Je vis en espoir (I live in hope).

—CLARE BOOTHE’S PERSONAL MOTTO AT CASTLE SCHOOL

Ann Snyder was ambivalent about her fourteen-year-old daughter’s avid intellectualism. On the one hand, she encouraged her book consumption. On the other, she had compromised Clare’s chances of a university education by removing her prematurely from St. Mary’s. Her suspicion that advanced study might make the girl an irredeemable “bluestocking” was compounded by fear of keeping her out of the marriage market for several crucial years.1 Since Ann’s chief aim was to find Clare an eligible husband sooner rather than later, she opted for some final polish at a school where parlor arts and graces, and live foreign languages, were considered more desirable accomplishments for an attractive girl than dead languages and college degrees.

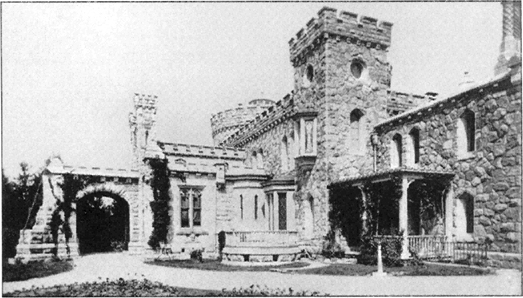

The institution Ann chose was the Castle School, a fortresslike granite pile perched on a hill above Tarrytown-on-Hudson. Its prospectus advertised it as “a civic West Point for girls,” turning out young women “with broad not petty minds, with refined not tawdry tastes, with direct not shifting speech, with strong not nervous bodies”—sensible antidotes to the neurasthenic leanings of the age.2

The Castle, Tarrytown-on-Hudson, New York (Illustration 5.1)

Clare arrived there on September 26, 1917, as a tenth-grade sophomore. She loved the Castle on sight. At her feet stretched “the peaceful Hudson with its hazy border of blue hills, and the tiny village bathed in the warm autumn sunlight.” Lacrosse fields, forested walks, and mansarded student residences spread out across spacious grounds. Inside the crenellated main building was a circular drawing room with columns and vaulted ceilings, massive portraits, and a golden harp. At night, after the sun set over the Jersey shore, girls could stand on a broad porch and watch the steady flashings of a distant lighthouse.3

Cassity Mason, the Castle’s founder and principal, was considered a radical in finishing-school circles. She propelled her students towards professions usually reserved for males. All they needed was self-confidence. “Just ask God, and She will help you.” In appearance the headmistress belied her scientific leanings. She was stout, motherly-looking, and monochromatic, with pale-gray, moist eyes and upswept gray hair. In iron gray poplin she was a model of efficiency during the day, while in iron gray satin she appeared a softer presence at the nightly dinner table.4

Most of Clare’s 111 fellow students came from middle-income families and had already completed high school courses elsewhere. She was assigned quarters with Ruth Balsam, an impressionable Southerner. Their study-bedroom consisted of closely placed cots, two desks with wicker chairs, a dressing table, corner table, geometric carpet, and small chandelier.

Clare, fast approaching her adult height of five feet five, was fashionably plump at 155 pounds (though 30 pounds above her own ideal). To Ruth, she looked like a fairy-tale princess, her hair “golden and soft with polished highlights in the waves,” her complexion flawless. It was rumored that Mrs. Boothe bathed her daughter in milk.5

Over the next two years, Clare would blossom in mind as well as body, skipping eleventh grade and becoming a senior at age fifteen. The Castle’s curriculum placed less emphasis on academic achievement than St. Mary’s. Nevertheless, within seven months, Clare achieved an 88 percent average, with 96 for English history, 93 for ethics and sociology, 99 for costume design, and an astonishing 100 for physical training. Her average would soar to 94 by October of 1918. Before she left, her proliferating talents would cause one teacher to recommend that she go on to the Art Students League of New York, and another to prophesy a career in public speaking or journalism. Clare herself was convinced that one day she might produce “the Great American Novel.”6

Alternatively, after seeing Ethel Barrymore in Déclassé, she wrote in her diary, “I’m not flattering myself—but I think with half a chance and some experience I could be every bit as good an actress.” She even developed a belated interest in music, and reacted swooningly to a recital by Sergey Rachmaninoff. “My heart aches and aches to play the piano. Or yes the violin. Oh, God my father is rising within me.”7

Her facility in so many fields bewildered her. “For Mother’s sake I must make a name for myself … What am I supposed to be?”8

One of Clare’s schoolfriends recalled, “She was always driving herself through some inner compulsion to find out the way of everything. When the rest of us were reading Elinor Glyn, she would be deep in Racine … and while she soaked in the tub she’d have Plato propped on the taps in front of her. But she was no goody-goody. If anybody annoyed her, she had a tongue like a black snake whip.”9

Clare struggled to curb her natural acidity, with mixed results. Having alienated St. Mary’s girls by her standoffishness, she took pains to be public-spirited at the Castle. She labored through the night at extracurricular tasks till dark circles appeared beneath her eyes.10 At different times she was vice president of her class, art editor and business manager of The Drawbridge magazine, and chairman of the Current Topics Club.

Other girls were struck by her perfect grooming, vivacity, and enthusiasm. They had no doubt that one day she “would do great things.” She always took the honors in weekly speeches on news events. Her poetry was often overwrought and poorly scanned, but they admired it anyway—as they did her prowess on the hockey field. By her own assessment her mind was too quick for her feet in ball games. She preferred, she said, “to sit under a tree … with a volume of Rostand or Paillerou.”11

Maturity was some way off, and in the interim Clare could not conceal all her besetting faults. The bruising judgment of St. Mary’s was resurrected when a friend called her “conceited.” What Clare longed for most was to be adored. “Wonder what it is about me that no one loves me better than anyone else … I’m ‘popular’—yes,” she confided in her diary, “but I’d rather ‘have one person love me paramountly’ [sic].”12

It did not occur to her that her peers might want some affection in return. Indeed, she found it hard to love anyone other than Ann and David. “My whole heart and soul is wrapt up in three things,” she wrote, “Mother, Brother and my ambition for success.”13

Yet she lacked neither affection nor accolades at the Castle. The Drawbridge’s final ratings awarded her first place for Most Artistic, Cleverest, and Prettiest, as well as second place for Most Ambitious. “In my heart of hearts,” she admitted, “I know I only deserve one—the last.”14

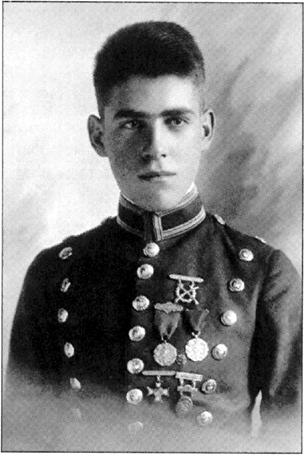

Clare scored high marks in dancing and deportment (100 percent in the latter) and welcomed the attentions of handsome cadets at Saturday-night balls at the nearby military academy. One purposeful youth gripped her so tightly as they fox-trotted to “Saxophone Sobs” and “Dark Town Strutters” that she bore the imprint of his uniform buttons on her dress the rest of the evening.15

David Boothe at the New York Military Academy, c. 1917 (Illustration 5.2)

Her first substantial affaire de coeur was with an Air Corps lieutenant, Lloyd D. Miller. He held her hand at the movies—“the greatest thrill”—and wrote passionate letters. But then he was posted abroad, and the correspondence ceased. Clare romantically assumed that he was “dead and buried on the fields of Flanders.” Her interest in him abated somewhat when she found he was not.16

Meanwhile, her appetite for other flirtations continued. Ralph Ingersoll (a future publisher of Time) recalled Clare at this period as being “a party girl … blonde, good figure … would neck, but look out.”17

The type of man who attracted her sexually resembled William S. Hart, the angular, unsmiling hero of countless silent westerns. “Pretty” features, like those of Rudolph Valentino, repelled her. When it came to imagining her ideal husband, she thought not of looks but of practicality. He must be a businessman earning a substantial salary, because love could not blossom “among greasy pans, soiled linen and smarting soapsuds.” Moreover, he should have “a splendid code of honor” and worship her “better than God.”18

Her “dream” man tended to be sensitive looking and unreachable, like the English poet John Drinkwater, on whose photographic portrait she yearningly wrote, “Yours—John.” Someday, perhaps, an aristocratic figure like him would enfold her in his manly arms …

Her personal bookplate represented a knight on a white charger. Looking at it in old age, she sighed, “He never came.”19

Ann Clare Boothe, c. 1918 (Illustration 5.3)

Joel Jacobs provided plenty of pocket money to satisfy Clare’s burgeoning needs. On just one day trip to New York, she spent more than twice as much as her mother used to earn at Tecla’s in a week. Jacobs paid for her train tickets, taxis, riding lessons, lunches, corsets, combs, and ice creams. He also financed her insatiable entertainment habit. In a year and a half, she recorded seeing approximately sixty plays, movies, musicals, operas, reviews, or vaudeville shows—more than three outings a month. Riggie further indulged her with large baskets of fruit, flowers, and candy dispatched to the Castle, a leather-bound set of the novels of Alexandre Dumas, and sixteen ten-dollar gold pieces for her sixteenth birthday. From time to time he would award her shares in his prospering tire company. On Sundays he often drove out to Tarrytown and treated her to lunch—“Baked Alaska—yum!” Missing his “Angel” in midweek, he would send a chauffeur to collect her for dinners at the Waldorf-Astoria. He jokingly called the great hotel “a joint,” but to Clare it was “Life! Life!”20

The more lavishly Jacobs spent, the more she enjoyed his company. “Riggie is a wonderful man, and I just adore him,” she wrote in her diary. “Jew! Yes. But any white Christian who was ½ as fine as he would be considered a miracle. Riggie thinks very wonderful things of me … I shall do my best to make him really proud.”21

Ann Snyder might have wondered whether Jacobs was becoming more interested in her daughter than in herself. He was furious when the teenager stayed out late with friends at a cheap nightclub, and glowered when other men stared at her, as they invariably did now. Clare suspected, with satisfaction, that his jealousy was a little more than paternal.22

Clare’s first foray into foreign policy, which was to be the passion of her later years, took place on August 23, 1918, in Sound Beach. Patriotic fervor aroused by the war had spurred her to raise money for the Red Cross by producing and stage-managing a children’s performance of Cinderella at the town school, for a total profit of seventy-five dollars.

She had no part in the play herself but, clad in a rose-colored gown, made a poised opening speech. “We must have the League of Nations to keep the peace, and America must stay in it … Russia must emerge from the war whole and sound. If anything happens to Russia there is sure to be another war.”

Next morning a local newspaper reported, “Sound Beach is strong for Miss Boothe today.”23

On Thursday, November 7, booming West Point guns and downriver sirens signaled—four days prematurely—that Germany had surrendered. Clare and her fellow students, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the Marseillaise, and “God Save the King,” climbed a tower to hoist the American flag. After dark Miss Mason hired four cars to take a group of seniors to New York. Clare caught sight of her mother and Riggie in the traffic and joined them for a ride around Manhattan, through delirious, surging crowds. Caruso was singing “Over There” from a window in the Knickerbocker Hotel, and people stood ankle-deep in newspapers, listening.24

Clare gave her own postmortem on the Great War in an eight-page essay written and delivered in French to other Castle students. The title, “Ce qu’on sème on récolte” (What one sows one reaps), was apt. She argued learnedly that the recent war had its origins in the failure of Western European nations to prevent Prussia’s appropriation of the mines of Lorraine forty-eight years before. Bismarck had seized them in order to build up armaments and, in consequence, encouraged the later megalomania of the Kaiser. This was allowed to go unchecked, and so, she concluded, “1914 est la résultat de 1870.”25

Focusing more and more on literature as a career, Clare began to write with skill and psychological perceptiveness during her final months at the Castle. In a short story called “The Mephistophelean Curl” and a one-act play, “The Lily Maid,” she betrayed a jaundiced view of sexual relations, analyzing respectively the amorous manipulations of a forty-year-old woman and the moral musings of a convent girl torn between purity and profligacy.26

Her own experience of sex so far was limited to rather chaste kissing and petting. She wrote rather more convincingly of the Maid’s desire to get “boiled, stewed, spiffed and tight.” Sex education at the Castle was the province of Miss Lum, a nervous spinster who displayed diagrams of only female organs and was vague about the mechanics of intercourse. “Of course, girls,” she would say wistfully, “I have not actually had this experience, but I am told it is very beautiful.” The most valuable part of her lecture, as far as the students were concerned, was a list of “tricks” they should not practice, lest boys become overfamiliar. They carefully memorized the list for use at the next West Point ball.27

Clare graduating, May 1919 (Illustration 5.4)

Clare, cautioned by a teacher’s farewell warnings against “egoism” and “coldness,” graduated from the Castle on May 27, 1919. To the strains of Mendelssohn’s “Priests’ March,” she entered the gymnasium for the last school day, along with eighteen class members. Her white, georgette-crêpe dress hung straight from the shoulders, a fitting cover for silk and lace underwear that had been made by her mother over many weeks. She carried a bouquet of roses and sweet peas.28

“Yes, yes, she is our prodigy and our genius,” her classmates were to write in their yearbook.

Yet, just the same, she is as lovable as she is brilliant. Ann Clare is one of those girls who can do anything. In Art,—well you’ve seen our class posters. In writing,—just look through the Drawbridge. In conversation,—you all know her wit. In fact, she is just a little bit of “all right” from beginning to end. She is very ambitious for a great career, and the Senior Class all wish her the best of luck and feel sure that some day in the future we may say, “Oh, yes, Miss Ann Clare Boothe, the famous author and illustrator? Why I knew her back in 1919 at the Castle School!”29

During commencement events, the headmistress was heard to say that Clare Boothe was “a very bright girl who would some day make her mark in the world.” Miss Mason had always paid close attention to her smartest pupil, writing her encouraging notes and driving her to town for lunches and matinées. Had Clare not been so self-absorbed, she might have appreciated these special favors. On the contrary, her views of the iron-gray lady grew vitriolic as memories of the Castle faded. “A hard-hearted old cuss,” she wrote only three years later, “and very selfish and conceited which is only natural in an unmarried old woman of her age and proclivities.”30

Clare hoped for more stocks from Riggie as a graduation present. They were not forthcoming, but she was hardly disappointed to receive instead a green Essex roadster and, from Ann, a desk for her own room in a new house.