An unsatisfied woman requires luxury.

—ANDRÉ MALRAUX

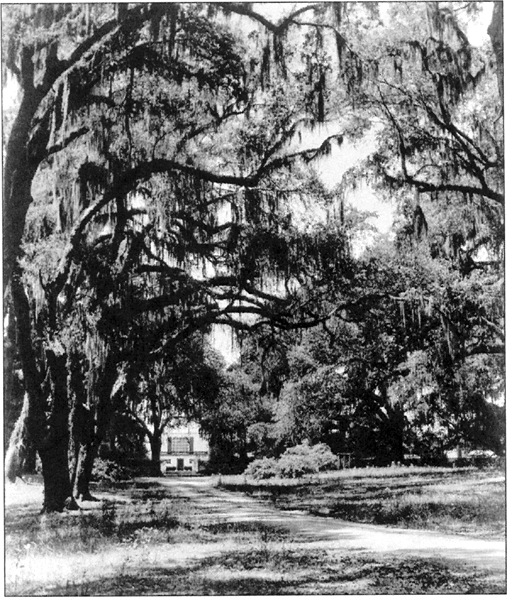

Tired yet exhilarated by their work on The Women and Life, both Luces looked forward to a recuperative first stay at Mepkin in the new year of 1937. They had completed its purchase the previous April and hired an up-and-coming architect, Edward Durell Stone, to design a house and three guest cottages in spare, modern style. These would replace a mansion of 1906 vintage that they had originally overlooked because of the dense shield of ancient live oaks surrounding it.

Forty laborers working in shifts had started to demolish the old house and lay the foundations of the new. After restoring stables and kennels, they installed power lines and piped in fresh water to replace that from the pungent artesian wells. Clare, who was always fascinated by construction sites, had taken some quick trips south to monitor progress. Fighting off swarms of mosquitoes, she had sat under the trees and watched haulage trucks struggle through the red mud of summer rains. At last she was building her own estate and gratifying her “Napoleon complex.”1

To serve as the main residence, appropriately named “Claremont,” Stone built a two-story, whitewashed brick house with a central staircase. An arcade connected it to three air-conditioned guest cottages, eventually to be embellished with clumps of bamboo, pale wisteria, and lush fig vines. They were named “Strawberry,” “Tartleberry,” and “Washington,” after other plantations along that stretch of riverbank. Each consisted of a porch, terrace, two bedrooms, and a sitting room facing the water. From all of them guests would be able to refresh their winter-weary eyes with views of lush swards of bright green ryegrass, herons stalking the old rice marshes, and hundreds of fuchsia azaleas, as well as Clare’s favorite white camellias. Diners at Claremont could look out through huge picture windows and see the setting sun, a ball of flame in the dark Cooper River.2

Both house and cottages were furnished in the bland contemporary style that Clare preferred: chunky armchairs and couches, mirrored screens, small white desks, block-printed drapes, and wall-to-wall carpeting. Bowls of Cherokee roses perfumed the rooms, and sheets were lavender scented. Gladys Freeman, sister of the dead Donald and now working for a Manhattan interior design firm, helped create some fairly obvious color schemes, such as patriotic red, white, and blue wallpaper and blue linen upholstery with red piping for the Washington cottage. In Tartleberry she made a concession to the past with lace-hung twin four-posters and an antique dressing table.3

Mepkin’s streamlined architecture displeased local gentry, and they began referring to it as “the Luce Filling Station.” Nevertheless, Stone’s initial residential design went on to win a silver medal at the 1937 exhibition of the New York Architectural League.4

The first of some two hundred names that would appear in Mepkin’s guest book over the next decade were those of Harry’s sister Elisabeth and her lawyer husband Maurice Moore. Beth had been skeptical of Clare at first. But during their January visit, she came to understand her brother’s attraction to a woman who seemed to excel without effort at everything. Aside from Clare’s obvious physical appeal, she was a mental match for Harry, challenging his opinions and stimulating him more than his own obsequious employees.5

“Claremont,” Mepkin Plantation, late 1930s (Illustration 24.1)

It soon became clear that the Luces did not have enough help to maintain multiple accommodations and 7,200 acres of land. Harry grumbled about local blacks preferring federal handouts to honest jobs. His wife, growing more conservative now that she had so much to conserve, sent a sarcastic wire to President Roosevelt, who had just addressed that same problem in his second inaugural.

Congratulations on your challenge to industry to reduce budget a billion by taking people off relief rolls. Rushing in to cooperate. Please tell me how to get seven able bodied Negroes with families for light farm and house work on plantation … Am willing to pay twenty percent over prevailing wage by yearly contract and provide Negroes with new living quarters. Have been unable to get any help in Charleston since purchase of plantation eight months ago owing to Congress’s relief legislation.6

Clare established a routine at Mepkin that would vary little over time. Her breakfast consisted of golden popovers and coffee with thick, yellow cream from the dairy, generally eaten in bed. Afterwards she indulged the habit, begun while working on The Women, which was to remain hers until death: to read and write, surrounded by pillows, books, and papers, for about three hours before becoming involved in the events of the day. Harry and her guests, meanwhile, might spend their morning hunting duck or fishing for bass and trout in the private lake. Lunch, announced by a gong, tended to be light: salads, shrimp in curry sauce, and rice dishes. Tea, made by Clare herself, was an exotic, frothy brew mixed in a blender with cloves and orange and lemon juice. For visiting children she would concoct chocolate, strawberry, and pineapple milk shakes.7

Later in the afternoon there was riding, or a four-hour buggy trip around the perimeters of the property. After cocktails, dinner was served at 7:30. It was a formal affair at a glass-topped table illuminated from below—unflattering to aging faces. Clare, still smooth-skinned at thirty-four, glowed impervious opposite Harry. She often dressed as a Southern belle, in full-skirted, turquoise taffeta, with short, puffed sleeves, pearls or lapis lazuli jewelry, and velvet bows in her hair. It was as though she saw Mepkin as a theatrical setting, with herself at center stage.8

In fact she was thinking about writing a new play with a Southern heroine, inspired by an encounter with George Cukor the year before. The director had been in Charleston scouting talent for the role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind. Clare saw comedy in his quest and decided to dramatize a similar search for an ingenue to play in the screen version of a Civil War novel. The idea was promising, but she would not realize it fully for another eighteen months.9

As the predictable result of having a beautiful, talented wife, a thriving publishing empire, and a lavish, peripatetic way of life, Harry was subjected to ridicule by Time’s principal competitor. A six-page New Yorker profile by Wolcott Gibbs censured him for allowing his latest magazine to feature nude Russian peasants, the mating habits of the black widow spider, and the adulterous gallivantings of Mrs. Wallis Simpson. Behind such “incomprehensible” lapses of taste loomed the “ambitious, gimlet-eyed, Baby Tycoon Henry Robinson Luce.”

Gibbs, a master parodist, imitated Time’s inverted sentence style, describing Harry as efficient, humorless, and chauvinistic.

Prone he to wave aside pleasantries … To ladies full of gentle misinformation he is brusque, contradictory, hostile; says that his only hobby is “conversing with somebody who knows something,” argues still that “names make news,” that he would not hesitate to print a scandal involving his best friend … Yale standards are still reflected in much of his conduct; in indiscriminate admiration for bustling success, in strong regard for conventional morality, in honest passion for accuracy; physically in conservative, baggy clothes, white shirts with buttoned-down collars, solid-color ties.

The author also noted that although Time Inc. employed highly educated women as fact checkers, its “anti-feminist policy” barred them from editorial advancement. Luce himself, growing ever “colder, more certain, more dignified” in his editorial pronouncements, was openly cultivating “the Great.” At thirty-eight he seemed to be already casting “a wistful eye on the White House.”10

Harry got page proofs of the article before publication. He had cooperated in good faith and was incensed that Time’s own bitingly satirical methods had been used against him. He complained to Harold Ross, The New Yorker’s editor, but the latter—perhaps because he himself had been unflatteringly profiled by Fortune—refused to change a word. Ross wrote to say that Luce periodicals had a reputation for “crassness in description, for cruelty and scandal-mongering and insult.” As for Harry, he was generally considered “mean,” even “scurrilous” on occasion, and was therefore “in a hell of a position to ask anything.”11

In early March, Harry, who went back and forth between Mepkin and New York as often as he could, brought his two sons down for a vacation. Henry Luce III, or “Hank,” was nearly twelve years old, and Peter Paul almost eight. They were not strangers to Clare, having spent two weeks cruising the New England coast with her the previous summer. Hank, intelligent and sensitive, found his stepmother “poised,” in contrast to his somewhat absentminded mother. He registered the “regal” way in which Clare told the maid to unpack his suitcase and how she liked monogrammed towels.12

Clare arranged so many activities at the plantation that both boys fell in love with it. They spent happy hours riding or hiking in longleaf pine groves and woods rich with cypress, magnolia, dogwood, and scarlet holly. In the afternoons, armed with .22 rifles, they hunted quail, dove, and wild turkey. At night they played monopoly or mah-jongg.13

Hank saw his father infrequently now and found him “stern and forbidding.” Yet he yearned to know him better.

I had a vague feeling of disappointment that Dad didn’t seem to be more in my life. I admired his enormous abilities, his judgments about world affairs, his anecdotes about meeting Presidents … I longed to please him, but when I’d report my little accomplishments it was very hard for him to compliment. He didn’t understand that things that were easy for him were a whole lot more difficult for others.14

His stepmother, selfish and manipulative as she could be with adults, had a sympathetic understanding of the fantasies of children and generously shared her time with them. They admired her inventiveness, curiosity, knowledge of unusual subjects, and wizardry at cards and jigsaw puzzles. Hank left Mepkin feeling that he had not one but two awe-inspiring parents, and diffidently signed the guest book “Henry Luce, Poor 3rd.”15

Having entertained Harry’s family, Clare prepared for a late March visit from Ann Austin, who for the past four months had been in Miami as usual with Joel Jacobs. Mother and daughter had not fully recaptured their old intimacy after Ann’s midlife difficulties. Perhaps to compensate, Ann kept in touch by writing gossipy accounts of her resort life. Clare was therefore aware of her masquerade as a Northern lady of means, energetically working the Florida gambling and party circuit. “No one here knows me … Or I them,” her mother confided. “So it’s all even.”16

Ann’s letters were like herself: disconnected, charming, and frank. She wrote with sensuous delight of putting on soft silks and pearls and sallying forth to dine in “smart diggins.” Invariably she outshone “the other old dowager buzzards … I fall over a Widner [sic], a Whitney or Vanderbilt on every hand.” Yet with fatalistic cheerfulness she acknowledged, “I may look young but each day … I move a day closer to the rendezvous with death.”17

She was unabashed about leaving her sedate husband in Connecticut while spending a third of the year in the sun with the easygoing Riggie. Except at the races, she saw little of Jacobs during the day. “At night I take people to dinner and he pays. Nice arrangement.”18

Though the months in Florida satisfied her obsession to be accepted socially, Ann envied her daughter’s intellectual life compared with her own mindless one. “The thing I resent is I made such bad use of youth. To Hell with muscle oil on the eyes wish I could get some for the brain.”19

Their reunion at the plantation was affectionate. (“Felt cared for … as if I had come home,” Ann recorded in her diary.) Inexplicably, however, she left after only two days. By the time Clare stopped off in Sound Beach to pick up little Ann a few weeks later, all daughterly warmth had vanished. “Oh God to think I would live to have one I’ve loved so dearly treat me like a stranger and walk out without the offer of help, or a kind word.”20

Back in town for the spring season, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Luce settled into a new apartment at the Waldorf Towers. Clare, as restless married as single, had wanted to leave the River House within months of renting it, and preparations for this latest move had been under way since January.

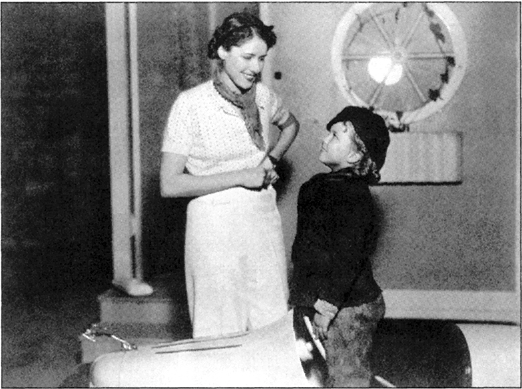

Ann Austin with her granddaughter, c. 1936 (Illustration 24.2)

The thirty-sixth-floor suite had a drawing room as large and sumptuous in its Art Deco appointments as any contemporary movie set. Mirror and glass flashed on walls and cocktail tables, and thick, pale carpets covered the floors. Heavy crystal ornaments, silver lighters, and expensive backgammon sets lay scattered about, and there were enough cut flowers to stock a small florist’s shop.21

Harry, left to his own choice, would have been content with something more modest, so long as it was near Rockefeller Center, where Time Inc. was soon to move. “Just like things convenient and sensible,” he had told Wolcott Gibbs. But he now had another person’s taste to consider. “Whatever furniture and houses we buy in the future will be my wife’s buying, not mine.”22

There was neither resentment nor reproof in this remark. Harry let Clare know he was willing to live wherever she chose, so long as each place pleased “your eyes and your fingers when you touch it.” But he reminded her that they had agreed not to give themselves social airs as “Luces the Magnificent.” No matter how wealthy they became, he wrote, “I take it we have decided we will not play any such role—certainly not in New York.” Surely all they needed was “an utterly charming pied-à-terre for a lady of great chique(?) and her husband,” coupled with a large Connecticut house and Mepkin as a winter retreat. So far as dignity was concerned, “we have all we can grow up to in our live-oaks.” The less they tried to impress “with foyers and footmen,” the better.23

But Clare, ever more enamored of luxury, intended to live like the movie star she had fantasized about becoming at age twelve. In the first three years of her marriage to Henry Luce, she would occupy no fewer than four apartments and five houses.

Her acute need to be perceived as stylish extended beyond herself and her surroundings to Harry. Gibbs’s derogatory statements in The New Yorker rankled. She suspected that her husband affected a sloppy appearance, despite the services of a valet. His trousers were often wrinkled, his shirts yellowing and frayed, his fedora battered, and his panama wilted. Sometimes he left for work in odd socks, or one black and one brown shoe. He would walk along the street, hat pulled low over his brow, staring at the pavement.24

Clare gave him a sleek platinum watch, but Harry ignored it in favor of an old-fashioned one of his father’s. The only other jewelry he wore, on the little finger of his right hand, was her wedding gift: a sapphire ring carved with the Luce family crest, already cracked from emphatic fist-pounding. She decided to take him sartorially in hand and steered him towards an exclusive tailor. Harry’s ill-cut suits gave way to elegant double-breasteds, which so enhanced his tall, lean frame that he was soon named one of the best-dressed men in America.25 Ironically, Clare had to wait a while longer to achieve similar distinction.

Having conquered Broadway with The Women, she now yielded to the blandishments of Hollywood. Norman Krasna, the writer-producer, asked her if she would like to adapt his story “Turnover” for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, at a salary of two thousand dollars a week. Clare replied that she would be crossing the country in May, en route to a Hawaii vacation, and would stop off in Los Angeles for consultations.26

Traveling in advance of Harry, she arrived in Southern California with little Ann on May 17, 1937. Almost immediately after checking into the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, she discovered that the movie industry was as interested in her looks as in her talent. Darryl Zanuck, vice president of Twentieth Century-Fox, invited her to take a screen test. This opened such intoxicating new vistas of fame and possible stardom that she felt she had to get Harry’s approval. He proudly wired her: “You are unforgettable … be afraid of nothing.”27

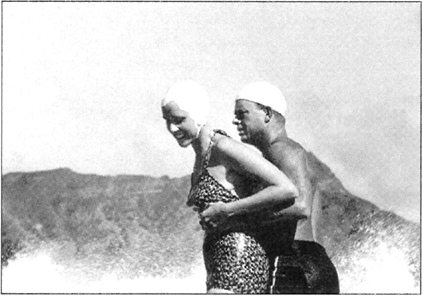

Clare in Hollywood with Shirley Temple, 1937 (Illustration 24.3)

Even though he had agreed to spend six weeks in Hawaii, Luce volunteered to stay with her in California for a further three if she won a movie role. This gesture of self-exile from his beloved magazines showed how starved he was for her company after the long Mepkin months. Should she now become a bicoastal creature of stage and screen, Harry must compromise his own career or see even less of her. In a post-departure letter, Clare had spoken ominously though vaguely of “renunciation” and “something having to go.” He wired back begging her to remember how blessed they already were and how careful they must be of their privileges. “Oh darling, we have got it—the chance to ride to glory.”28

Brooding and perplexed, Harry stopped over in Chicago for a dinner with local Time Inc. employees at the Blackstone Hotel. Ralph Ingersoll joined him in his room for a nightcap.

“I brought you here to tell you that when I go away tomorrow I may never be back,” Harry began in an almost angry voice. He said that love for his wife meant more to him than the company he had founded. “If I have to choose between them, I will choose Clare.”

After this outburst, he talked most of the night. Ingersoll sensed a tortured need to confess. There was “an unrealized component” in his marriage, Luce said, that had to be taken care of. Since Clare was all any man could desire, shortcomings in their relationship could only be blamed on him. His commitment to her was “imperfect and must be purified” or his life would amount to nothing. He should dedicate himself to “breaking through to total oneness” with her.

Harry admitted to previous failures in religion and creativity. His spiritual odyssey had been diverted towards a place in the pantheon of the powerful, and he had long since given up an ambition to write, realizing he would never be able “to make words sing.” Now he had found a new challenge in love. “I do not know how I am going to fulfill it, but only know that I have to … and to hell with Time Incorporated!”29

Like a priest searching for self-abnegation in God, he wanted to forge a holy bond with Clare.

In spite of Harry’s encouragement, and the efforts of the studio makeup department, Clare did no better in front of a movie camera now than she had in Heart of a Waif twenty-two years before. Nor did her story conferences with Norman Krasna go well. She had no sympathy for his female protagonist, who, trapped in a dead marriage, timidly asked for separation rather than divorce.30 After three days she lost interest and set sail on the SS Malola for Hawaii.

She had, however, so captivated Krasna that follow-up entreaties from him tracked her across the Pacific. He cabled a mock threat to kill himself over his inability to persuade her to do the script.31

To satisfy his wife’s need for sun and sea, as well as real estate, Harry undertook to find her a “little palace by the waters of Hawaii” that they could use for future vacations. While he went looking, she hired a handsome surfing instructor. No sooner had she mastered, with her usual quickness, the difficult art of manipulating a board in high seas, than she set herself to riding Waikiki’s notorious Queen breakers. “It’s a dangerous business,” she acknowledged. “If you miss the wave, you are likely to be ‘boiled’ in the surf, and dragged under.” Three or four people died each year in the attempt, but she did it twice. Afterwards she wondered why. “No one expected it of me, nothing was proved by it. But it was what I wanted to do.”32

Harry found no suitable Hawaiian “palace” on Oahu. Nor would he try again for another thirty years—by then, sadly, too late for him. In the meantime, the “total oneness” he sought with Clare failed to materialize. Apparently their airing of the “renunciation” question was inconclusive. Brought to the test, neither was prepared to give up anything. Both wanted to explore and experience all their own lives offered. Clare was alarmed by Harry’s expressed need to save his soul in her. She realized he had placed her on an impossibly high pedestal and now wanted to deify her. If she became a Madonna in his eyes, she feared with good reason that his Calvinistic conscience might put her sexually out of bounds.

Clare with surfing instructor, Waikiki, June 1937 (Illustration 24.4)

Intimates sensed their sudden unhappiness across thousands of miles. Bernard Baruch was struck by how “disconsolate” Clare sounded during a long-distance call, and David Boothe warned her of the erosive effects of marital fights. When they returned to New York in late July, Ralph Ingersoll looked carefully for signs of change in Harry—“some little hint that he had fulfilled himself”—but saw nothing. The Chicago soul-searching might never have happened. Clare was “briskly anecdotal” over dinner, saying that Harry had “almost mastered” the art of surfing, and that she was glad to be back in Manhattan after the insularity of Hawaii. In their suntanned complacency, the Luces seemed to Ingersoll “almost middle-aged.”33

In September 1937, The Women, still a Broadway hit, began a cross-country tour that would last a year and earn Clare an extra fortune. This was encouragement enough for her to start work on her satire of a Hollywood talent search. But first she had to see Ann settled at Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Virginia. Academically the girl was well prepared for the switch from Rosemary Hall, but emotionally it required painful adjustments. She would no longer be near her beloved grandmother and “Grumpy” Austin, not to mention “Uncle David” and the Manhattan movie jaunts they both enjoyed. Moreover, she must now associate and compete with girls from the most prominent families in the country.

At thirteen Ann Brokaw was over five feet, six inches tall and weighed about 120 pounds. She had a plain, angular face, fine skin, deep blue eyes, and thick chestnut hair. With adolescent sensitivity, she lamented her big nose and braced teeth, and contrasted her large-knuckled hands with Clare’s long, slender ones. Shy and melancholic, Ann knew she had “none of mother’s versatility or brains.”34

Having deposited her daughter at Foxcroft, Clare looked forward to a quiet literary sojourn at Mepkin. She was traveling there in mid-November when a special-delivery letter from Harry pursued her. He had written it on the second anniversary of their marriage but touchingly and cryptically dated it “Anno IV.” This signified that for him their real intimacy had begun at the Starlight Roof on December 9, 1934. There was no mention of their recent difficulties.

I am so excited about you that I am willing to forget these last 1,000 days—ready to lock them carefully in a great diamond-studded vault, to be brought out again and blissfully remembered only when the future comes to a dead stop and all my treasure is this great store of glittering days … Darling, darling, I love you. No woman who ever wore silk stockings pulled taut by strange devices to a girdle was ever so immaculate and such delicious flesh. And no matter how often I may observe your face, I shall never catch the lightning trick by which it shifts from brilliant theatrical beauty to the heart-shattering beauty of tender and companionable affection … Sure I love you for yourself—but that’s just the trouble, I don’t just happen to know it, that self of yours—I love it. It causes me infinite amusement, for example, but then, half the time, instead of just having a good laugh, my only desire is to throw my arms around you, to pick you off the floor, squeeze you and tell you you’re the sweetest bundle of baby God ever sent into a nursery. Or, perversely, in a great gathering of people, that same self of yours will make me bow inwardly with admiration.35

Little Ann came down to Mepkin for her Christmas vacation. Then, on New Year’s Day, 1938, Clare received a devastating message from her stepfather. Ann Austin, wintering as usual in Florida, had just been killed in a train-auto crash outside Miami. Joel Jacobs was comatose in Jackson Memorial Hospital with a fractured skull.36

Clare and Harry flew to Florida that night and met David Boothe there next morning. Police informed them that Ann had been driving her Buick sedan along South Dixie Highway at 6:45 P.M., on her way back to the Columbus Hotel from Tropical Park racetrack. At the Seventeenth Avenue railroad crossing, she appeared to have accelerated past several stationary vehicles, straight into the path of an oncoming train. Her action seemed almost deliberate, given that the whistling locomotive, traveling at about forty miles an hour, was in unobstructed view.

Both motorists had been thrown clear of the wreckage and lay immobile. A Catholic passerby knelt beside Ann and prayed for her, but by the time medical help came she had died from a broken back and internal ruptures. She was fifty-five years old.

Her left foot, severed at the ankle, was found some distance away. An onlooker recalled seeing an unidentified man pick up her purse and run off—in understandable haste, since the bag contained $27,000 worth of jewelry—two diamond and sapphire bracelets, a diamond and sapphire ring, and a diamond brooch. Ann had worn them the night before to a party and would have returned them to the hotel safe but for the absence of a clerk. Neither jewels nor thief were ever traced.

Joel Jacobs died on Monday evening, January 3. He was nearly seventy. By then Clare had arrived in New York with her mother’s body. Three days later family and friends gathered at Campbell Funeral Chapel on Broadway at Sixty-sixth Street. The service was conducted by the same clergyman who had married the Austins almost sixteen years before. Afterwards Ann’s body was cremated and her ashes taken to Strawberry Cemetery, not far from Mepkin.37

Clare and David were publicly quiet about their bereavement (the latter, enraged by Ann’s vampishness, had once expressed a private wish to “piss on Mother’s grave”). To one bystander Dr. Austin looked “like a soul in torment.” Ann Brokaw was inconsolable. She had probably spent more time with her namesake than with Clare, her father, her stepfather, her stepmother, and her half sister combined. “Dear Granny” had chosen her clothes, seen that she got a pretty haircut, housed and amused her on weekends away from school. “How I loved her,” she mourned in her diary. “I hope I shall grow to be much like she was.”38

Clare’s chief emotion over her mother’s premature death was guilt. She felt she had “let her down” during periods of illness and unhappiness. Since her divorce from George Brokaw, and her vow not to live “for anybody but myself from now on,” she had gradually—and now permanently—lost touch with the only person who could forgive whatever she might say or do.

“When one’s mother dies,” she wrote many years later, “one suddenly ceases to be a child. The structure of childhood … collapses, and in that hour adulthood, with all its responsibilities really begins.”39

Ann died intestate, leaving a $17,000 mortgage and only $2,250 in cash after inheritance taxes. Evidently the $500 a month that Joel Jacobs allowed her, supplemented in the last year by a further $200 from Clare, had not been enough to satisfy her extravagant habits and gambling debts.40

Ann Clare Austin

1882–1938 (Illustration 24.5)

Jacobs, in death, took unexpected revenge on his companion of twenty-three years, who had refused to marry him because of his race and religion. He had always led Ann and Dr. Austin to believe that he intended to bequeath them the bulk of his $5 million fortune. But in a will only two years old, he settled everything on immediate relatives, an attorney, and various Jewish philanthropies.41

One Connecticut obituary further upset the grieving doctor by stating that Ann had been “divorced” from her first husband. He placed a correction in the Greenwich Time, pointing out that the deceased was in fact “the widow of Mr. Boothe.” Thus he unwittingly perpetuated his wife’s most long-standing lie about her past.42

Ann Clare Austin’s diaries and letters reveal a romantic, spunky, but ultimately sad woman. In William Franklin Boothe she had found a sensual lover whose cerebral preoccupations, musical pursuits, and financial difficulties had driven her away after twelve years of wavering loyalty. In Dr. Austin she had married a fine, professional, but undemonstrative man, who cared nothing for the material things that mattered so much to her and who was aloof to the point of neglect.

Aging, she had come to see her dual existence with him in the North and Jacobs in the South as the only game available, and she had played it to the end. A few weeks before her death, she claimed to have found at last, in Miami, the freedom to be herself. And that self was, for all her flirtations with high society, fundamentally simple and joyous.

The social register never did anything for me but put my name on a lot of mailing lists. I’ve bobbed my hair—nothing more to let down—I’ve painted my toe nails a bright hue, burned my body a gorgeous tan, and am now enjoying the last gasp … I know just what I want out of life … my pearls large and my hips small.43