That I was in Japan wasn’t the result of a long-term life or career plan. The seeds of the move had been sown during what I thought was just another working day in London.

‘Ray, thanks for making the time,’ said Dave as he ushered me in. ‘Please, sit down.’

I closed the glass door to his office and sat at the acrylic table. Opposite, a lap-top and iPhone gleamed from his desk in front of floor-to-ceiling windows. Advertising offices are as ubiquitous in their soulless chic as they are in the unique differentiators claimed on their identikit websites.

‘Is everything all right?’ I asked. ‘You seemed a bit stressed when I saw you earlier.’

‘Yes, yes, it’s all fine,’ he said. ‘Well, it is and it isn’t. We’re turning a corner with our finances but revenues are still a bit ropey and there are some tough decisions to be made before we’re out of the woods.’

‘That sounds ominous.’

‘Well, yes. I mean no. I mean … well … look, we’ve just had a board meeting and we have to do some restructuring. And …’

His eyes roved the office beyond the glass wall, seeking escape from the task he was faced with. Failing to fit it, they settled back on me. ‘… and your team’s got the lowest profitability. And, well, it means we have to lose headcount.’

My heart sank. Headcount. I’d never considered it an adequate way to describe the foundation on which a person’s hopes, dreams and dependencies are based. Especially now that person seemed to be me. As Dave went on it became clear this was a limited restructuring effort, one that was particularly ‘precise’.

‘Am I the only one being let go?’ I asked, too crestfallen to be angry.

‘Well, right at the moment, yes. Unfortunately, profitability on your account is the weakest in the group and we’ve had to make some tough decisions.’ Dave was prone to management-speak when under pressure.

‘But it’s only one decision, isn’t it? There aren’t any other changes being made?’ A thought flashed in my mind. ‘You’re not getting someone in to replace me are you?’

‘Ray, we can’t be sure what’s going to happen long-term on your part of the business …’ He shifted uncomfortably. ‘Look, from an HR and management point of view, I can assure you this is a restructure. You’re on three months’ notice. You’re going to get that plus another three, assuming you agree. But you can leave as soon as you’ve done your handover. That’s a pretty good settlement for a redundancy caused by the adverse economic climate.’

He paused.

‘And, of course, that’s the truth. But if we were to meet as friends over a drink, I might tell you that you’re an extremely smart guy whose intelligence seems incompatible with advertising. You can beat me hands-down in a debate but you can’t land a campaign when everything’s been handed to you and I’ve got no idea why. But, assuming we were in that non-working environment talking as friends, I’d say you’re getting a great opportunity to sit back for six months and work out how to make the best use of your brain.’

I slumped in the Charles Eames chair.

‘Didn’t you do Japanese Studies at uni? And you lived there too?’ Dave asked. ‘You always seemed fond of the place – you even speak the language, don’t you? Why not head back for a while?’

It had seemed as good an idea as any as I tried to pick up the pieces.

I met Tomoe in a bar which, if I was to believe my friend Johnny, meant the relationship should only have been good for a one-night stand. But it wasn’t that kind of bar and Tomoe wasn’t that kind of girl. In fact, she was the kind of girl I’d never have thought I stood a chance with. But our eyes had met and there had been enough in the look for me to summon the courage to talk to her. And somehow, out of all the men in Tokyo, she’d seemed to find something appealing in me.

I should point out she wasn’t getting a dud – I’d entered my thirties in good enough shape to allow my mother some pride not solely based on maternal love. But Tomoe was special.

She had these brown-black almond eyes that sparkled mischief and a smile that brightened your day. Her dress sense was faultless, accentuating the curves of her body in a way that was immaculate yet effortlessly cool. Then there was her lustrous, jet-black hair, which she tied with a white ribbon in an endless array of styles.

But her looks were the least of her. She was a force of nature, with a devil-may-care attitude that left you helpless to resist her desires. It was balanced by the sweetest disposition that she subverted with a sense of humour that was boisterous yet feminine.

She was almost too good to be true.

We spent our first date tucked away in a restaurant gem in Nakameguro I would never have found for myself. Just as when we first met, I found Tomoe so gorgeous I got butterflies. And just as when we first met, she offset the effect by being completely unaware of it. I was lured in by the melt of her eyes and had to hold myself back from touching the unblemished skin on a forearm or where her neck met the top of her chest. Watching her as she spoke, I lost lines of conversation to the thought of kissing her daydream-inducing lips.

The date went well enough for us to have another, then another, and a flurry after that. There was no fixed pattern – we might meet in a high-end, high-rise restaurant in Ebisu one evening, before going to a rowdy izakaya bar in Ameyoko the next.

Her sparkle and spark remained constants but they were the only things I could predict. Soft and caring when I turned up with a sprained ankle, she was equally spiky when a doorman questioned my suitability for a show – she only relented when he convinced her he’d been concerned I wouldn’t understand, his hurried apologies for not letting me demonstrate my Japanese slowly bringing her back from the boil. On other occasions she simply dazzled, whether sending currents of electricity sizzling through staid dance floors or bringing a sedate bar to life.

I could never be sure which Tomoe I’d meet and whenever I thought I’d pinpointed her character she’d surprise me by revealing another side. The constant sense of discovery intrigued and excited me. And it made me thirst to find out more.

It was on a trip to Ishigaki Island when we really clicked. Having spent time only on short dates so far, the long weekend let us get to know each other through relaxed conversation and the frenetic physicality that a new relationship charged by warm weather and skimpy clothing permits.

It had been Tomoe’s suggestion to go and it had taken me by surprise – a sleepy island hadn’t seemed a fit for her big-city style. It was only we got there, both of us slopping around in T-shirts and shorts, that I realised the easy-going environment suited her best. With me a fair way from the suave sophisticate I’d thought she’d admire, the idea of us as a couple suddenly made more sense.

The thought had struck me as we lay on miles of deserted golden sand at Yonehara beach. As we made our way back to our rental car, passing eyes drawn uncontrollably to Tomoe’s curves, the sense it made had seemed limited again.

Despite being a bachelor without ties or commitments, it had been surprisingly hard setting off to Japan. Having spent time away before, I knew I’d come back to friends doing much the same as when I left. But saying goodbye to my parents, who insisted on seeing me off, brought a lump to my throat and the sense of enormity that comes with major change.

Tokyo also disorientated me subtly – so similar to when I’d been there ten years before that its differences felt like optical illusions, like seeing something familiar through warped glass. There were new buildings and some areas had changed but it no longer had the ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ feeling of rapid advance.

There was still enough to throw me off guard – in an increasingly homogeneous planet it had remained one of the few places able to provide the jolt of a culture shock. Even normal things felt that little bit different, whether being bamboozled by the functions of a high-tech toilet or seen out of a barber’s by five bowing staff. Just as when I’d first arrived, it left me wondering if I hadn’t flown to another country but been transported to a parallel world.

My response was to seek familiar ground, finding a flat in Takadanobaba in the centre of Tokyo, just around the corner from where I’d previously lived. The students from nearby Waseda University continued to give the area its lively buzz, whether thronging the streets in daytime or drunkenly revelling through the night. They helped keep it pleasingly rough at the edges and ensured it retained a welcome affordability for such a central spot.

I quickly found work that wasn’t outside my comfort zone either. I contacted the high school I’d taught at after my degree and had a stroke of luck. Their English teacher had just left and they were delighted to take me back on a generous wage that saved them on agency fees. With days that ended at three o’clock, I had time to take on private students and still work fewer hours than I had in my office job. I might not have found the way to maximise my intellectual potential, but I was earning well with minimal stress.

With home and employment providing the reassurance of the old, I had the freedom to enjoy the excitement of Tomoe’s new. Add to that six months’ redundancy pay sitting in my bank account and life felt pretty good.

My financial comfort paled beside Tomoe’s resources, though, not that she seemed to care. She was certainly willing to spend her money, as her impressive wardrobe, perfectly coiffed hair and readiness to pay any bill could attest. But she never gave the impression she needed it. For her, being in possession of money seemed to be an unpleasant necessity that spending it could relieve.

The best description I could get for the job that allowed her this lifestyle was ‘cultural curator’. Rather than work for any specific museum or gallery, she was employed by a specialist agency that contracted her out.

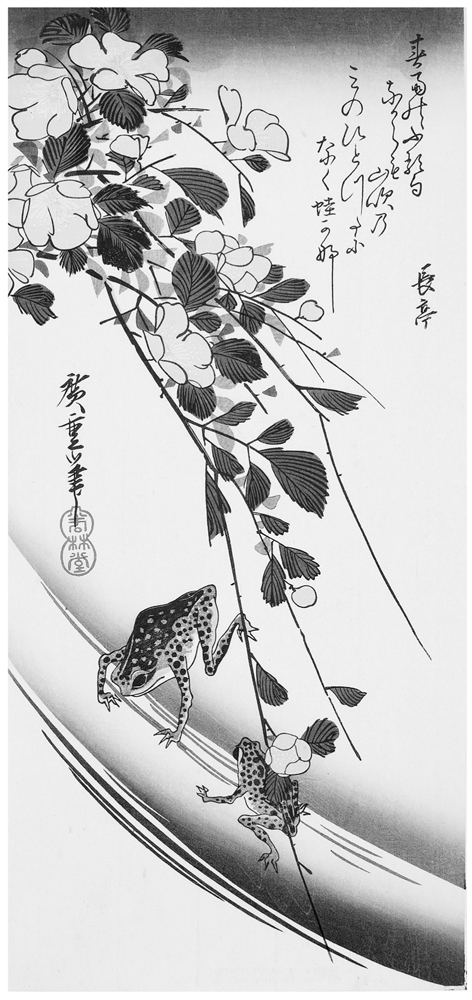

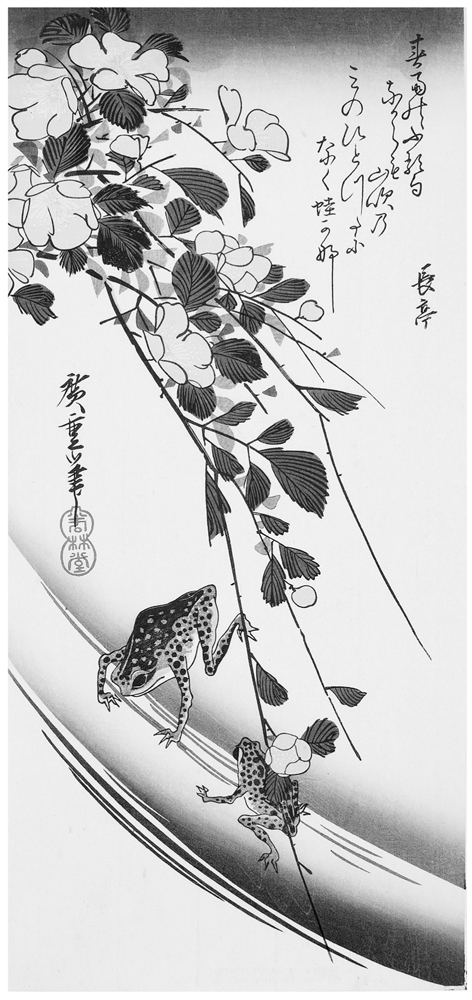

She was certainly impressive. A visit to her apartment would introduce you to the greatest ukiyo-e woodblock prints – a framed Hokusai leaned against a cupboard, a Kuniyoshi on her desk, a Yoshitoshi on the living-room wall. She could provide histories for all of them, accompanied by explanations of technique, artistic innovation and symbolism within the designs.

She might receive a text asking her opinion from a novelist one day, then have her view sought by a musician the next. Such was her span of contacts I learned to curb my tongue after offending her with an ill-informed opinion on a dancer who turned out to be a friend.

‘Why can’t I find you online?’ I asked her once.

‘What do you mean?’

‘I’ve googled your name but I can’t find a thing.’

‘Why are you trying to find me online?’ she said suspiciously.

‘There’s no need to be defensive. You’re my girlfriend. I just wanted to find out about the things you’ve done.’

‘You won’t find anything,’ she said, turning back to the kabuki theatre catalogue whose introduction she was writing. ‘Japanese artists and performers go by inherited names. It’s the same for me – even then I’m normally not announced. People in the industry know me, but there’s no reason the public should.’

Before we could discuss it further she was off, her whirr of energy taking her to an exhibition in Hokkaido this time.

Before I first went out, people talked about Japan as a losers’ paradise for gaijin foreigners, especially males. But I never found it was really the case. Admittedly, there were men with girlfriends they wouldn’t have stood a chance with at home. But the real catches tended to be on the arms of suave Japanese men. There was also the prospect of creeping into a higher social stratum, or getting a better package on an ex-pat deal with work. But I’d seen a bit of both and neither seemed the epitome of Eden to me.

Yet here I was, coming straight from the sack into an untaxing job that left me free of financial concerns. I had friends and a place to live that was convenient, even if it was a little compact. And if my girlfriend could be more elusive than the floating world in which she worked, it was more than compensated by a personality that matched her looks. In fact, her sense of mystery only attracted me more.

For all my doubts I might have been the mythical gaijin, the one winning in a losers’ paradise. It certainly felt like everything had come good. Unfortunately, when you’re at the top there’s only one way to go.