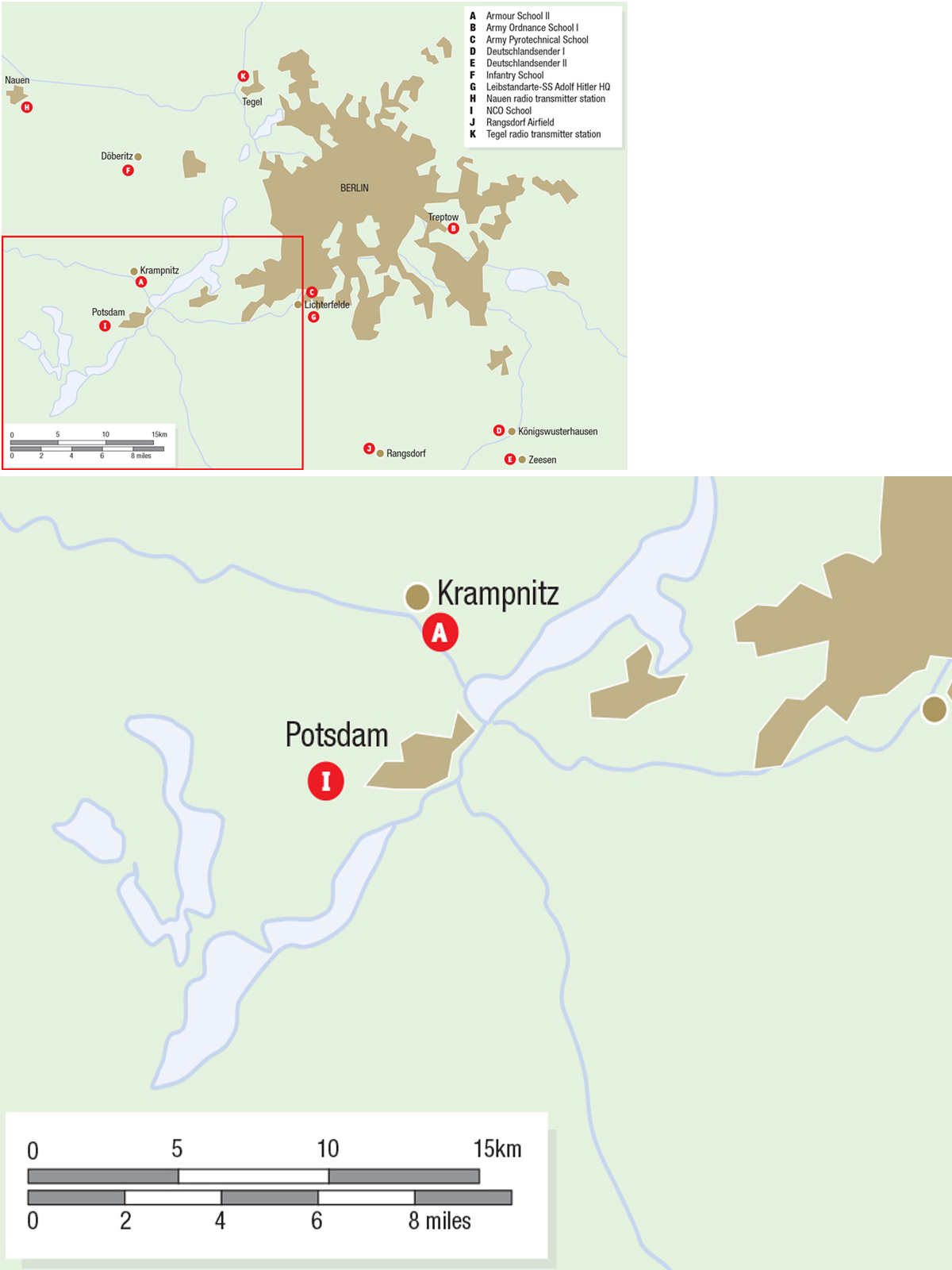

The conspirators recognized early on that armour would be critical to the success of the coup. Armour School II at Krampnitz possessed the most powerful and most mobile units; these were on a high alert to move, which meant that they were ideal for Valkyrie. However, the fact that they could be deployed at short notice also meant that it was impossible for the conspirators to plan with any certainty, because they could never be certain how many tanks and troops would be in Berlin when the blow was struck.

In spite of this uncertainty, Armour School II was given a key role in the coup, but for it to be decisive the tanks needed to roll as soon as news of Hitler’s death reached Berlin. Yet it was not until 1600hrs that Oertzen contacted Oberst Wolfgang Gläsemer, Armour School II’s commanding officer, informing him that a state of emergency existed and the army had taken control. Gläsemer was to direct the units under his command (including a battalion from the infantry cadets’ training course and a battalion from the Unteroffiziersschule [NCO School] at Potsdam) to seize the radio transmitters at Königswusterhausen and Zeesen. They were also to reconnoitre the SS-Leibstandarte ‘Adolf Hitler’ barracks at Lichterfelde and deal with any resistance, but this proved unnecessary as the area was quiet. The rest of Gläsemer’s units were to be concentrated at the Siegessäule (Victory Column) in the centre of Berlin. From here two battalions of troops were ordered to help secure the government quarter, while others protected the Bendlerblock. The rest of the units were to be held as a mobile reserve to deal with any other trouble, principally from the SS garrison commander’s headquarters in Berlin. Once this was done, Gläsemer was ordered to report to the Bendlerblock, where he would receive further orders.

Martin Bormann, Hitler’s personal secretary, and Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, discuss the damage to the conference room in the immediate aftermath of the explosion. They are accompanied by General der Flieger Bruno Loerzer of the Luftwaffe. To the right is the heavy map table that absorbed much of the blast. (Topfoto)

Although Gläsemer had enacted the first phase of the Valkyrie order, he was not comfortable with what was happening. The orders had been received by telephone and not in writing. Later John von Freyend, Keitel’s aide, telephoned Gläsemer and stressed that orders from the Bendlerblock were not to be followed. This added to the sense of unease at Krampnitz and confirmation was sought from Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, Inspector General of Armoured Forces. However, he was unavailable and instead the call was taken by Oberst Ernst Bolbrinker. He in turn spoke to Olbricht, who confirmed the orders were correct, and this message was passed back to Gläsemer. Still not reassured, Gläsemer set off for the Bendlerblock; en route he was given news that an attempt had been made on Hitler’s life, but he had survived and was well.

On arrival at the Bendlerblock, Gläsemer spoke to Olbricht in order to understand exactly what was going on. Olbricht confirmed that Hitler was dead and that Gläsemer was to follow the orders that Mertz von Quirnheim would issue to him. Gläsemer was not persuaded and refused to cooperate any further, stating that this was another stab in the back similar to that of 1918. He was immediately placed under house arrest.

The units from Armour School II, now leaderless, pressed on towards their objectives and assembled at the Victory Column in the Tiergarten. However, by 2130hrs Guderian was aware of what was happening and Bolbrinker ordered the troops to move to the Fehrbelliner Platz, where he was based at the Inspectorate HQ, and not to follow any further orders from the Bendlerblock. By this time Wach-Bataillon ‘Grossdeutschland’ was similarly no longer following orders from the Bendlerblock, and Leutnant Hans Hagen, the unit National Sozialistischer Führungs Offizier (NSFO – National Socialist Leadership Officer), tried to bring the Armour School II units under his control, but he was told that they were only accepting orders from Guderian. Hagen reported this to Major Remer. Still unclear as to which side Guderian was on, Remer called Ersatz-Brigade ‘Grossdeutschland’ at Cottbus and asked for tanks and heavy weapons to be made available should they be needed to counter Guderian’s force. This proved unnecessary; one of Remer’s staff made contact with officers of Armour School II at the Fehrbelliner Platz, who confirmed Guderian’s loyalty to the Führer.

Entrance to the Propaganda Ministry on Mauerstrasse. This looks much as it did in July 1944. The front facade on Wilhelmstrasse was lost during redevelopment after the war. The building is now home to the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. (Author)

Some time after 1600hrs Oberst Helmuth Schwierz, the commander of the Heeresfeuerwerkerschule (army pyrotechnical school), was informed that the Valkyrie order had been issued and that he was required to report to Hase’s office. He was briefed on events and returned to Lichterfelde, where ten squads of 30 men had been readied for deployment. The rest of the school’s complement was ordered to remain at the Lichterfelde barracks under Schwierz’s command to protect it against possible attack from the nearby SS garrison. The 300 troops who had been readied for action were placed under the command of Major Martin Korff and Hauptmann Alexander Maitre, and were ordered to move to the City Commandant’s headquarters. There the two officers in charge received their orders. They were to secure the Propaganda Ministry and arrest Goebbels.11 On arrival at the ministry, Maitre found it was already surrounded by troops of Remer’s Wach-Bataillon ‘Grossdeutschland’. Maitre made his way through the cordon and was informed that there had been an attempted coup and that Remer, under direct orders from the Führer, was in charge of the defence of Berlin. Maitre immediately placed his troops under Remer’s command. When Korff was briefed on events he, too, supported a relieved Remer.

The mobilization of Heereswaffenmeisterschule I (Army Ordnance School I) was almost comical. Its commander, Generalmajor Walter Bruns, a supporter of the coup, received the Valkyrie order like the other commanders just after 1600hrs. His troops were readied to deploy into the city from Treptow, but the transport did not arrive and so they were obliged to move by foot or public tram. This they did, with Nr. 2 and Nr. 3 Kompanien occupying the Berliner Stadtschloss (Berlin City Castle). However, when they eventually arrived at about midnight, they encountered elements of Remer’s battalion, which was no longer following the Valkyrie order. There was a slight contretemps, but unaware of developments the troops of army ordnance school I occupied the castle as ordered. Nr. 1 Kompanie, which had set off earlier than the other companies, had been redirected to the Bendlerblock and arrived there at 2145hrs. At about the same time, troops of Remer’s battalion arrived. Both units had their orders, which were diametrically opposed, and a potentially explosive situation was only diffused when Nr. 1 Kompanie was persuaded to return to barracks.

Wach-Bataillon ‘Grossdeutschland’ was commanded by Major Otto Remer, a former Hitler Youth leader and a Knight’s Cross recipient. As Remer was known to be a staunch Nazi, it was suggested by the plotters that he be sent away on duty on the day of the coup, but Hase insisted that Remer would follow orders. On 20 July Remer attended the City Commandant’s office on the Unter den Linden as directed and Hase showed him the area he was to secure. Remer understood and took leave to deploy his troops, who were in place by 1830hrs. However, Remer and his junior officers were already uneasy at what they had been asked to do, sensing that they were being used as part of a Putsch. Leutnant Hagen was particularly suspicious, because he believed he had seen Generalfeldmarschall von Brauchitsch earlier in the day in full uniform (Brauchitsch was a former army commander-in-chief) and asked Remer at around 1700hrs if he might speak to Goebbels to gain clarification of the situation. Remer agreed; he had, after all, complied with his orders, and Goebbels was honorary colonel of Remer’s unit.

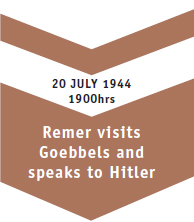

Hagen was duly seen by the propaganda minister and was persuaded of the gravity of the situation – troops were visible on the streets. Goebbels asked Hagen to invite Remer to see him to discuss the matter. Initially Hagen could not find Remer, but eventually he got word to him of the invitation. Unsure of who held legitimate power, Remer spoke to Hase, who insisted he was acting for the legal regime and that it was unclear where Goebbels stood. Remer was ordered to stay put. He was now torn between orders and a summons from the propaganda minister, and decided to speak to Goebbels, arriving at his office at around 1900hrs. Both parties explained what they knew and swore allegiance to the Führer. Now Goebbels played his trump card and put a call through to the Führer. Remer was given the receiver and asked if he recognized Hitler’s voice. He did. Hitler now instructed him to deal with the insurrection until Himmler, as the new commander-in-chief of the Replacement Army, arrived.

Remer now ordered the troops who were guarding the government quarter to gather in the garden of Goebbels’ residence, where the propaganda minister addressed them. He explained what had happened and Remer confirmed that he had personally been directed to crush the coup. Men of Wach-Bataillon ‘Grossdeutschland’ were redeployed to protect the area around the Propaganda Ministry, while others were positioned on key routes into the city to intercept units heading into the capital.

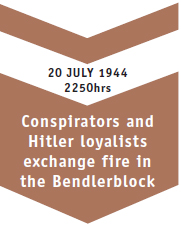

Oberleutnant Rudolf Schlee, commanding the troops protecting the Bendlerblock, was briefed on developments and it was made clear to him that only orders from Major Remer were to be obeyed. This direction ran counter to orders emanating from the building behind, and Schlee asked to speak to Olbricht. Olbricht was not available so he spoke instead to Mertz von Quirnheim, who insisted he was not to follow Remer’s orders. Mertz von Quirnheim now retired to brief Olbricht on this serious development, and Schlee took the opportunity to slip out of the building. It was clear something was amiss and his suspicions were confirmed by another officer inside the building; the leaders of the coup were in the Bendlerblock. Schlee passed this news to Remer who was with Goebbels. The propaganda minister immediately phoned Hitler who directed that Remer’s unit round up the conspirators. On returning to the Bendlerblock, Schlee secured all the entrances and prepared to enter the building. However, within the building ‘loyal’ German officers had now begun to take matters into their own hands.

The Propaganda Ministry as it looks today. On 20 July 1944 Goebbels was in residence and in the evening it was surrounded by Major Remer’s troops as part of Operation Valkyrie. In this building Remer took a call from Hitler and afterwards marched on the Bendlerblock to arrest the conspirators. (Amy Short)

At 1242hrs on 20 July an explosion had ripped through the briefing room at the Wolfsschanze where Hitler was being informed about developments on the Eastern Front. The reverberations of the bomb blast spread from the forests of East Prussia to all parts of the Reich, but now, as night came on, the coup everywhere began to implode.