A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Another Republican casualty of the 1940 election was Clare’s stepfather, who lost his House seat by 1,100 votes. She speculated that the Democrats had won “by voting all the tombstones in the Catholic cemeteries” of Fairfield County.1 True or not, she was less surprised by Dr. Austin’s defeat than she had been by his marriage—twenty months after her mother’s death—to a private nurse exactly half his age.

Their union was to be short-lived. During the campaign an aide had noticed that the hitherto robust candidate appeared to be ill. “He was always taking his temperature, and drinking from a little bottle of whiskey.” One day, while he was making a speech at the Pickwick Arms, the doctor’s voice failed completely. It turned out he had cancer of the throat.2

Clare, meanwhile, continued to emerge as a political orator. In December, when President Roosevelt announced his Lend-Lease arrangement with Churchill, she returned to the lecture platform, sounding again her Willkie campaign theme that aid to Europe now might obviate the need for American troops later. She felt that she and Harry had been influential in the destroyer deal, and that the United States had acquired a strategic advantage by gaining in exchange bases in Newfoundland, Bermuda, and the Caribbean.

As isolationists like Charles Lindbergh continued to insist that the Nazis were exclusively Europe’s problem, those who preached intervention began warning that America itself might be an eventual target of the Third Reich. Clare stated this case forcefully when she said that the world was being swept to disaster by “the corrupting evils of pride-bloated state sovereignty, of hog-wild nationalism.”3

In acknowledgment of Clare Boothe Luce’s outspokenness and growing celebrity, The New Yorker published a two-part profile of her in January 1941 entitled “The Candor Kid.” It was written by Margaret Case Harriman—the same veteran journalist who, as Margaret Case Morgan, once complained that Clare Brokaw was politicizing Vanity Fair. Whether out of envy or revenge, Mrs. Harriman downplayed Clare’s current role as Cassandra, treating her mainly as a theatrical and social phenomenon.

The profile began with a satiric, Hans Christian Andersen-style account of Clare’s entry into the world.

Once upon a time, in a far country called Riverside Drive, a miracle child was born and her name was Clare Boothe. Over her cradle hovered so many good fairy godmothers that an SRO sign was soon put up at the foot of the crib and a couple of witches who had drifted along just for the hell of it had to fly away and come back for the Wednesday matinée. To the infant Clare, the first good fairy gave Beauty, the second Wealth, the third Talent, the fourth Industriousness, and the fifth Success.4

All were bestowed in triplicate so that the child was “more shiningly endowed than any other infant in the land.” But two curses pronounced by the witches complicated the baby’s long-term prospects. “I will give her Unpopularity, the distrust of her fellow men and women,” said one. “I have already given her Candor,” said the other, “which amounts to the same thing.”

Having interviewed a number of Clare’s friends and enemies, Mrs. Harriman felt qualified to comment on her objective way of looking at things.

People who know Clare Boothe well realize that the clear beauty of her face, the straight regard of her limpid eyes, and the light, high laughter with which she punctuates her conversation conceal nothing sinister. She is exactly what she seems to be—an amused, tolerant, unusually good-looking woman who has, perhaps, a blind spot in her perceptions. She writes vitriolic plays about vicious people not from any conviction that vice is wrong but because she honestly sees most people as bitches, two-timers, and phonies.

An unnamed source was quoted as remarking, “Most of us are used to the fact that a lot of people are louses, but Clare never fails to get a kick out of it.” Another repeated Dorothy Parker’s crack when Clare was said to be kind to her inferiors. “And where does she find them?”

For the most part Mrs. Harriman’s profile was a fairly accurate account of Clare’s life. What facts she had wrong were due mainly to her subject’s tendency to reinvent herself in interviews.5

Any pleasure Clare had from “The Candor Kid” was marred by a federal warrant claiming seven thousand dollars in back taxes from her brother. Having failed on Wall Street, then as manager of a cinema chain, and finally as an executive with Canadian Colonial Airways, David had now taken up flying. Thanks to Harry’s generosity, he had gone to the Ryan School of Aeronautics in Southern California, claiming to be thirty-six rather than almost thirty-nine. After training he hoped to become a pilot in any air force that would take him.

David had gone west swearing temperance, and Harry’s secretary warned him not to abuse his monthly seventy-five-dollar allowance. She understood that he was “on the wagon,” but even if he was not he must pay for drinks from his own cash, rather than add them to bills being paid by Mr. Luce.6

From San Diego, David wrote Harry ominously that “every other door is a saloon, gin mill or Palace de Joie.” He saw no harm in celebrating his first solo flight with “a little debauching.” Clare had not helped matters by giving him a car, and extra money for Christmas. In return he sent her the small span of gold wings he had just earned. “If you manage to outlive me,” he wrote, anxious to repossess the gift in death, “place said wings on my coffin.”7

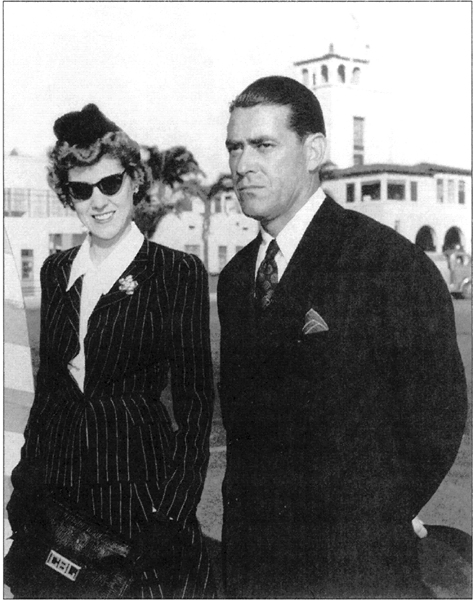

Clare visiting her brother at the Ryan School of Aeronautics, April 1941 (Illustration 33.1)

On January 22, Clare made a “Union Now” radio broadcast urging the English-speaking democracies to unite in the face of a common peril.

Morally, we are at war now … American planes are already bringing down German planes. American shells are landing on German objectives. All talk of non-belligerency, of technical neutrality, of loan-leasing, is just so much congressional persiflage … we have done, or are doing everything that becomes a great nation on the brink of war, except the one truly important thing: we have not stated our war aims.8

A few weeks later she spoke at the National Republican Club with Wendell Willkie, still the hope of the party. On a recent trip to London he had been treated like a movie star. This made Clare want to return to Europe again herself. Vague desire soon mutated into a daring plan to interview Hitler for Life. Telling John Billings only that she wanted to write about Germany, she applied for a visa.9

Harry, not to be overshadowed as an oracle, in the meantime adapted three of his speeches for a Life article entitled “The American Century”—a phrase that would be remembered long after the body text was forgotten.10 His essay, calling for the United States to assume its rightful place as a world force, was a plethora of platitudes, abstract nouns, and clichés, in spite of the best efforts of Billings and other editors. Luce asserted that Americans were unable to adapt “spiritually and practically” to the duty of world leadership. Their neglect of this duty brought dire global consequences. The remedy, as he saw it, was “to accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.”

Luce made only general suggestions as to how his grand design was to be implemented. America should begin by officially entering a war in which the Roosevelt Administration had already taken sides. Next it would be her duty, as the wealthiest participant, to guarantee universal freedom of the seas, to feed the destitute, and to share technical expertise. At the same time she should promote ideals of justice, equal opportunity, and self-reliance around the world.

Conservatives on the whole applauded “The American Century” when it appeared on February 17, 1941. But socialists and communists, looking to the postwar age for the liberation of the working man, felt it promoted “political tyranny and economic monopoly.” The Nation condemned Luce’s ideas as “lacking in a decent regard for the susceptibilities of the rest of mankind” and accused him of Anglo-Saxon imperialistic tendencies.11

On February 8, the German Embassy in Washington, smarting still from Clare’s barbs in Margin for Error, turned down her visa application.12 A few weeks later she sounded depressed in a speech billed as “Credo” and delivered at Pierson College, Yale.

“I believe,” she began, “that life is essentially tragic, but I believe this immemorial essential tragedy has a meaning. I believe that this tragedy can be endured by sane men, and that the meaning can be felt, comprehended, understood only in terms of religion … I believe that the status quo and the ante-status quo are both doomed.”

A strongly religious country, she went on, had the best chance of survival against such odds. Even so, its moral choices in an amoral world were “never between the desirable and the undesirable, but between the more or less undesirable.” Assuming the United States entered the war and helped defeat Hitler, victory would precipitate its own problems. “I believe that the horrors of the peace to come may be worse than the horrors of war, if we do not face the fact that the winning of a brave new world will be quite as hard and heartbreaking.”

Twenty years ahead of a young future president, she ended by eloquently cautioning that America’s political and economic systems were in danger of becoming corrupt. “I believe that our whole democratic conception of what the country owes the individual, of his rights and privileges, ceased to be valid when the last physical frontier was won, and that we will be forced by the iron veracities of events to put our emphasis more and more on what the individual owes society.”13

Clare had recovered her good humor when Orson Welles invited her and Harry to a private preview of his new movie, Citizen Kane. The director was nervously intrigued to see how Luce, the news tycoon, would react to the stinging portrait of his Hearst-like protagonist. Not only that but the picture began with an obvious parody of The March of Time. He need not have worried: his audience of two roared with laughter, if not quite in tandem. Welles recalled that Clare saw it as a joke, “and he had to because she did.”14

With her German trip aborted, Clare agreed to join Harry on a tour of the war-torn country in which he was born. Few Americans realized that millions of lives were being lost in an invasion half a world away from the nearer conflict in Europe. Harry’s idea was to write a report for Life while Clare took photographs. But she also saw the trip as a chance to collect material for a book to complement her last one. She might even call it “China in the Spring.”15