In addition to the journals, Richie was writing Tokyo: A View of the City and doing a final editing of Kumagai (Memoirs of the Warrior Kumagai), to be published in 1999. He was no longer mining his journals for material for other works. At the same time, he was now editing them as he wrote them. Thus, only Richie knows what originally filled the chronological blanks.

7 january 1999. Kinoshita [Keisuke, film director] died on the last day of the old year. I did not go to the wake or the funeral, but I did sit down and think about him. A smallish, dapper man, demanding and sentimental at the same time. An air of undefined unhappiness about him, which made it easier to understand why he so threw himself into work. No family except that which he created on the set—his unit. Takamine Hideko, Matsuyama Zenzo. He married them to each other as though they were his children. Sada Keiji, Okada Mariko, other Shochiku actors—the family, the only family. All of those placid films about adolescents, usually boys, and then, like mountaintops, the peaks of a few films—Twenty-four Eyes, and others.

I remember once showing him a film of mine. Perhaps it was Dead Youth. He watched it almost greedily, but by the time the lights were turned on he had already pursed his lips and was shaking his head. Later he told someone (who told me) that he had been shocked, so shocked. Such a vulnerable man he was. And such a long death, well over a decade in that apartment in Aoyama. Today a card from Max [Tessier] about this death, and wondering who might be next.

13 january 1999. I am reading the journals of Ozu. They have been translated and Catherine Lupton sent me a copy. Translated into French, which makes for a certain oddness—Ozu’s expostulating: “Zut alors!” They are curious in other ways as well. I cannot imagine why he kept them. Each entry reads like a social calendar, though it may also include the weather, how he felt, and what he ate. Certainly what he saw—he went to the films every other day. Rarely did he indicate how they struck him. Only occasionally—nothing extraordinary about La Kermesse Heroïque, not too impressed by All About Eve.

But he knew everyone, and saw everyone all the time. Many entries about being with Shiga Naoya, being with Takamine Hideko. Among the directors he apparently socialized most with were Shimizu Hiroshi and Uchida Tomu. And every night a dinner or a party or a bar. Bars with names like Florida and Candy, geisha houses, hotels. And lots of drinking. “Tonight, again, I overdid it. Upset stomach.”

31 january 1999. I went to a memorial concert for Hayasaka Fumio, through whom I first entered the Japanese film world. They played first an early work, the 1937 Ancient Dance, a bit like Gagaku, something like the later score for Rashomon. At the end they played his last work, the 1955 Yukara, a suite based on Ainu folklore: strong, personal, dissonant, raw—a kind of Sacre from the far north. Takemitsu told me once how he cried when he first heard it—for the music but also for his dead teacher, Hayasaka.

In between, the 1948 Piano Concerto. I had heard it at its premiere. I was sitting in Hibiya Hall, and there was my friend smiling and bowing from the stage. I now wondered what I would remember of it, as I had not heard it since. Nothing of the rhapsodic opening lento was familiar, but when the rondo started—oh, of course, how could I have ever forgotten it? An engaging pentatonic tune that went through its possible permutations with assurance and charm, and always landed on its feet. And as I listened I relived my five-decade-old delight. It was like meeting Hayasaka again.

1 february 1999. I talk about the Occupation, a panel with only me and Nishiyama Sen on it, a “Luncheon Discussion,” as the Press Club calls these things. Afterward, questions. I am asked to account for films, and Sen is asked to account for Reischauer. “Was it not true,” asked Sam Jameson, “that you were to make a mistake or two in translation so that Reischauer could publicly correct you and hence know more Japanese than even a Japanese?” Sen denies this.

2 february 1999. I buy a plastic shopping bag to carry home groceries and on it is written: “Knowing—where you’re blowing getting to where—you should be going—Golden rain—bring you riches all the good things—you deserve now. Find your way out of Silent Forest.”

Opening up a Lotte Choco Bouchée, I read: “Confidence of creating deliciousness. This tastiness can not be carried even by both hands.” Slowly chewing, I meditate upon this strange culture that makes so free with mine. Such English as this affects them only as something pleasantly modern, but it makes me believe that I am living in a world where behind every object—a shopping bag, a chocolate cookie—lies paranoia, madness, violence, and death.

12 february 1999. Took Karel to lunch. He says that Japan’s only way out of its dilemma is through some kind of revolt that would stop the machine, overturn the bureaucracy, but that he could not imagine it happening. I told him that Nagisa Oshima had said that this had occurred only three times in Japan’s history: the Tempo Reforms, the beginning of Meiji, and in 1945. And each time the structure re-crystallized, and petrified. We agree that there are no villains, no tyrants; the problem is structural: this model no longer works in 1999.

17 february 1999. The Hanis, Susumu and Kimiko, take me out to lunch, a new French restaurant specializing in fish. This is in return for my having designed his retrospective and gotten it on the road—where it still is, showing in Toronto this week. I am satisfied that I made this happen, and he is satisfied that it did.

Miho, his daughter is there too. How much she is like Sachiko [Hani’s first wife], and she is just now about the same age Sachiko was when I first met her. The same slightly shy way of looking at you, the same modesty. This is now all lost in the mother, but it lives on in the daughter.

21 february 1999. How much greater the display of public anger now that portable phones are everywhere. Never have I heard so many voices raised in ire. A boy with gelled hair shouting into his receiver, adopting that abusive yet whining tone of the wronged young. Seeing that he is observed he begins to gesture as well (though with only one hand)—the clenched fist, then fingers splayed in displeasure.

Very shortly, a fat yakuza with a permanent, pinkie in the air, rolling his consonants and calling the other party omae and temae. Seeing me watching he scowls and turns away. Later, a young man in a gabardine suit shouting into his phone and at the same time pissing on the seats of the parked bikes in the small shelter where he is standing. Noticing that he is observed, he just stares back and then starts to shout again.

I think this kind of behavior (except for the pissing) is only possible because of the portable phone. It is not anonymity that it offers, but distance. The other party cannot get back at the caller, cannot reach out and rebut.

11 march 1999. In my readings I find that in the Edo period, incense was thought of so highly that the term kyara—meaning highest-quality incense—became one of general approbation. Kyara clogs meant high-quality clogs, kyara women meant beautiful women. Also, find out that there was an Edo term indicating dangerous extravagance. Kuidaore meant an overweening taste for fine food, kidaore for expensive dress, hakidaore for lavish footwear. The implication was that this was a weak point, a source of ruination—particularly for those from Kyoto and Osaka who had come to fashionable Edo.

18 march 1999. [Numata] Makiyo took me out for a birthday dinner and brought along his daughter, Maki, now five. She is beautiful, a little girl version of him. They are very close, she and her father. He no longer speaks baby talk to her because she is no longer a baby, but he still dotes on her, and she on him. There is also a younger child, and I hear yet another one due next month—all girls. He says he wants a son, too. I ask if he is using the lottery method—try and try again.

We talk about what we have in common. Our travels together, his family, but we do not talk about the fact that I at one time loved him almost as much as he now loves his daughter. This always baffled him but, being a good person, he went along with it so far as he was able.

I look at Maki, much as her father must have been as a child, and wonder why I felt so strongly. Then, turning to look at him, late thirties now, my friend for fifteen years, I realize why—he is like a son to me.

25 march 1999. Tani calls. Also he wanted to tell me that he has become a grandfather. “That daughter of mine,” he said, “thirty-four, now. Always was lazy. Just slid under the wire, got the baby out. Nice little boy. They named him Kohei. Two months old now. I went to the big shrine here with them today. First time I ever went there. Nice place. Then we all had dinner.” About India: “Did you see any crocodiles?”

Consistency . . . Tani does not change, no matter what happens. This is, in the flux we live in, reassuring. Tani was interested in crocodiles at twenty-five, and he is equally interested at sixty-five.

27 march 1999. Re-reading Kawabata, The Sound of the Mountain. Can anyone now understand him? I wonder. All those flowers, all those trees, all that regard that is now so un-Japanese that it looks sentimental. Young people, with their Walkmen and manga, their portable phones—not only do they not know one flower from another, they do not even see them.

17 april 1999. My seventy-fifth birthday—diamond jubilee—lunch at the New Sanno Hotel, where University of Maryland was holding its graduation ceremonies, where I was speaker, and where I was awarded the degree of Doctor of Humanities. Wore a cap and gown, and was given a hood, with a white velvet lining.

Maryland has strong military connections here, and the hotel is a small bit of the Occupation, still working fifty years later. The prices are in dollars and there are other indications of transplanted America, all of which I found pleasing. There is a kind of symmetry. This is where I began, in Occupied Japan, and this, for one afternoon, is where I am ending—all that is left of Occupied Japan.

More, I liked the easy American good manners of the occasion. There was none of the solemn reserve, none of the inadvertent coldness with which many Japanese would invest such an gathering. People, the military (particularly the military) relaxed, out to put you at your ease. My dinner companion was a wing commander, and we talked about some existential touches he had noted in my speech and then went on to Camus.

2 june 1999. With Michael Rayns to the National Film Center to see the Gosho [Heinosuke] Where Chimneys Are Seen. Since it was shot largely on location, there unreels 1953 Tokyo. The plaza with its statue of Saigo where I now walk almost every Sunday, how small the trees were, and how empty the view. I see the old Nikkatsu Theater down below, long gone, long forgotten. One of the scenes is right in front of where I now live. It is filled with construction and the lake seems smaller. Also there seems to be no Benten Temple, now the principal ornament of my view. The structure was the postwar I knew, but more than eight years postwar . . . ? What moves me most are the people—that friendly, ragged, wily, beautiful, and hopeful crew that I can never forget, even now that they are extinct.

4 june 1999. Went to Maruzen for a photography exhibition—Meiji-period photos taken by early photographers including Shimoka Renjo. Scenes of the Fujiya Hotel, of Nikko, of all the other places early travelers liked. Also scenes of the various “professions”—naked palanquin bearers, a tattooed man, and a village girl, nude, standing, her hands crossed in front of her, all taken over a hundred years ago, everyone peering out from the sepia past. And all for sale. Meiji meishi prints, which even ten years ago might have cost a hundred yen in an antique store, are now half a million. Big prints are the equivalent of ten thousand dollars, twenty, and thirty. Such inflation is due to the snobbery that keeps things high here but, I suppose, such things are now rare. I saw no one buying. I wonder how much my modest fifty-year-old monochromes of Ueno are now worth.

9 june 1999. A bill is passed today that specifies the Hinomaru the national flag and “Kimigayo” the national anthem. This will be followed in a few years by a bill that will make them, once again, mandatory. Already, last month, a school principal was knifed because he refused both at graduation ceremonies.

14 june 1999. Early, a uniformed policeman comes to my door and salutes. He wonders if I would be so kind as to close my balcony doors from 10:30 to 10:45 a.m. and again from 12:30 to 12:45 p.m. The Emperor will be passing in the street below. I ask if I should draw the curtains as well—thinking of prewar customs when no one was allowed to look down on the Emperor. No, that would be fine.

I mention that his Imperial Highness has been driven back and forth under my window many times before without my having to close my balcony doors. He sighs, says he realizes this, and then tells me about the threat. He used the term kyohaku, which means blackmail. Since neither the Emperor nor the police force is blackmailable, I gather he refers to a bomb or something. I assure him that I will do as he bids, and receive again a smart salute. At 10:35 I peek from behind the curtains of my closed balcony doors, and there below progresses the modest imperial cavalcade—slowly and safely.

21 july 1999. [Oda] Mayumi came over for lunch, bringing me a new print—a green Kannon, very cool, reserved—quite unlike this ordinarily ebullient goddess. It reminds me of the Kudara Kannon, so quiet, so filled with dignity. We talk about goddesses in general and why they are so strong. She knows all about this, being a goddess herself. And strong. She and her lawyers stopped a plutonium shipment, turned it around in midstream, and sent it back.

Now she is here to show newer goddesses, one of which I have just been given. We talk about her fellow-goddess, Utako, who until age fifty sometimes had a twenty-year-old surfing consort. Not now though, too much trouble. She uses some kind of jade implement. Showed it to Mayumi.

This again reminds of us of another goddess, and after lunch we go to the Benten temple, in the middle of a pond now covered with opulent leaves and bright pink clitoris-like budding lotuses, and Mayumi gives a copy of her goddess book to the gently surprised young priest on duty.

“If we were a couple on a date,” says Mayumi, “Benten would break us up.” “Lucky we are not a couple on a date,” say I. But we are—I love Mayumi for her strength, her beauty, her acceptance of life, and her fight for what would hurt it. She is fifty-something now, and her fine, strong-boned face is lined with use, but inside she is still vibrating, the same woman I knew thirty years ago.

22 july 1999. I went with a new student, Karim [Yassar], to see a Kawashima Yuzo film at the film center. It—Ginza Nijuyon-cho—was just a program filler of the fifties, but it was filmed around the Ginza, and so I see again—living—the buildings, the streets, and the people of over forty years ago. There was the Olympia bread shop, where I used to find French bread, the only place in the city; there was the roof of the Matsuya Department Store that used to have plants for sale; there was the Sukiyabashi canal, with boats for hire.

Karim, fifty years younger than I, noticed differences in the people then and now, and wondered if they were always this friendly with each other, or whether this is just the movies. No, they really were. And I, too, noticed the difference. Now the young are closed, blank-faced, unsmiling, and hiding behind their portable phones or their Walkman or their held-up manga. They do not know how to look at each other, so they hide.

What catastrophe caused this? We wonder. Well, this generation was taught nothing. It had to infer everything, and did not do it well. Also, it demands nothing of itself—the latest gadget satisfies it; it goes to see Star Wars. What do they want, I wonder—other than a Sega game, a Prada bag? They can’t all be as empty as they appear.

Karim says they are not. He goes to school with some of them at Geidai, and he finds pockets of spontaneity, particularly among young people who come to the city from the country. He finds the nadir in “Young Town,” the land of the juvenile robots—Shibuya. There these youthful herds await a deliverer, someone to organize them, and a country to give up everything for. Someone like Mussolini or the Emperor Hirohito. Then we discuss the bill making both flag and anthem compulsory now being openly rammed through the Diet.

29 august 1999. More and more, girls are going out together. The streets are filled with their groups—sometimes in twos, more often in fours or fives. One notices because they are so noisy. They are always laughing. Hard laughter, as though it hurt, interrupted by squeals of simulated delight or surprise.

Boys do not act this way with each other. This is because boys are not trying to reassure each other. Also, perhaps, because boys do not have feelings for each other—usually. Girls, however, empathize. Each knows what the other has gone through. At the same time, each also knows that the other is a kind of rival for what those around her regard as desirable: a job, a husband, a child. So the empathy is wary and takes the form of continual reassurances and much noisy laughter to indicate what a good time we are having, just us girls together.

30 august 1999. The summer half gone. I walk in the evening in Sumida Park, maybe my first time there this year. It is still as beautiful as ever, though many more high-rises block the sky and there are no bats. The barricades for the fireworks tomorrow are up, and there are fewer people. I sit on a familiar bench, remember others with whom I sat there, and wonder where the summer went.

Ed and I were talking about the increasingly rapid flight of time. When one is older, he says, and he is three years older, time accelerates. Young, time is timeless, and a summer afternoon lasts a week. Old, it races, in a minute or two it is over. This is a blessing he says. Just imagine, he says, the other way around!

I sit and think about Nagai Kafu, who would this year be one hundred and twenty years old and whose big memorial exhibition I have just been to see at the Edo-Tokyo Museum in Ryogoku. There were not only the books and manuscripts, but also his glasses, his seal, his famous greasy hat, and his brown mohair suit with one of the buttons broken. The River Sumida, Peonies, A Strange Tale from East of the River, they were all written around here, though I do not remember this park being mentioned. (Others mention it, however—Saikaku for one.) But his spirit is here, the crumbling past, the passing time. He who regretted vanished Taisho would now regret vanishing Showa. Me too—and if I feel like that now, what will I feel like when I am dead?

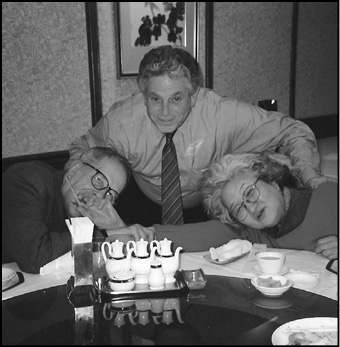

1 september 1999. Burt Watson came to lunch and we, two of the last survivors, talked about all the dead we shared: Herschel Webb, Gene Langston, Charles Terry, Meredith Weatherby, and Holloway Brown. Burt himself is holding up well. If I just glance, I see an old codger in a baseball cap. If I look closely, I see my old friend Burt there, owlish, and the finest translator into English of Chinese and Japanese poetry.

We talk of the strange way people have of regarding our companions. Ted de Bary drops in at Burt’s place in Kyoto. Burt says, “I believe you’ve already met my friend, Noboru.” Which he had. To which Ted says, “Well, I can’t be expected to remember if that’s the same young man you were living with before or not.” To which Burt now adds, “Imagine someone saying, ‘I think you know my wife already,’ and you say, ‘Well, I can’t be expected to remember if that’s the same woman you were living with before or not.’ ”

Then we went on to talk about the strange prevalence of people of like preferences among foreign Japanese specialists. I mention that someone is writing a book about this. “Oh, must read it,” says Burt.

3 september 1999. Watching some young people at the Fantasia [game center], I observe their satisfaction with all the virtual reality. There are games where you zap dinosaurs and the walking dead, others where you pilot fast planes, drive fast cars, others where you don helmet and glove and have adventures that I, standing on the outside of this reality, cannot see. And I wonder at such popularity.

Then suddenly, without trying at all, I understand. Virtual reality is never threatening. This is because it is always virtual and never real. And the reason for the preference is that reality is read as dangerous.

This is, come to think of it, what one would expect in a land where every mother tells every child that something or other is menacing (Abunai da yo!), where teenagers are continually advising each other about dangers, real, imagined, or hoped for (Yabai da yo!), and where a populace is careful, measured, and suspicious. One never knows where looking at strangers, much less talking with them, might lead.

Much better the manga comic book so you will not have to look at reality, even better the Walkman earphones so you will not have to listen to it, and best of all, the various virtual reality machines where you no longer have to be, strictly speaking, really alive any more.

It is possible to live a life of nothing but special effects. These are always virtual, in that they have no other reality. Fashion offers a beginning—hence its extremes: at present carefully grayed hair on the very young, chestnut faces stained deep with something that comes from a tube, lipstick (for the girls) that is corpse-like, and (for both boys and girls) carefully plucked eyebrows and sparkles that stick to the skin and glitter.

But fashion is still somehow too natural. It is attached to something that is real. Therefore, it is safer, to deny the real entirely and enter into a state (drinks, drugs, virtual reality) where nothing is real anymore, and therefore nothing is threatening.

But what a world have we made for ourselves (for Japan is not the only place preferring the virtual) where we spurn the real? Japan traditionally has preferred something other than rank reality, to be sure, hence the classical Japanese garden, ikebana, bonsai, etc. But virtual reality was invented for those who are afraid. Therefore the world had to be fearful before it is invented and (in Japan more than elsewhere) perfected.

The couple I have been looking at laughs as they manipulate their buttons and it is impossible to say that this laughter hides fear. But then you do not have to know to be afraid.

4 september 1999. Recently fewer homeless in the park below me. Could times be getting better; could the authorities be finally doing something? I wondered. There were now just a few, one or two of the more seasoned, including the homeless prostitute and two younger crew-cut types, always drunk, always abusive.

I saw them several nights ago, squatted in their hoodlum manner in front of a peaceable old man who had been a part of the scenery all summer. One was saying to come on, cough-up, and the other was saying that he knew he had two hundred yen hidden on him. I thought they were marauding high school boys, notorious for picking on the weak, and that they would tire and leave.

Today, however, at a train station down the line I saw the same peaceable old man, sitting in the midst of the commuters. I asked him what he was doing. He said that they had been run out of the park, all of them. It was now too dangerous. There were a lot of homeless yakuza (his term), and they took it over.

I then understood why there were so many fewer homeless, and I wondered that the jungle should be so near the surface of our ordinary lives, and that we should be so blind to it. I gave the peaceable old man some money, but felt none the better for it.

5 september 1999. Talked with Philippe Pons on the phone, and he asked if I was still entertaining my goût de la boue. I had not thought of that term for a long time, but as I this time heard it I realized that indeed I was. Why else am I roaming the park? It is because of this “taste for mud” (the term does not translate too well)—but, I wonder, why then do I have this taste?

It is because I, like many another, confuse the “low” with the “real.” Somewhere Bernard Shaw spoke of the sentimentality of linking the poor with the virtuous and making the monstrous assertion that to be penniless was to be good. I do something of the same. To me, the poor are more real, more “themselves” than the well to do. It is true that they live in a fashion more elemental—but more “real”? Or, is it because I am intimidated by the moneyed? They also have power. I prefer the powerless, because I am not intimidated by them. There is nothing intentionally sinister in this, but I must think more deeply about the origins of such inclinations as the goût de la boue.

4 october 1999. To the Korean restaurant with Ed. We talk of various kinds of food, and he asks me if I knew that when cannibals eat humans they must be careful to also consume lots of vegetables, because otherwise human meat is difficult to digest. He says that there may be innate enzymes that prevent digestion. I say that this is unlikely; that the prohibitions against cannibalism are cultural. He is not certain, and then suggests that perhaps the genes could be trained, through careful cannibalism, to remedy indigestion.

This leads to talk of other kinds of odd habits. I tell him that the Goncourt journals speak of Napoleon’s habit of rolling small pellets of his excrement while talking. Ed wants to know where it came from. Did he bring a bowl of it to table?

This somehow led to a discussion of the stilt shoes now worn by young women. What could it mean? He wonders. I say it means they want their legs to look longer. He wonders at the possible high incidence of broken ankles. Then he says that the country is truly changing. For years he thought that there was change on the surface, but the core was holding. Now he does not think so: the family system in ruins, the Confucian ethic dead, employment a shambles, and no one making children anymore. I say that these are late Hellenistic times. He says that shortly the last Japanese will go on display, like the last Tasmanian.

12 october 1999. Dae-Yung and I went to Nagatoro, a place I had not been for over forty years—back in 1958 when Tani got married for the first time. I somehow remembered the cliffs higher, the boat ride bumpier. But this time it was fall and back then it was spring, and the water then was all mud and now it is green as jade.

Nor did the boat stop at the lair of giant carp, and no one jumped naked off the craft. We were sitting with families and their squirming children, and the water was so low there was no great pool for the giant carp anyway. I found myself remembering an even earlier time there, maybe 1951 or so. This time it was Meredith and [Yato] Tamotsu and Tani. He was wearing a suit for some reason, and Tamotsu was being very funny telling stories, and no one knew he would be dead ten years later.

I tell Dae-Yung about these memories, about this being my third time at Nagato. He never met Meredith nor, of course, Tamotsu, but he has met Tani. How old was he? He wants to know, knowing him only an elderly man. About thirty, I guess. So young, he says, now thirty himself, shaking his head at time, at life, as we drift down the deep green river.

Later, as so often, his thoughts turn to death—mine. He has prepared himself with various contingents. Until recently he was going to carry me up to some mountaintop and we would both live in a temple and bang drums until my demise. Now, however, he has given it up. Either he will come here or I will go there. In either event, he will take care of me.

I hope to die in hospital. It is the best among bad choices. They insure a more or less painless departure and clean up the mess afterward. The ashes will be taken by Dae-Yung and Fumio and dumped into the Inland Sea. They have agreed, and the lawyer has been notified, and dumping ashes is no longer considered by Japanese law to constitute the abandoning of a corpse.

We talk over all this while enjoying the flowing river from a restaurant window, looking in the late afternoon sun at all the fruits of the earth as we slowly spoon our persimmon sherbet.

8 november 1999. I go to the premiere of Oshima’s new film, Gohatto. It is sober, serious, and beautiful. The style is recognizably his, but it is now autumnal, contemplative. He comes onto the stage, walking haltingly, his hand on his thigh as though pushing himself forward. After his stroke he created this film through willpower alone, and now appears before its screening, standing there, upright, victorious.

In the audience is his wife [Koyama Akiko]—we bow. I would not have recognized her, so altered has she been by this illness and its cost. It is as though she herself somehow absorbed all that pain and despair.

9 november 1999. I go to the National Film Center to see Umi no Seimei-sen, the first feature-length propaganda film, a documentary edited by Aochi Chuzo in 1933. It is about the Marianas and the Carolinas, and opens like a travelogue, with all the strange animals and fruits, with bare-breasted beauties and Yap warriors in loincloths. Then, bit-by-bit, its annexation by Japan is touched upon. The natives happily assemble to greet them—they are naked, but the Japanese are in full uniform. Eventually we have the natives in clothes and singing the Japanese national anthem and doing banzai for the Emperor. Then, with maps and martial music, we are shown why these islands are important and what would happen if they were threatened. It is like propaganda from any country, except for those animals and fruits and the long lyrical sequences of palm trees. Back then, Japan found nature just everywhere.

I then go to Ueno Station and eat in the station buffet—have a typical Japanese buffet meal: salted fish, seaweed, miso soup, and tofu—the sort of thing one used to eat all the time and rarely does now. And as I am eating the fish, I look around and remember these Ueno Station corridors fifty years ago when the natives lived in them among strange animals, like rats, and ate strange vegetables, like American rice. And they would have sung the American national anthem if America had insisted, and would have cried three cheers for MacArthur if required.

13 november 1999. Last night in front of the park three rental busses stopped and a number of people, all carrying shopping bags, rushed out and, encouraged by numbers of cropped youths in Puma sweat suits, began running through the park. This morning I heard loud chants and cheers that went on for a long time, and when I went out I saw the Puma boys, each a group of three, earnestly instructing them. One girl had to get down on the pavement and pretend to scrub it, in the meantime saying she was sorry and would never do it again. Another was instructed to approach all strangers.

Interested, I asked a cropped youth what they were doing. “We are a part of the Try to Be More Happy Group.” I said I had seen them last night and wondered where they slept. “Oh, no one slept; we stayed up all night to prepare for being happy today.” I asked how one managed to be happy. He explained: First, one signed one’s name and address on these forms and then gave five hundred yen to join. Join what? I asked. “Oh, Nakamura Genpei’s Happiness Group. You have probably heard of it.” I admitted ignorance. The girl was pushing against me, pencil in hand.

“What is that woman doing scrubbing the pavement? Is that being happy?” “No,” said the boy, “but our Teacher thinks we have to show some examples of unhappiness before people will join us in our mission to be happy.” I thanked him and walked away.

And this is going on at the very time when the Aum trial is announcing some of its results. Today the driver of the subway poisoners is given life. One poisoner has been sent to death row. And tonight coming home I see Puma-suited youths in the park stopping just everyone. Getting nowhere, but stopping just everyone. Much later I hear them in park, exhausted but chanting away, their calls now hysterical. Terrifying.

24 november 1999. I take Edwin and Rachel McClellan to lunch at Spago. We talk about the suicide of his friend Eto Jun. “Sat in the bath, he did,” said Edwin. “Slit both wrists. Very Roman.” “Like Seneca,” I said. “But by no means instantaneous,” said Rachel. McClellan is giving the memorial talk on Eto at International House. I had earlier asked Seidensticker if he wanted to come with me. “Not on your life,” he said. “A perfectly dreadful man.”

“His wife had died, you know,” said Rachel. “A perfectly lovely woman, and he was lost without her.” I looked at them. She is lame and her husband pushes her wheelchair everywhere, and they both handle this permanent impediment with patience and bravery. If he were to die where would Rachel be?—or the other way around.

25 november 1999. Finishing the Alan Sheridan biography of André Gide, I am filled with admiration. For the book itself, to be sure, but also for Gide himself. In his eighties and still out on the street, as promiscuous as ever. What an inspiration, what a model to emulate.

27 november 1999. As the economy collapses prices remain high. This is, I guess, very Japanese. In some other countries there would be at least a few merchants who would lower their expectations. Not here, however. There are new alternatives (the hundred-yen malls), but nothing established lowers anything. Perhaps it is because quality is judged by price. If you lower the price you lessen the quality. There is thus really no such thing as a bargain. Indeed, some raise their prices as though to tempt through exceptional quality—this is the way Wako Department Store works. The goods are in no way exceptional, but the prices are. Consequently anything merely wrapped in Wako paper is first-rate. I remember tales that in the far hinterlands people used to paper their walls with Tokyo department store paper, simply to give tone.

1 december 1999. Karel [van Wolferen] back in Tokyo and over for lunch. He is enthused about some new ideas he has been having: One of the reasons that the description of the Japanese economic system has been so inaccurate is that all the wrong questions are being asked. When foreigners (particularly Americans) ask a question, their premises determine what it is—that and their agenda. This is not the way to approach it, he says, as indeed it is not. I mention that in the literary field, reforms have been going on for some time, to say nothing of anthropology, where it is has been determined that the very presence of the anthropologist determines what kind of information he receives. Karel is quite right, however. Such an idea is radical in economic circles. If you so rigidly depend on your own system of public and private sectors, you will not notice that Japan has none.

2 december 1999. To International House to hear Edwin McClellan talk about Eto Jun. Spoke of him as a teacher and as a friend. The political persona was not there, since Ed, as he told us, never saw it. And so he heard others denounce Jun (who once left a dinner party because some American was there), but never understood why. He still doesn’t—but gave us some indications. Those who hated him did so because he was one of “them” and not one of “us.” The divide was political—after Princeton had provided for him, he then went and said that Marius Jansen waddled like a duck. Ed deplores this, but only on grounds of manners. He remembers his friend with warmth and sorrow.

5 december 1999. “We are born, so to speak, provisionally, it doesn’t matter where; it is only gradually that we compose, within ourselves, our true place of origin, so that we may be born there retrospectively.” This is Rilke, as quoted by Coetzee. The poet, hating Austria (where he was born) and spurning Czech (his citizenship), decided to be French. I may have rejected the U.S.A. where I was born, but I did not decide to be Japanese. That is an impossible decision, since the Japanese prevent it. Rather, I decided to decorate Limbo and become a citizen of this most attractive, intensely democratic republic.

15 december 1999. End of year, end of millennium. This one especially dramatic because of the computer chip crisis—the Y2K affliction: the fear that our machines cannot read past ninety-nine. This well fits the apocalyptic end of this most brutal of centuries, the one where it was discovered that violence was prime entertainment. People are afraid of the Y2K the way that children are afraid of deserved punishment. Made all the more delectable because we do not know what will happen. Imagine—trusting our lives to machines we do not even understand.

16 december 1999. Still, for the other millennia people trusted gods and they didn’t understand them, either. The difference is that the machines are ours. We made them. But, come to think of it, that is not a difference. We made our gods too. Since I early learned to get along without gods, have lived with a minimum of machines, spurned portable phones, e-mail, and Internet because I do not think much of promiscuous communication, I feel not superior but curiously out of it. As though there had been a party to which I was invited but did not attend.

17 december 1999. Glenn Miller—the last popular music I remember listening to. Of everything after that I know nothing. Rock is noise to me. I missed most of American pop culture by not being there. I asked just recently who the Who was. This is not, I know, a loss—particularly in that I had other music. But I find it curious that, like Briar Rose, I managed to sleep through my generation.

I did so by coming to this magical land where everything looks much the same but acts sometimes otherwise, and where I was forced to share nothing—much less pop music. But, since I escaped all this, I can also know what Rip Van Winkle and Urashima Taro both felt. But they interpreted loss. I feel gain.

30 december 1999. Japan shuts down earlier than usual this year. There is such poverty (recession they still call it) that every day’s wage saved is a gain for the employers. Even the banks and post offices are closed. Yet there is little of the accustomed New Year emptiness. Most people have no money to travel, and besides they are afraid to—on the first day of the new millennium planes will fall from the sky. Against further threats people today crowd into stores—which will close tomorrow—to buy food, water, flashlights, and oil heaters. Electricity, that force that shaped our century, is no longer to be trusted. In a few days they will feel strange, facing their useless hoardings, but right now they fearfully buy. Me too. I go to the bank and take out enough money that I can live a week or two in case the cash machines fail.

Amid all of this, a rare public rudeness—people shoving each other out of lines, spiteful remarks at others fumbling at the cash machines. Just today the wife of a former prime minister was mugged—a man on a motorbike grabbed her purse and knocked her down to get it. This would not make the news in some other countries, something this common. Nor did it make the news here, but the reason was different. No one in the media wants to admit what is happening.

31 december 1999. I go with Chris [Blasdel] and Mika [Kimula] to see in the New Year at the Benten Shrine in Inogashira Park, outside Tokyo. It is cold but clear, and the stars stare down as we walk through the chill to the distant shrine, the fire of which we can see through the bare groves. It is near midnight.

Then we hear cries and shouts and turn to look. There, on a bridge spanning the large pond, are a group of high school children. The girls are screaming with excitement and the boys have taken off their clothes and are standing on the railing of the bridge, one of them with his portable phone to his ear.

He is counting down, timing himself with the telephone company’s exact-time service. His hand is in the air, fingers extended. All five, then four, then three, then two, then one. Then all the boys, five or so, jump off the bridge and into the pond.

The girls shout, the boys cry, out thrashing in the pond, the dark water now white with waves. Then, like otters, the boys clamber up the banks and dance around in the cold; one of them lost his underwear, holds his hands over himself and laughs.

Seeing us there the wet boys race forward and throw their arms around us shouting New Year’s greetings. I put my arms around a student wet as a seal and we kiss each other’s ears, then he races off as the girls squeal and again he jumps into the pond followed by all the others.

A temple bell is booming, the girls are dancing, the boys are clambering up the banks to join them, my ear is wet, and the fires of Benten burn, warm in the distance. For this one moment everything returns—it is the new millennium, but my fifty years have not passed. They have been for this time returned to me. “Happy New Year,” sing the jumping girls and the leaping boys.

Originally Richie intended to permanently close the Journals with the above entry. And indeed, he wrote no more for several years. But, as he said at the time, he came to miss the daily record and, more important, living seemed to have less meaning when it went unchronicled. Other writings for the year included his final book on cinema, A Hundred Years of Japanese Film. Also, in the following year (2001), Arturo Silva’s The Donald Richie Reader appeared.

20 january 2002. Ate lunch at the cafeteria at Ueno Station. Walked in, sat down, waiter appeared. “What’s for lunch?” I asked. “Mother and child over rice,” he said. “Sounds good,” I said. Ordered and ate oyako donburi, mother chicken covered with child egg. No one thinks this strange, and it is not strange in Japanese, only in English.

15 march 2002. Lunch with Chizuko [Korn], the first time I have seen her since Frank’s death last fall. Cancer of the brain, and I sat with him, my oldest friend, as he napped. And now, half a year later, she has been through the awful final days: the cremation, the scattering of the ashes, and the trouble with the daughters. She picks at her salad and says she has no idea what to do with herself—she is no longer Japanese (he made her an American citizen for tax purposes), and she no longer belongs here anyway. Still she is tough and brave and, somehow, smiling.

1 april 2002. Last week, a day or two after his eightieth birthday bash, Ed [Seidensticker], finishing his morning shower, was drying his toes. The bending threw his artificial hip out of its joint and there he was, on the floor in enormous pain, and all alone. It took him an agonizing hour to get to the phone and then, when help came, it could not get in because he still had the safety chain on the door. The janitor had no cutting tools, nor did the ambulance. Finally, the firemen were called, and one leaped from an adjoining balcony to his; the door was not locked, and he got into the apartment, and when he told me about the fireman coming right in the window he again wept with relief. Now he is much his old self, though much muted about the inconvenience he must endure. He is in a wheelchair and will be in hospital for at least another three weeks. Then he will have to wear some kind of wrap-around spandex affair to keep his hip in place.

14 april 2002. Ian [Buruma] interviewed me on the Occupation for his BBC radio documentary, and we then met Philippe [Pons] and went to a Korean restaurant. He, author of a book on the bas-fonds of Japan, has found a new dohan kissa, right around the corner from me. He has been twice, and says the clientele is younger than at the Shiro but it is also more expensive—and, of course, you still have to have a girl to get in. In Shinjuku, on the other hand, is one where you can go in by yourself and look away to your heart’s content. Shows me where the Ueno one is. I walk by it every day and never knew. We discuss the goût de la boue that we both share. “I share it too, you know,” said Ian, slightly put out by our exclusivity. No, you don’t, not at all, we reply. You are married with a child. “That makes no difference,” said Ian, defending himself, “I can still appreciate the goût de la boue.” It had become a point of honor, I saw, so allowed that perhaps, just maybe, he could. We then went into a definition of terms.

15 april 2002. Thinking about writing and how difficult it is to capture anything like the reality of what you are writing about, I remember what Kurosawa once said when I asked him the meaning of some scene or other: “If I could have put it into words I wouldn’t have had to film it.”

There is something then in the nature of words, of language, that prevents this apprehension. Perhaps it is because words must put things into code before they can communicate. The writer writes his encoding, which the reader, if he can understand it, decodes as he reads.

“She drew her dagger and stabbed him.” Not at all realistic. Our minds trip over the words. They are too familiar and leave out all of the details that individualize reality. Already, what we wrote is a genre scene, resembling all others, lifeless.

“The glint of her silver blade, the dripping of his scarlet blood . . .” Also bad, but at least this kind of writing attempts to convey an impression, something like what we might have felt had we been there. A stab at uniqueness, but no bull’s-eye.

In fact, try as we may, words hit no bull’s-eyes. They are not made for that. They are made for general description, for describing genre scenes. But if you made this sentence into a film, then you would have a unique moment, done once for all time and packed with real detail, no matter how phony the event.

This too is encoding, but how different. This is because the encoding process is special. Read the above sentence, then see this scene (in Rashomon, except for the blood), and note the differences. One is more real than the other; one communicates (on one level) more than the other.

25 april 2002. Though it is a bright spring day I suddenly, definitely, feel autumn. Why would that be? I wondered. Then I smelled it. Smoky, pleasantly unpleasant, reeking of the fall. I looked around. An unseasonal chestnut seller, his smoking cart (the nuts baking in hot gravel) sending this strange smell, which is to me completely autumn.

At first whiff I saw not the pleasantly, placid streets of springtime Ueno, but the dappled horse chestnuts of the Rue Canebière in wartime Marseilles, and the dusky streets of Brindisi after dark, the flares making holes in the night, and the dock at Bari, when the sellers came out after the sun went down and it was cold enough that the chestnuts warmed the hands. This was when I first knew this smell (none in Ohio), and it is to these images that the odor returns me.

Strange, the reality of this illusion. Proust says taste, but he could have said smell. They are the same. I stand there and see the past still faintly stenciled on the present, but fading as familiarity follows.

30 april 2002. Out with Susan [Sontag]—had not seen her since last fall when she came to my Japan Society dinner right after she had been attacked on TV for writing her courageous assessment of the World Trade Center attack. In the short New Yorker piece she reminded the U.S.A. that there were reasons for its being so hated—that is all. “Oh, it got worse,” she says in that fine way she has, as though speaking of someone else. “Death threats, midnight calls.” I say that if that happened to me I would have folded up. “No you wouldn’t, you just think you would. Anyway, you just wait till they stop.” I ask what kind of people. “Oh, professional people, intellectuals, no low life.” She tells me that The New Republic had an article that began by rhetorically asking: What do Saddam Hussein, Osama Bin Laden, and Susan Sontag have in common? Then answering it with: They all wish the destruction of America.

It is holiday season, Golden Week, and she remarks that there are no Japanese flags. We compare this with the U.S.A., where the American flag is now the most commonly found decoration—Stars and Stripes just everywhere, a country swathed in bunting. We discuss the implications of this triumphalism. “Well,” she says, “this is the first time in history that one country has had this much power.”

3 may 2002. Susan and I go to Asakusa, where we went during her first trip, more than a decade ago. “How clean it all is,” she says. “I remember it being much more scruffy.” Asakusa has been gentrified, turned into taxidermy, I say. We tour the neat little clutch of Edo temples, and she notices that they all now look plastic, even the real ones.

What will happen to Japan, she wonders, and guesses that the first thing to really go will be the banks. I tell her that everyone is now living on his or her fat, and since Japan was financially obese there is a lot of that. She tells me a “joke” that her son, David, told her: What is the difference between Japan and Argentina? Answer: Three years.

She finds much else different and at the same time now sees things she formerly did not. “These people do not know how to have discourse.” Invited here for one of these expensive “conferences” among intellectuals, she tells me what it is like, and gives a very funny impersonation of a famous Japanese architect making a presentation. “And I saw this building. And it was very big. And I thought, this is big, very big.”

I mention that the language does not really accommodate discourse, but it does encourage analogical talk, one thing leading to another, and I mention that in Japan it is suji instead of plot. At once Susan is interested. With her it is a way of learning.

Out comes the notebook and suji is spelled out. I tell her about that favored form, which looks no better written than it seems spoken: “following the brush” (zuihitsu), spontaneous nattering. I suggest that this is what the other people in the conference were up to. She writes all this down, and at once agrees that there are, certainly, different modes of thought, then she stops.

“Still, everyone is so corrupt—intellectually, morally.” We cast about for reasons why this should be so, and she, only here a couple of times, hits upon the one real answer: “It is because everyone is afraid. They do not want to be punished. And this country is so crony-prone, so given to authority, that if you do speak out, if you are intellectually honest, you will certainly be punished. If the people on my panel spoke out they would not get invited to the next panel, architects would not get commissions. That is what I mean by corrupt.”

Corrupt Susan is certainly not. Have I ever known anyone more honest, more forthright, more brave? I think not—nor anyone more moral. She can cut through cant; can see through any amount of bad faith. Just to be with her is to think more clearly, to become more courageous.

4 may 2002. I look from my balcony and see that two plainclothes cops are making a derelict woman move her belongings—a set of wheels piled with cardboard boxes, many shopping bags filled with newspapers—the kind of things these people cart about with them.

I used to wonder why, but I really knew. Why do I have books in my bookshelves and clothes in my drawers? It is because I am defined by what I have. My belongings are proof of me. If I had nothing, then I would be nothing. Me in a foreign city, me in the train, me in the airport—I always have my bags about me just as she does. And I imagine the panic I would feel if these worthless things were taken from me.

From high above I watch as she tries to wheel away her cart but no, they want her to go far away, not just a bit. They gesticulate. Far, far, far. So, as though reluctantly, she pushes her cart and tries to gather her bags. But, like all of us, she has too much.

Her further adventures I decline to watch, though I wonder why they are doing this to her. When I descend the street to go out she is gone, but they are there, radios in their ears. They are waiting for a royal—probably the Crown Prince or the Emperor is coming from Ueno, and these two have been given the task of clearing the roads.

5 may 2002. To the hospital to see Ed—a precise reprise of last year: in the shower, washing the feet, hip gets dislocated, finally reaches the phone, help comes, to the hospital, knocked out, hip manually reinserted. All this happened three weeks ago. He is sitting in a wheelchair, looks up, and smiles. “It seems the only solution will be for me never again to wash my feet.”

I bring him the paper in which I review his memoir. This pleases him. And we speak of banks and the coming collapse, and he is of the opinion that it is richly deserved. Mentions that further injury was that he had planned to finally take out state insurance the very week the accident occurred. So he has to pay the enormous medical bills that Japan insists upon.

19 may 2002. The Sanja Matsuri in Asakusa, the greatest of festivals—thousands in the streets, over a hundred floats on the shoulders of naked young men (and some clothed young women too these days), all noise and sweat and violence. And it went unseen by me, once again.

I used to be excited by it, used to go every spring, often with [Yato] Tamotsu, and I would ogle and he would snap away. He died (on this very day, the day we were to meet by the big Asakusa gate), but that is not why I no longer go to see the spectacle.

I don’t go because I am not satisfied merely to watch. I am excited by it, and I want to touch it. Several times I succeeded, but now I find that the kind of exclusion I thought I was used to is still painful. It is so dramatic, this exclusion. But at least it is natural and understandable. What is less so is my ambition to be a part when I know that I cannot.

15 october 2002. Rereading, after all these years, André Gide’s Si le grain ne meurt, I find a compelling sentence. Of some incident he writes: “And if it is indecent to relate it, it would be still more dishonest to pass over it.” Though I have nothing to relate that I consider indecent, it is Gide’s constant attempts at honesty that continue to impress me. So this sentence is enough to push me to again begin some accounting for my days.

16 october 2002. Most of my life has been spent regarding Japan—observing it, considering it, comparing it. And I have been happily occupied; have learned much I would not otherwise have known. It could have been anyplace—even places I like better: Greece, Morocco. The results would have been much the same, since I did not remain where I was born.

But now I can see that I am getting older because there are waves of memory, a tide that wants to sweep me back to where I came from. This will not occur, but I must experience its effects.

I, who have spent my time meditating on difference, am now presented with “similarity”—what I experienced then and what I remember now. Forty-five years ago Igor Stravinsky told me that at his age (which is what mine is now), he could for the first time remember the smell of the St. Petersburg snow of his childhood. Now, just today, out of nowhere, comes to me the sweet, watery taste of mulberries.

There was a tree in my aunt’s garden, and I used to climb it to pick the white and purple fruit, to get it before the birds got it since, even back then, people did not much eat mulberries.

I remember the reason offered. The birds are fond of them, you see, I was told, and the seeds go right through them and so every tree is born from excrement and you don’t want to eat that, do you?

I did not then know that many plants and trees thus grow, but I do remember seeing that this made a kind of dim bond between me and the mulberry tree, and that I ate more berries than ever. And now, suddenly, this remembered taste.

17 october 2002. My balcony overlooks the great lotus lake. I am often on the shore, sitting there, enjoying my goût, nay my nostalgie de la boue. Why is mud so comforting? We have mud baths, along with sand baths and seaweed baths, where you are covered with the stuff. Medicinal claims are made, but I think it is the comfort of being thus lathered that attracts.

The only other time this will occur is after we are dead. Whether cremated or not, the remains are covered with earth. “When I am laid in earth . . . ,” sings Dido, and Purcell sets these words to a descending melody of grave beauty, both accepting and celebrating.

The nostalgie extends to other kinds of boue as well. The other day, in the park, I smelled something I could not place. It was pungent and meaty, but at the same time it was rich, even opulent. And familiar, so familiar.

Tovey writes of a similar experience with a melody he knew well but could not place. It was ambiguous, beautiful, and difficult. And when he did recollect, it turned out to be one of Brahms’ most famous tunes, but for a time rendered innocent again, luxuriating in its originality, freed of all those hearings that had made it famous.

So this smell, which I eventually identified as shit. Someone had shat in the bushes. The odor at once lost all of its interesting qualities. These were instantly replaced with thoughts of dirt, filth, etc. It was no longer a fragrance but a stench.

I stopped and considered. It was the same smell. It had not changed. What had changed was merely what I chose to think about it. Or had been made to think about it. My initial reaction had been the authentic one.

Walking slowly homeward through the park, the sun setting, the pond slowly disappearing into the dusk, I thought about my liking for mud, fecund mud. My equally strong attraction as well toward a different kind of mud—the smell of humans, their armpits, their crotches—even their smegma, which as a child I thought was a Greek island.

In the growing dark it seemed natural that I next consider the dead, these now useless bodies slowly disintegrating, and the sweet smell of death. All of this seemed a part now of the mud that nurtured the lotus, which I could come and see tomorrow morning blooming pink and glorious for just one day.

18 october 2002. In Japan, the incessant urge to aestheticize—everything, from tea ceremony to capital punishment. What this means is bringing everything to an extreme order, which is then presented balanced, and regularized.

In the park I look at the homes of the homeless. Cardboard boxes precisely placed, a blue tarpaulin exactly draped. Inside, the found blanket folded as neatly as it would be at the Imperial Hotel. At one side a smaller box—this is for the shoes. The effect is not only utilitarian; it is also “beautiful,” that is, in accordance with the principles of good taste. And this from some anonymous builder who is completely severed from the common opinion he still represents.

23 october 2002. What phrase is most overheard in today’s Tokyo? It used to be sumimasen (excuse me). Now it’s ima doko? (where you at now?). But, apart from such portable phone use, the one I am hearing more and more these days is hazukashii. It is used in a very open fashion by men and women alike, and it describes self in an apparently attractive stance: being ashamed or embarrassed. I wonder why.

I cannot imagine an English-speaking nation where every other phrase is: “Oh, I was so embarrassed.” Yet I have heard Japanese footballers thus sugar their remarks. Is this, too, a legacy from the police-state days of 1604–1858, where you were required to show yourself in disarray, to apologize for simply being, the shogun’s power so internalized that being craven was good manners?

26 october 2002. Coming back through the rain I am stopped by a young woman who asks me if I am Japanese. I ask if I look Japanese. She says not at all, but that sometimes foreigners just don’t know where to go of an evening—she has a nice place and perhaps I would like to come. I decline, and she thanks me and proceeds. Hopeless to attempt to connect my perhaps appearing Japanese with her further request. I am like borrowed scenery, and her query was merely to find out if I could speak the language or not. If I could, I was potential. And the rain continues to fall.

28 october 2002. Big moon out tonight, but small signs that all is not economically well. We have the newspapers to assure us of coming prosperity, but we have long ago learned to distrust the papers almost as much as we doubt the tube. The smaller the sign, the louder it speaks.

Usually I am ignored when I walk along the Nakamichi, that frantic little street in back of my apartment where every evening touts gather to cajole customers. The boys carry menu cards with pictures of girls on them. The girls themselves display their charms (bunny outfits and the like), and attempt to lure the sarariiman into their basement lairs.

Now, however, business is so bad that the passing foreigner is also accosted. You come my house? asks a hesitant lad in English. Why? I ask. Drink, he says. I shake my head. Fuck? He says, but so tentatively that it sounds like a conjuration, a spell, or a hex.

Earlier, Ginza, too. Business so bad that outside the pretentious Sony Building there stands a small girl dressed as an “English” maid with lace cap and frilly apron, and she is passing out flyers for the Briar Rose Pub. And over it all—the moon, now looking like an advertisement for something.

29 october 2002. There are cats in Ueno Park, quite a number of them now. They take the bread from the pigeons and steal bits of dried squid and rice crackers from the sleeping homeless. In so doing they have become quite tame—once turned feral, they are now again domesticated. One of them is rubbing itself again the thin shins of the smallest of the resident transvestite prostitutes.

“Looks like you have a friend,” I say.

“Only one so far,” he replies, ruefully. “Really bad tonight. No customers.”

“And you with a family,” I say, sympathetically. I have seen him with two of his children and once with his wife. It is her clothes he wears.

“Well, there’s always death,” he observes.

“But you wouldn’t make your family . . .”

“Oh, no, just me.”

The cat purrs, rubbing itself on the man’s wife’s stockings. Then he adds, “We are all in Buddha’s hands.”

“Buddha’s lap,” I correct.

He smiles, “I wonder if Buddha’s got a big one.”

And the cat rubs and purrs.

30 october 2002. Smells—they change too with the years, just like sights and sounds. On these very streets the odors were those of roast squid and broiled eel, of pickled radish, and above it the brazen scent of beer, and above that, like a piccolo, the schnapps-like whiff of shochu.

Now, though these foods and drinks are still available, the smells are the sweetish reek of the hamburger, the oily stench of the French-fry, and the costly scents of the young.

1 november 2002. All these homeless, all these liveried people trying to get you into their establishments, all the talk in papers and magazines about the new poverty—and yet . . . The new Hermes store is packed; so is the new Vuitton “Centre.” So are the fanciest restaurants. People may be living off their fat, but how much fat can you carry around?

I also hear that this recession is really an engineered event, intended to fool the world, particularly the U.S.A., and excuse the criminal banks and the idiot government. I do not believe this, but it would help explain.

4 november 2002. Showing at the Press Club of that film about me, Sneaking In. I’d seen it several times before and was hence mostly over the shock of viewing myself as I actually appear rather than as I remember myself, or as I currently like to remember.

And again I am struck by how much I am like my relatives. The way I purse my lips, the narrow look—that is my mother. The measured gravity, the specious reasoning—that is my paternal uncle.

Have not before seen the film with my peers, however. They behave well enough. During the questions afterward nothing much except for one Japanese man, who is confused by the parade of personae, and asks, “Who is this? Critic, filmmaker, s/m addict?” (This last inspired by a clip from my Cybele, a film made with the Zero Jikken, a group that would do anything.) “Who are you?”

This was a pertinent question—indeed, what the film had been about. I asked the audience what it thought. No answers.

10 november 2002. Leo Rubinfein over to ask questions for his book. He asked me what I most regretted, having lived half a century here, and witnessed all the change. I said that I most regretted the loss of a kind of symbiosis between people and where they lived, a kind of agreement to respect each other. I again mention the paradigm—the builders make a hole in their wall to accommodate the limb of a tree. No more now. It is more expensive to make a hole than it is to cut down the tree, just as it is cheaper to raze than to restore. And since the environment is now so different, the people are different. This is symbiotic, too, degraded environment makes degraded people who make more degraded environment.

And with it I regret the loss of a kind of curiosity. People used to be curious about each other. Now they have their hands full with their convenient and portable environment—Walkman in the ears, manga for the eyes, and the portable phone (which now contains their lives) in the palm of their hands. Many Japanese no longer look at each other, or those they talk to—those on that select menu of known voices on their phones they cannot see. These robots, I regret.

11 november 2002. Rainy Tokyo—and from my elevated seat on the Yamanote Line I look out at the thousands of revolving rooftops, glimpse the hundreds of streets stretching away from every vista, stare at the improbable complexity of this tangle of a city, and suddenly understand the affection of the Japanese for M. C. Escher. He with his thwarted perspectives, his people going up and down, over and under at the same time, his lunarscapes shown from left, right, above and under, simultaneously. This impossible sight from the Piranesi of our times is an accurate rendering of the experience of the Japanese capital.

13 november 2002. I read that it was Rousseau in his Confessions who invented the notion of the self as an “inner” reality, unknown to those around us. It is now so ingrained, and used to create such bad faith, that I thought it had occurred much earlier.

There is a quote, too. If he did not hide this real self, then he would have to show himself “not just at a disadvantage but as completely different from what I am.” It was the disadvantage he was thinking of, hence his deciding that he was something else.

The Japanese (and many other Asian folk) have escaped this. There is no hidden and real self. Rather, the social self and the individual self are twins, living happily side-by-side, though occasionally quarreling. When getting along together, the social self is called tatemae and the personal is called honne and the combination is in the West called hypocrisy. When not getting along the social self is called giri (obligation) and the individual is called ninjo (inclination), and all of Japan’s drama is made up of the consequences.

14 november 2002. Walking down the street with Paul [McCarthy] and Ed [Seidensticker], Japan specialists both, we see a youth approaching us. “Oh,” says Paul, admiringly. “Now that’s attitude!”

What he is approving in the slovenly young is the way this schoolboy has altered his uniform. His shirt is open, the coat buttoned wrong, his pants pulled down so that the belt is far below the navel, and the crotch sways.

“No,” says Ed. “That’s fashion.”

16 november 2002. What do I want to be when I grow up? An attractive role would be that of the bunjin. He is the Japanese scholar who wrote and painted in the Chinese style, a literatus, something of a poetaster—a pose popular in the eighteenth century and typified by Yosa Buson, and right now by my friend Kajima Shozo. I, however, would be a later version, someone out of the end of Meiji, who would pen elegant prose and work up flower arrangements from dried grasses and then encourage spiders to make webs and render it all natural.

The bunjin is useless, knows nothing of commerce and politics, tends to be something of a dandy, and yet in his own way strives after truth. Art is for its own sake, but it also has a moral purpose. It makes one a better person. Privately he is heterodox, and here history is mostly silent.

This budding bunjin, myself, writes in English rather than Chinese, is a talented dilettante in almost everything, but a scholar in his field nonetheless. For him, art is a moral force and he cannot imagine a life without it—but art does not mean pictures (though he paints) but, rather, everything—fiction, poetry, drama, music, and films. He is also the kind of casual artist who, after the day’s work is done, descends into his pleasure park and dallies.

18 november 2002. I look out at the band shell. Only seven in the morning, but a long and ragged line. The jobless, homeless, waiting. In a few hours the evangelists will come and open the gates. In they will go, all of them, hundreds by then, and then the gates will be shut and locked. The seventh-day people will evangelize them with hallelujahs for an hour or two and then, having saved their souls, will hand out the rice-balls that are the reason the congregation gathered. And no one complains. The reason I know this is that one of the congregation told me. And this was not in complaint.

24 november 2002. Overnight, frigid autumn. North wind—that harsh edge remembered from winter—and shadows fading as cold clouds cover the sun. Why then, as I look out over the ruins of the great lotus pond, this sudden feeling of pleasure, of contentment?

It is because I am observing a great seasonal change, because I am here to do so, and to do so in comfort. It is because I am old and have many of the advantages of age.

I no longer care what people I don’t know think of me. And I take the opinion of those whom I do know lightly. I am no longer afraid of empty surmises. I am freed of the tyranny of my loins, if not yet from that of the loins of others. I am no longer afraid of my future since my future is already here, and my seventy-eighth year is my happiest yet.

25 november 2002. Ginza. I look about me. Not a sign of traditional Japaneseness. And to expect it would be like expecting powdered wigs in Philadelphia. Yet search we do, we foreigners. But since no one looks for colonial attributes in the U.S.A. why look for kimono in Japan?

One reason is that we occasionally see them. Another is that the Japanese make a big fuss about their traditional “heritage.” Yet another is that the past is centuries deep in Japan, and though erosion is swift and the water is rising, islets of tradition still float by.

Japan started late in the business of being modern. Before that it was timeless, a flat expanse with occasional eddies of modification. Consequently there is a backlog of tradition. But being traditional is nothing that inspires a contemporary young Japanese. Indeed no distinction is made between now and then, and if something old is useful it will be incorporated with no consideration, and if not it will be tossed out.

What I had thought a wall between the Japanese and the foreign no longer exists. And any barrier between then and now has been destroyed as well. And why not? This has gone on for centuries, and the destruction of tradition is a part of tradition itself. We do not remark on this in countries with shallow histories, only those with deep ones.

26 november 2002. In this signaling system that is life we must examine our own earpieces before we use our mouthpieces. We must learn to distrust ourselves, our own apparatus. Instead of assuming that the other made a mistake, we should at least admit the possibility that we did. This is particularly necessary in ascribing motives. How many times have I erred—allowing my agenda or my paranoia to garble the message?

Since my life has been spent in translating, in comparing and judging, my opportunities for error have been more than for many. Years ago, I was attempting to bend a younger person to my ends and he used a word I did not know that ended in kusai, a word I only knew as “stinking,” “putrid,” and so on. I at once took this as an insult and stalked off. Later, I heard the word again and this time recognized it as terukusai, a simple phrase meaning, “I’m embarrassed.”

28 november 2002. Student eating sandwich on the subway. Egg salad, I think. Big Adam’s apple bobbing above a celluloid collar. Very intent on delicate task, egg salad being what it is, and not a glance for those around him, no indication that he is not at home alone.

That is the difference. Even five years ago there would have been some concern at being thus seen consuming. A lapse of decorum—that is how it would be viewed. And still is sometimes. An older woman across from the youth is regarding the spectacle (some egg salad has just dropped onto that black gabardined lap) with a cold gaze. But she will die, this old woman, and the youth will grow to manhood and middle age.

The young may still talk about being ashamed or embarrassed, but this is merely a conversational ploy. No one under twenty feels the kind of social restraint once standard. Now not only does youth eat and drink in full view, but they also (boys and girls alike) pluck eyebrows and pop pimples. Also (just girls this time) put on full make-up in public—lipstick, rouge, and mascara.

Is this a Good Thing? I find it difficult to become as indignant as does the old lady, because it argues for a certain freedom which the young did not before express. Also I remember that the old lady’s generation (the men at any rate) pissed freely in the street, something today’s youth would not think of doing.

30 november 2002. Fumio for dinner. His birthday, his fifty-third. We met when he was twenty. Now, passion long spent, we are good friends, meet every week or so, and take a selfless interest in each other. I ask about his daughter, Haruka, and he asks about Dae-Yung, the son who took his place.

Over our tandoori chicken he asks me if I was ever interested in someone my equal. Since this was in Japanese he could ask it, no matter how strange it now sounds in English. I suppose it could be translated to mean had I ever “fallen in love” with anyone with the same “general interests,” that is, caste/class. In any event the answer is no.

My interests are entirely in differences. The beloved other has to be all things I am not, though I might wish to have been. Dae-Yung, a soccer champ, not interested in books or movies, straight, much more interested in action than in cogitation.

I ask Fumio about himself. Oh, no, for him it is similarities that attract. His wife, for example. Or me. Now wait just a minute, I thought. How come his difference attracted me, and my similarity attracted him?

As though I had said it aloud, he smiled, put down his fork, and said, “Maybe I was not much like you at first, but I became like you. You had more influence on me than anyone else. You didn’t see how much I had grown like you, and when you did we stopped making love and became friends instead.”

I had not known that before.

3 december 2002. On the plane coming back from Korea I sit across the aisle from Kitano Takeshi. We are both returning from the Pusan Film Festival. Now he has opened a large, blank-paged notebook, the kind used in primary school, and is scribbling in it, the writing large, unformed. He is creating his new film script.

This is the way he always works. He fills notebook after notebook, and these he presents to his associates. They all sit down and read them and then cobble together a scenario. After Kitano approves it, production begins. Filming is accomplished in an analogous manner. Something shot is inspected. If everyone agrees, it is used. If not it is discarded and the scene is rarely re-shot.

He nods as he writes, apparently agreeing with what his hand is doing, and then starts on a new page. There are many ways to create and this is one of them. Not perhaps the best, but one that fits Japan, where corporate accomplishment is so common. But as I watch his studious profile, observe his careful avoidance of all those staring (me included) at one of the most famous men in Japan, I recognize what he reminds me of—a diligent student doing his homework.

4 december 2002. Ian [Buruma] calls from London. He is writing about me for the New York Review of Books and wonders how to handle the subject of homosexuality. Cannot leave it out, wonders how to put it in. So do I—I remember Auden: “A capacity for self-disclosure implies an equal capacity for self-concealment.”

Possibilities: Not “gay”—gay is a lifestyle now, not a sex style. And not “queer,” which I otherwise like, since it has now been taken over by academe. “Faggot” might be misunderstood, and “homosexual” is just too solemn, a po-faced word bristling with medical associations.

Ian does not want to use terms like “preferences,” “lifestyles,” etc., because they are euphemisms. Perhaps no word then. Words are half the trouble anyway. Instead, dramatize. He will think about how to do this, and I add that he might mention the advantages of homosexuality.

There is John Updike: “Perhaps the male homosexual, uncushioned as he is by society’s circumambient encouragements, feels the isolated, disquieted human condition with special bleakness: he must take it straight.” A quote that means several things. Many men finally settle for the fact that they had children and this becomes why they are here—this is something that many women do, too. There is family life to sustain everyone except those who have never made families. In the end, the human condition wins out, to be sure. Maybe this is something that people with specialized roles know.