‘Who killed him?’ I asked, shocked. I couldn’t say our relationship wasn’t complicated but this was a disturbing new turn. ‘What happened? Have you called the police?

‘Yakuza,’ she spat. ‘It happened two weeks ago but I just found out. I couldn’t even go to his funeral.’

The words were cold and hard where normally her voice was sweet and soft.

‘But what happened? What are the police doing?

‘Nothing!’ Her lip curled. ‘“Our investigation concluded this was an unfortunate event, a suicide. Please accept our condolences for your sad loss,”’ she mimicked bitterly.

It was a branch of normality. I grasped at it. ‘So it was a suicide? He wasn’t murdered?’

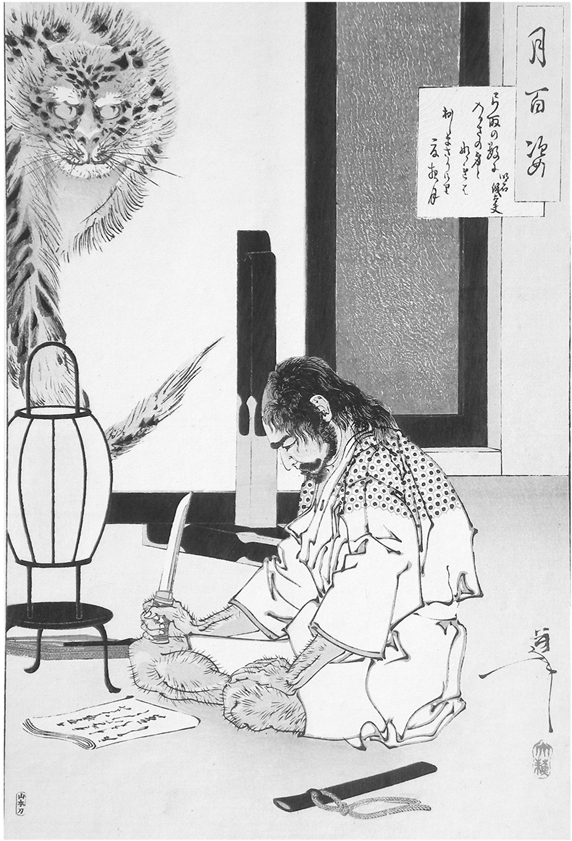

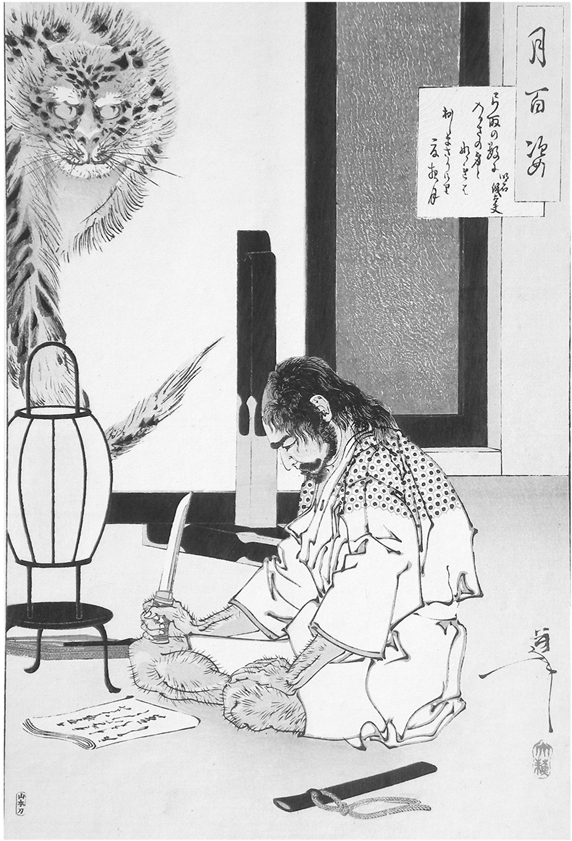

Now she aimed her contemptuous look at me. ‘Chōshi is a samurai name. We’re descendants of a high-ranking family. If there was a serious matter of honour my father might have taken his life. But to jump from a bridge with a note saying he was unhappy?’

Her disdain prevented her from continuing. I wasn’t going to contest her. I didn’t know her father. As for the samurai thing – a ruling class of warriors who lived by a code of honour formed by art and war that reached its zenith in death? It had seemed best to back away when she pulled out that card.

But if I’m honest, the real reason I held back was the look on her face. It scared me.

‘But why are you so sure it was the yakuza?’ I asked tentatively, stroking her shoulder. ‘If you’ve got information maybe you could go to the police and get them to reopen the case?’

‘The police?’ she snapped. ‘The police are part of it. Why else would they conclude the investigation before it could even start? Why would they pretend they could find no relatives, not contact me, and have him cremated within a week?’

I was hoping it was a case of incompetence but I didn’t venture the thought.

‘But what makes you think it was the yakuza?’ I asked again as gently as I could. ‘Was he, uh, did he come across them in the course of his work?’

She stopped as she was about to answer and a half-smile brought a glimpse of the old Tomoe.

‘Ray-kun, I appreciate you trying to be sensitive, but no, he wasn’t a yakuza. And while you can never know what they’re into, there was no reason for them to be involved in his work. He’d had some debts but they were paid off. He was just a regular businessman. He had no connection to crime.’

‘So there shouldn’t be any reason for them to kill him should there?’ I asked softly, not wanting the other Tomoe to return. ‘Why are you so sure it was them?’

Her face became a mask again. ‘I know someone who knows that world. He’s the one who told me about my father’s death.’

We were back on the murder track rather than the sad but reassuring suicide. I had a bad feeling about where it would go.

‘Could you not put him in touch with the police?’ I asked, trying to lead her away.

‘I told you the police are involved,’ she said, scary Tomoe once more. ‘He’d be in danger if he went to them.’

‘So what are you going to do?’

‘I’m going to find out what happened. That’s why I need you to go to soapland.’

It wasn’t what I wanted to hear.

‘Then I’m going to make them pay.’

Tomoe had a complicated family dynamic. I didn’t fully understand it, which wasn’t surprising given my lack of understanding about much of her life. But whereas the rest was an intriguing enigma, I knew some difficult facts lay behind this particular door. She’d allowed me a glance in once and I hadn’t been anxious to open it again.

We’d gone away for the weekend to Hakone, a town in the mountains south-west of Tokyo, famous for its onsen hot springs. We’d spent the afternoon strolling the hills of the open-air art museum, then soaked out our exertions in an onsen before heading back to our traditional ryokan inn.

When we had finished the feast brought to our room, the table was cleared and thick futons with puffy duvets rolled out on the tatami mats. Another eye-opening experience later and we were spent; minds and bodies entwined around a perfect day.

‘Ray-kun,’ Tomoe said, her limbs draped around mine. ‘Doesn’t your family worry about you living so far away? Don’t they mind you changing your career?’

‘I don’t think they were delighted by the latest change, but that was more because it wasn’t exactly my choice to leave. And I’m sure they’d prefer it if I was in England, or at least somewhere closer than here. But I’m not a kid any more and they accept that. Once you leave the nest there’s no knowing where you’re going to end up.’

I thought for a moment.

‘I suppose they just want me to be happy. And if being out here makes me happy, then, for the most part, they’re happy too.’

‘Mm, that sounds nice …’ she drifted off.

‘It’s not like that with you?’ I ventured cautiously.

‘It’s different.’ She was silent a short while. ‘My mum died when I was a baby. I’ve seen pictures and my dad told me about her – apparently she was a lot like me. But I don’t have any memories of my own.’

She sighed and stared out at the stars that twinkled through a gap in the sliding door. A chorus of frogs serenaded us with lusty song from the garden below.

‘And your dad?’ I prompted.

She stayed as she was, as though she hadn’t heard me, but two rapid blinks – to prevent a tear or clarify a thought? – made me leave the subject alone.

‘We had a falling out,’ she said softly, just as I was starting to drop off. ‘He’s very traditional. He never showed his emotions even when I was a kid, but he doted on me in his own way. I think he saw my mother in me and that made him love me even more.’

She paused.

‘But I upset him.’ Her voice wavered. ‘I did something to let him down and he can’t forgive me. We haven’t spoken for over two years.’

‘But he’s your dad,’ I said. ‘I don’t know what you did to upset him but you’re his daughter. It’s not the kind of love you can switch off.’

‘I’m sure he does still love me.’ She was now on the verge of tears. ‘But what I did, the kind of upbringing he had, the kind of man he is – he can’t just pretend everything’s fine. He isn’t to blame. It’s my fault.’

I brushed the tears from her cheeks.

‘Even if it is, I’m sure you can do something to put it right, something to show him it was a mistake.’

I said it to soothe her and bring a less melancholy end to the day. But then, before I could stop myself, I asked, ‘What did you do that was so bad?’

She buried her face in my neck. ‘I’m sorry, I can’t talk about it. Not yet.’

I stroked her hair, silently cursing myself.

‘No, I’m sorry. You don’t owe me an explanation. But I’m here if you do ever want to talk about it.’

With that ineffectual piece of counselling we’d slowly drifted off to the sound of the frogs under the moon and the stars. Drifted off to a place of melancholy, but a place of peace nonetheless. A place it would have been ridiculous to even contemplate murder and revenge.