‘So what makes you think we know anything about your girlfriend? I believe we move in different worlds, do we not?’

I’d been dumped face down on the floor in the middle of a small, smoky office. There was a low coffee table just beyond my head and a compact sofa to the right. It took a moment before I realised I’d curled into a ball. I reluctantly uncoiled and lifted my head. A man sat at the other end of the table with one leg crossed over the other in a way that seemed more European than Japanese.

‘Are those fingers?’

It wasn’t the answer I’d intended to make, but an instant reaction to the contents of the jars on display behind him. A huge paw-swipe knocked me flat and set my right ear ringing.

‘Answer when the boss asks you a question,’ a voice thundered from behind me.

‘That’s OK.’ I looked up to see ‘the boss’ hold out a restraining palm. ‘Let’s hold off beating him senseless for the moment. I’d like to hear what he has to say.’

I guessed he was in his early sixties but he could have passed for younger. He was as smooth as Nat King Cole’s voice; his high cheekbones and taut skin set off by a suit so beautifully tailored it could have been an extension of him.

‘May I speak?’

I was terrified of doing anything that might be considered a transgression.

‘I wouldn’t have asked the question if I didn’t want you to answer,’ the boss said. ‘Why don’t you sit on the sofa though – the conversation feels somewhat awkward with you on the floor.’

Before I could move I was hoisted by the scruff of the neck and dumped on the sofa. I rubbed the side of my face as I tried to summon the courage to speak.

‘So, why would we know anything about your girlfriend?’ he asked again.

‘I think she came to see you a few weeks ago,’ I said in a meek voice. ‘At least it may have been you. It was a Takata-gumi office.’

His expression didn’t change.

‘Her name’s Chōshi Tomoe.’

He still didn’t react. I was too scared to say anything else.

‘You’re Chōshi Tomoe’s boyfriend?’

In the circumstances it seemed even more implausible than normal.

‘Yes.’

He deliberated a moment.

‘Come into my office – no, it’s OK,’ he turned to the others. ‘Just … ?’

‘Ray desu.’

‘Just Ray-san. I don’t think he poses a great danger, do you?’

I followed him through a door on his right into a far more luxurious room. He made his way towards a polished hardwood desk with plush leather chairs at its front and back. The shelving to the side was made of the same wood and filled with books, a decanter and cognac glasses, and a statuette that looked like an award. My feet sank into deep pile.

‘I hope you’ll excuse the squalor,’ he gestured at the exquisite room. ‘Our head office is in Ginza but I spent my formative years here. I have a soft spot for the place, hence the satellite study. Please, sit down.’

While his courtesy was preferable to his henchman’s aggression, it didn’t put me at ease. I didn’t know much about the yakuza but I couldn’t see why a local boss would refer to his own office as a satellite. And if he wasn’t a local boss that implied he was someone very senior. His air and the way he was talking made me wonder if he might even be Takata himself.

He reached for the decanter.

‘Would you care to join me? Hine Antique – it’s excellent but quite difficult to find in Japan.’

I’d have nailed a shot of paint-stripper. I nodded.

‘As for the fingers, I can only apologise. It’s another of these ridiculous traditions I’m trying to ease out. The idea we can no longer proclaim criminality and sever body parts hasn’t been easy for everyone to grasp. Of course, it’s important we retain an ability to use force, but we’re no longer just the rogues of the past. We’re bankers, art dealers, businessmen – missing digits don’t sit well with these roles.’

He was too suave to be exasperated but a hint of frustration edged through in his voice.

‘The grasp of tradition holds strong though. Yakuza all want to see themselves as chivalrous outlaws, men of honour who help the weak and bring down the strong. I appreciate one needs a business identity and on many levels ours works well, but the Robin Hood-isms and counter-productive customs can be tiresome.’

He looked over as though waiting for me to play a part. I wasn’t in a state for enlightened contribution.

‘But you’re a yakuza. Isn’t that what it’s all about?’

His face was a mixture of bemusement and disdain.

‘It’s about business. It’s about money and power.’

‘But I thought you kept crime among yourselves? That’s why you’re accepted – you help local communities and so on?’

‘You believe so? Maybe in the pre-war years, I don’t know; that was before my time. Now? We go where the money is and we make it from whomever we can. We’re accepted because we pay off or scare the people we need to. Those who don’t accept us are dealt with in other ways.’

His look became curious.

‘Do you know anything about the yakuza?’

‘Not really. They came up in my studies but it wasn’t quite the focus of my degree.’

‘Well, you’ll hear about righteous outlaws and Edo-period codes of honour, but in truth we come from gamblers and street peddlers. No great heroes, just people looking to make a living who weren’t afraid to bend a few laws.

‘Their trades and that mindset created opportunities and when they took them their interests expanded and their cash piles grew. Before long people began approaching them for loans.

‘But there were others who looked to appropriate their assets more directly. This meant they had to develop their security as well. Lo and behold, they found this was a service that could be monetised too. They continued to diversify and their small enterprises became empires.

‘Then Japan opened up in the Meiji era. But the internationalist spirit wasn’t just about letting others in – we’d seen what the Europeans, Americans and Russians had achieved by venturing overseas. Their pillage of Asia gave ideas to people here. And when their views were opposed, who do you think was unleashed? In return for silencing the doubters the yakuza shared the spoils of war.’

I couldn’t see what this had to do with Tomoe but I reasoned that any rapport I could establish would lessen my chances of being fed to the monster next door.

‘But the, er, the result of the war must have changed things?’

‘It did. The nationalists were hammered but the occupation proved hugely beneficial to us. Rationing meant anyone able to get hold of goods had the means to a fortune and the American army had a wealth of supplies. We teamed up with them and the money flowed in.

‘As time went on and the region’s politics became more complicated, the US decided they liked communists even less than those they’d deemed guilty of war crimes. So they released the latter and helped them create the LDP party which, as you know, has remained in power almost ever since.

‘So yes, the war did change things. It enriched the yakuza and put our political partners in charge.’

It didn’t seem a very healthy foundation for democracy. It was possible we thought differently on the matter so I kept my mouth shut.

‘It was a glorious time. Japan was an empty page and there were exceptional leaders to write its next chapters. But despite expanding the organisation on a massive scale, our interests for the most part remained the same. It wasn’t until later that they really evolved. Scandals in the sixties led to laws that restricted us in our traditional fields. Fresh pastures were sought in response. Finance, trade and business manipulation were added to a base of labour, moneylending and vice. The eighties bubble was like an injection of steroids – that’s when we peaked.’

He glanced over his cognac.

‘There’s no need to look so worried. These aren’t dangerous secrets – you could easily find them online.’

I was more concerned about sitting before the head of Tokyo’s yakuza. After that, I was fretting about how to get past his henchman in the next room. I made an effort to look less anxious all the same.

‘So the yakuza, the nationalists and the government – they’re actually one and the same?’

‘No, we’re not the same. We have our own specialities and we operate in different spheres. We sometimes have our difficulties too. But you could say we’re fingers of the same hand.’

‘Surely Japan isn’t that corrupt?’

My stomach knotted even as I said it. It wasn’t the affinity-building prompt that I’d meant.

‘As opposed to whom?’ he said sharply. ‘The Americans? Their government was a partner throughout. It put the people in place and funded them for decades.’

He raised his eyebrows.

‘And you, you’re English?’

Despite the past and repeated efforts of my university teachers my pronunciation clearly wasn’t as good as I thought.

‘You think there isn’t the same complicity in your country? What about your companies, your politicians? We found HSBC an excellent place to do business, so this isn’t a criticism. But when they were caught laundering money for Mexican cartels, their chairman was made a minister in your government – he wasn’t hauled into court.

‘We’re all the same; you just have different ways. You’re the fingers on the other hand.’

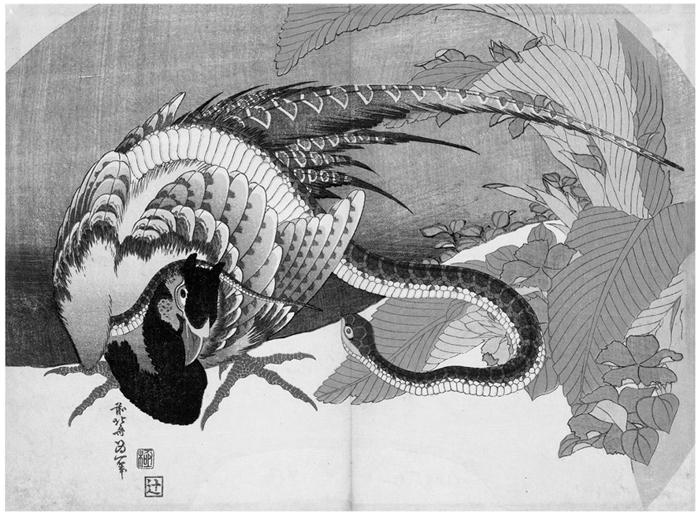

He held me in his stare. I felt like a pheasant eye-to-eye with a debonair snake.

‘But I’ve strayed from the point. I was trying to explain my situation. You see, the generations before me were blessed with opportunities, chances to do things differently, ways to leave their mark. I’ve contributed to the industry but I haven’t fundamentally changed it. I’d like to redefine it for the generation to come.’

His eyes sparkled. He looked less gangster boss, more CEO working on a final master strategy prior to his succession plan.

‘You see the crackdowns in the sixties – they helped the oyabuns, the bosses; they forced them to explore and expand. But the recent laws have been far more restrictive and we’ve already reached into every corner we can. So now, we face decline – our numbers are down and revenues are going the same way. I want to turn that around. And while doing so, make sure the Takata-gumi comes out on top.’

He stopped. I let him ruminate lest he be in the middle of his big idea. I was starting to wonder at what point comfortable silence becomes awkward when he spoke again.

‘I’d like to thank you. This isn’t a conversation I can have with others in the organisation and my wife is bored of hearing the same song. You’re very easy to talk to – I’m pleased you could come around.’

He made it sound as though I’d popped along for a cup of tea instead of being bludgeoned around the head and dragged in. It seemed an opportunity to depart in a manner similarly suited to social norms.

‘Oh, it was my pleasure. It’s been fascinating – thank you so much for your time. But I’m sure I must have taken too much of it already. I should really get out of your way.’

He ignored the hint.

‘So now we must turn to your girlfriend.’

I have to admit, my focus had moved from the quest for Tomoe to saving my own life. I wasn’t sure how to react now Takata brought it back.

‘I take it from your visit you no longer know where she is?’ he asked.

I nodded.

‘And you think that I might?’

I shook my head.

‘I’m sure you don’t,’ I said, desperate not to offend him. ‘I just thought, perhaps, you might have an idea of someone who would know or you could possibly ask questions to find out. She was very upset by her father’s passing and may have had some outlandish ideas. I’m sure she’s calmed down now though. She’ll have realised how ridiculous they were.’

I managed to say my piece but it was a battle. A large part of me just wanted him to dismiss me so I could escape.

‘We had nothing to do with the disappearance of your girlfriend. You’re right, she did come to talk to me, although she was more conventional – she made an appointment to see me in Ginza and received a more cordial welcome as a result. Your girlfriend is a lady of culture, an artist, someone deserving of respect. We spoke, she said some things – things I was willing to accept from someone of her stature – and there were areas in which I could enlighten her as well. But that’s all there was. If she’s missing that saddens me and I truly hope she returns safe and well. But I have no further connection to her. It isn’t my affair.’

‘But—’ I said, my mouth prompted by the memory of her when she returned, the distress his ‘enlightenment’ had caused.

‘That’s all there is,’ he interrupted, the finality in his voice putting it at the scarier end of suave. ‘I had no compulsion to tell you that much. It was out of respect to your girlfriend and because I enjoyed our talk. But there’s nothing else. It’s time for you to end your investigations. It’s time for you to leave.’

It was both exactly what I wanted to hear and precisely not. I started to get up.

‘You need to leave Japan. There’s nothing for you here.’

That stopped me. It’s an unusual experience being thrown out of a country, even more so when it’s at the hands of a gangland boss. But there was something else. His choice of words seemed to imply something had happened to Tomoe.

‘What do you m—’

‘I would suggest you make a fulsome apology to Kurotaki as you go out. You must realise that face is everything for a yakuza. To be insulted by another yakuza is bad enough; to be insulted by a non-yakuza is even worse. For the person to be non-Japanese – and I hope you realise this is a mentality I’m describing and not my own view of the world – it’s completely unacceptable.’

‘But—’

‘Thank you once again for coming by.’

It was said with finality. My time was up. Trying to extend it would only anger a man whose whims could mortally affect my life. I bowed, thanked him and, stomach churning, made for the door.

Kurotaki and the other yakuza turned when I stepped out. I bowed to a right angle before they could react further, apologising profusely and showing the total submission I assumed was necessary to have any chance of walking out. When I righted myself, Kurotaki was looking over my shoulder. I sensed Takata’s presence and realised it was only his say-so that would save me. He must have given it silently because it was Kurotaki who spoke.

‘Get the fuck out of here now.’

This time I took his advice.