All human evil comes from … being unable to sit still in a room. —BLAISE PASCAL

If the Beaux Arts Ball, with its royalty-aping vanities, privately struck Clare as decadent, it did not stop her and George from throwing a costume supper dance five weeks later that regressed through fatuity to infantilism. On March 2, 1926, they decorated the walls of the Brokaw mansion with pictures of nursery figures and required party guests to dress as children. Those in default had ribbons clipped to their hair and bibs tucked under their chins. Teddy bears were carried and toy trumpets tooted. The hostess appeared as a French doll, with a pink bow attached to her long, golden curls, and the host sported a white blouse buttoned to little-boy pants.1

This mid-Lenten frolic marked the nadir of Clare’s career as party giver and the beginning of the end of her marriage. She would remain with George three more years and experience pleasures as well as other fatuities. But from now on she plotted how to escape her gilded prison with minimum damage and the maximum amount of money. Complieating her strategy were appeals from the two other dominant men in her life—David Boothe, embroiled in financial scandal, and her father, fading in health and almost penniless in Southern California.

At least little Ann (now twenty months old) could be taken care of by a nanny. After a strangely belated baptism of the child by the Reverend Henry Sloane Coffin on April 21, her parents sailed for a short vacation in France.2

They stayed in Paris for a few days, which George measured out in morning porto-flips at the Hôtel Meurice men’s bar. One day he nonplussed a male friend by inviting him to lunch on the Left Bank with Thelma Furness and Gloria Vanderbilt, but not Clare. The friend wondered if George, formerly so uxorious, might be contemplating an affair.3

After visiting Biarritz for a few weeks, the Brokaws recrossed the Atlantic in late June to spend the summer at Newport. A gossip columnist took note that they were the only representatives of George’s family to have broached this bastion of Old Guard society.

Clare Brokaw is certain to make a decided impression up here, for in addition to social graces, she is very clever, and writes and draws very well … She has the advantage of numbering Mrs. James Stewart Cushman among her intimates, and that lady … will see to it that George’s pretty, young wife gives the frequently fatal Newport pitfalls a wide berth … other Mrs. Brokaws are vert [sic] with envy.4

George leased “Beachmound,” the Benjamin Thaw villa overlooking Bailey’s Beach, for three months. That Mrs. William Vanderbilt II had rented the house the previous season gave it extra cachet. Clare wisely did not offend the grandes dames of Bellevue Avenue with new-rich pretensions, and her “unassuming manner and quiet dignity” (to quote Billy Benedik) were generally praised. Only one dowager expressed doubts. “Clare Brokaw is an odd girl. She has a room off her bedroom just filled with books, and she reads them.” By season’s end Clare was so sure of a permanent position in Newport that she persuaded her husband to sell their Sands Point house—at a fifty-thousand-dollar profit—after just twenty months.5

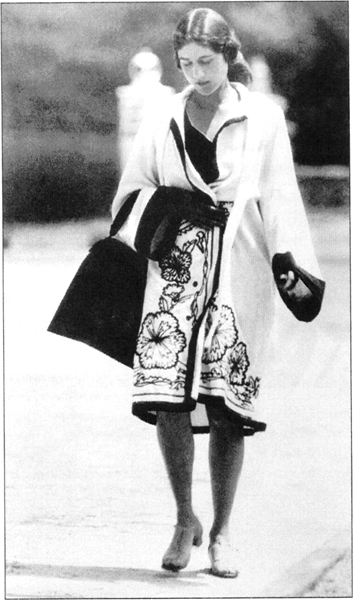

Clare Brokaw, c. 1926 (Illustration 13.1)

Back in New York in late September, Clare had noticeably gained social confidence. She was more selective in her choice of acquaintances and events, and more practiced in handling the press. The satisfying result was seeing her name circled dozens of times in articles sent by her news-clip service. Reporters at Belmont Park and Carnegie Hall noticed Clare Brokaw smiling at the right people and being conspicuously popular with “stags” at débutante parties. Blonde and exquisite in eye-catching white velvet at the Metropolitan Opera’s opening night, she earned one journalist’s accolade as the “loveliest matron in the entire ‘golden horseshoe.’ ”6

Yet social triumphs did not keep discontent at bay, and Clare enumerated her woes to Ann Austin, who was wintering in Palm Beach. A painful tear in her uterus required stitching, little Ann disturbed her when she was trying to write, it was impossible to find decent dinner guests, and George obstinately refused to cash in all his assets, despite her urging that liquidity would free them both to come and go as they pleased. Instead, he talked in maudlin fashion of dying within ten years. “I should weep now about that?” she wrote her mother.7

Actually, George’s health was fast deteriorating, exacerbated by his desperate drinking and insecurity about Clare. One day in the Colony restaurant he had a nervous attack when Max Reinhardt ogled her. He seemed afraid she might desert him for the stage. Clare tried to reassure him by joking that, at almost twenty-four, she was already too old to be a showgirl. But she did not mind telling him her real ambition: to write for the theater.8

As luck would have it, that spring Clare met a successful European playwright in Bermuda, where she and George had gone on vacation. His name was Seymour Obermer, and she was immediately drawn to his sophistication, as he was to her stock of dramatic ideas.9

They decided to collaborate on a three-act comedy called Entirely Irregular. The plot, set in a country house twenty miles from New York City, involved a wealthy businessman who, weary of his nagging wife and greedy daughter, feigns a mysterious suicide in order to run away with his secretary. The authors copyrighted the play on April 23, 1927, but it remained unproduced, perhaps because its overtones of melodrama were irreconcilable with its comic satire. One epigram, of the kind that would later characterize The Women, echoed Clare’s own marital state. “I’ve always noticed, when a woman is faithful, she takes it out on her husband in other ways.”10

While the writers worked, George drank. One night, stuttering with shyness, he tried to regale Seymour and Nesta Obermer with his notions of “the g-good, the t-true, and the b-b-b-beautiful.” Clare, rescuing him, segued into a haunting ballad she had picked up somewhere, her off-key voice wafting out from their veranda:

How beautiful they are,

The lordly ones

Who dwell in the hills,

In the hollow hills.

They have faces like flowers,

And their breath is a wind

That blows over summer meadows,

Filled with dewy clover.11

Nesta, sensing “a great ocean of loneliness” around her new friend, deduced the underlying cause. Clare had a creative spark, but the “Big Infant” she had married did not.12

“It has been many a moon since Newport has seen such a resourceful young hostess as this pretty blonde,” Town Topics enthused at the start of Clare’s second season there. As the summer activities of 1927 got under way, the local press applauded her performance as “Beauty” in a pantomime fundraiser for the League of Animals, ran pictures of little Ann in her go-cart, and featured George playing golf in the newly fashionable flannels, instead of old-style knickerbockers.13

On September 5 the Brokaws trod new cultural ground with a thé musicale for 150 people at Beachmound. Clare conceded afterwards it had been “an unsuccessful experiment” wasted on “a group of Philistines, who are living … by the sweat of their grandfathers’ brows, but who shudder at any mention of the word perspiration.”14

She continued nevertheless to migrate with the smart crowd, following them in October to the Homestead spa in Hot Springs, Virginia, for two weeks. Riding pine trails alone through the purple-hazed mountains made her feel insignificant yet inexplicably content. She wrote Vernon Blunt that she usually experienced happiness only in social surroundings, “in proportion that I feel myself important.”15

The Brokaws returned to Manhattan in time for the opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s new season, as well as for a dinner dance and slide show in honor of the transatlantic aviatrix Ruth Elder Others at the party, hosted by William Randolph Hearst, included New York’s flamboyant mayor, Jimmy Walker, Alva Belmont, Jay Gould, Elsie de Wolfe, the designer, and Cole Porter—not yet famous on Broadway but already a conspicuous talent. This gathering marked Clare’s formal entry into “café society,” Manhattan’s charmed circle of Old Guard renegades and new celebrities from the theater, movies, art world, politics, and journalism.16

She longed to feel an equal in such cosmopolitan company but often found herself embarrassed by George’s drunken behavior. “Don’t worry,” said Ann Austin, “he’ll fall down those marble stairs soon enough.” Clare admitted to the same thought, adding that she “often felt like giving him a push.”17

Her sense of entrapment intensified in December, when George lost his battle to pull down the Brokaw mansion. He had failed to marshal a family majority in favor of demolition.18 Clare saw no immediate alternative, other than complete redecoration of the fusty old house. When work began in early 1928, she, George, and little Ann moved to temporary quarters on the top floor of the Sherry-Netherland hotel, then sailed to Europe for the spring and summer.

By now Clare felt mentally and emotionally ready to leave her husband, but she was not secure enough financially. Some years before she had set up a surreptitious trust fund, purportedly for Ann Austin, with generous checks that George assumed she was spending on furs and jewelry for herself. David Boothe had grandly promised to double the fund on Wall Street, then lost it all. He had also persuaded her to borrow twenty thousand dollars from his employer, Robert C. Beal of Broad Street, concealing the fact that he had used stocks and bonds of Joel Jacobs as collateral for his own devious purposes.19

Mr. Beal soon began to complain that Clare was not paying back her loan fast enough. Reluctantly, she went to George and, without revealing the subterfuge of the “trust fund,” got enough money to settle at least part of it. Her aid failed, however, to keep David out of serious trouble. On top of his shady financial dealings, he drank, smoked, womanized, and gambled. To him playing the stock market was akin to betting on cards and horses: the higher the stakes, the greater the thrill. Clare complained that “he couldn’t hold onto a dime for more than three seconds.” Yet for unexpressed reasons going back to the shared sufferings of their childhood, she was unable to either control or disown him.20

Riggie discovered what was going on and threatened to sue. David ran off, re-enlisted in the Marines, and by early spring was in the mosquito-infested jungles of Nicaragua. He wrote Clare that he was fighting Augusto Sandino’s guerrillas and hunting down bandits smuggling Communist-supplied weapons across the Honduran border.

Sounding temporarily contrite, he added that he wanted “to do penance and give you and mother a much deserved breathing spell.” But he complained about the milkless coffee and hardtack he had to endure, in contrast to his preferred Fifth Avenue diet of oysters and baked Alaska.21

When Ann Austin wrote back reminding him that Clare had her problems too, he sent his sister a contrite letter.

I can understand what you must daily endure and suffer, and I believe that whatever course you take will be the correct one. After all, your life is your own. You’ve been working for us all long enough, and are entitled to some freedom …

Although I’ve never considered your happiness or your feelings, I would give anything just to be able to die for you. You’re the one person I’ve always looked up to and respected and to me you can never do wrong.22

Clare received these effusions in Paris, where the Brokaws had been joined by Ann Austin at the Hôtel Windsor Etoile. Though David might have meant what he penned, he was more likely trying to keep her sweet for further loans.

Weary of George’s childlike need for attention and companionship, she invited Vernon Blunt to cross the Channel one day and lunch with them at Les Ambassadeurs. It was apparent to the still-lovelorn Englishman that if there had ever been tenderness between the Brokaws none remained. His once gay and ethereal “white narcissus” was married to a shallow, dissolute, and ignorant man, as Vernon saw when the conversation turned to philosophy. George clearly “knew damn all,” and it burnt out Vernon’s soul to think he had once imagined himself not good enough for Clare. On the contrary, she was the one with debased values, mired now “in the throes of mundane compromise.”23

After Ann Austin went home in June, Clare wrote her a series of dispirited letters. George was staying “comparatively sober,” but he had no pride and was “certainly going crazy.” She wondered why she had not taken to drink or become “a babbling idiot.” Ann’s hope that he wouldn’t “last long” was futile, because he had amazing reserves of strength. Next winter, after two or three months on East Seventy-ninth Street, she intended to leave him. “I can’t stand it any longer.”

She asked Ann to investigate Connecticut divorce laws, because hearings in New York would be devastating to George. In any case, adultery was the only ground for divorce there, and Clare was sure that her husband, whatever his other failings, had never been unfaithful.24

While determined to separate, she did not intend to leave Paris empty-handed. In addition to acquiring quantities of clothes and jewelry, she tried to order some furniture by the Deco master Rhulmann. But he was too backlogged, and she had to make do with traditional French pieces, buying enough for all the ground-floor rooms of the Brokaw mansion.25

In the third week of July, the family went south to Aix-les-Bains, and checked into the Hôtel Splendide-Royale et Excelsior, situated on a lake between two Alpine ridges. George, complaining of more or less permanent tingling in his arms and legs, was warned by a doctor that he risked paralysis or lunacy if he did not immediately abstain from alcohol. Clare naively hoped he would build up his strength by drinking milk, because, she wrote Ann Austin, “he’s going to get a surprise from me one of these days.” Little Ann was no solace to George. At four years old, she refused to embrace or even talk to him. Her only diversions in the hot, dull valley were boating and swimming with her adored mother.26

They all went north on August 6 for three weeks at Le Touquet. The sea air had its usual effect on George. One night he lasciviously lunged at his wife, and she pushed him away with such vigor that he fell and cut his head on a radiator—badly enough to require stitches. This behavior was more the result of alcohol than youthful libido. At forty-nine, George showed signs of having aged “terribly”—not enough, apparently, to satisfy Clare. He was by no means in “dying condition,” she told her mother, “and I am not going to waste my life waiting for him to get in it.”27

The Brokaws returned unrefreshed on the Ile de France in early September and moved into their newly decorated house. A few weeks later, George decided to resume his convalescence at White Sulphur Springs. Predictably, by the time Clare joined him in early October, he was drinking again. His whole personality was, as she put it to Ann, “so curled up inside of mine” that he was as dependent on her as “an unborn baby.” Worse still, he was now beginning to suffer from delirium tremens.28

Back in New York, she took drastic action, hiring an authoritative doctor who confined George to his room. The patient was forbidden liquor and all contact with the outside world, including his wife and daughter. Telephone calls and letters were the only means of communication allowed. In a series of pathetic pencil notes to Clare, George tried to enlist her aid in denying his alcohol problem. “I am taking the rest you advise … When you see people please say that I had congestion of the lungs or something like that.”29

On another occasion he wrote, “There is really nothing the matter with me … my spirits sink to a low ebb when I cannot even … say one word to Sweetie Pie … Wish you felt like that towards me.” He begged for freedom to attend to some “most important stock transactions” and pined for his “library,” where Clare had once found gin slopping around in his silver golf cups.30 The only thing that cheered George during his incarceration was the election of Herbert Hoover to the presidency on November 6.

Clare made formal plans for a Reno divorce. Simultaneously, she was forced to confront another vexing personal problem.

William Franklin Boothe was now abjectly living in a leaky beach cabin just south of Santa Monica. Versa Boothe, the third of his wives—or fourth, if Ann could be counted in common law—had turned against him. He needed five hundred dollars to divorce her and hoped that Ann Austin might provide it. All he wanted from Clare, so far, was the return of a ring he had once given her, presumably so he could pawn or sell it.31

Ann’s dread was that he might reveal his existence to the still-unsuspecting Dr. Austin and George Brokaw. She had written back warning him not to disturb their daughter’s “place.” Now, just as Clare was in the throes of divorce, the sixty-six-year-old William contacted her directly.

Claire, [sic]

I am writing this from Manhattan Beach, where I have been for some time past ill. Had it not been for John and Charley [his brothers] I would in all probability have had to find friends to help me tide over, for … with sight and hearing impaired, and suffering from pernicious anemia as well, it is not so easy to help yourself.

In the four rambling pages that followed, he never specifically asked her for money, for reasons of pride (“Amour-propre is … strong in me”). He feared, however, that his family was about to ask Clare for financial help on his behalf. “Their attitude is—‘Your daughter whom we know is well to do—why does she not come to your assistance?’ ” Between the badly typed lines, he painted an affecting portrait of a wronged father, sick and down on his luck.

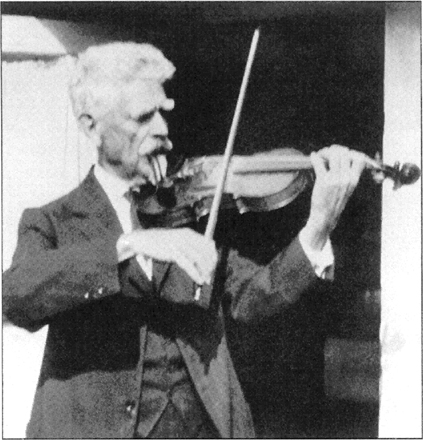

Looking back over their past years of alienation, he recalled that he had once been “one of the biggest piano manufacturers from a standpoint of volume in the world.” Somehow or other he had gone “to pieces” and become a salesman to support his family. But he had always been by nature a musician, and music had supported him comfortably until two years ago, when his health broke down. Since then, he had been working on a violin technique treatise—

A Gradus ad Parnassum that will live after I am gone. I am poor—practically destitute, but so have been many very great musicians. I can’t teach more because of my hearing—but I hope to hang on to life for a year or two longer in order that I may marshall and array all my notes, progressions, and excerpts.

Despite the querulous tone of the letter, Clare could not fail to be impressed by an enclosed Los Angeles Sunday Times profile of her father dated February 27, 1926. Its headline read:

W. Franklyn Booth’s [sic] Bow Wizardry Astounds

—Left-hand Technique Said Greatest Ever Known—

Described by Artists as Modern Paganini.

There followed lengthy praise of his digital dexterity, his supple bowing arm, and pyrotechnic feats that not even Jascha Heifetz could match. The writer had witnessed him “flitting up and down a famous Stradivarius. For two hours he kept up a running fire of left hand monstrosities without showing the least fatigue.” In superscription William wrote, “This is not an ad. dear it couldn’t be bought at any price.”32

Clare did not reply, but she discussed William’s situation with his sister, Ida Boothe Keables, and made it plain she was not disposed to help him. Her father had paid little attention to her for sixteen years and had no call on her now. She claimed to have little money of her own. “I cannot give to others what does not belong to me.”33

William, sensing reluctance in her silence, wrote again. He did not want to “butt in” on her, he said, certainly not as a physical nuisance. “In fact I have a certain disinclination for the kind of life you are living. I believe,” he added, “that material prosperity killed in you a very great woman.”34

This goaded Clare to write in fury that she had problems too. Her marriage was breaking up, and she was dipping into private resources to assist Ann Austin, Grandmother Snyder, and David. As far as helping him was concerned, she felt “no love towards anyone from whom there has come none.”35

William’s third letter was full of wounded dignity, but he expressed sympathy for her situation, which he had not known about. “It all seems such a pity.” He had not meant to beg money from her, nor would he permit his siblings to interpose for him. “I am not a pauper … You are the last person in the world to whom in the case of necessity I would make an appeal.” What really concerned him, as his life approached its end, was the resentment she and David showed towards him, as a result of their mother’s endless vilifications. “Now dear,” he ended, “don’t worry about me, I am recovering. A few months more will, I believe, find me again fit. Getting knocked as I was is simply a part of life.”36

William Franklin Boothe, c. 1928 (Illustration 13.2)

Clare remained silent. William’s last letter, dated December 4, 1928, was typed by a clearly weakened man. “It’s six in the morning … Rare thing—a storm on the sea, it rained so hard, and my habitation leaks so badly that the combination of the two awakened me.” His mood was nostalgic, and he was full of regret for all their lives gone so awry—Ann rusticating with a small-town doctor, David an embezzler, hiding out in Nicaragua, Clare married to a hopeless alcoholic, and he himself dying in poverty, with his great work unfinished. “Far better would it have been for all of you to have struggled along with that which I could have made. There would have been brought from you all that I know is in you, and David would at least have had to face the problems of life … thinking for himself.” For the good of her child, he could only recommend that Clare stay with George, unless another loving provider was in the offing.

He refused to believe what his sister told him, that “you hard heartedly said nix” to the idea of voluntary help with his medical expenses. Obviously he needed just such help. “My stomach is the despair of my doctors.” The Boothes were providing only a fifth of his “bare necessities,” and he had been forced to sell everything of value, even his precious violins.

How am I going to get along? Damned if I know … if I can only finish my work, then I am ready to go … it seems unfatherly to crowd upon you my troubles when you yourself are knee deep in woe, but you might as well know … I have a presentiment that I won’t hear from David. Why I can’t say … but it just seems that it is not to be my luck. I am dispirited this morning—I should not have written to you in my present mood.

In a shaky hand he signed himself “Your Father.”37

Eight days later, William Franklin Boothe was admitted to Torrance Hospital in Redondo Beach. He died on Saturday, December 15, of pneumonia and “auto-intoxication”—poisoned by substances generated by his own body. He was buried on December 17 at Roosevelt Memorial Park, with neither of his children nor their mother in attendance.38

In January 1929, Musical Courier ran a major obituary calling William Franklin Boothe “a many-sided genius” and “a violinist whose virtuosity was widely acknowledged.” Versa sent Clare his Boothe-Brokaw scrapbook, and a student, Ruth Paddock, in whose house he had lived for a while, followed up with his locket and some personal items. Among them was a carefully kept article entitled “Sex Hunger Insatiable.” Evidently the old roué had retained his libido to the end.39

Miss Paddock also wrote that it was her intention to complete William’s manuscript and do her best to see his name “among the immortals, as is his right.” In December 1931 she placed a copy of the unpublished “Fingered Octaves and Primary Extension Exercises” in the Library of Congress. Reviewing it sixty years later, the eminent violin scholar Josef Gingold confirmed that William Boothe’s exercises were impressive, the work of a man who certainly knew his instrument. But he advised fiddlers not to practice them more than fifteen minutes, for fear of developing tendonitis.40

Clare claimed to have paid for her father’s interment over Ann Austin’s objections. But nine years after William’s demise, John Boothe sent his niece a news item which alleged that she was turning all royalties from The Women over to charity. “If the clipping is true,” he wrote bitterly, “your charity might have reached up to one whose funeral expenses were paid by those who could ill afford them.”41

Perhaps out of guilt, Clare later insisted that little Ann study music. She acquired Bruno Caruso’s Violin Player and Giacomo Pozzano’s The Violisi for her art collection, entered into a midlife affair with the Mexican composer and conductor Carlos Chavez, commissioned a symphony from him, and in her last years grew dependent on classical recordings, played in the solitude of her room as she fought for sleep.

When George emerged from his weeks of isolation, Clare announced her intent to divorce him. Given that his alcoholism was now a matter of record, he made little protest.

On January 31, 1929, the couple signed a separation agreement in which each undertook not to do or say anything to “annoy, vex, or oppress” the other, and to visit only with mutual consent. George promised to pay his wife $2,500 a month until a $425,000 trust fund was in place for her later that year. Custody of their child was to be shared. Even if Clare remarried, George would continue to pay for Ann’s clothing, schooling, and medical treatment. Debts up to $1,500 contracted by Clare before the date of the agreement were also his responsibility.42

Clare moved to a hotel for a few days before leaving for Reno in early February. Soon after her departure, Ann Austin went to the Brokaw mansion to see her granddaughter, as she was accustomed to do freely. But she found that her key would no longer fit the door. George had already changed the locks.43