![]()

The Japan Journals

1947—2004

The Japan Journals begins with an evocation of early morning in Tokyo, 1947, not long after Richie‘s first arrival. It is based on early journal entries. Other sections of this early journal have appeared elsewhere, for example as the opening to Richie’s first novel, Where Are the Victors? (aka This Scorching Earth, 1955). The account of the destruction of Tokyo that follows this is taken from interviews and then given to one of the characters in the novel. For another memoir, In Between, Richie used pages about meeting a number of people. These are here reconstructed. There are also memoir reworkings of material that appears in different form in the Donald Richie Reader (2001).

winter 1947. Tokyo lies deep under a bank of clouds which move slowly out to sea as the sun climbs higher. Between the moving clouds are sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow of new-cut wood and the shining tile of recent roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburned, the dusty green of barely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of ornamental lakes. In the middle is the palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The smoke of early household hearths, of newly renovated factories, of the waiting, charcoal-burning taxis, rises and with it the freshness of late winter, the bitter yellow smoke of burning cedar shavings, the smell of breakfast: barley, sweet potato, roasted chestnuts. In the houses the bedding is folded into closets and tatami mats are swept.

Beneath the hanging pillars of the early rising smoke there is the morning rattling of night shutters thrust back into the narrow walls. Behind the banging of the shutters is the sound of wooden geta—the faint percussive sound of people walking—and the distant bronze boom of a temple bell. Jeeps explode into motion, and the tinny clang of the streetcars sound above the bleatings of the nearby fishing boats. Somewhere a phonograph is running down—Josephine Baker goes from contralto to baritone.

A distant radio militantly delivers the Japanese news of the day and a few MPs, still in pairs, roam the recently empty streets. A single woman, modest in bright red, knees together, maybe a geisha going home, hurries. Greer Garson luxuriates, her paper face half in the morning sun, and a man dressed like Charlie Chaplin, a placard on his shoulders, begins his daily advertising.

In the alleys, the empty pedicabs are lined up, and around the early alley fires the all-night drivers yawn and warm their hands while early farmers lead their laden horses into the city. An empty Occupation bus, with “Dallas” stenciled on both sides, makes its customary stops—the PX, the Commissary, the Motor Pool—but no riders are in it. Occupation women with khaki skirts, out early, try unsuccessfully to hail a passing U.S. 8th Army jeep.

The rising sun is now caught by the blank windows of the taller buildings and casts reflections—the silver flash of spectacles, a passing gold tooth, the dead white of a mouth-mask. The food shops open and the spicy bitterness of pickled radish mingles with the sweet stench of fish, mingles with the scents of the passing nightsoil carrier, his oxen and his cart.

The rolled metal shutters of the smaller shops are still locked but before the open entrances of larger buildings MPs stand and wait, their white-gloved hands behind their backs, their white helmets above their white faces. They stand in front of most of the Occupation buildings—the gray Dai Ichi Building, the square Meiji Building, the pale Taisho Building, the squat Yusen. To the south rises the box-like Radio Tokyo and, in all directions, the billets of the Occupation itself, the American flag floating above them.

The clouds drift out to sea and the city lies under the winter sun. The pedicab drivers go home, and the wives serve the morning soup. The sun and smoke rise into the air and the radios shout into the sky, while the streetcars rattle and the auto horns honk, and the fishing boats cry, and the railroads fill up the city.

The account of the destruction of Tokyo that follows is taken from interviews and then given to one of the characters in Richie’s novel Where Are the Victors?

Tokyo/Shinjuku, Winter, 1947. eighth army signal corps

He remembered the day. It was in a cool, sunny, unseasonably windy March [1945]. The children who had them still wore their furs. His two sisters, dressed alike in little fur hoods with cats’ heads embroidered on them, were sent off to school, and his father went to work next door at his lumberyard.

It was the third day of a leave from the Army. He had a new lieutenant’s uniform. His mother wanted him to stay near home and call on the neighbors. He wanted to walk around the city and show off his new uniform.

Their home was in Fukagawa, which was like no place else in Tokyo. The carpenters pulled their saws, and the logs floated in the canals. The factories blew smoke to the sky, and the dye from the chemical plants made the canals green as leaves. The Chinese ran restaurants and even the poor Koreans happily opened oysters all day long.

Some of Tokyo had already been bombed, but those few districts were far away, and the people in the rest of the city were not afraid. The radio said that the Americans dropped bombs indiscriminately and that there was no need to fear a mass attack as the radar would detect the intruders and give ample time for escape.

Just a year before Fukagawa had been bombed, but the damage had been slight. The bombs fell mostly into the countryside and people decided that the Americans were not very skilled in this important matter of bomb dropping. Fukagawa, in the suburbs, seemed as safe as Shinbashi, in the center.

[That evening] he heard the watchman at eleven when the call of the watch was interrupted by the air-raid sirens. Earlier in the afternoon, while at the movies, he had heard an alert, but the all clear had sounded immediately after.

Now he walked swiftly through Shinbashi Station and ran through the standing passengers, past the halted trains, to the top level of the station. He didn’t really expect to see anything. He only wanted to be soldierly.

He arrived just in time to see the sudden flare of massed incendiary bombs. It was Fukagawa. The planes were apparently traveling at great speed. It was impossible to say how many there were but it seemed hundreds.

A great ring of fire was spreading. The planes were so low he couldn’t see them and could tell where they had been only by the fires that sprang behind them. There was an enormous explosion, like August rockets on the Sumida River, and a great ball of fire fell back on the district. A chemical plant had been hit. Seconds later he felt the warm burst of air from the blast, miles away.

Later he heard that the planes had come in so low that they escaped the radar. The antiaircraft could do nothing against planes that near and that swift. The stiff March wind spread the flames and he later remembered thinking of the canals that cut through the section, and thought that people would at least find safety in the water. There would be water enough for everyone.

He didn’t remember how long he stood on the top platform of Shinbashi Station and watched the destruction of Fukagawa, Honjo, Asakusa, Ueno. But he remembered wondering why they were so selective—why not the Ginza, why not Shinbashi, why not he himself? He later remembered walking up the deserted streets past the closed motion picture house where he had been that afternoon. It was near dawn when he reached the bridge across the Sumida, the last pink of the fires replaced by the first pink of dawn.

There he saw those coming from Fukagawa. Most had been burned. They carried scorched bedding on their backs, or trundled bicycles with possessions strapped to them. They walked slowly and did not look at him as they passed. He wondered where they were all going and stopped an old man who told him that everything had been burned, and that everyone had been killed.

He walked across the bridge and finally reached Fukagawa. He could not believe what he saw. There was nothing. Nothing but black and smoking ruins as far as he could see. He had never known that so much could be destroyed in one night.

On the street he found a bicycle that belonged to no one and on it he started toward his home. But nothing looked the same. There were no streets any more. In cleared places were piles of burned bodies, as though a family had huddled beneath a roof that had now vanished. They seemed very small and looked like charcoal.

He peddled slowly along what had been a street. Long lines of quiet, burned people, all looking the same, came toward him. He didn’t know where to turn north to go to his father’s lumberyard. Nothing was familiar. He leaned his bicycle against a smoking factory wall and looked toward where his home should have been but wasn’t. The lines of the burned moved slowly by, and suddenly he began to cry.

After he had cried he looked at the people again and saw his younger brother coming toward him. They stood, looking at each other, amazed that such a thing could happen. His brother had spent the night at school because he had had to finish a war work project of some kind, and he had not heard about the raid until he woke up. Now he too had just arrived and didn’t know where their home was either. So in the growing light they began walking.

Troops had been brought in and were clearing the streets, or where they supposed streets had been. They shifted the bodies with large hooks and loaded them, one after the other, onto trucks. Often the burned flesh pulled apart, making the work more difficult.

[The brothers] walked on, past mothers holding burned babies to their breasts, past little children, boys and girls, all dead, crouched together as though for warmth. Once they passed an air-raid shelter and looked in. It was full of bodies, many of them still smoldering.

The next bridge was destroyed, so they decided to separate. His brother would go north and he south. It was the first time they had used these terms with each other. Usually they spoke of up by the elementary school or down by the chemical plant. His brother started crying and walked away, rubbing his eyes. They were to meet at their uncle’s house in Shinagawa.

He walked south to the factory sections. The chemical works had exploded and what little remained was too hot to get near. Some of the walls were standing, burned a bright green from the dye, the color of leaves. In a locomotive yard the engines were smoking, as though ready for a journey, the cars jammed together as in a railway accident.

There were some in the ruins still alive, burned or wounded. Those who couldn’t walk were patiently waiting for help by the side of the tracks. There was no sound but the moaning of an old woman. It sounded like a lullaby.

He saw only two ambulances. They were full of wounded, lying there as though dead. Farther on, prisoners of war were clearing the smoking ruins. They wore red uniforms and carried blankets to remove the dead.

Eventually he recognized the Susaki district. Yesterday it had been a pleasure center, with sidewalk stalls, music, women peeping from behind latticework screens. Now there was nothing. The houses, like all the decorations, had been made only of wood and paper and had burned almost at once. Now no one moved. He turned back.

The small bridges across the canals had been burned. He had to stay on the large island connected to Nihonbashi by the bridge across the Sumida. He looked across the canals and saw people still alive on the little, smoking islands. They shouted and waved, but there was nothing he could do, so he went on. Some were swimming across to the large island. They had to push aside others who floated there, face down.

In a burned primary school he saw the bodies of children who had run there, to their teachers, for protection. Later he learned that there were two thousand dead children in that school alone. They lay face down on the scorched concrete floor, as though asleep. The kimono of some still smoked. The teachers to whom they had fled lay among them.

It was past noon when, suddenly very tired, he walked back across the bridge to Nihonbashi where he took a trolley to Shinagawa. It stopped continually. It was filled with wounded. Others, less wounded, hung from the roof and the sides. He could have arrived sooner by walking.

At his uncle’s house he found his brother and, surprisingly, his uncle. The latter’s arm was badly burned. He had come home that afternoon, walking the entire distance. He told them about their family. They had been sitting at the table, his sister and himself. The younger girls had already gone to bed and his brother-in-law was at Susaki.

The first planes bombed around Fukagawa, and then closed the circle, making it smaller and smaller. It was hard to escape because it happened so fast. Almost instantly there was fire on all sides.

By the time the air-raid sirens had begun they heard the explosions, and flames were leaping up in the distance. The planes wheeled over them and the circle of fire was much nearer. They got the girls up, but by the time they were dressed the fire was only a block away. They tried to escape from the lumberyard but the little bridge that led to the Tokyo road was burning. So they climbed into the canal in back of the house.

Bombs were constantly dropping and finally one of them hit the neighborhood. The heat was terrible. Even the logs in the canal began to smoke. They watched the fire spread, in just a few seconds, to the storehouses and across the entire island. His mother and sisters held onto a log and began to cry.

Their uncle found a pan and dipped water over their heads and shoulders. The little fur hoods with cats embroidered on them helped protect the children for a while, but when the fur began smoking, he tore off the hoods and poured water directly on their hair. The half of the log above water cracked in the heat but he kept on pouring.

There he had remained until early morning. Around one, the fire burning around them just as fiercely as before, he became very tired. He tried to get a better grip on the log but found his arm so burned that it stuck to the wood. He was not able both to hold up his sister and nieces and at the same time continue to pour water on them.

They were very quiet and, he was sure, unconscious. His arm was so tired that he too must have lost consciousness. The pain of his arm’s slipping across the burning log woke him. The mother and two little girls were gone.

The next day he and his brother went again to Fukagawa. It was now filled with rescue workers. They found their canal and where their home had been. Everything was gone. Only the ground remained. They identified the house from its foundation stones. Near where the house had been they were removing bodies. He tried to find some of the neighbors but couldn’t—everyone there was a stranger. No one knew where his father’s workers were either. They had lived above the warehouse where the finished lumber had been stored.

Later he learned that thirty thousand people had been killed that night. Some said it was the unseasonable wind that had done the most damage. It spread the fire and heat. The explosions caused more wind until, about one in the morning, it blew through the flames at a mile a minute.

It was almost a week before the Emperor inspected the ruins. By this time the bodies had all been removed. Already the streets were being mapped and bright wooden bridges connected the islands. People said that the Army had delayed the Emperor’s arrival. They didn’t want him to see how terrible the fire had been. If he had, he would have stopped the war at once. But now, with a new week’s fighting begun, he could do nothing about it. It was the fault of the Army.

For the rest of the summer his brother lived with his uncle and he himself was sent to Tachikawa Air Base. Then it was August and the war was over. When he saw Fukagawa again people were living there once more. The main business was still lumber. Before the fire there had been over two thousand lumber dealers, but now there were only a little over a hundred. There were no chemical plants but the dye works had opened and the canals were green again. The Chinese restaurants were thriving as usual and even small Korean centers had sprung up. But now their old occupation—opening oysters—had been taken over the Japanese. It was about the only way to make a living in Fukagawa.

*

From the window of my billet, Kyobashi looks like Hiroshima—the same holes where whole buildings once were, the same odd empty spaces in what once was solid street. Further off there are more buildings standing, though separately, revealing that there was once something between.

At the Ginza crossing there are quite a few buildings standing. The Mitsukoshi Department Store, gutted, hit by a firebomb, even the window frames twisted by the heat. Across the street is the white stone Hattori Building, its clock tower with its cornices and pediments much as it had been.

There is not much else left: the ruins of the burned-out Kabuki-za, the round, red, drum-like Nichigeki, undamaged. At Yurakucho, on the edge of the Ginza, are a few office buildings and the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater, now renamed the Ernie Pyle.

Otherwise, block after block of rubble, stretching to the horizon. Wooden buildings do not survive firestorms. Those that stand were made of stone or brick. Yet, already, among these ruins there is the yellow sheen of new wood. People are returning to the city.

*

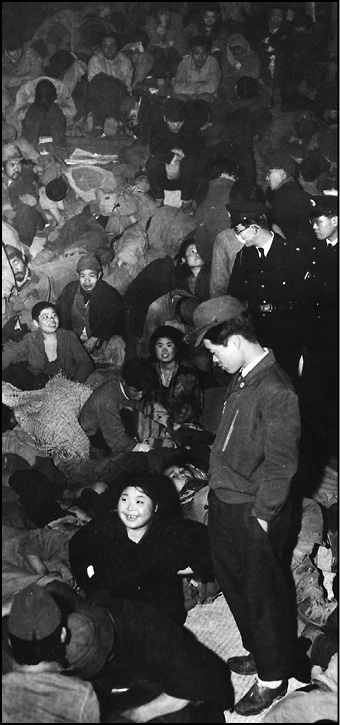

I have some photos taken last year in the subway corridors of Ueno Station. There, sitting or lying on straw mats or the bare concrete, are some of the thousands of the hungry homeless. Men, women, a few children,

In one photo, they are being inspected by two bespectacled policemen wearing mouth masks. Many of the people are dirty, and all wear remnants of what they had owned during the war: cracked shoes, torn blouses, battered hats, buttonless shirts. But no one looks sad.

Tokyo/Ginza, Winter, 1947. eighth army signal corps

Everyone is smiling—everyone except the policemen, and maybe they are as well beneath their masks. Smiling for the camera, making a good impression, best foot forward. Even in the depths of national poverty everyone remembers this.

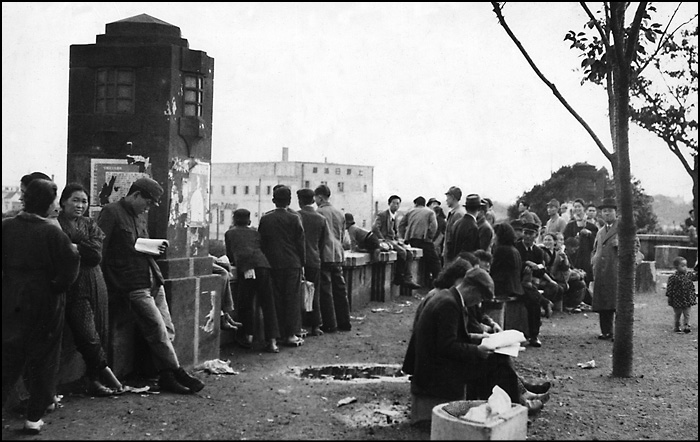

Up above, on the plaza, around the statue of Saigo Takamori, there are many more, sitting on benches and embankments—all of them waiting. Waiting, it seemed, for this too to pass so that they can get on with their lives.

Many have been and gone. The pedestal of Saigo’s statue is plastered with handwritten notices; I had someone look at the photo and read them to me. “Watanabe Noriko—Your Mother Waits Here Every Day from One to Five; Grandmother Kumagai—Shiro and Tetsuko Have Gone to Uncle Sato’s in Aomori—Please Come; Suzuki Tetsuro—Your Father Is Sitting on the Staircase to the Left—If You See This Please Come.”

The snows and rains have washed the older notices away and new ones are put up. They are like the votive messages left at shrines, invoking supernatural aid. Answered or not, they are left there until rained away or covered by notices of later misfortunes.

Though many entries were used in Where Are the Victors? (1956) and Public People, Private People (1987), a few unused pages remain. Among them are accounts of meeting the writer Kawabata Yasunari and the Zen scholar Suzuki Daisetz that are somewhat different from those in Public People, Private People and Zen Inklings. The continuations about Kawabata occur in their proper chronological places—9 January 1960 and 1 January 1973.

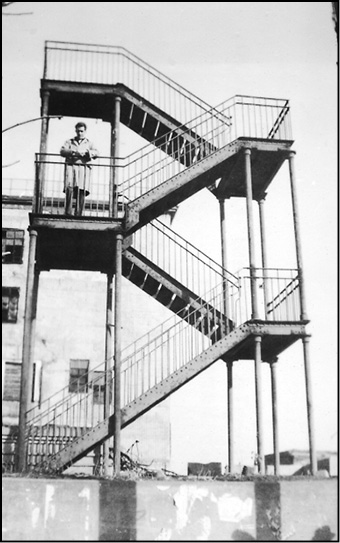

early spring 1947. The Sumida River, silver in the winter sun, glistened beneath us. We were on the roof of the Asakusa subway terminal tower, looking out over downtown Tokyo, still in ruins, still showing the conflagration of two years earlier, burned concrete black against the lemon yellow of new wood.

Ueno Subway Station, 1946. stars and stripes

This had been the amusement quarter of Tokyo. Around the great temple of Kannon, now a blackened, empty square, had grown a warren of bars, theaters, archery stalls, circus tents, peep shows, places where the all-girl opera sang and kicked, where the tattooed gamblers met and bet, where trained dogs walked on hind legs, and Japan’s fattest lady sat in state.

Now two years after all of this had gone up in flames, after so many of those who worked and played here had burned in the streets or boiled in the canals as the incendiary bombs fell and the B-29s thundered—now, the empty squares were again turning into lanes as tents, reed lean-tos, a few frame buildings began appearing. Girls in wedgies were sitting in front of new tearooms, but I saw no sign of the world’s fattest lady. Perhaps she had bubbled away in the fire.

Was that what he was thinking?—I wondered, looking at the avian profile of the middle-aged man standing beside me, outlined against the pale winter sky.

Ueno Plaza, 1946. stars and stripes

I had no way of knowing. He spoke no English and I spoke no Japanese. I did not know that Kawabata Yasunari was already famous and would become more famous yet. But I did know he was a writer because I had heard he had written about Asakusa and it was the place itself that interested me.

“Yumiko,” I said, pointing to the silver river beneath us. This was the name of the heroine of the novel, Asakusa Kurenaidan, which Kawabata had written when he—twenty years before, then about the same age I was, and as enraptured of the place as I was now—walked the labyrinth and saw, as he later wrote, the jazz reviews, the kiss-dances, the exhibitions of the White Russian girls, and the passing Japanese flappers with their rolled stockings. Yumiko had confronted the gangster, crushed an arsenic pill between her teeth, and then kissed him full on the lips.

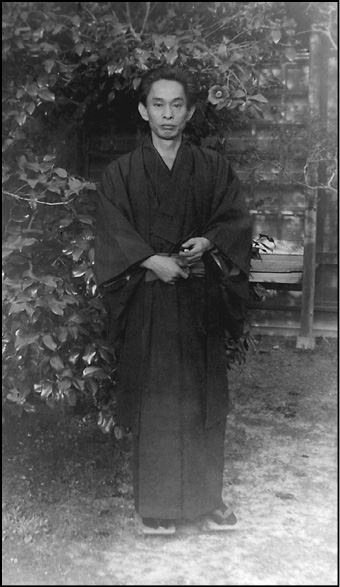

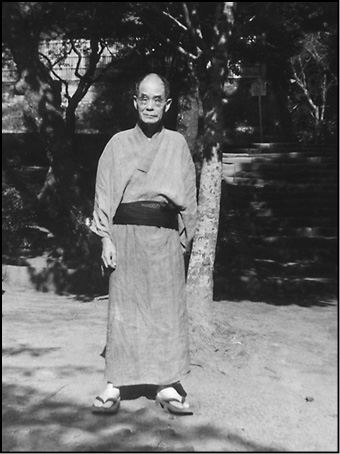

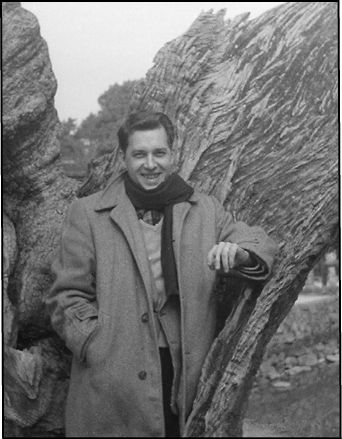

Kawabata Yasunari. donald richie

Perhaps he was thinking of this scene from his novel and of the lost Yumiko, tough, muscled, beautiful. Or, looking over that blackened landscape, under this huge white winter sky, he was perhaps feeling a great sorrow. All those lives lost in that blazing, roaring conflagration beneath.

Imagining a sadness that I assumed that I in his place would be feeling, I looked at that birdlike profile. It did not seem sad. Rather, Kawabata smiled, looked over the parapet and indicated the river.

This was where, I knew, the insolent Yumiko, having given the kiss of death to the older man (who, it transpired, was the lover of the local madwoman who, it turned out, was really our heroine’s sister), leaped through the porthole of the waiting boat, and sped away just as the water police arrived.

I knew all this without knowing any Japanese because as a member of the Allied Occupation I had translators at my command and had ordered an English précis of the novel. Now, looking at the author leaning over the edge, as had Left-Handed Hiko as he spied the escaping Yumiko, I thought about Kawabata’s love for Asakusa.

He had begun his book with the intention “to write a long and curious story set in Asakusa . . . in which vulgar women predominate.” It had perhaps been for him as it was for me, a place that allowed anonymity, freedom, where life flowed on no matter what, where you could pick up pleasure, and where small rooms with paper flowers were rented by the hour.

Did he, I wonder, find freedom in flesh, as I had learned to? It was here, on the roof of the terminal, that Oharu had permitted herself to be kissed—and more—by members of the gang and had thus earned herself the title of Bride of the Eiffel Tower. It was here that the Akaobi-kan, that group of red-sashed girls who in the daytime worked in respectable department stores, boasted about the bad things they did at night. Here that Umekichi disclosed that he had been raped at the age of six by a forty-year-old woman.

I wondered at all of this but had no way of asking. And now, chilled by that great sky, we went down the steep stairs, companionable but inarticulate. I had given him an outing; he had given me his bird’s eye view of Asakusa.

early summer 1947—kita kamakura. I stood before the great gate at Engakuji. The naked guardians grimaced, the carved eaves stretched above me, the roof soared and touched the pines. I was about to enter the abode of the Buddha, the world of Daruma, the land of Zen. I said the word softly to myself—the cicada-like drone of the syllable, the sudden halt of the consonant.

As I did a soft summer breeze struck the overhead pines. The needles rustled and from them fell a fragrance I had known as a child. Looking up, deep into that glittering green, I felt a memory surface, then turn and disappear before I could recognize it. But its passing brought a tear—just one, but real.

Then I was walking through the gate and into the temple, only an hour from Tokyo but already another world to me. In the silence I looked around—the main temple, the graveyard, what I took to be the zendo, a number of vegetable patches.

Around in back I found the small tiled-roof house. There I waited, letter and gifts in hand, waited for my teacher. I had read that the Zen adept waited all day—all night too, through rain, through snow. None of this, however, proved necessary, for the man I had come to see, who had not known I was coming nor that he was my teacher, soon noticed the large foreigner standing in the cabbage patch and came out on the veranda.

Suzuki Daisetz. donald richie

Suzuki Daisetz was a small man with steel spectacles hooked behind his ears, long hairs in his eyebrows, several moles. He was in a rumpled kimono and he cocked his head to one side as he peered at the intruder. He looked like an older man just awakened, but to me he was the picture of Zen: the fuzzy eyebrows, the high forehead, the childlike gaze—my patriarch.

He read the letter of introduction from the wife of a colleague, deceased in New York. And he received my offerings—Ritz, Spam, Velveeta, all that the Army PX could contrive. These the patriarch bundled away and then returned with a cup of tepid cracked-wheat tea for me. And there I was, finally, sitting on a cane chair on the veranda of my teacher, inhaling the smell of the tea and the odor of temple—mildew, mice, old paper. Deeply I breathed in the scent of what I took to be sutras, moldering and holy. Now my learning would begin—I had found my roshi.

Only I had not. It was not that he refused to be my teacher but that he refused to be anyone’s teacher. He was, he insisted, no matter the priestly resemblance, a layman. If anything he was a learner too.

This was told me in English accented by years in London. Still, he added, sounding like a British don, as a learner he had learned a lot. Yet, though he knew about mountain climbing he had never climbed Mount Sumeru.

He then waited for me to catch up. I knew that this was a fabled Buddhist peak, the scaled summit of which, I hazarded, meant satori. So this statement I took to mean that he had not himself yet reached what I fancied to be the terminal of Zen Buddhism.

One of the things he did know, however, he said, was that one did not climb mountains by merely looking at them. All too many people, he maintained, thought that Zen was some sort of mysticism, concerned with visions of the eternal and the like, that you simply sat and looked at it. This was not so.

Dr. Suzuki I later learned often defined things by what they were not. His remarks on Zen—gleaned by me over a series of Sunday afternoons, outside the pines sighing in the summer winds, inside the still smell of mice droppings—were entirely negative. The only positive description I received was that mountain climbing was hard work.

This was given with a glance in my direction. It had been ascertained that I never worked. Further, it was understood between us that I never would. Our bond, in that we had one, was that he did not either. Not if you defined work as zazen.

But that was what I had come for so he introduced me into the zendo and I had indeed sat for a time on my folded legs, my mind busy with what I had done that morning, what I would do later that afternoon, and wondering in what form my illumination would arrive.

This—my believing I was practicing zazen—went on for a time. The others, all Japanese, paid no attention to the interloper. They sat properly, eyes unfocused, backs straight, minds empty. They were on their way—traveling at great speed sitting completely still.

I, on the other hand, was shortly complaining that my legs hurt. Also I had questions, wanted descriptions and assurances. Consequently, after a short time, while others sat in the lotus position in the zendo, I sat comfortably on the sofa with Dr. Suzuki.

There he talked and I listened, hoping that learning would somehow rub off. In a way it did, because Dr. Suzuki eventually gave me an appetite for something he knew I could never eat.

Every Sunday I would appear with my crackers and cheeses, canned meats, peanut clusters—offerings from the PX for my sensei. These he would graciously receive and carry off to the larder. In return I would be given my cup of tea and a talk. It was always about Zen and I never understood a word. Or, rather, it was the words alone I understood—and sometimes the sentences, but never the paragraphs. Still, I was learning.

Other discourses I had heard were rational, logical, but Dr. Suzuki’s were something else. The process seemed associative, one thought suggesting another, apparently at random. But, as one idea followed another, I saw the randomness was only apparent. Each was attached to the other by the linearity they formed.

And as I listened I understood that there were other means of structuring thought, ways of thinking different from those I had always known and believed unique.

This was really all I ever learned from my teacher but it was a lesson of the greatest importance. Dr. Suzuki never gave me satori in exchange for my Velveeta, but he gave me the priceless apprehension of other modes of thought.

He also initially gave me a koan—the one about Nansen’s cat. This eminent Zen master saw two monks quarreling over the animal. He held it up and said that if they could give an answer the cat would be saved—otherwise not. Not knowing what to answer, there being no apparent question, they were silent and Nansen cut the cat in two. Later he told another priest about the incident. This person removed a sandal, placed it on his head, and walked off. Nansen then said that had he been there the cat would have been saved.

It is typical of my disposition that the first and only reaction was a concern for the unfortunate feline. And, of course, I too came nowhere near a reply since I did not comprehend that an enquiry was concerned.

Dr. Suzuki was patient. Either he saw something in me to interest him or he really needed the cheese and crackers. And so we continued until one early summer day with the cicadas screaming—zen, zen, zen—he smiled and said that I need not come again.

I understood his reasons but felt rejected. This he saw, stood up, and took a picture from the wall. It was a seated Kannon, black ink on white paper, framed in wicker, an oval picture of great beauty that I had often seen and admired.

It was also a genuine Hakuin. He told me to take it home with me and live with it for a while. He did not tell me why or for how long, but I understood that I would eventually return it to him.

The blow softened, I held Kannon on my lap all the way back to Tokyo. And as the train pulled from the Kita-Kamakura station I seemed to smell again the pines, and thought about that vanishing thought that had surfaced and disappeared. No longer feeling sorry for myself, clear-eyed, I patted the picture.

Some months later, already autumn, I was again on a train—a streetcar, rounding the corner at Ueno Park. Suddenly I again smelled the great pines of Kamakura. The scent, strong as the smell of the sea, swooped upon me, and the forgotten memory lay there basking. It was the smell of bath salts, pine-scented, that were put in the tub if I had been a good boy.

That then was why I felt so young, as though the world was just beginning, when I stood, single tear on cheek, in front of the great gate of Engakuji. I told my companion.

“How very fascinating,” he said. Then, as he often did, he turned the experience into something of his own. “I often have had experiences like that,” he said. “I am very close to my childhood. Though with me it is cinnamon toast.”

And he brushed back his salt and pepper hair, cut in the loose and boyish fashion then favored by Englishmen of his age—not as old as my sensei but considerably older than I.

This was R. H. Blyth, a friend of Dr. Suzuki’s, whom I had met at Engakuji where he had regarded my efforts on the sofa with a silent but apparent amusement.

“Bath salts, eh? Perhaps you thought that Zen would be a hot bath? More like a cold shower, eh, what? Not that I know much about it.”

And he tossed his head as he usually did when he said this, always thus disassociating himself from the Zen that had appeared in the titles of several of his books. “No, no. Literature. I am all literature. Never knew anything about Zen. Fact is, you know, no one does.”

When I would bring up some Buddhist matter, he would answer with an affectionate scorn, “Oh, that stuff. That’s old Suzuki’s department, scarcely mine. Give me Wordsworth any day.”

Then he would quote something. He was a prodigious quoter, could go on for whole paragraphs, and never apparently make a mistake. Then, “What do you want to study that stuff for anyway?”

I told him that I didn’t study, not really, just listened to Dr. Suzuki.

“Well, that’s better,” he said, as though mollified. Then, “There is nothing the matter with it, you understand. It’s just that it’s not for study.” Then, “Suzuki’s a great talker.” This was presented as fact rather than opinion. We knew what that stuff was worth. It was worth a great deal. It was not worth all that much.

As I listened to Blyth, who was also a great talker, I sat back and appreciated the rationality, the logic. He usually expounded on Wordsworth or Blake or the haiku. And what he said seemed to me attractively vague after the rock-hard incomprehensibilities of Dr. Suzuki. And Blyth’s concept of revelation was quite different from that of my sensei. It was not the result of time and hard work. Wordsworthian revelation could occur just about any time, any place.

“It could occur even in bed. Oh, yes, seriously. Suddenly. In bed.”

Then he regarded me in an owlish manner and I remembered his having told me of a beautiful girl who was apparently a member of his large and attractively disordered household. I smiled, picturing him in a sudden state of satori, and at that moment my eyes opened, my smile faded, and I saw a connection—a real one, a bridge of living tissue between my faltering need for religion, my inclination for whatever I thought Zen was, and something I knew quite well: that inchoate bundle of needs, satisfactions and exhaustions which I called my sex life.

The pines of Ueno had long passed but now their fragrance returned. The bridge was there. Another means of thought had been revealed, and for the first time Zen seemed real to me.

Kannon was again sitting on my lap. I was returning her to Engakuji. The plum blossoms had passed, the cherry blossoms were budding, and it was raining. I had lived with Kannon for more than half a year, had derived comfort, pleasure, and pride—a Hakuin on my humble wall. Then, as is the way with pictures, or as is the way with me, I gradually forgot about it. Now, carefully wrapped, she rested on my knees. Going home.

Once there we sat in the now nostalgic odor of mice. Dr. Suzuki removed the wrapping, and held the picture at arm’s length as though to renew acquaintance. Then back she went on the wall.

I thanked him for everything and he smiled. Then, as though offering a further gift, “Not at all, Mr. Richie. You are, you know, very much of this world, very much of this flesh.”

He then smiled as though the smile were a way of shaking an understanding head at the ways of this world. And he was right about me. I nodded and as I admitted this to myself I understood—a kind of illumination it was—that I had no vocation and never would, not because anything was missing but because I would never summon up the necessary discipline. Not that it was impossible—nothing is impossible—merely that it was very unlikely.

I looked at Kannon, back on the wall and looking at home no matter what wall she was on, and at Dr. Suzuki, always a man in the present tense, and I thought of the slender but sturdy bridge that now connected me to my own reality.

Richie’s billet was the Continental Hotel, originally the main office of Ajinomoto KK until the Occupation moved in. There he roomed with Herschel Webb and Eugene Langston, who became Japanese scholars. For a memoir Richie reworked some of the 1947 journal entries that told how he met them.

summer 1947. I was late for breakfast and all the tables in the basement dining room were taken, so I asked a man reading a book if I could sit with him. He looked up and smiled, but so politely and so briefly that I was not tempted to begin a conversation. Until I saw what he was reading—then we had lots to talk about.

The book was Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood and the reader was named Gene Langston and though only a few years older than I, he had already met the author.

“What was she like?” I wanted to know.

“Well, let me see,” he began—a reasoned response which I soon learned was typical of him. “A bit abrupt, dark, not given to smiling, at least not with me. She was lesbian, of course.”

I marveled. Never had it occurred to me that authors might share attributes with their characters.

“Not that that is either here or there,” he said, a smile already apologizing for an observation which might have been misinterpreted as criticism. He did not criticize, the smile said.

Then, learning that I too had read the book, he became more interested—for it was unlikely that two members of the Allied Occupation of Japan were both reading Nightwood.

He also became more confiding and said that the character he liked best so far was the doctor. All I remembered about the doctor was his saying that what he wanted in life was to cook some good man’s potatoes. But perhaps my new acquaintance had not yet gotten that far in the book. In any event it was too early in our relationship for me to mention it.

Instead, I asked about his work. It was in ATIS, the translation section. Yes, he could read and write Japanese.

Tokyo/Hibiya Crossing, Dai-Ichi Building, 1947. eighth army signal corps

“And speak it too?” I wondered.

“Mo chotto bata o motte kite kudasai,” he politely asked the waiter, requesting that more butter be brought. The waiter, delighted to be spared English, smiled and further pats were produced.

I was impressed. I wanted to be able to speak too and couldn’t. Then he looked at my breakfast and asked how I could eat it. It was the customary contintental fare: gelid egg, frigid toast. Then I saw that his was the only Japanese breakfast in the room: rice with raw egg, miso soup, seaweed squares, and pickled plums. The butter had been thoughtfully ordered for me.

Thereafter, we always breakfasted together. He had read part of Proust, had braved a delinquency report to sneak into a Noh drama, believed that we should democratize the Japanese, and showed a healthy disrespect for authority.

“Shall we go see Jeanette?” he asked over a late breakfast. I was mystified. Jeanette who?

My wonder grew as we walked across to Ginza, past Yurakucho and—just in time—joined the throng in front of the Dai Ichi Building. I knew what was going to happen because the great local sight was neither Ginza nor Fuji, but an important event that occurred twice a day: once at lunchtime, once just before dinner.

An olive drab limousine pulled up to the curb. The MPs guarding the pillared façade directly across the moat from the Imperial Palace, smartly straightened. Snappy salutes were proffered and out from the portal sailed General Douglas MacArthur.

The performance was always the same. In the wings he had put on his famous hat, tilted it at the proper angle, adjusted his profile, and started off, this soldier whom some called with no irony at all “The New Emperor of Japan.”

A number thought so. Today, a country mother held up her child, pointing out the famous sight to the infant’s wondering eyes, an ex-soldier with one leg stood more sharply, and an old man gazed at the pavement in, perhaps, reverence.

And as the famous general sped past and stepped into his sedan, Gene turned to me and said: “There goes Jeanette.”

The mysterious reference was later explained. Singing film-star Jeanette MacDonald, dressed as a page, had, in one of those movies of hers, navigated a staircase in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots, in just such an assured, even pert fashion. Struck by the resemblance between the performances, Gene occasionally came to enjoy it.

“Also,” he said, “you might say it is a kind of penance.” He said this with a smile that was already half a question, a slight invitation to partake, and at the same time indifference if I did not.

I had somewhere read that identity requires the presence of someone by whom one is known—someone who knows who you are, often before you yourself do. Gene observed my enthusiasm, shared some of my dislikes, but always put some distance between himself and these. Though I was beginning to find him a possible model in my relations with this country, he did nothing to encourage me.

He believed in a kind of perfection yet excused everyone from attaining it—except himself. We were talking about The New Yorker, a publication excluded from both commissary and PX after it ran John Hersey’s issue-long account of Hiroshima.

“It never contains a typographical error,” he said.

I, believing in unavoidable sloppiness, said that this was impossible.

“Oh no, it’s not,” he said mildly. “It is quite possible. All that is necessary is that every error is caught. I admire the editor.”

Perfection was possible, all one had to do was to take all possible care. I watched him doing so. When he practiced his calligraphy no mistake was made—the forming of the kanji, the width of the stroke, the pressure of the brush—everything was as it ought to be. Methodical, he built up, line upon line, his ideal world.

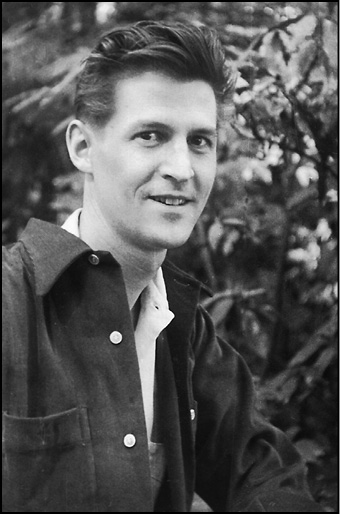

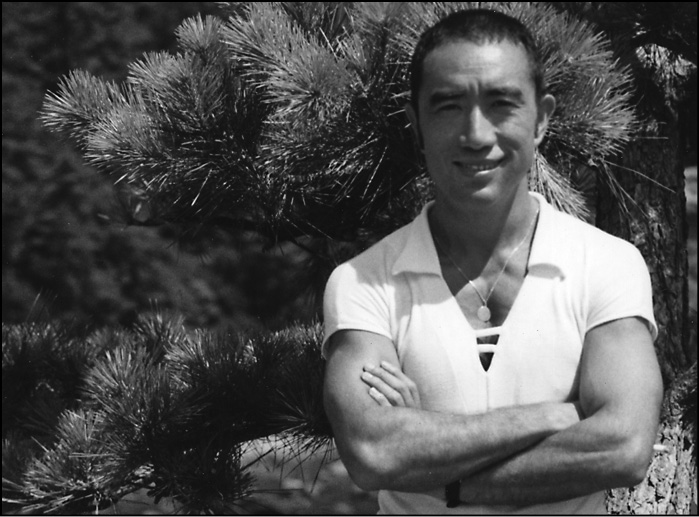

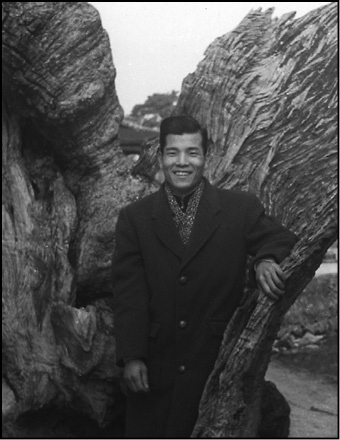

Eugene Langston. donald richie

And yet he was never solemn and could smile at the foibles (Jeanette) he found around him. He was serious without being earnest, and I had never met anyone like him. Yet, he was not a very good model for me. Besides that he would not have wanted to be; he was ascetic, which I certainly wasn’t.

Austere—he was not making a statement with his Japanese breakfasts; he had a liking for the acerbic—he was rigorous with himself and even seemed to enjoy the forbidden. Once when I was dreading our next worming, he said, “Oh, no, think of it as purification.”

“They have a right to live too,” I said, surprising myself.

He gave me a look of deep approval, “So they do, so they do.”

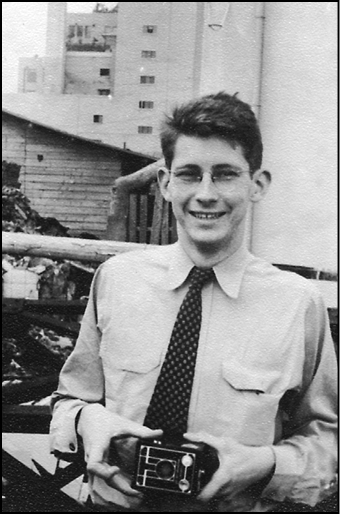

Herschel Webb. donald richie

It was then that I thought of penance and hazarded that the worming might be some sort of atonement. But for what, I wondered. Hiroshima? Jeanette? Being Occupiers? And if so, why? I certainly felt none of the compunctions I sensed in him. Healthily opportunistic, I never questioned a single opportunity and Gene seemed to be questioning them all. He was not, however, usable. I could not model myself on him. But the deeper I knew him the more I admired him.

*

Through Gene I met his roommate. Tall, inquisitive eyes, intelligent nose—this was Herschel Webb. I admired him as well. Even though there still were signs around that sternly mandated “No Fraternization with the Indigenous Personnel,” he had confounded the MPs and gone to the Noh drama.

“I saw Funa Benkei,” he said.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“It means ‘Benkei in the Boat,’ ” and it refers to one of the exploits of the strong bodyguard and friend of the rebel General Yoshitsune, as you will remember.”

I remembered nothing of the sort but Herschel always gave one credit for more learning than one had.

“And now we must have Denwa Benkei,” he continued, not even smiling, and it was some time before I discovered that this means “Benkei on the Telephone.”

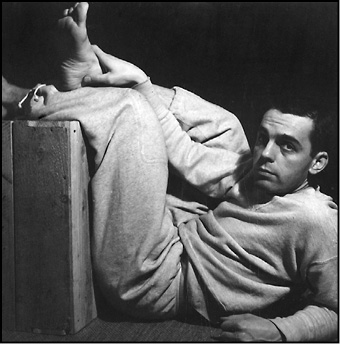

Holloway Brown. donald richie

Herschel could also sing all of Bach’s forty-eight preludes and fugues, managing this through a series of mnemonic aids: “Oh, once there was a crocodile and he was sunning on the Nile.” He could sing opera in English as well. A favorite was from Il Trovatore. It went: “Oh! Oh! They’re burning her at the stake. Oh, how I quake. At the sight.”

Much as I liked him, he was also no model for me. Despite all the fun he was deeply shy. Every day one had to thaw him out before he could begin to respond. Often he helped himself with whiskey. Once thawed he was a delight, but it took time, during which he was polite but reserved, gave short answers if any. When I mentioned this to Gene he nodded and then said that if one wore a lot of armor it took a long time to take it all off.

Sometimes I invited them out for weekends. Across the valley from Engakuji, the temple where Dr. Suzuki lived, was a guest house, empty, which I was told I could use. Square and spartan, it was two rooms, a kitchen, and a view over the Kamakura hills. It had no running water, no gas, and the toilet was an outhouse over a pit. Ideal—so different from the American comforts with which I grew up and which were being imported into the billet where I was presently living.

Trying to boil water for tea over a charcoal hibachi, trying to battle the bees that had taken lodging in the benjo, I felt that I was truly living. Back in Tokyo I was, somehow, merely existing.

We brought food from the PX, and camped out in the two rooms. Gene took at once to its austerity. Like me he believed that the spare was the authentic. When he discovered that the Engakuji library was next door and that he might use it, he was even more contented and would disappear into it for hours.

Noh drama, with Herschel Webb, 1947. eugene langston

Herschel approved of the austere more on aesthetic than on ethical grounds. Also he regretted the absence of ice for the afternoon martini, saying sadly that a warm martini was like a Manhattan with an olive. And, though fearful of the bees in the benjo, and refusing to use it unless absolutely necessary, he admired the view and would sit on the veranda and look at it for hours.

We also amused ourselves in various ways. Once we decided to make a musical comedy out of Le Sacre du Printemps, and put words to the melodies. Those for the opening bassoon solo went: “Oh, baby, see the moon. Oh, baby, see the moon. Way up high, so high. Oh, baby, see the moon.”

Also, using the bedding—sleeved quilts—we put on a Noh drama. Gene was the waki, the character who always explains who he is and where he comes from: “I am an American scholar. I come from near Nihonbashi in Edo.” Herschel was the orchestra, expertly simulating the whistling, pops and groans. I was the shite, the protagonist given to protean change. Most often I was a monster.

We talked about an opera based on Proust. Odette was a mezzo and would have many sforzando markings. Swann would be a typically French tenor: lots of vibrato and a tendency to bleat. A first act aria contained: “O, seul, monotone, all alone by my telephone.”

We also cast a Warner Brothers’ Proust. Odette was, naturally, Bette Davis, and Joseph Cotton was Swann, for want of better. Sydney Greenstreet was, of course, Charlus, but who could Jupien be? “Peter Lorre,” said Herschel with a laugh that soon turned into a cough for he, like Proust, was asthmatic. He used to wheeze on the Ginza and later, after he had become a well-known Japanologist, he could visit the country no longer. “Oh, dear,” he used to say, “I’m allergic to my specialty.”

Evenings, the sun going behind us, flooding the roofs of Engakuji across the valley, we would grill our Spam on the hibachi, boil the wiener cocktail sausages, crunch the Ritz, guzzle the gin, and enjoy the luxury of our Japanese life.

Most of the other pages of this period have been previously used, particularly in Where Are the Victors? and in the unfinished memoir In Between. Here are some excerpts from the latter.

late summer 1947. Wandering in the city after work, smelling camellia hair oil, dusty long unaired kimono, the passing night soil wagon with its patient ox, listening to the incomprehensible murmur of conversation around me, looking into eyes suddenly averted, I try to make sense of what I see.

In a way it already makes sense—Tokyo in ruins still reveals something known from Chicago, New York and, during the war, Naples, Marseilles: the look of a big city just anywhere. In another way, however, I begin to apprehend alternatives to things as I already know them.

The way the buildings stand—those that still do—in relation to each other; the way the rooms—those few I have seen—with their tatami matting, their interior stages for scrolls and flower arrangements, divide space: this is different. The politeness—for so I read it—of people who might not be starving but who clearly do not have enough to eat: this too is unlike. And the acceptance, the shrugs, the smiles, the willingness to continue, to begin again, to look on the bright side of things—I wonder how my hometown would have reacted to a near annihilation.

Another country, I am discovering, is another self. I am regarded as different, and so I become different—two people at once. I am a native of Ohio who really knew only the streets of little Lima, and I am also a foreigner who is coming to know the streets of Tokyo, largest city in the world. Consequently I can compare them, and since comparison is creation, I am able to learn about both.

Already I am as absolved as I will ever be from prejudices of class and caste. I cannot detect them here and no one here can detect them in me, since my foreignness is difference enough. So, I remain in a state of surprise, and this leads to heightened interest and hence perception. Like a child with a puzzle, I am forever putting pieces together and saying: Of course.

Or, naruhodo, since I am trying somehow to learn Japanese. And knowing a language does indeed create a different person since words determine facts. Here, however, I am still an intelligence-impaired person since I cannot communicate and have, like a child or an animal, to intuit from gestures, from intent, from expression.

Language will perhaps eventually free me from such elemental means of communication but at the same time ignorance is teaching me a lesson I would not otherwise have learned. While it is humiliating to ideas of self to be reduced to what one says—nothing at all if one does not know Japanese—it teaches that there are avenues other than speech.

I knew a little about this. In Italy or France during the war, sitting through foreign films without English titles, I did not learn much about the film but I learned a lot about filmmaking. How the director and his writer and cameraman had thought about time and space, the assumptions they had made, the suppositions they had built upon, their apparently unthinking inferences. Now again, in a very different country, I am again beginning to understand the film without comprehending the plot.

I look at the janitor’s closet in the Kokubu Building where I work, see the box for shoes and otherwise the luxury of empty space; peer into the translator’s desk drawer and notice that she has classified differently—all long things are in one place, all round things in another; gaze at the mat-floored room where the ex-president once sat, and perceive the tokonoma, the stage-like space where sat time itself, in the shape of a seasonal scroll and an oft-changed arrangement where the flowers were always fresh and always looked the same—both renewed by an ancient secretary whom the war had left untouched though it had carried the president away. Trying to read things like this is like learning Braille, as though another sense is involved, where sensing becomes something like grammar.

After only a month, I see that I risk ignorance if I remain typing away in what I scornfully call Little America. My job, nine-to-five in an office that could have been anywhere; my home life at the Continental Hotel, all Spam and powdered potatoes and lumpy pillows; my recreations, the PX, a cheap made-in-America bazaar, the allowed entertainments, movies with the GIs and bingo night at the American Club, occasionally special Occupier-night, one performance only, at the Kokusai Gekijo All-Girl Dance Theater—all of this begins to appear more and more unreal to me.

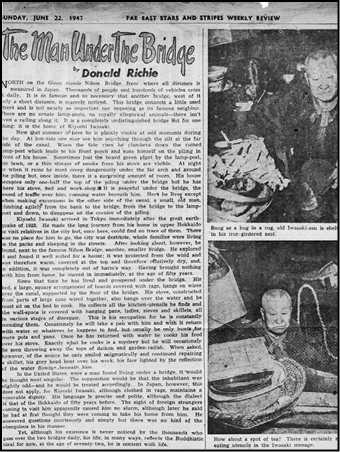

Richie’s first feature in Stars and Stripes, 1947. stars and stripes

Unreal and unpleasant. Little America, try though it does to impart democracy and individualism, is also a territory where the Japanese are worried over, and are made objects of condescension. They are treated like blacks in the American south, or like the “natives” in Forster’s A Passage to India, a work I recently read. Or worse. Our two GI drivers call our janitor a gook. I soon see I will experience nothing, learn nothing if I stay within these commodious and American folds.

Thus when I learn that we, the Occupiers, are regularly wormed, I am somehow pleased. Back in Ohio worming was for animals or what we still called “poor white trash.” Here, however, our salads are cultivated with something called “night soil,” a fertilizer composed of the excrement of the Occupied. We consequently get whatever they have.

This is indeed an Occupation—our American bowels a nurturing home to native Japanese fauna. No matter our own sense of superiority, our manifest efforts to recreate our own civilization in these far islands, we are every three months reminded that we are merely human after all. This we ascertain by glancing into the bowl and then hurriedly flushing it. Going to the toilet after having taken worm medicine is a great leveler.

While never looking forward to the doses, I welcome the effect. Not only am I then worm-free for another three months, but also I am sharing something with the Occupied. In a situation where our people call their people gooks and where we are forbidden to make their social acquaintance, where they are held to be morally as well as socially inferior to us and are thus in need of purging, their worms seem positively friendly.

I look about the office of the Allied Cultural Property Division where I work. Stay I must in body, since I am here to work, but SCAP has little control over my ambitions. Therefore I long to fraternize with the forbidden indigenous personnel. Indeed such aggressive and self-conscious segregation—Japanese and Americans, Occupied and Occupiers, Them and Us, Gooks and Gentry—make me want to flout such authority. Abrogating arrogant and useless rules is attractive in itself, but a further reason is that these orders are the glass against which I press my longing face, no less than do the Japanese when, alien in their own country, they gaze packed and flat-faced at solitary me in my Allied-Only car on the Tokyo trains.

*

The offices of the Allied Cultural Property Division have a weekly mimeographed bulletin and I know the person who compiles it. She tells me they are looking for “human-interest” material and I decide to fill this need. Having read Nitobe Inazo on Bushido, Ruth Benedict on toilet training, R. H. Blyth on the haiku, I now want to write something myself.

I have the means. I can type—indeed, I have often thought that I became a writer simply because I know how to typewrite. First comes technique, then style; no typing prowess and I would have turned into something else. My problem in Japan is where to begin—there is too much to write about. But here, however, was something specific—human-interest.

I find some. Just upstream from our building just off Nihonbashi is this other bridge, smaller and so far as I know, nameless. A man lives under it, among the girders. Having moved in after the war, he there remains. Grizzled, he is often seen perched in his watery home. So I go to see him, taking with me the unwilling office interpreter.

She had said we would be bothering him. No, I said, we would be interviewing him, trying to make it sound as though this would be no bother. He is a poor man, she had said. We couldn’t pay him, I said, but we could give him something—maybe Spam, or cigarettes.

Cigarettes, she said, so we set out with pencil, pad, and a carton of Camels.

Our host, Iwasaki Kiyoshi, is appreciative of the cigarettes and loquacious in return. Shortly, our newsletter carries: “Man Under a Bridge—The Story of a Refugee from Ruin.” This refugee “though clothed in rags, maintained a venerable dignity,” as he told his uncomplicated story. “He answered questions courteously and simply but there was no hint of the obsequious in his manner.”

There was plenty in mine. I had written about the amenities of his dwelling using such phrases from far Ohio as “snug as a bug in a rug,” and observed that “the sight of the foreigner coming to visit apparently caused no alarm, though later he said he had at first thought that we were coming to take his home from him.”

My completed work excites some interest among the office staff—this kind of “coverage” is still rare. Some think the Japanese still somehow enemies. My kind of condescension is new. Consequently, it also attracts the notice of the feature desk of the Pacific Stars and Stripes, the Occupation newspaper. Summoned thither I am told by the editor that he guesses I have gotten myself a new job. I have, he says, the human touch.

This I much doubt, and even if I do have it, do not believe that my GI readers will be interested. Nonetheless, I am assured that my piece has human-interest and that human-interest fits in with the major aims of a democratic press. As such my man under the bridge qualifies and, consequently, so do I.

Eighth Army photographers are sent to capture Mr. Iwasaki in his watery lair and a rewritten version of my article becomes a cover story in the Stars and Stripes Weekly where it again excites some mild interest.

A year before it would have excited none—lots of people were living under bridges. But now they are few, there is creeping fraternization, and the Occupying stance is relaxing. The days of Japs and Gooks are numbered. We are now living with a fellow race. I have, despite or because of my patronization, indicated this. The newspaper authorizes my transfer, my grade is moved a step up, and I am feature writer and film reviewer.

Feeling guilty at having gotten so much from this penniless person, I take further cigarettes as well as a fifth of Four Roses to my benefactor under the bridge. He is, however, no longer there. My article has alerted the Japanese police, who have swiftly removed this unwelcome relic from the old days.

Having ruined the life of an affable old man, I find myself haunted by his ghost. In my new office at Stars and Stripes comes the shout: “Get Richie to do it. He’s good at human-interest.”

*

I, strangely, did not regard movies as human-interest stories. Perhaps because, as for so many of my generation—those who, like me, had profitably spent their youth in the dark—films had become sacerdotal, something so out-of-body that they were no longer quite human.

For me, as for so many, the movies were a preferable form of life. I knew nothing about films themselves—did not know how they were made, or why. And if I knew next to nothing about the movies of my own country, I knew nothing at all about Japanese films: did not understand the language, recognized neither stars nor directors, and knew little about Japan itself. From such beginnings knowledge of the Japanese cinema could only grow.

Though I was supposed to merely endure the latest Hollywood product in the comfort of the Signal Corps screening room, I defined my mission as otherwise. Coat collar turned up, eyes alert for the marauding MP, I bravely sneaked into Japanese motion pictures theaters all over the city, where I was forever getting sisters confused with wives and mistresses with mothers, and becoming lost in the labyrinths of the period film.

Dumbly I absorbed reel after reel, sitting in the summer heat of the Nikkatsu or the winter cold of the Hibiya Gekijo. Yet, in these uncomprehending viewings of one opaque picture after another, I was being aided by my ignorance. Undistracted by dialogue, undisturbed by story, I was able to attend to the intentions of the director, to notice his assumptions and to observe how he contrived his effects.

Though I understood little about cinema, I had seen a lot of it, and now I began to realize that space was used differently in Japanese films. There was a careful flatness, a reliance upon two dimensions which I knew from Japanese woodblock prints. And emptiness, I had already guessed, was distributed differently. Compositions seemed bottom-heavy, but then I realized that—as in the hanging scrolls I had seen—the empty space was there to define what was below: it had its own weight.

And there were also many fewer close-ups than I was accustomed to in American films. The camera seemed always further away from the actors—as though to show the space in between. A character was to be explained in long shot, his environment speaking for him. Sometimes I could not even make out his face, but I knew who he was by what surrounded him.

I also noticed the pace of the films of the period: slow, very slow. Time, lots of it—long scenes, long sequences—was necessary. Feelings flowed and flowered to what Ohio would have thought extravagant lengths. The screen was awash with undammed emotion. Yet, though allergic to the displays of Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, I somehow did not mind the emotionality of women I later discovered to be Tanaka Kinuyo and Takamine Hideko.

Wondering why I so willingly wept along with them, I decided that the very fact that they were so far away, and crying for such a long time, compelled my moving nearer, and hence feeling more. So different from the big and demanding close-ups of Joan and Bette, their nostrils large enough to drive trucks into. Being apparently asked for nothing I gave more. And so, sitting there, smelling the rice sweat and the camellia pomade, I was learning my early lessons in Japanese art.

I wonder which films taught me. 1947—one could have been Ozu Yasujiro’s Record of a Tenement Gentleman, released that May; another could have been Mizoguchi’s The Loves of Sumako (with Tanaka Kinuyo), released that August. Whatever I saw, I have forgotten, if I ever knew. I later looked at both the Ozu and the Mizoguchi but not a memory budged. The first Japanese film scene that I could identify was one I recognized only because I had watched it being made.

*

I was taken to the Toho Studios not because of my new critical position, but because I had met with the composer Hayasaka Fumio. He was a pale, spectacled man who having heard that I had some recordings of new music, wanted to meet me. Regulations on fraternization with the indigenous personnel having been relaxed, I could ask him to my billet, and escort him up in the front elevator. In my room we heard the Berg Violin Concerto, newly recorded and inexplicably on sale in the PX. He sat silent, lost in the music, and when the Bach chorale appeared his eyes filled with tears.

Hayasaka responded by inviting me to Toho to watch being filmed a movie for which he was doing the score. Setting out early to avoid the MPs, late risers all, we stood bouncing in the suburban train as it bumped and rattled through the new, raw countryside west of Tokyo.

The Toho Studios, large white barns, were in the midst of muddy paddies. Inside, the big, muffled prewar camera clunked by on metal rails and the mike was held aloft on a bamboo pole. Both of these were aimed at a carefully ruined set of buildings, meticulously constructed, every brick out of place, in back a dirty gray cyclorama with miniature ruins on the nearby horizon.

A whole blasted neighborhood had been built around a scummy-surfaced sump on the banks of which were a few new plywood buildings, their fronts festooned with neon. In the sump itself floated carefully placed garbage, a single shoe, a cardboard box, and a child’s lost doll. Yet what I was seeing was no different from what I had seen on my way there.

Ono Tadamaro performing Bugaku. stars and stripes

It had not occurred to me that film heightened reality. I had always thought of it as an alternate. Yet this—though different from Johnny Weissmuller’s lost city or from Norma Shearer’s Versailles—was still a movie set. Obviously so, yet, huge on the black and silver screen, it would look real.

There was the camera, there was the mike, and there were banks of lights. And there was the director, wearing a white floppy hat; there was someone I guessed was the star. He, in a loose Hawaii-shirt, a young actor with slicked back hair, was practicing menacing an older man with a beard and round-rimmed glasses.

The young man was supposed to walk along the sump toward the older man. This short scene was taken several times very swiftly, no stopping, apparently, for consideration. I wondered at the speed with which this reality was captured, having always thought that making films took an enormous amount of time.

And the noise. Shouting and clattering, things dropped. I had thought of the film studio as a kind of cathedral, filled with a hushed and reverent silence as the great arcs illuminated a famous profile. Instead, cacophony as one scene was finished and another was begun. It had never occurred to me before that movies were actually made.

For each of the walking scenes the doll in the sump had been repositioned. Now it sank. The director smiled, shook his head, waved his hand, and signaled for a break. Seeing Hayasaka he came over and I was introduced. Then the two actors came and I met them too. I could not speak Japanese and Hayasaka often mumbled, so I caught no names.

Later, Richie has elsewhere said, the composer took him to the Toho screening room to see the finished picture and he learned that the young man in the shirt was Mifune Toshiro; the man with the beard was Shimura Takeshi; the man in the floppy hat was Kurosawa Akira, and the film was Drunken Angel. Whenever he now sees this film and that sequence by the sump comes on, he looks to the right of the screen: “There I am, just a few feet off the edge, twenty-four years-old, watching a movie being made.” Otherwise, from the period 1947 to 1949 the only journals remaining in their original state are those below. The first of these appears in a different version in The Donald Richie Reader.

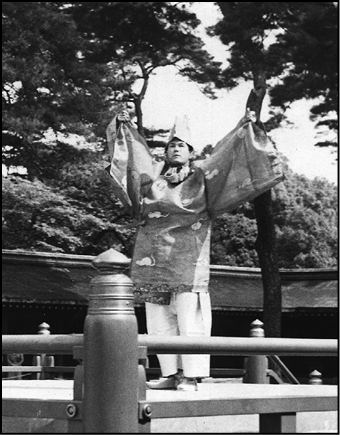

16 october 1948. This afternoon Meredith [Weatherby] and I went to a performance of Bugaku in Ueno Park. And this afternoon, watching Ono [Tadamaro] again dance, I felt that he had come to contain for me the beauty, grace, and dedication of Japan—as though he were an emblem of his country.

Meredith and I entered the small park behind the museum and came upon the small tent where the performers were already putting on their costumes, where the orchestra was already tuning or warming their instruments. I thought of the Heian period recaptured: the costumes of antiquity, the different flavor of everything Japanese. We passed the tent (for we could not stop and stare, so conscious were we of being foreigners—which attitude we conscientiously cultivated so as to be differentiated from other of our countrymen here); passed four little boys dressed in costumes of the eighth century court, with wings and little tails attached to them; passed the musicians already arranging their brocade and the dancers still taking off their street clothes; till we reached the red square lacquer platform with its copper railing and, before it, the empty seats for the audience.

Invitations apparently were given only to higher officers. Consular representatives were here, and Meredith saw many acquaintances. [Weatherby was at this time in the consular service. Later he was to create and head the publishing firm John Weatherhill, Inc.] The various missions were here as well, as were the more socially prominent in the Occupation. We were told that today was the elite party and tomorrow the plebeian. I had had no invitation at all to this one but found my press card acceptable.

Just before the musicians arrived Prince Takamatsu appeared—a tall thin man with a large nose and dark eyes. He never missed a social engagement—indeed, was probably not allowed to. Princess Takamatsu was less in the background than usual, wearing a pretty kimono and a smile, and they were soon surrounded by Allied friends.

Then the music began. “Celestial” is the word I always think of, and so it is since it does not seem of this world. The sound of the sho, that frail, dissonant noise floating into attending trees, disappearing into the clear blue sky; the curious double time, the apparently accidental syncopations, the stately stance of the music—surely this is celestial.

The dancing—maybe that is what makes the music celestial; the simple opening prelude, unchanged for a thousand years: the dancer with halberd, walking forward to kneel, then the slow turning of the head to the right until the profile shows against the sky, and the unexpected, mechanical quick movement which brings the profile to the left.

Ono appeared only in the last dance, a famous one I’d seen once before, in which four men performed in the costumes of the eighth century, covered with brocades and stiff gauzes, hats of lacquered wire, halberds of lacquered wood, only their heads and hands visible. As each of the four entered the platform from among the trees and emerged into the sun, the same choreographic formula was repeated, like a fugue or, more exactly, a four-part canon, repeating each other’s movements, a movement behind.

All four stood, each at a corner of the platform, and then began the dance—a war dance in which a stylized battle takes place. The two on the left precisely imitate those on the right. Swords are therefore held both toward and away from you at the same time and all movements are identical. The most beautiful moment comes when, the accompaniment of the music reaching that curious double beat, the dancers begin slowly moving around the inside of the square, each occupying, within two beats, the place left vacant by the man before him. The movement, the deliberate raising of the leg and bending of the foot and knee, the squat with hands on thighs as the dancers change position, the curious up and down motions as they bend their toes in their rounded lacquer boots. The prescribed, ritualistic movements of the hands, all in exact accord with the other. The studied expressionless faces and blank dark eyes which so ignore the three other dancers. The movements are like beautiful human machinery and the music soars to the sky.

The dance is finished and the dancers depart: all four describing a figure—one steps down, leaves three, steps down, leaves two, and finally Ono alone describes the figure. His back is to the audience but I still see his face. For, in this hour, he has embodied all that Japan holds for me.

Later I have Meredith take me to the tent, now shorn of its Heian associations: it is simply a garden tent where Japanese are replacing Western clothes, tying shoes, fixing worn neckties and putting back on black horn-rimmed spectacles. Ono is introduced to me. He is wearing a coat too small for him, a clean but worn white shirt, a dark necktie. In his lapel is one of the tiny red feathers which mean the wearer has contributed to the current Community Chest drive. He smiles, bows and then shakes hands.

Am I disappointed? Oh, no. How could I be disappointed with the Heian period? Meredith later said that Ono is not particularly attractive—and I suppose he’s not. Without his costume he becomes ordinary and on the street I shouldn’t notice him. But I have seen him wearing stiffened gauzes and salmon brocades, and I have seen his head surmounted with lacquered wire and the feathers from birds that ceased to live a thousand years ago. I have seen Japan in him.

17 october 1948. Like so many of these autumn days, this one began in clouds and damp mists and, looking from the window at six this morning, it seemed the day would not be fit for picture-taking.

Later in the morning Al [Raynor, a friend in the same billet] and I went to Kanda to buy books. This was arranged, put off, rearranged, and again scheduled several times before we actually left. The reason for this was Al. Originally he had wanted to go into the country today, for he revels in great open spaces and likes to shake from his heels not only the dust of the city, but also every place where he is acquainted and knows his way about. He often says he would be perfectly content traveling always, but I doubt it. He is too fond of study (his translation of a Noh we have been polishing these last two weeks) and too fond of comfort too (his attachment to his room and habitual three helpings at meals) to ever be more than mildly fond of the movable life.

This morning he was looking for Noh books and I was looking for the one on masques that I saw last summer and have been looking for ever since. I didn’t find it but did buy a 1922 number of Broom with half of Claudel’s Protée translated in it, and the Sacheveral Sitwell book on southern baroque art I’d been wanting for some time. Also I got several copies of this month’s Europa that has my article on Gide in it. While at the magazine stand I noticed a young student reading it and longed to declare myself the author. Also found an early Shakespeare Company edition of Ulysses, only the price was over two thousand yen and the proprietor knew its value. Al found a Noh picture book that pleased him.

It was now time to go again to the Bugaku. Al suddenly said he would rather go out in the country and was already regretting he had spent the time in Kanda. I began feeling sorry for myself, wondering what I should do if he wouldn’t go; he doubtless feeling I was using him—as I was naturally—and resenting the fact that he wasn’t out in the country. We drove for a long time in silence. He broke it once to ask me to stand up: we were going fast and I like to stand up in the roofless jeep when traveling fast, but I refused and he said no more for a time.

The silence continued and was then rent by his flatly stating in a tone of exclamation that he was going to the Bugaku and that we were going to stay all the way through, too—just as though I’d been disagreeing with him.

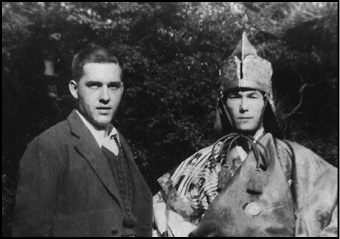

The crowd was much grander this afternoon, much smaller. When we arrived, about half an hour before the performance, the little tent was surrounded by Americans. Cameras were everywhere, from box cameras to big German models, from hand-wound motion picture cameras to large and expensive tripod battery-run affairs.

Ono appeared, this time in full costume, looking again like living Japanese history. He was polite, talked some with Al about the dance and then asked where we wanted to take the pictures. I drew him away from the crowd and posed him in the sunlight. Then, ashamed at being among the snappers, I took several pictures and had Al take my picture with him. Again, through Al, I asked Ono to visit me, and he, through Al, said that he would be pleased to. I told him that I would let him know the time and date. Exactly why I did that—why I invited him—I don’t know but I knew I didn’t want to lose what I had captured.

18 october 1948. In the afternoon I willfully stay in the [Stars and Stripes] office working over a synopsis of the vampire cat of Urashima for the paper. In the evening—while Holloway [Brown, his current roommate] entertains a Mr. Gunji and his younger brother—the elder Gunji absurdly good looking, noisy, and as American as possible, while the younger Gunji, not at all good looking, is reserved to the point of being incomprehensible—I work with Al, editing his translation of Sumidagawa. I don’t like the lines:

By the shores of Horie High above the busy boatmenAlways crying, always cryingAre seen miyako-dori.

I recite this Longfellow-like to the tune of Hiawatha, which irritates the translator. He likes his original, arguing that, after all, it is a quoted poem. I, in turn, state that no Japanese poem ever sounded like that. After half an hour of wrangling we straighten it out; but now, neither is satisfied.

By the shores of HoriegawaAlways crying as they flyHigh above the busy boatmenAre seen miyako-dori.

Any translation from Japanese to English, certainly including my neglected Asakusa Kurenaidan, [the Kawabata novel] contains the difficulty of connotation. Every Japanese knows that miyako-dori are seagulls and are mentioned in a famous poem by Inahara, and are called the capital bird because they are, for some reason, never seen in the old capital. You can’t say that in English and if you do the book is mostly footnotes. Al feels this is such a difficult point that we get no further on the subject.

19 october 1948. Sho [Kajima Shozo] in to see me this morning, wanting nothing in particular, just to talk. Small, eyes so big they look round, he is the only Japanese I have met whose English is so good that we can carry on conversations about things that matter to us. Particularly matter to him. Anything foreign, as though he has been starved for so long that he cannot get enough.

Now we discuss the possibilities of translating Camus into Japanese, and how the intellectuals here now shun Sartre. Sho blames it on Life magazine, just now discovering existentialism and hence degrading its current reputation in Japan.

With Ono Tadamaro. meredith weatherby