During the following year Richie suffered a heart attack, which resulted in his stopping smoking. He also began to receive awards (the first Kawakita Foundation Award was given to him), and he traveled. In 1983 he went on a world tour with Mizushima, who was having second thoughts about his marriage, though he had become a father. Richie’s journals continued to be composed not so much as a daily record of occurrences as a reaction to those things that he wanted to preserve—for example, the meeting with Marguerite Yourcenar below, a longer account than that which he published in The Honorable Visitors.

16 october 1982. Dinner with Marguerite Yourcenar. She is with her companion, Jerry Wilson, sitting there in her coat and scarf in the big, cold downstairs room at the French Embassy Residence. The scarf, of loosely woven wool, is the same color as her intensely blue eyes. It is these extraordinary eyes, which though now hooded with age, give this elderly woman the look of youth. They and the mind behind them, which is, as I discovered, as agile, inquiring, amused as that of an adolescent girl.

We talk of her work, she with complete detachment. “I am translating a play by Jimmy Baldwin. He is a good friend,” she says in her accented English. I mention her earlier translations of Negro spirituals. “Oh, yes, and that is not all. Now I am beginning to translate blues and soul. I am interested in this, and amusing it is to try to translate precisely.” Here she gives her young companion a glance that was both an affirmation and an acknowledgement, and I realize that he is interested in blacks.

She smiles. A strong, round face, wrinkled as a winter apple. A peasant face, Breton, Flemish, like the faces of Brueghel. Nothing of the aristocrat in her appearance. Firm, round body. But the youthfulness of her expression, the adolescent clarity of her eyes, they are from something earlier: an illuminated book of hours, Aucassin and Nicolette.

I ask about work not yet translated, and happen to mention La Nouvelle Eurydice. “Oh, no, not that. What a bad book. You see I had had some success with Alexis, my first book. So I thought that the second should be larger, grander. It was a great mistake. It will not be translated, nor brought back into print.” I ask if there are other of her own works that she thought badly of. “Only one. My little book on Pindar. So bad, so inflated.” What then is her favorite, if she has one. She thinks and then says, “It is difficult, but I do think probably The Abyss.” From then we speak of her biography. “I am supposed to be writing the third and last volume. But here in Japan of course, I am not working at all.” When would it end? “Oh, around 1930 just after I started to write. After the death of my father.”

When she speaks of death I notice now, and later when she speaks of the death of her companion, Grace Frick, that she looks through and past me. Those extraordinary eyes, distant. Later, following what train of thought I do not know, she again speaks of death. “I shall not kill myself. Not like Hadrian. Oh, he did not kill himself, to be sure. But he often thought of it.” Again her eyes sought the distance. Had she too thought of it? This I do not ask.

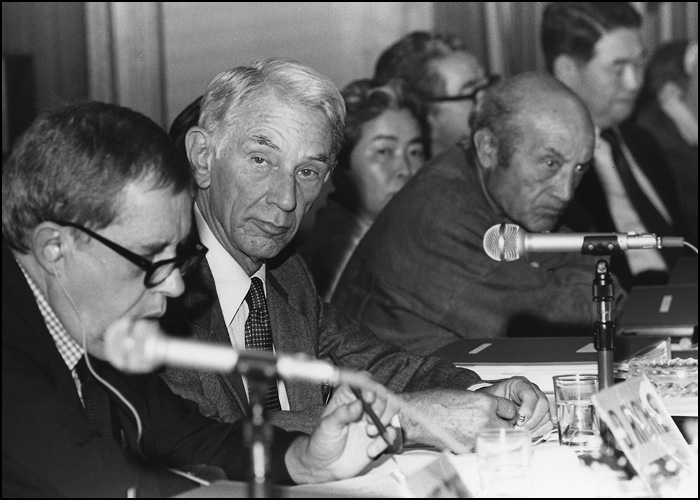

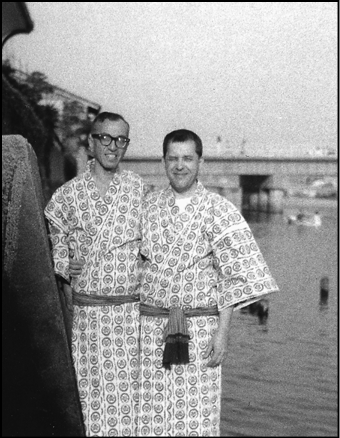

With Edwin Reischauer, Isamu Noguchi. Hakone, 1982.

I take them to dinner at the Chugoku Honten, which can be trusted to feed you well. Since neither she nor her companion eats red meat, we have abalone, sweet and sour fish, Peking style chicken, and green vegetables in cream, ending with fresh litchi and drinking Chinese wine the while.

Jerry Wilson is around thirty. Open, American face with reddish hair cut very short, a small gold ring in one pierced ear. His French is fluent, with a heavy American accent. Where did they meet I ask. “Well, let me see, it was several years ago. He came with a television team that was doing something with me and we discovered that we had much in common.” Period.

He sometimes lives with her and always travels with her. Last year they went to Egypt together and now are on this Asiatic tour. The conversation turns to Mishima, about whom she has written a book, and then to homosexuality.

They had been to the Kabuki and had heard that there was a place where the young onnagata gather to relax. I tell them that there might be such a place, but that it is unvisitable. Instead there are, of course, onnagata-like places where I could take them, places where the young men are more feminine than any female. This, she said, she would like to see, and so in several weeks this is where I shall take them.

Much as I want to know more about Madame Yourcenar’s long interest in homosexuality (“Alexis,” Hadrian, Cavafy, Baldwin, and Mishima), I ask no more. She had been described to me as taking the interest of a “scholarly amateur” in the subject, and so it seems to be. Her interest is detached and exists for itself, offering no further information about herself. It is an interest, I would imagine, rather like Colette’s. And for many of the same reasons.

I ask her if I could ask her a very personal question, and she smiled and said that of course I could. So I ask a question I have long wanted to. What were her influences; who had formed her; what had she read that had made her style? She thinks and then says, “You must understand that when I was young I read everything. I read until there was no more to read. I devoured. And I retained. Therefore the influence upon me, a very strong one, is the influence of everyone. This is not a satisfactory reply I know, but it is the only one I am capable of making. Shakespeare, Pindar, Basho, all the novelists—everyone made me.” Pressed, she said, “Maybe most the Greek poets. Maybe it was them I most loved. That being so, maybe it was they who most formed me.”

We then talk of other things. I ask her if her admission into the Academie Française was time-consuming. Mr. Wilson laughs. “No,” he says, “she never goes.” She turns to me and smiles. “It is, you see, a club for elderly gentlemen and so I felt I ought not attend and they feel, I should think, relieved that I do not.” I ask if they pay her anything. “Not a penny. To be sure, the more assiduous” (she appears to regard the word and smiles, as though it is one new to her), “become caretakers in old houses or curators of collections and thus get an apartment free, but otherwise there are no material rewards.” “Only spiritual ones,” says Wilson and they both smile.

After jasmine tea, we leave. She turns and I help her into her wool coat. From the rear she is a shapeless old peasant woman. She turns and I give her her handbag and she thanks me with a glance from those marvelous eyes. She is now a proud, sure, serene adolescent.

18 october 1982. At the conference Isamu Noguchi, for the first time since I have known him, talked about himself. To be sure, he usually talks about his opinions, beliefs, etc., usually at length. But here he spoke of what it felt like to be him—Japanese ancestry, born an American, back to Japan before the war, back to America, his work, then back to Japan after the war, then back and forth, back and forth. He spoke about what he discovered in Japan and in himself, talked about stone and rock.

Noguchi himself has become rock-like. He is veined and seamed and sits very still. As his outside has grown this patina, so his inside, his opinions, views, have softened, mellowed. It used to be that Noguchi’s ideas were the most adamantine thing about him. Abrasive. You could cut yourself on them. Not now. The rock speaks softly.

Later, the long day over, we have coffee and talk of the Stravinsky/ Balanchine Orpheus, for which he did costumes and sets. He complains that in doing everything over for its revival he had to make everything larger. It was designed for the small City Center and not the large Lincoln Center. “It is really a chamber work. That is how I saw it, too, with my little rocks. Now those little rocks are enormous so that they will be visible in all that space. A great mistake. Scale is one of the most important of all things and we violated our scale. No. I violated it. Balanchine and Stravinsky kept things the same. Mine was the part that had to give. I regret it.”

19 october 1982. Lunch with Edwin Reischauer. He talks about the Great Kanto Earthquake, which he remembers. Wasn’t in Tokyo but in Karuizawa. Nonetheless, the shock was so great that it knocked over chimneys and killed one person there—crushed under a roof.

What he remembers well is the massacre of the Koreans, which began at once, only hours after the earthquake. They, the minority, were being held responsible, not for the earthquake, but for the terror and despair of the Japanese themselves. Ridiculous charges: poisoning wells and the like.

He remembers a child, a girl, deaf, and consequently unable to speak. The crowd confronted her. She could not tell them that she was Japanese. They tore her to pieces. Whether she was Japanese or not is not the point, of course. A child was murdered.

Reischauer simply tells the story. He makes no apology, makes no attempt to account for what happened. Takes for granted that this is what the Japanese do—or did. Does not say so. No moral reflections at all. He knows his people very well. He knows and he accepts. So do I.

25 october 1982. A curious dream. I was at a party at someone’s house. The style was art deco and I knew that it had been made in the 1930s. Also, as I gradually became aware, this was the 1930s. The others were all men and we were sitting around drinking. I was speaking with Ravel. It took me some time to recognize this because he looked nothing like his pictures.

I also realized that I knew what was going to happen and he did not. It became very important to determine precisely in what year all this was occurring so that I would know how much time he had left. But he was charmingly vague. Pleased that I knew so much about his work, that I loved L’Enfant et les Sortilèges (“We must be the only ones, no one else knows of it”). Finally, I learned that it was about 1934 and I realized that the charming man in front of me would be dead in three years.

So I told him about his last composition. He was very interested since he had not yet started to write it. I told him about the film Gaumont was making on Don Quixote and the music they would commission. “For Panzera,” said Ravel. “No, Chaliapin,” said I. “Oh, dear,” said Ravel. “That’s all right,” I said warmly, “You will not win the commission. Ibert will. But your work, called Don Quichotte et Dulcinée , will become much the more famous.” “Well,” said Ravel, “that’s something at any rate.” I did not tell him about the auto accident, the brain damage, the inability to compose, the operation, and the death.

Or perhaps I did. I was feeling the awful pathos of knowing what was going to happen, the inability to stop it, the touching innocence of the victim. Dreams mean something we are told. What does my role as messenger from the future mean? Anything?—Or is the brain at sleep really an idle computer amusing itself by punching at random?

28 october 1982. Dinner with Marguerite Yourcenar and Jerry Wilson, all of us taken out by Eric Klestadt—to eat at the very elegant Kicho, then for coffee at the equally elegant Nishi no Ki.

Madame Yourcenar at one point speaks of herself. Her mother, who died when she was young, was Flemish. Her father, who died in the 1930s, was able to read her first book, Alexis, in manuscript. He was a great reader. Books were all over the house and Madame Yourcenar began reading very early.

“What did your father do?” “Nothing at all. Nothing.” “But how did you live.” “Land, tenant farming.” “Did that devolve down on you?” “On neither myself nor my older half brother. My father lived gloriously. He lived right through it.”

Jerry tells me she is seventy-nine. That, I think, is quite old, but years are apparently light upon her. She speaks of catching cold easily. “Fortunately, I caught my cold in the most beautiful place—Matsushima.” And Jerry says that sometimes she forgets. Which she probably does, but part of the fond way in which he says this has to do with their relationship as much as with her forgetfulness.

She is fortunate she has him. He is devoted. Always ready with the wraps. Helping her, smoothing the way. They have that mutual look that certain married couples have. What is hers is his, his, hers, the look seems to say. They both turn to answer the same question.

During the conversation I learn that she is claustrophobic and once had a bad attack of asthma in the Paris metro. I describe my being caught in the same metro and experiencing the pangs of the same affliction. We smile and nod. Something in common.

She is very interested in Eric and his background: German Jew, fled, came to Japan. She also knows how to be the perfect guest. I admire this. Adaptability. I would imagine that she has a long experience as guest, being gracious with host. I do not know how she would be as hostess. Perhaps not so good. I can imagine her becoming tired of her guests very easily.

But now it is midnight, time to move on to the transvestite bar, which will have to serve as the place where the onnagata meet.

5 december 1982. Invited to dinner by Madame Yourcenar and Jerry, just the three of us, at the Takanawa—sole for her, abalone for him, steak for me.

I watch her and Jerry together. It is like grandmother and grandson. It is also not like that at all. They are as much themselves with each other as though they have been married for years. At the same time, however, he is also there for her convenience. (In the bar for pre-dinner drinks, Madame went ahead. Usually it is he. This time he followed her, large among the little tables, and said, with a smile, “Where she goes, I follow.” Said this with affection and good will.) At other times she is as permissive as a mother. Jerry did not like the Noh and, carried away, he turned it into a little act. He also, without knowing, turned himself into the very image of his Arkansas mother not liking the Noh. He used words (“land’s sake”) appropriate for her. This unconscious imitation apparently pleased Madame. She also offered further reasons for finding the Noh boring. But since she had not actually found it so, this was done with some playfulness, yet with no hidden acknowledgment to me that we were at this point seeing through Jerry. On the contrary, it was like a mother reveling in her child’s foolishness.

Later, talk about Mishima. Madame astonished me with the pronouncement that his wife could not have much loved him, since she survived him. I asked if she were indeed that romantic, that she thought a great love could not survive a death. “Oh, yes,” she said, cheerfully, “I’m just that romantic.”

“But, you,” I said, “survived and lived to write Les Feux.” She looked at me as though trying to guess how much I knew. Since I knew nothing, this did not take long. She said, “Yes, it was a difficult time but it could not compare.” Consequently, I learned nothing about this particular crisis of the soul she had undergone, and of which I had only vaguely heard.

She wondered if Mishima’s wife knew, then said, “Of course she did but she did not want to believe, did not want to know.” Said that sometimes the person himself did not want to know. Mentioned Henry James as an example. I told her I had heard that Leon Edel had kept back letters from James to Hugh Walpole that proved what the biographer did not want to believe. “Yes,” agreed Madame, “because otherwise much of James’s The Pupil, would not be understandable. Madame Mishima, like Edel, was merely trying to hide, not wanting to admit.”

Not wanting to admit was also treated as just as normal, as was the homosexual impulse itself, however. Everything is normal in Madame Yourcenar’s world; hence everything is understandable. It is not that she is Olympian, as has been said, but that she is so absolutely accepting.

She did, however, find Japan the most difficult country she had ever been in. The simplest things defeated them. They went out to buy pencils and returned, defeated, no pencils. I wondered how this could be and then realized that her world is entirely one of language and she has no language for this country. Some kind of converse, this is what she expects, and this is what she misses here. Not that it is not here. It is that it is not open to her. No Japanese language, and the Japanese themselves not often making the intuitive leap one finds admirable in Mediterranean countries. Blank incomprehension or evasion is what she is met with. This intrigues and puzzles. Of a consequence the two of them go mainly to the theater. Jerry simply “adores” the Kabuki and so this is what they have seen. Some forty hours of Kabuki since arrival—both because of interest and because it is, oddly, a place of refuge from Japan itself for them.

Looking at her I was suddenly struck by a resemblance I did not before see in her similarity to Colette. Not that they are both women, not that they are both androgynous, but rather their interest in detail, their fascination in how something is done, their acceptance of the natural world and their celebration of it—a combination of interest and awe. I watched her eating her sole with interest and concern, watched the way she savored a chopstickful, crumbling it with her lips.

What was it in this gesture? Something I have seen in Flemish paintings. Then a phrase, not a particularly good one but a descriptive one occurred: She is a patrician peasant. The lips are those in Brueghel, the eyes are those in the Livre des Heures. Feet squat on the ground she soars to an enormous height, her eyes (those eyes—she shares them with Simone Signoret) looking into the far distance. Is that the reason for her charm?—that she manages to encompass a dichotomy, closes it, and consequently appears so whole.

The evening was over. She picked up the tiny pot of living plumeria I brought her, and held it as though warming it in her rough hands. She was not tired, but she would be. I took my leave. She and Jerry looked after me as I departed, the two of them there, a woman who likes strange and beautiful sons and had none, a young man who likes old and wise mothers and had none.

10 december 1982. I learn today that Herschel [Webb] is dead. And my first thought is that this is impossible because he was so young. But then I remembered that that was thirty-five years ago. Afterward he went to teach at Columbia and became a scholar and a full professor. I was here; he there, and we rarely met. And now he is dead. I had heard that, as I remembered, he retained his taste for martinis but I did not know to what extent until now. The Herschel I remember, though, was not a teacher; he was more like a student, an endlessly inventive one. And as I remembered him today I heard from somewhere the opening bassoon solo from Sacre and Herschel singing along, “Oh, baby, see the moon . . .”

12 december 1982. I go to Kamakura. I sit in the train and look out of the window as Herschel and I had thirty-five years ago when we went down to spend the weekend at Dr. Suzuki’s house. But I will get off at Kita-Kamakura today only to take a taxi to the museum.

Today is the last day of the Italian show and it has three Morandis I want to see again. One is particularly fine, all made of a single color, a reddish gray, against which the objects stand, their own contours often of the same color so that line becomes invisible. A work from 1928 to 1929, done with the paint oily, lots of brush marks, all invisible from three feet back.

Walking down from the Hachiman I notice a small print shop into which I had not gone for years. Go in. A small pile of original prints, all of them overpriced. And then, at the bottom, a beautiful Toyokuni. A tattooed man being ferried across a river on the shoulders of porters. Obviously just the middle section of a triptych, but quite splendid nonetheless. Done mainly in blue and red. Red for the tattoos, blue for the rest, with that Delft-like shading from very light to very dark. I admire, put it regretfully to one side, then notice the price. It is only fifty dollars. Upon asking why I am told that, though a first impression, it has watermarks on one side and, being part of a three-unit panel, is not complete. I do not argue—a Toyokuni this superior belongs in a museum. Nonetheless, it is now here in my house.

Suddenly I remember a dream I had last night. It was a continuation of something that really happened two years ago. What really happened was that Francis Coppola called me up, was in a bar across the street, come on over. There was Toru Takemitsu, a good friend, and Richard Brautigan, whom I had been avoiding. He knew this, had been told, and so now refused to shake hands, glowered, then turned to Coppola, and with that whine of his said, “But, Francis, you know you are making masterpieces, you know that, don’t you, man?” I talked with Francis and Toru and then went home. Wondered after just why I had been called out. Because they were all drunk? Or was Francis staging one of his scenes? Never found out, but that was what happened. Now the event had a continuation in my dream last night. Continuation: I punch Brautigan and lay him out.

13 december 1982. Did not sleep well last night. Do not sleep well unless I am alone or with someone I know well. Did not know well the soundly sleeping Hisashi, having only met him an hour before as he was dozing in a Steve McQueen all-nighter. Sturdy, rural, from Tohoku, twenty, in for a Saturday night in the city, not caring at all what happened to him so long as something did. Now, satisfied with his new experience, he sleeps with the audible sighs of farm youth everywhere.

In the morning he admires my paintings. Talks about their space (kukan), knows what he is talking about. Most Japanese know about art, and all can draw maps and carry tunes—and dance. He shows me some of the steps for the local Tohoku matsuri, thumping big-footed in his underwear. It is as though we have known each other for years—the gift for instant intimacy that the rural young still have. Later, went to have breakfast at the Park where I taught him the intricacies of eggs benedict.

7 january 1983. Sogetsu-ryu ikebana, the Hilton, the Pearl Room—chandeliers made of ropes of pearls—big party, mostly women, most in kimono, much display of good manners, lots of food including seven different kinds of cake, and lots of money spent, but then Sogetsu has it—the most affluent of all the flower-arrangement schools, thousands of pupils all over the world, and leading all the rest when it comes to paying taxes.

Iemoto Teshigahara Hiroshi, now grand in hakama, white-maned and patriarchal, makes the opening speech. And I remember when he was still a schoolboy, wanting to make movies, and getting to—the money coming from old Sofu, his dad, who had founded the lucrative school. Then Sofu died and Hiroshi’s elder sister took over, but then she died and (Japanese arts schools having lineage, just like royalty) the position of iemoto devolved upon Hiroshi. He hated it, knew nothing about flowers, but the pressure of the school was stronger.

That was three years ago. Now he has become what was wanted—the head of the school. He handles himself well, has been a great success. The ladies love him. He speaks in respectful tones of his father while his mother, her hair now a light violet, sits and beams.

He has done a perhaps typical but nonetheless I suppose admirable thing. Since he could not change his circumstances, he changed himself. Knows all about flowers and the other materials (cellophane, plastic, egg-crates) avant-garde Sogetsu makes use of, left off his tweeds and suedes, and is now usually in kimono.

At the same time I wonder just how much this cost the director of Woman in the Dunes. My Western self says that he sold out. But my Eastern self wonders if what he did does not indicate a higher wisdom. We are so prone to think any accommodation a surrender. Hiroshi has chosen continuation. If the cost has been great, he seems—standing there, leonine, grand, a master—already to have discounted it.

7 june 1983. Rereading The Immoralist. First read it nearly forty years ago. Sitting in Hibiya Park, as Michel sat in the park at Biskra. How old was I then—twenty-four? Proper age for reading this book. I am no longer at the proper age but I am curious. This book much influenced me. What is it like now; what am I like now?

How little I remembered of it. Almost nothing. And how I had colored what I had remembered. One’s memory of a book is never accurate. It is a memory of the impression the book made. The impression now is much different. Michel I once found admirable. Now I find him pathological. Not in his immorality, of course. Rather, in his symptoms.

I suppose it is because I recognize them. I am impressed now rather by the truthfulness of Gide’s observations about his travels with his wife, the compensatory neuroticism of the husband. The urge to rush from one place to the other, as though a new goal will be somehow better because it is new. I recognize this, having experienced it twenty years ago with my own new wife.

Do I now experience this because Michel so influenced me forty years ago? I wonder. Probably not. I was attracted to Michel because I was of the temperament to experience what he did. It was thus not Michel’s rebellion that attracted me, but his feeling of guilt. This I seem to have recognized.

It is this that leads one to feel so responsible for another, to use them for this purpose, then to dislike them for it, and then to feel guilty for the dislike. How vulgar—because it has nothing to do with them. It has only to do with self.

And perhaps that is the true immorality of Michel—of all of us. This use of others for one’s own dramatic purposes. As though one would not exist otherwise.

And I sense the chill that comes when one suspects nonexistence—the flight that follows, the rationalizations, and the panic terror. Gide, however, makes very little of this. Did he know what he was describing? Perhaps not. To him, Michel is still a hero.

8 june 1983. Lunch with Richard Brautigan, one that came about in a curious fashion. I had seen him at a Parco opening and went up and asked why he had refused to shake my hand when he was here before. He was confused, remembered, said it was all a misunderstanding, as it indeed must have been; then last week he sent me a letter, very small writing on hotel stationery: “It is always very pleasant to clear up misunderstandings and I admire your courage to come up to me when last we met to talk it over and have it done with.” Then he asked me to have a drink with him, and that turned into lunch.

Denim and corduroy, granny glasses, wispy red hair, uneven red mustache. Bright blue eyes, the moustache concealing an affable mouth. The aging hippy persona is there but is mostly due to the clothes: the studied appearance of the unlearned, does not know foreign languages, careful mispronunciations. Part of it is a pose, I think: the American anti-intellectual, Mark Twain, Innocents Abroad. But not all.

He talks about himself, which is perhaps to be expected, given our manner of meeting. He is not precisely attempting to justify himself, but is giving me a lot of information. Among the things spoken of is how different the public persona, created by “the media,” is from the real self.

Speaks of Norman Mailer, apparently a close friend. Finds him generous, sweet, understanding, warm—all things different indeed from the public persona. From there we speak of ways in which the persona may be used. It is of use in getting people to go to bed with you. In fact, fame-fucking is a known result.

He has had much experience. Further, he prefers his partners young. His persona is very reassuring. He is filled with earth-wisdom and, as one of the original hippies, is by definition kind and understanding, things that female children, males as well, find attractive. He is at present with a young girl, “young enough to be my daughter.”

We drink sangria, growing more mellow with each sip, and eat an excellent Spanish bouillabaisse. We talk about Francis, we mention the very bar where we first met and where the affront occurred. But we do not speak of it, being much too well bred to do so. I find his air of the faux-naïf very refreshing but I still do not know how faux it is. Perhaps it isn’t. What he finds in me I don’t know—we speak little about me.

17 june 1983. Dinner with Paul Schrader, in Tokyo for the Mishima movie that he will direct. Talks about difficulties with Mishima Yoko and her efforts to make her dead husband into something more fitting. We talk about Yukio. “That is undoubtedly him. And that is just what I can’t put into the movie, damn it. Not that we can’t, you know. We have not signed anything away. We want to make our kind of movie, not hers.”

I say that Mishima himself would probably have sided with Paul; that he would not, I think, have approved of the amount of censorship that Yoko is exercising. He was enough of an exhibitionist to want to project a little of the truth at least—to tantalize his audience, if nothing else.

Paul still has his engaging stutter, still has his charm, his bent smile, the sudden crinkling of the eyes. These he somehow kept in Hollywood. Or maybe has them back now that he is here. Talks of how he is going to structure his film: Mishima in real life, then Mishima as a boy, then Mishima as one of the characters in his various novels. These three will have a kind of conversation, and somehow in the interchange he hopes that something like the real author will appear—and that Yoko will not notice.

He is going to have his production man over; it is going to be all studio; it will be completely professional, all designed. I do not say that this is not the proper work for a Bresson scholar. But Paul never became Bresson and I suppose there is no reason why he should have. One need not become what one admires.

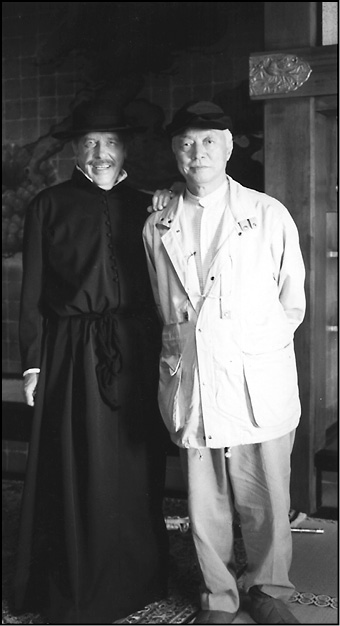

With Mifune Toshiro, 1983. donald richie

I see that Paul bites his nails now. Why do I find this engaging? Sign of weakness? No, a sign of something else, something more human. Paul presents such a reasoned and optimistic self that one welcomes something as human and doubtful as nail biting. Cutting him down to size? No, I don’t think so. Rather, something one recognizes, sees as authentic.

18 june 1983. Lunch with Francis [Coppola]. He is here to convince Mishima Yoko that a film on her late husband is a good idea—that the writer, director, and he himself, all are working for the proper picture. The difference lies in the interpretation. She wants the whitened sepulcher she has been daubing away at these last years. They want a commercial film that tells a bit of the truth. Consequently Francis is properly cynical, or as cynical as he ever gets.

“Is it true,” he wonders aloud, “that a director is only as good as his last few films? Is it really like a ball game? Three strikes and you’re out?” From anyone else, given Francis’ recent experiences, this would certainly sound like irony. But when he asks this, his eyes gentle, his large and infantile mouth questioning, one detects no cynicism. Just the kind of wonder that such a thing might, perhaps, after all, be possible.

Francis is very childlike. Having put on weight again, he is like a fat little boy, and he has all the gentleness and sudden wildness that one associates with youngsters. A bearded baby, he is given to quick enthusiasms, flights of fancy, and a kind of weighty wit—irresistible because, like a child, Francis does not take himself seriously.

All of his recent bad luck, so much of it brought down by himself, seems not to have affected him. As though it happened to a person named Francis Coppola, someone sitting right there, but not actually, somehow, the same.

He talks about a South American place he has bought—El Getaway, he calls it. It is really very convenient. “Only a couple of hours from Miami in your plane, got its own airstrip, and it has lakes and waterfalls and the ancient ruins right there on the property. The sea? Oh, it’s close. In a plane we can get there in a couple of minutes, about fifteen of them. Otherwise, it is days of hacking the jungle, of course. We could build this landing strip on the beach. Probably will.”

Probably will. He is like a little boy, living entirely in his imagination with the difference, the great difference, that what Francis imagines always comes true. Both the good and the bad. He will get his airstrip and his planes. But he also got a great disaster, his studio—all because of his imaginatively walking too near the edge.

Hope—that is what it is. And with hope, certainty. Success, failure, but some certainty. And if the latter, then it, too, has its uses. Francis may be up or may be down, but Francis survives. He survives as a child survives. He believes—irony yes, cynicism no. He believes in Francis but, more important, he believes in the world, and still finds it quite wonderful.

8 august 1983. Taken to dinner by Mifune Toshiro at an elegant Akasaka ryotei—fancy food, geisha dances, lively girls to sit beside you and pour. The occasion was the entertainment of Nancy Dowd and John Dark who are here to do her film, R&R, and I had suggested Mifune Productions and introduced Toshiro. Hence my being included.

Mifune is older, has lost some of his hair. His shape has changed but his eyes are the same. And his smile—that wonderful smile, seen so little in the films: charming, genuine, disarming.

The smile is little seen because it does not fit his solemn machismo screen persona. It does not suit it because it is boyish. And it is the boyishness of Mifune, now well over sixty, which so charms. That and his almost adolescent-seeming self-deprecation. Whether this is genuine or not, I do not know. But I do see that he makes very little use of it. He has nothing to gain from it but more charm, and he is already exuding that. No, I think Mifune has an enchantingly poor opinion of himself.

Certainly the pattern of his life is that of a man who doubts himself. The period with Kurosawa in which he allowed himself to be molded, then the number of failures which followed: as director, as husband, as businessman, and even as actor, since left to himself he plays roles like that in Shogun. Mifune always strikes me as ready for failure but attempting, gamely, to avoid it.

He is charming at the party. Nancy is quite swept away, not only with him, but also with her first glimpse at high-powered Japanese entertaining—the food, the drink, and the concern. The kimonoed young lady and I have a perfectly proper conversation about underwear, what is worn under the kimono. She wears no panties, as is common nowadays. It ruins the line of the kimono. So she does not—except, she reminds me, once a month, then smiles charmingly. Mifune, it turns out always wore something like BVD’s under everything, armor and all. The geisha dancer wears only a sheath of cloth under her kimono. Hers is red because she is an entertainer. The other girls’ were pink or, if older, white. Nancy rolls her eyes deliriously when I translate all of this.

Mifune is much at home in this milieu. I have long thought that he might be a bit prudish. Perhaps he is. Here, however, such talk is not considered anything but proper. It has the right light touch. One is not interested and not uninterested, and this is proper. Mifune has learned to be very good at this. And he never goes too far.

Then he makes a speech, a charming one. I am the peg on which he hangs it: our long acquaintanceship, and now my introducing these splendid people. His poor attempts at entertainment and, he hopes, their understanding. . . .

Actually, Mifune Productions would very much like the business and promises to do well. But not a word of that. Fortunately John and Nancy already know how Japan works, and they are now capable of appreciating nuances and subtleties that would have left them blind in London and L.A. Then John makes just the proper speech, almost committing himself, but not quite. Then Nancy talks, properly, to the point. Then I, as is my role, bow and thank and indicate that the happy evening is over.

How well the Japanese do this. The sordid necessaries of heavy financial encounters turn butterfly-like during these light and so personal-seeming encounters. And the sincerity is quite there—so far as it goes. It is this that so completely undoes the West.

I wonder how many parties like this Mifune has a week. More than a few, I would imagine. If he tires of them there is no indication. There he is, boyish as always, smiling as broadly as he did decades ago. Only occasionally, when he thinks no one is looking, or when he forgets, does the smile relax; he will look someplace, the corner of the room perhaps, and there is the inward gaze of a man looking into himself, seeing nothing outside. Of what is he thinking then, I wonder. Of himself? Of life?

Then, with that smile he turns, sake bottle in hand, to pour you another drink, to clown his way through a story, to listen with absolute intentness to whatever it is that you are saying.

Mifune the good guy, the straight arrow. It is all real, it is all there. It is all on the surface, too. Is there anything more than surface? Well, that is not a question profitably to be asked in Japan, where the ostensible is always the real, where there is nothing more.

And yet. Inside are the bandit, the samurai, the shogun, the gambler, the shoe magnate, and Red Beard himself. How can so consummate an actor be only this? But there I have my answer. By being this, he is a consummate actor.

14 august 1983. The Fukagawa Tomioka Hachiman Festival, held every three years: an enormously long procession of omikoshi, the large cross-beamed floats carried on the shoulders of the participants, in the center the ornate house of the god, bells, the golden phoenix atop. Fifty of these floats, each supported by a hundred near-naked men—fifty under the beams chanting and dancing, the other fifty waiting to take their turn, dancing alongside. Each float is from a different section of Fukagawa, and so the half-kimonos, originally worn but shortly discarded, carry the quarter’s name and its mon of a distinctive color. In fifty years, Fukagawa, completely destroyed by firebombs in 1945, has been rebuilt. Fifty floats, each with at least a hundred men—five thousand, and five times that number lining the streets, watching.

A spectacular festival—its size, the number of people involved, that it is so uninhibited, and that so much flesh is so casually displayed. Also, that it is held in the heat of summer, on a day traditionally the hottest. Hence the shed clothing, the sweat, the reddened, sun-tinged flesh.

Hence also the water. It has for hundreds of years been customary for the houses along the way to have buckets of water, or hoses, or water pumps—all ready for the passing shoulder-carried, hundred-legged floats. Streams of water curl into the air, water flung hangs before it descends. From all sides, all at once, continually—water descending. The nearly naked men are drenched.

Most are wearing only a tucked-in loincloth. Their drenched hair begins to steam in the sun; water runs down arms and legs, puddles, and evaporates. The humidity around the floats rises as the water turns to steam. The loincloths, white cotton, turn transparent as the water courses. The god appears.

Fertility is what this festival, like most, is about. The jostled god in his dark little box atop the float is a fertility god, and he thinks only of procreation and the things that allow it: heat, water, and movement.

The men wear their nakedness as though it were a costume. No one jokes or laughs, and no one stares as the loincloths turn transparent and the jostling dance continues.

This spectacle is deeply erotic because it is not concerned with actualities, but with possibilities. Like the blossom hidden in the bud, eroticism lies always in the future. These small and visible gods are not, after all, standing erect. They are merely there, made visible by the magic of the festival—fertility promised.

With rhythmic shouts, one float after another sways down between the lines of spectators. The procession takes two hours to pass. Two hours of naked thighs and barely masked loins, pounding buttocks, strained shoulders, and faces turned skyward, chanting the rhythmic cry of the matsuri. A spectacle—something from Japan’s past, and something with us yet.

27 august 1983. Tonight I went again to Sumida Park. There is a grove on a hill, a still lake, paths that wind and rejoin. It is dark; a few street lamps cast pools and the stars are bright beyond the tracery of leaves.

The dark park, night—and I again relive my oldest dream. It occurred, several times it now seems, over half a century later. I was very young—six maybe. A park, perhaps, or a woods, and it was dark, late, and I was there alone. And from the shadows walked a man. I remember the man’s strong face, half in the shadow, and the soft touch of his hard hand. And the look he gave me in the half-light, loving, protective, when he told me not to fear, that he would take care of me. I turned in my dream and buried my face, and his chest was hard against my cheek. Then I woke up.

But did I? Here I am again in the dark in a park, and I am now near sixty. The intervening years have seen many dark parks and, living my dream, many hard men. Each I have pressed my head against.

I am looking for the original, for the man in the dream, you will say. Well, yes. But when you have found him hundreds of times and still go on looking, for what then are you searching? If you have not found him by now, you never will. Or, conversely, if you find him every day, you may be certain that he does exist only in dreams.

What was it he said? Yes, that he would take care of me, look after me, that I would no longer be alone. Though I am sixty now, no longer six, they—he—are still the same age, twenty-something. They, the inhabitants of the dream, have not aged—the same strong face, the same hard hands.

Sometimes I, an adult, have turned these strong men again into boys, and it is I who have looked after them, taken care of them. But in the dark I am again the child, and it is they who are adult. What could it all mean? Anything? Nothing? No, if only because things cause other things, there is probably a meaning—but it is not one with which I am concerned as I watch the shadows in the darkened park.

Each new man—he is the answer. It is he whom I first saw over half a century now past. It never is, to be sure, but I am always there waiting. I surmise my reason. I am entertaining—yes, that is the word—entertaining hope. Something that affirming, that health-giving. I stand in the dark, calm, assured, faithful, hoping.

25 november 1983. Dinner with Paul Schrader and Mary Beth Hurt. He is having some difficulties. Yoko, Mishima’s widow, has had second thoughts now that she has signed the contract and taken the money. For some time she has been cleaning up after her husband—suppressing his film Yukoku, [Patriotism], cutting off his ex-friends, denying things—in order to make him into the man she thinks he ought to have been. Now she sees that Paul wants to make a film about Mishima as he was. Very tempestuous luncheon the other day—tears, I understand.

The main problem is Mishima’s homosexuality. She, who should know it best, is now denying it. Paul wants to include a part of it since he could not well leave it out. Tears, because their daughter somehow got hold of a copy of the script and was instantly devastated. The reason was not the strength of the script, but that the daughter had been uneducated as to just what her father was like. A slight reference in script to a gay bar. Stunned daughter. The son several years ago read the masturbation scene in his father’s Confessions of a Mask. Trauma. Was Dad really like that?

I doubt this is true. Impossible to tell how much accuracy remains in all this, because it comes strained through the mother’s rendition, then Francis’s, then Paul’s. Also, because Yoko is so playing her role. Still, it is probably true that she has kept the kids in ignorance. Part of her plan—perhaps part of her revenge as well. I remember her as a neglected bride. She had to live with the monster. It is now that she has her way, and in so doing chooses to geld him.

It comes as no surprise to learn that Yoko particularly did not want Paul to see me. I know too much. Also, I am not on her side because I have been known to criticize the illustrious and now sainted author. Last time I saw her she smiled and said that I was just not to be trusted. That is perfectly true. But I knew Mishima as well, and I want to have no part in what she is doing to him now that he is helplessly dead.

2 march 1984. The opening of the Isamu Noguchi show at the Sogetsu Kaikan, in the indoor terraced stone garden that he himself designed for the building. Isamu there, brown, leathery, now nearly eighty, dressed in his Santa Fe best—big silver turquoise-studded belt. Though Japanese, he is very American, having been educated there, having lived there most of his life. He looks like Georgia O’Keefe now.

He has also gone into multiples—which is very American of him. The new work (hot-dipped galvanized steel) comes in editions, of eighteen or twenty-six. At the show was one of each, all twenty-six of them. One is encouraged to buy, or will be. The prices are not listed at the opening, however. Soft sell.

The pieces themselves are very Noguchi. They look as if made of silver cardboard, and fit into each other—their various parts have slits, like packing cases. The forms are “free,” kidney-shaped. A slight flavor of the Orpheus props. I cannot imagine anyone wanting one.

Here in the antiseptic Sogetsu interior—done by Tange, all of whose interiors are like the insides of iceboxes with the lights left on—they seem unimpressive. Perhaps in a garden, a real one, they would fare better.

But then Isamu has always talked better art than he made. He is inspiring to listen to, particularly when he starts on Japanese garden aesthetics. But then from all this comes the work, which is sort of preschool. And now we have these multi-copy prefab kindergarten objects.

Isamu very much in his element at the party. Lots of famous people. Teshigara Hiroshi, lion-maned and sleek, melts into the background discreetly taking pictures, determined that this is Isamu’s show and he will not, absolutely will not intrude. That clown Okamoto Taro, whom some perhaps still regard as an artist, here but subdued—though certainly not from modesty and a desire to defer to Isamu. Maybe he is still feeling the death of Miro, the man from whom he took his style. Kamekura the designer, some TV and screen folk, and a few favored foreigners. Not the beautiful people—they go to Issey Miyake’s—but the in-people. And there are no models, though there are two white American shakuhachi players.

12 august 1984. With Eric to the last performance of the final annual obon exhibition of Japanese folk festivals, held at the grounds of the Meiji Shrine. About ten thousand attended and five thousand, it seemed, performed.

Other countries may show their festivals en masse like this—I remember a Moroccan festiva in Marrakesh, and a Yugoslavian showing at Dubrovnik of dances from all its provinces—but only in Japan would these be uncommercialized, by amateurs, by people from the provinces themselves. And only, I think, in Japan, with such vigor and enthusiasm.

Things I remember from this final evening: The platform in the center suddenly invaded by dozens of young men in breechclouts waving enormous ship’s flags, followed by a hundred or so young women in fishing wear, surrounded then by others in sea-blue kimono, and the drums and flutes and bells and voices doing the wonderful Tairyo Bushi. Then, at the last verse, those circling about suddenly produce long strips of blue cloth that are waved to simulate the sea.

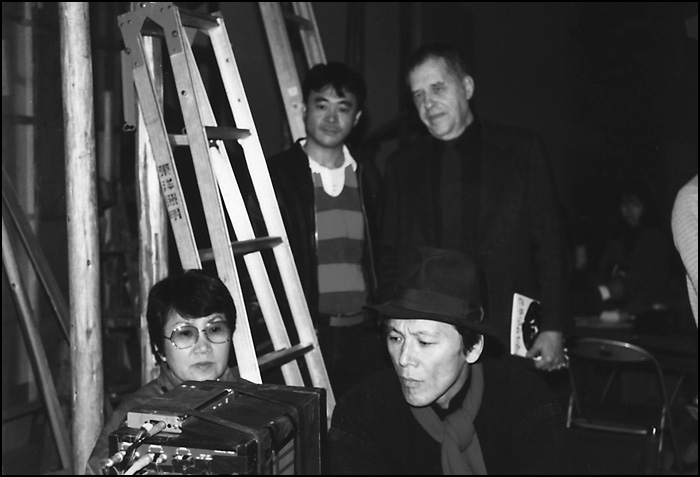

The Kyogen Monkey-Skin Quiver, Nomura Troupe. Last row center: Lincoln Kirstein, Meredith Weatherby, Richie. nomura mansaku

Eight enormous floats from Shikoku, each fifty feet in height, held aloft and moved about by masses of young men from the island’s provinces. A mock fight, like galleons on a sea of people, and an obeisance to the audience, like a herd of trained elephants.

A huge illuminated portable shrine from Akita that, held aloft by dozens beneath, floated like an apparition across the crowds, the lights inside illuminating every tracery.

Fireworks, enormous ones, from Hyogo, each held by a young man, a row of them clasping these roman candles like kegs. The fire sprayed past their faces and drowned them in a burning rain. They stood there, rows of them, like fiery caryatids.

A giant lion from Kobe: The head fifteen feet high, the cloth body manipulated by one hundred fifty men inside with long poles, pulled by a hundred more outside—a lion circus tent.

The Nebuta from Aomori: First a phalanx of dozens of drums, held in threes and pounded at the same time. Then a group of dancers, all girls. Then the big drums, on wheels, each hammered by five strong men. Then young men in loincloths, leaping and capering. Then the mighty illuminated float, fifty feet high, a hundred across, illuminated from the inside—a giant samurai, sword aloft. And following this, the people from Aomori all dancing and leaping. All of this began at five-thirty as the sun was setting, and ended at nine-thirty as the full moon was rising. A marvelous spectacle, and the last. It now simply costs too much. The committee has had to give it up.

13 august 1984. Thinking of visual spectacles today, the great ones I have seen. To be sure the Grand Canyon and Ryoanji are both visual spectacles and I have seen them both, but that is not what I mean. I mean man-made ones. Let me see:

When the curtain opened on the first night of Tudor’s Romeo and Juliet and the Met audience saw the Berman set against that great blue cyclorama, that gasp of surprise and pleasure. Then Sir Thomas Beecham raised his baton and the Delius began.

In the Kabuki Ibaraki, a charming little dance for the page, all nautical references (pulling the oars, riding the waves) with the precision of nineteenth-century clockwork. Then, three comic dancers in the interlude—Edo street trash in the middle of fifteenth-century Kyoto. In the coda a wonderfully dance-like turn on the samisen, and the gliding exit of the three, legs up high, feet slapping, real high-stepping in a perfect parody of charm.

When the curtain of the second part of the first visit of the Beijing Circus to Tokyo (in the early sixties) went up and revealed a second curtain made entirely of jugglers standing on shoulders, filling the proscenium—all the hands and some of the legs juggling something.

A performance of the Nomura family of the Kyogen Utsubozaru (The Monkey-Skin Quiver), in which the monkey was played by a small child and the ensemble was of a perfection to draw tears.

The Great Black Current Tank at the Okinawa Exposition, where on either side, towering glass walls held the entire black current, simulated, with all of the fish, real, that are in it: shoals of tuna, fleets of dolphin, and armadas of whales, all circling, the ocean towering above.

A performance of Hagoromo in Kanazawa, home of Noh, where the heavenly princess was a masked ninety-year-old man, whose every movement, every gesture, was that of a young, virginal, heavenly creature.

In the movies, lots: like the flight of the arrows in Henry V and its inspiration, the battle on the ice in Alexander Nevsky; the close-ups of the animals in Au hazard, Balthazar; Falconetti’s face in Jeanne; the first glimpse backward over the length of Skull Island where we can see the distant great gate in King Kong.

Again a gap in the journals, this one four years—apparently no journals were compiled during this time. Much else, however, was written: Viewing Film, A Taste of Japan, Tokyo Nights, Introducing Tokyo, and Public People, Private People.

16 may 1988. Met Shulamith [Rubinfein] and Ed [Seidensticker] in front of the statue of Saigo at Ueno, and we went and ate blanched chicken toriwasa and pheasant donburi—though this was probably chicken as well. We are three legs of our four-legged Jane Austen Society (the fourth leg, Sheelagh [Cluny] is always now in London or Canada). After, we walked down Ameyokocho and Shulemith innocently asks what this place name means.

“It means ‘Sweet American,’ that’s what it means,” said Ed. “Ame is the contraction and it is homonymous with ame, the candy. The idea is that the Americans gave candy away after the war.” “Oh, how sweet,” said Shulamith with that girlish giggle she sometimes has. “Not at all,” said Ed. “It is not a proper term. It is derogatory. It is like our calling them Jap for them to call us Ame.”

This leads to other things and at the end of the meal we have not talked much about Jane. Later, over coffee, I wonder (to myself) just which of the characters we have come to resemble: Ed is Mr. Woodhouse with teeth; I fancy myself the witty and heartless Mr. Bennett; Shulamith, well, someone very nice—maybe Elizabeth, grown older and minus Darcy; Sheelagh is Fanny’s brother—hardly ever here.

23 may 1988. Reading Raymond Carver. Never had before. Liking him but suspicious of this. The stories are so laconic that I suspect formula. Have not, however, actually detected any. Certainly, I admire the brevity. As always, successful art inspires. I too want to write such stories, and think of a theme.

A man has a happy relationship based, on his part, on a natural passivity, and this continues on until another person starts a relationship with him. Passivity continues to the exclusion of the first person. Am obviously thinking of me and the sergeant [Kiyota Kazuaki]. A naturally boyish youngest son’s passivity allowed for a relationship that was not natural to him. Yet he drew from it things that sustained him—regard and knowledge. But then he was married, something his passivity also allowed—an arranged marriage that others wanted. And she is perfectly good, his wife. And his passivity extends. He neglects me. Despite knowledge missing, he takes the easy path, stays home. So what I had congratulated myself on discovering, his passivity, becomes at the end something unwelcome. Told this way it doesn’t seem much of a story, but the shape is nice. I turn it this way and that, admiring its symmetry. I think, however, I will have the story told by a woman. Will make the homo into non-marriage, make the non-homo into marriage. Can allow myself a bit of sentiment that way. [It became the short story “Arrangements.”]

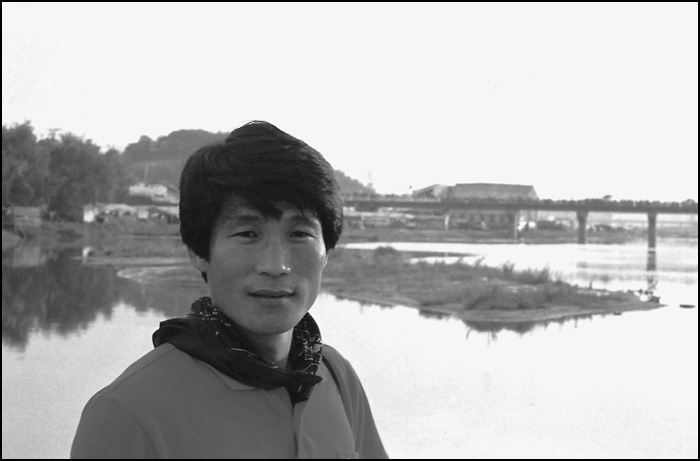

25 may 1988. Itami Juzo, famous director son of a famous director father. “Cut!” shouts Itami into his lapel mike, after the eighth take of the final scene of the second part of A Taxing Woman [Marusa no Onna]. He is wearing his black Chinese shirt, his slippers, his red scarf, his black fedora—emblems as necessary to image as is the constant cigarette, the continual cups of coffee, the hard candy he nibbles during shooting.

The script assistant confirms that this final scene consisted of six rehearsals and eight takes. “The first,” says Itami, “was probably all right but I wanted to take one more to make sure and ended up doing eight. But that last one was all right too, I think.” She agrees.

“Wasn’t very economical though, was it?” he asks. Then, to me, “Money, money. So I work fast. This picture only took me fifty-four days. You save a lot of money that way.”

Making money, that’s one reason for making films. And saving money. “That’s the reason I star my wife in all my films. Want all the profits to stay in the family.”

With Itami Juzo (in hat), 1988. newsweek

Making money is important. After all, Itami had had to mortgage everything he owned to make his first picture, The Funeral. He said, “I read that I would even have mortgaged my wife, had the banks wanted her.”

The picture was successful, however, made money, and so he decided to become a full-time director. He hadn’t always wanted to, however. He’d been an industrial illustrator, an essayist, a translator, a talk-show host, and an actor. It was only when he turned fifty that he became a director—like his father.

Itami Mansaku was one of Japan’s most respected prewar directors, an innovative man who helped turn the Japanese period film into the humanistic expression that it for a short period became. In this he inspired an entire generation of postwar directors—Kurosawa Akira, Kobayashi Masaki, Uchida Tomu. He universalized the specifically Japanese, and in doing so he created films that were art.

He died when his son, Juzo, was thirteen. Left fatherless, raised by a mother of whom he later said “had no ability to bring up children,” he moved from one profession to another. “I think I am about twenty years behind my generation,” he somewhere wrote.

Becoming a director like his father brought him up to date. Though well known as an essayist and an actor, he was suddenly the film maker who had revived the movies in Japan. One of the first things he did with his newly earned money was to restore one of his father’s films, the 1936 Kakita Akanashi.

Then he began consolidating his profession—making plans, making money. You had to make the audience want to come to the theater if you were going to show a profit. Making gentle fun of them, as in The Funeral and Tampopo, was one way.

This is because, as he explained, the viewer needs a surrogate; just as a child needs someone from outside the family to fully mature. What it needs is someone to dispute the family view and show another opinion.

He crunches a piece of hard candy. And this time, he says, in reference to the film he is now completing, the tax people don’t get the money. This is because the hero, the wily leader of one of Japan’s many new religions, has had all his illegal gold cast into Buddhist altar implements. The final scene shows him in his crypt, taunting the impotent tax officials.

“And all in just fifty-four days,” he says. He can work so fast because of his system. While other directors are roaming the set and peering through the viewfinder, Itami sits quietly in the director’s chair and looks into a television monitor, giving instructions through his lapel mike. This way, he says, he stays out of everyone’s way and still, since the television camera looks directly through the camera’s lens, can see everything the cameraman can. Handy, too, on a small set.

I peer inside. The gold-filled crypt is very small. The camera hung inside can be rotated. Inside too were the two actors—the hero and his pregnant girlfriend, and the cameraman—outside was the director. The scene on the small monitor was properly claustrophobic as the same actions were performed eight times.

Mikuni Rentaro, the head of the cult, had gleefully whipped off the covers, laughing maniacally, and displayed the gold. The pregnant girlfriend had reacted. Four times he flubbed his lines and once the camera ran out of film.

Itami did not lose his temper, nor even raise his voice. He crunched more candy. Smiling he turned me and said, “Stress.” The reference was to when we had worked together on the English subtitles for The Funeral and he had first learned the meaning of the word—from me.

He had questioned every line of my work. And though he knows English, I know it better. “Now here you wrote ‘for,’ ” he said, “but that is a preposition and prepositions are tricky. Wouldn’t it be better if you had written ‘to’? That’s another preposition.” All of this was in Japanese since, no matter how well he might think he knows English, he never uses it with a foreigner. The reference to stress was my outraged reaction to this.

The scripter shook her head. She thought he was referring to himself, and Itami was never stressed. Not at all like Kurosawa, or that monument to impatience, Mizoguchi Kenji. Nor much like his father.

26 september 1988. Rain, more, again. This month has had one day of sunshine. The rest range from sprinkles to downpours. The Japanese, always prone to speak of the weather, usually with approval, are perturbed—and suspicious. Did we do this? We, with our exhausts, our chemicals, our hair spray? This, coupled with the discomfort. Walls sweating in the subway, niter in the passages, hot wet winds. We perspire under our umbrellas, and moths fly out of the closet. I find cockroaches in my sitting room. Usually only a few in the kitchen. A lady on the subway begins to complain even to me, “. . . and the backs fell, positively fell, right off my books.” “And my piano is coming unglued,” said a wet lady across the way. It is sure catastrophe when strangers start speaking to each other.

28 september 1988. I always work on my own things in the morning, labor at making a living in the afternoon, and meet people or play in the evening. Day after day after day. Never get tired of it because each day is different, though the timings are about the same. Awake at seven, coffee, newspaper. Then shower and at work at desk by nine or before: right now it is the Oxford book on Japanese film. By noon, tired of this and lunch, in or out. Then making a living. Go to International House or go to Sogetsu, or go see films to do subtitles for, or go to the library to research an article. This can go on to six. Then I meet my friends, or go about looking for new ones. Usually home by eleven. Always in bed by twelve. Today was no different from other days.

29 september 1988. Party. I am recognized. “Oh, aren’t you . . . ?” “Yes, I am and who are you?” “Oh, no . . .” and then, “I just heard your lecture . . .” or, “I saw your picture in the paper . . .” or, “I saw your photo on the book jacket . . .” Why do none of these encounters ever turn into anything? I am ready. If people know who I am and come up and talk, they already know something about me. I like fame if this is what it is.

But, I would not like it if it got as large and dangerous as I saw it with poor Mishima, who used to have to cross streets to avoid crowds, or Kuroyanagi [Tetsuko], who gets quite nervous as people surround her on the street, smiling, well intentioned, but big, surrounding bodies nonetheless. I would not like that. But a few people here and there. . . .

Yet, they always leave me. I never leave them. I suppose they do not want to presume. I wish they would. We would have lots to talk about. Me.

1 october 1988. No, Japan has changed. What I thought never would—one of the reasons for spending my old age here—is gone, never to return. This is the possibility of meeting a stranger and making a friend. Right there, right then. Forever. Oh, meeting strangers is possible enough. Indeed all friends are initially strangers. But it is no longer possible to enter into that sudden intimacy that was once so much a part of the charm. The reason is that the attitude toward me, toward any foreigner, has changed.

It is because we are not needed any more. No one has any use for us. They do not see trips abroad in our eyes. These trips are something they can themselves afford. And there are so many of us. We have become common. And since Japan is rich now and the other countries are not, they need not imitate us.

I am speaking of my regretting imperialism, I know. I ought to rejoice that Japan is no longer subject to it, but I do not want to. It was too much fun being treated as someone quite special. And one no longer is. A foreign friend in speaking of this says, “Why, we might as well be living at home.” I smile because it is amusing. Not he, he takes it seriously. Then looks for reasons. It is because he is getting old. Or it is because of fear of AIDS, which, of course, comes from foreign lands. But, it is not that. It is that the Japanese have outgrown us.

2 october 1988. Sunday, a soft rain, but cooler now. Shinjuku, the streets shining, reflected umbrellas: pink, mauve, chartreuse—people in for the day. Country Japanese are fond of untoward colors. I see a boy with geranium-colored trousers. Day-tripping workmen often wear purple cummerbunds. Against the gray rainy cityscape these subtle colors shine and shimmer.

At Isetan I watch the quiet crowds. How well dressed everyone is now. More, how stylish. Not just the spikes and slashes of the young. Everyone else displays a kind of good taste—solid materials, well cut—the kind of taste you see in the Edo street scenes of Hokusai. Solid, plain, well-cut kimonos. Splashes of color here and there. And, I notice, as in the Hokusai, no faces. Is this because Japanese in crowds have never have had any? No, it is because in crowds we all have a kind of “faceless” expression. The face is there but it is not expressed. This is something Hokusai knew. One sees Japanese faces only when people are alone or where they are somewhere where they know each other.

3 october 1988. A good long time now. He lies there in the center of the city, dying. Very old, very strong. Whoever would have thought that that skinny old man would be such a laster? And last he does, day after day—his doctors pumping blood into him as fast as it leaks out.

Hirohito has not a secret left. We not only know all about the rectal discharges, we even know their temperatures. An avid audience of about one hundred million people take in the enormous amount of information the media churns out—important TV broadcasts are interrupted to give us the latest non-news.

There are in addition hundreds who kneel in the drizzle in front of the gates of the Imperial Palace. They will probably catch their deaths themselves. And thousands who line up with umbrellas to sign the condolence books. I look at the line of colored umbrellas, which I see from the Press Club twenty floors high: a distant rainbow-tinted caterpillar in the drizzle.

There is some criticism of all this coverage. No private citizen, no other person, would be given it. And does this not mean some suspicious reversion to prewar thoughts? The Emperor is not a god. Why is he now treated as one? Right-wing militarism on its way back? Some think so. Leftist students are giving speeches at Ochanomizu Station. They warn of this. They do not want the right to overcome. They want the left to overcome.

I think the reason for this distasteful and massive public display of a single death is that for anyone over forty, the Emperor’s life is bound up with their own. One mourns for lost youth as well. Another is that many Japanese always do the same thing at the same time, and it is an unusual person who will stand out against one of these mass movements.

Yet there are many such unusual people now. Not one person to whom I talk about the dying Emperor thinks proper the massive attention paid. Nor is anyone, including many of my contemporaries, upset by the coming death. Many make jokes. However, my friends are not arch-traditionalists or else they would not be my friends, so this probably proves little.

It suits many purposes, this crisis. The Diet uses it as excuse not to work. Major companies use it as excuse to avoid doing things they do not want to. Chiyonofuji, traditional sumo star, cancels a party out of deference. Itsuki Hiroshi, singer, cancels a wedding—but he is of Korean ancestry and so probably thought it safer to. Lots of cancellations. No fireworks here, no garden party there. I talked with someone on the phone who wanted me to write an article, and I said yes, but then she said, “Well, we haven’t quite decided, there is this unfortunate Emperor thing.” So even magazines are thinking what to print. Nothing too inflammatory, nothing too frivolous, nothing too foreign.

Me, I think this kind of mindlessness is as deplorable as it is human. I dislike any kind of joining—the Catholic Church, the Soka Gakkai, the Communist Party, or kneeling and praying for HIH. In my ideal world no one would pledge allegiance to anything.

I also notice a certain attitude. People sigh a lot. It is as though the Emperor is showing a lack of tact, of good taste, in being so long about it. Nonetheless I dread the days after the death. Certainly full national mourning—all for this frail, limited, stubborn little man. On the other hand I too can get a cheap thrill out of it. The longest reign in recorded history is about to end.

4 october 1988. Walking down the street to International House—that annual odor. I remember the first time, many years ago. Since the street runs along a schoolyard I thought that bulging cesspools had overflowed, not stopping to consider that cesspools are long gone from central Tokyo. Then I noticed the squashed yellow splotches—crushed ginkgo nuts, and overhead a great yellow leafed ginkgo tree. I make a kind of haiku:

Oh the smell of shit. Ah, autumn is once more here.

Why should the fruit smell of excrement? If it were spring and the blossoms smelled that way I could understand. It would attract the bugs and fertilize the tree. But in deep autumn there are no bugs about. And in the spring the smell of the blossoms is that of semen. What kind of tree is this?—semen in the spring, shit in the fall.

I remember the first time I was aware of the springtime smell. It was 1947 and I was in the courtyard of Engakuji in Kita-Kamakura, with Gene Langston, and we were spending the night at Dr. Suzuki’s guest house, and Gene suddenly stopped, his nostrils twitching: “Amazing—it smells just like semen.” And so it did.

5 october 1988. Someone—who, Balzac?—said a man’s character is to be disclosed by his library. Very well, let’s see. In mine: the complete Jane Austen in the Folger Edition; all three novels of Lewis Carroll; all the poetry and a biography of Cavafy; all the short works of Kafka but none of the novels; some Henri Michaux, including A Barbarian in Asia; Jules and Jim; everything of Nagai Kafu in English; lots of Colette; historical fiction of Ibuse; short works of Naoya Shiga; Cocteau, all of the novels; everything in English of Borges; Sartre’s biographical writings; Isherwood’s Berlin Stories; collected Auden; collected Dylan Thomas stories; complete novels of Henry Green; lots of Marguerite Yourcenar (everything in English); lots of Susan Sontag; complete poems and prose of Elizabeth Bishop; Sleepless Nights of Elizabeth Hardwick; everything of Jimmy Merrill, etc. And that is only the fiction-poetry part.

There is a section given over to books on Japan including all my reference works. And a whole stack of film books, including my own. Space is a problem. I have to get rid of things. Recently exiled the Bible and the complete Shakespeare—on the shelves for decades and never read. But not thrown out. I am too sentimental (and superstitious) for that. Both from my mother—one (the Bible), nearly half a century ago. I keep them on a shelf with other discards. Not the shelf in the entryway however. Those discards are for people to pick up and carry home.

16 october 1988. Sunday. To the Kabuki with Eric. Some modern trash, and two classical dances. One of them is Yasuna with Baiko. Though a “national treasure,” Baiko still looks like a lady searching for a golf ball. In the other, Sagimusume, Jakuemon, his face often under the knife, looks odd but then he is supposed to be someone half a bird. But the hoyden way he carries on is not nearly elegant enough for this dance.

The interesting play was Moritsuna Jinya, the single act surviving of a much, much longer work and now a “Kabuki classic.” As I watched its reprehensible story of a man quite cheerfully sacrificing his little boy, killing him because of loyalty to the lord, I was again struck by how wonderfully acted it all was. Takao as Moritsuna was immaculate. When he identified the (wrong) severed head he went through the canon of twelve emotions. And it was all there. It was like a great violinist. The violinist is only doing Paganini to be sure. And I realized that one of the most moving and touching things about Kabuki is that this talent is lovingly squandered on junk.

There is, however, a difference. Even Verdi and a clutch of fine singers cannot make one sympathize with poor Gilda. But at the Kabuki there were sniffles as the little boy spilled his guts and kept right on piping (children’s Kabuki lines are all on one note—like the oboe sounding its A, for hours) and took as long to die as Camille. But people believed, for a time at any rate. I didn’t, but I too was moved, though in a different way. This presentation of emotions (rather than the representation of them) was moving as a fine carpenter or master stone carver at work is moving. I am moved by the artistry of how the thing is done, not by the thing itself.

18 october 1988. Gave a talk at the Press Club. Talked about “Being a Foreigner” and was listened to by a hundred or so of different nationalities and a few races. Many Japanese. I have talked in public for so many years now that I can tell what people will take and what not, what they will laugh at, what they will shake their heads over, or nod at. And, finally, I know how to be evangelical. Christ lost a good witness when he lost me.

But do I believe any of what I say? I do at the time, I know that. It seems such a good idea. But in the early morning hours when I wake, wake with such doubts that it awakens me, then I do not believe any of it. My heart beats like something trying to get out, and I am certain of nothing. Yet just hours before, there I was, certain of everything.

19 october 1988. Sitting here all wired up. Electrodes various places on my chest, wires running into a tape recorder I must carry on a strap over my shoulder, complete with a special large switch on a separate wire that I must push to punctuate the tape when I “feel funny”—doctor’s term, chotto okashiku nareba. Have not felt funny once. Having the machine on has obviously inhibited the unruly organ. Actually, the only time it ever really acted up was five years ago, when it leaped for hours like a frantic fish—a frantic frozen fish, for my chest was as though filled with crushed ice. This I thought, is angina pectoris. And so it was—my first and so far last. Still, routine tests have located something okashii going on. Hence the wire-job. Had it five years ago and felt funny wearing it, everyone stared so. Now, half a decade of handbags, shoulder bags, earphones, and straps have intervened. I walk about today and no one notices, except an acquaintance at the porno where I had gone to stimulate the organ. And he says, “Hey, what a cute little tape walkman you got there. . . .”

From now on Richie no longer used his journals as sources for other works and became more interested in them for themselves. They began to have a purpose all of their own. One of the reasons was that he was himself experiencing life in a more intense way—time was passing; friends were dying. The evanescence of which he had often spoken was now apparent. He thus wanted more than ever to leave some account of what things (including himself) had been like. This led both to a closer observance of the world outside, and to a deeper, more frank investigation of himself and his motives.

12 may 1989. To see Bando Tamasaburo at the Embujo in an Ariyoshi adaptation, Furu Amerika ni Sode wa Nurasaji. It is Shinpa, but a comedy: Osono works in a Yokohama brothel: it is 1861 so the girls are divided between those for Japanese and those for foreigners, and one of the “Japanese” is claimed by a foreigner—so she kills herself. This at least is the story put out. People praised, anti-foreign ronin come to marvel; Osono becomes something of a priestess in this new cult but eventually goes too far and the entire edifice collapses.

Tamasaburo plays Osono in a cool, big sister manner, half tough mizushobai mama, half whore with a heart of gold. A performance, always hovering on the edge of camp, never falling over. Playing the cynical “priestess,” he is at his best, in complete control until he comically loses it and must then retreat into “femininity.” He knowingly impersonates that male invention and does it so well that he shows only those seams he wants to show.

Afterward I am taken backstage to call. He is in his mauve dressing gown, looking strangely Nell Gwyn—it is the decollete. All makeup off, he also has a scrubbed, very young look about him. “It isn’t really Shinpa, you know. I don’t think you’d like Shinpa—too weepy. This is a comedy.” Talking on about Shinpa, with which he alternates Kabuki, he spoke of Izumi Kyoka and wondered why the West was not more familiar with him. I said it was true, they only knew Taki no Shiraito thanks to Mizoguchi, and Demon Pond thanks to Tamasaburo. “Well, they ought to know more. Look, people know Tanizaki and Kawabata. Why not Izumi.” Why not indeed, we all wondered.

Tamasaburo is, like many actors, concerned to make an impression of seriousness. He wants to talk about ideas, as though to prove he is capable of them. At the same time it is impossible for him to hide a frivolous charm. This showed in a small contretemps at the beginning.

He had asked about my small role in Teshigahara’s film Rikyu, of which he had heard. Then, with no transition, asked, “First time?” I, not unnaturally, thought we were speaking about me. “And not very good,” I said. At which he gave a high, infectious laugh, and looked at me with apparent amusement. Then I realized that he meant was it my first time at Shinpa. Straightened out, the conversation continued but I had had a glimpse into the charm of an actor whose instant reaction was to disarm with laughter.

I sat on the fake Louis XVI petit point until the conversation stopped for a second and then, before it began again, stood up and thanked him. That is the way to behave in the green room. Otherwise the host becomes one’s captive. Then, for the first time, he became effeminate, the good hostess seeing off her guests. Life is made of such roles—most men are male at hello and their mothers at goodbye.

14 may 1989. Go to get a haircut. My barbershop, the Ogawa in Shinjuku’s “My City,” is expensive enough that it is grand. Boys in attendance to bring things and take them away at a gesture from the head barber. Barbers calling each other sensei, flourishing with hot towels, or in convergence over a difficult head of hair.