‘Dickhead. What do you think you’re doing playing detective without keeping us informed?’

I’d only got a few stops into the journey home before my phone rang. Kurotaki.

‘Kumichō told me to look into things, to be proactive. That’s what I’m doing. If you don’t like it you need to take it up with him.’

My irritation at being denied the promised support was mixed with guilt at my snooping and made me more strident than was probably wise.

‘You motherfucker! You’re bold over the phone, aren’t you? I’ll—’

‘I was just doing what I was told,’ I said hurriedly. ‘I tried to speak to Kumichō but he didn’t take my call.’

‘You little bitch! What did I tell you about Kumichō? You don’t deserve to have him know you’re alive. You don’t call him up like a schoolgirl when you’re in the mood for a chat.’

‘OK, I’m sorry.’

‘You need something on this, you get in touch with me. If you can’t reach me, call Sumida.’

‘OK, OK, I will,’ I said, my annoyance surfacing again.

‘Don’t give me attitude, you stupid fuck. You still don’t get it, do you? This isn’t just to help you. There are people who want to kill you and I’ve been told to keep you alive.’

I smartened up with the reminder.

‘I’m sorry. Really, I will. But in this case I’m not sure it would have been a great idea to have you along.’

Kurotaki acknowledged the point with a grunt. ‘We still could have accompanied you down, kept eyes on you there.’

‘It seems like you had plenty doing that already.’

‘You know what I mean. Next time you want to do something get in touch first.’

I decided to put his word to the test.

‘OK, the next time’s now. I need to see the ex-president of the Kamigawa plant.’

I reasoned that if there was a conspiracy it could be revealed either by something he could tell me or information hidden in the documentation of the site.

‘When?’

‘As soon as I can. There isn’t much time until the AGM.’

‘OK – he’ll see you tomorrow. Be at our office at eight.’

‘Don’t you need to check with him first?’

‘Don’t question me. Get to the office first thing.’

He hung up. I settled back in my seat and started to doze. My phone rang again, drawing more dirty looks.

‘Where the fuck are you?’ demanded Sumida.

I was starting to yearn for the days before mobiles.

‘I’m on a train.’

‘What are you doing on a train? You’re meant to be at Horitoku’s.’

‘What’s Horitokus?’

‘He’s a person. A horishi.’

He sounded exasperated. I didn’t feel much different.

‘What’s a horishi?’

‘A tattoo master,’ he said impatiently. ‘Where are you? I’ll pick you up.’

‘Wait a minute. Why am I going to a tattoo master?’

‘You’re getting a tattoo.’

‘Hold on, if I want a tattoo, I’ll get a tattoo. If someone else wants me to get one they can discuss its merits with me first. You don’t just arrange it and not even tell me until after the time it’s meant to start. It’s—’ I was lost for words. ‘It’s just not what you do.’

‘Are you finished?’ he asked, having paid no attention.

‘What?’

‘Good. Now shut up and tell me where you are.’

I glanced at Sumida while he drove, the first time I’d paid him proper attention. This was significant in itself – despite being distinctive he somehow went under the radar. He wasn’t huge like Kurotaki but at over six foot and broad he was still large for a Japanese man. He carried his bulk athletically, with lithe movements like those of a cat. He didn’t have the yakuza crew cut either; his hair was long and bundled on top of his head. Not that this was in any way effeminate – he looked like a Chinese outlaw from centuries past.

I realised my mind was wandering. There were more important matters at hand.

‘Why am I getting a tattoo?’

‘The boss wants you to.’

‘Yes, but why does he want me to?’

‘He likes tattoos. You’re a yakuza. Yakuza get tattoos.’

Sumida wasn’t hugely communicative; perhaps his voice required an output of energy that couldn’t be wasted on chit-chat. He was, however, the most intriguing yakuza I’d met. While the others were loud bravado and crudity he kept his counsel, the Michael Corleone to all the Sonnys running around.

‘I have to get one?’

‘Yeah.’

Perhaps taking pity on me he offered a tit-bit.

‘Keep the receipts.’

‘What?’

‘Make sure you get a receipt.’

‘A receipt?’

‘Yes,’ he said patiently. ‘They’re tax-deductible as a business expense.’

‘Wait a minute – I have to pay? I don’t even want one.’

‘Whatever. Just remember, they’re expensive and it’s worth claiming back the tax.’

Curiosity got the better of my outrage.

‘How do I do that? Put down I’m the first, unwilling, English yakuza and I’m being forced to pay for a tattoo I don’t want as an essential part of my work?’

‘I wouldn’t phrase it exactly like that in your returns, but essentially yes.’

I was flabbergasted. I tried to think of an analogy.

‘It’s like a burglar claiming for a ladder after he’s robbed a house.’

He took his eyes from the road.

‘It’s not like that at all. Things have gotten trickier recently but we’re still a legal entity. It’s perfectly reasonable to claim expenses on the legitimate things we do. I’ve heard some mizu shōbai clubs have even tried to claim on protection money.’

‘And they got it?’

‘I don’t know,’ he replied. ‘I can’t think their chances were great, but apparently they gave it a go. Anyway, make sure you keep the receipts.’

Asakusa had retained the buzz it had had the last time I lived in Tokyo. Even streets that had seemed rundown and tired now thronged. Small stores grilled senbei, rice crackers, out front while their neighbours hawked ceramics, knives, kimonos and other traditional goods. Kabuki stars peered down from lamp-post placards, suggesting here at least they had retained their allure. Altogether it felt as though Asakusa had left the rest of Tokyo to look to the future. Its eyes remained on its Edo-period halcyon days when it had been the entertainment centre of Japan.

Sumida parked the car and we walked through the narrow, bustling streets, the covered ones in particular creating the mood of a bazaar. After making our way from the centre into quieter roads, we stopped in front of a residential block. It was typical of Tokyo’s more functional kind, the type that makes one question whether an architect was ever involved.

Its lift battled our weight to the seventh floor.

‘Konnichiwa.’

A man in his early twenties was waiting for us. He bowed politely. Sumida barely lowered his head in return.

‘Please, follow me.’

As he took us down the hall I wondered again at the transformational effect of Tokyo doorways, the worlds they let you into so often at odds with the utilitarian visions outside.

The walls of the apartment’s front room were crowded with photos. I leaned forward to look more closely at one of a sepia-tinted old man who I presumed was Horitoku’s master. He was stripped to a fundoshi, loincloth, his body an intricate swirl of tattoos.

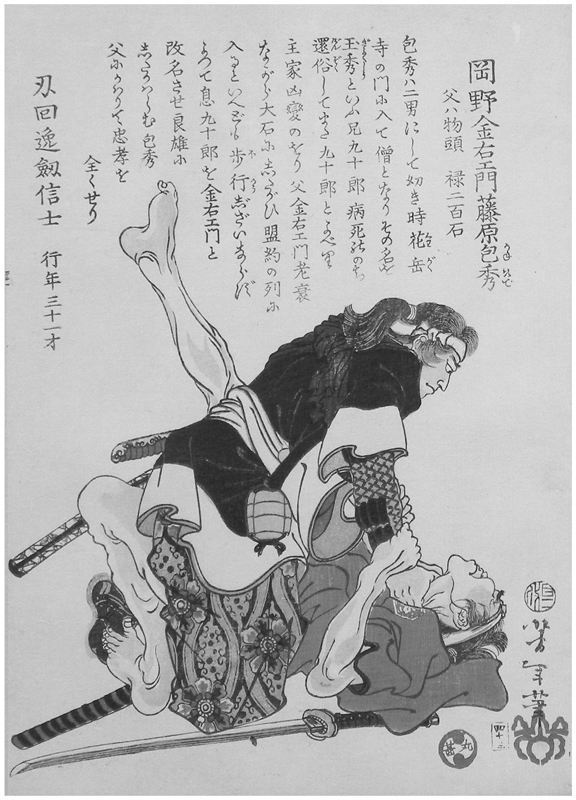

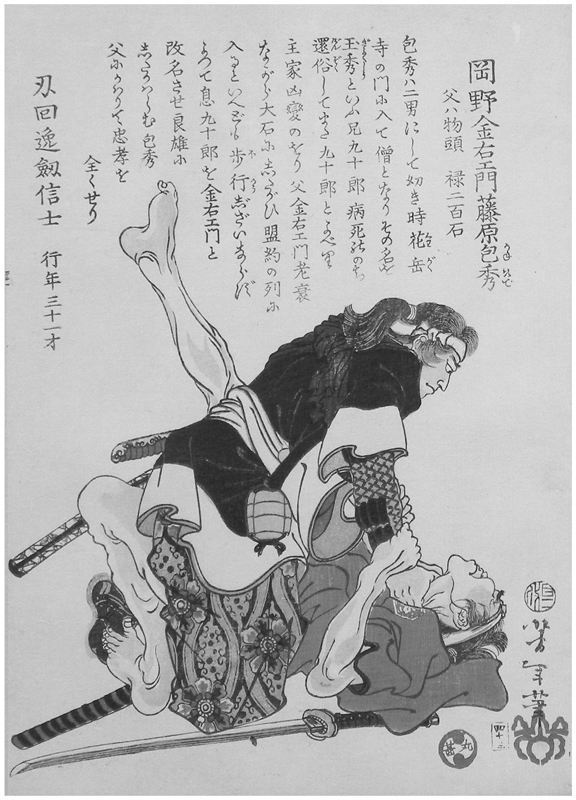

Impressive as he was, he paled beside the colour pictures around him. There were dragons writhing on skin, more realistic than the legends on which they were based; samurai and outlaws poised to attack, bursting with life after centuries in slumber; phoenixes prepared for fiery comebacks; deities as menacing as their hosts; and courtesans so beautiful they almost compensated for these men.

Displays of virtuosity that were more like special effects than tattoos.

They also seemed very big.

‘I don’t have to cover my whole body, do I?’ I whispered to Sumida.

‘Shut up.’

The young man, presumably an apprentice to the master, had just returned with Horitoku.

‘Sensei, konnichiwa.’

Now Sumida bowed, and bowed deeply. I followed suit. We received a greeting that was polite but less formal.

‘Please excuse us for being late,’ said Sumida. ‘We will of course pay for the time.’

I stiffened.

‘But could I request we extend the appointment? My oyabun is keen for Ray to make good progress with his tattoo.’

Horitoku agreed and they indulged in some pleasantries, Sumida continuing to speak formally, Horitoku replying with the relaxed Japanese a superior is allowed. They briefly discussed the tattoo Sumida was apparently receiving.

‘So, did you have something in mind?’

Horitoku had turned to me. He was quite short but had a reassuring solidity and a dapper pencil moustache. His civility and self-assurance made me feel more comfortable than I probably should have.

‘I’m not quite sure yet,’ I replied – I didn’t see any benefit in revealing how I had been coerced at the last minute into being there. ‘Would it be possible to look at your work first?’

Horitoku’s apprentice was already scuttling for photo albums and folders of illustrations. I looked through them in awe. They were even more magnificent than the ones on the wall. As the designs danced on the flat of the page, I could only begin to imagine how they looked on a moving figure.

A dragon wriggled towards me. It wasn’t clear what he was meant to represent. He might have been leering as there was certainly something sinister about him. But it was impossible to be sure of his intentions, as though layers of complexity lay behind the dangerous facade. It seemed appropriate.

‘I like this one.’

I turned a couple of pages to see a geisha, or perhaps it was a courtesan. I looked closer and did a double take. It had to be a courtesan, whatever their differences in dress. I knew this because it was Tomoe. Her grace, her charm, somehow even her sparkle had been captured on this illustration prepared for an unknowing recipient’s skin.

‘And this,’ I said, my mood turning melancholy at the coincidence.

Except it proved a lot less coincidental than I thought. A few pages later I saw it; the black fox, dancing and snapping around her ankle. Protecting her, she’d said. I wondered again if I was too late to take its place.

‘Where did you get this picture?’

‘I took it.’

‘You knew my girlfriend?’

‘I know her,’ he corrected. ‘Yes.’

‘How do you know her?’ I asked, wondering what more of her I hadn’t known.

‘We can talk about that while I work. Is there a design you want?’

‘Yes. The dragon, Tomoe, and her fox.’

He fixed me with a stern look.

‘Horimono, Japanese tattooing, doesn’t work like that. There are rules.’

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know. How does it work?’

‘You choose a design, and assuming I think it’s appropriate, I create it on you. It’s not a pick and mix.’

A new turn-up in a week of surprises. I didn’t want to be culturally insensitive but if I was going to be tattooed against my wishes, I thought I should at least have a say in what my permanent marking would be. As I pondered how to express this to a man Sumida literally bowed before, Horitoku spoke again.

‘The reasons for the courtesan and the fox are clear. Why do you want the dragon?’

‘It’s a little complicated. It has some relevance to my recent experiences and one or two present threats.’

‘Threats? You know dragons usually have protective associations or represent good luck?’

It was yet another thing I didn’t know. For me, they represented fire-breathing danger and fodder for Saint George.

‘Weren’t there some dangerous ones as well?’

There must have been because he concurred, albeit with a little reluctance.

‘It’s not the way it’s normally done, but I suppose you’re not a normal customer,’ he said, as much to himself as to me. ‘Maybe it’s worth trying something a bit different this time. It would be nice for your girlfriend too.’

I kept quiet as he mulled the breach in protocol.

‘OK, if that’s how you’d like it,’ he said eventually. ‘But I’m going to add a firefox as well. That will be her protection for you.’

I wasn’t sure how that worked, but the way things were I’d take whatever help I could get.

‘Please,’ he directed me towards a towel-draped foam mattress laid out on the tatami floor. ‘I have to get the stencils but then we’re ready to start.’

‘We don’t need to discuss it further?’

‘No. From now on you just lie down.’

Despite my reservations, I had faith he knew what I wanted better than I did. He probably didn’t, but I needed someone I could lean on, someone to trust.

*

‘But of course I know her,’ he said, not acknowledging the sharp intake of breath and the stiffening of my body as the needles first struck. ‘We’re both of the ukiyo, the floating world.’

‘What do you mean?’

I managed to get the question out only after biting back a yelp. Talking wasn’t made any easier by the fact I was laid out on my front, my chin and forehead propped up on foam blocks to create the best line for my back.

‘Ukiyo-e. Pictures of the floating world. She’s a master of paper; I’m an artisan on skin. Of course we met,’ he said, as though it was the most natural thing.

‘But don’t you mainly tattoo yakuza?’

I wasn’t an expert in horimono, but I knew anyone with traditional tattoos in Japan was assumed to be a gangster.

‘It was like that for a while but not any more. The crackdowns mean many want to be inconspicuous and the recession’s affected them too. The oyabuns don’t pay nowadays and the junior ranks don’t have the money to front up.’

He shifted slightly to improve the angle for his attack. The temporary relief only shifted my focus from pain to the overall situation – the enormity of the thought my body was being permanently changed with something I had no desire to have.

‘But just because our clientele have sometimes been rough at the edges, that doesn’t make it any less of an art. Horimono go back to the early 1800s. Hokusai helped make them popular and it was a series of tattooed outlaws by Kuniyoshi that made them really take off. Kuniyoshi wasn’t satisfied just with woodblock prints either. He created designs for horishi and was even tattooed himself.

‘So, you see, ukiyo-e and horimono are one and the same. They’ve been hand-in-hand from the start.’

‘I had no idea they had such a grand heritage.’

‘Don’t get me wrong, it was always a bit rebellious but it was legal, a badge of honour for the Edo-period working class. It was the Meiji government who made it a crime – they were scared foreigners would think it barbaric. After that, you had to break the law to get one and that put some people off. The stigma remained even when the Americans legalised it post-war.’

He said all this above the noise of the tattoo machine that was making a disconcerting whine behind my head. It pitched slightly higher when moving between me and a thimble of black ink at my side, then buzzed with the anger of a hornet when the needle was driven into my skin.

In less sensitive areas it felt like someone had jabbed me with a toothpick and was dragging it sadistically across my back. In other places it felt like a probe had been attached to my nervous system, sending my body rigid other than the uncontrollable twitching of my toes.

Horitoku was entirely oblivious to the effect.

‘The yakuza connection only came about because of the gangster movies in the sixties. They always had a chivalrous hero strip down to battle his adversaries at the end. People didn’t associate horimono with yakuza before then, but afterwards it was the first thing they thought.

‘It turned out the yakuza loved all of this and the numbers getting tattooed absolutely boomed. Now, I’m not going to complain about the people who pay me, but if you want to identify when horimono’s image problems started, you need look no further than then.

‘It was never just about them though,’ he added. ‘Firemen, artisans, tradesmen and geisha all have traditions of getting horimono. They kept coming too.’

He stopped talking as one area seemed to require a particularly keen focus, as though he was not just inserting ink but trying to drill down to the bone.

‘There are many cultured minds who’ve supported us. Like your girlfriend. That’s why I gave her her tattoo.’

He paused from his needle torture momentarily, giving me the opportunity to respond.

‘Why was the fox her protector? She never told me.’

Come to think of it, I’d never asked. I’d just thought it looked incredibly cool.

‘It was the kami, the deity, of Yoshiwara,’ he said. ‘Katsuyama-chan wanted a protector just as her predecessors had.’

He delivered this information as though it were matter-of-fact.

‘What – who?’

‘Katsuyama,’ he said. ‘You know about the original Katsuyama?

‘No.’

‘Katsuyama was the first great tayū of Yoshiwara. Yoshiwara was one of the three main pleasure quarters of Edo Japan.’

The last part I knew. It was everything he had said before it that had me confused.

‘Initially, the courtesans of Kyoto and Osaka were considered the greatest, the most refined. Katsuyama was the first to turn eyes to Yoshiwara.

‘She wasn’t even a courtesan originally. She was a bathhouse girl, an entertainer in the competition outside Yoshiwara’s walls. But she was so beautiful, so charismatic, that people came from all over to see her. Her whims and fancies would spark fashions and start artistic trends.’

He wiped at something I hoped was excess ink rather than blood running down my side.

‘But the bathhouses weren’t popular with the bordello owners. They weren’t strictly legal so the authorities didn’t care much for them either. One day, there was an almighty ruckus at Katsuyama’s bathhouse and they took the opportunity to close them all down.

‘Katsuyama’s stock was so high by then that The Great Miura, the most prestigious of all the Yoshiwara houses, took her on as a tayū. It was unheard of for someone to be promoted straight to the highest rank.’

Something had been nagging since I’d spoken to Tomoe.

‘Weren’t they were called oiran?’

‘Oiran were a lower grade of courtesan that came later. They came to prominence when standards dropped and the tayūs faded away. They’re the ones you see most often in the prints.

‘Anyway, when Katsuyama made her entrance everyone came out to watch. Even the other tayūs stepped onto their balconies, convinced she would embarrass herself or at least secretly hoping she would. But she raised a storm.

‘At the time, courtesans often wore their hair down. Katsuyama bound hers up with a white ribbon and the fashionable ladies of the day immediately took on the style. It’s still named after her now. Careful!’

He made this last comment because I’d turned my head.

‘Yes, your Katsuyama paid homage to it but there was more to her than that. You know Japanese arts often have succession names? You’ve got the Utagawa line in ukiyo-e, the Danjūrōs in kabuki, the names of the sumō stablemasters. It was the same for courtesans. But in over three hundred years there wasn’t anyone to live up to the name Katsuyama. Ka-chan was the first.’

I wondered how many people were intimate enough to call my girlfriend by the affectionate ‘chan’. My stomach tightened as I wondered if Horitoku had been more than a friend.

‘What happened to the original Katsuyama?’ I asked, partly to take my mind from the thought but also in case there were any clues.

‘Well, for the good there was in Yoshiwara there was also bad – the courtesans were indentured and that isn’t anyone’s idea of fun. But Katsuyama was different. She came to Yoshiwara on her own terms and somehow dictated when she’d get out. No one knows what happened to her, but three years after she first graced Old Yoshiwara she was gone.’

It was a nice story. Unfortunately, it wasn’t much help.

‘And what do you know about Tomoe, or Katsuyama II?’

‘I know that when they decided to resurrect the tayūs, they searched the length and breadth of the country and found the most beautiful and cultured women in Japan. And that even then Ka-chan stood head and shoulders above the rest.’

It was touching – if I closed my mind to their activities beyond the arts – but it wasn’t exactly what I meant.

‘What do you know about where she might be now?’

He stopped abusing my back for a moment.

‘I’d love to be able to help you. I’d do anything if I knew where she was or there was a way I could find out. But I’ve told you all I know. I saw her three months ago at an ukiyo-e exhibition and I haven’t seen or heard from her since.’

*

‘OK, that’s the outline done,’ he said, getting up and stretching. ‘We’ll start on the shading next time.’

‘That’s it – just the back?’ I asked, pleased the assault was over but feeling sore and strangely tired.

‘You can get more done if you like but your boss wanted something started quickly. So we’ll begin with the back and you can take it further from there.’

‘No, no, that’s OK. The back’s great,’ I said, relieved, although a part of me was disappointed I wouldn’t be totally transformed as the men in the pictures had been.

‘You’ll get a slight fever and you’re going to be tender for a few days. Take plenty of showers and put on a bit of lotion to stop it drying up. I’ll see you at your next appointment.’

I almost took my cue to leave but I couldn’t help myself. As much as I liked him and had strangely enjoyed the preceding hours, the thought had been gnawing at my insides.

‘Tomoe, you, er … ?’

He regarded me for a moment and then saw where I was going.

‘No, our relationship wasn’t like that.’ The rebuke was clear in his voice. ‘We were fellow artists, we admired one another, but our relationship was professional. Any feelings beyond that were like those of a father and daughter.’

‘Of course, I’m sorry – my mind’s all over the place. I shouldn’t even have asked,’ I said, delighted that I had. ‘See you next time.’

I was surprised to bump into Sumida having a cigarette by a no-smoking sign outside.

‘You didn’t have to wait for me – I’m good to get home on the train.’

‘I don’t think so,’ he said as we walked towards the car. ‘You’re a valuable commodity and anywhere there’s a risk – like at a horishi’s slap-bang in an area notorious for yakuza – you’re to be accompanied. So anyway, what did you get?’

I explained, only to find that he’d stopped.

‘You told him to change his designs?’

‘No, I just asked him to combine a couple.’

‘And he didn’t throw you out?’

‘I was very polite about it.’

He shook his head and started walking again. ‘You’ve got a thing for trouble, don’t you?’

He continued before I could protest.

‘He’s a cultured man but you need to watch your step – Horitoku Sensei’s scarier than most yakuza. For my first three years he didn’t even speak to me. I’d go in, wait for him to wave me over and then lie down so he could work. To him I was just a canvas paying for the privilege of his art. And don’t think I complained. He’s close to Kumichō – he did his bodysuit way back. You don’t mess with Horitoku Sensei. I’ve heard some scary stuff.’

Before he could explain why I should be terrified of the first person I’d met recently who I thought might be kind, we got to his car. It was a dark blue Nissan Teana without darkened windows, pimped-up alloys or any other ostentation, which made it entirely unlike the average mid-ranking yakuza’s car.

‘What is it that makes me a valuable commodity?’ I asked, returning to Sumida’s original point. ‘I don’t want to undersell myself, but I can’t think of any way I’d be of use to the Takata-gumi.’

‘You won’t get many arguments on that. There must be something for Kumichō to take you on-board but for the rest of us you’re just a pain in the arse. No offence.’

I was offended. I’d been trying to keep my head down precisely to avoid pissing off a group of scary gangsters.

‘But I’ve hardly even been to the office. Apart from you giving me a lift today, I haven’t been much trouble have I?’

‘It’s not you personally, it’s what you represent. You know about the situation with the Ginzo-kai?’

‘Who?’

He looked at me to see if I was being serious.

‘Shit, you really don’t know anything.’ He shook his head. ‘The Ginzo-kai are the biggest yakuza group in the country.’

‘I thought that was us?’

‘No, we’re the biggest in Tokyo and eastern Japan. The Ginzo-kai were founded in Kobe, but about ten years ago they decided they wanted to expand east. It didn’t go down too well with us or the other gangs.’

‘Surely you could just kick them out?’

‘That would be a great idea if they weren’t nearly thirty thousand strong. There’ve been a lot of clashes but they’re too big to simply boot out.’

‘So what’s the situation now?’

‘They have bases in Tokyo, and while we don’t get along, we coexist. You’ve got to realise there’s been a lot of pressure from the law-makers in the last five years. If we have an all-out war everyone suffers.’

‘But what’s any of this got to do with me?’

‘They’re the ones that tried to get you. They’re the ones we’re protecting you from.’

This was getting ridiculous. I was insignificant, a very average English teacher. I hadn’t even been worthy of my girlfriend. How could I be a central figure in the battle between Japan’s two biggest gangs?

‘But I’m Takata-gumi now. We have to coexist, you said.’

‘You’re right, but for whatever reason they seem keen to get hold of you and it looks like they’d been willing to suffer some disharmony for that.’

I didn’t like the way that sounded.

‘But you’re just the tip of the iceberg,’ he continued. ‘Because of you things have got more tense and that’s uncomfortable for everyone. But it was bad even before you turned up. Until this year the Ginzo-kai had been sticking to the spots they had but recently they’ve been encroaching on our turf. For some reason, instead of dealing with them, Kumichō’s been holding us back. That kind of thing makes people restless and then you come along – not much fucking good for anything as you put it—’

‘That’s not quite what I said.’

‘—and it’s like adding insult to injury. We’ve got the other yakuza laughing at us.’

I didn’t know what to say. It wasn’t great for my self-esteem. I had an unpleasant thought.

‘Kumichō’s position isn’t under threat, is it?’

He thought for a moment, a moment longer than I would have liked.

‘No,’ he said finally. ‘It’s too early yet. But it’s not a good situation. We’re getting squeezed by the Ginzo-kai and people are starting to twitch. Something’s got to happen and it needs to happen quick.’

I mulled the possibility of my protector disappearing to leave me between two packs of dogs.

‘What do you think about it?’

‘I think Kumichō’s the smartest out of everyone,’ he said after a pause. ‘If he ever gets taken out it won’t be because of something as obvious as this. So for my money, he must have something worked out – for us and for you. But I don’t know, I’m still young in the business and there’s a lot for me to learn. He’s the man to learn from so I’m happy to sit back, watch and wait.’

Sit back, watch and wait while the most powerful gangsters in the country plotted to capture and kill me. I was extremely unhappy to do the same. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a choice.