It is undefended riches which provoke war.

—GENERAL DOUGLAS MACARTHUR

Clare hardly recognized the young woman who flung herself into her arms when she landed in San Francisco from Hawaii on October 15, 1941. Ann Brokaw had grown from gawky schoolgirl to seventeen-year-old college student with amazing speed. Now in her first semester at Stanford, she was a slim five feet, seven inches tall, with wavy, reddish brown hair, large teeth, and a prominent freckled nose. Yet she was attractive enough to have featured recently in both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. A Pan Am engineer named Walton Wickett, who liked to watch seaplanes land at Treasure Island, noticed how warmly the two women greeted each other. He decided to try to meet the younger one.1

After answering press questions, Clare checked into the Mark Hopkins hotel and took her daughter to dinner in a Chinese restaurant. “Mummy was her usual beautiful, inspired and radiant self,” Ann wrote after hearing about her adventures, including her new friendship with a mysterious “German Baron.”2

Ann Clare Brokaw, 1941 (Illustration 36.1)

Ann always missed Clare but never realized how much she loved her until they reunited. “I don’t know what I should ever do without her.” The girl’s dependence was understandable, since her mother was everything she was not: sexually appealing, gregarious, witty, and creative. About all they had in common was an analytical power—though here again Clare’s intellect was superior—a passion for reading, and gift for self-expression.3 These traits were apparent in Ann at Foxcroft, where she had won several writing prizes and, in her final year, the prestigious editorship of Tally-ho magazine. But she excelled in music, to which Clare remained tone-deaf. Like her Grandfather Boothe, Ann played both piano and violin. She also sang soprano arias in a clear, natural voice of remarkable range.4

Clare had persuaded her to forgo a conventional début. Modern girls, she explained, were no longer “cloistered” and already enjoyed so much freedom that a formal presentation to society was unnecessary. No one ever took a débutante seriously if she wanted “to establish herself in a business or art.” Unspoken were more pertinent objections: a traditional début was enormously expensive as well as time consuming, and Clare had no inclination to spend vast sums on a celebration not centering on herself. She suggested that Ann just hold a few small dinner and theater parties.5

One of the young men Clare tried to pair Ann with was John Fitzgerald Kennedy, son of her own old flame Joe. But when the future President appeared to collect his date, he showed more interest in mother than in daughter. This happened so often when Ann brought boys home that she would grimace at any mention of Clare’s attractions and talents.6

Even though Ann was more or less grown up, Clare saw no reason to discontinue her thrifty habit of going through her clothes closets and handing down cast-off outfits. She asked her secretary, Isabel Hill, to ship an old mink to “a cheap furrier,” to dye and recut for Ann “so she could have it by Christmas.”7

Clare submitted her sprawling, seventy-three-page MacArthur manuscript to John Billings as soon as she reached New York. It was not well received. The editor felt, accurately, that she had “gushed” over her subject without revealing much about his character or his accomplishments, at least not in Manila. “Just a jumble of words … a mess!” She conceded that the piece was not “a peephole on the General”—given MacArthur’s evasiveness, it could hardly be that—but more like a political history of the country he was defending. “I have made an awful flop of this,” she wrote Harry. “Please help me.”8

Billings realized that his boss was “in a box between Clare’s ambitions at home and our criticisms at the office,” and suggested a solution. He would run another piece by Clare, about island hopping across the Pacific, in the next issue, under the title “Destiny Crosses the Dateline.” Meanwhile, Noel Busch, one of Life’s best editors, could make order out of the chaos of her profile for later publication.9

It was becoming apparent to professional eyes that Clare was turning into a facile, self-obsessed writer, too restless to amass the hard facts and ask the probing questions that journalism entails. Her playwright’s eye and ear were quick to pick out or invent colorful details, but being primarily imaginative and self-dramatizing, she did not care much if what she wrote about others was less than truthful.

Someone who was willing to point this out was her occasional Waldorf Towers neighbor David O. Selznick. That fall the producer dealt blows to her creative esteem much more devastating than those of her Life editors. Making full use of his powerful influence in Hollywood, she had already sold two stories to Paramount and was floating an idea for a screenplay about the Soong Sisters. Harry had also persuaded Selznick to be West Coast fundraiser for his pet cause, China Relief.

Clare’s latest proposal was to rework an introductory chapter to “China in the Spring” into an article about the movie colony. She blithely assumed “David” would like it, since it mentioned his charity work, to the disparagement of other producers, whom she accused of making “escapist” pictures while ignoring the reality of war in Europe and the Orient.

Selznick responded to her draft manuscript with vituperative outrage. “The story is filled with inaccuracies and untruths,” he wrote. “I think this is false, malicious, insincere, and ungrateful.” He was especially incensed by her setting him up as a “stooge” to her “superior discernment.

I don’t like the portrait of myself straight out of an old fashioned burlesque as having breakfast at one, without some explanation that I have been working the whole night previously. I don’t like a distortion and misquotation of my opinions, that were ventured in large part half seriously when we were both drunk. I don’t like the rather sad and disillusioning revelation that my guest had a reporter’s pencil and notebook, with the notes, incidentally, not being used until months later when the filling in was dependent upon memory of conversations over champagne.10

Selznick reminded her that he and his colleagues “have done a monumental job … in raising money for China Relief” and noted that she was now advertising herself as a platform speaker for the same cause. “Are you contributing everything you make on your lecture tour to China, or are you lecturing on China in order to make money that you personally pocket?” As for the adjective “escapist,” her own comedies hardly deserved anything better. If she cared so much about politically conscious scripts, why had she not written one of the caliber of All Quiet on the Western Front, or What Price Glory, instead of The Women and Kiss the Boys Good-bye?

Beyond his criticism of her article about Hollywood, Selznick unsparingly pointed out an aspect of Clare’s literary personality that he felt bordered on the pathological.

Forgive me if I say that seemingly you have some irresistible impulse to tear things down. I am fond enough of you, Clare, to wish that you could get some help, from friends if not from psychoanalysts in curing you of this habit. Believe me, it is going to boomerang on you increasingly … unless you will reduce the extent to which you persist in glorifying yourself at the expense of others.

He signed off after seven tightly typed pages, “With affection—which is certainly sometimes put to a very sore trial, David.”11

Nobody since Donald Freeman had so penetrated her amour propre. Mortified, she withdrew the piece and postponed her lecture tour. She sent Selznick a weak protest, saying that he could have given her a simple rap on the knuckles. He stingingly replied, “It is a bit inconsistent for the executioner to hate the axe.”12

Professional struggles and global uncertainty wore Clare down as winter approached. She complained of a recurring tropical fever and became contemptuous of the popular ambivalence regarding America’s world responsibilities. On Saturday, December 6, she assessed the country’s mood. “Nobody would be the slightest bit surprised if we went to war with Japan tomorrow, but if we did … everybody would fall flat on his face with astonishment.”13

Sunday dawned cold and crisp in Connecticut, yet by noon the sun was so warm it felt like Indian summer. As lunch guests began to arrive, a wind sprang up, whirling clouds across a lowering sky. Clare had invited a large party of diplomats and newsmen, as well as the Chinese philosopher Dr. Lin Yutang. In spite of her efforts to direct the table conversation towards Pacific affairs, it stubbornly focused on the European war.

During dessert a message was brought to Harry. He read it out. At about eight o’clock that morning, Honolulu time, Japanese bombers had attacked Hawaii and severely damaged the American fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor. Everybody jumped up and headed for telephones and the radio. Only Dr. Lin calmly finished his pudding. To him the Second World War had begun over four years before, when the Japanese attacked China.14

Harry left at once for New York. His Life staff had less than two hours to pull some morgue photographs of Honolulu, make new layouts, rewrite a seven-page lead, and rush the new issue to press in Chicago. Billings kept Clare’s cover story, “MacArthur of the Far East,” giving her one of the scoops of the century. Evidently she celebrated, because when she spoke that night as a guest on Jimmy Sheean’s weekly radio program, she struck at least one listener, the novelist Josephine Herbst, as being “slightly under the influence of liquor.” She gave “a mixed batter,” Herbst wrote in her diary, “of what everyone knows with the air of a spy returning from the front line, and as if the Japs had held off a day or so on purpose to reward her with this Hour of Hours.”15

Even as Clare drawled her Japanese conspiracy theories, diners in Manhattan restaurants looked quite serene, and skaters seemed blissfully unconcerned while careening around the ice rink in Rockefeller Center.16 But with the morning newspapers, the full horror of the surprise raid began to permeate America’s consciousness. The Honolulu casualty figures were staggering: over 2,000 servicemen killed outright or missing, and almost 1,200 wounded. Eighteen ships, including eight obsolete battleships, were in varying states of wreckage—only the Arizona had been irretrievably sunk—and 347 Navy planes lay destroyed or damaged. Luckily, two American carriers out to sea had escaped, along with dry docks and fuel dumps crucial to supplying the Far East theater.

Clare was distressed to hear that Japan had also hit Cavite harbor in the Philippines. Most of the newly imported B-17 bombers and P-40 fighter planes she had seen lined up at Clark Field had been obliterated. She worried particularly about Willoughby. Was he safe with MacArthur on Corregidor? Had his spies told him the raid was coming? Could the Islands be protected from infantry invasion if Admiral Hart carried out his hinted willingness to withdraw the Asiatic Squadron to safer waters? She longed to be back in Manila to ask these and other questions. But with the enemy already moving on Guam, Wake, Midway, and possibly the Aleutians, Clare knew she had little hope of crossing the Pacific as long as the war lasted.

What she did hope for was an opportunity, at this time of crisis, to capitalize on her own many talents. She was not sure yet what the best of them were, and of what use they might be. But she felt with rising spirits that both she and her country were coming into their own. Over thirty years later, speaking in Honolulu, she would nostalgically reminisce about this decisive moment in history. “No nation has ever been born great,” she said. “Greatness was thrust upon the United States by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. We were literally bombed into greatness.”17

The brazen suddenness of the Japanese assault, and the realization that the American mainland was now vulnerable, changed popular complacency overnight. Even Charles Lindbergh renounced isolationism on December 11, when Germany, honoring a pact with Japan, declared war on the United States. Clare’s own immediate reaction was to make herself an oracle of the master strategist Homer Lea.

Inspired by her talks with Willoughby about the tiny, forgotten hunchback, she spent several weeks in the New York Public Library researching Lea’s life and completed a thirty-page outline by the end of the year. She then invited Noel Busch to Mepkin to look it over. Billings rightly surmised that Busch would be expected to “pay” for her hospitality by recommending she submit the fruits of her scholarship to Life. When Clare telephoned to offer a two-part profile “at her usual rates,” the editor rejected it, saying Lea was merely “a footnote to history.”18

He should have known that Clare was a force not to be deterred. She sold the piece to Life’s nearest rival in circulation, The Saturday Evening Post. The hundred-dollar fee did not matter, she told Ann, since scholarly work gave her more pleasure than the most lucrative Hollywood scripts.19

Lavishly illustrated, “Ever Hear of Homer Lea?” appeared in two separate issues later that winter.20 With perfect timing, Clare simultaneously published an introduction to a reissue of Lea’s The Valor of Ignorance, elevating him to the rank of prophet.

Here was the prediction that Manila would be forced to surrender in three weeks. It was occupied by the Japs twenty-six days after the opening of hostilities. Here was the very picture of the convergent attack at right angles—the pincer movement—from Lingayen Gulf and Polillo Bight before which MacArthur’s troops fell back to entrench themselves on Bataan Peninsula … Here, above all, was a solemn warning against putting undue faith in “impregnable forts” in Manila Harbor (Corregidor, Il Caballo, El Fraile), unless they formed the base of a great fleet, equal to Japan’s, or were defended by a great mobile army.21

Not even this quadruple coup quelled Clare’s biographical ardor. She tried to interest both Irene Selznick’s father, Louis B. Mayer, and her husband in adapting Lea’s life to the screen, but without success.22

Stimulated by her work on Lea, and her recent exposure to the extreme right-wing views of Charles Willoughby, Clare spent New Year’s Day 1942 composing an extraordinary, twenty-nine-page, closely typed memorandum to Harry entitled “A Luce Forecast for a Luce Lifetime.” While much of the document showed her perspicacity and grasp of Realpolitik, it degenerated into paranoia, and worse. She began on a personal note.

We have had so many arguments about the war in the past three or four years. They have been a strain on our nervous systems and often on our affections. But once we were in the war we should have stopped them. Since the stake is America itself, we ought to have agreed on everything at last. But we didn’t and we don’t. Bitter arguments still flourish like an evil tangleweed in the otherwise happy garden of our affection, common admiration and respect. What makes these debilitating arguments so fruitless is that we argue most, not about past or current events upon which some decision might be found in books, but about The Shape of Things to come.

The word bitter had become habitual in her speeches and articles since their marriage underwent its great change. She was to use it six times in this polemic.

“I hope that we will both live to the year 1970: a quarter of a century more,” she wrote. “All I am going to do is to try to define a trend in political forces, based on geographical, political and racial facts, which, if not reversed in the next ten years, will lead inevitably to destruction of the U.S.A.” Given that the American Army had as recently as 1938 ranked nineteenth in numbers (below even Portugal), she considered it vital that the country now become and remain the world’s dominant force. This meant transforming its economic, spiritual, intellectual, and political wealth into overwhelming physical might, with an amply equipped, standing military—George Washington’s recommendation. The United States could no longer afford a foreign policy calculated to bring about defeat “at the hands of our enemies.”

Throughout the century, Clare observed, the most threatening nations had been those that had expanded territorially—Germany, Japan, and Russia—while the British and American empires had been declining in both size and “white” birthrates. The United States had consistently ignored this phenomenon, choosing its allies for ideological and commercial, rather than military or geographical, reasons. At the same time it had ignored evidence that the expansionist powers were arming themselves and annexing neighbors. In Europe, Americans had elected to support the weak consortium of Britain, France, Belgium, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Holland, “which resulted in Lend-Lease and the emasculation of the Neutrality Act.” In Asia the Roosevelt administration had illogically chosen China as an ally, while at the same time strengthening Japan with trade.

There are no words existent, nor will there be in history, for the sublime folly of choosing a country for your sentimental ally and at the same time supplying its immediate geographical and military enemy and yours with the essential materiel of warfare. This piece of gigantic stupidity will stand unchallenged in the annals of Democratic Foreign Policy.

As a result, Clare continued, disaster now loomed. A government “which leads a ‘great’ nation … into a two-ocean multiple front war, with a one-ocean navy and no armies to put in the field is a monstrosity, which if not traitorous, is surely imbecile.”

She felt that there was only “a fifty-fifty chance” of victory. If the Anglo-Saxon powers were defeated, then the future was too awful to contemplate. Even if they won, it would hardly be a triumph for democracy. The Allies might, with luck, negotiate peace in Europe “about 1945,” but it was likely to be on German terms. As for the Far East, she accurately predicted that Singapore, key to British defenses, would be lost to Nippon by March. The Dutch East Indies would fall soon after, and it would take “six years” to liberate the empire Japan had so defiantly acquired.

Win or lose, Germany, Japan, and China would continue to grow through the Fifties and Sixties, and beyond, because growth was “in their racial genes.” Weaker, darker nations, hitherto subject to domination, would simultaneously feel “stirrings of racial solidarity” and demand independence. “The day a ‘subject’ people becomes ‘free,’ the next day it allies itself with its former master’s enemies.” Hence, “we are doomed … to police the world.”

Clare’s peroration moved beyond reason to demagoguery. After expressing mock horror at “bloodthirsty” social theoreticians who suggested that the only way to restrict Nazi genes in future would be “to emasculate or slaughter all the males,” she found the idea tolerable herself. And not only in Germany, “for there is no other certain way to keep the Japs and the Russians down.” Ranting on, she wrote, “If we raze their towns and factories and manage to slaughter greater numbers of them than they do of us, we will have put a crimp for a number of years in their racial style.”

There remained the question of what to do about America’s biggest and most unpredictable ally. Lucid again, she set out an amazingly prescient scenario for the next two decades. After the war the United States would “sit down at a democratic peace table with the Russians,” only to endure “ten years of the ‘phoniest’ peace … we have ever known.” While Anglo-Saxons proceeded to consolidate their fragile commonwealths, “Demo-Russo Revolutions” would engulf Eastern Europe, and by the late 1950s “the Russian Century will have dawned.”

Her language was a deliberate jab at Harry’s notion of an American Century based on butter and Bibles. Clare’s own considerably less benign plan of action was, she frankly admitted, “totalitarian.” It was also fantastical, suggesting the corrosion of a personality denied the power that she felt born, if not qualified, to exercise. Abroad, the English-speaking peoples must combine, she insisted, into one super race. Germany, to contain Russia, should be granted Poland and “a hunk of the Ukraine,” not to mention control of the Danube basin and a few African colonies. Italy would get back Ethiopia. Scandinavia, in turn, would be cordoned off from Germany, and France restored to her prewar continental strength, keeping only Algeria overseas. Indochina would be given to the Chinese in exchange for U.S. naval bases. Last, “we send all immigrant Jews of the world … someplace … You pick where.”

Meanwhile she was quite prepared to abrogate the Four Freedoms at home.

I believe any means justify the patriotic end of helping our country to survive … If it should prove necessary in our lifetime and our children’s to scrap ‘our American way of life,’ our free enterprise system, our two-party system of government, and our constitution, to get it, I am for that, if only for the simple and logical reason that if we don’t get it, and if our enemies do, these things will be scrapped anyway.

She saw no other choice. “So I am a Fascist, I suppose.”23

One night at the plantation that winter, Clare had put on a green plaid housecoat, smothered cold cream on her face, and was ready for bed when a servant came in to announce the arrival of two young visitors from the Charleston Navy Yard. One of them was Ann’s escort of last summer, Ensign John Kennedy. “He looked very handsome,” Clare wrote Ann, “and he’s such a bright clever boy.” She passed on Jack’s news that a friend of his had thought her “swell” and “pretty.” Although Jack did not echo these opinions, Clare hinted that it might be worth cultivating his younger sister, Eunice, who had just gone to Stanford. “Do what you can to see that her first weeks are not too lonesome.”24

But Ann’s attentions were otherwise engaged. Walton Wickett, the young engineer who had been attracted to her at the Pan Am terminal, had succeeded in tracking her down. As luck would have it, he lived in Palo Alto, near the university, and soon contrived to meet her over hot chocolate at the Stanford Union. At twenty-seven Walton was ten years older, but he found Ann a mature match. He rated her at the top on his intelligence scale, admiring her extensive vocabulary and musical abilities, as well as her “lovely laugh.”25

Clare encouraged the friendship, so long as it made Ann happy. She did not know that Walton found Ann unusually introspective and not “a real part of the college.” This appealed to his sense of protectiveness, and he saw that she “liked being with somebody who was a little older.” Soon he had taken her home for supper with his parents. Afterwards, Mrs. Wickett remarked that Ann was a girl “with great outer poise, but great inner turmoil.”26

Rejuvenated as always by her stay at Mepkin, Clare was ready to fulfill an outstanding professional obligation to the Columbia Lecture Bureau. Her decision to postpone platform appearances after David Selznick’s onslaught had lost money for the agency. Fifteen speeches had been advertised in various cities, and Columbia wanted to recoup promotional expenses as well as 25 percent of an estimated $12,400 in fees.27 She now agreed to reschedule at least some of the engagements, and delivered the first lecture, “America Reorients Itself,” to an audience of 3,500 on January 9, at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C.

According to one attendee, who wrote an account of the event, many listeners had difficulty concentrating on Clare’s words, so effulgent was her stage personality. They were distracted by her svelte black dress, the American Beauty rose on her left breast, and her “golden halo of pompadoured soft waves.” Until Mrs. Luce reached fifty, the writer felt, people would probably pay more attention to her beauty than her brains, in spite of an oratorical “flair for the poetic-dramatic.” One of her most theatrical warnings, that Japan could well capture twenty-five American generals in the Philippines—“the biggest bag of brass hats in the history of any civilized nation”—had elicited a collective gasp.28

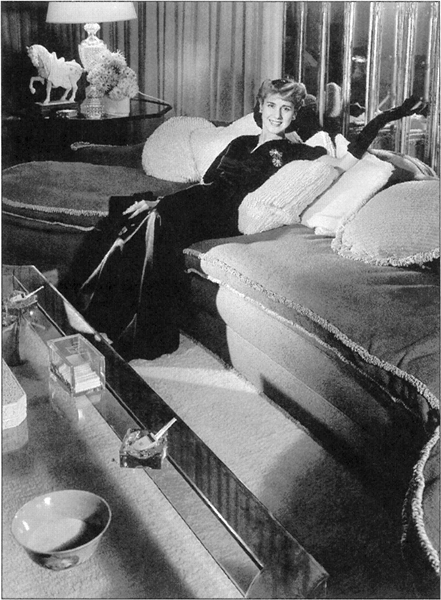

By now Clare was an expert self-promoter. Coinciding with her resumed lecture schedule, she published an article in Vogue entitled “What Price the Philippines?” In February the magazine would feature her in a glamorous portrait by Horst. She posed in the living room of The House on a sumptuous couch, wearing a black satin gown by Valentina, long black gloves, and jewelry by Verdura.29 Backed by mirrors, and surrounded by Art Deco ornaments, she gave off waves of elegance that were somewhat at odds with her role as global strategist.

Shortly after, it was announced that Clare Boothe was about to leave for the Middle and Far East on a two-month Life assignment. The peripatetic war correspondent had yet again orchestrated maximum publicity in advance of her reports from the danger zones.

Amid all the preoccupations of her luxurious and literary life, Clare found herself obsessing that same month over a yellow pottery fruit bowl. She noticed that it was missing from a shipment of furnishings and objets d’art sent to her by Dr. Austin, voiceless now from throat cancer and failing rapidly. Feigning ignorance of his true condition—she had not seen him for several years—she wished him well in recovering his “amazing energy and bounce.”30

Clare Boothe Luce

Photograph by Horst, 1941 (Illustration 36.2)

Most of the items from Driftway were emblems of Ann Austin’s social aspirations: an ornate tea service, a champagne cooler, crystal candlesticks, bejeweled evening bags, a thirteen-volume set of Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great, and a collection of silver toilette brushes that had always sat on the master bedroom dressing table. Clare was especially grateful for the last. She remembered Ann using them as far back as Memphis days. But she also wanted the yellow bowl, which she had bought for her mother as a girl, and she asked the doctor to look for it. “I will never forget how long it took me to save up the $12.”31

On January 26, Albert Elmer Austin died at the age of sixty-four. His stepdaughter, to whom he had brought respectability if not security, did not go to his funeral. She sent a fifty-dollar wreath and told the doctor’s former political aide, Al Morano, that although a snowstorm and sickness had kept her away, she had said a prayer at St. Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue.32

Morano was disappointed. He had been impressed by her speeches for Willkie and looked forward to telling her so. There was to be a congressional election in Fairfield County that year, and he had been optimistic, until Dr. Austin fell ill, that his former boss might recapture the seat for the Republican Party. “After the burial it hit me—I didn’t have a candidate.”

An idea occurred to him: why not approach Clare Luce?33