The shots that rang out in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock in the early hours of 21 July signalled not the end, but the beginning of the bloodletting. Investigations led by the RSHA uncovered more and more names associated with the conspiracy. Many of the officers identified were from the old ruling class and some in the Nazi Party saw this as an opportunity to eliminate the traditional elites. Robert Ley, the leader of the DAF, spoke of ‘blue-blooded swine whose entire families must be wiped out’ (quoted in Grunberger 1974: 189), while Goebbels, who was unusually restrained, simply issued directives for the post-war liquidation of the aristocracy. Hitler was similarly outraged and wanted revenge, but ordered them to desist with such rhetoric; he insisted on a more measured approach. The conspirators would be tracked down by SS-Obergruppenführer Kaltenbrunner, the RSHA chief, and SS-Gruppenführer Müller, the head of the Gestapo.

Entrance to the Alter Sankt Matthäus Kirchhof. On the night of 20/21 July, Fromm ordered the bodies of Beck, Olbricht, Stauffenberg, Mertz von Quirnheim and Haeften be taken here and buried with full military honours. The cemetery is the resting place of the Brothers Grimm and other notable Germans, though the conspirators were not to rest in peace there for long. (Author)

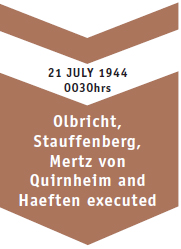

Yet although Himmler and Kaltenbrunner were sent to Berlin immediately after the bombing to start their investigation, some of the conspirators had already escaped the net. Stauffenberg, Olbricht, Haeften and Mertz von Quirnheim had been summarily shot and Beck had taken his own life. General der Artillerie Wagner also committed suicide, as did Major von Oertzen, who had transmitted the Valkyrie order. He had been detained soon after the plot, but had been released and went home, where he killed himself just as the Gestapo arrived to re-arrest him.

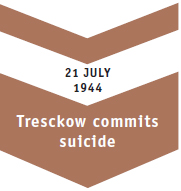

On the Eastern Front, Tresckow heard the news of the coup’s failure from his aide Schlabrendorff. Convinced that he would be identified as one of the conspirators, he explained that he would take his own life in order not to incriminate anyone else under torture. Schlabrendorff tried to dissuade him but Tresckow was not for turning. He made his way to the front and committed suicide. When his body was recovered it was assumed he had been killed by the enemy and his body was taken back to Germany to be buried. Later his role in the plot was uncovered and his body was exhumed and taken to the crematorium of Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

In France, Stülpnagel, whose role in the plot had been exposed to those in the Wolfsschanze by Kluge, was recalled to Germany. Understanding the meaning of this order he set off, but stopped en route near Verdun where he had served in World War I. He slipped away from his staff with his pistol with the intention of killing himself, but the head shot was not fatal and only served to blind him. He was rescued by his aides and treated in hospital. Meantime, Kluge’s treachery meant he initially escaped suspicion, but on 17 August he was relieved of his command after apparently trying to contact the Allied High Command. On his way back to Germany he followed much the same route as Stülpnagel, the man he had betrayed. He too took a break on the journey near Verdun and swallowed a poison capsule, which proved more effective than had Stülpnagel’s pistol.

Those involved in the trial of the 20 July plotters give the Nazi salute. Nearest the camera is Volksgerichtsrat Paul Lämmle. In the centre is the president, Roland Freisler, and to his right is General der Infanterie Hermann Reinecke, head of the Allgemeines Wehrmachtsamt. (Topfoto)

Those officers who decided not to take their own lives presumably believed that if they were arrested they would come before a military court. But Hitler was determined that they would not be tried by their own kind and instead would appear in the Volksgericht or People’s Court. Thus officers suspected of disloyalty were hunted down and arraigned before a military tribunal. These were headed by officers chosen by Hitler and included Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, Keitel and Guderian. In the first hearing 22 senior officers were discharged from the army, including Witzleben, Hoepner, Hase and Stieff. Stripped of rank they were tried on 7 August in the People’s Court by Judge-President Roland Freisler, who sought to demean them at every turn. Witzleben was particularly harshly treated; his false teeth were removed and his belt and braces were confiscated so that he had to hold his trousers up with his hands. The proceedings were filmed and shown to public audiences in an effort to ensure similar treasonable acts were not repeated. The four were sentenced to death by hanging and sent to Plötzensee Prison, where the sentence was to be carried out. On 8 August these four and four others were strung up on meat hooks until they died. The whole episode was photographed for the Führer. Two days later, Fellgiebel and Stauffenberg’s older brother Berthold was executed in the same way.

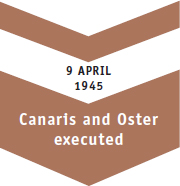

Schlabrendorff, who had tried to dissuade Tresckow from taking his own life, was arrested and sent to Gestapo headquarters in Berlin, where he was incarcerated with Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, former director of the Abwehr; Hans Oster, Canaris’s chief of staff; Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, former mayor of Leipzig; and the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Schlabrendorff suffered terrible torture but bravely resisted, implicating only Tresckow, who was now safe from the Gestapo. His resilience saved his life. Not until February 1945 did Schlabrendorff appear before the People’s Court and, as luck would have it, his case was interrupted by an air raid. Everyone made their way to the shelters except for Freisler, who went back to get Schlabrendorff’s file, which was still in the courtroom. At the same time the building was hit by a bomb and Freisler was killed – an example of divine intervention if ever there was one. The case was adjourned and when it was reconvened Schlabrendorff was acquitted. He was later re-arrested, but survived the war.

Generalfeldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben, now stripped of his army uniform and rank, appears at the People’s Court in August 1944. To further embarrass Witzleben, his belt and braces were removed so forcing him to hold his trousers up. He was found guilty and executed on 8 August 1944. (Topfoto)

Canaris, Oster and Bonhoeffer were not so lucky. After months of torture they were killed in Flossenbürg concentration camp on 9 April as the SS guards, in one last orgy of violence, ‘cleansed’ the facility before US troops arrived. Goerdeler was hanged in February and was one of the many civilians to perish. A number of the so-called Kreisau Circle, who sympathized with the conspirators, were also executed, including the leader of the group Helmut von Moltke and the diplomat Adam von Trott zu Solz. Even those unassociated with the plot were not immune, such was the paranoia: ‘During the wave of persecution that followed the Officers’ Plot, an Evangelical deaconess was executed for describing Himmler, the newly appointed C-in-C of the reserve army [Replacement Army], as “a man of simple background not sprung from the soldierly estate”’ (Grunberger 1974: 189).

But it was the officer class that suffered the greatest retribution. Having recovered sufficiently to face trial, Stülpnagel went before the People’s Court on 30 August, along with other senior officers in France including Stauffenberg’s cousin, Oberst Cäsar von Hofacker. All had resolutely defied their torturers and, indeed, Hofacker led a spirited defence in his trial, but this simply resulted in a further term in prison. During this time he revealed, under duress, a conversation he had with Rommel about impressing on Hitler the need to end the war. This confession, together with other evidence, brought into question Rommel’s loyalty. The days of the Desert Fox were now numbered; it was simply a question of whether he would be executed or would die by his own hand.

A close-up of the special beam that was inserted in the execution room in Plötzensee Prison. The beam is fitted with a series of hooks and from these the condemned were hanged, including Generalfeldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben, Generaloberst Erich Hoepner, Generalleutnant Paul von Hase and Generalmajor Helmuth Stieff. (Author)

The decision of a number of the conspirators to commit suicide and the silence of others, in spite of lengthy and brutal torture, meant that a number of individuals escaped punishment. Generalleutnant Adolf Heusinger, who had been at the 20 July briefing, was arrested but not tortured and, with no concrete evidence of involvement in the plot, he was released. He survived the war and later became a senior figure in NATO. Generalmajor Hans Speidel, Rommel’s chief of staff, was also arrested but with help from Guderian was released and, like Heusinger, became a top NATO commander after the war.

Both Heusinger and Speidel were dismissed and these departures, along with the executions, left yawning gaps in the senior ranks of the army. Hitler acted quickly to fill these vacancies. Guderian retained the job of Inspector General of Armoured Forces but additionally became Chief of the Army General Staff, replacing Generaloberst Kurt Zeitzler, who had left the job in early July due to nervous exhaustion. His promotion, however, was due more to his loyalty to Hitler than his skill as a commander. Although he was a gifted tactician and had been instrumental in the development of Blitzkrieg, he was no strategist. As such he was little more than a figurehead; a mouthpiece for Hitler. In France, Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model replaced Kluge, but at the end of August Rundstedt returned to take command of Heeresgruppe D (Army Group D); Model retained command of Army Group B. Generalmajor Wilhelm Burgdorf was promoted Generalleutnant and made head of the Army Personnel Office following the death of Schmundt.

The memorial at Plötzensee Prison to those who died at the hands of the Nazis. Today Plötzensee is still a working prison but this part has been isolated and houses the memorial and a small exhibition. (Author)

Lackeys like Jodl and Keitel – whose nickname was Lakeitel12 – retained their place in the inner circle. Indeed, such was their blind obedience to the cause that after the event Keitel was ‘incapable of recognizing the conflict in which the conspirators of 20 July 1944 find themselves, and saw there nothing but injured pride, frustrated ambition and office-seeking! When Rundstedt was asked in Nuremberg whether he had never thought of getting rid of Hitler, he replied firmly and unhesitatingly that he was a soldier, not a traitor’ (Fest 1979: 368). In spite of this unwavering loyalty, the conspiracy undoubtedly heightened Hitler’s mistrust of the army and increasingly he surrounded himself with officers from the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe, regardless of the fact that these arms of the Wehrmacht played little or no part in the fighting at the end of the war.

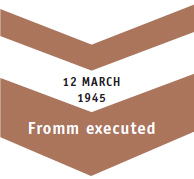

The power of the SS also grew. Himmler was appointed as commander of the Replacement Army superseding Fromm, who had been expelled from the army in September 1944 and who was executed in March 1945 for cowardice – no evidence was provided for his complicity in the plot. Himmler was now responsible for raising new formations, mostly Volksgrenadier-Divisionen. The prefix ‘Volk’ was deliberate and was designed to differentiate the new units from established army units commanded by the old officer corps. These new divisions were administered by the SS and only officers approved by the SS could serve in these units. However, such were the shortages of suitable candidates that officers were removed from the army and posted to the SS, often against their will, in order to fill technical posts that no one in the SS had the skills to do.

However, although Himmler gained powers, paradoxically, he lost influence, because the new roles took him away from the Führer. In his absence questions were asked about Himmler’s competence. He was after all the head of security, which had failed to uncover the 20 July Plot. The true winner in the power struggle that developed after the 20 July Plot was Martin Bormann. As Hitler’s private secretary he was continually at the Führer’s side. He controlled the party and access to Hitler. Goebbels still retained his position, and Bormann knew better than to argue with him, but Bormann had ‘achieved an undisputed supremacy such as had never been previously known in the immediate entourage of his master’ (Trevor-Roper 2002: 32).

In this power struggle Göring became an increasingly peripheral figure and, in an effort to curry favour, Keitel and he, as heads of their respective services, suggested that the military salute be replaced by the Nazi salute and a ‘Heil Hitler!’ The idea was presented as being ‘the desire and the demand of all Services …’. Göring went on to suggest that it was an ‘indication of unshakeable loyalty to the Führer and of the close bonds of comradeship between Wehrmacht and Party’ (Warlimont n.d.: 442). The change was instituted on 23 July 1944 and woe betide anyone who failed to follow the new order. General der Panzertruppe Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, the defender of Monte Cassino, was criticized for not making the ‘German Greeting’. This was symptomatic of a wider unease that permeated the army after 20 July. Officers suspected of disloyalty were condemned by political officers (NSFOs) in the Wehrmacht. Indeed, an anonymous complaint from someone with a grievance was often sufficient for an officer to be reduced to the ranks, or worse. This terror continued until the end of the war and, as such, the officer corps was decimated at a time when it needed to be maintained to cope with the military emergencies engulfing the Reich.

The attack on the army went further. On 24 July an order was issued that stipulated that, before an officer could be posted into a new job, he and his family should be vetted. A week later, on 1 August, the so-called Sippenhaft (literally, kin liability) was introduced. This meant that families of personnel in the armed forces were held personally responsible for their actions. If their menfolk did not do their duty then their relations could be imprisoned or executed. This would ensure that men at the front would obey orders, no matter how futile.

For Hitler, then, the conspiracy offered an opportunity to destroy his enemies and re-establish his authority over the army. At the same time, this treachery was used to explain military reverses that might otherwise have been blamed on Hitler. But while Hitler had taken the opportunity to turn this attack to his advantage, it came at a cost. The explosion on 20 July had killed stenographer Dr Heinz Berger and, on 22 July, General der Flieger (literally, General of the Flyers) Günther Korten and Oberst Heinz Brandt also died. Ironically, the latter was a resistance sympathizer. On 1 October Generalleutnant Schmundt died as a result of the injuries he received. Perversely, those injured in the blast were awarded a special wound badge with a 20 July 1944 inscription.

Hitler himself had escaped from the briefing largely unscathed. However, as time passed it was clear that the blast had taken its toll on the Führer’s health. Both his eardrums had been perforated, which affected his hearing and his balance. The right ear continued to bleed and had to be cauterized. His right arm was still painful, made worse by Morell’s treatment, which made shaking hands or even signing documents difficult. Headaches kept him awake at night and he was prescribed cocaine, which relieved many of his symptoms. However, somewhat unusually, the blast did seem to have cured Hitler’s tremor, at least in the short term.

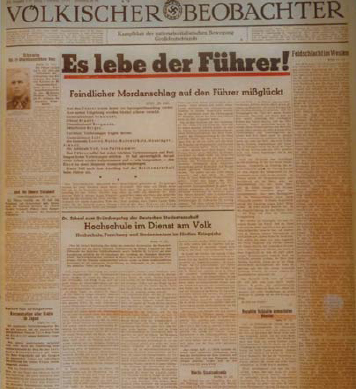

The headline in the Völkischer Beobachter, the official Nazi newspaper, on the day after the coup attempt. It reads ‘Long Live the Führer – Unsuccessful assassination attempt on the Führer by hostiles’. (Author)

The bomb attack also heightened Hitler’s paranoia, and precautions were taken to prevent a repeat. An investigation undertaken by the RSHA concluded that the previous security precautions could not prevent a general staff officer who had been invited to deliver a brief from an assassination attempt. After 20 July, officers were frisked and no weapons could be brought into briefings. Briefcases were checked, much to Warlimont’s chagrin, and in the end he stopped bringing one. After being checked for bombs, the filter system in Hitler’s bunker was overhauled along with the back-up oxygen system to ensure they were fit for purpose. Both were in need of improvement and more cylinders of oxygen were supplied to allow 30 days’ use. To prevent poisoning, Hitler’s food was now tasted.

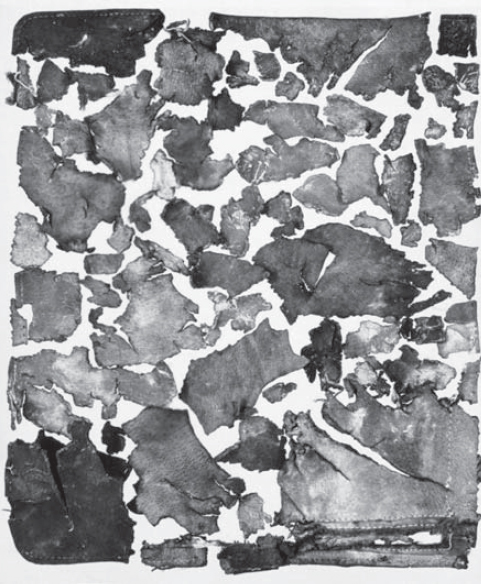

The cause of the blast was initially unclear. However, it soon became apparent that explosives had been used. The remains of Stauffenberg’s briefcase were recovered from the shattered briefing room and pieced together. (NARA)

Security was also tightened in the headquarters. Immediately after the blast FHQ Wolfsschanze was swamped with SS personnel. Elements of the SS-Leibstandarte ‘Adolf Hitler’ arrived on the night of 20/21 July and occupied key points. Their presence, however, caused friction with the normal security personnel and eventually they were withdrawn. But it was clear that changes needed to be made and so more SS and RSD personnel were stationed in Sperrkreis I. Traudl Junge complained that ‘There were barriers and new guard posts everywhere, mines, tangles of barbed wire, watchtowers. The paths along which I had walked my dog one day would suddenly be blocked the next with a guard wanting to see my pass’ (Junge 2004: 146). There was also a shake-up in the command structure at FHQ Wolfsschanze. Major, now Oberst, Remer, who had shown his undivided loyalty to the Führer in Berlin on 20 July, was made responsible for security inside and outside the headquarters. Oberst Streve was effectively demoted and was now only camp commandant. All the headquarters troops he had commanded were transferred to Remer. Hitler opined, ‘How thankful I am to Remer … a few more fine, clear-thinking officers like him and I wouldn’t have to worry about the future’ (quoted in Irving 2002: 712).

12 From the German Lakai – lackey.