AND GOD SAID, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark seasons and days and years, 15and let them be lights in the expanse of the sky to give light on the earth.” And it was so. 16God made two great lights—the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night. He also made the stars. 17God set them in the expanse of the sky to give light on the earth, 18to govern the day and the night, and to separate light from darkness. And God saw that it was good. 19And there was evening, and there was morning—the fourth day.

20And God said, “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the expanse of the sky.” 21So God created the great creatures of the sea and every living and moving thing with which the water teems, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind. And God saw that it was good. 22God blessed them and said, “Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the water in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth.” 23And there was evening, and there was morning—the fifth day.

24And God said, “Let the land produce living creatures according to their kinds: livestock, creatures that move along the ground, and wild animals, each according to its kind.” And it was so. 25God made the wild animals according to their kinds, the livestock according to their kinds, and all the creatures that move along the ground according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good.

26Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, in our likeness, and let them rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, over the livestock, over all the earth, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

27So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.

28God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”

29Then God said, “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food. 30And to all the beasts of the earth and all the birds of the air and all the creatures that move on the ground—everything that has the breath of life in it—I give every green plant for food.” And it was so.

31God saw all that he had made, and it was very good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the sixth day.

Original Meaning

THUS FAR WE have argued that Genesis 1 is not the record of the creation of physical matter but a divine organization and assignment of functions to the cosmos. Days four, five, and six fall in line with this same overall theme, but turn attention to the functionaries.

Day Four (1:14–19)

FUNCTIONS. The functions of the celestial bodies mentioned in the text indicate that they are “signs to mark seasons and days and years.” Contrary to the NIV translation, the word “signs” does not govern the other words but is an independent item.1 Signs function theologically in the Old Testament as indicators through which God conveys knowledge and reveals himself. They can be used for warning, motivation, and authentication.2 An eclipse would be an example of the heavenly bodies being used for a sign. What is most important is that this function is not simply of a mechanical nature but assumes God’s using the heavenly bodies.

The second function indicates that the celestial bodies serve for identifying moʿ adim, which the NIV, along with many others, translates “seasons.” W. Vogels has demonstrated, however, that throughout the Pentateuch as well as in most other contexts, the moʿ adim are not seasons such as summer and winter but are more specifically the related festivals and religious feast days of the liturgical calendar.3 Again this is more than a mechanical function; it is a socioreligious function.

The third and last function in the list indicates that the celestial bodies are “for days and years.” This is one function, not two, because the preposition “for” (le) is not repeated. The positions of the sun, moon, and stars served as the foundation for calendrical calculations in the ancient world. The idea is not that they simply marked the passage of time but that the calendar was established through celestial observations. The cycle of the moon established when months began and ended. The stars helped to calculate the solar year and to make periodic adjustments to the calendar to synchronize the lunar calendar with the solar calendar. This was essential because a strictly lunar calendar would eventually skew the agricultural (and therefore cultic) seasons.

This functional approach, which we saw in previous sections, is once again mirrored both in biblical and in Mesopotamian literature regarding the celestial bodies. In a prologue to a Sumerian astrological treatise, the major gods (An, Enlil, and Enki) put the moon and stars in place to regulate days, months, and omens.4 The famous Babylonian Hymn to Shamash, the sun god, also refers to his role in regulating the seasons and the calendar in general. It is intriguing that he is also the patron of divination.5 The Hebrew word used for “sign” has a cognate in Akkadian that is used for omens, though it has a more neutral sense in Hebrew. Once again the author has emptied the elements of the cosmos of their more personal traits, as he did with the elements of chaos in verse 2.

Another noticeable attempt to neutralize any presumed personality comes in the use of the generic word “lights” instead of referring to the sun and moon by name. It has been frequently pointed out that the Hebrew words for “sun” and “moon” also served as the names of deities connected with the sun and moon in the neighboring cultures. By refraining from the use of those names, the author has left no room for the idea that gods were being brought into existence. On the other side of the equation, we cannot assume that this choice was motivated purely by polemics (after all, the text did not hesitate to use the equally confusing tehom when referring to the sea in v. 2). Given the way the text frequently refuses to attack the ancient Near Eastern views directly, we may refer to their approach as passively polemical.

The Hebrew word translated “lights” (meʾorot) is not used frequently (19× in its various forms). Most occurrences are in the Pentateuch (15×), with the remainder in Psalms (2×), Proverbs (once), and Ezekiel (once). The occurrences outside the Pentateuch speak either of the celestial bodies or metaphorically of the face or eyes that shine. What is intriguing is that the ten occurrences in the Pentateuch outside of Genesis 1 (Ex. 25:6; 27:20; 35:8, 14[2×], 28; 39:37; Lev. 24:2; Num. 4:9, 16) all refer to the light of the lampstand that lights up the tabernacle. The use of the word “lights” may then be our first clue that there is another whole dimension to this text that has often eluded us: the description of the cosmos as a temple or sanctuary of God.6 This will be further explored and developed in the next chapter.

What did God do on day four? In verse 16 the NIV translates, “God made two great lights.” The Hebrew verb for “made” here (ʿśh) has a wide range of meanings. It is usually listed in the lexicons with the primary meaning of “to do or make,” but that is only the tip of the iceberg. So, for instance, one current lexicon used in scholarly circles, the third edition of Koehler-Baumgartner (Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament), lists no fewer than sixteen meanings for the Qal form alone. It is clear from the profile of usage that “manufacture” is one of the possible nuances. HALOT also lists “create,” “prepare,” and “make ready”—all supported by select passages. The interpreter must ask which of these meanings approximates what the author wanted to say (not which of the many meanings best fits my theory or beliefs).

The significance of this goes far beyond an understanding of the fourth day because Exodus 20:11 asserts that “in six days the LORD made [ʿśh] the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them” (cf. a similar statement in Gen. 2:3). Is this saying that the Lord manufactured all of these things in these six days, and that he manufactured the heavenly bodies on Day Four, or does he intend one of the other various meanings? Perhaps we can approach an answer to this by investigating how the verb is used and with what objects in cosmological contexts.7

1. Job 9:9 shows us that the verb does not always refer to tangible scientific realities. Constellations are not objects, they are arrangements of stars. Thus ʿśh can be used in cosmological statements to refer to actions such as arranging rather than manufacturing.

2. Isaiah 41:17–20 demonstrates that even when the objects of the verb are cosmological in nature, the action is more functional in nature. Both verbs ʿśh and brʾ are used to describe this establishment of functions, showing that the former can pick up the functional bent of the latter in cosmological contexts. This overlap is also seen in Genesis 1:26 (ʿśh) and 27 (brʾ ).

3. Isaiah 45:7 uses a variety of verbs (including both ʿśh and brʾ ) and includes primarily nonmaterial objects in a cosmological statement. The thrust is functional in nature and, most significantly, the whole series is summed up using ʿśh.

4. For other interesting functional uses of ʿśh, see Jeremiah 38:16 (life), 1 Kings 12:32–33 (feast), and especially Exodus 34:10 (where both ʿśh and brʾ are used with miracles as the object).

It is significant that though there are numerous ambiguous usages, no passage using ʿśh in a cosmological context demands the meaning “manufacture” rather than something more functional. On the basis of these passages, there is good reason to conclude that the author of Genesis is using the term functionally. It is indefensible to claim that the use of ʿśh demands that the heavenly bodies are manufactured on day four. Usage in cosmological texts favors taking ʿśh in verse 16 as a summary of the setting up of functions for the heavenly bodies as reported in verses 14–15. In relation to Exodus 20:11, we can say that in six days God did all his business, without necessarily defining that business as manufacture of matter.

As a result of our modern tendency to focus on things and to view creation as the making of things, it is not a surprise that when we ask, “What did God do on the fourth day?” we look around for him to make something. Sailhamer accurately picks up the text’s interests when he notices the consistent emphasis on God speaking.

What the writer wants most to show in this narrative is not that on each day God “made” something, but that on each day God “said” something. The predominant view of God in this chapter is that He is a God who speaks. His word is powerful. As the psalmist who had read this chapter said, “By the word of the Lord the heavens were made” (Psalm 33:6). Thus, often when God speaks, he creates. But that is not always the case in this chapter.8

God speaks, and the result of his proclamation is that the celestial bodies are assigned their functions in this newly operational cosmos.9 The concept of creation taking place through the speech of deity is not emphasized in Mesopotamian cosmological thinking, but it is prominent in some Egyptian traditions. In the Memphite Theology particularly, the god Ptah creates by means of the spoken word.10 S. Morenz explains the function of this concept in Egyptian thinking in terms of the relationship between word and object:

The mouth which “pronounced the name of everything” (l.55) was thought capable of really creating things; on the other hand, things do not exist unless they are named, and thus the primeval condition may be termed “when the name of anything was not yet named.” Secondly we must realize that in a sacrosanct monarchy people automatically carried into effect the commands given to them—and it was a command that issued forth from the god’s tongue in our text.11

This reasoning is not contrary to biblical thinking or to orthodox theology. In fact, there are interpreters who, though unaware of the Egyptian material, have proposed that the proclamations of the six days are proclamations only. A. Hayward argues that the follow-up statements (i.e., the ones following the “it was so” statements in vv. 12, 16, and 25) record the follow-up activity that carried out the commands and actually occurred over a long period of time after the seven days of proclamation and naming had been completed.12 While I would not endorse that view as supported by the syntax and grammar of the text or as the intention of the author, it illustrates how central a role the proclamations play. Just as the gods of the ancient world set destinies in the cosmos by decree, so Yahweh established order and function by his spoken word. The text does not address how or when the bodies originated; rather, the assignment of function is described in the text by the verb ʿśh.

The report of the fourth day concludes with the presentation of other functions of the heavenly bodies: giving light, and dividing and ruling over the day and night.

Day Five (1:20–23)

THE CREATURES OF the sea in verse 21 draw special attention for two reasons. (1) They represent a specialized subgroup of creatures singled out of the generic crowd. (2) The text comes back to the word brʾ (create), which it has not used since verse 1. While we may be inclined to identify these creatures as whales, sharks, and the like, that is not what the Hebrew word (tannin) would have communicated to its audience. Other uses of this word associate it with the chaos monsters that were believed to inhabit the cosmic waters. So, for instance, Psalm 74:13–14 puts Leviathan, a multiheaded beast, in the category of tannin.13

Again the polemic comes to the surface, as these creatures are not antagonists that have to be defeated, but creatures that have been given functions (brʾ ) just like any other. It would be important for a cosmology of the ancient Near East to address the issue of chaos monsters of the sea, especially one such as Genesis that offers a variant view of the cosmos.

As living creatures are put in place on days five and six, the blessing of being fruitful and multiplying indicates that their proliferation is not intended as a scourge on humankind.14 In fact, they were created to be subservient to people. These statements address the concept of jurisdiction and breeding that touch on the role and operation of these classes of creature (note, not species). Though humans exercise rule over the animals in general, the fish and birds occupy a different realm, sea and sky, where they carry out their functions.

In 1:20 is the first occurrence of the designation nepeš ḥayya (NIV “living creatures”). The same designation is used for land animals in 1:24 and includes some sea creatures and birds in 1:28; in 2:7 it indicates what Adam became when God breathed into him in 2:7. Though people will be differentiated from the animal world by the image of God, they hold in common with all creatures the quality of life.

Day Six (1:24–31)

ANIMALS. Rather than differentiate animals by phyla and species as we are inclined to do, the categories are divided into domesticated animals (behema), wild herd animals that often serve as prey (remeś), and wild, predatory animals (ḥayya).15 These inhabit the region of the dry land, and the earth “brings them forth” in the same way that the earth “brought forth” vegetation in verse 12. In keeping with the functional emphasis, this does not describe a biological process but a functional relationship.

Use of plurals. The use of the plural pronouns (“us” and “our”) in verse 26 has occasioned constant discussion among the commentators. The early church fathers considered them a reference to the Trinity, while the rabbis offered various grammatical explanations. In the last century, two other theories have arisen, which explain the plural as a vestige of polytheistic mythology or as a reference to a heavenly court. Thus, there are now three categories of explanation:

1. Theological: The plurals are explained as an expression of plurality within the Godhead, either specifically of the Trinity or at least as a recognition of the two persons represented by the creator God (ʾ elohim) and the Holy Spirit of verse 2.

2. Grammatical: The plurals are explained as an expression of grammatical or rhetorical conventions, including self-deliberation, plural of majesty, and grammatical agreement with the plural ʾ elohim.

3. Cultural: The plurals are explained against the background of ancient Near Eastern culture.

We do not have the space to consider each of these in the detail they deserve, but in the end, it is methodology and presupposition that lead the interpreter into one category or another. The grammatical is the easiest to dismiss since none of the cited conventions are attested with any consistency in Hebrew. The rare instances in which they can be claimed generally have either other possible explanations or characteristics that differentiate them from the usage here.

The theological is probably the most popular in traditional circles, but it suffers when subjected to hermeneutical cross-examination. That is, if we ask what the Hebrew author and audience understood, any explanation assuming plurality in the Godhead is easily eliminated.16 If the interpreter wishes to bypass the human author with the claim that God’s intention is what is important, there are large obstacles to hurdle. If the divine intention is not conveyed by the human author, where is it conveyed? Certainly if the New Testament told us that the Trinity was referred to in this verse, we would have no trouble accepting that as God’s intention. But it is not enough for the New Testament simply to affirm that there is such a thing as the Trinity. That affirmation does not prove that the Trinity is referred to in Genesis 1:26. Without a specific New Testament treatment, we have no authoritative basis for bypassing the human author.

Further commending the human author is the belief that the Old Testament audience also had an authoritative text being communicated to them. We cannot afford to approach the text with the question, “Which interpretation fits best with my beliefs?” We must ask what the plurals would have meant to the original audience. That leads us to the cultural category.

One of the cultural options taken by interpreters is that the plurals are a vestige of polytheism. Unfortunately, they can only accommodate their view by means of many presuppositions concerning the derived nature of the text and the incompetence of a series of editors. Since most readers, like myself, are not persuaded in the least by those presuppositions, we will simply set that option aside.

The other position informed by cultural background, the heavenly court option, is much more defensible in that the concept of a heavenly court can be shown to be current not only in the ancient worldview, but also in the biblical text.17 Thus, the belief in such a heavenly court does not need to be imported from the general culture (though the evidence for it is extensive and clear);18 one needs only read the Bible. In the ancient Near East the heavenly court was a divine assembly made up of the chief gods of the pantheon. It was this group that made decisions and decreed destinies. In the Old Testament, the heavenly court is made up of angels, or more specifically, the “sons of God.” All that remains is to consider whether the details of the context are in accord with what we know of God and his heavenly court.

Some have objected that it denigrates God to suggest that he consults with angels about such matters (Isa. 40:14). They point out, in addition, that it is contrary to biblical teaching to think of the angels being involved in creation or of people being in the image of angels. Careful reading, however, demonstrates that these objections cannot be sustained. (1) We must distinguish between consulting and discussing. God has no need to either consult or discuss with anyone (as Isa. 40:14 affirms). (2) It is his prerogative, however, to discuss anything he wants with whomever he chooses (Gen. 18:17–19). Such inclusion of the heavenly court in discussion does not in any sense necessitate that angels must then have been used as agents of creation. In Isaiah 6:8 the council’s decision is carried out by Yahweh alone. (3) Finally, the idea that the image should be referred to as “our” image does not imply that humans are created in the image of angels; it is possible, though not necessary, that angels also share the divine image in their nature. The image of God differentiates people from animals, not from angels.

If, then, we are going to link our interpretation to the sense that the Israelite audience would have understood (and methodologically I believe that is essential for maintaining the authority of the text), the heavenly court is the most defensible interpretation and poses no insuperable theological obstacles.

Image of God. The image of God is an important theological concept both in Old and New Testaments, with roots that extend back into ancient Near Eastern thought. In the ancient world an image was believed in some ways to carry the essence of that which it represented. An idol image of deity, designated by the same terminology used here, was used in worship because it contained the deity’s essence. This does not suggest that the image could do what the deity did or that it looked the same as the deity (even though the idol was a physical object). Rather, the deity’s work was thought to be accomplished through the idol. The Hebrew word ṣelem (“image”) is a representative in physical form, not a representation of the physical appearance.

In Mesopotamia a significance of the image can be seen in the practice of kings setting up images of themselves in places where they want to establish their authority. Other than that, it is only other gods who are made in the image of gods. Thus, their traditions speak of sons being in the image of their fathers19 but not of human beings created in the image of God. In Egyptian literature, the Instruction of Merikare identifies humankind as the god’s images who came from his body.

Well tended is mankind—god’s cattle

He made sky and earth for their sake . . .

He made breath for their noses to live.

They are his images, who came from his body . . .

He made for them plants and cattle,

Fowl and fish to feed them . . .

When they weep he hears . . .

For god knows every name.20

Generally Egyptian usage refers to the king as being in the image of deity, not as a physical likeness but related to power and prerogative.

In ways similar to the above information, the governing work of God is seen in Genesis to be accomplished by people (1:28). But that is not all there is to the image of God. Information from other contexts that can be gleaned about the image includes that (1) the image of God is not lost at the Fall (9:6), though it must be somehow hampered or reduced, else it would not need to be restored; and (2) it does differentiate people from animals (9:6), though that does not mean that anything that differentiates is part of the image.

Perhaps most significant, 5:1–3 likens the image of God in Adam to the image of Adam in Seth. This goes beyond the comment about plants and animals reproducing after their kind, though certainly children share physical characteristics and basic nature (genetically) with their parents. What draws the idol imagery and the child imagery together is the concept that the image of God in people provides them the capacity not only to serve as God’s vice-regents (his representatives containing his essence), but also the capacity to be and act like him. Thus, 5:1–3 is perhaps the most significant for determining how we ought to interpret the image of God.

While a baby may be affirmed to be in the image of its father, few can recognize that image. Based on the inherent image and the relationship with the father, the image grows more recognizable as the child matures. This does not essentially take place in a physical way, but rather in the way the child mirrors the attitudes, expressions, and character traits of his or her father. The biblical text, by offering us this explanation, gives us the key that while we are all in the image of God, we likewise have the capacity to become more and more in the image of God; that is, we were created with the potential to mirror divine attributes.

We might deduce that reason, conscience, self-awareness, and spiritual discernment are the tools he has provided so that we may accomplish that goal rather than actually defining the image. It is only because God has given us these that we have the capacity to develop the image from its germ form. This is certainly in line with the New Testament perspective, as redemption, sanctification, and eventually glorification all serve as additional factors to refine the image of God in us (Eph. 4:24; Col. 3:10).

In conclusion, the following definition takes account of all of the ancient Near Eastern and biblical evidence concerning the role of the image of God: The image is a physical manifestation of divine (or royal) essence that bears the function of that which it represents; this gives the image-bearer the capacity to reflect the attributes21 of the one represented and act on his behalf. Note the similarity of this idea with New Testament statement concerning Christ being “the image [eikon] of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15). He is a physical representative of God rather than a physical representation of what God looks like. As such he bears the essence of God, reflects his attributes, and acts on his behalf. In the context of Genesis 1, people act on God’s behalf by ruling and subduing.

The blessing. While the image of God defines a role for humanity (vice-regents for God), the blessing indicates the functions that people will have as a result of the role to which they were created. The first function is to “subdue” (kbš) the earth, the second to “rule” it (rdh, the same as used in v. 26, but different from the verb used in vv. 16–18, mšl). In its biblical usage the first word is usually employed in political contexts but is also found sociologically (with objects such as women and slaves). Genesis 1 is the only occurrence with “the earth” as an object. The profile is pretty clear, however, and is applicable to this context. The term kbš means to bring something or someone under control.22

Is the second verb (rdh, rule) the end result of that process, or is it only one part of it? If it is the end result, then “subdue” refers only to the animal kingdom23 and implies something like domestication. If it is only one part, then “subdue” includes utilization of natural resources (e.g., in the ancient world, mining), harnessing of the earth’s energy (e.g., irrigation), and so on. The occurrence of the feminine singular pronominal suffix on the verb kbš suggests that all of the earth is the object of subduing, not just the animal kingdom. Thus, we can conclude that the animal domestication suggested in rdh is only one part of the process of subduing. The twenty-five occurrences of rdh show that it concerns exercising authority that has been granted or acknowledged.24 It can be used of priests or administrators serving their roles, of kings or tribes dominating others, and even of shepherds exercising authority over their sheep.

Our conclusion, then, is that “subduing” is associated (grammatically, not semantically) with the prior verb, “filling,” and has the earth as its focus. “Ruling” is directed toward the animals and implies domestication or some other level of use or control.25 Of course this does not legitimize slaughter, abuse, or neglect.

Bridging Contexts

ROLE OF FUNCTIONARIES. The fourth day offers one of the clearest evidences of the functional concern of the text. The heavenly bodies are described strictly in terms of what they govern and what role they have. It does not seek to describe how they give light or what relationship they have to the earth in astronomical terms. None of the issues of our scientific cosmology are addressed. The text’s concern is to address how the cosmos is set up to operate.

Over the centuries some of the most remarkable changes in understanding the physical makeup and laws of the cosmos have concerned the perception of the heavenly bodies and how they do what they do. But from the earliest primitive societies to our modern technological age, everyone has understood the impact of the heavenly bodies on the passage of seasons and the importance of the calendar. Here God established the means by which the calendar operates. Despite all of the differences in perception of material structure of the universe over the centuries, there is no difference of opinion regarding how people of different eras and places experience the cosmos. Had the biblical text construed its message in terms of material structure, it would require constant revision. By construing it in terms of function, it communicates clearly to peoples of all ages and eras.

In day four, in other words, the text is still discussing functions. The explicit reference to the function of human beings in verse 26 is likewise appropriate to that kind of thinking. The problem is that there is no obvious connection to function for the creatures of days five and six. The approach that offers an understanding of all three days understands them as discussing functionaries rather than functions. By calling them functionaries, they are identified as carrying out their functions in the respective realm. The celestial bodies (day four) carry out their functions in the sphere of day and night (day one). The birds and the fish (day five) populate the sphere of the sky and the waters (day two). The animals and people (day six) are the denizens of the dry land, with its vegetation serving as their food (day three).

It is not being suggested that these functionaries are the ones that carry out the function of the sphere, only that they populate the sphere and carry out their functions within it. Nevertheless, the emphasis is not on the making of these functionaries as material objects but on setting them up in their respective spheres, playing their roles within the operative cosmos. Sailhamer notes this distinction by drawing attention to the speaking of God.

So if one asks, “Did God do anything on the fourth day?” the answer from the text itself is yes. Just as he did on every other day, God “spoke” on the fourth day. The writer is intent on showing that the whole world depends on the word of God. The world owes not merely its existence to the word of God, but also its order and purpose. It is thus no small matter when the biblical writer shows us that on the fourth day God proclaimed his plan and purpose for creating the celestial bodies. He created them to serve humanity in the day when they began to dwell in God’s land.26

All of the functionaries serve in the cosmos. It is possible to read the text as focusing on all functionaries serving people, but it looks rather that people, while enjoying prominence over some of the other functionaries, are themselves functionaries. They serve God by serving as his representatives in the cosmos. This suggests that the focus of the functionary role is God and his cosmos, not people. The text never suggests that God made it all for us. It only says that he put us in charge of it. Rather, God made it for himself (see further evidence in the next chapter). For now let it suffice to say that the cosmos was not set up to revolve around us but around God.

Human dignity. The recognition that people are mere functionaries must be understood relative to all of the elements of contrast. In our modern worldview people are both nothing (evolved apes) and gods (attested in our individual and corporate self-absorption). In the ancient worldview people were slaves to the gods with no dignity other than that which came from the knowledge that the gods could not get along without humans to meet their needs. Whereas Mesopotamian literature is concerned about the jurisdiction of the various gods in the cosmos with humankind at the bottom of the heap, the Genesis account is interested in the jurisdiction of humankind over the rest of creation as a result of the image of God in which people were created. In the biblical view, it is the concept of being in the image of God that provides for human dignity and the sanctity of human life.

Blessing. First of all, granting a blessing (as in 1:28–30) must be recognized as delineating a privilege, not an obligation. In the ancient world, the ability to reproduce was seen as a gift from God. No one in that world would have considered foregoing the opportunity. It would be inappropriate, then, to consider this as a command that couples must have children.

The blessing likewise does not mandate the filling of the earth. Instead, people are privileged to be able to reproduce without limitation. Ancient texts considered overpopulation a problem. In the Atrahasis Epic overpopulation contributed to the noise of humanity and brought on the Flood. Before the Flood was sent, the gods had tried several other means to try to reduce the population.27 In contrast, Genesis sees being fruitful and multiplying as one of the blessings of God. The filling is not part of the privilege but is the result of the lack of any limitation on the privilege. In other words, they may multiply so that they will fill the earth.

The blessing serves as a foundation for the theological message of Genesis. The genealogies show it being carried out. The Flood shows that as people filled the earth, it filled with violence. And, most important, the covenant becomes an articulation of the blessing as Abraham is promised that from him will come an extensive family.

Perhaps “subduing” and “ruling” can likewise be better thought of in terms of privileges rather than obligations. As such they can be understood as delineating jurisdiction rather than granting some sort of inalienable rights. The subduing applies to the broader world of nature, while ruling is connected by the text specifically to the creatures, encouraging the domestication or control of the creatures that populate the earth. This is an important statement for the biblical writer to make, for jurisdiction in the natural world was regularly granted only to the gods in the cosmologies of Israel’s neighbors. Indeed, one of the principal differences between Israel and her neighbors was in the relationship of the gods to the natural world.

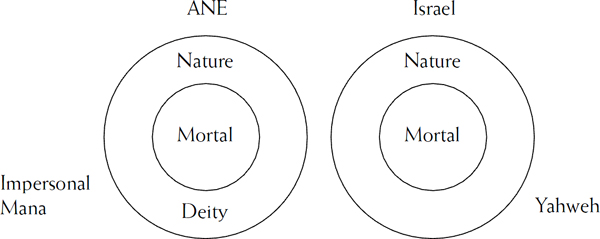

Acknowledging his debt to the observations of Y. Kaufmann, H. C. Brichto has developed a diagram of concentric circles to represent the interrelationships between deity and cosmos in the ancient Near East and Israel:28

In the center circle of Israel’s worldview as well as in the center of the ancient Near East is the world of mortal creatures, including both animals and plants. This inner sphere is subject to restrictions imposed by the other spheres. In the outer circle is the realm of natural powers and laws. They act on the animate world, but they also exist and operate with certain limitations. In Israel this is an impersonal realm, while in the ancient Near East the powers of nature are personified as gods in that the gods are manifest in these powers and carry jurisdiction over them.

Another result of the location of the gods in this second circle is that neither the gods nor corporate deity operate in the unrestricted realm of ultimate power. In Israel, however, that is the realm occupied by Yahweh. He is accountable to no one, dependent on no one, underived, and totally autonomous. In contrast, the realm of ultimate power was impersonal in the polytheistic pagan mentality. This was a realm of magic, where divination and incantations had their focus. At the same time that the Genesis text is distancing itself from the rest of the ancient world by showing God to be the ultimate source of power in the universe and outside of nature, it is showing jurisdiction granted to people in the natural world. Another contrast is that while in the ancient Near East one of the major functions of people was to provide food for the needy gods, Genesis turns it around and has God granting food to people. He is the giver of food, not the receiver of it.

More than anything else, then, subduing and ruling gives people the mission of bringing order to their world just as God has brought order to the cosmos. A. Wolters has identified this as being accomplished through civilization:

People must now carry on the work of development: by being fruitful they must fill [the earth] even more; by subduing it they must form it even more. Mankind, as God’s representatives on earth, carry on where God left off. But this is now to be a human development of the earth. The human race will fill the earth with its own kind, and it will form the earth for its own kind. From now on the development of the created earth will be societal and cultural in nature. In a single word, the task ahead is civilization.29

Contemporary Significance

LIVING IN A WORLD of God’s purpose. We live in an increasingly atheistic society that can brook no consideration of a creation with purpose. People today are more likely to agree with Hemingway’s assessment that life “was all a nothing and a man was nothing too”30 and that people are, therefore, no more than an accident suspended between accidents (birth and death). Limited by material, they have no sense of the eternal.31 This is the world we live in, and its philosophy runs contrary to the biblical view. In earlier chapters we addressed the issues of God’s establishing of the functions of the cosmos. In this chapter we see our role in it all. People are created with functions and purpose. We can do no greater damage to humanity than to rob it of purposeful existence. There is no dignity in being at the top of the evolutionary ladder. We can do no greater damage to biblical theology than to compromise God’s purposeful creation of human beings.

We need to communicate that what is at issue is not the specifics of evolution versus the specifics of Genesis. Rather, at issue is the worldview claim that life is the product of impersonal forces versus the claim that life was designed by an intelligent agent. We must fight worldview with worldview.32

If one were to claim that material objects evolved under God’s purposeful attention, it would be less objectionable than if one were to insist that God created every molecule individually but was indifferent about his purposes. In creation theology, ordaining purpose is biblically more central than making things. Yet too often we have allowed the creation-evolution debate to be staged as if the main issue is the origin of things. We should rather focus on the meaning and purpose of cosmic and human existence.

God’s image. Being made in the image of God confers on us dignity, entrusts us with responsibility, and implants in us a certain potential, namely, the capacity to mirror our Creator. As Christians, our redemption has greatly enhanced this capacity and, in the process, has made us more sensitive to the responsibility we have and the dignity shared by all humankind. We will address each of these in turn.

Capacity. Our capacity to be godlike impacts our view of ourselves and of what should characterize our lives as we seek to deepen our relationship with God. While an ethical system that is above reproach should typify Christians, it cannot represent the sum total of the faith. In the end, our Christianity cannot be defined by a set of rules that we live by. Nor can we punch in and punch out by the clock. Our aspiration is to be godlike, and in that goal we find our purpose.

We live in a goal-oriented society that attempts to delineate everything, reducing it to a list so that we can assess the achievement of our goals. Employees are anxious to know precisely by what criteria their job performance will be evaluated. Education is encumbered with outcome assessments and the setting and meeting of measurable objectives. Students want to know what they will be tested on so they can target particular skills or knowledge. College applicants know that the attractiveness to the institution of their choice is going to be encapsulated in their performance on standardized tests. Teachers know that principals are going evaluate them on the basis of the scores of their students, so they teach with an eye toward those tests. Principals know their school is going to be judged by the state on the basis of the scores of the students, so they pressure the teachers. This is the reductionism that drives every aspect of our society, and it has become part and parcel of our Christianity. The good news is that we are free from the law and its potential for reductionism.

When educators talk about measurable outcomes, I get a knot in my stomach, for I firmly believe that there are many important outcomes that cannot be measured. But if they cannot be measured, they get left off the list of targeted outcomes. Just as being educated means more than acquiring certain skills and knowledge, being Christian means more than living according to a set of rules. God tells his people Israel, “Be holy because I, the LORD your God, am holy” (Lev. 19:2). Paul encourages the Philippians, “Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus” (Phil. 2:5), and admonishes the Ephesians “to be made new in the attitude of your minds; and to put on the new self, created to be like God in true righteousness and holiness” (Eph. 4:23–24) and to be “imitators of God” (5:1).

The laws of Israel gave them illustrations of what their faith should look like, but their faith was not circumscribed by the law. Lists like the Beatitudes (Matt. 5:3–12) and the fruit of the Spirit (Gal. 5:22–23) illustrate some of the outcomes of our faith, but no list is comprehensive. We aspire to attain the godlikeness that the image of God has made possible in us.

Dignity. Human dignity impacts how we treat other people. Since all people are in the image of God, all deserve to be treated with the dignity the image affords. This belief will affect our view of how society responds to human needs: those who are sick, imprisoned, bereaved, poverty-stricken, or defenseless. As Christians we can and should seek to shape the society around us in ways that will preserve human dignity, but that will not always be possible in Western society. It is sometimes difficult to identify the path that upholds human dignity in a society that values rights above all else and formulates everything in those terms. We have the right to life, the right to choose, the right to be employed regardless of race or color, the right to equal treatment and equal pay for equal work—the list goes on and on.

How can dignity be preserved in the stampede of rights? When rights are granted (grudgingly?) on theory or coerced through demands, dignity is lost from the equation. If we truly believe in the dignity of all, rights and their protection follow automatically. The protection of rights is inevitable if preservation of dignity is valued. But it doesn’t work the other way; preservation of dignity is not an inevitable result of protection of rights. If minority ethnic groups are treated with dignity, they will not have to wonder whether they have been given the job only because of rights issues. If women are treated with dignity in the workplace, they will not suffer degrading harassment. If we value the dignity of every human, extending to the unborn child, we will have little defense for rights of sexual freedom or rights to choose the child’s death.

We live in a world of rights that has no sense of purpose; we live in a world of tolerance that has no sense of dignity for those tolerated or conscience concerning what is to be tolerated; we live in a world of leisure and squander it on empty pursuit; we live in a world of comfort and convenience where we can accumulate anything we want except that which matters most. Chesterton has summarized this indiscriminate substitution of the cheap for the substantial with typical aplomb and wit:

We are familiar with the argument that comforts that were rare among our forefathers are now multiplied in factories and handed out wholesale to villas and flats; and indeed, that nobody nowadays, so long as he is content to go without air, space, quiet, decency and good manners, need be without anything whatever that he wants; or at least a reasonably cheap imitation of it.33

Thus, dignity has been displaced by cheap imitations in masquerade. But the quest for humane attitudes and actions that go beyond legal rights must engulf the church. Our church sums this up in its mission statement: “To love God and the people He has created.” Even if we cannot achieve it in our society, in our lives we must value dignity higher than rights.

Responsibility. The responsibility aspect of the image of God impacts how we function in the world. This is entwined with the verbs “subdue” and “rule” and leads naturally into a discussion of a Christian view of ecology.

Environmentalism. “The world is becoming dirty and ugly, and it’s time to do something about it. The air is being turned into smog. The rivers are polluted. Toxic chemicals fill the soil. The oceans have become garbage dumps, and trash is piling up on the edges of our cities. . . . Oil spills pollute our beaches, and chemical rain and expanding industry destroy our rain forests.”34 This summary is by Tony Campolo, but similar statements can be found in any book that addresses the problems of the environment.

When such books get around to fixing blame for the mess that we are in, one of the most common targets is the utilitarian rationalism (a result of the Enlightenment) that views the natural world as sitting there just waiting to be used/abused in whatever way will serve humanity (or me, at least). A second target is Christian thinking that either follows Calvin’s conviction that all of nature was put here for human use or believes the end of the world is imminent, so there is no use thinking long-term about the environment. Others blame the Bible itself as the cause of our problems, citing Genesis 1 as the culprit.

We need go no further than the end of the opening chapter of the Bible to find the statement that is often taken to lie at the root of human arrogance and indifference towards the world of nature and which has led many people to see Christianity as being responsible for our current environmental crisis. The message of this well-known verse seems to be clear. Man is lord of all he surveys, given by God the right to do what he likes with the rest of creation which is there simply to satisfy his wants and to be used for his enjoyment.35

It is true that most attempts to construct a theology of the environment base their attempts on Genesis 1:26–28. But what can legitimately be said about environmentalism on this basis? R. Chisholm evaluates the impact of the Hebrew word’s meaning (kbš) on environmentalism by offering a paraphrase of the verse and arriving at a moderate conclusion.

“Have a lot of children and populate the earth! Harness its potential and use its resources for your benefit.” As one can see, the verb does not mean “ruin” or “destroy,” nor does it suggest anything approaching “worship, treat like fragile china, be at one with.” The context of rulership militates against abuse of the earth being in view, but it also prohibits putting the earth on a par with humankind, God’s designated king over the created order. The point seems to be that the earth is at humankind’s disposal.36

Thomas Derr summarizes the typical view of Christian theism that appears to be represented in Chisholm’s conclusions:

[It] places human beings at the apex of nature by design of the ultimate giver of life. Made, as we say, in the image of God, we give ourselves license to claim that our interests as a species take precedence over those of the rest of creation; stewardship of the creation means mainly that we should manage it so that it sustains us indefinitely. Nature is made for us as we are made for God.37

There are valid observations here, but the approach suggested in this commentary offers a different perspective. It is more in keeping with the text to move away from a human-centered view of the cosmos. God has created the cosmos for himself, not for us, though it is true that he has given us high status and privilege in this world of his. Thus, our role in subduing and ruling must be seen as a function of stewardship, not of ownership.38 This world is not ours to dispose of as we will, but it has been put under our charge to manage for its owner, God. That management is not with our own benefit in mind, but with the mindset that this is God’s world.

Often when our family goes away for vacation, we will arrange for students to live in our house. They take care of the dog and watch the house; we give them freedom to go anywhere in the house and use the food in the refrigerator; and we ask them to take in the mail, keep an eye on the place, and so on. It is still our house, but we give them charge of it and allow them to make use of its benefits. If we get home and find that they have let all the food in the refrigerator rot rather than use it, we are disappointed at the waste. But imagine the disappointment we would feel if we found the house wrecked, our things broken, and our dog dead.

Those who claim the support of the Bible for their self-indulgent rape of the environment are no different than the Crusaders, Inquisitioners, Nazis, and White Supremacists who exploit the Bible in order to justify their own, antibiblical agendas. The stewardship model leads us to think of people more as priests in the cosmos rather than as kings over it. This is supported by the language of Genesis 2:15 (see comments there). For now it allows us to think in terms of discharging a responsibility as we live in God’s world. Though I do not share Campolo’s sacramental view of nature, I agree with him as he tries to move the focus of the cosmos off of people.

I increasingly believe that it is a humanistic distortion to think that nature was created by God solely for the benefit of Adam and Eve and their successors. The idea that nature is there simply to provide blessings and gratification for humans seems to me to be more of a manifestation of anthropocentric exaggeration than an expression of how things really are.39

The stewardship model of environmentalism is not a new one and is much to be preferred over biocentrism as a reaction against anthropocentrism. The biblical view rejects biocentrism, which claims that all inhabitants in the cosmos are of equal status (plants, animals, people). People are given a higher status and worth, though the value of plants and animals (bestowed by God) cannot be neglected. Christian biocentrists are more inclined to speak of all of nature being valued by God and loved by God,40 but the type of value God places on nature is not transparent in the text. The text does not give nature “rights,” but it does burden people with responsibility.41 Even our stewardship, however, cannot be for our own sake or our own gain, nor for the sake of the rest of creation, but for the sake of God, the Creator and Possessor of all the earth. This is a theocentric view that shows a respect for what belongs to God.

The ecological crisis is not a consequence of “kabashing” [Nash’s English adoption of the Hebrew root] per se. Survivors in the biophysical world have no choice but to do that. Instead, the ecological crisis is a result of imperialistic overextension—abusing what is divinely intended for use, subduing far beyond the point of necessity, imaging despotism rather than dominion, and failing to nurture benevolently and justly nature’s potential hospitality. It is sin. Whatever tendencies are inherent in the word “subduing” for overreaching human bounds are checked and balanced by the biblical concepts of image and dominion themselves, and by other moral constrictions in scripture and subsequent Christian history.42

But how far do the implications of this respect go? Does Genesis 1 help us answer conflict-of-species questions that occur more and more frequently? As I write, for example, a story from southern California is making the news. Millions of dollars worth of construction in a particular dunes area is being delayed and millions of dollars of bonds are ready to go into default because a certain species of fly that is on the endangered animals list uses that place for its mating grounds. Here it is not human health or welfare at stake, but grandiose building projects, perhaps capable of being brought under the umbrella of subduing but bearing principally economic value. On the other side, it is not the creature’s existence necessarily that is threatened, only its mating grounds.

Additionally, most would agree that flies do not have quite the same ability to generate popular support as pandas or tigers might (though biocentrists would bristle at such politically incorrect species bigotry). I do not believe that this is one the Bible can settle. The values that are at stake (economic well-being and preservation of insect mating grounds) are not easily identifiable biblical values, though I daresay God has an opinion.

The affirmations of Genesis 1, however, are not intended to provide guidance for a detailed position paper and agenda on the environment. God’s revelation to us is designed to help us know him, not to answer all of our questions. We should not expect to be able to extrapolate a comprehensive policy on the environment from proof texts. When faced with complicated issues, we must try to discern what constitutes godly behavior. In the end, it is what kind of people we are that will make the difference and will lead through complicated mazes so that we do the right thing. Campolo’s conclusion hits the issue squarely:

Too often, when I read the books or listen to speeches of environmentalists who are not Christians, I recognize a basic shortcoming. Too frequently, they build their pleas for temperance and self-control on enlightened self-interest. Adopting a more environmentally responsible life-style, they point out, is the only reasonable thing to do if we know what is good for us. But much more than that is needed. We, ourselves, have to become completely different people.43

Family planning. What does Genesis have to say to our overpopulated world? The blessing gave us the privilege of filling the world. Oh that we could succeed in our spiritual privileges as well as we have succeeded in this. Though the blessing did not put limitations on the extent to which the earth could be populated, there are limitations in the size of population that the earth can sustain.

As late as the early seventeenth century, the world population was less than 500 million (less than twice the current population of the United States). In the next three centuries it had doubled twice to more than two billion, and by 1950 it had increased to two and one-half billion. After World War II the population rate skyrocketed, so that the world took not a century but only forty years to double to 5 billion. It is projected to increase by more than another billion by the year 2000, eventually to reach 8.6 billion by 2025.44

It was commonplace in the 1970s to hear and read alarmist reports about population growth and the dangers that were posed when the current growth figures were projected into the next millennium. In the two decades since then, growth rates have slowed considerably, and the dangers are no longer shouted from the street corners. These slower growth rates have been primarily the result of birth control, both voluntary and mandated. If the blessing of Genesis 1 is understood as a privilege rather than an obligation, those countries that regulate the number of children a couple may have cannot be accused of countermanding biblical dictates. Likewise, those couples who choose not to have children (either out of concern for world population or as a result of their lifestyle choices) are not in violation of this Scripture.

What the church needs to be willing to stand against are the means by which population growth is controlled. Population control cannot be used as a euphemism for population reduction. Genocide of the old, the infirmed, the vulnerable, the children (born or unborn), those of other races or nationalities, or at any other level represents denial of the image of God in those being eliminated.

Subduing: functions instead of structures. The environmentalism discussion above was focused toward the whole question of harnessing (or exploiting) our world’s resources, particularly those that are depletable, and the stewardship that is required of us. But if the Genesis account is more about functions than things, perhaps we ought to think about subduing or controlling those functions. For example, we attempt to control time by making more of it. In one sense this has been achieved by stretching the typical life expectancy. Medical research has enabled us to eliminate many of the diseases that threaten to cut time short as well as to improve overall health so that the body lasts longer.

More significant, however, we seek to make more time by reducing the length of time required to do necessary tasks. Again, technology has led the way by introducing many modern conveniences that allow once time-consuming tasks to be undertaken in far less time. Today we use appliances such as washers and dryers, breadmakers, microwave ovens, and food processors. Travel time has been greatly reduced by means of cars, trains, and airplanes. Certainly most influential in recent decades is the impact of the computer. While it is capable of saving much time, it has been observed that it also has badly distorted our view of time. Chicago columnist Bob Greene laments that “time—which our culture keeps trying to save—has, paradoxically, become a meaningless notion. We’ve saved so much of it that it has no true definition.”45 Do you catch yourself on the computer trying to figure out how to do a step with one click instead of two? How many of us have invested serious money to upgrade a computer so that it will perform operations in one second instead of three?

Most important in this issue is the question: Who are we saving time for? We like to think that saving time on mundane chores will give us more time for the “important things of life.” But usually it only increases our leisure time. Perhaps similar to Tevya in Fiddler on the Roof, we fantasize about what we would do if we only had more time. Tevya fantasized about having plenty of money, and he sings: “If I were rich, I’d have the time that I lack, to sit in the synagogue and pray.” That sounds like a good intention, but in the next line he expresses a little self-concern as he imagines himself with a seat by the Eastern Wall, discussing the holy books with the learned “seven hours every day, and that would be the greatest thing of all.”

In a similar way we might also sigh and say to ourselves, “If I only had more time, I could focus more on my spiritual life.” We know that time is valuable, so we seek to control it, redeem it, and save it. In these ways time can be subdued, but we must always remember that time has been given into our hands, ultimately, so that we can give it back to God.