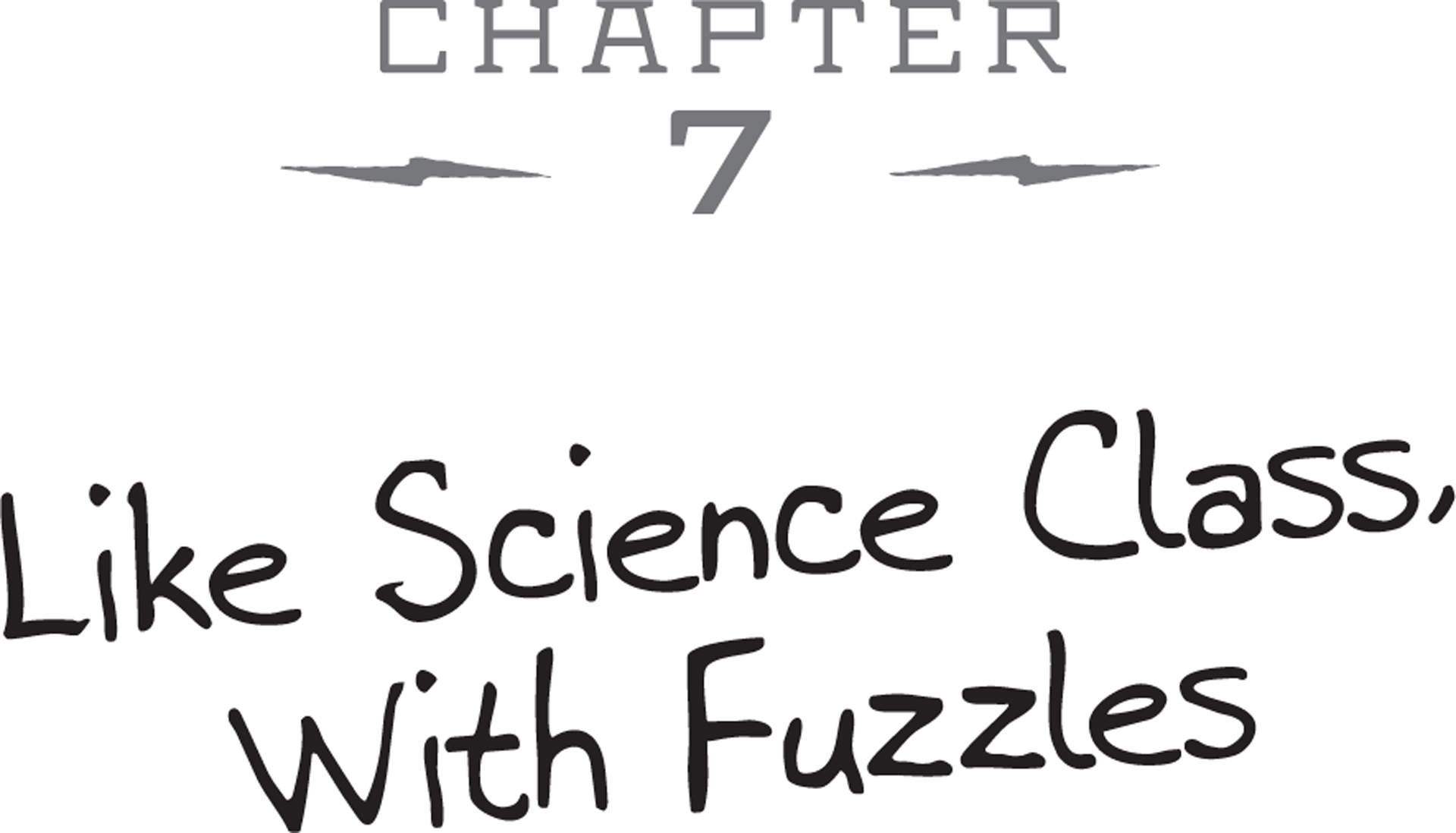

The next day, I sat in the lobby with Callie, watching a new litter of Bitterflunks. They bounced around like rubber balls, sometimes bouncing right out of their playpen. They were rather difficult to contain.

Callie was eating a giant bag of candy for lunch; she had to keep knocking the Bitterflunks out of the way as they aimed for the blue candies. Her tongue was a million different colors.

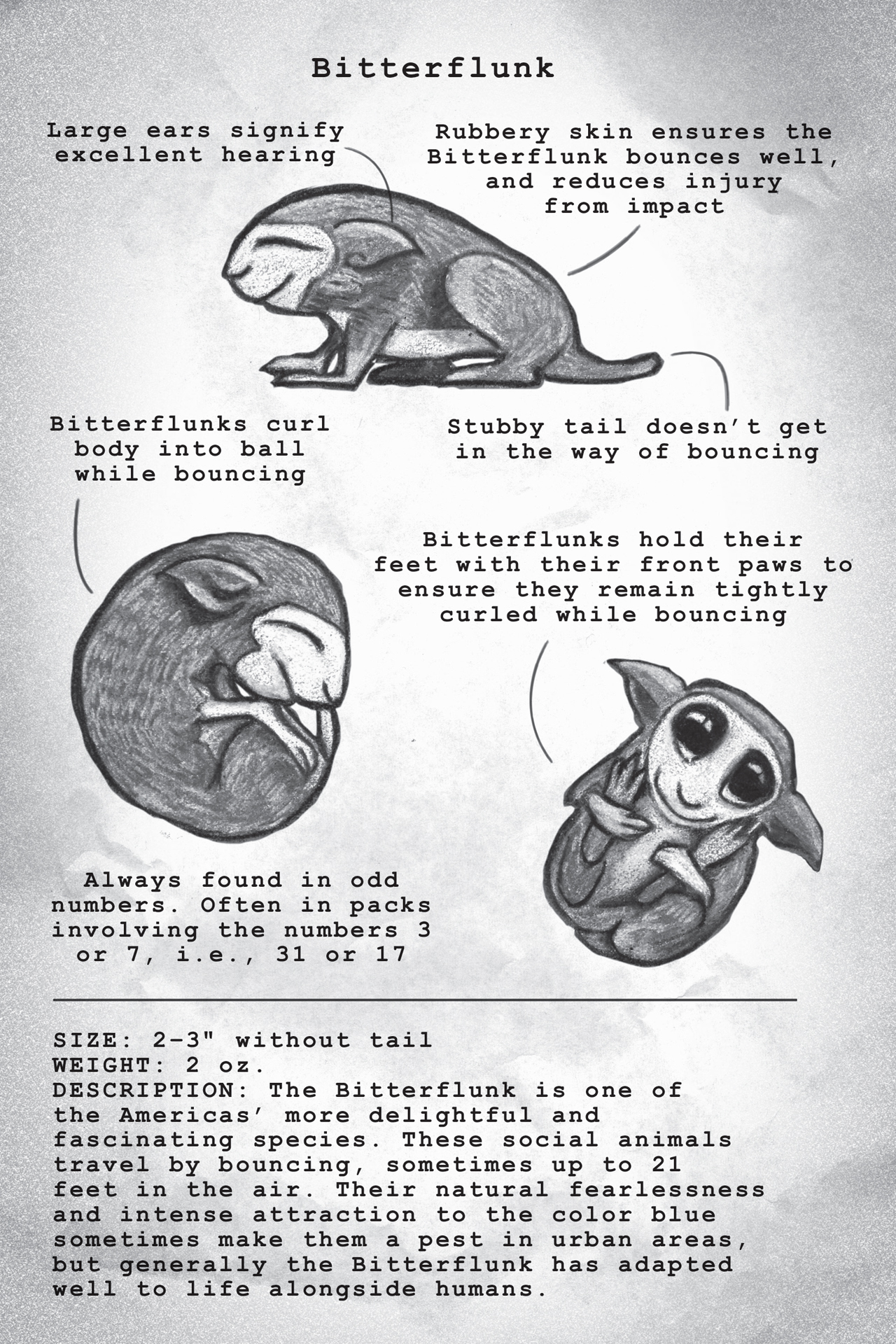

I was eating a spoon of peanut butter while going over my Fuzzle notes. I’d added quite a lot to the bare Fuzzle page in the Guide, thanks to my observation and to Callie’s information from the Internet. But I still didn’t know why they were here. Or why they kept coming. A new metal trash can had already been filled with today’s latest batch of Fuzzles. They liked being lumped up together, and now they hummed happily, harmonizing up and down the scale.

“Figure out how to get rid of those things yet?” Callie asked, swatting at a Bitterflunk. She missed, and it yelled “Wheeeeee!” as it rocketed to the ground. I caught the little creature as it bounced back up and tossed it back in the playpen. (“Wheeee!” it shouted again.) Callie appeared grudgingly respectful. “Nice one, Pip.”

“Thanks,” I replied, surprised. I handed the Guide to her so she could read what I’d added.

I didn’t get it. Fuzzles didn’t really eat—they just rolled over dust and digested it. Surely Cloverton dust wasn’t any better than dust anywhere else. They didn’t come here on a migration or to hibernate. And they were shy enough of people that it seemed like it would take a pretty good reason to make them move into a populated area.

Callie handed the Guide back to me. “I’m getting pretty sick of them.”

“Hey! They don’t mean to—”

“Oh, calm down. I don’t want them to get exterminated either. I just want them to stop showing up in my underwear drawer. What if they lit up my collection of Playbills?” She said that with wide eyes, like I would understand how serious it would be.

I didn’t understand, but I nodded anyway. “I know they’re dangerous. But it’s horrible—they’re just being Fuzzles! There has to be a way to convince them to leave.”

“Better figure it out fast. Mrs. Dreadbatch put flyers in everyone’s mailbox that said the exterminators will be here at the end of the week.”

That was barely any time at all!

I looked at the Bitterflunks, who were chasing one another in circles and shouting “Tag, you’re it! Tag, you’re it! Tag, you’re it!” even though no one actually seemed to be it. The Guide said Bitterflunks were pests too—but they were also pets. Maybe if people started thinking of Fuzzles as pets, they wouldn’t be so quick to want them exterminated. Maybe people would even start to want them around.

“Callie,” I said. “I have an idea!”

Callie looked worried.

I explained to her my thoughts on Fuzzles as pets. She looked more worried.

“A pet? That might burn your house down?” she asked.

“All pets have drawbacks,” I insisted. “Bitterflunks are always burrowing into walls, but people still keep them as pets. And tons of people have Fire-Breathing Manticores!”

“Tons of people think they can sing soprano too, but that doesn’t make them right,” Callie said. I put my hands on my hips, and she finally rolled her eyes. “All right, all right—let’s say we want to convince people these things are pets. What’s the hook? What makes people think ‘YES—I want a pet Fuzzle!’?”

I plucked two Bitterflunks out of my hair (“Tag, you’re it!” shouted both of them) and answered, “Let’s make a list.”

Callie insisted on being the list maker. I suspected it was because holding the clipboard made her feel very important. She used a different colored pen for each line.

Fuzzles are great pets because:

1)Cute

2)Don’t smell (not counting the smoke)

3)Don’t bite

4)Eat dust (cuts down vacuuming?)

Then we made a list of why they were bad pets—the things we needed to overcome. It was a short list.

Fuzzles are bad pets because:

1)Burst into flame (constantly)

2)Destroy your underwear

“Callie!” I said. “Those are sort of the same thing. You can’t count the underwear as a whole second thing.”

“Tell that to my underwear,” Callie said, rolling her eyes. She tapped her pen on the edge of the clipboard. “So far, the bad list outweighs the good one. Maybe they can be trained? You know, to not catch on fire. Plenty of animals can bite, but they’re trained not to.”

“That’s a great idea, Callie!” I said.

I must have laid on the enthusiasm a little too thick, because she replied, “You don’t have to sound so surprised. I do know something about animals. All right, let’s train one.”

I’d never really trained an animal before, but I knew the basic idea. We had to reward them for behavior that we liked.

“What do Fuzzles like?” Callie asked. “We can’t just throw dust at them.”

“Tickling,” I said. “We can tickle them when they do the right thing.”

We chose a small Fuzzle from today’s trash can load, figuring that if it were a baby, perhaps it would be easier to train. Then we sat down in the middle of the clinic lobby with the Fuzzle in a frying pan between us. It zipped up and down the sides like a skateboarder on a ramp—I guess it liked the slippery frying-pan surface.

I said, “Now we need something that might startle it. Not something too loud at first. And then, when it doesn’t catch fire, we’ll tickle it.”

“And if it does catch fire?” Callie asked. “Do we punish it?”

“No, no. Only—what do you call it? Positive reinforcement.” I held up the lid to the pan. “We’ll just wait for it to calm down. Now, what can we do that might startle—”

“I’ve got this.” Callie cracked her knuckles and gave me a smug look. “I needed to practice my scales anyway. Ready?” Taking a big breath, she began to sing, “Do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-doooooooooo.”

In response, the Fuzzle rolled in circles around the frying pan. It didn’t burst into flame, so I tickled it. As it hummed, I grinned up at Callie. “Great! Can you do it any louder?”

“Oh, please! Do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-doooooooo!”

“What is all this noise? I’m trying to nap!” a gruff voice snapped from behind the desk. Bubbles poked his head around the corner, saw Callie, and sighed heavily. Ruffling his feathers, he asked, “Do you suppose Fuzzles would make good earmuffs?”

“I think that’s a little risky,” I replied. Luckily, Callie didn’t hear me, because she was singing again, a little louder this time. I tried to tickle the Fuzzle, but it didn’t seem to be paying much attention to me. It rolled away from my fingers—

“Do-re-mi—”

The Fuzzle rolled in smaller and smaller circles. Faster and faster circles too.

Callie got louder.

Bubbles covered his ears with his wings.

“Do-re-mi—”

“Callie, wait, don’t get any louder!” I said, but her eyes were shut and her hands thrown out dramatically. She took a deep breath—

“Fa-sol-la-ti-DOOOOOOOOOO!”

The Fuzzle shivered at the last note and then, pow, it burst into flames so fast that I couldn’t even get the lid on the pan in time. Smoke curled up to the ceiling, Callie scrambled backward, and Bubbles laughed.

“Don’t blame the Fuzzle,” Bubbles said. “Callie’s singing makes me want to explode too.”

“Maybe they just take a while to train,” I said hopefully, waving the smoke away with the pan lid as the Fuzzle calmed. “One session doesn’t really count.”

Callie coughed meaningfully. “Get real, Pip. No one’s going to risk a fire every time they turn on the radio or slam a door, even if the Fuzzle can eventually be trained. Fire-Breathing Manticores almost never turn into flameballs. Fuzzles always turn into flameballs.”

I tried to think of a positive spin. “But … but … maybe that can be useful though! People need fire, don’t they?”

Callie gave me a long look as she added two lines to the bad list—

Fuzzles are bad pets because:

1)Burst into flame (constantly)

2)Destroy your underwear

3)Can’t be trained

4)Don’t appreciate fine music

I thought that fourth thing was a matter of opinion, but I didn’t say anything. I dragged my backpack closer. I scooped the Fuzzle out of the frying pan and into one of the backpack’s outside pockets. It seemed enough like an underwear hammock that the Fuzzle should be happy.

“See? Maybe Fuzzles could be great for camping!” I suggested brightly. “You could backpack with them, like this, and then when you stop to make a camp, you can just startle them and boom! You’ve got a campfire!”

“Or boom, your backpack is on fire,” Callie said.

“Well, you wouldn’t just say ‘boom’ until you needed—”

“No—your backpack is on fire,” Callie said, pointing. I rustled the backpack off and sure enough, the Fuzzle was smoldering a hole right through the outside pocket. When the hole had burned big enough, the Fuzzle rolled out onto the clinic floor, leaving a trail of melted linoleum behind it.

This was not going well.

By the time Aunt Emma emerged from the exam rooms for her lunch break, Callie had added a lot more to our lists.

Fuzzles are bad pets because:

1)Burst into flame (constantly)

2)Destroy your underwear

3)Can’t be trained

4)Don’t appreciate fine music

5)Like to be in groups, so you can’t really have just one

6)If you look away for a minute, they hide in some small place

6a)Like your underwear drawer

7)The smoke smells really bad after a while

8)The batteries in your smoke detector will be dead by the end of the day

“What’s this?” Aunt Emma asked, brushing past the front desk. Callie and I were using the Fuzzles’ fire to roast marshmallows right in the middle of the lobby. Using Fuzzles to help roast marshmallows was the only thing we’d been able to add to the good list.

“Fuzzle training. Want a marshmallow?” I held up my marshmallow skewer to her—the one on the end was perfectly browned.

Aunt Emma accepted it. Through the marshmallow, she asked, “Any luck?”

Callie shook her head. “Nope. They just—hey!” she said when the Fuzzle went out. She waved her marshmallow skewer over it, then sang, “Do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do!”

The Fuzzle burst back into flame. Callie stuck the marshmallow into the fire, then waited till it was nearly burned to a crisp to pull it off and eat it.

“Well, this is a cool idea, at least!” Aunt Emma said.

With a snort, Callie handed her mother the bad list. Aunt Emma’s eyes widened. I couldn’t tell if she was impressed or worried about all the experimenting we’d done.

“I just thought if we could prove they were trainable, people would think of them as pets, not pests,” I said.

“It happens sometimes, Pip,” Aunt Emma said kindly. “People are always trying to make pets out of animals, and sometimes they’re just happier in the wild.”

“The wilds of my underwear drawer,” Callie huffed.

“I suspect that if the Fuzzles could talk, they’d tell you their habitat was here long before your underwear drawer. Or this clinic! Or Cloverton!” Aunt Emma pointed out. “I wish they could talk, actually—maybe they’d be able to talk some sense into Mrs. Dreadbatch!”

We all sighed. None of us believed anyone could talk sense into Mrs. Dreadbatch.