A gust of wind sent a brilliant cluster of red maple leaves spiralling past her as she looked from the balcony onto the main parade. They would be replaced by cherry trees in spring, peonies in early summer, then chrysanthemums before it all started again. Only in Yoshiwara could one street be the perfect place to view every season.

She looked down and saw the usual mix of people as afternoon passed into evening – tourists gawking at the famed quarter, eager to see but lacking the money or desire to taste its fruits; writers and artists emerging from a hard day’s work or a particularly long night; and merchants, dandies and samurai filtering in for the business that was the pleasure of the night.

She stepped back into the room, slid the door shut and thought it through again. It was the best course of action. She couldn’t wait for others in hope.

‘Michiko,’ she called out to the apprentice.

The patter of feet quickly echoed from the adjoining room.

‘Yes, Onēsan?’

‘Mi-chan, I need to ask a favour of you. But I must warn you, it’s not an ordinary task. If you don’t feel comfortable I’ll understand. It concerns my father.’

‘I’ll do whatever you need,’ said Michiko without hesitation. ‘What is it you’d like me to do?’

Katsuyama smiled. She’d been lucky with her apprentice. When Michiko opened her mouth it was usually to speak sense, and scheming and sycophancy were not among her traits.

‘I know you’re close to Kaoru’s apprentice,’ she said, referring to the only tayū in Yoshiwara who could come close to her own allure. ‘Despite the fact your mistresses fight like cat and dog.’

Now Michiko smiled.

‘That’s right. Namiji was in Yoshiwara when I arrived. She helped me settle in.’

‘I’d like you to speak to her,’ said Katsuyama. ‘Lord Genpachi favours Kaoru. I want to know if there’s been any loose pillow talk between them. Can you do that for me?’

They both understood the significance of the request – Genpachi’s dispute with her father’s lord had led to her family’s downfall. Theirs had been a hatred passed down from their fathers. It had concluded when Genpachi out-manoeuvred his foe and had him stripped of his land, his title and everything else he possessed. He had been forced to shave his head, retreat to a temple and live out his days as a monk.

If he had been made to commit seppuku his retainers and their families would have had to do the same. But they were lucky; his lesser punishment meant those who could find new positions were employed by other lords. The others, although now rōnin, were at least still alive.

For Katsuyama’s father it had been different. As senior retainer it had been decided his punishment should be more severe. His land was taken, his stipend removed and he had been banished from within sight of the castle walls. A proud and distinguished samurai, he had been reduced to working the land to eke out a living for his family. But the land had been ungenerous in its returns. That was when Katsuyama had taken her new name and gone to Tanzen.

Then her life had turned on a twist of fate. When the first shōgun consolidated the country, the samurai became warriors without a war. It had left them frustrated and quick to be drawn into fights. As they lost their status as protectors, ordinary townsfolk’s deference to them decreased and their own self-confidence grew. The two factors combined for a perfect storm and one had erupted in Tanzen. Its refurbishment in blood and gore gained infamy nationwide.

The bathhouses had borne the brunt of officialdom’s consequent wrath. But while it had spelled their end, it had marked a new beginning for their most famous employee. Katsuyama had moved to Yoshiwara the same month, bought in on a contract that would feed her family for a significant time.

‘Of course,’ said Michiko. ‘Is there anything in particular you expect to hear?’

‘No. I mean, I don’t know. I can’t think who else would wish ill of my father so I have to believe Lord Genpachi is involved. I don’t expect him to discuss the matter with a courtesan, but there may have been conversations that seemed unusual or people mentioned she hadn’t heard talk of before. Please try to find anything that stands out.’

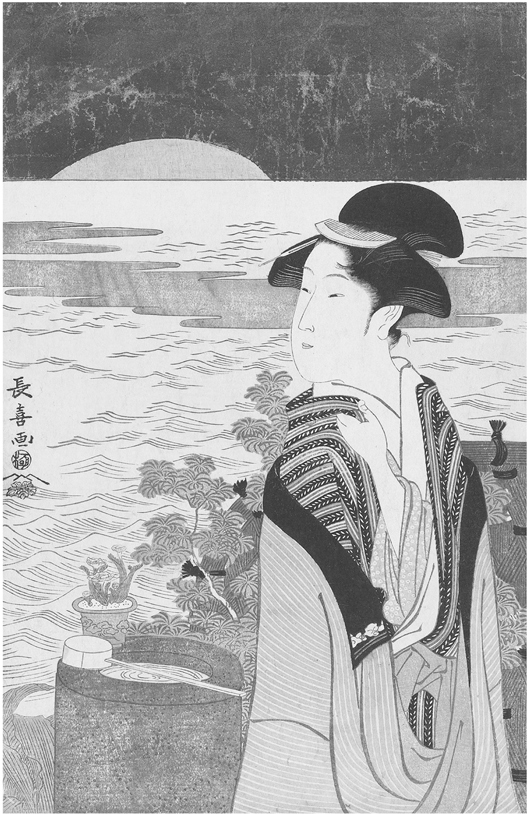

She stood as two assistants adjusted her kimono, plain white until painted with a swirl of flowers, birds and clouds at her favourite artist Moronobu’s hand. Her hair she insisted on finishing herself, tying the wide white silk ribbon in its jaunty loop to the right.

‘Hold the mirror a little further up please,’ she requested of one of the assistants.

She cocked her head, wiggled her hips and then smiled to let them know it was just right.

‘Is everyone ready?’ she asked.

‘Yes, ma’am, except Michiko. No one knows where she is.’

‘Don’t worry about Mi-chan. She can catch up.’

As she spoke, Michiko burst into the room, her face flushed. Katsuyama cut in before she could blurt out anything better said when they were alone.

‘Mi-chan, get yourself ready. We can talk on the parade.’

They made their procession from her residence to the ageya, the houses where only the highest ranked courtesans entertained. In front, a male servant held a lantern and led the way. Behind were two maids who could double as entertainers depending on the number and desire of her guests. Obasan was at her left, there as a chaperone to take care of Katsuyama’s interests and those of the house. And to her right, Michiko, included for her innocent repartee and the energy of youth.

Michiko had been sold by her impoverished parents when she was nine. She would have to work until she could repay the sum; no easy matter considering its size and the expenses endlessly accrued. Yet in many ways she was lucky. She had escaped starvation and done her duty by helping her family do the same. She had also been attractive and spirited enough to be bought by a leading house.

Katsuyama shivered as they passed small alleyways to the left and right. In these, the workers’ servitude swallowed the best years of their lives. The girls who worked in their bordellos weren’t courtesans. Their training wasn’t in words, culture and art. They were prostitutes confined within their houses, who served customers at their owner’s desire and suffered brutality at his hand.

Michiko would learn from her and become a courtesan of the highest ranks. Then she would have the chance to pay off her contract or have it bought out by a client instead.

Katsuyama’s attention returned to the parade. Crowds had gathered for her as they always did. On a whim she kicked her heel a little harder and the red silk of her inner kimono swirled up to reveal the white skin of a rarely seen thigh.

‘So, Mi-chan,’ she said, through barely moving lips. ‘What is it you have to tell me?’

Michiko pretended to support Katsuyama’s arm so she could turn slightly and speak unseen.

‘You know Mizuno, the rōnin who now owns a dry goods store in Nihonbashi? Apparently he met Lord Genpachi in Yoshiwara not more than a month ago. For part of the evening all the servants and courtesans were sent from the room.’

It was intriguing. Theoretically, all from street-sweeper to shōgun were equal within Yoshiwara’s walls, but it was still unusual for a daimyō, a lord of Genpachi’s standing, to consort with a merchant, a person of the lowest social class. And Mizuno was curious in himself; after being reduced to a rōnin no one knew how he had progressed so swiftly to his astonishing wealth.

The question was how to find out more. But it was a question for another day. The procession had reached the ageya, its sumptuous facade resplendent in the sun’s evening glow. She needed to bring herself back to the present. She would return to this quandary the following day.

The screams reverberated through the house and brought Katsuyama rushing down the stairs. Servants crowded around Michiko, who was as quiet as they were loud. She sat unmoving and ashen-faced.

‘Mi-chan, what is it?’ she called out above the furore.

Michiko was unable to say anything but held out her left hand. It was covered in blood.

‘Call for the doctor at once and bring water and cloth to my room.’ Katsuyama softened her voice and put her arm around her apprentice. ‘Mi-chan, come with me.’

Upstairs, they sat on the tatami by the low table. Katsuyama held the young girl to her and gently stroked her hair. She had wound a piece of cloth around the base of Michiko’s finger in order to stem the bleeding. She’d then washed and wrapped the wound. Just the very tip had been sliced off, leaving a straight edge where it should have been round.

‘Mi-chan, what happened?’ she coaxed.

Her apprentice snuggled into her.

‘I went back to talk to Namiji, to see if there was anything else I could find out. But we were overheard. Kaoru was furious. I was dismissed but I snuck back around the side. They beat Namiji horribly and told her she’d never work for them again. They’re going to sell her to a brothel, even though there are good houses that would happily buy her out.’

Michiko sobbed. She’d retained some of her innocence but not enough that she didn’t know what lay ahead for her friend.

‘But what happened to your finger, Mi-chan?’

Michiko looked up at her and then back down at her hand as though she had forgotten anything was wrong.

‘I was returning from their house when I was grabbed and pulled into an alley. One man held me from behind and another brought out a knife. He told me that I and any others should leave our enquiries alone. If not, he would take my hand the next time and if that didn’t stop us he would cut out my heart.’

Katsuyama hugged her tightly.

‘I’m so sorry, Mi-chan, I had no idea anything like this would happen. But you needn’t worry – there won’t be a next time. I’ll take care of everything from here. As for your friend, I’ll do all I can to prevent her going to a brothel, even if it means extending my own contract to buy her out.’

Michiko hugged her back but Katsuyama scarcely noticed; her mind had already moved on. They had miscalculated badly if they thought she, a samurai, would be scared off at such little threat. Now she knew she was on the right trail there would be no holding her back.