The Jazz Age … was borrowed time … the whole upper tenth of a nation living with the insouciance of grand ducs and the casualness of chorus girls.

—F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

At a dinner party in the early summer of 1929, Clare Boothe Brokaw met Condé Nast, publisher of Vogue, Vanity Fair, and House and Garden. Emboldened by his Southern courtesy, she said she was feeling empty and directionless since her divorce, and asked if he could find her a position on one of his magazines. Nast had heard this request before from bored society women and usually paid little heed. But Clare’s obvious seriousness, not to mention her beauty, brought an invitation to visit his headquarters.1

Condé Nast Publications Inc. was housed in the Graybar Building on Lexington Avenue at Forty-fourth Street. The beige and white marble Art Deco structure was then the largest office complex in the world, with direct access to the train tracks of Grand Central Station. On its nineteenth floor Clare was interviewed by Vogue’s editor, Edna Woolman Chase, who had worked on the magazine for thirty-four of her fifty-two years.

Wasting no time, she set the job seeker a test: to write the kind of detailed picture captions for which Vogue was noted. Clare’s efforts showed promise, and she was told to return in a few days. But by then Mrs. Chase had left for Paris to see the fall collections, saying nothing about Mrs. Brokaw’s employability.2

Clare had to resign herself to a summer of suspense before the editor returned. Keeping to her Reno resolve to live for herself, she arranged to stay for a few weeks on the breezy shores of Long Island. Since Ann Austin was still in Europe, and little Ann was due to spend August with George, she saw no reason to be marooned with her moody brother in the claustrophobic confines of Sound Beach.3

Soon someone sent word that George was “dreadfully lonely,” unable to “let up on the gin,” and had become an easy prey for “scheming females.”4 This report confirmed what had for some time been obvious to Clare: she could not permanently tolerate sharing custody of her daughter with a father in such mental and physical disarray.

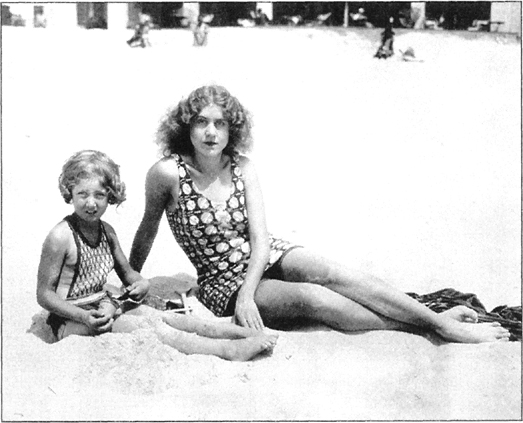

Clare and Ann at Southampton, Long Island, July 1929 (Illustration 15.1)

Bronzed and rested, she moved back to Manhattan in early September, and rented an apartment in the Stanhope Hotel at 995 Fifth Avenue. Only a few doors away stood the mansion she had abandoned just eight months before.

Clare had not heard from Mrs. Chase, but she was still determined to work at Vogue. So after Labor Day she put on a gray dress with white collar and cuffs, went back to the Graybar Building, and persuaded an assistant that she was a new employee. She took a seat at an empty desk in the editorial department and waited for some work to arrive. After a while it did. “I kind of oozed on,” she recalled. “Nobody knew anything about me, not even the accountant.” As a result, almost a month would go by before she received her first thirty-five-dollar weekly paycheck. When Edna Woolman Chase returned and found Clare in place, looking both businesslike and elegant, she assumed Condé had hired her. He, in turn, thought she had.5

The newcomer’s manner struck Mrs. Chase as being “a little grand.” At breakfast, Clare would spread a cloth across her desk and pour coffee from a silver pot. She was accordingly kept busy on a strict diet of captions. There were plenty of them to write, since Vogue was then published twice a month. Ambitious to write at greater length, Clare welcomed the eventual opportunity to do an article on the accoutrements of a well-dressed baby. Her manuscript, entitled “Chic for the Newly Arrived,” warned that a standard twenty-two-inch christening robe, made of the finest batiste edged with Valenciennes lace, and worn over a slip of crêpe de chine, could cost “a great deal more than mother’s latest from Chanel.” Clare went on in deadpan style to describe other extravagant garments and excesses, such as an appliqué-trimmed crib and a lapin-lined perambulator. She recommended edible toys, because “babies have a passion for playing with their food and eating their playthings.”6

Far from objecting to her archness, Mrs. Chase spread the piece over five pages, illustrated with pictures of bonnets, bibs, booties, and bassinets. Three years after its publication (without her byline), Clare boasted to an interviewer that her maiden article in Vogue was “still pointed to as a classic by merchants of the Wee Garment trade.”7

In another assignment, covering a new line of lingerie, she flippantly described one filmy pair of drawers as “toothsome” and was horrified to discover that a copy head had sent it to press. Mrs. Chase saw her “pumping down the hall” to rescue the embarrassing phrase.8

Notwithstanding her cultivation by Edna Woolman Chase as a young writer of promise, Clare struck up a warmer relationship with Margaret Case, Vogue’s society editor. The latter’s eye for style was reputedly so unerring that even the fashion editor, Carmel Snow, went to her for advice. “Now what is the story about gloves this season?” Clare heard Miss Snow ask one day. “Leave the buttons open, and wrinkle about the cuff,” replied the oracular Miss Case.9

“Maggie,” as intimates called her, both predicted and influenced dress and decorating trends on both sides of the Atlantic. She showcased Syrie Maugham’s all-white room in one issue and a spare but perfectly appointed servantless apartment in another. As the magazine’s chronicler of comings and goings, she had real power, and she used it to persuade socially prominent women to pose in glamorous gowns of Vogue’s choosing. Yet at thirty-eight she remained a journalist at heart and enjoyed nothing so much as rushing off to Europe with her favorite photographer, Cecil Beaton, to capture a Spanish religious festival or an English royal spectacle.

Clare, whose taste in most things was expensive but unsure, learned much from Maggie Case. The editor believed that “style trickles down” and was generous with advance fashion tips. Surprisingly, her own clothes were staid, even mousy. There was something spinsterishly stiff about her and her way of falling asleep bolt upright. She became the prototype of all the uncompetitive, well-connected women Clare would cultivate and use over the next fifty years.10

Just down the corridor from Vogue stood the offices of Vanity Fair, Condé Nast’s prize gift to the haut monde. Since its launch in 1913, the periodical’s circulation had not advanced beyond 90,000. Time disparaged it as a “glossy ‘smartchart’ ” and said that “no magazine prides itself more on the chic modernity of its readers.”11 These consisted of a small but potent concentration of the more literary and artistic members of society as Black Thursday loomed in the last week of October 1929. To Clare, still scribbling service copy at Vogue, the famous monthly was simply the most desirable and sophisticated next step she could imagine, perhaps in the remote future when her byline might mean something.

Between Vanity Fair’s strikingly original covers were found such stellar short story writers, essayists, poets, and political commentators as Colette, D. H. Lawrence, Noel Coward, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Robert Benchley, and Walter Lippmann. Among the painters and photographers were Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, the Mexican caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias, Man Ray, and Edward Steichen.

Editor for the past fourteen of its sixteen years was Francis Welch Crowninshield, a lean, silver-haired bachelor with the elaborate manners of an Edwardian gentleman. In spite of his Brooks Brothers suits, “Frank” had avant-garde tastes and was a habitué of New York’s modern art galleries. Since Condé Nast knew little about this world, he gave his editor carte blanche in making Vanity Fair something of a monthly gallery.

Crowninshield’s office was as baroque as his personal appearance was austere. Beyond a door decorated with green figures on silver leaf, he sat at a lacquered desk against a background of shimmering Chinese wallpaper. He was assumed to be homosexual, although he vaguely informed Edmund Wilson that he had “a girl who came to see him once a week.” No doubt existed of his nose for talent, and he frequently prowled through Edna Chase’s adjacent domain, sniffing it out. Earlier in the decade, the scent had led to Dorothy Parker. Now it brought him to the fragrant Clare Boothe Brokaw.12

When first presented to her I thought her the usual Dresden-china society figure, a shepherdess with pretty teeth, large, round blue eyes, and blonde hair. She had, too, les attaches fines, as her neck, ankles, and wrists were singularly fragile. She was, altogether, a bibelot of the most enchanting order … her skin possessed a curious kind of translucence, as if some shining light beneath it were causing the faint, pearl-like aura which seemed to surround her.13

Clare immediately ingratiated herself by offering Crowninshield a hundred article ideas for Vanity Fair. Astounded at her speed and facility, he patronizingly joked that she must keep “a clever young man” under her bed.14 She filed the remark in feminine memory and left it to him to make the next move.

The Wall Street crash of October 29 was still reverberating in the world’s ears when, the next day, a telegraph sent to the Stanhope Hotel invited Mrs. Brokaw to see Vanity Fair’s managing editor, Donald Freeman, the following morning at 11:30.

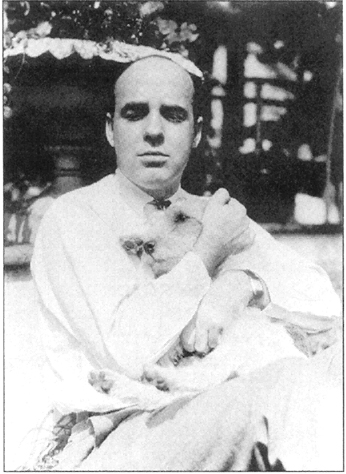

Clare knew the twenty-five-year-old Freeman by reputation. He was a Columbia graduate who had studied in Vienna and spoke German and French fluently. For transatlantic promotion of the work of such writers as André Maurois and Paul Valéry, he had been made a member of France’s Légion d’Honneur. In person he was unprepossessing, with a receding hairline and a shape that revealed a weakness for sherry-laced soup, beer, and banana splits. Nevertheless, Clare liked his quiet solidity, and though he was eight months her junior, she recognized Freeman’s educational superiority and editorial flair.15

He, in turn, had been aware of Mrs. Brokaw’s fine looks and candid gaze from the time of her arrival in the Nast organization. As they talked he was dazzled by her ready wit, originality, and intellect equal to his own. More important, he sensed her creative potential and relished the chance to play Pygmalion.

All that remained, after Clare left his office, was for Freeman and Crowninshield to persuade Edna Woolman Chase to part with her latest editorial assistant. This did not prove difficult, since Mrs. Chase, along with millions of other Americans, was currently preoccupied with disastrous personal losses on the stock market.16 Few anticipated the extent of the debacle in which the United States lost a staggering $30 billion—in admittedly overheated stock values—twice the national debt and an amount equal to the entire cost of World War I.

Clare suffered little, thanks to George Brokaw’s canny foresight. From her $25,000 income, she dropped only $1,200 a year of United Cigar Store stock, leaving her $425,000 trust fund virtually intact. As the depression set in, she had, at worst, the minor inconvenience and expense of a precipitous descent of hemlines, almost to the ankles.17

Donald Freeman, c. 1931 (Illustration 15.2)

By December, Clare had moved to Vanity Fair as a junior editor, at an annual salary of $1,820. She shared a large, sunny office with the drama critic Margaret Case Morgan (no relation to Vogue’s society editor). Freeman worked right next door. Under his tutelage, Clare began proofreading, arranging interviews, and setting up photographic shoots. Keen to learn all aspects of the job, she honed her schoolgirl literary skills on incoming manuscripts. Frank Crowninshield declared a plot she outlined for a blocked author to be “worthy of de Maupassant or Turgenev.” With the aid of a French dictionary, she translated short stories by Frédéric Boutet and made what Donald called “a masterpiece” of an essay on cats by Paul Morand.18

The already captivated Freeman encouraged her to start writing articles of her own. She worked on them in the early morning hours, and utilized Saturday afternoons for library research. What leisure time remained she spent with her mentor. Predictably, his role expanded from that of dinner, movie, and theater escort to that of lover. “As soon as he got me on my feet,” Clare later wisecracked, “he wanted me on my back.”19

Donald shared a weekend cottage in Rhinebeck with his mother and unmarried sister, Gladys. During the week he lived in a book-lined apartment on East Nineteenth Street. From there he would take Clare to evenings with his many publishing acquaintances, including the wits of the Algonquin Round Table. His closest friend was George Jean Nathan, Vanity Fair’s theater critic, who suggested that Clare drop “Brokaw” from her professional byline. But she was not yet ready to accept this advice.20

So long as it suited her, she concealed an abhorrence for Donald’s protuberant belly and grubby fingernails, as she had once hidden her contempt for George’s childishness and drinking. Marriage had given her access to money and high society. An affair with her managing editor promised contacts more pertinent to present purposes. Yet she did not see herself in what she humorously called a “jungle” job, “the kind you hang onto with your tail.” If it had been, she would not have risked Donald’s wrath by flirting with visiting aristocrats such as the Earl of Warwick and Grand Duke Alexander of Russia, who called her his “Dearest Doushka” and boldly kissed her when he submitted a manuscript on world peace.21

Vanity Fair published the first of Clare’s extracurricular pieces in August 1930. It was a lampoon on upper-crust chat, called “Talking Up—and Thinking Down” and subtitled “How to Be a Success in Society Without Saying a Single Word of Much Importance at Any Time.” The opening paragraph heralded its theme:

Too much has already been written about the dead or dying art of conversation. Drawing-room cynics and critics of society assert that the fine art of persiflage and repartee, of making epigrams and bons mots, of Pope’s “feast of reason and flow of soul,” which flourished until Nineteen Hundred in the salons of France and England, received its death blow at the dinner tables of the modern capitals.

Ignoring her own stricture, Clare proceeded to criticize middlebrow talkers for going on at length and without originality about golf, bridge, dogs, racehorses, the stock market, Prohibition, high rents, politicians, absent acquaintances, and sex. She was no less critical of those who affected culture but not too much of it: people who might discuss art, stopping short at Rodin, philosophy only as popularized by George Bernard Shaw or Will Durant, and opera if sung by Jeritza. They might cautiously allow Hemingway a word or two but would not mention Joyce, Proust, Spengler, or Einstein for fear of being thought “highbrow” and jeopardizing their social status.

Clare’s long-sentence style was marred by an excess of adverbs, and she petered out of original ideas midway. But “Talking Up” was a creditable début, even though its skeptical tone was stronger than Vanity Fair’s customarily cool, urbane “voice.”

A literary agency was impressed enough to propose handling foreign publication of all her articles, and any fiction she might write. Donald telegraphed the news, adding that he hoped it would inspire her to “work hard tonight.” This exhortation became a refrain in their relationship over the next two years, as he groomed Clare not only for editorial stardom but for a literary career in her own right.22

Vanity Fair at the beginning of the Thirties differed little in its basic format from Vanity Fair at the start of the Twenties. Unaffected, as yet, by the looming Depression, it still portrayed an America in transition from the age of robber-baron vulgarity to one of more democratic, albeit metropolitan elegance. If its covers in 1930 no longer depicted cloche-hatted young women being wooed against abstract backgrounds of purple pods, or banjo players and Harlem dancers on collages of geometric shapes, its fifty inner pages (routinely preceded by forty of advertising, with forty more at the end) still divided into eight departments that Frank Crowninshield saw no reason to change. They were “In and About Theatre,” “Concerning the Cinema,” “The World of Art,” “The World of Ideas,” “Literary Hors d’Oeuvres,” “Poetry and Verse,” “Satirical Sketches,” and “Miscellaneous”—covering sports, games, music, and fashion for both men and women.

“Ideas” was the only part that allowed for serious discussion of controversial views. An article by Aldous Huxley, published before the crash, had presciently cautioned that the fruits of Western industrialization were a temporary phenomenon. “We are rich, because we are living on our capital. The coal, the oil, the nitre, the phosphates … can never be replaced.”23 But on the whole the magazine tried to chronicle the times without excessive economic or political comment. Literary contributions, many of them from Europe, outnumbered current-affairs columns by as much as ten to one when Clare joined the staff. These proportions would alter dramatically in the more prosaic decade ahead, as readers began to look beyond diversion and amusement, and to desire the status of being well informed.

Wall Street’s collapse affected Vanity Fair first of all in its paying pages. No longer was it possible to fill two thirds of them with advertisements for Cartier jewelry, Guerlain perfume, and $25,000 Mason & Hamlin pianos. Readers were still urged to sleep on the finest linen, dine with the best sterling silver, and cross the Atlantic on the grandest ocean liners. But when Tiffany & Co., long a staple at the front of the book, symbolically gave way to Listerine, circulation would begin to decline.

That day, however, was still some way off in August 1930, when Clare published her first contribution to “We Nominate for the Hall of Fame.” This was a regular among Vanity Fair’s miscellaneous features. The format called for laudatory biographical paragraphs beneath portraits of notable people in the arts, sciences, sports, and business spheres. Clare’s assigned subject was Henry Robinson Luce.

She had not yet met the wunderkind publisher and knew little about his private life, hobbies, or eccentricities. “Does he save string, or raise fish?” she asked his colleagues and friends. No, they said, Luce did nothing but work. “What a dreary man,” she thought as she struggled to write a convincing citation.24

Because he originated the news-magazine idea; because at the age of 32 he is the successful editor and publisher of Time and Fortune magazines; because he was born in China; because he was once a humble newspaper reporter on the Chicago Daily News; and lastly because he claims that he has no other interests outside of his work, and that this work fills his waking hours.

Why being born in China, becoming a reporter, and having no outside interests qualified Luce for laurels was hard to explain. Clearly, Clare did not lean towards adulatory prose. She preferred satire, and to showcase her gift for it, she persuaded a reluctant Frank Crowninshield to run an antidote to “Hall of Fame.” It was called “We Nominate for Oblivion.”

The first casualty of her concept was the tabloid publisher Bernarr Macfadden, nominated for having America’s “raciest stable of cheap magazines.” It was an unfortunate selection, since Macfadden was a customer of Condé Nast’s Connecticut printing plant. He immediately canceled a $50,000 contract. Nast was furious and insisted on vetting all future candidates for “Oblivion.”25

Perhaps as a result, Clare’s abrasive feature ran irregularly. The novelist Elinor Glyn was included for starting “a saccharine and untrue school of literature,” Huey P. Long for spending state money “like an oriental potentate,” Cecil B. DeMille for creating “distorted values of love, high life and wealth,” Queen Marie of Romania for her “devotion to press-agentry and boosting of cold creams,” Aimee Semple McPherson for depending “more on sex appeal than spirituality to bring sinners into the fold,” Al Capone “because he turned out to be a small-time social climber,” and Adolf Hitler “because his Jew-baiting campaign is medieval in its intensity.”26

“We seldom get orchids … from ‘Fame’ candidates,” Clare noted with glee, “but we do get bunches of lovely scallions from ‘Oblivion’ victims.” The objection was always the same: they did not mind being criticized so much as having to keep company with the others.27

At an editorial meeting, Crowninshield voiced disapproval of the creeping harshness—what Paul Gallico called Clare’s “guts and toughness”—that he detected in his once-benign magazine. It was bad business policy, he felt, to vilify people in print. “Crownie was pretty much of an old lady,” Dr. Mehemed Agha, Vanity Fair’s art director, remembered years later. “He was terribly afraid of offending anybody … or doing anything that wasn’t dignified and decorous. Clare on the other hand was a satirical person, with a rather cruel approach to people and things, a debunker.” At the time, Agha could only protest, “We shouldn’t make everything mild and milk toasty.” Crowninshield was not persuaded, and after running ten times in twenty-two months, “Oblivion” was dropped for good.28

The name of Clare Boothe Brokaw joined those of Ogden Nash and P. G. Wodehouse on the list of top contributors to Vanity Fair in September 1930. Her essay that month, “The Dear Divorced,” considered differences between agreeable and disagreeable marital breakups. She had nothing original to say about rancorous splits but wrote approvingly of “good lovers” who, “lacking the energy to become good haters, part in the nick of time, hopeful of becoming good friends.” In an age when divorce was considered as mostly destructive, this wry idea of parting in order to salvage a relationship was distinctly new.

A month later Clare published “Ananias Preferred,” a tongue-in-cheek paean to the well-told lie. Without deception, she argued, diplomacy might fail, governments fall, and social structures atrophy. “Lying increases the creative faculty” in man, lessens friction, and, effectively done, buttresses the ego. Writing as an unacknowledged expert, she cautioned that successful prevarication requires a faultless memory, in order to keep track of untruths told.

“Your article on Ananias has created quite a furor in the office,” Donald Freeman informed Clare. “We all agree that this is the best piece of writing you have ever done. Mr. Crowninshield is more than enthusiastic.” Indeed the latter was so impressed that he immediately promoted his twenty-seven-year-old discovery to associate editor.29

Clare’s November piece, “Bachelors Do Not Marry,” was pedestrian by comparison. She seemed to have Julian Simpson in mind as she brusquely condemned men who hover eternally on “the matrimonial brink … their eyes gleaming with half-formed resolve.” Why, she asked Donald, did she sound so “hard-boiled” in print, when in her heart she felt “compassion and affection for everyone”?30

Every Wednesday at Vanity Fair, Frank Crowninshield gave a lunch for editorial staff. More often than not, the menu consisted of his favorite eggs Benedict and chocolate éclairs, sent up from the nearby Savarin restaurant. Clare would ostentatiously bring her own spartan snack of melba toast and salad, making other women feel “like harvest hands” and calling male attention to her streamlined figure.31

There were always two or three special guests at the table. Out-of-town writers such as Thomas Wolfe and Sherwood Anderson were captivated by Crowninshield, a superb raconteur. He gossiped so entertainingly about dinners at Mrs. Vanderbilt’s, or balls at Mrs. Twombley’s, that they felt like Park Avenue insiders and agreed to write for lower fees than they might earn elsewhere.32

Clare had her own experience of Knickerbocker society, and hit on the idea of writing a series of satiric, interrelated short stories about its stalwarts. Twelve appeared in Vanity Fair. With superabundant energy she would complete eleven more, in the hope she might someday collect them in a book.

Each story exposed or mocked the snobbery, affectation, cruelty, bad taste, and carelessness of the old and new rich. Clare’s “voice” was in turn melodramatic, sardonic, farcical, and bathetic. Few subjects were deserving of charity, and her distaste for the vacuousness, even malevolence, of the lives described was all-pervasive.

She spiced the bland pomposity of New York and Newport hostesses and their “stuffed shirt” husbands with a variety of seedier characters: a burnt-out painter, a lascivious salon musician, an impoverished nobleman, a venal doctor, a philandering sportsman, a lovelorn stockbroker, an opportunistic flapper, and an assortment of jaded dandies, débutantes, and divorcées.

Easily recognizable real people appeared caricatured or thinly disguised. Mrs. Reginald Towerly in “Life Among the Snobs” was clearly Alva Belmont. Hugo Ashe, the feared theater critic in “Two on the Aisle,” amounted to a surprisingly sympathetic portrait of the New York Times columnist Alexander Woollcott, and Flora Arbuckle, a fat party giver in “Exhale Gently” and “The Ritz Racketeer,” parodied Elsa Maxwell. Alfred Clothier, in “The Catch,” was a carbon copy of George Brokaw—a middle-aged heir to a large fortune and a target for marriage-minded young women.

Season after season for twenty years, Clare wrote, Clothier had stood “on the stag line of any important coming-out party, his face as blank as his immaculate shirtfront, his delicate hands alternately thrust into his pockets or fumbling self-consciously with his pearl and platinum watch chain, as he furtively eyed the more full-blown of the buds.” A solitary patron of speakeasies, he was “as ashamed of his taste for drink” as he was of his sexual appetites.33

Also partly autobiographical was “Ex-Wives’ Tale,” in which she recounted the “most fashionable divorce of the season.” After six years of marriage, her alter ego protagonist had left a rich, dull husband for only one reason—boredom. Back from Reno, she moved into a modernistic apartment, became an interior decorator, and started dating again. Her hopes of romance, however, were thwarted by men who, in Clare’s coy phrase, were not “as much concerned with her ultimate happiness as with their own immediate desires.” This was especially true of Bela Dárdás, a laconic pianist whose hands hung “like tired lilies upon the darker ivories” but who was an Olympian in the bedroom. After one night of “grand amour,” he left her “quivering from … delicious contact with genius”—and never came back.34

Clare usually had free rein in writing what she pleased for Vanity Fair, so she bridled when asked to produce a pair of service articles on backgammon. She told Donald Freeman that if she wrote like an expert she would be expected to do more, and if she deliberately made them amateurish, her reputation would suffer. He pointed out that since the request had come from Crowninshield, it might be good office politics for her to comply. Reluctantly she deferred, but published both pieces under the pseudonym “Julian Jerome.”35

Every day Clare felt more confident of her powers. Margaret Case Morgan came to work one morning and “found that she was employing my secretary and I was employing hers.” Clare had lured the former away by paying twice the usual salary out of her own pocket. On another occasion Mrs. Morgan left a pair of complimentary first-night tickets on her desk while she went to lunch.

When I looked for them around five-thirty, they were gone. After a frantic and vain search, I called up the press agent, who agreed to have duplicates for me at the box office that night.

When my date and I walked down the theater aisle with my duplicate tickets, guess who had the real tickets and who was occupying my seats? Right. None other than Clare Boothe and escort. I was so mad that I merely said to her, “Enjoy the play, dear,” and stalked back up the aisle. My date and I went to the movies.

Next morning in the office Clare said, “But you left the tickets on your desk, so of course I thought you didn’t want them!”36

It was becoming evident that whatever Clare desired, she simply took, or tried to take. Condé Nast told Mrs. Morgan that she had even offered to buy a controlling interest in his company.37

Ironically, only Donald stood between her and the job she now lusted for: that of managing editor.