You were the most precocious and intelligent child that I

ever encountered. —WILLIAM FRANKLIN BOOTHE

Nine days after getting back from Europe, the pubescent Clare Boothe resumed her Broadway career. This time, she understudied Joyce Fair (another Pickford look-alike) in The Dummy, a four-act “crook comedy” based on Harvey J. O’Higgins’s detective stories. Her former costar, Ernest Truex, played the lead. By pretending to be deaf, dumb, and dimwitted, he rescued Miss Fair from four kidnappers and won a large reward.1

Alexander Woollcott of The New York Times found the play “rather ambling” but “lighted by a shrewd and pleasant humor.”2 Clare substituted just once for the abducted girl, but this was enough for “Joyce Fair” to be later attributed to her as a stage name.

During the successful run of The Dummy, a drama incalculably more momentous unfolded in Europe. On June 28, at Sarajevo, the assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand set in motion the war that would reconfigure world maps. As hostilities spread, and debate about the United States’ alignment intensified, the phrase “German-American” took on ominous undertones. Clare sensed ever more keenly Ann Snyder’s desire to transcend her Bavarian roots.

The guns of August were remote from childhood consciousness as Clare and David set off for a dairy-farm vacation in Bulleville, New York. Independent of their emotionally demanding parent a hundred miles away, the children learned about rural working life by participating in it. The elderly farmer paid them fifteen cents a quart for picked berries and two cents a pair for frogs’ legs, which his wife would prepare for supper “French style.” In the early morning they drove cows to pasture, and they herded them back in the evening. They filled urns for loading onto a milk train that ran through the property, churned butter, collected eggs, and fed chickens. David wrung hens’ necks, and Clare stoically plucked their feathers and cleaned out gullets. She also groomed dogs, tended an aviary, maintained an aquarium, and studied a book on how to raise guppies, only to discover that she was “not reading as fast as they were breeding.”3

David, already a mature-looking adolescent, learned more directly about the facts of life when he lost his virginity to a young local schoolteacher. In keeping with his usual practice, he told Clare about it. She was more upset than shocked. That her brother now loftily regarded himself as a man, while still treating her as a child, created a resentment greater than when he had taunted her about being unable to follow him into the military.4

Her own sexual experiences so far, apart from the probably suppressed rooftop incident, were limited to having her bottom pinched on a narrow staircase, romping in a hayfield with a country boy who clutched at her underwear, and being kissed in a hammock. But she was no slower than David in developing physically. Shortly after turning twelve, she began to menstruate.5

In later life Clare denied wanting to be an actress of any kind. It was her mother who encouraged her to persist, she said, by arranging a screen test at the Oliver Place Studio in the Bronx early in 1915. Viola Dana (future star of Naughty Nanette and Kosher Kitty Kelley) joined Clare in the audition. They were asked to express anxiety, fear, and horror. As the cameras rolled, Miss Dana emoted on cue. Her arms held off imagined threat, her lips quivered, and her eyes widened, cascading tears. Clare, awed by such histrionics, forgot to act herself.6

In spite of this inauspicious start, she secured a small role in Thomas Alva Edison’s single-reel, thirty-three-millimeter picture The Heart of a Waif. The lead went to ten-year-old Edith Peters, who, seventy years later, recalled the studio as a cavernous room with four or five sets illuminated by blue-white lights. She and Clare were not allowed to wear rouge or red lipstick because it would “look black” on screen. Between takes, they made rubber-band balls and played with the screenplay’s homeless kitten.7

Clare (second from left) in The Heart of a Waif, 1915 (Illustration 4.1)

Long before the advent of movie sound, Clare found she was expected to speak lines anyway. Charles Seay, the director, told her to act as if the camera contained a recording cylinder. She was cast as “the Little Girl on the Fence” and required to befriend an orphan child laborer (played by Edith), who thwarted a burglary and won a privileged education. The picture lasted only twelve minutes, and Clare’s edited performance amounted to just thirty seconds. In three short scenes, she sat behind Edith in church, visited the heroine at home, and at the end rode off giggling with her in a buggy.8

The Heart of a Waif was released on April 24, 1915. Preserved in pristine condition by the Museum of Modern Art, it shows Clare, almost as tall as some of the adult players, acting self-consciously in bonnet and blonde ringlets, unable to resist an amateurish glance into the lens.

Except for one other brief screen appearance as a stand-in rider eight years afterwards, this was the beginning and end of Clare’s movie career. But Waif did fan her ambition to write for the stage and screen. Even at that early age, she felt she had “the capacity to create.”9

The sometime actress spent a short vacation with Dorothy Frowert in a boardinghouse on Block Island. When Clare returned to New York City, her mother had a new male friend, richer than Messrs. Frowert and Higinbotham put together, and he was to change their lives.10

Joel Jacobs had always been a bachelor, as far as anyone knew. He lived alone in the Hotel Wellington at Seventh Avenue and Fifty-sixth Street, and worked a block away as treasurer of the Keystone Tire & Rubber Company. Forty-eight years old and of German-Jewish descent, he had slicked-down hair, a prominent nose, small, dark eyes, broad, plump cheeks, and, in Clare’s phrase, “the shoulders of a man whose ancestors had known the ghetto.”11 With his high, stiff collar, waistcoat, gold chain, and elegant walking stick, he looked every inch a tycoon.

Mr. Jacobs had a vast repertory of Jewish morality tales, which at first entertained Ann’s children. But he told the same ones too often, and they began to detect a note of cruelty in them. He liked to tell, for example, of a man who stood his young son on a high brownstone step and asked if he trusted Poppa. The boy said he did. “Then jump, and I’ll catch you.” As the boy leapt, his father stepped aside, letting him smash his face on the pavement. “I taught you never to trust nobody,” scolded the man. “Now you’ve learned the lesson, you won’t be no schlemiel.”12

David listened to such homilies with lowered eyelids and a tight smile, causing Mr. Jacobs to turn pink and angrily jingle the coins in his pockets. Clare did not share her brother’s general distaste for Ann’s beaux, but she did find this one’s accent and religion “strange.” Ann reassured her of Joel’s good intentions, saying repeatedly that he was “an original.” From this the children coined the nickname “Riggie.”13

His kindness was certainly apparent in gifts of cash, furniture, and jewelry lavished upon the whole family. He took Ann to the races and paid her bets, bought her a player piano that tinkled out “Many a Heart Is Broken,” and enhanced her beautiful neck and wrists with gold and diamond necklaces and bracelets. “He liked to feel he owned everybody,” said Clare. Soon Mr. Jacobs became indispensable.14

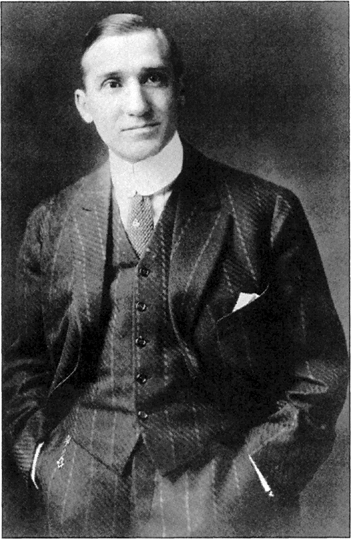

Joel Jacobs, c. 1915 (Illustration 4.2)

Not content with monopolizing them in town, he financed the summer rental of “Kidlodge,” a three-bedroom shingle cottage near Sound Beach (now Old Greenwich), Connecticut. There the Boothes—rapidly adjusting to a life of new bourgeois comforts—would spend four months a year for the next several seasons.

Joel Jacobs had his own room and drove out weekends in a big automobile. He would take them to baseball games in Bridgeport, to dinners at the Pickwick Inn in Greenwich, and on excursions into the countryside. The ensemble began to look more and more like a family. Clare asked her mother why she and Riggie did not marry, and Ann replied without hesitation, “I don’t want my children to have a Jewish father.”15

Whether or not anti-Semitism had impinged on Clare before, she certainly became aware of its subtleties now. A childless Ann Snyder might well have married Joel Jacobs. The two of them had much in common, from mutual distrust of outsiders to a shared belief that wealth compensated for lack of education. Ann’s unwillingness to take Jacobs’s name was a scruple not uncommon at the time. If David and Clare were to succeed in WASP society, she believed, they should not be hampered by Jewish ties.16

This did not, however, prevent her accepting increasing levels of aid from Jacobs, to the point that Clare began to refer to him as “my guardian.” Whether Ann ever legally made her children his wards is unknown. But he assumed financial responsibility for them. Only on rare occasions would he mock Ann’s social pretensions, sarcastically addressing her as Lady. Clare, whom he adored, was his “Angel.”17

She liked him well enough. But her deepest affection was for Ann, who celebrated her thirty-third birthday at Kidlodge on August 29, 1915. One of Clare’s earliest surviving letters acknowledges the event in exaggerated prose.

Wen I grow up—and win for myself a name in the world … I shall lead you into a grand home and say—“This, my mother, is yours!” Dearest—I promise you I shall do that … And mother, if some times I am petulant, cross and selfish—I am sorry my Boothe temprement [sic] runs away with me … but it is the ‘me’ I am going to overcome … I love you. It is a real love that one cannot talk of lightly …

Ever Your Baby Girl.18

That fall, Ann moved to new winter quarters in the Belleclaire Hotel, at West Seventy-seventh Street and Broadway. David went upriver to the New York Military Academy at Cornwall-on-Hudson, where he had transferred the year before, while Clare, aged twelve and a half, prepared for her first venture into independence. On September 22, she started as a boarding pupil at the Cathedral School of St. Mary, twenty-two miles from Manhattan in Garden City, Long Island.

St. Mary’s was considered one of the best girls’ schools in the country. The faculty, largely made up of Radcliffe, Columbia, and Smith graduates, offered a formidable curriculum in such subjects as physics, mathematics, Latin, and Greek. Clare understood that if she stayed there for five years, she had an excellent chance to enter college, because the school enjoyed a reputation for placing large numbers of undergraduates.

Autumn leaves had begun to turn when she arrived, weeping with apprehension, beneath St. Mary’s turreted, ivy-clad walls. “Don’t be a baby,” her mother snapped, escorting her in. At the registration desk, Ann effortlessly played the “Baroness,” flashing smiles in all directions. She had lied to get Clare accepted by this Episcopal bastion, claiming that her daughter was the grandchild of a bishop.19

Clare felt sick after Ann left. The two of them had become preternaturally close, as soul mates and co-conspirators. Parting from Ann was tantamount to losing a limb. After so many years spent with grown-ups, the communal juvenile world of boarding school loomed before her like imprisonment. But she did well enough in her first test for the headmistress, Miss Miriam Bytel, to place her one year ahead of her age-group, in the eighth grade. She was too chic for her class teacher, who found and removed an Erté illustration of a peacock from the lid of the newcomer’s desk.20

Even though all St. Mary’s students wore middy blouses, tunics, and saddle shoes, Clare was afraid the girls would find out that she was poorer than most of them. She hesitated to make friends, but did not try to hide her superior intelligence. In no time she found herself thoroughly disliked.

Her feelings of being relegated to “a dungeon” were intensified by her quarters, a cubicle carved out of a former chapel. She found it a confining and desolate niche. Cherubs were painted on the walls, and two images of kneeling angels flanked her bed. One window looked east across playing fields. The other faced west, towards the Cathedral of the Incarnation, where she was obliged to worship twice every Sunday, and where she would be confirmed at the end of her first year.21

St. Mary’s school days were structured, from rising bell at 7:00 A.M. to “lights out” at 9:30 P.M. There were six forty-minute lessons before lunch, and games every afternoon: hockey and basketball until Christmas, gymnastics and dancing after the New Year, track and field and tennis in spring. From five to six o’clock was “study hall.” The girls then changed into wool or silk dresses for dinner. French and German were spoken exclusively at two tables, and it was compulsory to attend them by rotation. The atmosphere in the dining room was so proper that when one girl retrieved some fallen flatware, Miss Bytel glared. “The fault,” she intoned, “was not dropping of the fork. The fault was in picking it up.”22

After dinner came two hours of “homework,” much of which Clare spent drawing “beautiful girls and ladies” around her notebook margins. Seventy years later, the Honorable Clare Boothe Luce would similarly doodle on documents at stuffy Washington political meetings.23

Her obvious self-centeredness, plus a lack of girlish frivolity, made Clare an object of increasing scorn. Hurt and lonely, she took refuge one day in the branches of an apple tree on campus. Surprisingly, another girl, dark as she was fair, was also hiding there. Her name was Elisabeth, or “Buff,” Cobb, daughter of Irvin S. Cobb, the celebrated humorist.24

Buff said that she was homesick, and the two formed an immediate bond, discovering that they both wanted to be writers. To her delighted amazement, Clare found herself meeting Richard Harding Davis and P. G. Wodehouse on a visit to Buff’s house. But it was their host who became her first major literary influence. Mr. Cobb was a formidable-looking Kentuckian with a broad, big-lipped face and a 240-pound girth. Cheerfully eccentric, he worked in a study decorated with Indian artifacts, wearing a conch-belted smock and kneesocks. At dinner he betrayed a huge appetite for pickles, relishes, and pigs’ knuckles, and expressed himself, between bites, almost entirely in stories and jokes. Despite his gross appearance and avoidance of serious topics of conversation, Clare came to appreciate Cobb’s acute intelligence and professionalism.25

Clare and “Buff” Cobb at St. Mary’s, c. 1916 (Illustration 4.3)

She liked the Cobbs, and they liked her. Buff’s mother described Clare as “the most startlingly poised child I ever knew.”26 Visiting often, Clare luxuriated in the kind of close, compatible family warmth she had never had at home, and she was bereft when Buff, ill with bronchitis, did not return to school in the fall of 1916.

Lonelier than ever in her second year, Clare devoured whole sets of Dickens, Thackeray, and Kipling, as well as modern novels. She especially identified with the solitary, clubfooted schoolboy in Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage.27

“What rage for fame,” Clare wrote in St. Mary’s yearbook, “attends both great and small.”28 Her determination to be eminent did not go unnoticed. Fellow students designated her the most conceited girl in the school. Convinced that she would never be either successful or popular there, she prevailed on her mother to take her away. When she departed Garden City Cathedral precincts in the spring of 1917, America was at war with Germany, and her life was about to take another important turn.