I hope I shall have ambition until the day I die.

—CLARE BOOTHE LUCE

Shortly before six on Friday evening, June 24, 1932, Clare Brokaw passed through departure gate 34 at Grand Central Station and walked along a red and gray carpet emblazoned with the logo of the Twentieth Century Limited. A reserved “roomette” awaited her in a polished steel Pullman, surrounded by clouds of billowing steam. Her destination was Chicago, where delegates from all over the country were gathering for the following week’s Democratic presidential convention. She had two reasons for joining them: first to be an observer for Vanity Fair and second to work as a lobbyist for the New National Party, a pro-Repeal, anti-special interest organization. This fledgling group, formed earlier that year, hoped to influence both Democratic and Republican platforms and to recruit disaffected idealists, with the eventual aim of becoming a third party.

Clare knew no one onboard and dined alone. At Albany she received an affectionate telegram from Frank Crowninshield. “Can you return at once. I find I am too lonely without you.” Before retiring for the night she made a diary comment about her present assignment. “I have a feeling that this will prove something very definite one way or another in my life.”1

Indeed it promised to be both professionally and romantically significant. Not only would Chicago see the deepening of her political consciousness, but a man awaited her there, by far the most powerful and sophisticated she had yet charmed.

For the last month or so, she had been having an affair with the Wall Street speculator Bernard Baruch. Rumored to be the fourth richest man in America, he was a perennial adviser to presidents and a well-known admirer of intelligent women. Unfortunately for Clare, he was sixty-one years old and married with three children. His alcoholic wife shared neither his Jewish faith nor—Clare assumed—his bed, yet he remained faithful to the ideal if not the practice of conventional family life. Clare therefore had to settle for the belief that he cared for her as much as it was possible for “one of his vintage to care for one of mine.”2

She was drawn as usual by the triple attributes of money, eminence, and seniority. In looks, intellect, Southern gallantry, and an engaging, naive egotism, Baruch reminded her of her father. Unlike William Boothe, however, he considered himself an effective political operator. Even as Clare’s sleeper sped her towards him, he was closeted in the Congress Hotel plotting his role in the upcoming proceedings and trying to figure out who would emerge as the Democratic candidate. He had telephoned her the night before to complain, “All is still confusion.”3

The train drew into La Salle Street station at nine o’clock next morning, in stiflingly humid weather. Clare had booked a room at the Blackstone Hotel to be near Condé Nast and his young wife, Leslie, but she went first to Baruch’s suite.4

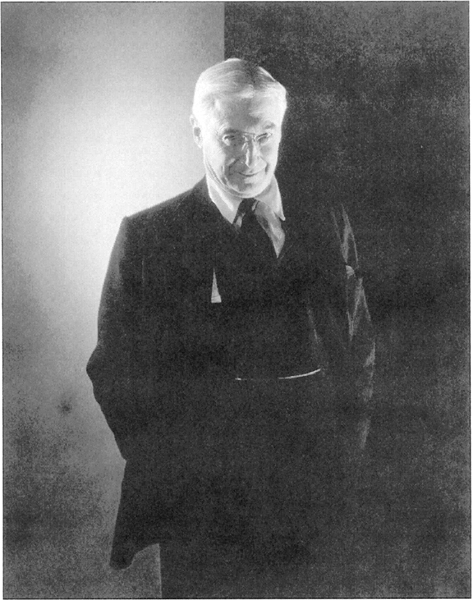

Though “Bernie” or “Barney,” as friends called him, was thirty-two years her senior, he was as vigorously flirtatious as a man half his age. With his six-foot-four-inch impeccably tailored frame, handsome head of copious, centrally parted white hair, and twinkling blue eyes, he was a dominant figure in any assembly. His mother had told him in childhood that “the blood of kings” flowed in his veins, and the majestic confidence this instilled stayed with him.5

Bernard Baruch Photograph by Edward Steichen, 1932 (Illustration 17.1)

Dazzled by Clare’s physical and mental effulgence, he saw her as someone not quite earthly, coming into his life in an aura of light and “dancing on the beams.”6 This morning, since there were other people in the room, he welcomed her affectionately but formally. In a gesture towards her writing talent, he asked her to help his industrial counselor, General Hugh Johnson, compose a statement of policy recommendations for press release. The baggy-eyed veteran was a man of flamboyant high spirits—the result of his steady intake of them, as Clare soon discovered.

While she sat typing, a succession of influential men came by to solicit the opinions of the sage. Among them were William Allen White, vice president of the Baltimore Sun, Mark Sullivan, author of the best-selling Our Times, a six-volume history of the United States, and Walter Lippmann, star columnist for the New York Herald Tribune. Clare already knew Lippmann as an occasional Vanity Fair contributor and found him quietly appealing. Frank Crowninshield had noticed that “the impact which she made on men of that type had the effect, approximately, of a queen cobra on a field mouse.”7

She extracted a promise from Lippmann that he would join the New National Party if—God forbid—the arch-liberal Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt of New York won the nomination.8

Vanity Fair had begun to weigh the year’s potential presidential candidates as early as August 1931, in a monthly feature listing their “Credits” and “Debits.” The magazine’s newfound interest in public affairs had grown to the point that it would print only two nonpolitical covers in 1932. Just two months before it had published a provocative article by its major political writer, John Franklin Carter, entitled “Wanted: A Post-War Party.” Carter proposed that this new party should adopt a platform of ten major reforms. These included repeal of Prohibition, repeal of the protective tariff, measures for extra revenue including a liquor tax, and restored relations with the Soviet Union. In tacit support of Carter’s program, the editors of Vanity Fair invited readers to submit other recommendations and warned that voter inertia could only worsen the current economic paralysis.9

Readers had responded so enthusiastically that the indefatigable Carter decided to form the New National Party himself. He assumed the title of president and recruited Clare as unsalaried executive secretary. The New York socialite Mrs. Harrison Williams became the party’s chief financial backer and its official representative at the Republican National Convention. Frank Crowninshield was disconcerted when Carter had the temerity to open NNP headquarters a few doors from Vanity Fair in the Graybar Building. The prospect of two such ornamental ladies as Mesdames Brokaw and Williams deserting the haut monde to go fund-raising and “shouting in public” appalled him. If they must swing a political sword, he hoped it would be one “forged by Cartier.”10

The embryonic organization needed a potent, attention-catching slogan, and John Carter came up with the phrase “A new party for a new deal.” Clare acknowledged his authorship at the time in a letter to Donald Freeman, but in later years she gave herself credit for the last three words.11

Meanwhile, her education in public affairs had progressed during pillow conversations with Bernard Baruch. She adopted his philosophy that legislators must balance budgets, spend the largest part of revenue on defense, and encourage private enterprise with low taxation. These were typically the views of a conservative Republican, yet Baruch came close to socialism in his simultaneous advocacy of a national health insurance program.

Fortunately for Clare, Baruch’s lifelong identity as a Democrat did not preclude a favorable interest in the NNP, and he had asked General Johnson to draw up a prospectus for it. Several of his own strictures about Washington’s traditional ways of doing business found their way into the document. Many of them have a familiar ring to modern ears, particularly the accusation that Congress had failed both to cut unnecessary spending and to raise necessary taxes, because of pressure by lobbyists and vocal minorities. If neither major party was going to address such issues in 1932, the prospectus threatened, then the NNP would encourage an independent candidate to enter the race and field one of its own in 1936.12

Carter’s latest Vanity Fair piece, also editorially supported, had the headline “Wanted: A Dictator!” The text envisioned a new President with quasi-wartime powers to rescue America’s finances “from the nerveless hands of a lobby-minded Congress.” While incendiary, the suggestion was not unprecedented. Senator David A. Reed of Pennsylvania had already cited the need for an American Mussolini to tackle the country’s ills.13

Well in advance of Monday’s convention opening, Baruch had made it clear to Democratic Party officials that if they chose Roosevelt as their presidential nominee, he would not contribute financially or otherwise to the campaign. While conceding that the man from Hyde Park had been a fairly competent state executive, he agreed with H. L. Mencken that Roosevelt was “too feeble and wishy-washy to make a really effective fight” for the White House.14

Al Smith, the four-time former New York governor and the party’s unsuccessful candidate in 1928, was Baruch’s first choice. But Smith seemed reluctant to run again. Other credible aspirants were House Speaker John Nance Garner of Texas, William McAdoo and Newton D. Baker, both Cabinet officers under Woodrow Wilson, and Governor Albert C. Ritchie of Maryland.15

A majority of the delegates arriving in Chicago were committed to Governor Roosevelt, but he was still short of the two-thirds margin needed for victory on the first ballot. Aloof from the fray in New York, Carter wrote advising Clare to be general rather than specific about the NNP’s aims as she proselytized among disaffected Democrats. He felt that their best chance was to go after Huey Long’s machine in Louisiana. “If we can break the Solid South, we will have split the whole system of Party Government in this country at its roots.” A grateful nation would someday erect a monument to her, he said, for the important work she was accomplishing.16

A storm broke on Sunday night, reducing the temperature by nineteen degrees. Monday’s Chicago Tribune published the statement Clare had helped prepare, in which Baruch called for an immediate cut of $1 billion in government expenditures to save Americans from becoming “slaves chained to the oar of our economic galley.” The metaphor certainly sounded like hers.17

For the next four days Clare dutifully “milled around among the delegates.” She courted members of Congress and other important Democrats, including former Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, Mayor Jimmy Walker of New York, James Forrestal, and Will Rogers. In addition she lectured a meeting of Junior Democrats, wrote and typed a floor speech for an ambitious young Southern delegate, and reported her doings to Carter. Seeking occasional relief from “politics, endless politics … every moment of the day and night,” she worked on expanding her social horizons, having lunches, teas, and dinners with Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, Mrs. Marshall Field, Admiral Cary Grayson, Colonel Robert McCormick, and other prominent observers. She enjoyed several evenings with Mark Sullivan, who was fast becoming an avuncular friend. They recognized in each other an ability to “wring the essence from the envisioned moment.”18

Balloting at the convention began at 3:00 A.M. on Friday, July 1.19 Over 60 percent of the country’s households were able to hear the count by radio. Clare listened in Baruch’s suite. As dawn came up over Lake Michigan, Roosevelt, after three tries, was still short of the requisite number of votes. Yet no other aspirant came close.

Clare (center, rear) at the Democratic National Convention with Leslie Nast (on her right) and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson (center, front) (Illustration 17.2)

The delegates recessed in exhaustion. Clare returned to the Blackstone and slept all day. Behind the scenes, Joseph P. Kennedy of Massachusetts was persuading William Randolph Hearst of California to move his forty-four delegates from Speaker Garner to Governor Roosevelt. At nine Clare entered the convention hall in time to see the New Yorker go over the top on the fourth ballot. Garner reluctantly agreed to take the vice-presidential spot.20

In his acceptance speech, Roosevelt pledged himself to “a new deal for the American people.” Hearing him appropriate the NNP’s slogan made Clare feel “a little heartsick.” Baruch’s face was white and drawn with disappointment. The “S.O.B.,” as he called him, had triumphed after all. They consoled each other until the small hours of Saturday morning, pondering the potency of the “political virus that gets in men’s hearts and souls.”21

Aboard the train going east on Saturday night, illicit liquor flowed. Newsmen began lauding Roosevelt as if they had never had any doubts about him. Clare observed that these “jumpers aboard” included Walter Lippmann and Herbert Bayard Swope, former editor of the New York World. Baruch, too, had “swallowed his pill,” she noted with some disillusionment, “and now he likes it.”

She slept in her lover’s compartment that night, and circled the page number of her diary as a sign of consummation.22

Back in New York on Sunday, July 3, Clare lunched with “Bernie” and told him, to his distress, that she was going to vote the Republican ticket in November. She then motored to Sound Beach to see her daughter. Ann had been sent to George Brokaw at the end of May, but when mumps broke out nearby, she had temporarily left his custody.

Clare noticed at once that the girl was being corrupted by Ann Austin’s “incessant chatter about money.” So had she been herself in childhood. But there was now a more pronounced note of hysteria in the older woman’s materialism. When Clare tried to moderate it, she touched off a torrent of resentment.23

Dr. Austin, estranged by such outbursts, spent much of his time now away from home, leaving his wife, David, and Riggie to their own love-hate relations. Without his civilizing influence, Driftway seemed polluted by a spiritual blight. Clare felt it sullying her finer instincts and eroding her ambition. Rain fell on the Fourth, imprisoning her in the house. As often in situations of family claustrophobia, she needed to lash out at someone. She chose Donald Freeman, who was innocently vacationing abroad, and sent him a fourteen-page letter full of unprovoked bile.24

After watching damp fireworks, Clare returned to the city and an empty apartment. No message from Baruch awaited her, to her instant desolation. He showed up the following night but was not of much comfort, being distracted by family problems of his own. They spent a self-pitying few hours together, and he left without making love.

Clare burst into tears. Suddenly and with startling clarity, she saw that her life had emotionally “shut down.” The fact was that by now she was seriously in love with Baruch—more in love, perhaps, than with anyone in her life. Deep feminine longings demanded that he bind himself to her by impregnating her. But his age, and family preoccupations, made this unlikely. “I will never have another baby,” she mourned.

Aside from such primary despair, she saw “so many, many handicaps”—domestic, professional, and psychological—to frustrate what Mark Sullivan called her “lust to function.” And so, drunk on brandy, she went unconsoled and inconsolable to bed.25

Her spell of morbidity passed, however, as Baruch’s stellar connections continued to expose her to the movers and shakers of America. “I prefer being alone with brilliant men,” Clare exulted. Those she had met in Chicago had extended her knowledge beyond literature and art, to party politics and economics. She found herself circulating among the foremost practitioners of finance, science, and communications. On July 12, for example, Baruch invited her to his apartment to watch a demonstration of a new broadcasting medium, in company with David Sarnoff. The latter was president of the Radio Corporation of America and personally responsible for the all-electronic beams pulsating from the Empire State Building. They sat watching “a small flickering visual apparatus,” she wrote that night in her diary. Television reminded her of “the early days of the movies,” except that it had “perfect sound.”26

Gossip about Clare and her famous multimillionaire grew apace. Even Franklin Roosevelt began referring to her as “Barney Baruch’s girl.” But then, in late July, Bernie announced that he was going to spend six weeks at a rejuvenating European spa and did not invite her to accompany him. “Oh my beautiful darling,” she wrote in anguish, “if you only knew how unhappy I am that you are going.” She could hardly trail after him, since she was behind with her rent, owed enormous sums to dressmakers, and had begun to receive monthly bills of $465 from her mother “to keep Ann.” Forced to spend an economical vacation, she leased the summer place of her penthouse neighbor Bill Gaston in a remote spot off the coast of Maine. It was called Crotch Island.27

Never was a place more aptly named, for the summer of 1932 turned out to be one of sensual and sexual indulgence. It marked the end of Clare’s youth: in eight months she would be thirty. Whatever her fantasies about Baruch, she had to accept that their age difference precluded a long-term affair. Even the younger men she still attracted (David Sarnoff had tried to force “unwelcome attentions” upon her) could not be expected to pay court for many more years. Julian Simpson still wrote her the occasional love letter, full of memories of “burning desire” and vague suggestions that they meet, preferably on his home ground. The devoted Donald Freeman, just back from Europe, looked “fatter than a pig” and repulsed her with his peeling sunburn and blistered mouth. He tried to “make” her, but she demurred. On July 29 she escaped on an overnight train to Rockland. From there a yellow hydroplane sped her in eight minutes to Crotch Island.28

Gaston’s fifteen-acre property sat in a hillside grove of pines overlooking the harbor and sapphire sea. Lush displays of day lilies, geraniums, snapdragons, poppies, forget-me-nots, veronica, purple heliotrope, and alyssum bordered a small lawn. Paths of crumbled seashells led to the door of a two-story log cabin. Inside Clare found three fireplaces and plenty of comfortable sofas. There was neither radio nor telephone, only a Victrola with a rusty needle.29

A Japanese couple cooked her a delicious lunch of garden vegetables. Then she sunbathed and dozed, as hummingbirds chased bumblebees from fragrant delphinium spikes. In late afternoon she took a launch to the fishing village of Vinalhaven and picked up cables from Baruch. That evening she read a study of Hamilton and Jefferson, and was persuaded that despite her recent Republican resolve, “all fine souls must be Democrats.”30

Next morning she breakfasted and typed letters on a porch profuse with rambling roses. Utterly content, she hoped she had not been rash in inviting three men in succession to share this verdant tranquillity.31

The first to arrive, on August 1 for a four-night stay, was William Harlan Hale, a twenty-two-year-old Yale graduate and writer. Clare had met him only five weeks before at Horace Liveright’s and been instantly attracted. “He looked like a young eagle coming out of its egg, tall, skinny, a little fuzzy … romantic, sensitive, well-bred.” After a year in Europe, Hale had just published a two-hundred-page examination of historical and cultural trends called Challenge to Defeat: Modern Man in Goethe’s World and Spengler’s Century. At Clare’s request, he was now writing articles for Vanity Fair.32

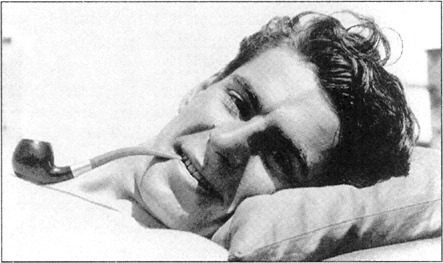

William Harlan Hale

Photograph by Clare Brokaw, August 1932 (Illustration 17.3)

She was not the first older female writer to take an interest in him. Recently in Berlin, Hale had had an affair with Katherine Anne Porter. Though twenty years his senior, the beautiful author had become so enamored she had lent him money from a Guggenheim grant to facilitate his return to New York. Miss Porter had mixed feelings about his current work. Vanity Fair, she wrote, exhibited a “deadly sureness of slickness, smartness,” which the magazine’s airy tone did not quite conceal. “I despise it.”33

Slick it might be, but Hale felt lucky to have a job of any kind at a time when all his college classmates seemed to be among the nation’s 12 million unemployed. As he clambered over the rocks with Clare and caught fish in the cove for lunch, he happily surrendered to her charms. She in turn succumbed to the fertility and amazing maturity of his mind. At night, their suntans glowing in candlelight and firelight, they endlessly discussed literature, exchanged frank anecdotes about their lives, and devised strategies to become famous.

On three nights they made love. Clare reproached herself for being “a terrible little bitch,” having sex with a comparative stranger while cables continued to arrive from her adored Baruch. But this young man made her “tremble at the knees.”34

Before leaving, Hale helped wash and bleach Clare’s hair. He bent over the bathtub, and it occurred to him that the chemical fluid in his hand was highly explosive. All at once he was seized by an ecstatic vision of joint immolation with his “porcelain-eyed bundle of sweetness and light.”35

“It is quiet here,” Clare noted after Hale left. As she lay in bed, the sounds of sighing winds, squeaking branches, burbling water in a rain barrel, and lunar moths bumping against the window screen made her feel frightened and alone. In the morning she must begin the writing she had come here to do: some more short stories and a new novel.36

She was forestalled by the unexpected arrival of her landlord and two loud couples. Powerless to resist their determination to have a riotous weekend, she allowed herself to be swept into a three-day whirl of speedboat rides, tennis, swimming, and drunken dinners. While young Hale had been eager, idealistic, and virile, Bill Gaston was suave, devastatingly handsome, and sexually dangerous. His marriage to Rosamond Pinchot (Reinhardt’s Nun in The Miracle) was breaking up, and he had the reputation of a confirmed womanizer. Between him and Clare the air was always heavy, and she tried to avoid his blandishments. She knew that they were the same kind of animal. “The depths of him are like the depths of me, shifting sands, and we each need an anchor, and we could not anchor ourselves to each other.”37

Resisting Bill now, she told him during a walk in the woods that she disapproved of his rowdy companions. He snapped that in that case it had been a mistake to rent her the cabin. His harshness made her cry, and he tried to kiss away the tears. Her feelings were mixed as she saw him off on the yellow amphibian. Before long she would find herself looking to be comforted by him again.38

Clare spent August 10, the ninth anniversary of her marriage to Brokaw, turning the color of a meerschaum pipe. At 137 pounds she was 12 over what she considered her ideal weight but felt proud of her body’s firmness and health. She was at the height of her appeal to both sexes. Both Condé and Leslie Nast had made passes at her recently, and the latter, at least, was unsatisfied. She wrote to say that she felt a “sharp pain” of desire for Clare. How hopeless it was. Even when they were in the same city, they had managed only one brief interlude together, because of the demands of others on their time. “Darling … why are the forces against us so strong?”39

Another sexual conquest, whom Clare unsuccessfully tried to lure to Crotch Island, was Thayer Hobson, a young vice president at the publishing house of William Morrow. For several months he had been assiduously pursuing both her and the autobiographical novel, “This My Hand,” she intended to write on vacation. She began to suspect, however, that Hobson preferred the role of fantasy lover to that of real one. “Thayer says ‘I adore you’ as other men clear their throats.”40 He was thrice married in any case, so she did not press her invitation, content to maintain an affectionate correspondence in the hope of selling him her manuscript.

Perhaps because of her daytime physical exertions, Clare’s mind was slow and uninspired when she tried to work after dark. She sent off a few stories to magazines that paid better than her own, such as The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post. None was accepted. Nor did the novel, an austere and biting account of her early days with George, go well. Its portraits of herself as selfish and cynical, and of her mother as a venal social climber, were so searing that she abandoned the manuscript after sending Hobson only five chapters.41

She was reduced to “talking the book” when another invited guest arrived. Mark Sullivan, her new friend from the Democratic Convention, was sacrificing the society of his family to be with her. After garrulously summarizing her novel for him, she swung into a marathon description of more recent adventures, including her affair with Baruch. “It’s good to share your soul!” she wrote in her diary that night.42

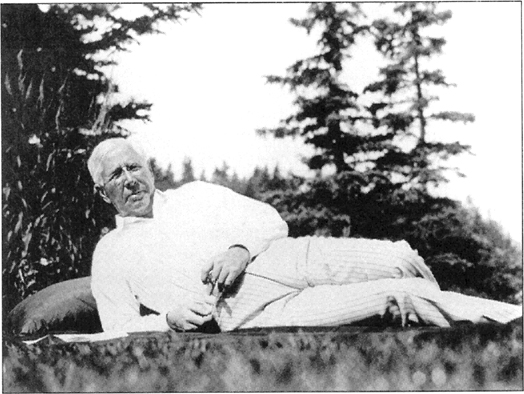

At age fifty-eight, Sullivan relished the confidences of a luminously beautiful and intelligent young woman. In Chicago he had seen Clare’s “glittering and brittle” urban façade. Here he found mellowness and “an exceptional … sinewy mind.” Since he was a close friend of Herbert Hoover, she spent long evenings quizzing him about the making of presidents and the expertise of the men who made them. Inevitably, Sullivan began to display a romantic interest in her towards the end of his five-day stay. But she thought him rather smug, and his shiny red face displeased her aesthetic sensibilities. “So little vanity! And so much conceit!” She was not sorry when the time came for him to go.43

For Sullivan, Crotch Island remained a highlight of his late middle age. In gratitude he sent Clare a precious book inscribed to him by Theodore Roosevelt, and reinscribed from him to her.44

As August wore on, Clare’s feeling of dereliction by Baruch made him all the more desirable. She sent him long, closely typed letters that revealed wistful longings for a future together. He might brood all he liked, she wrote, about “the incongruity, the folly, the utter want of logic in our relationship.” He might also take “that absurd cure at Vichy” in the hope of cooling his ardor. But she predicted that their affair would continue all the same. “Blood-heat has won more arguments than were ever gained by the white-heat of the brain.” Beyond sexual bravado, she felt the need to perform for him.

Mark Sullivan

Photograph by Clare Brokaw, August 1932 (Illustration 17.4)

I shall work very hard because you want me to succeed, and because when I am not violently loving, I must be violently working … One sees so often in life the woman making the man. Now if you will never take your hand from mine, one will see the man making something of a woman. You have taught me beloved to … belong to myself, but the lesson has made me eternally your debtor, your dependent.45

When she received no comparable replies, she grew maudlin. “I feel incomplete, helpless, uneasy … no person, no place, no experience … has significance or interest for me, unless I translate them in terms of you.” A tear dropped on the red enamel space bar as she tapped this, and she made sure he knew about it. She hoped she would not end up “just a girl who takes a typewriter to bed with her.” Her need for him remained intensely physical. “I long to feel myself caught in your arms to put my cheek against yours.”46

Baruch’s cables and notes were circumspect to say the least. Clare could see that he was diffident about putting himself on paper, “afraid so much as to send me a loving word,” in case the endearments fell into alien hands. So cautious was he that he frequently began without a salutation, and signed himself with cryptic initials like “P.K.” for “Pirate King” or the numbers “1, 4, 3” in lieu of “I Love You.”47

There was little time, however, for Clare to pine, for men continued to appear at Crotch Island. Kerry Skerrett, her old Hartford beau, came for an overnight stay, and a soused Bill Gaston and friend, back for a second weekend, separately tried to inveigle themselves into her bed.48

Meanwhile the relationship with Donald continued to sour. Clare’s vitriolic letter from Sound Beach in early July had called him “savage,” superficially sophisticated, and lacking in the “refinement of feeling” necessary to make the transition from love to friendship. In turn, he fired off caustic and querulous notes to Maine. “I suppose you are in the throes of illicit love otherwise I would have had a letter from you detailing your bucolic existence … I am gradually coming to the realization that all is over between us.”49

Ever the managing editor, he badgered her for Vanity Fair articles, assuming that “excursions into sex and nature haven’t dulled the edge of your wit.” He sent best wishes to his “successor,” and coldly signed himself “Freeman.”50

Clare left the island on Friday, September 2, a few days earlier than planned, to avoid a third intrusion by Bill Gaston and to see Baruch, who had returned prematurely from Europe.51

She arrived next morning in a blistering New York, and stoically submitted to having her hair set under a hot dryer before shopping for fall clothes. That night she dined, made love, and talked politics with Bernie. He had pragmatically decided to recast himself as an adviser to Franklin Roosevelt, whom he now thought could win in November. Clare privately admired the mind, if not the socialist politics, of Norman Thomas and thought that the Democratic candidate was intellectually weak in comparison, a regurgitator of the “pablum of nursery liberalism.” But President Hoover’s economic record was indefensible. She could no longer in conscience support him and decided to vote for Roosevelt too.52

Back at Vanity Fair after Labor Day, Clare saw that Bill Hale had settled down and was working conscientiously. She had been thinking of him as a potential assistant editor but now started to have doubts about his all-round caliber. He occasionally seemed gauche, even callow, and she wondered if he had “the imagination, the fire, the inventiveness that I have.”53

She nevertheless continued to sleep with him as well as Baruch that fall. An intriguing diary entry, made after visiting a doctor, implies that she had possibly suffered a recent miscarriage. “There is … no reason why I shouldn’t have an infant he says, and was shocked when I told him that I might have had one.”54

If she nurtured any illusion about Bernie leaving his wife and starting a new family with her, she was soon disabused. Baruch told friends that she was just “a poor little kid,” who had to be kept happy with gifts. Mark Sullivan reported that the financier had frankly discussed the affair with him and said “his heart was not involved.”55

Clare deflected this public rejection by blustering, “Perhaps mine is not any longer involved either.” Therapeutically, she proceeded to scatter her talents and social energy in as many directions as possible. She posed for a Vogue fashion shot by Edward Steichen, had several secret meetings with one of Condé Nast’s competitors (declining a $5,000 increase in salary to work for him), considered taking $20,000 to help former Mayor Jimmie Walker write his autobiography, and started collaborating with Paul Gallico on a play. Dashing from work to lunches, teas, cocktails, dinners, theaters, speakeasies, revues, and nightclubs, she often ended her days in one assignation or another.56

Donald’s jealousy grew to open fury. Vanity Fair staff were privy to loud arguments between him and Mrs. Brokaw. Sometimes he would rush out and berate her from a pay phone, so that he, at least, could not be overheard. He hoped that Clare would be embarrassed by a published rumor that Condé Nast intended to divorce his wife and marry her. But she was not, infuriating him further. When she gave a dinner to celebrate the première of Mädchen in Uniform, a German film Donald had subtitled, he stayed away in a fit of pique. During a climactic spat on September 24, she accused him of using her talents for his own professional advancement.57 He remonstrated a few hours later in what would be his final letter to her.

When I first perceived in you an intelligence which seemed destined to be both creative and flexible, and which you were stifling in an aimless and rather profitless existence, I saw an opportunity to realize by proxy the growth of a career which might make a definite imprint in the contemporary world … You had great charm and breeding, a fine but badly trained mind, and a complete independence from financial cares. Thus you seemed to me an ideal person to encourage and to love. If you will recall a conversation at the Stanhope in the first days, I told you that I would only too gladly step aside when my purpose had been served, when you were sure-footed, aware of your own ability and had carved a niche for yourself of sound proportions … It is only human nature that I should be discarded—what with … men of affairs like Mr. Baruch sighing for your time … It has been only in the past few days that the cloud of my three years love for you has been gradually lifting from the brain of one who has almost been a madman for the whole time. It is not that I found a homeopathic way out for no one will replace you … But I am a philosopher and a much worthier man than you seem to think—really incapable of those black actions which I threatened from the depths of my jealousy, and dread of losing you. As you proceed to greater things, it shall be my satisfaction that in the early days we shared many secrets, and my consolation shall be … your progress to fame and fortune.58

On Friday, September 30, Clare stayed home nursing a cold. That evening, with extraordinary sangfroid, she dined in the company of four individuals who lusted after her—Baruch, Hale, and Condé and Leslie Nast. “We left early,” she recorded in her diary, not saying with whom.

She was in bed on Sunday morning when her telephone rang. It was Leslie with bad news. Donald had been seriously injured the night before in an automobile accident upstate and was in a hospital in Mount Kisco. Clare drove north at once to find him unconscious, eyes black and blue under a swathe of bandages. She was told that Mr. Freeman had hit a stanchion en route to his Rhinebeck house for the weekend. Thrown from his car, he had landed on his head and split his skull.59

For the rest of the day, Clare sat with Donald’s mother and sister, and Frank Crowninshield, listening to Donald breathe. It was evident that he was fading. The thought of his head, which she had so often passed her hand over, “cracking wide open to death” seemed to her a “hideous enormity.” Poor Donald, “so young, foolish, clever, tender, tormented, gay, inspired, ugly, mean, generous.” He had made her life “so intricate, hard, full, and interesting.”60

At five o’clock, while she held his hand, he died. He was not quite twenty-nine years old.61

Numbly motoring back to town, Clare went with the Nasts and George Jean Nathan to her dead friend’s apartment. The sight of his cat, Casanova, upset her but did not prevent her taking Donald’s journals. She began reading them as soon as she got home. Apparently she then destroyed the volumes, for they were never returned to his family. All that is known of their contents is what Clare recounted in her own diary. She claimed that he hardly mentioned her name. Only towards the end did he write of her “meteoric” rise. She noted with some annoyance that he had had several other affairs. “I know he loved me best,” she presumptuously persuaded herself, adding, “and I loved him more than any of the others.”62

Though Clare did not say so at the time, she kept two documents that Donald reportedly left for her that fateful Saturday. One bore her initials and a small, rough drawing of a grave with cross and flowers. The other was an unattributed poem.

There is no virtue in a quantity,

So many hours, so many days of joy

Time is no measurement of ecstasy,…

Be happy then that for a moment’s space

You found, together, love and love’s delight

Implicit understanding and bright grace

About you all the day, and through the night.

For the gay shining interlude you had,

And her remembered loveliness, be glad.63

In old age Clare insisted that the sketch—which has survived—proved Donald had committed suicide over her. But by delivering it along with the verse, he could have meant merely to symbolize the demise of their relationship. His last letter had stressed that he was incapable of “black actions.” Driving into a post, even at high speed, would not have guaranteed death. Deeply disturbed as he was (Nathan confirmed that Donald had been “mad” towards the end), he might have intended not to kill but merely to injure himself, in order to elicit sympathy and perhaps rekindle her love.64

On Monday, October 3, Clare went to St. Thomas’s Episcopal Church on Fifth Avenue and wept over Donald Freeman’s coffin. After dining alone at a hotel, she visited Bill Gaston in his new apartment and stayed until four in the morning, making love. She needed comfort, she told herself, because she was “weary of looking on the face of death, and wanted to feel alive.”65

Next morning at the office, she kept expecting to see her former mentor in the corridors, his underlip thrust out, his stomach held between his hands.66

At the funeral on Wednesday, Clare walked up the nave with Donald’s mother, as though she were his widow. Thus she appeared to give him in death the commitment she had denied him in life.