9. Finer Points of Clues: General

“I attempted yesterday’s Times crossword and managed to complete three clues – quid, Turgenev and courtier. I can only improve.”

Lord Archer, A Prison Diary

Now to some points that are unrelated to specific clue types.

1. Complex constructions

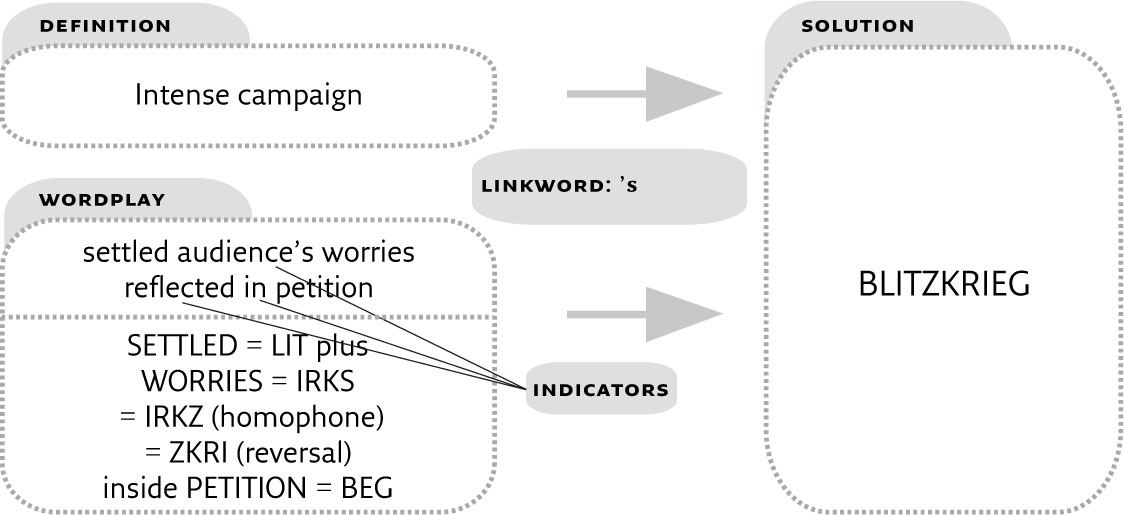

Until now we have been concerned with demonstrating how to solve clues that have one or two elements of trickery within them. Most clues do follow this pattern but should you be daunted by those which have even more? I’d say not at all: it’s still a question of decoding the separate elements, each of which will be signalled in its own way. Even if the word defined is an unusual one and the wordplay complex, you follow the indicators eventually to arrive at the solution. The complex clue is reserved usually for intractable words (as in the following example), for which the setter can find no alternative. Don’t worry if you find this too unreasonably difficult (I do, too!) as simplicity is the ideal of most setters – a clue like this is thankfully rare:

COMPLEX CLUE – SANDWICH INCLUDING REVERSAL AND HOMOPHONE: Intense campaign’s settled audience’s worries reflected in petition (10)

Fairly commonly, the linkword has to be taken as one form in the surface reading and a different form in the cryptic reading. In this example, the use of ’s means possessive pronoun in the former and is in the latter.

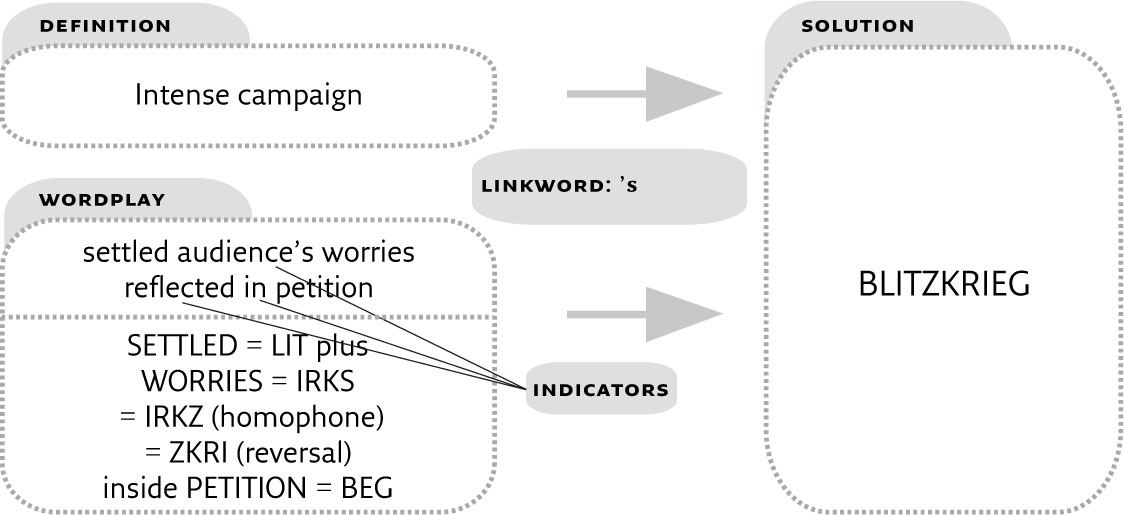

SANDWICH CLUE: Moll’s ‘leave it alone’ as bottom’s pinched (8)

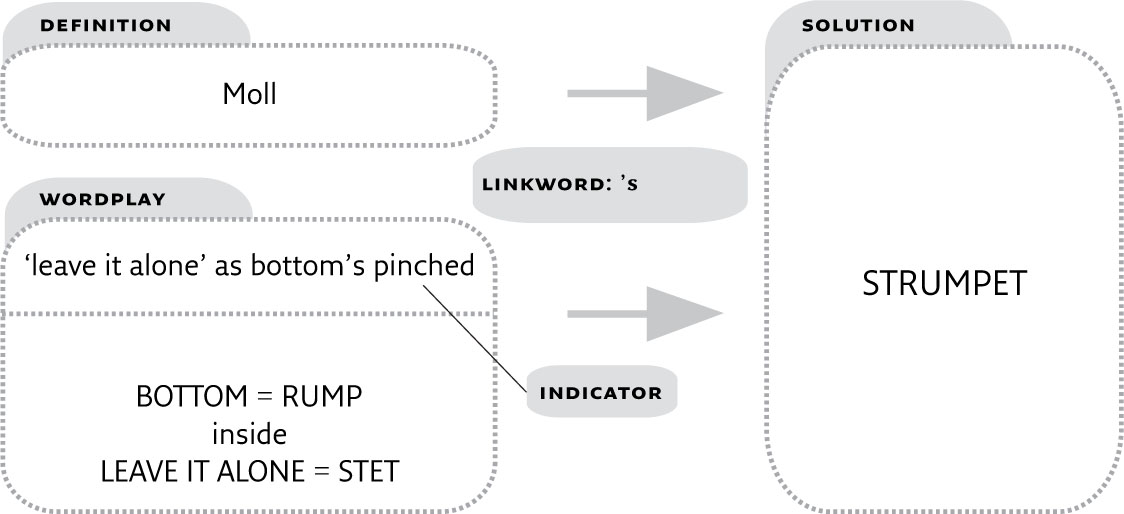

3. Punctuation: misleading

Apart from question marks and exclamation marks (see next paragraph), punctuation is by convention in all crosswords unreliable. This is especially confusing to beginners who have to be reminded that it may mislead and may have to be ignored. For example, as mentioned before, the components of an anagram can be split across a full stop or a comma.

ANAGRAM CLUE: Composition of Lennon, voice of pacifism (3-8)

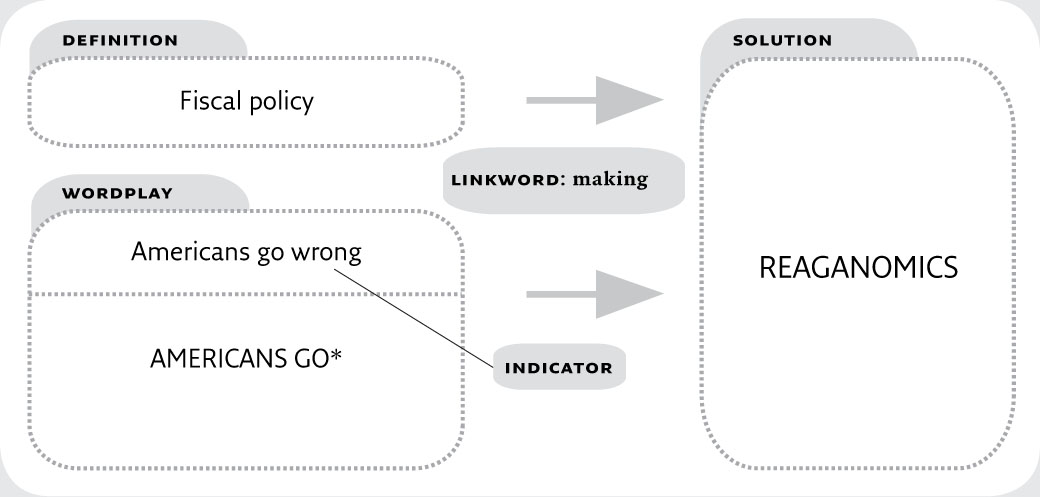

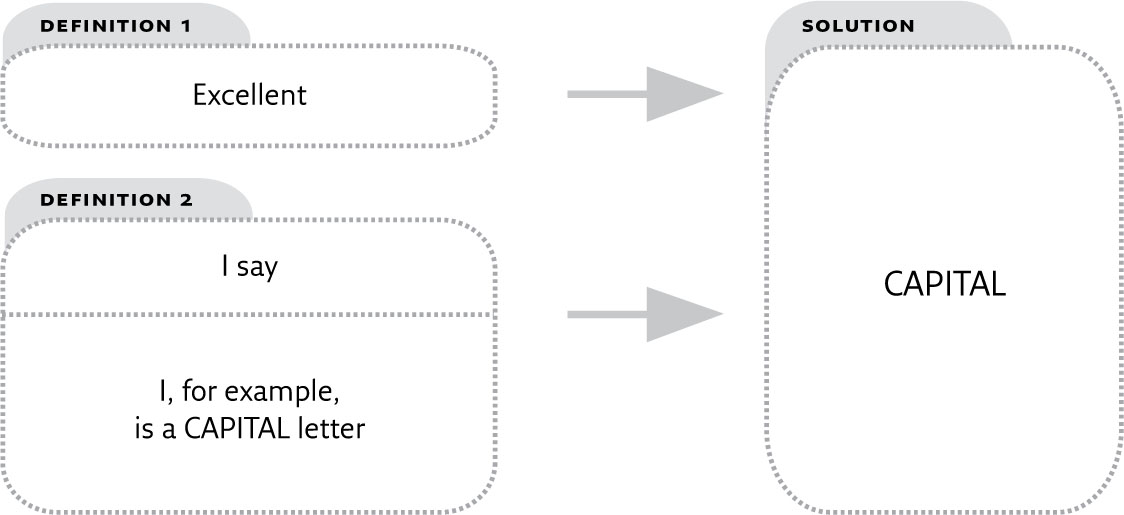

TOP TIP – DIRECTION OF LINKWORDS

Working out which way the linkword is pointing can be tricky. For example, while it is entirely normal (in normal English and crosswords) that from and leading to point to the answer from the preceding wordplay, the reverse may occasionally apply. The test is whether the wordplay stands for the definition: that is to say, it clearly and grammatically shows the process which gives the solution. By stretching the language, some linkwords such as get, gets, getting, makes or making can point either way. Here is an example:

ANAGRAM CLUE: Fiscal policy making Americans go wrong? (11)

You are required to think of the solution giving rise to the anagram fodder. The reverse order, as in my reworked clue below, would be more natural and is more likely to be found in the best puzzles.

ANAGRAM CLUE: Americans go wrong making fiscal policy (11)

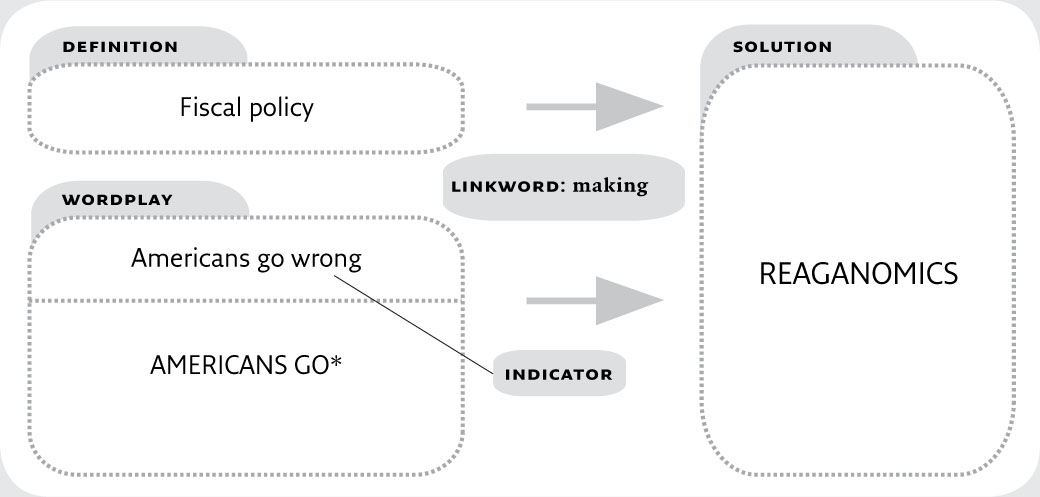

Or punctuation can mislead by separating the parts to be manipulated, as seen here:

ADDITIVE CLUE: Cold potato? Fine (5)

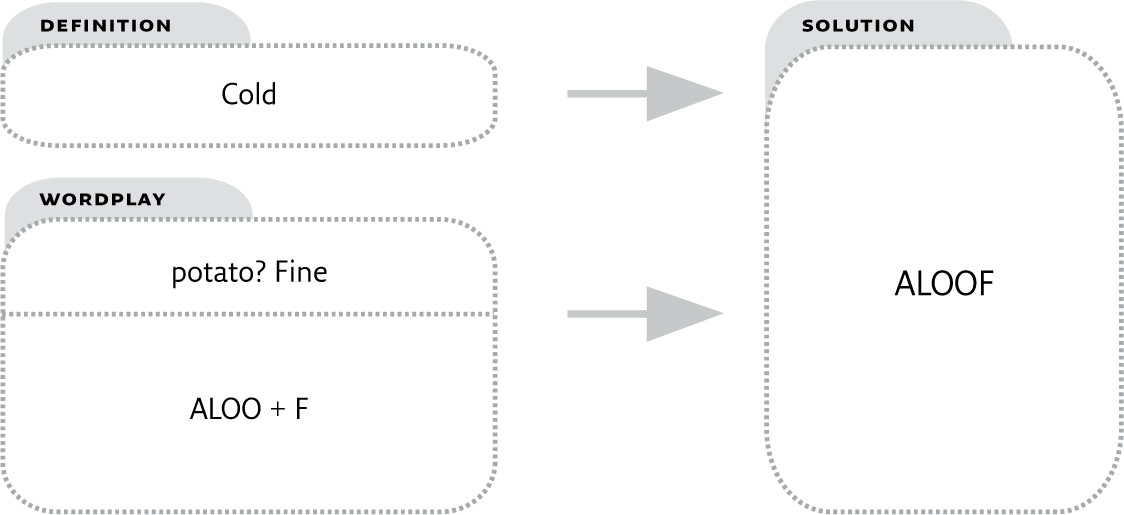

Punctuation can be omitted, too, as here where the comma required by the cryptic reading between the last two words (as in ‘I, say’) is not shown in the second definition:

DOUBLE DEFINITION CLUE: ‘Excellent’, I say (7)

4. Punctuation: not misleading

The exceptions when punctuation is there to help are mainly in these two cases:

• Question mark: as a hint that the solution either is slightly tenuous, or it’s an example of a group rather than a synonym. Thus apple to define fruit may well have a question mark.

TOP TIP – WHAT DO ELLIPSES IN CLUES MEAN?

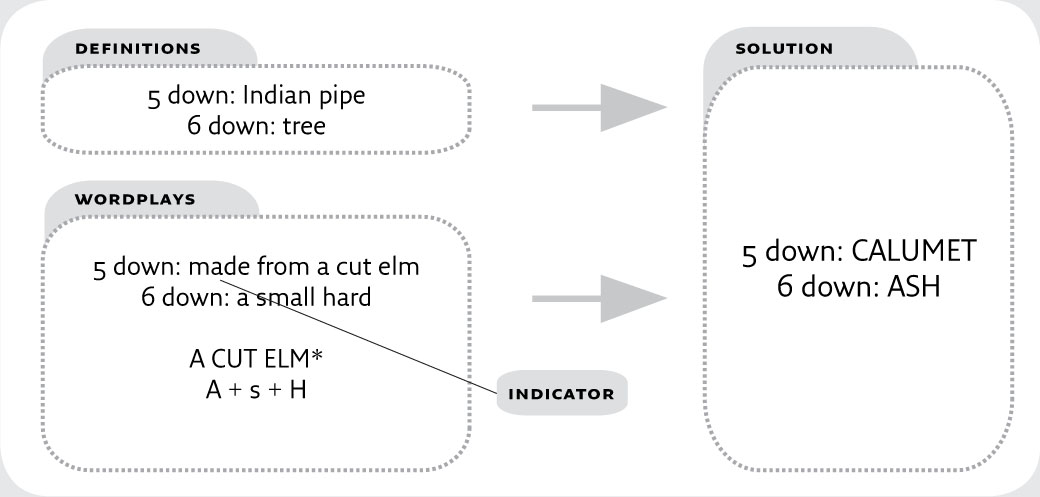

The answer is simple: it’s merely a way of connecting two clues (sometimes more) to present a longer than normal clue sentence, i.e. across the two clues. Each clue stands on its own with regard to definition and wordplay (even if one part references another). Here is an example in which the first is an anagram and the second an additive:

TWO CLUES LINKED BY ELLIPSES: 5 down: Indian pipe made from a cut elm… (7)

6 down: …a small hard tree (3)

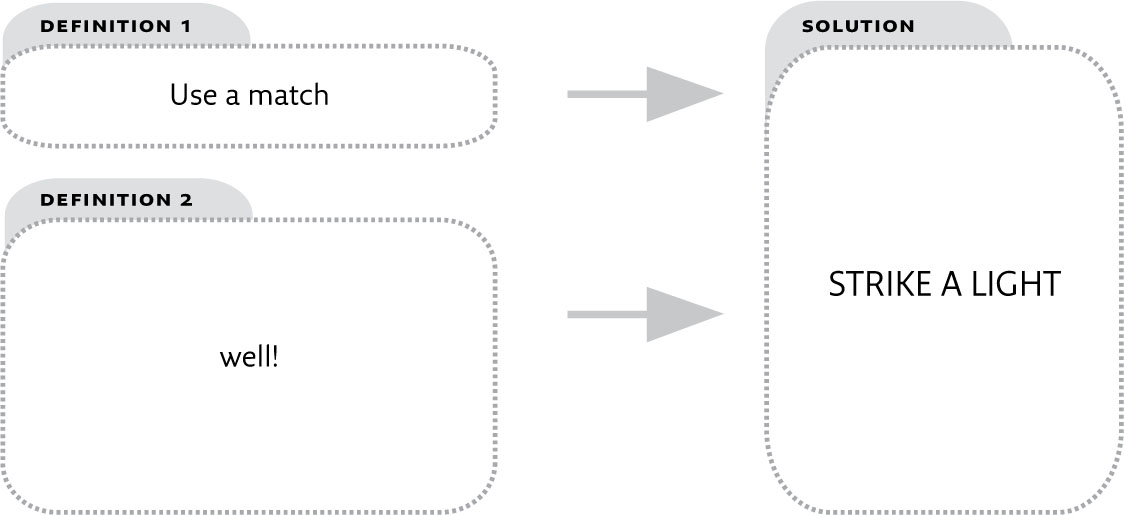

• Exclamation mark: as an indication either that something most unusual is going on within the clue, or that the clue has a remarkable or humorous feature that the setter wants you especially to notice, albeit not in a self-congratulatory manner.

Occasionally, punctuation is included to make the deciphering of the wordplay clearer, as in the next clue in which the exclamation mark helps to identify or confirm the answer.

DOUBLE DEFINITION CLUE: Use a match well! (6,1,5)

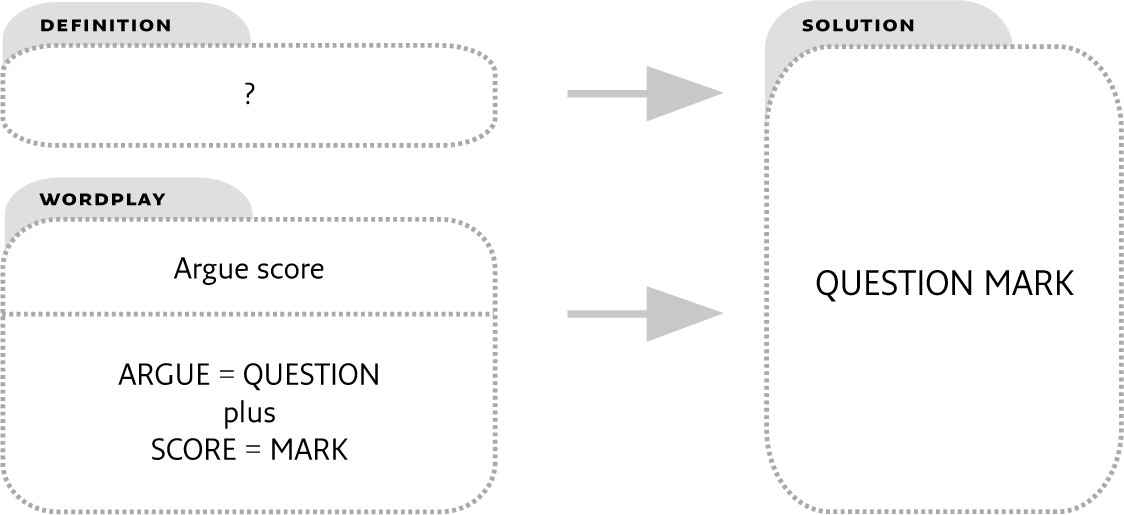

Finally, here is an example of punctuation not only being helpful but forming the definition:

ADDITIVE CLUE: Argue score? (8,4)

I would not be surprised if you are somewhat discombobulated by the points in the above section. They are undoubtedly tricky but I’m sure you will eventually find punctuation no major problem.

5. More deceptive linkwords

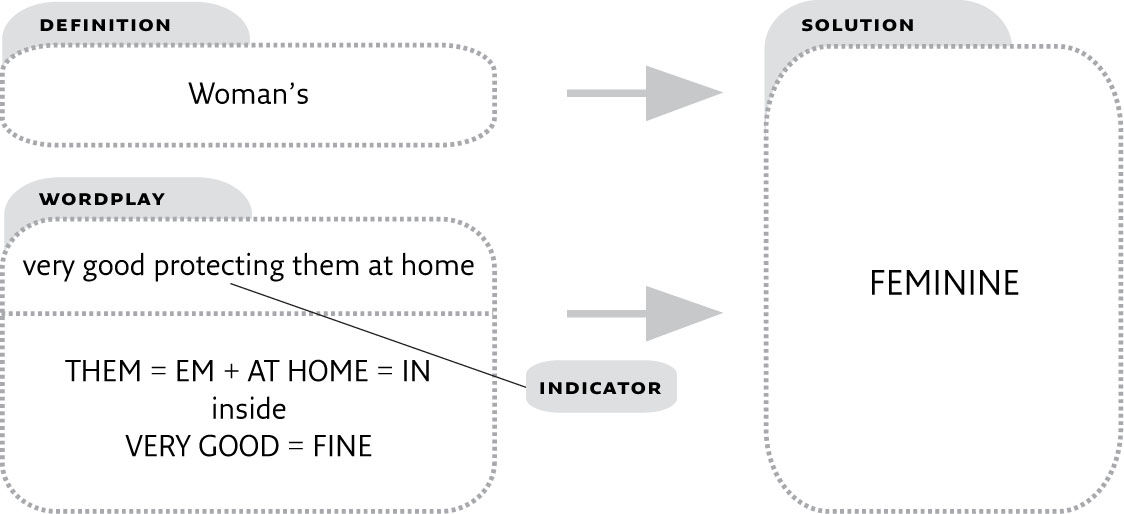

In section 2 of this chapter we saw one deceptive use of the ’s. The clue below shows another. The apostrophe looks at first glance as though it may be a linkword (for is) but in fact it’s an adjectival synonym for the solution.

SANDWICH CLUE: Woman’s very good protecting them at home (8)

6. Crossword war horses

There are inevitably some crossword terms that occur time and again, often words of two, three or four letters. It is impossible to list all of them here but those in this P. G. Wodehouse quotation (from Meet Mr Mulliner) may still be seen today:

‘George spent his evenings doing the crossword puzzle. By the time he was thirty he knew more about Eli, the prophet, Ra the Sun God and the bird Emu than anybody else in the country except the vicar’s daughter who had also taken up the solving of crossword puzzles and was the first girl in Worcestershire to find out the meaning of stearine and crepuscular.’

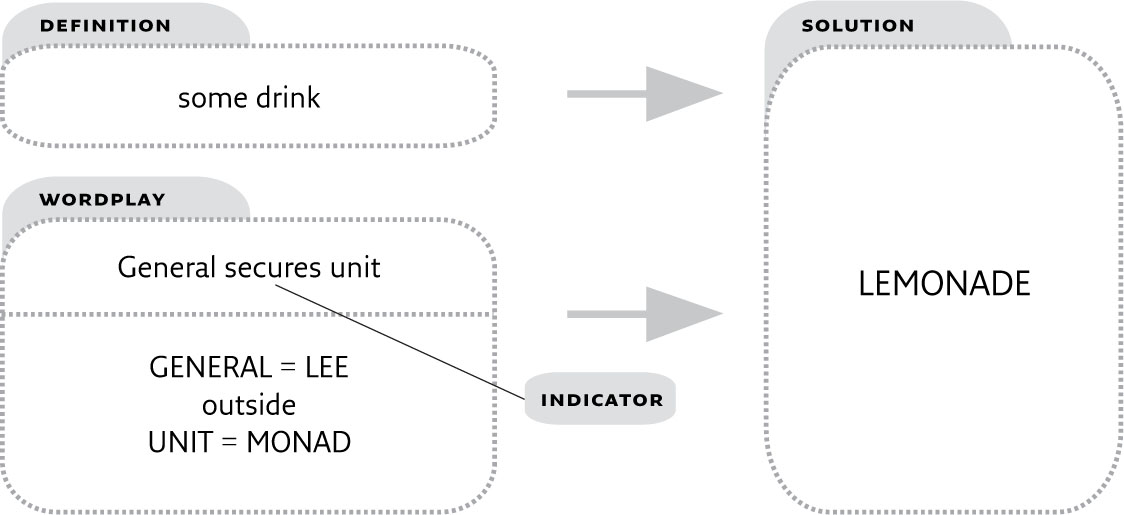

A military war horse is an American Civil War General still honoured in crosswords, as in this next clue:

SANDWICH CLUE: General secures unit some drink (8)

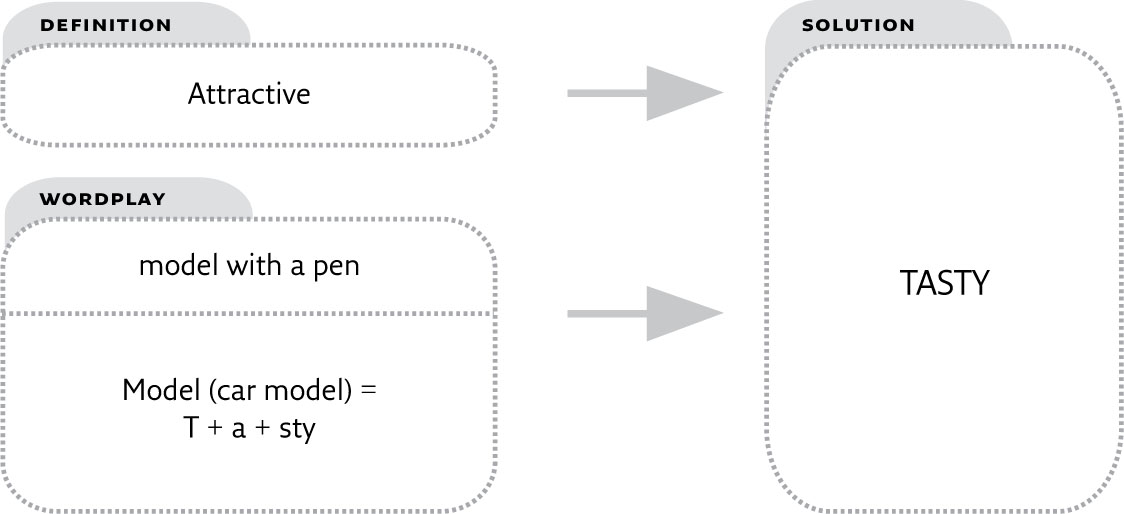

A car last produced in 1927 remains a favourite reference:

ADDITIVE CLUE: Attractive model with a pen (5)

I also note that all journalists can be ranked as Ed; that the only races known to some setters are motorcycle races TT and that the old-fashioned STEAMSHIP still sails as SS, notably in popular sandwich clues as “on board” ie with S first and last.

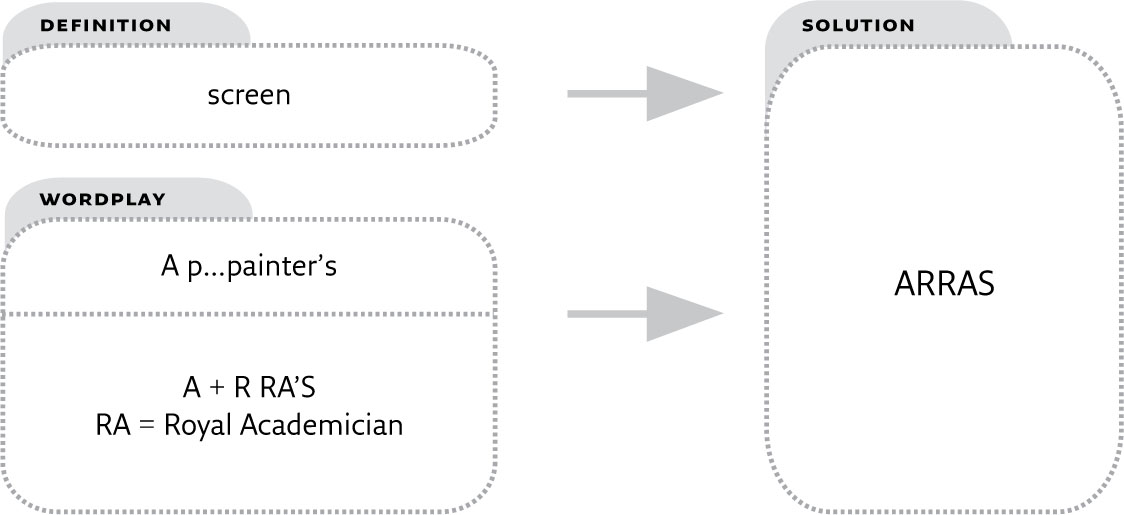

7. Stuttering clues

A sentence uttered stutteringly is indicated by repetition, as follows:

ADDITIVE CLUE: A p…painter’s screen (5)

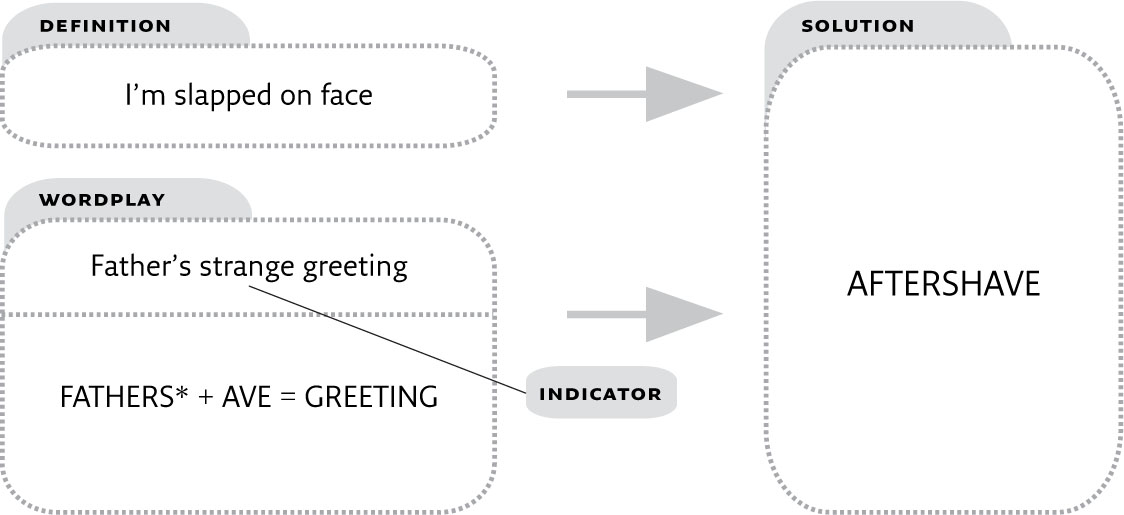

8. Use of first person singular

An inanimate object can be defined as if it were a person. This amusing clue is an example:

ANAGRAM AND ADDITIVE CLUE: Father’s strange greeting – I’m slapped on face (10)

9. Living people

Some newspapers are cautious with regard to clues referring to or defining people still alive. They are happy with this beauty about former VIPs:

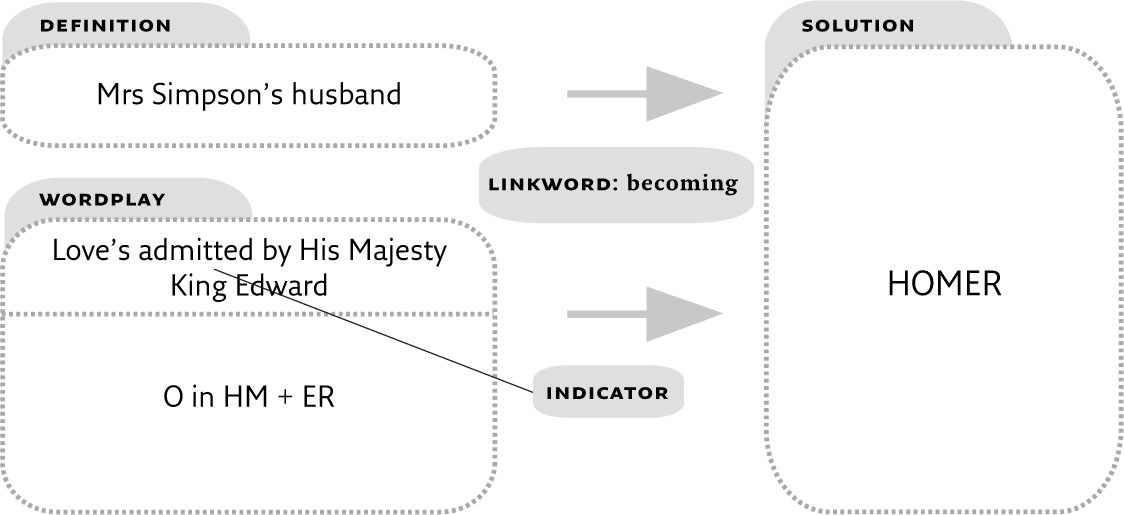

SANDWICH CLUE: Love’s admitted by His Majesty King Edward, becoming Mrs Simpson’s husband (5)

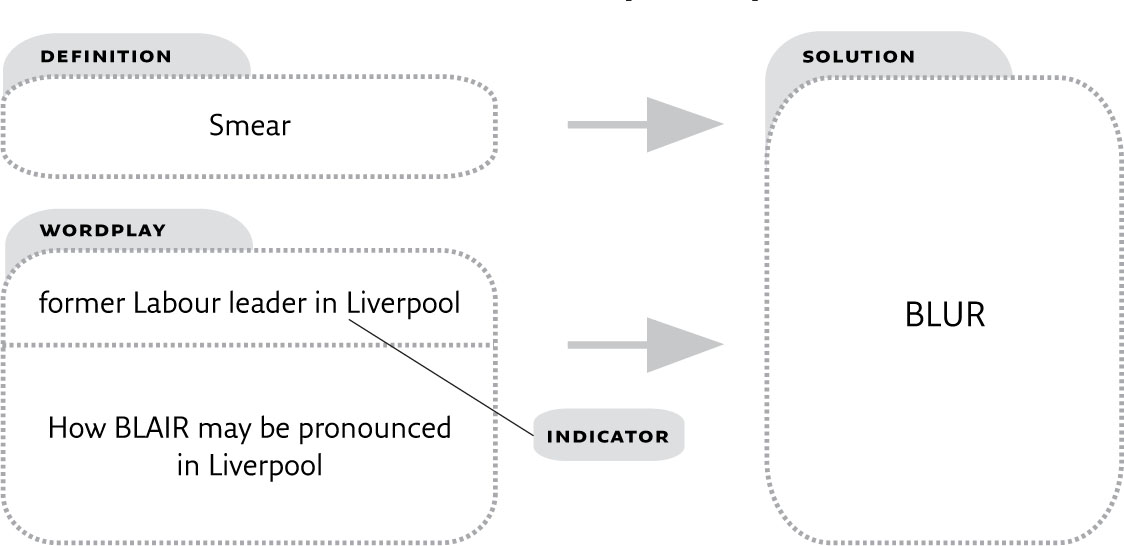

The practice though, notably in the Guardian, the Independent and Private Eye, is to revel in clues such as this one about a living person:

HOMOPHONE CLUE: Smear former Labour leader in Liverpool? (4)

10. Misleading positioning of indicators

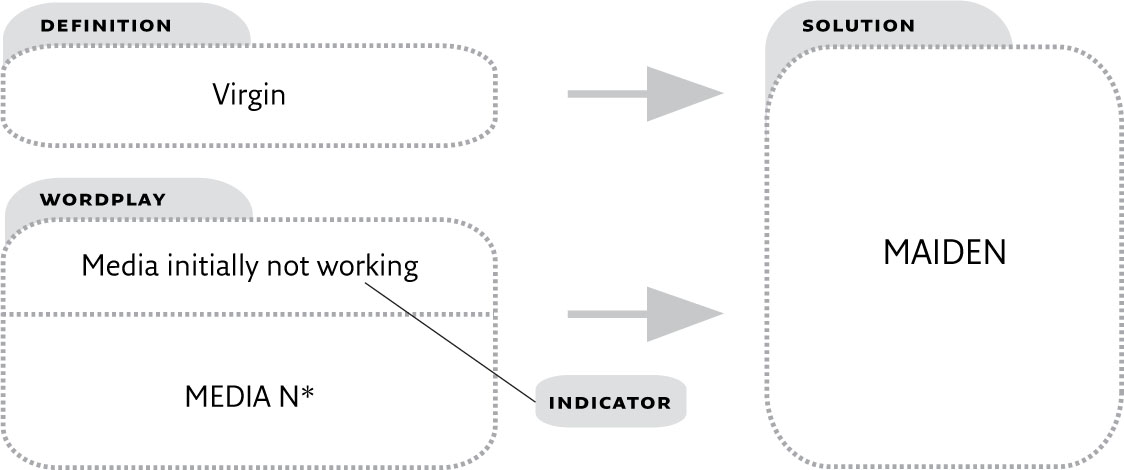

The letter selection indicator is sometimes not ideally positioned, as with initially below. Solvers have to try both M and N as letters in anagram fodder.

ANAGRAM CLUE: Virgin Media initially not working (6)

In the following improved version of this clue, ambiguity is avoided as the letter N is clearly indicated:

ANAGRAM CLUE: Virgin Media not initially working (6)