25 february 1990. Lunch and dinner with Sarah [Gilles]. She has been working by day for Vogue and with the [Rolling] Stones at night. Mick [Jagger] wears a scarf around his lower face when outside. A cold? No, no. So long as one doesn’t see the mouth he is not recognizable. Also, ah, these working class boys, so refreshing. Mick fucks anything standing still. Does this happen to Sarah? I wonder, then decide no because she is one of them, one of the boys. Not interested in girls, however, her own boyfriend probably squirreled away somewhere; she is a member of this late-twentieth-century version of Our Gang.

Interested in abstract fucking, I tell her how Paul Getty’s then-wife led me to the top of the Moroccan palace and opened the grille, and we looked down on what she identified as Mick’s bare bum as he pumped away at someone whom I later recognized by her hair ribbon. Inspired, Sarah and I decide to go to the fabled DX Gekijo.

What a disappointment. It has been completely redone. Now the girls merely come out and do their dance, then their dildos, then each other, and finally clean the patrons’ hands with towelettes, and then loll and let themselves be fondled, during which they talk.

Imagine these sex goddesses—for so they once appeared—now descending and showing bad teeth in the guttural accents of Gunma. There was also a new and most unwelcome type—the hoyden. She did an eccentric naked dance, with splits, then came back and had a talk show. Also carried a small rubber hammer with which to hit playfully the heads of those customers who were rubbing her too hard or in the wrong direction.

The old air of mystery, of primitive religion, the innocent spectacle of customers shedding trousers and engaging in the sacred act of love—all this is gone. Customers no longer climb up. Instead, they stick in a finger or two and are admonished with rubber hammers. The worst is that the image of the goddess is gone. That of the kindergarten teacher, the indulgent mother, never far away, is now brazenly laid bare.

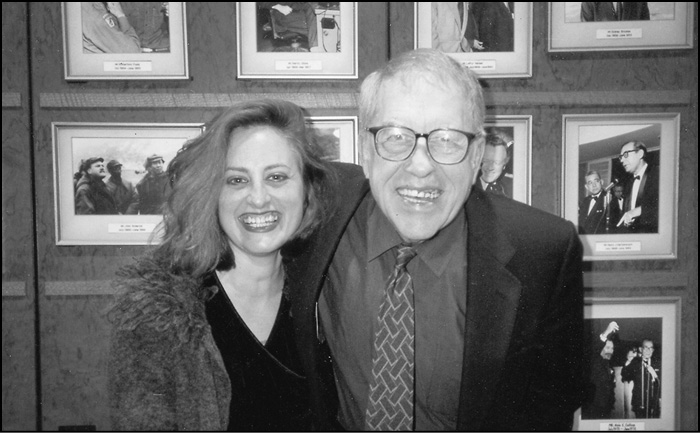

With Kurosawa Akira. kawakita zaidan

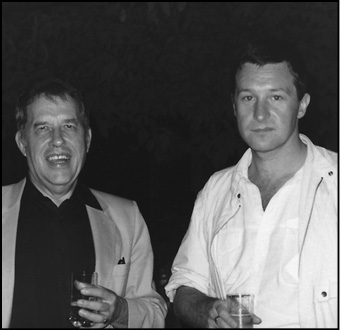

With Oshima Nagisa. kawakita zaidan

There is also a nasty undercurrent. In the front row are some Chinese—tourists or students or workers. Not much Japanese was spoken among them. Ms. Hoyden made a lot of this. Sly insults in the tongue her guests do not know. Undercover snickering from the audience. Man next to me, jovially, “Oh, these Chinese. They just don’t understand.” Don’t understand what? asks the suspicious foreigner. “Well, our ways, we Japanese.” Even when currying cunt, it is still we Japanese against all.

However, Ms. Hoyden got her comeuppance. Flushed with her success she took on Sarah. “Oh, I want that lovely white lady to take a picture of my pussy,” she said, brandishing her Polaroid. I said no. She turned on me, “Even though you speak Japanese and all, you got to let the lady speak for herself. Nice little white lady.” “Nice little white lady is not lesbian,” I crisply averred. Loud laughter from the crowd, pouts from hoyden.

Then her big mistake: she harangued the crowd. Accused us of being stingy in not taking picture of pussy (five hundred yen the crack), and did so with no placating humor. Crowd grew cool, cold, and then sullen. Too late she sensed the turn against her. Beating a naked retreat she one last time turned to face us. “Why don’t you just all go home.” Ironic applause. I had to apologize to Sarah. Yet another aspect of old Japan vanished.

1 may 1990. In the evening at the U.S. Ambassador’s residence, the reception for Martha Graham. She is ninety-six now, and we had expected her to be wheeled in like the cake, but the Armacosts always do things well: There she was, in another room, enthroned on a teak chair, and we were allowed in several at a time, like pilgrims.

She looked very Chinese—perhaps the chair suggested that. But Ming—late Ming. Her hair was pulled back tightly and she wore jewelry, like the idol she was. And, she looked lacquered, a living effigy. Cordial, smiling occasionally, and then, often, that terrible lost look that very old people have, like an aged child who has forgot its way. Then a graceful and unselfconscious recovery, and she was nodding and smiling. Then again, that awful lost gaze.

I heard the press conference was like that. Periods of lucidity, periods of blankness. Talk with an acquaintance about Copland, nearly that age himself now and even worse off. Some days there, some not; some days remembers everything, some days nothing. Not Alzheimer’s—that rarely permits these merciless retreats to sanity. No, just old age, and the dimming of the brain.

And I first saw them both when they were half this age. New York, the forties. Appalachian Spring. She had danced and he was in the audience. Smiling, bowing, hand in hand, the two of them. I did not know Aaron then, but I still remember him best smiling from the stage.

The notables lined up. A few of the American ladies attempt a curtsy. I did not join the line. The ambassador gave a speech. “Martha Graham: if America had a living national treasure, she would be it.” Yes, that is what she would be, staring straight ahead, stiff in her chair, her jade earrings barely moving—a living national treasure.

23 may 1990. Party for Kurosawa—eighty now and just returned from the Cannes festival. Prolonged applause upon his smiling entrance. Like royalty. But then he has always been tenno [emperor]. The difference is only in the new affability. This is stressed in the various speeches. Fat old Yodogawa Nagaharu, TV film fan, kept exclaiming, “And there I was back in the old days, I wrote all the ads for Sugata Sanshiro; so maybe thanks to me, Kurosawa is what he is today, ha-ha. But seriously now, what I want to remark upon is the difference. . . .”

A great difference. In many ways. Kurosawa, who so rightly scorned the Japan Academy Awards for years, now takes money from Lucas and lets Dreams be “presented by” Spielberg, now goes to the Hollywood Academy Awards, now allows Warner’s send him to Cannes. However, such thoughts as these do not intrude. Instead, Oshima makes an emotional speech and says, “Thank you, thank you, Mr. Kurosawa,” he who only a decade ago was saying coldly that Kurosawa was what was the matter with Japanese cinema. Best speech was Ryu Chishu’s. He must be near ninety. He stood there, now much older than when he impersonated himself in Tokyo Story, and said, “I don’t really know what to say. Congratulations anyway. I’ll step down now. Thanks anyway.”

24 may 1990. In the park, stopped to talk to the resident prostitute. Pageboy, sensible shoes. When in spirits, given to wisecracks. “Haro daringu,” in English. Followed in Japanese by, “Real empty tonight. I only did two.” “But that is good, isn’t it?” I ask. Shake of the pageboy, one hand reassuring the breasts. “Good? No, three or four is average.” “What was the most?” “Ten!” “Ten in one night?” “Between the hours of 7 and 11. Ten!” “You were busy.” “I was just flying around.” Laughter. Then, “Not so hot tonight. One in the bushes, one in the ladies’ john. No sense taking that kind to a nice hotel.”

I decided to ask something I had been curious about. “Do they know? Your customers?” “About half and half,” was the candid reply. “Those that don’t always get excited and feel my tits. Those that know half the time want to suck my cock or get fucked. You’d be surprised. Last week the straightest, butchest, gang-boy type you ever saw. Muscles, tattoos. And we get in the bushes and he drops his pants and bends over. Wanted it up the ass.” “Did you oblige?” “Sure—he couldn’t help it, probably got used to it in prison.”

“Do you ever mix the two and try to fuck the one that thinks you’re a lady?” Laughter, then, “All the time, all the time. It’s a problem.” Seeing I was ready for further details, “I don’t get fucked you know, too dangerous, and I don’t suck cock either.” “What do you do then?” I wondered, thinking this a singularly untalented male prostitute.

In answer he swung his handbag and said, “Want to see my cunt?” I said I did, and he produced an object made of rubber. Then he demonstrated, hiked up his skirt, put it between his panty-hosed legs. “Feels just like a cunt,” he said. “And I’m quick about it, have it right down there in no time. They never know.” “It doesn’t look much like a cunt,” I said. “Not supposed to. No one ever sees it. No, no don’t touch it, it’s still full of cum from those two guys.” “Don’t you wash it out?” I asked. “No, that would ruin it. They would know it was rubber. But with all the cum squashing round inside it feels like cunt. They think they got me all wet, think they got me excited, big ego trip.” “Big trip to the hospital,” I say, “What if the first guy is sick, then the second dips his cock in all that gunk and he gets sick, too?”

“No, no,” he said, “I am OK, I never get sick.” “I’m not talking about you, I’m talking about your customers.” “AIDS, huh?” “Yes, something like that.” “Well, I just don’t know,” he said. “If I wash it they’ll catch on. But once it is nice and squishy. . . .” “I just mentioned it,” I said, “as a matter of possible interest to the health department.”

Laughter, then, seriously, “In Japan, it’s only the rich people who have AIDS; they never come down here to Ueno. You got to have money to go abroad and catch it.” We talked for a bit more, and then he saw a likely businessman, portly, interested. Eventually they walked into the darkness, she with her dirty cunt secure in her handbag.

5 june 1990. To dinner with Louis Harris of polling fame. Taking my advice in New York, he came and talked with Tsutsumi Seiji of department store fame, hoping to get funding for Jimmy Merrill’s movie. It was at Jimmy’s place in New York that I first thought of this avenue. And Lou, with his customary directness, picked up the idea at once and came brandishing it. Seiji had meant to give him twenty minutes and, probably, the time of day. Instead, he sat, stunned in his own office, while Lou outlined.

Harris is extraordinary. I have never met anyone so completely certain. There is none of that doubt of self that one so finds, particularly, in Americans, especially in New York. And even those gestures in that direction (“at least, that is what I think” etc.) are merely social.

His wife sits by, stunned not by him, but by jet lag. “I’m sleepy all the time.” Not him. I cannot imagine him sleepy. Right now he only sips Chinese dumpling soup. “They have ruined my digestion,” he says, speaking of the Japanese and the schedule arranged for him. But one does not believe it. Nothing will ever ruin any single part of him.

Napoleon must have been like this. So utterly sure, so completely certain, that he carried all before him. Seiji must have been overcome. It is not the charm, which is considerable, but the certainty. So rare, so valuable, so irresistible in our rationalized times.

6 june 1990. Evening, explaining Ueno and low life in general to a foreign film producer who has asked for a few lessons. Having told him where to go and watched him enter, I fell into the hands of a hentai fufu. The male half moved into the dark near the pond, then, making sure I was looking, lifted his companion’s skirt like a stage curtain, to show me she had no panties, nor had she shaved. Then he dragged out his equipment and she descended upon him, looking me straight in the eye the while. I do not know what I was supposed to make of this, but realized that I was an object, a third party, a witness. So I smiled and she smiled back, difficult though that was. Then I stretched forth a hand to assist her. Instantly he was buckled up again, and with a “time to move on, time to move on,” he shepherded her around the shores of the pond, she looking back (longingly I thought) from time to time. This is what they do, pairs like this—inflame innocents like myself, then “move on” when things look promising. That is why they are called hentai fufu, “a perverted pair.”

8 june 1990. Spent the morning writing about the burakumin (reviewing Hashi ga Nai Kawa), the proscribed caste, even now in this bigoted land; its creation yet another ploy to control the lives of the citizenry that continues to this day. Perhaps continues now even stronger, in that the citizenry has been persuaded to surrender itself, to exercise self-criticism, to implant the watchful eye within the bosom.

Lunch with Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, anthropologist and also something of an expert on the burakumin, since her book, Monkey as Mirror, connects all these strands of historical Japan. She tells me that the publisher of the proposed translation said he would love to do it but with all these burakumin references he really couldn’t. Now if she could just take them all out. . . . I tell her that when my Inland Sea was translated the publishers (TBS-Brittanica) cut out all references not only to burakumin, but also to lepers.

She left Japan early, opened her eyes, and has never again shut them. “And you?” she asks. “You are me in reverse. How does it come about? How does it continue?” It continues, of course, because I am not Japanese and hence not subject to any of these insular customs. I am not expected to conform, indeed am encouraged not to. “I would not stay here, not even for five minutes, if I were Japanese,” I tell her. “But I am not. And that is all the difference. Plus, that I am a chronic non-joiner and early burst into tears at the prospect of the Boy Scouts.” She nods. She understands.

9 june 1990. With Jonathan Rauch, whom I take out to an Edo dinner and then to assorted glimpses of Ueno low life. He says, and I agree, that revisionism (let alone “Japan-bashing”) is not the proper term for what is occurring. It is simply that a group of journalistic scholars are describing Japan for the first time. And, I say, doing so for the first time without reference to the Japanese model.

It is amazing that for so many years, so many scholars (Reischauer among them) have accepted the Japanese Version. I never have, and I have always tried to accurately describe the place. But I simply did (and do) not know enough—as much, for example, as Karel van Wolferen knows.

Jonathan, so young, so bright, says that he has yet to meet a Japanese any different from anyone where he came from—Phoenix. The institutions are peculiar, but then all institutions are peculiar. The explorer finding Japan “different” is, in a way, merely discovering the last standing wall of the once-imposing Nihonjinron edifice.

30 june 1990. A Beethoven quartet a day. First I read d’Indy, and then Kerman. Then I listen to the quartet, with the score. Then I read Kerman again. So far I am most interested in Opus 95. In particular those two breathless chords, like some deathbed statement reconsidered.

Out at night enjoying the national mix. All sorts of different people. Homogeneous Japan—those who think they are homogeneous—feels threatened. On the bus coming back home there was a feisty little man with a toothpick and a domineering way with his wife. She was ordered to sit down, and then, himself standing, he looked around the bus. There was me and a Pakistani (probably), and two Filipinas, and perhaps a Chinese. And he turned to her and said in a loud voice, secure in his presumed insularity, “Nothing but damn foreigners these days.” (Saikin ya na, gaijin bakkashi da.) I looked up from my Kerman and transfixed him with my alien and basilisk eye. He understood at once that he had been understood. He looked away. Then when the bus went around a corner, stole a glance. Horrors, the gaijin was still regarding him with a mute but ominous stare. He shifted his position, turned his back, snapped at his wife. When I got off the bus, I was pleased to see that he had chewed his toothpick into a pulp. Stress.

1 july 1990. Reading the short short stories of Colette, those that are all bunched together in the middle of the collected volume. I much admire this short-short form. These little netsuke are hard to carve, but worth it. Good for Colette too. When she gets long she often becomes winsome or jocular. She is best (as is everyone) when she is all bone and sinew. This short-short form saves the author from that authorial pose which, as I get older and older, makes me more and more sick. That ghastly attitude of looking on genially, smiling at a suffering world, the master puppeteer. Thackeray has it, James has it, even my worldly and discreet Colette at times. But not in these glorious stories. They make me want to write some myself.

2 july 1990. Busy day. Noon lecture, two hours, on Japanese culture for a group of adult academics from U.S.A.; proofing Kenneth Pyle’s new article for the International House of Japan Bulletin; rewriting the library notes; then moderating Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney’s talk on Tampopo.

Then I came home and found in my mailbox “The Best Radio Plays of Paul Rhymer,” that is, the best of Vic and Sade, the radio program that so delighted my childhood, which so formed me.

One of the joys of Vic and Sade was to stand to one side and learn to observe. Not criticize, observe. And to understand, and to accept. All of this was painless, of course. I thought they were “funny.” And so they are, but they had the transcendental humor shared by Jane Austen and Ozu.

Made of very little, a handful of characters (usually three) in themselves a unit (family), in one setting (house), and this minimal means permitted the depths of fellow feeling which this series occasioned. I never wanted to meet Vic or Sade or Rush. At the same time they were not “examples.” Rather, it was through them that great truths were viewed—beauty became truth.

In bed I read and read. Rhymer’s dialogue is as crisp today as it was fifty years ago. His ability to reveal without stating is marvelous. He is pre-Pinter Pinter. I cannot think of anyone else writing this well on stage and screen, radio being dead.

But as I laughed my eyes filled with tears. It was not nostalgia. I remembered none of these scripts. It was delight, certainly, at the rightness, the sureness of the performance. But it was more. Then I recognized it.

It was love. That infantile, all encompassing love that as a child I gave to Laurel and Hardy. It was fellow feeling extended until I loved them for being so human, so much like me. I love Vic and Sade as I love the people in Ozu’s Tokyo Story because I understand them. I do not want to leave them, and last night could not close the book. I awoke this morning, book still open, light still on.

4 july 1990. In the late morning I go to the American Embassy for the Fourth of July Reception. Great, joyous crush with, oddly, Chinese food. One woman in a red-white-and-blue straw hat. Otherwise, decent attire.

And there was Edward G. Seidensticker. “First time I am invited in years. Why, why, why?” “I think they wanted to look cultural this year,” I said. “Oh, you are such a cynic,” said Ed. Then, “What I really don’t know is why they invited you. Me, I can understand. I, sir, am a patriot. You are No Such Thing.”

Then I circulated through that great cool house, and outside in the garden saxophones were straining and people came up and said, “I bet you don’t remember me,” and they were absolutely right. Lots of military. So many chest decorations one could not tell the American officers from the Soviet.

Hours later, about eleven that night, I was walking home around Shinobazu Pond and there I beheld a familiar figure shuffling toward me. Yes, Edward G. Seidensticker. “All is well with the world,” I said. “We meet on familiar ground.” He stood, swaying, before me. “Dr. Livingston, I presume.” I told him I knew where he had been—to Asakusa. “Right again, sir.” And drinking. “A man may drink,” he said in the flat tones of Dr. Johnson.

Then, “Why do you suppose I was invited? I cannot imagine it. Oh, I was once on the list. Then I was removed. And now, lo, I am back on it again. Who does these things? Who makes up his mind about my destiny in this fashion?” “God?” I suggested. “Less levity,” he said severely, then, “Yours is even more of a mystery. Why would they invite you? Me, yes, for I must admit that I find the Fourth still Glorious. Yes, you may smile in that superior fashion of yours. But I am not ashamed. Glorious!” And tears actually appeared in his eyes. Then, “But you wouldn’t know about this, you old cynic, you. Well, off to home, which is probably not where you are going. I am. To write up my diary, sir.”

5 july 1990. Though America yammers and Japan stealthily buys up the world, there is very little visible of this new war. Perhaps because war is made by governments and not by people. Very visible it is in Washington—I read Ian [Buruma] on this. Another new book names names: the Japan lobbyists—visible even in Tokyo as Japan tries to slam shut the door to protect itself while at the same time menacing everyone else. Oddly no one has said the obvious. America does not have to buy Japanese. No one is forcing it to.

7 july 1990. Eric, required to listen to yet one more of my tales of conquest, said, “But you seem to have deserted Japan in favor of the Third World.” I thought about that and have now decided that it was not that I deserted Japan, but that Japan deserted the Third World.

Me, I have been faithful to that locality. It was the Third World in Japan that so appealed to lubricious me, and now that Japan is more First World than even the U.S.A., the appeal is no longer there. That makes me that figure of fun, the garden-variety colonial imperialistic predator.

8 july 1990. There are no articles in the Japanese language, and the lack of a definite article truly circumscribes. One cannot say “the dog,” one must say “this dog” or “that dog” or “that dog over there.” But the genus dog, that which makes something of a symbol of itself (“the dog is the most widespread of canines”) is not possible. Symbolic thought (man’s triumph it is said) is not triumphant in Japan. I cannot imagine Plato thriving here, with all his absolutes (“Truth,” “Beauty”), but Aristotle thrives because he describes. Maybe this is why Japan is so backward (by comparison) in some areas: philosophy, and diagnosis. And perhaps why it is so forward in others. After all, symbolic thought, logical progression, abstract ideas—these are not all of life, either.

9 july 1990. A cultural collision—Japan versus U.S.—escalates. And yet the antagonists so resemble each other. Japan is an unguided missile. No one is in the control room. When you get the people all pointed in the same direction there is no stopping them. Where is the brake? It is not included in this model. And the U.S.—it cannot even get everyone going in the same direction. People in the control booth, but no one minding the store. Minding the till, however. Both problems are colossal. The U.S., ailing, unable to stop its violent and criminal twitching, unable to care for itself, drooling and weeping. And Japan, locked inside of itself, nose at the windows, gasping for breath, unable to stop its violent impetus, and unable to get out.

Today a taxi driver turned around and said, “Well, I hope you people keep bashing us. That is the only way we are ever going to get any reform in this country.”

A pronounced lack of fellow feeling (except for this sole taxi driver)—that is the harshest and truest thing one can say about the Japanese. In the West too a great lack of that quality, but it nevertheless exists. Here, all too often, the different is seen as inhuman. And even if some feel otherwise they are too cowardly to show it. But how the Americans respond to a show of fellow feeling. They open like flowers turning toward the sun, warming their cold and brittle petals.

25 july 1990. Continuing hot weather. And since no rainy season has occurred, continued fears of water shortage. Tokyo not at its best in such emergencies. Discomfort turns people in upon themselves. They close all the doors and windows, as it were. A train or subway car is filled with complete blanks. This fragile city breaks down upon any provocation. A light snowfall and traffic snarls; a small earthquake and all the trains halt; a typhoon warning and the buses stop running. This is a city designed to work only under optimum conditions, just like the country, and, in a way, just like the people.

In the evening I stroll around Shinobazu. The summer festival is going on. Stalls with plants, and stones, and whole trees. Lots of water. Caged insects, pottery you can paint and bake. This is usually when the city turns “Japanese” again—fans and yukata and geta, and an amount of flesh. Not this year. Just a few young girls, self-conscious (and uncomfortable) in summer kimono. There is less and less of this kind of tradition every year.

With Jim Jarmusch, 1990. unifrance film

17 august 1990. In any event, all other concerns eclipsed in the press by Iraq. What timing. Just when the U.S.A. had lost its evil empire, the USSR, and badly needed a new one. Had tried Japan on for size but something was lacking. This one has everything: military threat, innocent hostages, rape of stewardesses, looting, a lone ten-year-old-girl at peril, and behind it all greed, greed, greed. And, of course, the Threat is Real.

Of a consequence Japan is backed off the front page; carping is forgotten. As another consequence President Bush is off the domestic hook and balancing on the foreign one. The biggest relief for him must be the new and “vital” role for the military establishment, which must have thought it was going to lose a lot of money due to the collapse of the USSR. Now they will get more money than ever and Bully Boy can meet Bully Boy. Just like in a real war.

26 august 1990. To Kawakita Kazuko’s, a party for Jim Jarmusch. Takemitsu Toru there as well. I ask him for a school to which to give the Donald Richie Commemorative Collection of Stringed Chamber Music. He shakes his head. Tells me that he had wanted to give his score collection to the Toho Music School. And they refused. “Just no more space in Japan,” says Toru.

2 september 1990. Learned a very interesting idiomatic difference. It came about this way: I was getting a cold drink at the machine, and a young tobishoku in tabi and cummerbund flashed a broad, white smile and said, in Japanese, “I’m not Japanese, either.” Well, the big, dazzling smile directed at a complete unknown had already indicated that.

He was Korean, from Pusan, and was working high on one of the scaffoldings of the buildings going up around here. Now he was off for the day and thought he would go sit in the park, enjoying what cool the twilight would offer. While this was not issued as an invitation, I took it as such and joined him.

Strong, young (twenty-five, he told me), and with that courtly politeness of the Koreans among strangers. Handsome, blunt, very Korean features; big, hard Korean body, sitting there in the dusk with his legs open. Much taken, I held up my end of the conversation until it was practically perpendicular. But this was also necessary, because his Japanese was not all that good. Mine is much better, and so I kept trying different words until I hit upon one he knew.

He was, I learned, bumming around Asia. He would go to a country broke, work, get some money, and go on. He did not know where he would go next or for how long he would be in Japan. Had been in Indonesia, Taiwan, Thailand, and the Philippines. Always somehow made out. Smiled at this. Big, wide, smile. I could see why he always made out.

Then, seeing my interest in him, he interpreted it in the simplest possible way and decided I wanted to hear about the girls in all these foreign places. He certainly knew a lot about them, including the two, yes, two, whom he had simultaneously enjoyed (friends of friends, no, no money, never), or the one who had enjoyed him just the evening before. Oh, just to think of them made his chinchin okoru.

Here came the interesting idiomatic difference: When we have erections, we sometimes say we “are ready.” The Japanese usually say they “are hard.” But the Koreans say something different. Dae-Yung speaks of his chinchin standing up by saying in English, “It is angry, very angry.” And here was the Korean tobi saying the same thing in Japanese, since okoru means to become angry. How interesting. I wonder if this linguistic fact has ever before been noted by scholars. I tried to tell the tobi about this, but he could not understand. The spoken language not sufficing, I resorted to Braille.

Open, free, in that Korean way, he did not know if the chinchin could okoru at such short notice, but sure, why not, and besides he was tired after work, would like to rest a little. Well, to make a long story short (another idiom) chinchin okoru-ed, and then we went and had a big Korean meal with lots of kimchee.

Name was Lim Chun Sung and he was to leave the next day for Nagoya to work, but would be back on Thursday. We made a tentative date in the middle of the month, the 15th, but he didn’t know where he would be here. At parting, with a big smile, as though it were a joke-gift, he taught me the Korean for chinchin—it is chote.

A most interesting linguistic finding. I had thought that Dae-Yung had made up the angry prick as a part of the pidgin through which we are sometimes forced to communicate. Not at all. It is a part of the Korean language itself. And how interesting that the Koreans have to get angry to make love.

15 september 1990. Surprisingly (since I had not really expected it), Lim Chun Sung kept his promise and appeared, now in a summer sweater with the New York skyline on it, but the same tobi pants.

Over lunch (mainly beer), he told me something more about himself. He is a nomad all right, but this was because he had some trouble in Korea. Just what this consisted of I do not know—his Japanese is really bad. But, it had to do with clutching and slapping and shooting and stabbing and hanging, I guess. I guess, because these are the motions he went through, smiling that big, white, wide accepting Korean smile the while. Also, he was more curious about me. Where did I live, did I live alone, had I any friends? I wish it were possible to trust people, to take them home, to share things, but it is not. At least not people from the park in Ueno.

Later, coming home alone, I cut through the park and saw the young man I often see: crew cut, mid-twenties, nice looking, and somehow sad, also watchful as though waiting for something good to happen in his life. And over the months, I have talked with him. It was not girls he was waiting for, but it did not seem to be boys, either. And though he had some interest in talking about the hentai fufu, it was not voyeurism (which is all they offer), and the resident whore, even, did not know what he wanted though she had her own opinion: “Homo da wa.” So this evening I stopped to talk. Said his stomach was bothering him, gave a quick, apologetic smile, and looked vaguely about him. Just then a large man in a loose coat passed, and his eyes focused and he gave a short salute. And instantly the scales fell from my own eyes.

Of course. Why hadn’t I thought of it myself? “You’re fuzz!” (Deka da!) I spontaneously cried. He instantly assumed that held-in poker face, which means that I am right, and made no attempt to deny anything. “That explains it all,” I said. And so it does. He has no interest in these things other people in the park do, and the only thing he is waiting for is this criminal to walk into his life and get nabbed. “Awful for you,” I said, “to have to perch here every night amid all the perverts and wait and spy and watch.” But he said, smiling as though in apology, “It’s not too bad.”

What kind of criminal is he after? I wanted to know. Obviously no small fry. He is surrounded by these. Is it the Most Wanted Man or something like that? But, he merely showed his polite, closed face and did not answer. “But, I won’t tell anyone,” I said. “No you won’t,” he said, smiling. And I had gotten to know him so well, I’d thought, in the past months. You never know, do you? Things just never what they seem. Wow, isn’t life surprising? etc. So I went my way and left him there, lonely looking, a cop on duty, all night long. Officer of the law, protector of the peace, no matter what the respectable prostitutes and pimps and perverts think.

1 october 1990. In the evening to the opening concert of the week-long series commemorating Takemitsu’s sixtieth birthday. He is in the lobby wearing black, but Issey Miyake black, with a little white (Hanae Mori?) butterfly. Smiling modestly, he always treats these great events of which he is the center as though he is just another guest.

Great event—the Emperor and Empress come. Due to some misunderstanding it was thought that I was diplomatic and so I am given a red ribbon and sit in the first row of the balcony, quite near the royals, separated only by a secret serviceman or two. Hence I can observe them.

They are gracious, as royalty is supposed to be. Certainly there is something Windsor in their waves but perhaps this is because there is only one way to wave. They are attentive during the music and appreciative after it. I wonder what they make of it—one hour and a half of Takemitsu’s beautifully crafted, small sounds. As I listen I remember his once telling me, “Oh, I would give anything to be able to write a good 2/4 allegro.” By the end of the concert I am feeling much the same.

5 october 1990. After some months, ran into Hideki [last name unknown]—a cook who runs his own place in the suburbs, late twenties. Brought him home. He got into all this ten years or so ago. Has no particular feeling for it but it is now all he knows. Has a bad opinion of himself and is consequently hopeless with women, at any rate never met the several with whom this low opinion would have assured affection. Has over the years stopped looking. Men are at least there.

Does everything but only, I feel, because he does not know what else to do. It apparently means little. Small excitement. He stands off and watches himself. Has casual if intimate affairs like with me, but his real friends would be as much strangers to all this as he originally was. He is like a soldier who has somehow strayed into the other camp and stayed because he does not know where else to go. Is pleased to come, is pleased to stay, is pleased to go—is not really pleased at all. But it represents, I guess, something better than nothing.

6 october 1990. Haydn quartets—the delicious Opus 50. They are made up only of themselves. Like something perfectly tailored, not an inch left over, everything accounted for. And at the same time, a world of variety. I like art like that. That is why I like Jane Austen, why I like Henry Green, why I like Ozu, Bresson, and Tarkovsky. And why I do not like the big, inchoate people: Dickens, Liszt, and almost any other film directors one could name. Jonathan [Rauch] said, “You like Mendelssohn better than Beethoven.” Right.

10 october 1990. How Japan is changing. Now the rice market, the sacred rice market, is being opened. This commodity, which now costs seven times what it does elsewhere, will soon be as cheap (well, almost as cheap) as everywhere else. Not yet to be relinquished are all of those middle men who each take a bit off and thus drives up the price, all those distributors. But just as the small store is being eaten by the supermarket, shortly a successful single distributor will gobble up everyone in between. What will be slower to change is the reliance of the large concern on smaller subcontractors. It is these latter who have to work at a low price, with low paid labor. But so uneconomical is this (except for the large concern) that it cannot be expected to last.

16 october 1990. With Frank [Korn] to the Mukai Gallery, where a small ceremony was to be held in honor of his giving a complete set of Marian’s prints to the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts. It was not a solemn occasion, what with the prints being counted, and the curators standing about and Frank pacing and me drinking tea. Still, I wished that Marian could have been there.

She was so ambitious for her art. And now a graphics museum requesting an edition of her work—how happy and proud she would have been. She often had shows at this gallery. I looked around, as I had so often at these various vernissages, but there was no Marian standing there, pleased, and smiling.

Frank took me to lunch and we talked about women. He maintained that he did not care what his women did so long as he did not know. As I well knew, remembering my strange and carnal affair with Marian, which lasted for years but occurred only a few times. I had felt worse and worse about Frank. I liked him better than I did Marian, but how do you let the cuckolded husband know this? We got drunk together once, in the wilds of Otsuka, and I remember almost pleading to let me tell him. Tears in my eyes, I wanted him to listen to my confession, all about his wife. And drunk as he was, with what skill he looped my confessions over my arm, turned me around, and sent me home. I never did get to apologize.

To change the subject I now asked him when his first time was. “Fourteen.” In Vienna. “A business person?” “Ach, no. Wealthy housewife. She used to have her chauffeur wait in front of the school.” “Did you do it in the Dusenberg?” “No, she would take me home. Have tea first. Maids in aprons, footmen.” “Where was her husband?” “At work probably.” Did this occur often? “Every day.” “What a strong schoolboy.” “Oh, no, each day a different school boy. I only got into the limousine once a week or so.” What prewar Vienna must have been. . . .

17 october 1990. I introduce a program of the films of Terayama Shuji at International House. When you look at these short pictures, you look into his mind. His mythology is there—beautiful, distant, wrong end of telescope, the past animated. And I remember him with his odd searching gaze, his rueful little boy smile, his sickly complexion—for the kidneys that killed him had gone bad in childhood. In the first film, the naval officer father takes off his pants, then his fundoshi, and staggers drunk and naked about the old farmhouse; and in the last, Terayama sits in his director’s chair, back to camera, as the play of shadows is dismantled, and then gets up without a backward glance and leaves. And in an hour and a half I have encompassed a life.

19 october 1990. John Haylock takes us out—Eric, Paul McCarthy, and me. We do not talk about sex but rather about religion and eventually about the saints. Paul tells of St. Agatha, depicted as having had her breasts sliced off and put before her on a plate. “Not a proper thing to discuss at table,” said John peering down at his sautéed slices of eggplant.

I gave him Frances Partridge’s new volume of diaries because some friends of his are in it. Duncan Grant, for example. This reminds John of the portrait that Grant did of him, left behind when the Turks invaded Cyprus. When he returned he found the flat a shambles, and there by the fireplace, crumpled, was the portrait. He unfolded it and found that some Turkish soldier had used it to wipe himself. Not, perhaps, a proper thing to discuss at table.

20 october 1990. That sense of “them” and “us.” The polarization; the breaking apart. It is stronger than ever. Visible everyplace. Though I can feel its attraction, I am one of the few, I think, who is aware—or at least aware and disapproving. I do not trust myself. I find myself thinking: them, them, them. How much is real; how much is “me”; how much is “them.”

If it is true that “they” oscillate between open and closed, then they are going into a closed phase. The faces are closed; the minds are closed. At least the occasional opposite is no longer common: the open face, the open question, and the open smile.

Very well, the new bourgeoisie: timid, craven, yuppie. But how much now, I wonder, is it “us” as well—we spurned white lovers. Was it ever any different? Did I not experience the exceptions? And have not affluence and time made these exceptions fewer?

I do not know. But at least I question myself. This is not done by many foreigners here. They hate. It is there, on their faces, and in their books.

21 october 1990. To see Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. How luxurious to sit in a movie and from the first shot know that everything is going to be all right, that an intelligence is guiding, someone whose artistry, technique and morals you can trust.

And what a packed film it is. From the first, information is pouring in from different circuits. There are the visuals, smooth but fast, then there is the dialogue, which is broken, fragmentary, then the voice-over which is echoed by dialogue, and at the same time is not talking about the visuals, and then there is the constant music, hits of the day. And just as Robert de Niro ages and puts on his bi-focals, so the music changes from big band smooth to hard rock hard.

Wonderful shot: out of the taxi, into the back door of the Copacabana, down the stairs, through the kitchen, out onto the floor, the headwaiter, the table carried and laid, the floor show, our people watching, champagne poured. All in one fluid shot, and everything choreographed along the way.

It is intelligent and frantic, just like the director. I remember him here, all eyebrows and tics and malaise. And Isabel Rossellini (they were just married) trying to soothe him (it was in their fake Louis XV suite at the Tokyo Prince) and he was smiling and frowning at the same time. The film is just like him. Style is the man.

23 october 1990. Big party hosted by Oshima Nagisa to celebrate thirty years of marriage. Also perhaps to raise money for the new film. [Tomiyama] Katsue and [Kawakita] Kazuko figured out that a free party always manages (like politicians’ parties) to raise money. Usually nowadays when a person gives a party you are told how much it will cost you to go—equivalent of $100, $200. And so for a “free” celebratory party like this people usually get envelopes ready with $300 or $400 in them. Let me see, if there are 1,000 guests and each gives $300. . . .

At the event, the hall is so big and expensive (The Tokyo Prince Hotel), and the food so lavish (fresh lobster, boeuf Wellington, trout, mango, papaya) that it may have cost him that much. I bring a painting (one of my own) for them. Kazuko says, implying that I am getting off cheap, “Ah, you artists . . .” I ask what she brought. Flowers. “Ah, you florists . . .” I say.

Just everyone there. Everyone a generation later. I see lots of actors I have not seen since the days of Ozu—Tanaka Haruo, for example, now barely visible behind his age. Apparently I am also near unrecognizable. Approached by director Wakamatsu Koji, not seen for a time, with, “Wow, you got real old” (Waa, sugoku toshi natchatta ne . . .)—this from a fiftyish, wrinkled, salt-and-pepper oldster. I playfully pull one of his graying locks, but do not believe for a minute that his observation is without malice. I am, after all, the only one who has refused to take his cinematic effusions seriously.

He makes embarrassing soft-core psychodrama (or used to), and Noël Burch led the French into seeing great cinematic depths in Violated Angels. It occurs to no one that the reason for making it (nurses skinned alive) was non-cinematic. So, Koji was treated as though his junk meant something. And here he is a grand old man. If you last long enough just everyone becomes a grand old man. I am turning into one myself.

Then, a plump but well-preserved Yamamoto Fujiko gives a funny little speech—this long-stemmed Japanese beauty whom I will always remember in her single Ozu film, Higanbana. Shinoda Masahiro, all gray now but still very much the Boy Scout, asking just how I liked his Days of Youth, which I had not at all but can tell him I had recommended it to the Palm Springs Festival. Old Oba Hideo, he must be ninety now, gives the doddering toast, and the president of Toei the main speech. Not Shochiku? No. Shochiku, the company who first sponsored Oshima and then fired him, is not even represented. A scandal, but an expected one.

I leave early and hence miss the unexpected scandal. Oshima had asked novelist Nozaka Yoshiyuki to say a few words, then forgot that he had. Nozaka waited around, drinking the while, and by the time that Oshima remembered, was so smashed that he went to the podium, picked up the hand mike, and hit his host over the head with it. The irate and no more sober Oshima responded by brandishing the mike stand, and finally famous author and noted director had to be parted by force.

25 november 1990. Interviewed for a provincial paper. During it I mention that the Tokugawa period is not over, that self-imposed self-restraint, the acceptance of official guidance, the inability to stand out or stand up, and the fearful cowardice the government fosters—all this is Tokugawa. Wide eyes greet this. My interviewer has never once heard this opinion. Much intrigued. Wonder what it will look like in the paper. Japan-bashing? Probably.

27 november 1990. To my old friend Marcel Grilli’s wake. Since he was a Catholic it is a long, tiresome, self-serving affair with the priest giving his hype, saying such things as, “he experiences the greatest happiness who gives himself unconditionally, entirely, to God.” Service saved and made moving by a talk from Peter Grilli, who remembered his parent with temperance and consideration, and brought to the service the humanity it ought have had from the beginning.

After all this Thanatos, a touch of Eros—I am taken by Eric to the most expensive of the urisen bars. It used to be called The Herakles; now—times being what they are—it is The Fitness Boy. Due to the rain and the fact that it was Wednesday we had the place to ourselves, a number of bulging fitness boys lounging about. When we arrived they took off their T-shirts. In other professions you put on a shirt when customers come.

They sat around in their muscles, gratefully accepted drinks and smiled, and horsed about with each other in boyish fashion. With a bit of encouragement they would have horsed about with us as well. I inquire as to the financial arrangements. Expensive—about five thousand or so for drinks, then five thousand or so to take your choice off the premises, and then fifteen thousand or so for the boy himself, who always expects about five thousand for tip. It all comes up to three hundred dollars or so. “But,” says my host judiciously, “you must realize that girls nowadays cost twice this much.”

A large projected TV image (takes up one whole wall) of young Japanese doing unspeakable things to each other. At the corner, a smaller TV set showing something different—Roger Moore in fact. I ask why. Well, the big one is for the guests, and the small one (James Bond at present) is to give the boys something to look at. The boys, well trained, drain their glasses. Time for another round. The cute one, nude to the waist, stands up humbly and thankfully to clink glasses with us. Humble muscles—the way to the homo heart.

2 january 1991. Last night a New Year’s dream. Very vivid, beautiful, sad, mysterious. I am with Marguerite Yourcenar who is packing, getting ready to go. The train is waiting just beside the davenport, its smoke caught in the drapes. I am admiring her garden at the other end of the room. It is small, but climbs up the wall and is alive with lizards and salamanders, and water runs slowly down from the ceiling, and big snails fall heavily onto the moss beneath. I tell her she will hate to leave it. She says that she does not like leaving, but that it is necessary.

Then she gives me a large block of smoked glass. Holding it up I see, brown, dim, three men, as in a daguerreotype, one of whom is naked and shows a large, soft penis. They all shift back into the shadows, then out again. I understand that in their limited way they are alive. The entire effect is very beautiful, and I reluctantly hand it back to her. “Oh, no,” says Madame, “it is for you. You may keep it.” At once I am intensely, absurdly grateful. I cry, my voice breaks, and I make a small speech. I remember it still: “Oh, Madame,” cry I, “you have given me everything. And now you have given me my death.”

This was said with an insane sincerity, and such a gush of feeling that I woke up, the mysterious inhabited box in my hands as the dream began to fade. I know what it probably means but that is not important. Female approval of my looking at waving cocks may be what prompts that infant outburst, but what moves me is the beauty of it—the brownness of the miniature men, the broad whiteness of beautiful Madame, and my own emotion, surging, like a cut jugular, threatening to suffocate me with feeling.

3 january 1991. The annual party of Kawakita Kazuko and Shibata Hayato at their house—critic Kawarabata Nei, people from the Film Center and the Film Library Council, director Yanagimachi Mitsuo, and the dean of the TV film folk, old (eighty-two) Yodogawa Nagaharu.

And Osugi. He is half of an outrageous pair of twins. Pico is the other, but he has just lost an eye to cancer and is now more quiet. Osugi is not quiet. His screech cuts through any conversation, no matter how distant. And he is continually holding up his hands (a ring on each and every finger) for silence. However, he knows what he is doing.

He is a faggot giving an imitation of a faggot and being very good at it. And since he is a Japanese faggot, the bitchiness is soon seen as a pose and the malice as made up. He has become society’s idea of a homosexual, and by being so has defanged the opposition.

Also, he has another and more traditional role. He is the taikomochi, the male geisha, a traditional figure, very necessary to the better parties. Being men, they can be much more outrageous than women are allowed to be. Camping it up is an ancient tradition in Japanese society.

Also, like the fool at the royal court, the taikomochi is allowed to tell the truth. This is what Osugi does. He is the only critic on TV who is outspoken. Everyone else is conciliatory, bowing to power. Not him. He openly called the new Kadokawa film a stupid little boy’s epic, an infantile executive playing at toy soldiers. Many people listen, not to be amused by camp, but for information. He gets away with it because the accepted opinion is that no one would pay much attention to the opinions of a notorious fag. But everyone does.

I see that he and the venerable Yodogawa are now quite close. He calls the elder critic “father,” and Yodogawa turns to me with a small smile and says, “Of course, I am really his mother.” When they leave (hired car, ten-thirty sharp) people stand up, applaud, as at the end of a performance—which it was.

9 february 1991. With Peter Greenaway—interviewing him. I see it as a meeting, he, initially, as a duel. “. . . and I find the tube more noisy and bigger than . . . well, than, you,” he says before we even begin. I recognize the ploy, having met many British. After charm is on the troubled greensward poured, he loses his suspicions, whatever they were, and becomes interested in himself. Literate, amusing, charming, and pensive, but always testing the way, every step. Maybe he has had bad interviews in the past. Or been interviewed mainly by the English. At first the information is heavy with quotations, Truffaut, Renoir, etc., as though to mine the field. Later it becomes more personal—he is seen playing tennis in the final shot of Blowup. Says that The Draughtsman’s Contract ushered in the Thatcher era and that The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover ushered it out. Laughs. Is intensely concerned over impression made—he and his films alike.

With Sofia Coppola.

With Carmen Coppola, Takemitsu Toru.

11 february 1991. In the paper this morning that Inoue Yasushi died, in his eighties, pneumonia. Not unexpected, but sad. Sad because he was a writer who could imagine. He imagined the wastes of Dunhuang, the ruined Loulan, the various lives of the Emperor Goshirakawa, and the death of Confucius. These he reconstructed with the most scrupulous care, a base for his splendid conjurings. I have never found an arbitrary passage in his works, nor one that was not scrupulous in exposing his sources. It is rare to read a writer who retains the wonder of the past, who shows us the links between then and now, who treats the dead with respect. And now he is dead himself.

I remember him two years ago: I had arranged a showing of a film based on one of his works—Dunhuang. Though the film was a travesty of what he had written, he nonetheless courteously came and was introduced before the screening. He even stayed afterward to answer questions.

A tall old man, kindly and meticulous, a slow and smiling concern for just the right word, and—I thought—a sad gaze as he looked at the insensitive and corrupt version of his work. Or, maybe not. Maybe he knew that commercial cinema has its limitations, and no more resented this than he would have a child’s version of one of his stories.

Perhaps his wisdom was deeper than his taste, deeper even than his ethics. Maybe he simply sat and understood. And I remember his style: plain, particular, always in work clothes, and containing a great strength. He made no appeal, but after you read him you understood and you remembered.

16 february 1991. Party with Francis Coppola and family—wife, daughter, and father. Francis much less up, much more on an even keel. Have never seen him with his father before. “Don’t do that, Francis.” “Oh, you always say that,” says Francis. “Because you always do it,” says father. Then, to no one, “Know how I named him? Looked out of the window and there was this Ford going by.”

Daughter, only nineteen, is a forced bloom. I wonder if she was allowed any childhood. And now pushed into a movie role. Sweet. Unsure. Latches onto me in a nice kind of way. For protection. Looked around and decided I was the least threat. Also, I knew her before. Last time was when she was six. She does not remember but is told I am an Old Friend.

Later, the elder Coppola, Takemitsu, and I have long talk about music. Father talks. We listen. Tells about his lessons with Edgar Varese. “So poor he was. Used to meet him bringing back the garbage pail. Had to dump it himself.” Also, “He had no system of teaching. None.”

More stories, these about playing first flute under Toscanini. The Italian conductor shared the orchestra with Stokowski one season, and when it was Toscanini’s turn he would raise his baton, listen, then start screaming. “Bruta, bruta, that white hair freak he ruin my orchestra!” Coppola also indicates the difference between the two conductors. The Italian knew precisely what he wanted to do when he stepped on the podium. It was all worked out. The fake Russian, real Brit, knew nothing, waited for the orchestra to teach him—emoted, got inspired, etc.

And what is the most difficult flute passage in the orchestral repertoire? Is it the long exposed part in Daphnis? No, not at all, it is the last half of the scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when Mendelssohn makes the flute “hop, skip, jump and skitter right up to the top.”

Takemitsu agreed, again, kind of, to do the score for the film they are making of my Inland Sea. We try to remember how long ago it was when we first met. Thirty years, thirty-five? He pats my cheek, “But you haven’t changed at all.”

No—he is the one who has not changed. Only grown. I heard the viola concerto on the radio the other day. That little boy could create such big, strange, wonderful sounds.

17 february 1991. Fumio in hospital, undiagnosed, danger of peritonitis. I find the hospital, go see him. He is lying curled up in bed looking much like he did twenty years ago when I would come back from work and wake him up. He is asleep and I look at him, needles in his arm, tubes everywhere, eyes closed, breathing deeply.

I weep, suddenly, unexpectedly. It is the sight of time recaptured, to be sure, but, more, it is worry and fear and the sudden possibility of his dying. All of the physical affection I once felt returned, and I put my hand on his arm. Unlike twenty years ago, when he was still young, he now woke at once, his eyes opening, staring at me, knowing neither himself, nor me, then slowly intelligence returns. “Oh, Mr. Richie,” he said, which is what he has always called me for two decades. We talk of the illness, what the doctor has said, how happy he is he changed hospitals, the good care they are taking of him. And we gradually return to being two adults.

There were no more journals for the spring and summer of 1991. The time was spent traveling, writing the Japan Times weekly literary column, all of the occasional pieces requested, and gathering material on early foreigners in Japan for what was to become The Honorable Visitors. His oldest foreign friend in Japan, Eric Klestadt, suffered a stroke.

21 september 1991. Rain, a different kind of coolness, and something determined—autumn. Even a few days ago summer cicadas called—but in vain. Now they are silent—the only sound is the rain falling steadily, purposefully.

Fittingly elegiac sound for the continuation of this journal, sporadic as it is. But I want to continue it for a while because I do not want to see life going by unrecorded, no notice taken other than the living of it.

The early fall of 1991—the Soviets lie in ruins, Yugoslavia ruptures, China simmers, America whines, and selfish, natural, pragmatic Japan, uninhibited by any fellow feeling, opens wide its little mouth. Peaceful here, except for those who came seeking it. The Iranians silently starve in the park, the Pakistanis have learned to batten off the others, the Chinese slyly rob each other, and the Japanese, stepping over the bodies, ignore all these frightened barbarians in their midst.

And Eric’s stroke, his lying for six weeks now, unable to read or write, barely to speak, right arm and leg gone, buried alive. He who took such an interest in everything can now take interest in nothing. No books, no TV, no radio, no music. Nothing left.

His nurse tells me that he throws away all of his magazines, unopened and unread. Though I don’t want them, trying to break through his apathy I tell him he should give them to me. He stares at me in that lopsided way that stroke sufferers have. I say, slowly, deliberately, that he is selfish. I say this because I want to reach him, to go beyond those little nods and noises that so insultingly seem to say that everything is all right. He opens his mouth and gets out a sentence: “I am selfish.” He has to be. He is fighting for his sanity, locked up there with only the windows of his eyes to look out of.

I go every day and the nurses are chipper, the doctor is optimistic, and Eric lies there nodding and trying to smile. Trying to agree, no words coming. And I remember how adroit he was with language, and how proud of it, how dapper he was with words.

His mind remains clear. He knows what has happened to him.

27 december 1991. Go with Chizuko to the private showing of Teshigahara’s new film, Basara: The Princess Go. Director there, and star, Miyazawa Rie. Also the big TV star Beat Takeshi [Kitano], and the well-remembered boxer Akai Hidekazu, star of Dotsuitarunen [Knockout].

He has gotten a little beefy, but is still astonishing looking. Impressed, hence—not like me at all—I actually go and introduce myself, tell him about my titles for his film, about my taking it to San Francisco. At once, with an athletic grace, he is up and off the sofa and bowing. Delighted, has heard my name. Big, beefy hand proffered in acknowledgement of my Westerness. And, the most ingratiating smile. It is one I know from the films and the TV, and can identify. Most people in love with themselves have this captivating smile, one that illuminates inwardly and does not warm. One sees it a lot in sportsmen, particularly body builders. You sure see it in the captivating Akai. He in turn introduces the model turned actress.

Actually little Rie-chan and he have more in common than their presence here. They both posed for the same photographer. She, notoriously so. Shinoyama Kishin posed her in Santa Fe with no clothes, and the portfolio Santa Fe, at nearly $40 the copy, has sold, says the papers, five million. She is more famous now than the Prime Minister who shares her family name. But unbeknownst to her and to everyone else is that the famous photographer has also taken a portfolio of equally nude pictures of Akai.

Once this very long movie is over, everyone has to pee, and I find myself at the trough with Beat on one side of me and Akai on the other. Beat does not get a glance but my eyes still ache from trying to look down at Akai without turning my head. Glimpsed the private part. Blunt, heavy, Osaka-type.

Tell Chizuko, who smiles, then tells me of her bathroom adventure: Little Rie-chan was in tears in the lady’s room. Why? I wondered. Doesn’t know. I think it was the strain of seeing herself for the first time in her first major role. Today was her first viewing. She had not known what to expect. Since she is very good, these must have been tears of relief.

28 december 1991. Cold night, chill wind. Came home early. Made own supper. Sausage from Frank, and French toast on which I put the Maine maple syrup, gift of Marguerite Yourcenar, and treasured in the back of the fridge. She sent it before she went to hospital, just after Jerry died. That was long ago. Now what remained was all lumpy from years in the cold. And it had changed. It had made its own mother, as we used to call what formed in vinegar. But it was sweet, like honey made from very old bees. I could spread it on the French toast. Which I did, and ate it. Mother Marguerite.

29 december 1991. Thinking back over New York—Jonathan [Rauch], Chester [Biscardi], Tom [Wolfe], and Susan [Sontag]. They live in an element I do not. Theirs is the current of contemporary thought, and they swim—mostly against it—and grow sleek. I have no intellectual climate at all. I have no one with whom to speak of these concerns, no one to learn from, no one to teach. For fifty years I have lived alone in the library of my skull. Thus, I have learned to live with the immortals. But, I no longer live with people who think as I do. Consequently, I am out of touch with the climate of my times, except for what I can glean by reading the New York Review of Books, the TLS. Susan once asked me how I managed to keep up with things, presuming that I did. And I innocently answered: “Newsweek.”

31 december 1991. Dinner with Fumio. He is forty-two now and fat. But I still see the boy of twenty-two, slim. And his character has never changed. He is still honest, no cant at all. Tonight we remember the times were got drunk together: Tsugaru on New Year’s, Ishigakijima, Amami Oshima, and (worst) Kurashiki, just before he got married. We were feeling awful and drinking made it worse.

Now he is divorced and I no longer feel awful at all, have not for years. He has his friends; I have mine. We are family now. He also has a hangover this evening. Party at his bar last night. Master has to drink or customers won’t. He has to make them drink to make a living. So he has to get drunk. “Threw up three times on the way home, managed to get out of the taxi to do it.” We eat Korean food. He perks up and by the time the kimchee is gone no longer looks bleary-eyed.

Now sixty-eight years old, Richie found ever-increasing interest in his journals. They became a way not only to salvage experience, but also to assess it. As his attitude changed, so did his tone. It became more intimate and more conversational. In addition to thinking of his journals as a work in themselves and not merely a repository for future use, Richie felt he really had someone to talk to—the future readers whom he now acknowledged. The journals began to show a structure of their own. Richie was aware of this and was interested to see it emerging, unwilled as it were, from the chaos of everyday life.

21 january 1992. New Year’s Day. I wander around. Look at the new buildings. The architecture now is the “kindergarten look”—buildings made of blocks, the cute made collossal. Is this, I wonder, the new rococo? Frivolity embodied by materials tortured into miracles of ingenuity.

With Leza Lowitz, 2002.

22 january 1992. I behave in the Japanese manner. I refuse something, have to be urged, I say I am wrong when I am not. This brings smiles and nods. But I am not seen as behaving “like a Japanese.” I am seen as behaving properly.

23 january 1992. A blond workman, long yellow strands straying from under the hard hat. Face that of elderly Japanese. The fashion last year was yellow streaks in the coiffeurs of the young. Now, in the manner of fashions, it has descended the social ladder. The proletariat has taken it up. It is the latest item in workman chic. Pierced ears are next.

26 january 1992. At the porno. Villain foiled in the middle, true love over somewhat later, and still the film has several reels to go. A divertissement-like coda consisting of pure fucking, no plot. Porno is constructed like the nineteenth-century ballet, like Casse-noisette. Story over at the end of the second act, the third is all dancing—Candyland.

28 january 1992. Dinner with Paul McCarthy. He tells me of being in Thailand and meeting an older professor at university there. Talk turned to Japanese literature and then to film, then to me. “Oh, yes,” said the professor. “Donald Richie. Isn’t she Donald Keene’s wife?” Paul, surprised, said, that no, he was not. “But surely Rizzi is a woman’s name, isn’t it, and they have the same family name; I had always thought that they were related.” Paul explained, but the professor was not convinced.

30 january 1992. Out with Leza [Lowitz] who now teaches at Disney. Told me a curious story about Mickey Mouse. Elsewhere he has four fingers. Apparently easier to draw that way. In Japan, however, four fingers is the common pejorative gesture for the burakumin, the proscribed class. Four fingers shown in derision refers to the four legs of a beast. With the Burakumin League now so litigious, they are taking no chances. In Japan the Mickey and Minnie logos are redrawn.

On the way back in the subway, I suddenly realized that being Japanese must be like being a teenager in an unusually repressive high school. Adolescents are always at the mercy of every fad—the sudden difference rendered identical in that everyone must at once evidence it; the single difference at once branding the person as hopelessly different. The truly different here in Japan are subject to all of the petty molestations common to high schools everywhere: banished, punished, and bullied.

Many Japanese are like high school students: unsure of self, settling for the group every time. And knowledge becomes knowing how to order the proper cherry coke at the single drugstore that is in fashion.

31 january 1992. The Donald Richie Commemorative Collection of Stringed Chamber Music continues to grow—now nine shelves of CDs, lots of LPs, and as many scores of the music as I can find. The catalogue is a dozen pages long now. I would never allow myself anything this expensive. Therefore it is going to a worthy cause, Tokushima University. Thus, I can enjoy it and not feel bad. It is really for someone else, all those anonymous, impoverished chamber music lovers I envision. It also means that I have to buy music I don’t like—the Henze Quartets for example—since I have to be complete.

Today, however, I get something I do like: a Schnittke Trio. Got it in a small and specialized shop in Shibuya, where I had gone to practice the piano at the Kawaii showroom for my performance next week, accompanying He Who Gets Slapped. I have decided on a Schnittke-like score, dissident mazurkas interspersed with inane waltzes and galops, and lots of padding when Lon Chaney is working up his grand theory. But like everything else in Tokyo, the enormous Kawaii practice room complex is full. I can hear Für Elise tinkling in canon, and the “Moonlight” peddling away into the distance. Will return later.

1 february 1992. Woke up at six to a strange light. Usually still gray outside. Now it was white, a pure whiteness as though all my windows had shoji paper. I got up and looked out. All white. It had snowed during the night and now Tokyo was covered. I might have known it was snow as I lay in my warm futon and listened to the quiet. Snow blankets all sounds. I could have been in the distant mountains.

2 february 1992. There was a strong earthquake this morning at four. The jolts woke me and I scampered to the door to prop it open, for it is a metal door that would jam, and then would come the fire.

As I opened the door, there was the peaceful starry night scene, all the snow before me and then, another large jolt. As I watched, all the snow fell—off the roofs, off the trees, off the overhead wires—pulled down in a second by the shuddering ground.

It was like the transformation in the danmari in the Kabuki. Only there the dark curtain drops to reveal the light. Here the white dropped to reveal the black. I savored this wonderful spectacle and was glad to have been awakened to see it. Then back to bed, asleep in five minutes, not at all frightened—too entranced by the extraordinary sight.

3 february 1992. Letter from Darrell Davis, who writes that he finds me “. . . decidedly literary . . . drawn to subtlety and completeness of characterization—of people, places, atmosphere—which seems to me a primarily literary pursuit. Is your continuing fascination with things Japanese a function of the incorrigible textuality of Japanese culture?” If so, this would explain, he thinks, “. . . the metaphorical direction your thinking about the culture seems to have taken—closer now to Barthes and to Burch.”

Maybe. “Literature,” I replied, “has been for me the screen through which I view the world. It began very young when I discovered the public library and realized that I could control my world though the word. Reading was one way. Writing was even better. But,” I continued, “in Japan I never learned to read or write. Hence all signifiers and no signified, just like Barthes.” And this means “control without being controlled.”

I still believe this. When you learn kanji you enter into a great mind-set: Things have only one meaning from then on—the assigned one. My spoken Japanese is all right, but since I can’t really read, it is still fluid, has not been defined by reading and writing, so I do not have to believe in it. My control is there, but only in English.

Darrell also says that he cannot imagine my feeling “at home” in Japan because, “. . . it is hard to imagine sustaining the kind of detachment necessary to write, the kind of reflective commentary you do when you’re at home.” Maybe, but then I find anyone who is “at home” in this universe a person seriously deluded. I would hate to be at home. But I do sometimes now think of myself as a bridge. But what kind? Suspension? Single span? Draw? Arch?

4 february 1992. Am snappy with the service. At Wendy’s the waitress is not paying attention to me, stares at the ceiling, looks around, peers into the kitchen. But, I am her customer, he to whom she owes her very job. I am cold as ice when I finally capture her attention. My eyes speak stern volumes. My tone could freeze. She stares. Does not comprehend, but is hurt. I am mollified, having caused deserved pain. But I do not relent. I keep it up until my hamburger is in hand, change grabbed. Only then do I permit myself a moué and turn away.

Turn away to look at myself. Why did I do that? How could I behave that way? And then, there swims before me another pair of eyes, light blue, cold, outraged. My mother! When she is with the help or on the telephone talking to a reluctant tradesperson. My mother, ordering the service about. That was whom I turned into. I bite into my Wendy, pensive. I begin to believe in genes.

The anima. Am I still carrying her around with me? It is undignified for a man going on sixty-eight to still act like the worst in his mother. It is unnatural. Or is it? Maybe everyone does this and either does not notice or is too ashamed to admit it.

6 february 1992. Invective accelerating. The U.S. and Japan cannot say bad enough things about each other. Bad blood in the family of nations. Battling siblings. Easy enough to understand, though nonetheless deplorable. The U.S. slipping, lost its great supporting enemy in the collapse of the U.S.S.R. It needs another one, quick. Japan, slithering out of control, all cool heads hot in this drive to greed, displays an enormous insensitivity to others, and its own real concern for itself. America, angry, finds Japan an ingrate after all we did for it, and Japan, tired of being the idiot younger brother, makes remarks about the American lack of work ethic. All of this is easy to understand. What is not remarked upon is that the bickering is good for the economy of both countries. Just as wartime makes money, so do unfriendly relations. I don’t think anyone really believes in this animosity except the stupid. But there are so many.

12 february 1992. A Ginza gentleman’s club, the last one. It is immaculately prewar. The paneling is light oak and the floor is parquet. The style is late art deco, with Aztec lines and a Grand Rapids finish. The small windows are leaded in the Frank Lloyd Wright manner, lozenges of gray and yellow. I look at walls, and there it is—a reproduction of Maxfield Parrish’s Daybreak, one androgynous ephebe leaning over another, against sun struck mountains out of The Arabian Nights—the same as that which hung over our Ohio piano and over which wandered my infant eyes, wondering at the immensity and beauty of the world.

13 february 1992. The sound of a temple bell. One does not hear the strike. Rather, the sound starts small and then rapidly builds, a soft explosion. The note is like some animal opening its mouth wide, the brazen roar afterward emerging.

14 february 1992. At the game center. Boy and girl playing Cop Killer, shooting electrical impulses at uniformed cartoon figures, who splatter or not. Two controls. He is shooting most of the cops, but she pulls her trigger now and again and remembers to smile when he turns to look at her. I see he has a package of chocolate on his lap. It is St. Valentine’s Day. She has given him the chocolate, as is customary, and he has taken her to the only entertainment he knows anything about—video games. She stifles a yawn when he is not looking. But he rarely looks at her. He is interested in the game. Pow! Wow! Zap!

19 february 1992. Japan-bashing by America has begun to make slight ripples here. I find myself regarded on the train platform or in the subway car. Just regarded, assessed. I try to look European.

As this schism grows I am aware of other cracks. Ones I have myself climbed into. Smoking, for example. Since stopping I have become militant, a born-againer. I cannot “stand” to see people smoking where they “ought not.” And so I march right up and tell them. And what a full, warm feeling I experience when I identify myself as a member of the “right” side. I feel for a moment almost a hate. It is warming, like a flame. This is what bashers must feel all the time—on either side. And they get hooked on their highs. Prejudice is addiction.

24 february 1992. The shinchoge is blooming in the cold. Spiked little blossoms of lavender and mauve, and giving the scent of summer right in the middle of winter. A lush, strong, tropical perfume—fleshy, like gardenia or magnolia—wafting from the small flowers, smelling of hot nights on these cold days.

Not a popular plant in Japan, however. The reason is that it was planted around latrines to temper the stench. The reputation lingers no matter how nice the smell. I had a plant in the house once. My cleaning lady’s eyebrows arched. This was not done.

25 february 1992. Dinner with [Numata] Makiyo. Back here for dessert and coffee, he asked to see the pictures I had taken of him on our various trips—in Europe, in America, and him at university in Hawaii. He is now thirty and had, I thought, done well. He has his own company, has branches abroad, is married, and is taking care of his ailing parents. Success.

Recently, to be sure, with the collapse of Japan’s inflated land prices I thought that as a developer he might be experiencing a slight recession. But I was not prepared for his suddenly telling me, in that earnest and schoolboy fashion of his, about a property in the desert outside Los Angeles that he has bought and is now making payments on.

Finally I understood that, in the oblique manner that has always been his, he was offering it as collateral. Collateral for what, and to whom? Well, to me. He needed a million yen before the end of the week.

This was surprising. I had not known things were so bad for him because he had never told me. I did not want the collateral, I said, but I would transfer the amount to his account tomorrow morning. One millon yen is a lot of money—eight thousand dollars. He promised to pay it all back by the end of June. Then I told him how surprised I was, and gently chided him for not letting me know the true state of his affairs. Gentle though I was, this push was enough.

He suddenly broke into tears—the first in the eight years of our friendship. The strong Makiyo cried like a man, choking back the sobs, face awash. Finally he said, “I wanted so much to succeed.” I knew that was so. For as long as I have known him, it has been winning the marathon, and believing that if you throw yourself into it you will get it, whatever it is. “My Way” is his favorite song. And now, in front of me, the person who knows him best, he must admit failure. I told him what one tells people—the truth: One failure is not for a lifetime; everyone fails at something.

After a time the sobs stopped. He wiped his face and smiled ruefully at himself as though he were his own little brother. I gave him more Kleenex. He understood me, and my reasons. I could no longer continue to embarrass him by witnessing his tears—so in the most open and friendly fashion I told him to get out. Tomorrow I will go to the bank, and at the same time will now see my friend as an allegorical figure. Makiyo—Financially Over-Extended Japan.