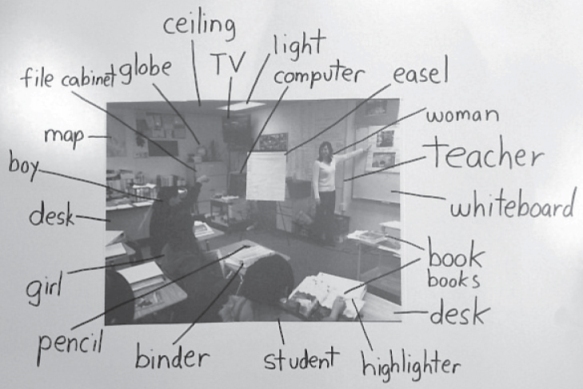

Figure 3.1 Example of Photo Used in the Picture Word Inductive Model

Chapter 3

Key Elements of a Curriculum for Beginning ELLs

A traveling wise man and his friends passed through a town and asked to speak to a local scholar. He was brought to Nasreddin Hodja. The traveler didn't speak Turkish, and Hodja didn't speak any other languages, so they decided to communicate through signs.

The traveler used a stick to draw a large circle in the dirt. Hodja then divided the circle in two with his stick. The traveler followed by drawing a perpendicular line that divided the circle into four quarters and then pointed at the first three quarters and then lastly pointed to the fourth quarter. Hodja then swirled the stick on all four quarters. The traveler used his hands to make a bowl shape with his hands up and wiggled his fingers. Hodja then made a bowl shape with his hands down and wiggled his fingers.

When the meeting was over, the traveler's friends asked him what they had discussed. “Hodja is very intelligent,” he said. “I showed him that the earth was round, and he said that there was an equator in the middle of it. I told him that three-quarters of the earth was water and one quarter of it was land. He said that there were undercurrents and winds. I told him that the waters warm up, vaporize, and move toward the sky. He said that they cool off and come down as rain.” The townspeople surrounded Hodja and asked him the same thing.

“This stranger is hungry,” Hodja started to explain. “He said that he hoped to have a large tray of baklava. I said that he could only have half of it. He said that the syrup should be made with three parts sugar and one part honey. I agreed, and said that they had to mix well. He then suggested that we should cook it on a blazing fire. I suggested that we should pour crushed nuts on top of it.”1

Nasreddin Hodja was a Middle Eastern storyteller who lived in the thirteenth century. In this tale, we see both participants entirely focused on what they want to communicate, and absolutely convinced that they are communicating effectively. These assumptions lead to completely different understandings.

Perhaps we educators should be more concerned with what students hear and learn, and less focused on what we believe we are teaching. It could also be framed as the difference between being effective and being “right.” The more we view learning as a process of guided self-discovery and less one of a “sage on stage”—more of a two-way conversation instead of a one-way communication—the better teachers we might be for our students. The activities described in our book use this perspective as a guide.

Each instructional strategy and lesson in Parts Two and Three indicate where it fits into the six standards domains the state of California mandates for its English language development (ELD, also known as ESL) classes. Similar standards exist in most other states. To make these standards more easily understandable, a one-sentence description developed for each domain by the Sacramento City Unified School District will be used, and its appropriate numbers will be cited throughout this chapter. The full one-sentence summary of each domain can be found in Exhibit 3.1.

Source: “Course of Study for English Language Development,” Sacramento City Unified School District, 2005, pp. 7–12.

In this section we present key learning and teaching activities that we regularly use in a beginning ESL classroom. Though they are divided into two sections for organization purposes—“Reading and Writing” and “Speaking and Listening”—you will find that many of the activities incorporate all four of these language domains.

The Picture Word Inductive Model (PWIM) uses an inductive process (in which students seek patterns and use them to identify their broader meanings and significance), as opposed to a deductive process (where meanings or rules are given, and students have to then apply them). In the PWIM, an enlarged photo with white space around it (ideally laminated so it can be used again) is first placed in the classroom (see Figure 3.1); students and the teacher together label objects in the picture; students categorize and add words to their categories; students use the words in sentences that are provided as clozes (fill-in-the-blank exercises; see Exhibit 3.2), which are then categorized and combined into paragraphs; and, finally, a title is chosen.

Figure 3.1 Example of Photo Used in the Picture Word Inductive Model

The PWIM process can easily be used as the centerpiece for many classroom activities during the year. Each week, a different photo can be connected to an appropriate theme (food, sports, house, and so on), and the instructional process can be made increasingly sophisticated and challenging for students—for example, later the cloze sentences can have two blanks in each and not have words written below them for students to choose. The pictures themselves can be personalized. Local images and ones featuring students could be used. For example, in addition to using a house as the central photo for the class, each student can bring a picture of their own house that they can use for supplementary vocabulary instruction. Students can snap the photos with their cell phone for the teacher to print out, or, with advanced planning, an inexpensive disposable camera can be used by the entire class. Photos can also easily be found on the Web. The best pictures to use in this activity contain one scene with many different objects and generally include people. Occasionally, though, there might be exceptions to these criteria, which are highlighted in the “Year-Long Schedule” section in Chapter Four.

Of course, some themes will take more than one week and/or will require more than one picture. A unit on food, for example, could include separate subunits on healthy eating, eating at a restaurant, shopping at a store, farm life (both as a grower and as a laborer), fruit, vegetables, meat, and dairy.

A Picture Word Inductive Unit Plan describing in detail how to apply the PWIM can be found in Chapter Four. The “Sample Week Schedule” in Chapter Four demonstrates how the PWIM might fit in with other class activities.

Using the PWIM correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. The PWIM is a literacy instructional strategy that was designed for early literacy instruction and has also been found to be exceptionally effective with both younger and older second-language learners.2 It was developed by Emily Calhoun,3 and some studies have found its use resulting in literacy gains of twice the average student, and as great as eight times the average gain for previously low-performing students.4 It takes advantage of student prior knowledge and visual clues and builds on the key strength of inductive learning—the brain's natural desire to seek out and remember patterns.5

A recent study also reinforced the importance of having students repeat aloud new vocabulary, as is done using the PWIM. Researchers found that saying the word aloud helped learners develop an “encoding record” of the new word.6

Text Data Sets are very similar to the PWIM cloze sentences, and students use the same kind of categorization process done in that activity. Text Data Sets, however, are composed of sentences or short paragraphs. See Exhibit 3.3 for a Text Data Set that is appropriate for beginners. See Chapters Six and Eight for examples of more advanced Text Data Sets. Students first classify them (individually or with partners), being sure to highlight or underline their evidence for determining that the example belonged in that specific category. They might use categories given to them by the teacher or ones they determine themselves. Then they might add new pieces of data they find and/or they may convert their categories into paragraphs and a simple essay. They might also just stop at the categorization process. These data sets are another scaffolding tool in the inductive teaching and learning process that can be used by students to develop increasingly sophisticated writing skills.

Photos on the Web

Using Text Data Sets correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6.

Critical pedagogy is the term often used to describe a teaching approach whose most well-known practitioner was Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Freire was critical of the “banking” approach towards education, where the teacher “deposits” information into her students. Instead, he wanted to help students learn by questioning and looking at real-world problems that they, their families, and their communities faced. Through this kind of dialogue, he felt that both students and the teacher could learn together.7 Freire was careful to call his learning approach a “problem-posing” one, not a “problem-solving” exercise. He wanted to put the emphasis on teachers raising questions through this process and not giving solutions.8

There are many ways to use this strategy in the ESL classroom. One way is to first show a very short video clip, photo, cartoon, newspaper article, song, or comic strip or, if the English level of the class is advanced enough, students can act out a dialogue that represents a common problem faced by students (a teacher can also perform the dialogue on his own). Ideally, it should be connected to the thematic unit that is being studied at that time, and should reflect an actual problem students or their families have faced or are facing. However, there is no need to be strictly limited to the thematic unit, and issues may arise in students' lives at any time that can provide learning opportunities. The problems can be identified by the teacher first modeling an example and then by eliciting ideas of problems from students. Students can also draw their own representations of the problems.

For example, if the thematic unit is school, a short video clip from the movie My Bodyguard can be shown to illustrate the problem of bullying. Students can then work in pairs and small groups in a five-step process responding to the following questions,9 with a class discussion after each one (certain words may need to be simplified and/or defined, especially when done for the first time):

Students can create simple posters and make presentations (including role-plays) illustrating the problem, sharing their personal connection to it, listing potential solutions, and choosing which one they think is best and why. As students become more advanced, they can develop this outline into a problem-solution essay using the same outline (see Chapter Six for more ideas on how to support students writing a problem-solution essay). Students can also take real-world actions to confront the problem, as one of our classes did by organizing a fair bringing ten different job training agencies to our school so they and their families could learn what services were available (see Chapter Six for more information on action projects).

This five-step outline can be used to approach multiple problems on a weekly or biweekly schedule for different thematic units—perhaps discussing the problem of unemployment when learning about jobs, not having health insurance when discussing a medical unit, or landlord issues during a week on home. Each time the problem can be demonstrated in a different form, and each time students can be challenged to present their answers in an increasingly more sophisticated way.

As ELLs increase their language proficiency, an extra step can be inserted into the five-point outline to incorporate another level of inductive learning: it can be numbered 2.5 or later in the process. Students can be asked to make a list of questions they would need answered about the problem in order to solve it (during the first time using this strategy, teacher modeling might be necessary). For example, questions about the bullying video could include:

Students can then be asked to categorize the questions into the broad areas needed to solve most problems—researching information, identifying allies, and preparing for a reaction. They can then use similar questions and categories to develop their own specific action plan to solve the more personal problems they identify and present those plans with their solutions. Finally, students can perform short role-plays or draw a comic strip portraying how they would solve the problems.

Using the critical pedagogy correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. Using the kind of problem-based learning exemplified in these kind of critical pedagogy lessons has brought many benefits to the ESL classroom. These include the more authentic issues represented in the process promoting enhanced language acquisition, compared to prepackaged dialogues and worksheets or role-plays. In addition, it has been found to increase the likelihood of learners applying the classroom content to their outside lives.10

Digital Storytelling

Free Voluntary Reading, also called Extensive Reading, Silent Sustained Reading, and recreational reading, is the instructional strategy of letting students choose books or other reading material they want to read with minimal or no academic work connected to it. Its purpose is to promote the enjoyment of reading. It's expected that since students are choosing the books they will read, they will also feel more motivated to want to learn the new vocabulary that appears in them. Students are also encouraged to change books if they find the one they are reading to be uninteresting.

Though students are typically not assessed on what they are reading, students can be encouraged to interact with the text through the use of reading strategies. Without this kind of encouragement, students can more easily fall into the trap of learning to “decode” words without truly understanding their meaning. Teachers can model what good readers do through short and simple “think-alouds” (see Exhibit 3.4). Teacher comments are noted in the exhibit. (Read-alouds, where short passages are read to students without modeling reading strategies, are also an effective instructional method. See Chapters Five and Six for further information.)

A teacher can identify short, accessible passages and over a period of a few weeks use this sequence with students:

Students can be given a simple form (see Exhibit 3.5) that asks them to show a few reading strategies each week. It is less important that students are using all the reading strategies correctly. It is more critical for them to recognize that genuinely understanding any text requires readers to be proactive and not passive.

Name __________

Period __________

Date __________

Reading Log

or

or

| Date | Book or Story Title | Reading Strategy Used |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Students can begin each class with fifteen minutes of silent reading (part of that time can also be spent with partners reading the same book together if they choose). An important consideration is what the teacher is doing during this period of time. Though some suggest that the teacher should also be a model and read during the same time, we feel strongly that it is more important to be walking around, asking students questions, having them read aloud short passages, and so forth. Not only does this kind of interaction serve as a good formative assessment, but at least one important study has also found it to be a good instructional strategy. In an article in the Journal of Educational Psychology, researchers found that teachers providing individual feedback to students during this kind of reading time was by far one of the most effective ways to help improve students' reading ability. It primarily looked at students using their silent reading time to read class text (though not exclusively), but it seems close enough to the basic ideas of Free Voluntary Reading that we should carefully consider what they found.11 Reading at home for twenty minutes each night could also be homework.

In addition, students can be encouraged to talk with their classmates using simple Book Talks, which are explained more in Chapter Five and in Exhibit 5.4.

Using Free Voluntary Reading and reading strategies correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. Numerous studies have shown the benefits of Free Voluntary Reading, particularly with English language learners.12 A review of twenty-three studies showed that in all cases ELLs using Free Voluntary Reading had a higher gain in reading comprehension than those in classes not using the strategy. In addition, other research has demonstrated that ELLs using Free Voluntary Reading have greater gains in writing, grammar usage, and spelling.13

Research by Professor Jim Cummins also supports explicit teaching and learning of reading comprehension strategies.14

Online Books

These three dictation exercises combine reading and writing skills with developing listening and speaking skills.

Interactive Dictation. In interactive dictation, students are assigned a simple passage or a book the class has been using, so students are familiar with it. They are then divided into pairs or triads, and each student is given a small whiteboard, marker, and eraser (or blank sheets of paper). One student reads a few words while the other(s) write them down. The writers can look at their copy of the text as a kind of cheat sheet, but should be encouraged to work toward not using it. The reader can give feedback on the accuracy and errors of the writer.

Dictogloss. Dictogloss can be done a number of different ways but here is one variation. First, students divide their papers in half. Then the teacher reads a short text, often one students are familiar with. After the first time of just listening, the teacher reads it again and students write down notes on one-half of the paper about what they have heard. Next the teacher reads it a third time and again the students write down additional notes in the same space. Students then compare their notes with a partner and they work together to develop a reconstruction of the text—one that is not the exact wording, but that demonstrates its meaning accurately. Finally, the teacher reads the selection again and students judge how well they did.

Picture Dictation. In picture dictation, the teacher can draw or find a simple image and, without showing it to the class, describe it while students draw. It can also be a partner activity where half of the class is given one picture and the other half a different one. Students with different pictures are made partners and stand up a book or folder between them. One student describes her picture while the other draws. When it's complete and the student is given feedback, the roles can be reversed. Students can also be asked to write sentences describing the picture.

Picture dictation is one of many exercises (and our favorite one) that fall under the broad category of “information gap” activities. They are generally designed as partner exercises where one student has to get information from the other—speaking the target language—in order to complete the assignment.

Using Communicative Dictation Activities correlates with California ELD domains 1 and 6.

Supporting Research. Numerous studies have shown that communicative dictation activities can increase student engagement,15 enhance English listening comprehension,16 and improve grammar skills.17 These communicative activities are different from the often deadly teacher-centered uses (passages repeated multiple times in a “drill-and-kill” fashion until students get it “right”), which can be particularly frustrating for beginning-level learners.

Online Dictation Exercises

Concept attainment, originally developed by Jerome Bruner and his colleagues,18 is a form of inductive learning where the teacher identifies both “good” and “bad” examples (ideally, taken from student work—with the names removed, of course) of the intended learning objective. After developing a sheet like the one in Exhibit 3.6, which is designed to practice conjugating the verb “to be” correctly, the teacher would place it on a document camera or overhead projector. At first, everything would be covered except for the “Yes” and “No” titles, and the teacher would explain that he is going to give various examples and he wants students to identify why certain ones are under “Yes” and others are under “No.”

| Yes | No |

| Hmong food is good. | |

| Many people is big and heavy. | |

| The food is spicy. | |

| Hmong foods is good. | |

| It is a sort of soup that Hmong people eat. | |

| Ginger and galangal is good | |

| The foods are spicy. | |

| Hmong food are natural. | |

| American foods are not spicy. | |

| Papaya salad are good and spicy. |

After the first “Yes” and “No” examples are shown, students are asked to think about them and share with a partner why they think one is a “Yes” and one is a “No.” After the teacher calls on people, if no one can identify the reason, he continues uncovering one example at a time and continues the think-pair-share process with students until they identify the reasons. Then students are asked to correct the “No” examples and write their own “Yes” ones. Last, students can be asked to generate their own “Yes” examples and share them with a partner or the class. This inductive learning strategy can be used effectively to teach countless lessons, including ones on grammar, spelling, composition, and even speaking (using recorded audio).

We have even used this strategy to teach essay organization by taping parts of essays on the classroom wall under “Yes” and “No”—with names removed and after getting permission to do so from the student authors. This kind of exercise is much easier to do when there are positive relationships throughout the classroom.

Using concept attainment correlates with California ELD domains 1, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. Concept attainment is another instructional strategy that builds on the brain's natural desire to seek out patterns. Judy Willis, neurologist, teacher, and author, writes: “Education is about increasing the patterns that students can use, recognize, and communicate. As the ability to see and work with patterns expands, the executive functions are enhanced. Whenever new material is presented in such a way that students see relationships, they generate greater brain cell activity (forming new neural connections) and achieve more successful long-term memory storage and retrieval.”19

Numerous studies have shown that concept attainment has a positive effect on student achievement, including with second-language learners.20

Concept attainment, like the other forms of inductive teaching and learning discussed in this chapter (Picture Word Inductive Model and Text Data Sets) can also be described as an example of “enhanced discovery learning.” In a recent meta-analysis of hundreds of studies, researchers found that “enhanced discovery learning” was a more effective form of teaching than either “direct instruction” or “unassisted discovery learning.”21

Online Writing Practice

The Language Experience Approach involves the entire class doing an activity and then discussing and writing about it. The activity could be

Immediately following the activity, students are given a short time to write down notes about what they did (very early beginners can draw). Then the teacher calls on students to share what the class did—usually, though not always, in chronological order. The teacher then writes down what is said on a document camera, overhead projector, or easel paper. It is sometimes debated whether the teacher should write down exactly what a student says if there are grammar or word errors or should say it back to the student and write it correctly—without saying the student was wrong. We use the second strategy and feel that as long as students are not being corrected explicitly (“That's not the correct way to say it, Eva, this is”), it is better to model accurate grammar and word usage. Students can then copy down the class-developed description. Since the text comes out of their own experience, it is much more accessible because they already know its meaning.

The text can subsequently be used for different follow-up activities, including as a cloze (removing certain words and leaving a blank which students have to complete); a sentence scramble (taking individual sentences and mixing-up the words for learners to sequence correctly); or mixing-up all the sentences in the text and having students put them back in order.

Using the Language Experience Approach correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. Respected ESL researchers Suzanne Peregoy and Owen Boyle have found that “the language-experience approach is one of the most frequently recommended approaches for beginning second-language readers. The beauty of the approach is that the student provides the text, through the dictation, that serves as the basis for reading instruction. As a result, language-experience reading is tailored to the learner's own interests, social, and cultural strengths and interest the student brings to school.”22

Online Audio Recording

Collaborative story writing can be done in a number of ways and bears some similarities to the Language Experience Approach.

One example is to start by dividing the class into groups of three. Within the small groups, each person is numbered either one, two, or three. Each group is given one sheet of paper, and at the top of each paper the group writes “Once Upon a Time …” (at times, it might make sense to provide some parameters for the story so it is connected to the thematic unit the class is studying—such as food or school—but, as we discussed earlier, it's okay not to have all activities directly connected to the theme at all times).

Next the teacher puts a piece of paper under the document camera and projects it on the screen and writes:

This means that the number ones in each group have to write one sentence describing who was going to be in the story. Students can be encouraged to have fun with it and pushed to write adjectives (“the ugly monster” and the “handsome boy”). Students are given no more than two minutes to write it, and their group members can help.

The teacher then writes:

All the number twos have to take the paper and write where the story was taking place. Students generally began to get engaged in the exercise at this point.

The process continues until the paper on the overhead looks like this:

The entire small group then determines how the story ends.

Students can then be given a big piece of easel paper to convert their sentences into a story with illustrations. Next, in a round-robin fashion, each group can tell and show their story to the other groups.

Follow-up activities with the texts can be similar to the ones suggested in the Language Experience Approach section. In addition, students can even convert their story into a short skit they perform for the class.

Writing collaborative stories correlates with California ELD domains 1, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. Working in small groups has consistently been found to develop second-language learner self-confidence and increase opportunities for language interaction. Specifically, it results in more student speaking practice and reduces future student errors because of those increased practice opportunities, along with students feeling more motivated and engaged in learning.23

Online Collaborative Storytelling

Countless debates have taken place about the amount of time that should be spent on teaching phonics and which instructional method should be used to teach them. Extensive research supports the idea of spending limited time teaching what Stephen Krashen calls “basic phonics,” the very basic consonant and vowel rules needed for students to comprehend text.24 We believe that using an inductive process is the most effective and engaging way to teach these basic phonics.

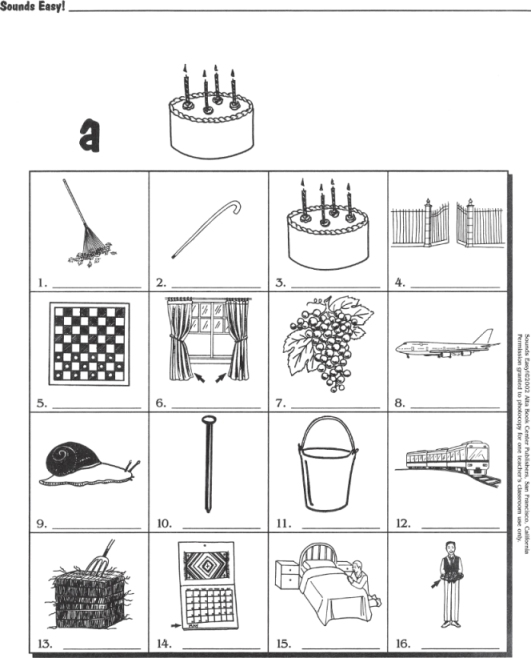

The easiest tool to use in this process is the book Sounds Easy by Sharron Bassano.25 A sample page from the book can be found in Exhibit 3.7. It is designed for use with beginning ELLs from grade five through adult education. The inductive method we recommend builds upon and adds to the instructional strategy suggested in the book.

Source: S. Bassano, Sounds Easy! Phonics, Spelling, and Pronunciation Practice (Provo, UT: Alta Book Center, 2002). Copyright © 2002 Alta Book Center Publishers. Reproduced by permission.

First, copies of a page from the book are distributed to students. In the case of Exhibit 3.7, it is a page with a series of pictures that can be described by words with the long a sound. Each picture has one or more of the letters in the describing word missing. The teacher has the same sheet on the overhead or document camera. The teacher says the number of the picture, gives students a few seconds to complete the blanks with what they believe goes there, and then the teacher writes the correct letters (students correct their papers if they have made any mistakes).

After the sheet is complete it is reviewed again. The teacher can point rapidly to the different pictures and ask for a choral response, doing it faster and faster to make it a more fun activity. Then students work with partners to practice pronouncing the words. Next they work together to put the words into two or three categories. They could be “words that have ai,” “words that have an a with a silent e at the end,” or categories that reflect how they are used—such as food, for example.

Pairs then become groups of four to compare and explain the reasoning behind their categories. The groups then choose which categories they think are best and add words to them using what they learned from the Picture Word Inductive Model activity, dictionaries, or other resources. They can create posters of the categories and share them with the class, along with one, two, or three phonics rules they might have learned.

More often than not, students themselves will identify the key phonics “rules” that apply—in this case, that the letter a would be pronounced with a “long” sound if it was the third letter from the end of a word that ended with an e or if it was the second from the last letter if the last letter was a y. In addition, the letter a would likely be pronounced with a “long” sound if it appeared as an ai.

In reading activities later that day or shortly thereafter, the teacher and students can highlight instances where this rule applies.

Of course, it is not necessary to use this entire inductive process for every letter sound. Teachers should use their judgment about which sounds they think are the most important, how it fits into the other units they are teaching at the time, and the energy level displayed by their students on any given day.26

Teaching phonics inductively correlates with California ELD domains 1 and 2.

Supporting Research. Extensive research demonstrates that an intensive emphasis on explicit phonics instruction can lead students to focus on decoding instead of comprehension. Along with the previously cited studies by Krashen,27 he has done further review of the confirming research (for a list of Krashen's publications see http://sdkrashen.com), as has Professor Brian Cambourne.28

In addition to the support previously cited for inductive teaching and learning, studies have shown students in inductive learning classrooms scoring as much as 30 percent higher in assessments than those using deductive models.29 In addition, ESL researcher H. D. Brown writes that “most of the evidence in communicative second language teaching points to the superiority of an inductive approach to rules and generalizations.”30

Phonics Practice

Total Physical Response

The purpose of Total Physical Response (TPR) is to have students physically act out the words and phrases being taught by the teacher. One way to implement TPR is by first asking all students to stand, and they can move to the front or stay where they are. Two students are brought to the front. The teacher models a verb or two—for example, “sit” and “stand.” She then asks the two students in front to “sit,” “stand,” “sit,” and “stand.” The two students are asked to return to their regular places, and the teacher then tells the class to “sit” and “stand” several times. Students can then divide into partners or in small groups and take turns giving each other commands.

TPR can be an engaging activity by spending ten minutes a day doing it and focusing on a few words each time. Once key verbs are learned, the commands can be made more complicated and even silly. More complicated play-acting scenes can eventually be used (“open the peanut butter jar, put some on your knife, and lick it”). One nice change of pace can be having a student give the commands to the class and creating opportunities where students can give commands to the teacher!

Using Total Physical Response correlates with California ELD domains 1 and 6.

Supporting Research. TPR was originally developed by Dr. James J. Asher and modeled from his analysis of how a child learns—by doing more listening than speaking and by often responding to commands from his parents.31

Numerous studies have documented its effectiveness,32 and TPR is used in ESL and EFL classes around the world.

Online TPR

Songs can be an all-purpose tool in the ESL classroom. Many students who are reluctant to speak feel more comfortable singing with a group. Music is a universal language that most people enjoy. In addition to speaking practice, songs provide multiple opportunities for listening, reading, and even writing practice. Using pop songs can be much more engaging for older students. However, simple songs geared specifically to teaching children or ELL vocabulary can often be useful—and enjoyed by everybody!

Here are just a few ways to use songs in the classroom:

Using music correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2 and 6.

Supporting Research. Extensive research has shown that using songs is an effective language-development strategy with English language learners.33 They are often accessible because popular songs use the vocabulary of an eleven-year-old, the rhythm and beat help students speak in phrases or sentences instead of words, and the word repetition assists retention.34 Neuroscience has also found that music can increase dopamine release in the brain and generates positive emotions. This kind of emotional learning reinforces long-term memory.35

Music Sites for ELLs

Carolyn Graham is well known for developing the concept of Jazz Chants to teach English. These are short, rhythmic chants that reinforce vocabulary and/or grammar lessons in a fun way.

She encourages teachers to create their own chants.36 One of her recommendations is to start with three words—the first one having two syllables, the second three, and the third having one. For example, if your thematic unit is school, a vocabulary chant could be

Having students clap and chant in unison for a minute or two, with the teacher or a student pointing to each item, could be a fun reinforcing activity.

Or, as Graham suggests, the same words could be turned into a grammar chant:

These can be chanted together or in rounds.

Of course, just about anything can be turned into a chant, and chants don't always have to meet these criteria. For example, a chant can be structured in a question-and-response format with students on different sides of the room saying one or the other. Advanced students can also create their own chants and teach them to the class.

Using chants correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2 and 6.

Supporting Research. These kinds of chants have the same advantages cited by research supporting songs in the classroom37 and are particularly helpful for teaching stress and intonation.38 A big benefit to chants is that it is far easier and quicker to compose a chant than a song!

Short dialogues, ideally related to the thematic unit that is being studied and that has practical use outside the classroom, can be a useful tool for oral language practice. After teacher modeling, students—in pairs, threes, or fours—can practice and perform in front of the class or for another small group. It's often helpful to inject some humor into the dialogue.

There are several ways to vary this activity:

Using dialogues correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2 and 6.

First Week of School Dialogue

Supporting Research. Dialogues have been found to be effective forms for language practice and confidence building. Students who have practiced within the relatively nonthreatening environment of the classroom will be more likely to actually use the language outside of school.39

Online Dialogues

This is a modification of an exercise developed by Paul Nation called the 4–3–2 Fluency Activity.40 In his original activity plan, students line up (standing or sitting) facing each other. Each one must be prepared to speak on something that they are already quite familiar with. First, they speak to their partner for four minutes about the topic. Then they move down the line and say the same thing for three minutes to a new partner. Next they move again and speak for two minutes. Then the students on the other side do the same thing.

We developed a modification of this activity that could be called 3–2–1 or, for beginners, even 2–1.5–1. In it, students are told to pick any topic they know a lot about, and they will be asked to talk about it to a partner for three minutes (or two minutes, depending on the English level of the students), and then for two minutes and then for one. But first, they should write down notes about what they might want to say.

Next, if possible, students are taken to a computer lab where they practice speaking by recording all or part of what they want to say. Afterward, students are told they have two minutes to review their notes before they have to be put away. Next the teacher models questions that students who are listening can ask the speaker if they appear to be stuck. It is also useful to model characteristics of being a good listener (such as maintaining eye contact and not talking to other students). Then students begin the speaking and switching process described earlier. Later, if feasible, students can go back to the computer lab and record their speaking again so they can compare and identify improvement.

Using the 3–2–1 activity correlates with California ELD domains 1, 2 and 6.

Supporting Research. Regular use of the 4–3–2 exercise has been shown to improve learners' fluency, producing natural and faster-flowing speech.41

We've already described one way of using videos with the Language Experience Approach. Another technique called Back to the Screen is adapted from Zero Prep: Ready-to-Go Activities for the Language Classroom by Laurel Pollard, Natalie Hess, and Jan Herron.42 The teacher picks a short clip from a movie (the famous highway chase scene from one of the Matrix movies, for example) and then divides the class into pairs, with one group facing the TV and the other with their backs to it. Then, after turning off the sound, the teacher begins playing the movie. The person who can see the screen tells the other person what is happening. Then, after a few minutes, the students reverse places. Afterward, the pairs write a chronological sequence of what happened, which is shared with another group and discussed in class. Finally, everyone watches the clip, with sound, together.

Another way to use videos is to have students watch short clips and create questions about what they saw and heard. The questions can then be exchanged with a classmate to answer. An example of this strategy can be found in Chapter Five and in Exhibit 5.10.

It's important to show subtitles when using videos in an ESL class. Showing English subtitles during English videos improves listening and reading comprehension among English language learners.43

Using video in the described ways correlates with California ELD domains 1, 5 and 6.

Supporting Research. Substantial evidence suggests that the visual clues offered by video have a positive effect on student listening comprehension.44 In addition, video use has been shown to have a positive impact on student motivation to learn.45

Online Videos

Improvisation is an activity done without student preparation. Here is one way to incorporate it into the classroom.

Each student can be given a small whiteboard—these are versatile and inexpensive, and if you don't want to buy them you can make them easily, too—along with a marker and cloth eraser. The teacher can explain (the first time—after that, students will understand what to do) that he will start off a conversation and that students will write on their board what they might say in response and hold it up so everyone can see it. The teacher then chooses one of the responses they wrote, and, in turn, responds to it, and so on.

Here is what happened in one of our classrooms when we first tried this activity:

I began by saying that I was holding onto a cliff with my fingers and ready to fall. I then yelled “Help!” and told students to write a response on their whiteboards. Students immediately got the idea and the fun began. Responses included “No” “Why should I?” “What do you need?” and “Goodbye.” Some students just held up their boards and I asked others to share their responses aloud. I chose “Why should I?” to respond to and said “I'm going to die if you don't help, please!” The next responses, with much laughter, included “I will step on your fingers to help you fall!” “What will you pay me?” and “Have a good trip.” In print, it may sound like I have a class of crazed students, but it was all done in fun, and everybody participated. I would also point at various people for them to say what they wrote, too.

I next asked them to imagine that I was a pretty girl or a handsome boy, and said, “Will you go on a date with me?” A similar process then began, including at one point my asking, “What restaurant will you take me to?” followed by “I don't want to go there.” Many students came back with responses like “Too bad,” but one wrote “Where do you want to go?” I pointed out that the student who came up with that response was likely to get far more dates than the rest of them.

Lastly, I said “You are getting an F in this class and will have to repeat it again next year.” Needless to say, an energetic conversation followed.46

Very simple scenarios can be chosen that relate to the thematic unit being studied, and students can begin taking turns up front, developing a scenario, choosing which responses they want to pick, and responding to them.

Using improvisation correlates with California ELD domains 1 and 6.

Supporting Research. Improvisation in music has been shown to deactivate parts of the brain that provide “conscious control, enabling freer, more spontaneous thoughts and actions,” according to scientists.47 These same researchers have discovered connections between music and language, suggesting that improvisation can lead to greater fluency in language, as well as music.

1 L. Eskicioglu, “Scientific Meeting,” 2001. Retrieved from http://www.readliterature.com/h010429.htm.

2 B. Joyce, M. Hrycauk, and E. Calhoun, “A Second Chance for Struggling Readers.” Educational Leadership 58, no. 6 (Mar. 2001); K. D. Wood and J. Tinajero, “Using Pictures to Teach Content to Second Language Learners.” Middle School Journal 33, no. 5 (2002): 47–51. Retrieved from http://www.amle.org/Publications/MiddleSchoolJournal/Articles/May2002/Article7/tabid/423/Default.aspx.

3 E. Calhoun, Teaching Beginning Reading and Writing with the Picture Word Inductive Mode (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1999).

4 E. Calhoun, T. Poirier, N. Simon, and L. Mueller, Teacher (and District) Research: Three Inquiries into the Picture Word Inductive Model. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle, WA, April 2001. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED456107.pdf.

5 D. Wilson and M. Conyers, 60 Strategies for Increasing Student Learning (Orlando, FL: BrainSmart, 2011).

6 J. D. Ozubko and C. M. Macleod, “The Production Effect in Memory: Evidence That Distinctiveness Underlies the Benefit.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 36, no. 6 (2010): 1543–49. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20804284.

7 M. K. Kabilan, “Developing the Critical ESL Learner: The Freire's Way.” ELT Newsletter, June 2000. Retrieved from http://www.eltnewsletter.com/back/June2000/art192000.shtml.

8 I. Shor, Freire for the Classroom (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1987), 164.

9 L. Ferlazzo, “Freire's Learning Sequence.” Library Media Connection, Jan./Feb. 2011. Retrieved from http://linworth.com/pdf/lmc/hot_stuff/LMC_JanFeb11_MediaMaven.pdf, 5

10 J. Mathews-Aydinli, Problem-Based Learning and Adult English Language Learners. CAELA Brief (Washington, DC: Center for Adult English Language Acquisition, Apr. 2007). Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/caela/esl_resources/briefs/Problem-based.pdf.

11 C. C. Block, S. R. Parris, K. L. Reed, C. S. Whiteley, and M. D. Cleveland, “Instructional Approaches That Significantly Increase Reading Comprehension.” Journal of Educational Psychology 101, no. 2 (2009): 262–81. Retrieved from http://bestpracticesweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Best-uses-of-independent-reading-time-Article.pdf.

12 L. Ferlazzo, “The Best Resources Documenting the Effectiveness of Free Voluntary Reading,” Feb. 26, 2011. Retrieved from http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org.

13 S. Krashen, 81 Generalizations about Free Voluntary Reading. IATEFL Young Learner and Teenager Special Interest Group Publication, 2009. Retrieved from http://successfulenglish.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/81-Generalizations-about-FVR-2009.pdf.

14 J. Cummins, Computer Assisted Text Scaffolding for Curriculum Access and Language Learning/Acquisition. Retrieved from http://iteachilearn.org/cummins/comptext.html.

15 C. O. Kit, “Report on the Action Research Project on English Dictation in a Local Primary School.” Hong Kong Teachers' Centre Journal 2 (2004): 1–10. Retrieved from http://edb.org.hk/hktc/download/journal/j2/P1–10.pdf.

16 G. R. Kiany and E. Shiramiry, “The Effect of Frequent Dictation on the Listening Comprehension Ability of Elementary EFL Learners.” TESL Canada Journal 20, no. 1 (2002): 57–63.

17 R. Kidd, “Teaching ESL Grammar through Dictation.” TESL Canada Journal 10, no. 1 (1992): 49–61.

18 J. Bruner, J. J. Goodnow, and G. A. Austin, A Study of Thinking (New York: Science Editions, 1967).

19 J. Willis, Research-Based Strategies to Ignite Student Learning (Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2006), 15.

20 N. Shamnad, Effectiveness of Concept Attainment Model on Achievement in Arabic Grammar of Standard IX Students. Unpublished thesis, Mahatma Ghandi University, Kottayam, India, 2005.

21 L. Alfieri, P. J. Brooks, N. J. Aldrich, and H. R. Tenenbaum, “Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning?” [Abstract.] Journal of Educational Psychology 103, no. 1 (2011): 1–18. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/index.cfm?fa=buy.optionToBuy&id=2010–23599–001; R. J. Marzano, “The Perils and Promises of Discovery Learning.” Educational Leadership 69, no. 1 (2011): 86–7. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept11/vol69/num01/The-Perils-and-Promises-of-Discovery-Learning.aspx.

22 S. F. Peregoy and O. Boyle, Reading, Writing, and Learning in ESL (Boston: Pearson Education, 2008), 279.

23 X. Liang, B. A. Mohan, and M. Early, “Issues of Cooperative Learning in ESL Classes: A Literature Review.” TESL Canada Journal 15, no. 2 (1998): 13–23. Retrieved from http://www.teslcanadajournal.ca/index.php/tesl/article/viewFile/698/529; E. K. Polley, Learner Perceptions of Small Group and Pair Work in the ESL Classroom: Implications for Conditions in Second Language Acquisition. Unpublished thesis, University of Texas, Arlington, 2007. Retrieved from http://dspace.uta.edu/bitstream/handle/10106/315/umi-uta-1643.pdf?sequence=1.

24 S. Krashen, “Basic Phonics.” TexTESOL III Newsletter (Nov. 2004): 2–4.

25 S. Bassano, Sounds Easy! Phonics, Spelling, and Pronunciation Practice (Provo, UT: Alta Book Center, 2002). Retrieved from http://altaesl.com/Detail.cfm?CatalogID=1543.

26 L. Ferlazzo, English Language Learners: Teaching Strategies That Work (Santa Barbara, CA: Linworth, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, 2010), 86.

27 Krashen, “Basic Phonics”; S. Krashen, 81 Generalizations about Free Voluntary Reading, IATEFL Young Learner and Teenager Special Interest Group Publication, 2009. Retrieved from http://successfulenglish.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/81-Generalizations-about-FVR-2009.pdf.

28 B. Cambourne, The Drum Opinion (Oct. 13, 2009). Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/29262.html.

29 L. Ferlazzo, English Language Learners: Teaching Strategies That Work, 78.

30 H. D. Brown, Principles of Language Learning and Teaching, 5th ed. (White Plains, NY: Pearson Longman, 2007), 105.

31 A. M. Dettenrieder, Total Physical Response Storytelling and the Teaching of Grammar Rules in Second Language Instruction. Unpublished research project, Regis University, 2006. Retrieved from http://adr.coalliance.org/codr/fez/eserv/codr:559/RUETD00307.pdf.

32 J. J. Asher, The Total Physical Response (TPR): Review of the Evidence, May 2009. Retrieved from http://www.tpr-world.com/review_evidence.pdf.

33 K. Schoepp, “Reasons for Using Songs in the ESL/EFL classroom.” The Internet TESL Journal VII, no. 2 (2001). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Schoepp-Songs.html.

34 X. Li and M. Brand, “Effectiveness of Music on Vocabulary Acquisition, Language Usage, and Meaning for Mainland Chinese ESL Learners.” Contributions to Music Education 36, no. 1 (2009): 73–84. Retrieved from http://krpb.pbworks.com/f/music-esl.pdf.

35 E. Jensen, “Music Tickles the Reward Centers in the Brain.” Brain-Based Jensen Learning, June 1, 2001. Retrieved from http://www.jensenlearning.com/news/music-tickles-the-reward-centers-in-the-brain/brain-based-learning.

36 C. Graham, “How to Create a Jazz Chant.” Teaching Village, May 23, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.teachingvillage.org/2010/05/23/how-to-create-a-jazz-chant-by-carolyn-graham.

37 L. Ferlazzo, “The Best Sites (and Videos) for Learning about Jazz Chants,” July 28, 2011. Retrieved from http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org.

38 F. Tang and D. Loyet, “Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Jazz Chants.” Idiom, Fall 2003. Retrieved from http://www.nystesol.org/pub/idiom_archive/idiom_fall2003.html.

39 S.-Y. Wu, “Effective Activities for Teaching English Idioms to EFL Learners.” The Internet TESL Journal XIV, no. 3 (2008). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Wu-TeachingIdioms.html.

40 L. Ferlazzo, “How We Made an Excellent Speaking Activity Even Better,” Apr. 11, 2011. Retrieved from http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org.

41 P. Nation, “The Four Strands.” Innovation in Language Teaching 1, no. 1 (2007): 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.victoria.ac.nz/lals/staff/Publications/paul-nation/2007-Four-strands.pdf.

42 L. Pollard, N. Hess, and J. Herron, Zero Prep for Beginners: Ready-to-Go Activities for the Language Classroom (Provo, UT: Alta Book Center, 2001).

43 National Center for Technology Innovation and Center for Implementing Technology in Education, “Captioned Media: Literacy Support for Diverse Learners.” Reading Rockets, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.readingrockets.org/article/35793.

44 C. Canning-Wilson, “Practical Aspects of Using Video in the Foreign Language Classroom.” The Internet TESL Journal VI, no. 11 (2000). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Canning-Video.html.

45 Canning-Wilson, “Practical Aspects of Using Video in the Foreign Language Classroom”; R. T. Williams and P. Lutes, Using Video in the ESL Classroom. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.takamatsu-u.ac.jp/library/06_gakunaisyupan/kiyo/no48/001–013_williams.pdf.

46 L. Ferlazzo, “Improvisation in the ESL/EFL Classroom—at Least in Mine,” Dec. 2, 2009. Retrieved from http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org.

47 C. Sherman, The Neuroscience of Improvisation. The Dana Foundation, June 13, 2011. Retrieved from http://dana.org/news/features/detail.aspx?id=33254.