As Nadeem’s coach, I had the luxury of interviewing his colleagues and direct reports and hearing the unvarnished truth about his behavior. I was accumulating valuable feedback that Nadeem wasn’t in a position to get.

A little prodding is required at the start of each interview, because people are essentially decent and kind. They don’t want to hurt a colleague’s feelings, or appear catty. Sometimes they’re afraid of retribution, despite the cloak of anonymity I provide. But eventually people realize that this process is in everyone’s best interest, so they tell the truth.

The interviewees almost always focus on my client’s good or bad behavior that they have experienced personally. Interviewees rarely mention the environment in which that behavior occurs. I have to press for that information. When does he act like this? With whom? Why? Eventually I get useful answers. The interviewees begin describing my client behaving badly in situational terms such as when he’s “under pressure” or “racing a deadline” or “juggling too many balls.” Slowly it dawns on them how profoundly the environment affects behavior.*

That’s what happened with Nadeem’s feedback. His colleagues described Nadeem’s defensiveness in meetings. But it took insistent questioning before they associated it exclusively with Simon’s presence in the room.

Feedback—both the act of giving it and taking it—is our first step in becoming smarter, more mindful about the connection between our environment and our behavior. Feedback teaches us to see our environment as a triggering mechanism. In some cases, the feedback itself is the trigger.

Consider, for example, all the feedback we get when we’re behind the wheel of a car, how we ignore some of it, and why only some of it actually triggers desirable behavior.

Say you’re driving down a country road at the posted speed limit of 55 mph, approaching a village. You know this because a half mile outside the village a sign says, SPEED ZONE AHEAD 30 MPH. The sign is just a warning, not a command to slow down, so you maintain your speed. Thirty seconds later, you reach the village, where the sign says, SPEED LIMIT 30 MPH. You may comply, but if you’re like most drivers you’ll maintain your speed (or slow down slightly) because you’ve been driving on autopilot in a 55-mph environment and it’s easier to continue doing what you’re doing than to stop doing it. Only if you see a manned police car monitoring motorists’ speeds will you comply with the mandated 30 mph—because a police officer handing out speeding tickets represents an unwanted consequence to you.

Every community in the developed world has to deal with speeding drivers putting citizens at risk. For years drivers in my neighborhood north of San Diego ignored the speed signs that told them to slow down as they transitioned from the 65 mph on the San Diego Freeway to 45 mph on the main commercial thoroughfares and 30 mph in school zones and residential neighborhoods. Nothing worked to decrease speeding, not even a greater police ticketing presence, until town officials installed radar speed displays (RSDs)—a speed limit sign posted above a digital readout measuring “Your Speed.” You’ve probably seen them on your town’s streets near a school or as you approach a tollbooth. If the RSD says you’re speeding, you’ve probably stepped on the brake immediately. As sensor technology becomes cheaper, RSDs are being more widely used so the data about their effectiveness is deeper and more reliable. Speed limit compliance increases 30 to 60 percent with RSDs—and the effect lasts with drivers for several miles beyond the RSD.

Radar speed displays—also called driver feedback systems—work because they harness a well-established concept in behavior theory called a feedback loop. The RSDs measure a driver’s action (that is, speeding) and relay the information to the driver in real time, inducing the driver to react. It’s a loop of action, information, reaction. When the reaction is measured, a new loop begins, and so on and so on. Given the immediate change in a driver’s behavior after just one glance at an RSD, it’s easy to imagine the immense utility of feedback loops in changing people’s behavior.

A feedback loop comprises four stages: evidence, relevance, consequence, and action. Once you recognize this, it’s easy to see why the radar speed displays’ exploitation of the loop works so well. Drivers get data about their speed in real time (evidence). The information gets their attention because it’s coupled with the posted speed limit, indicating whether they’re obeying or breaking the law (relevance). Aware that they’re speeding, drivers fear getting a ticket or hurting someone (consequence). So they slow down (action).

I’m basically initiating a feedback loop at the start of any one-on-one coaching assignment. My first stage with Nadeem, for example, was presenting him with the evidence—the interviews that I had compiled and shared with him. The stories about his behavior were emotionally resonant for Nadeem because they were coming from people he respected. They had unequivocal relevance. The loop’s third stage, consequence, was patently obvious: if Nadeem didn’t change his behavior around Simon, he was not behaving as the team member he wanted to be, and potentially damaging his career. It wasn’t a difficult choice. Once the evidence, relevance, and consequence were firmly lodged in Nadeem’s mind, he had sufficient clarity to close the loop with action. He would ignore Simon’s provocateuring ways. He would resist sparring with Simon. He would win Simon over and, in turn, reclaim his colleague’s respect and his own reputation. Each time he displayed restraint with Simon, he got a little better, a little more confident that he was on the right track and making a better impression on his colleagues. And the loop could run again, a prior action leading to a new action nudging Nadeem ever closer to his goal.

This is how feedback ultimately triggers desirable behavior. Once we deconstruct feedback into its four stages of evidence, relevance, consequence, and action, the world never looks the same again. Suddenly we understand that our good behavior is not random. It’s logical. It follows a pattern. It makes sense. It’s within our control. It’s something we can repeat. It’s why some obese people finally—and instantly—take charge of their eating habits when they’re told that they have diabetes and will die or go blind or lose a limb if they don’t make a serious lifestyle change. Death, blindness, and amputation are consequences we understand and can’t brush aside.

I don’t want to get lost in theory over feedback loops. They’re complex and can be applied to almost anything. Photosynthesis is a feedback loop between the sun and plants. Owners of hybrid cars (like me in my Ford C-Max) are in a feedback loop when they obsessively check their dashboard’s gas consumption display and adjust their driving to maximize gas mileage (they’re called “hypermilers”). The Cold War arms race, with East and West escalating weaponry to match each other, may be the most expensive feedback loop in history.

For our purposes, let’s focus on the feedback loop created by our environment and our behavior.

As a trigger, our environment has the potential to resemble a feedback loop. After all, our environment is constantly providing new information that has meaning and consequence for us and alters our behavior. But the resemblance ends there. Where a well-designed feedback loop triggers desirable behavior, our environment often triggers bad behavior, and it does so against our will and better judgment and without our awareness. We don’t know we’ve changed.

Which brings up the obvious question (well, obvious to me): What if we could control our environment so it triggered our most desired behavior—like an elegantly designed feedback loop? Instead of blocking us from our goals, this environment propels us. Instead of dulling us to our surroundings, it sharpens us. Instead of shutting down who we are, it opens us.

To achieve that, we first have to clarify the term trigger:

A behavioral trigger is any stimulus that impacts our behavior.

Within that broad definition there are several distinctions that improve our understanding of how triggers influence our behavior.

1. A behavioral trigger can be direct or indirect.

Direct triggers are stimuli that immediately and obviously impact behavior, with no intermediate steps between the triggering event and your response. You see a happy baby and smile. A child chases a basketball into the street in front of your car and you instantly hit the brakes. Indirect triggers take a more circuitous route before influencing behavior. You see a family photo that initiates a series of thoughts that compel you to pick up the phone and call your sister.

2. A trigger can be internal or external.

External triggers come from the environment, bombarding our five senses as well as our minds. Internal triggers come from thoughts or feelings that are not connected with any outside stimulus. Many people meditate to dampen the internal trigger they refer to as an “inner voice.” Likewise, the idea that inexplicably pops into your head when you’re alone musing on a problem is an internal trigger inspiring you to take action. Its origin may be a mystery, but if it stimulates behavior, it’s as valid as any external prompt.

3. A trigger can be conscious or unconscious.

Conscious triggers require awareness. You know why your finger recoils when you touch the hot plate. Unconscious triggers shape your behavior beyond your awareness. For example, no matter how much people talk about the weather they’re usually oblivious about its triggering influence on their moods. Respondents to the question “How happy are you?” claimed to be happier on a perfect weather day than respondents to the same question on a nasty weather day. Yet when asked, most respondents denied the weather had any impact on their scores. The weather was an unconscious trigger that changed their scores but was outside their awareness.

4. A trigger can be anticipated or unexpected.

We see anticipated triggers coming a mile away. For example, at the beginning of the Super Bowl, we hear the national anthem and expect raucous cheering as it ends. The song triggers a predictable response. (It works the other way, too. We know that our demeaning language will trigger other people’s anger so we avoid it.) Unanticipated triggers take us by surprise, and as a result stimulate unfamiliar behavior. My friend Phil did not see his fall down the stairs coming, but the fall triggered a powerful desire to change.

5. A trigger can be encouraging or discouraging.

Encouraging triggers push us to maintain or expand what we are doing. They are reinforcing. The sight of a finish line for an exhausted marathon runner encourages him to keep running, even speed up. So does the appearance of a rival runner at his side about to pass him. Discouraging triggers push us to stop or reduce what we are doing. If we’re talking in a theater, an annoyed “Ssshhh” from an audience member triggers an awareness that we’re disturbing people—and we stop talking.

6. A trigger can be productive or counterproductive.

This is the most important distinction. Productive triggers push us toward becoming the person we want to be. Counterproductive triggers pull us away.

Triggers are not inherently “good” or “bad.” What matters is our response to them. For example, well-meaning and supportive parents can trigger a positive self-image for one child yet be viewed as “smothering” by another child. Parents of two or more children know this all too well. Equal levels of devotion and caring can trigger gratitude in one child and rebellion in another. Same parents. Same triggers. Different responses.

To fully appreciate the reason for this, it’s helpful to take a closer look at these last two dimensions of triggers—encouraging or discouraging, productive or counterproductive. They express the timeless tension between what we want and what we need. We want short-term gratification while we need long-term benefit. And we never get a break from choosing one or the other. It’s the defining conflict of adult behavioral change. And we write the definitions.

We define what makes a trigger encouraging. One man’s treat is another man’s poison. The sudden appearance of a bowl of Rocky Road ice cream may trigger hunger in us and disgust in our lactose-intolerant dinner companion.

Likewise, we define what makes a trigger productive. We all claim to want financial security; it’s a universal goal. But when we get our year-end bonus, some of us bank the money while others gamble it away over a weekend. Same trigger, same goal, different response.

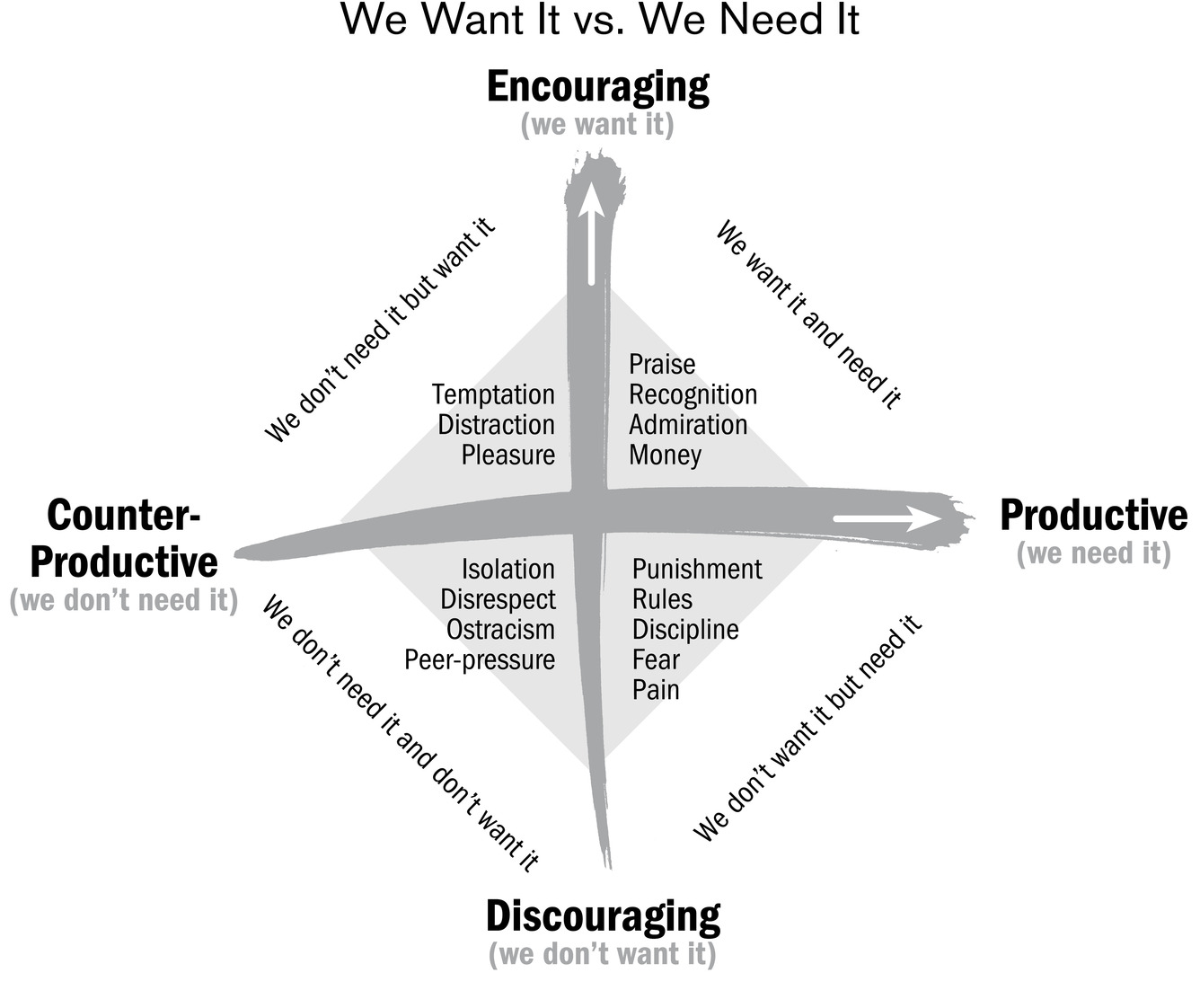

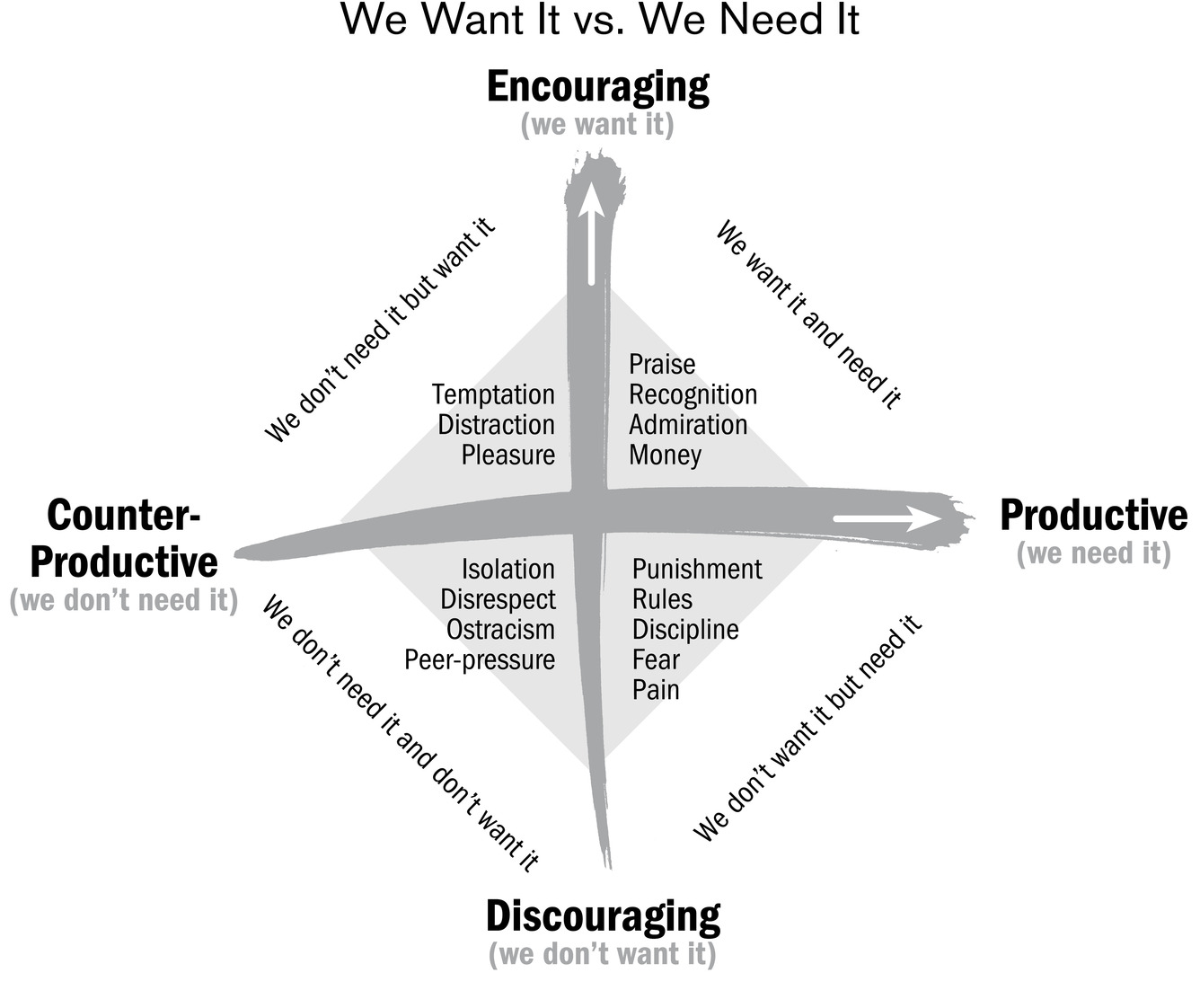

We can illustrate this conflict in the following matrix where encouraging triggers lead us toward what we want and productive triggers lead us toward what we need. If only our encouraging triggers and productive triggers were the same. It can happen. It’s the ideal situation. Unfortunately, what we want often lures us away from what we need. Let’s take a closer look.

We Want It and Need It: The upper right quadrant is where we’d prefer to be all the time. It is the realm where encouraging triggers intersect with productive triggers, where the short-term gratification we want is congruent with the long-term achievement we need. Praise, recognition, admiration, and monetary rewards are common triggers here. They make us try harder right now and they also reinforce continuing behavior that drives us toward our goals. We want them now and need them later.

We Want It but Don’t Need It: The paradoxical effect of an encouraging trigger that is counterproductive comes to a head most tellingly in the upper left quadrant. This is where we encounter pleasurable situations that can tempt or distract us from achieving our goals. If you’ve ever binge-watched a season or two of a TV show on Netflix when you should be studying, or finishing an assignment, or going to sleep, you know how an appealing distraction can trigger a self-defeating choice. You’ve sacrificed your goals for short-term gratification. If you’ve ever taken a supervisor’s compliment or a client’s reassurances as an excuse to ease up a little bit, you know how positive reinforcement can set you back rather than propel you ahead.

We Need It but Don’t Want It: The lower right quadrant is a thorny grab bag of discouraging triggers that we don’t want but that we know we need.

Rules (or any highly structured environment) are discouraging because they limit us; they exist to erase specific behaviors from our repertoire. But we need them because obeying rules makes us do the right thing. Rules push us in the right direction even when our first impulse is to go the other way.

Fear—of shame, punishment, reprisal, regret, disrespect, ostracism—is a hugely discouraging trigger, often appearing after we fail to follow a rule. If you’ve ever been dressed down in public by a high-ranking manager, you know it’s something you don’t want to repeat—which makes it a powerful motivator to stay true to your long-term goals.

Even quirky discipline can be found here. When I fine my clients twenty dollars for cynicism and sarcasm, I’m introducing a discouraging trigger (it’s loss aversion, the concept that we hate losing one dollar more than we enjoy gaining two) that also aims to trigger productive behavior (that is, make people nicer).

Pain, of course, is the ultimate discouraging trigger: we immediately stop a behavior that hurts.

We Don’t Need or Want It: The lower left quadrant, where our triggers are both discouraging and counterproductive, is not a good place to be. It includes all the dead-end situations that make us miserable—and we can’t see any way out of them. It could be a toxic workplace or a violent neighborhood, the kinds of environment that trigger unhealthy behavior steering us away from our goals. There’s not much mystery to why these ugly environments trigger fatigue, stress, apathy, hopelessness, isolation, and anger. The only puzzle is why we choose to stay here instead of fleeing at high speed.

I’m not rigid or doctrinaire about these quadrants. Our experience is too rich and fluid to be contained in a theoretical box. Some triggers overlap or mutate, depending on how we respond, and move us from a bad place to a good one. Consider the triggering impact of peer pressure. An academically ambitious teen may be mocked and ostracized by his slacker classmates for studying hard and wanting to go to college. If he allows the peer pressure to discourage him from his goals, he’ll find himself in the unenviable lower left quadrant. On the other hand, if he resists the peer pressure and endures the ostracism, the isolation may focus him and steel his resolve. It gives him the discipline he needs. It may not be pleasant in the short term but it’s all the push he needs to shift to the lower right quadrant. Same trigger and goals, different responses and outcomes.

I find the grid useful as an analytical tool with my clients. It enables them to take inventory of the triggers in their lives, which, if nothing else, increases their awareness about their environment. More important, it reveals whether they’re operating in a productive quadrant. The right side of the matrix is where successful people want to be, moving forward on their behavioral goals.

Now it’s your turn. Try this modest exercise.

Pick a behavioral goal you’re still pursuing. We all have a few, from getting in shape to being a more patient parent to being more assertive around pushy people.

List the people and situations that influence the quality of your performance. Don’t list all the triggers in your day; that’s overkill given the hundreds, perhaps thousands of sensory and cerebral stimuli we encounter. Stick to the trigger or two that relate to one specific goal. Then define it. Is it encouraging or discouraging, productive or counterproductive?

Then chart the triggers to see if you’re on the right side. If you’re falling short of your goal, this simple exercise will tell you why. You’re getting too much of what you want, not enough of what you need.

You might learn that your best friend at work, the kind who drops by your desk several times a day and wants to join up regularly after work, is the trigger that distracts you from going home in time to see your kids. (You need to “fire” that friend for a while.)

You might learn that you regularly miss your early morning workout because you waste your wake-up hours on Facebook or checking emails. You need the former, want the latter obviously. (You need to rethink whether morning is your optimal time to work out.)

My hope for this exercise is that it 1) makes us smarter about specific triggers and 2) helps us connect them directly to our behavioral successes and failures.

I do it myself. For example, like half the men I know, I’d be happier if I were ten pounds lighter. I’ve believed this for thirty years. Yet in all that time I’ve done nothing about those last ten pounds. Why have I failed to become the person I want to be?

The grid provides an answer.

I’m not exposed to any encouraging triggers pushing me toward the goal. I only worry out loud about the weight with my wife, Lyda. But when I do so, she showers me with positive reinforcement. “You look fine,” she says. Encouraging words, but not the kind driving me in the right direction. She’s not lying to make me feel better. I’m not overweight, never have been. My suit size and waistline haven’t changed in decades. She’s reassuring me that my weight is “good enough.” So I tell myself, “She’s right. Why am I beating myself up over ten pounds no one notices?” As a result, I do nothing. I settle for the status quo.

I also don’t have any discouraging triggers pushing me toward the goal. No one’s shaming me or threatening to punish me about those last ten pounds. I haven’t set up any systems of rules or fines to nudge me toward this goal. I simply don’t exist on the right side of the matrix. And the right side is the only place to be for achieving behavioral change.

As insights go, locating myself on the wrong side of the matrix is a small and humbling lesson, reminding me that a trigger is a problem only if my response to it creates a problem. To lose the ten pounds, it’s up to me to escape the upper left quadrant where I prefer what I want to what I need. It’s my choice, my responsibility. It doesn’t solve the puzzle of achieving behavioral change, but it’s a start in the right direction.

This may be the greatest payoff of identifying and defining our triggers—as the occasional but necessary reminder that, no matter how extreme the circumstances, when it comes to our behavior, we always have a choice.