4

Power

How did people understand their place in the Late Antique world? How did political boundaries define their allegiances, and how did their identities change when those boundaries were redrawn? How is it even possible for us to stand outside some groups, looking out, while adopting the perspective of other groups, looking in? The questions are difficult to answer in any period. They are especially hard to tackle when the two groups we have our eyes trained on didn’t give much thought to engaging each other in neutral terms. Is it fair, for example, to stigmatize an entire population of Late Antique men and women as “uncultured,” “uncivilized,” or “barbaric” simply because they had the misfortune of being on the wrong side of our written sources?

The third century CE is an excellent starting point for this discussion, for it witnessed the rise of Sasanian Persia, which would parry with the Roman state both militarily and politically over the next three hundred years. Although the relationship between these two empires can be told as one of hostilities and conflict, as we saw in Chapter 2, this chapter digs beneath that rough exterior to find signs of more constructive communication. Both Roman and Sasanian monuments, rituals, artifacts, and texts reveal the nature of this quieter conversation unfolding in the background of so much political bluster. This chapter begins, then, not at the bottom of history but with the shifting power dynamics that affected the Mediterranean and broader world at the top.

4.1 Third‐Century Politics

For Rome in the third century CE, an empire that had dominated ancient Mediterranean life for more than three hundred years, the balance of power was about to change. Their new geopolitical neighbor was assembling that empire out of the pieces of old Parthia. It was an empire that would encompass modern Iran and, to its west, Iraq (the so‐called Fertile Crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers), as well as land to the north and west: portions of modern Armenia and territory in the southern regions of the Caucasus Mountains, between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. Founded in 226 CE when a member of the Sasanian family deposed the previous ruling dynasty, the Arsacids, the Sasanian Empire would remain a crucial power player in Late Antique history through the reign of its last king, 651 CE. Its capital was located at Ctesiphon, a suburb of modern Baghdad.

Romans had a long strategic interest in this region. They captured it once but ultimately decided not to control it. In the early second century CE, Emperor Trajan (r. 98–117) envisioned creating an official Roman province here, “Mesopotamia.” That political territory was carved from the land belonging to the Parthians, whom Trajan’s army had defeated. But the project never went forward. For much of the second and early third centuries, the Parthians continued to govern the land that lay just beyond the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Their presence there also kept several smaller, political entities in check. Territories in Armenia, Osrhoene (a kingdom to the northwest of Mesopotamia), and Hatra (a kingdom located south of Mosul, Iraq) were governed by local officials who allied with Parthia or Rome when, or if, they thought it convenient.

By the 160s CE – the time when the great philosopher‐emperor and Roman general Marcus Aurelius governed Rome – the territory along the Euphrates had been incorporated into the Roman state. Lands beyond the Tigris River now lay just within reach. The geopolitical situation would change again in the early third century, during the reign of the young Alexander Severus. When Alexander seized Osrhoene, it may have been the spark that set in motion the overthrow of the old ruling order within Parthia.

In 224, the Arsacid family was expelled from the capital in a coup led by the Sasanian leader Ardashir. Ardashir would be the first king of this new empire, soon to be called – for the first time in history – the land of “Iran.” Who were these people just beyond Rome’s borders?

4.2 Mithras and a Roman Fascination with the Mysteries of Persia

For centuries, Western historians have operated with an insidious case of “Orientalism.” The people and cultures of the east have been branded different, exotic, and unique. The “East,” as it provocatively came to be imagined, was the source of magic and mystery. Even in antiquity, Romans fell prey to these stereotypical ideas.

The Roman god Mithras, wildly popular during the second, third, and fourth centuries CE, was once thought by researchers to have come from Persian, or “Eastern,” origins. In art and sculpture, Romans always dressed Mithras in loose‐flowing clothes and fitted him with a floppy hat, the hackneyed image of an non‐Roman “Easterner” (Figure 4.1). Initiates into the private communities of Mithras worshippers were given a series of titles, which may have been awarded based on an individual’s level of financial contribution to the group. (The worship of Mithras itself was never granted the status of a publicly funded state cult.) Among these seven “grades,” one title was, appropriately, “the Persian.” Its symbol was a floppy, “Persian” hat and it is seen widely in the artwork of many community centers where Mithras’ worshippers met, called Mithraea (the Latin singular is Mithraeum). We will look more closely at an example of a Mithraeum, as well as consider the titles and artwork associated with the other “grades” of initiation, when we investigate what it meant to join such a group in later chapters.

Figure 4.1 A bronze plaque showing the Roman god Mithras slaying a bull. Depicted in wall paintings and sculptural reliefs, the scene was one of the most popular among Mithraic communities in the Late Antique Mediterranean. Mithras himself was worshipped across a wide geographic span, from the northern frontier cities of the Roman Empire, along the Rhine and Danube valleys, to the city of Rome itself and the territory of Roman Syria. This plaque, whose findspot is unfortunately not known, dates to the late second or early third century CE. It is currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Perls, 1997 (accession number: 1997.145.3). Dimensions: 14 × 11 5/8 × 1 3/4 in. (35.6 × 29.5 × 4.4 cm). Open‐access Met collection.

This evidence points us in a rather peculiar direction. By the third century CE, it would appear that many Romans were worshipping a Zoroastrian god even as their government was waging a war against the leaders of the Sasanian Empire. But can the evidence stand the weight of this interpretation? Recently, scholars have suggested not. In fact, the story of how Romans began to worship Mithras is much more complex – and quite eye‐opening. It began not with a specific act of cultural borrowing but with a more general Roman fascination for all things “Eastern.”

In Zoroastrian worship, the god “Mitra” was a a solar deity. His name, spelled “Mitra,” appears on inscriptions as early as the fifth century BCE. By the time of Alexander the Great and his successors, knowledge about this Persian sun god “Mitra” had spread to the world of the Hellenistic kings. There, one Hellenistic ruler – King Antiochus (r. c.69–c.31 BCE), ruler of the kingdom of Commagene, located in far eastern Asia Minor – took the Persian cult and transformed it in a way that carefully and cleverly advanced his own political agenda. The Hellenistic king erected statues dedicated to the god “Mithras” which depicted a panoply of stars and at least one symbol of a constellation, the Lion, which were meant to celebrate the king’s birthday. By mixing a Hellenistic fascination with astrology with the symbols of a Persian solar deity, King Antiochus – a descendent of both Hellenistic and Persian families – created a space where cooperation and shared tradition were uniquely built into the fabric of his kingdom.

Romans eventually conquered and replaced the Hellenistic kingdoms, but to many people of the Roman Empire, the worship of Mithras would always feature this important astrological component, inherited from the Hellenistic world. In short, just like the name of the god itself (“Mithras,” not “Mitra”), many aspects of Mithras worship did not come from Persia. That is why, as we have now seen, very little evidence exists to substantiate the claim that a Persian god was directly imported into Rome. The Roman god “Mithras,” rather, emerged organically as the creative result of many individuals – living at the borderlands of the Roman Empire – who wanted to capitalize on the appeal of a “foreign”‐sounding god to create a stronger community for themselves at home, even going so far as to dress up their private meetings with these aesthetically Persian veneers. None of these traits say anything about the origins of “Mithras,” but they do tell us quite a bit about the Romans. In the case of Mithras, they were allured by the “magic” and “mystery” of Persia.

So it will be, in Roman writers, for the people of Sasanian Persia themselves. Although Romans discuss aspects of the Sasanian Empire and how it came to power, ultimately, few writers were ever really interested in telling the history of its people from their own perspective. Romans used “Persian” culture to tell comforting tales about themselves. So where do we find evidence to understand the Sasanian Empire from the inside?

4.3 The Material Culture of Sasanian Persia

One answer is to look to archaeological evidence. King Ardashir (r. 224–239) and his transformational successor, King Sapur I (r. c.242–270), left behind a stunning record of monumental building that allows us to glimpse how the Sasanian rulers wanted people to view them. These pieces of material culture also allow us to explore how the Sasanian kings saw their own mandate to rule.

Some of the most important archaeological evidence comes from the cities of Behistun, Bishapur, and Naqsh‐i Rustam, all in modern Iran. All had been important places of political ritual for the leaders of the Achaemenid dynasty, the family of kings who had governed the last great Persian Empire in the fifth century BCE. The Achaemenid family had included such notable figures as Darius I, whose dramatic rise to power was narrated on a trilingual inscription on the face of a mountain at Behistun. The classical Greek historian Herodotus, who recounts the events that led Darius to attack Greece, knew this inscription and used it to draw his own biography of the Persian king. Behistun was a place rich with history and memory. It is no surprise the Sasanians wanted to build near there, too.

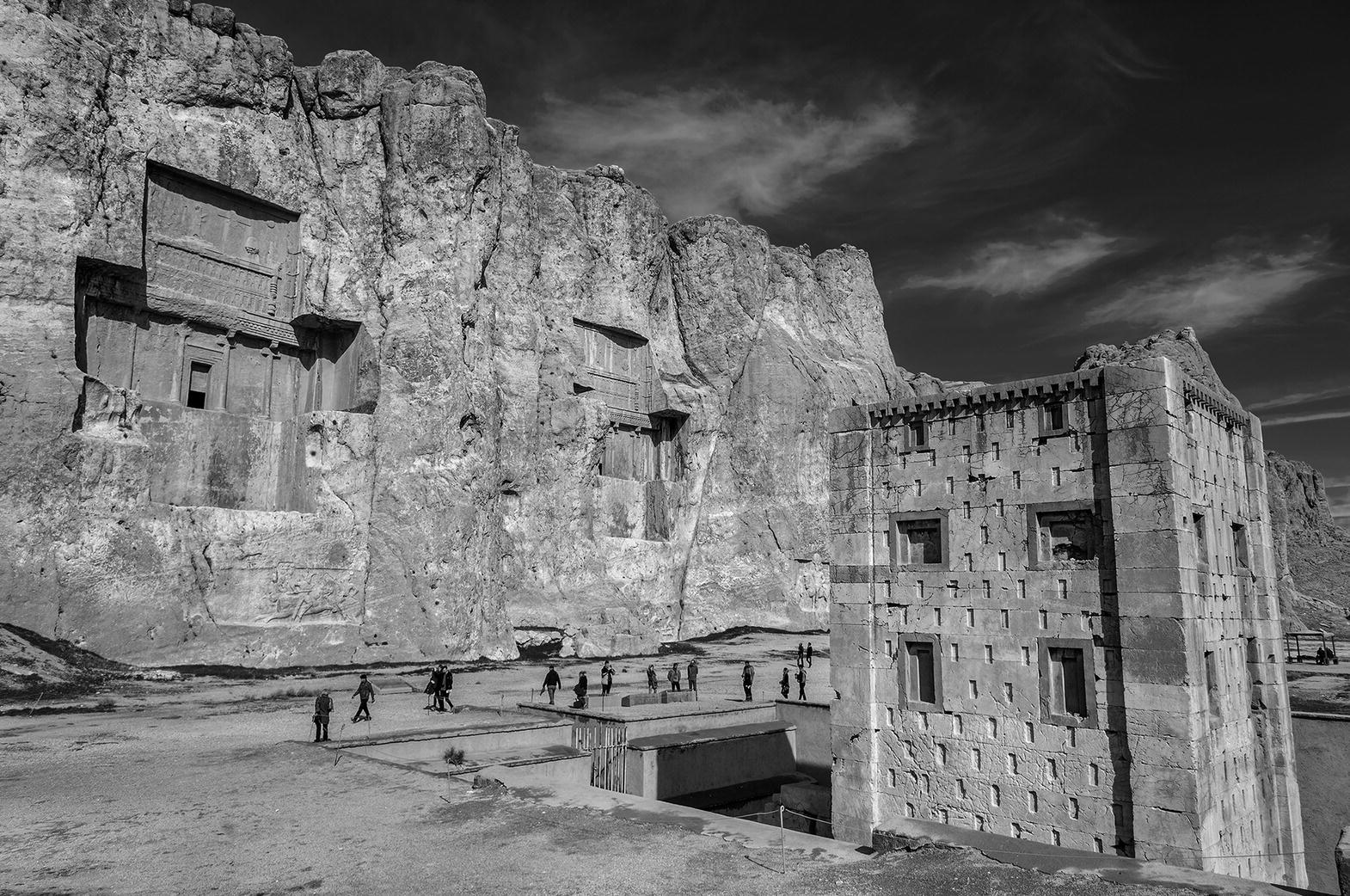

At Naqsh‐i Rustam, we see the Sasanian family articulating their political ideologies and cultural values. We should visit it and look at these remains more closely. The city itself is 12 kilometers, less than 8 miles, from the old Achaemenid capital at Persepolis, a city whose fields of tall columns still mark the place where King Darius and his son, Xerxes, ruled their empire. It was Xerxes himself who had famously battled Athens and Sparta for Persia’s stake in the Mediterranean until they were repelled and driven back to Asia Minor. Just as they had at Behistun, rather than relegate the powerful memory of this earlier age to oblivion, by letting these cities and monuments fall into further disrepair or by actively demolishing them, the first Sasanian rulers returned to these historic sites and referenced them by building around them.

At Naqsh‐i Rustam, several stunning reliefs have been cut into the cliff face that provide important historical information about Sasanian rulers. These sculptural reliefs depict Ardashir’s rise to power, the event which marked the establishment of the new Persian dynasty. In one scene, Ardashir receives his crown from the God of Light, Ahura Mazda (also known as Ohrmazd), the most important divinity to Zoroastrian worshippers (Figure 4.2). In another, Ardashir is shown trampling his enemies. The first person to be conquered is his rival, Ardawan IV, also known as Artabanus, the last of the Arsacid rulers.

Figure 4.2 Carved into the cliff face at Naqsh‐i Rustam, in modern Iran, is an image of the first Sasanian king, Ardashir of Persia (r. 224–242 CE). Ardashir, the founder of the Sasanid dynasty, is shown here on horseback, at left. He is meeting the Zoroastrian God of Light, Ahura Mazda, at right, who is depicted as his equal. By offering the new ruler a crown, Ahura Mazda invests the head of the Sasanian family with a symbol of divine authority. Zoroastrian values, beliefs, and worship were foundational to the Sasanian Empire. Third century CE.

Photo credit: Saman Tehrani, with permission.

King Ardashir’s victories are not limited to the human realm. The triumphant king is also shown celebrating a victory in the cosmic realm. In yet another relief, the artists have depicted King Ardashir vanquishing the Zoroastrian God of Evil, Ahriman. As a sign of thanks for his divinely inspired victory over his foes, King Ardashir is then shown touching his index finger to his mouth, a gesture of reverence. Behind him is an anonymous attendant who carries a fan or royal canopy.

What can we learn about the Sasanian king and his relationship to the divine forces of the Zoroastrian world from these monuments at Naqsh‐i Rustam? For one, we can see how the king presented himself on an equal plane with the gods. Battling the God of Evil, as if face‐to‐face with his spiritual enemy, Ardashir had crafted a subtle message that Persia’s new successes were a product of divine support. Ardashir’s diadem, in particular, awarded to him by Ahura Mazda, marks him as the divinely backed victor over the forces of evil. This ideology, intertwining the ruler’s successes with the Zoroastrian forces of Light (Good) and Darkness (Evil), would be promoted by all subsequent Sasanian kings. At the city of Bishapur, for example, Ardashir’s successor, Sapur I, would be shown in almost exactly the same fashion. Ahura Mazda gives King Sapur I his diadem, the symbol of his ruling power. Here, too, as in Naqsh‐i Rustam, the Sasanian king is seen defeating his adversaries and triumphing over spiritual forces.

One of the more thought‐provoking aspects of Sapur I’s monument at Bishapur is the man over whom the Persian king is claiming victory. The general depicted in the relief is the Roman emperor Gordian III (r. 238–244), an inexperienced ruler who led the Romans against the Sasanians in 244. In a traumatic loss for the Roman people, Gordian III never returned from battle.

4.4 Rome and Sasanian Persia in Conflict

The death of the Roman emperor, against the rising Sasanian power, was not something many Roman historians dwelled upon in their texts. In fact, if chance had preserved for us only our Latin and Greek texts, we would have a rather distorted view of what happened on the battlefield in 244 CE, when Gordian III died. Here is the report of the one Latin writer who describes the Roman march to war against Persia and the disastrous outcome of Gordian’s battle:

There was a severe earthquake in Gordian III’s reign, so severe that whole cities with all their inhabitants disappeared into the opening in the ground. Vast sacrifices were offered throughout the entire city and the entire world because of this. And Cordus [a historian] says that the Sibylline Books were consulted and everything that seemed ordered in them was done, whereupon the worldwide evil was stayed.

But after this earthquake, in the consulship of Praetextatus and Atticus, Gordian III opened the twin gates of Janus, which was a sign that war had been declared, and set out against the Persians with so much gold as easily to conquer them with either his regulars or his auxiliaries. He marched into Moesia. …

From there, he stormed through Syria to Antioch, which was then in Persian hands. There he fought and won repeated battles and drove out Shapur, the Persian King. After this Gordian recovered Artaxanses, Antioch, Carrhae, and Nisibis, all of which had been included in the Persian empire. Indeed, the Persian king had become so fearful of Emperor Gordian that … he evacuated cities and restored them unharmed to their citizens, nor did he injure their possessions in any way. (Writers of the Imperial History [Scriptores Historiae Augustae], “Lives of the Three Gordians,” LCL trans. by D. Magie [1924], 26.1–27.1)

The text, which is anonymous, comes from a collection of biographies of third‐century emperors known to later tradition as the Writers of the Imperial History (Scriptores Historiae Augustae in Latin, often abbreviated to SHA). The text continues by narrating Gordian III’s triumphs in Rome. There, like previous emperors, Gordian reported to the Senate and boasted of his victories, which he had achieved with the help of his father‐in‐law. The Senate itself decreed a victory parade, an important political ritual in Rome known as a triumphal procession. The writer of the Imperial History tells us that Gordian III’s parade was truly remarkable for featuring four elephants to show “that Gordian might have a Persian triumph in as much as he had succeeded in conquering the Persians.” If we were to end our reading here, Gordian III would enter the history books as a hero!

At this point, the biographer reports the upsetting news. While on a subsequent campaign, the head of the Roman emperor’s bodyguard, the praetorian prefect – a man named Philip who hailed from Roman Syria – conspired to arrange the emperor’s death. Philip spread rumors and slander among the soldiers, implying that Gordian III was too young to capably manage the empire. Soon, the praetorian prefect had convinced a group of soldiers to grant him and Gordian equal rank. A short while later, Philip arranged for the young emperor to be “carried out of sight, shouting in protest, where he was despoiled and slain.” As the writer of the Imperial History characterizes it, “At first [Philip’s] orders were delayed, but afterwards, it was done as Philip had bidden. And in this unholy and illegal manner, Philip became emperor” (SHA, “Lives of the Three Gordians,” 29.4, 30.8–9).

Philip’s cover‐up of the assassination was diabolically deceitful:

And now, that Philip might not seem to have obtained the imperial office by bloody means, he sent a letter to Rome saying that Gordian III had died of disease and that he, Philip, had been chosen emperor by all the soldiers. The Senate was naturally deceived in these matters about which it knew nothing, and so it gave Philip the imperial title, Augustus, and then voted to place Gordian III among the gods, bestowing on him the divine epithet Divus. (SHA, “Lives of the Three Gordians,” 31.2–3)

Is it fair to take this anonymous text at face value? The larger collection to which it belongs is a set of biographies of the rulers from the turbulent years of the third century CE. In it, the third‐century political and military world is beset by political killings, military defeats, and rapid turnover in the palace (Key Debates 4.1: Was There a “Third‐Century Crisis” in Roman History?). There are lots of reasons to be skeptical of the collection as a historical document, not the least of which is that the Imperial History was composed a hundred years after the events it describes – when Rome’s fortunes had rebounded and writers could begin to look back with some distance, mixing nostalgia for better times with hope about their present day.

There is a good reason to doubt whether Philip had ever really plotted to kill Gordian III, however. It comes from an inscription which was carved onto a monument at Naqsh‐i Rustam. After his many military victories, Sapur I, following the model of Darius, erected a trilingual victory inscription there. It was chiseled onto three sides of a rectangular tower, known as the Ka’ba‐i Zardusht, or the Ka’ba (or “Cube”) of Zoroaster (Exploring Culture 4.1: The People of “Iran”; Figure 4.3). It is an important third‐century document drafted by a Sasanian ruler and is a solid reminder that researchers need to work cautiously, especially when they depend on only one source to write their histories. For contrary to the way the Roman writer reports on Gordian III’s death, the Persian text makes no mention of the emperor dying at the hand of a treacherous praetorian guard. The text at Naqsh‐i Rustam says Gordian III died in battle. It says King Sapur I killed him.

Figure 4.3 The Sasanids were not the only ones who used the landscape at Naqsh‐i Rustam to promote their family’s authority and power. The relief sculpture of Ardashir, for example, is carved out of the same cliff where the mighty Persian kings Darius and Xerxes (fifth century BCE) were buried. Darius and Xerxes belonged to the Achaemenid family, the great Persian dynasty founded by King Cyrus in the sixth century BCE. His successors would rule for three hundred years and expand Persian territory westward to Egypt and Asia Minor and eastward to the Indus River in modern Pakistan. They were eventually overthrown by Alexander in the third century BCE. Six hundred years later, the Sasanids returned to the burial sites of these long‐gone cultural heroes to express their own hopes for a new empire. An inscription on the Ka’ba, a shrine for Zoroaster at Naqsh‐i Rustam, refers to the new Sasanian leaders as the kings of the people of “Iran.” It is one the earliest documented references to the name of the modern country.

Copyright © Leonid Andronov/Alamy Stock Photo.

Weighing the accounts, making a decision

What is a historian to do given that the Sasanian text so baldly contradicts the Roman one? How do we judge and weigh the validity of these sources? Who is right? In the end, does it really matter?

One school of thought would argue that Sapur I’s testimony is closer to the events he purports to describe and, hence, the more reliable testimony. Second, the writer of the Imperial History, looking back on the turbulent years of the third century, would have had a good reason to cover up the circumstances of Gordian’s death; Persia and Rome were locked in a fierce rivalry during this time, and it would not have helped the current Roman emperors’ diplomatic maneuvers with the Sasanian kings to popularize a story of Roman defeat. Lastly, there is the scandalous element of the Roman emperor himself dying at the hands of a foreigner. Because Romans were stubbornly proud of their military prowess and looked down on “barbarian” tribes, it is likely that the writer of the Imperial History changed the events that led to Gordian’s demise by blaming an upstart, conniving Roman soldier, Philip – in effect, framing the emperor’s murder as the result of an internal army squabble, not as the disastrous result of a foreign policy decision gone horribly wrong (Political Issues 4.1: Stigmas, Stereotypes, and the Uglier Side of Imperialism).

A second, alternative interpretation is also possible. Because Sapur’s inscription was intended to augment his own power and stature in Sasanian society, it may have deliberately manipulated the events of the battlefield to present the Sasanian king, not the Roman emperor, in the more flattering light. Whichever side of the story one chooses to believe, a broader vantage provides a clearer picture. The rise of Sasanian Persia was a trying time for third‐century Romans. Perhaps for that reason and for others, no continuous narrative of imperial politics exists for the middle of the third century CE. The monuments at Bishapur and Naqsh‐i Rustam offer vital perspective on the history of Sasanian–Roman relations during this tense time, seen from the outside and from the top‐down.

Admittedly, the picture that emerges from this perspective may look like one of constant clash and conflict. But, as we recall from our study of the origins of Mithras, not everything about Persia was necessarily seen as suspicious to Roman audiences. In the Sasanian Empire, too, many smaller artifacts attest to a level of dialogue that should cause us to question whether this was really a time of irrational, open hostility between two groups of people – or whether the conflict was limited to the officials in the palaces of the emperor of Rome and king of Iran (Working With Sources 4.1: A Cameo Glorifying the Sasanian King; Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 This piece of jewelry is a cameo, carved from sardonyx, a shiny black gemstone with bands of brownish red. On its face it depicts a battle between the Sasanian King Sapur I (r. c.242–270 CE) and the Roman Emperor Valerian. Cameo craftsmanship was a highly valued trade. Starting with a stone that contains a thin band of contrasting color (a stripe of white, as seen here), the artist would begin to shave away its exterior. When the two colors of the stone were dramatically exposed, a scene would be carved on its surface. This cameo, originally from Iran, is now in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France. Measurements: height 6.8 cm, width 10.3 cm (3.5 in. × 4.0 in.).

Photo credit: Erich Lessing/Art Resource.

To consider this matter in a slightly different way, we might try asking a slightly broader question: What did it mean to be or to identify as a Roman in the third‐century world? Was there one answer? Or were there many? If the latter, how did Romans grapple with so much diversity in a political system that was supposed to be unified and cohesive?

4.5 The Roman World of the Third Century CE

Empire‐wide citizenship is decreed

Looking back at the years before Sasanian Persia’s rise, we can quickly see that the Roman people and their leaders were already grappling with widespread social change at home. In 212 CE, Emperor Caracalla had announced that all free‐born residents of Rome’s territorial holdings – from the seasonally clammy isle of Britain to the perpetually dry sands and welcome oases of Egypt – would be granted Roman citizenship.

It was a momentous legal victory. For generations, many in the Roman world worked as second‐class residents of its empire. Although they may have held jobs that serviced the Roman army or provided food and goods to Roman politicians, families, and businessmen in their local towns, the Senate and People of Rome – the constitutional advisory bodies to the emperors – had never guaranteed any of these residents the same access to protections and rights that a real “Roman” had. Those protections were known as the ius Italicum, a Latin legal term roughly meaning “Italian rights,” and the ius Latinum, or “Latin rights.”

The idea of these rights had a long backstory. “Latin rights” had first become a pressing issue during the turbulent years of Rome’s growth as a republic. As cities throughout Italy began to demand access to the same kinds of laws and protections that citizens of Rome took for granted, they petitioned the Senate and People of Rome to share in the benefits of citizenship. By the early first century BCE, the cities of Italy would go to war to win these rights from Rome. Three hundred years later, by the time of Emperor Caracalla (r. 211–217 CE), “Italian rights” were bestowed on cities that had been founded with the approval of the Senate or the emperor, or awarded as a gift as a sign of the emperor’s graciousness. They could also be passed down generationally. These rights were a highly prized social ticket for residents of a Mediterranean city. They allowed one to live and work in Lepcis Magna (Roman Libya) or in Aquinicum (Roman Vienna) and feel that he belonged to the same class of people in Italy, the heart of the empire, or in its capital, the city of Rome. They also guaranteed one’s access to the codified protections of the Roman legal system.

By chance, the text of Caracalla’s announcement survives. A copy of it was written on a small piece of papyrus that was later thrown into an ancient trash dump in Roman Egypt, where it was later fished out. Today, this scrap is known as P. Giss. 40 because it belongs to the papyrus collection (“P.”) at the University of Giessen (“Giss.”) in Hesse, Germany. Although torn and tattered, which makes piecing the lines of text back together again a frustrating exercise, Giessen Papyrus no. 40 (P. Giss. 40) offers a ghostly record of Caracalla’s voice:

I grant … to all [free persons of the Roman] world the citizenship of the Romans … For it seems fair [that the masses not only] should bear all the burdens [of empire] but participate in the victory as well. [This my own] edict is to reveal the majesty of the Roman people. [For this majesty happens] to be superior to that of the other [nations]. (P. Giss. 40, trans. by F. M. Heichelheim, “The Text of the ‘Constitutio Antoniniana’ and the Three Other Decrees of the Emperor Caracalla Contained in Papyrus Gissensis 40,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology [1941], p. 12)

This piece of papyrus is also important because it preserves a story that speaks to Caracalla’s motivations. In the opening lines of the decree, Caracalla alludes to a recent assassination attempt. The emperor makes clear that his citizenship decree was a way of giving thanks to Rome’s divinities for saving him. Caracalla would not be the last third‐century emperor to appeal to the gods as part of a policy initiative for uniting the Roman Empire. The role that the Roman gods played as a kind of civic glue, keeping the diverse people of the Roman world together, is one that we will look again in the next chapter.

As for reaction to the news, only one writer – a man who wrote comfortably in ancient Greek – provides us any immediate comment on Caracalla’s decree. Cassius Dio (d. 235 CE) was a senator, a consul, and a provincial manager, and he was also not entirely convinced by the sincerity of the emperor’s piety. “This was the reason why [Caracalla] made all the people in his empire Roman citizens,” Cassius Dio says in his Roman History. “Nominally he was honoring them, but his real purpose was to increase his revenues by this means, inasmuch as aliens [non‐citizens] did not have to pay most of these taxes” (Roman History 78.9, LCL trans. by E. Cary [1927]).

Was the senator pulling back the curtain on the policy deliberations which had led to Caracalla’s announcement? Or was his cynicism a personal gripe, the result of his own cultivated contempt for Caracalla’s decision to knock down Rome’s borders and admit a whole host of “new Romans” to the empire? It would be helpful if we had more sources. As it stands, one has to start to wonder from what corners of Rome the notion of a third‐century “crisis” may have originated. For the new citizens of Rome, Caracalla’s decree marked the start of a new day, a new way of being Roman.

Rome’s birthday is celebrated, a saeculum is renewed

To think that third‐century Rome was a festive place – a place where cultural traditions continued, social customs were passed on, and the composition of the empire grew larger – cuts against the standard view of crisis. But there is every reason to look behind the curtains of gloom and doom, hanging in the palace, and see what was happening outside. The streets of Rome, even its most resplendent entertainment venues, were about to be filled with a celebration.

The faces of this new, changing Rome were everywhere, starting with Emperor Philip. In 248 CE, the soldier who would later be remembered for having murdered Gordian III would preside over the thousand‐year birthday of Rome. The city which had been founded by Romulus at the mythical moment of April 21, 753 BCE – the asylum city, the open city of debtors and creditors and murderers and magistrates (Plutarch, Life of Romulus 9.3) – was now run by a man, Philip, who had been raised in Roman Syria. Tradition, which is to say, the awkward customs of other history writers, would prefer that we label him as “Philip the Arab”; generations of history students have reduced Philip’s biography to this one ethnic attribute. But we should do better for the leader of 60 million people. Philip was Roman; he just happened to come from a corner of the Mediterranean most traditionalists in Italy couldn’t bring themselves to admit was part of their same world.

Like Caracalla, however, Philip, too, would depend upon the gods to unite the Roman people. And the thousandth‐year birthday party was a fitting time to give thanks for the empire’s resilience. Bronze coins that were circulated during Philip’s reign (r. 244–249 CE) show one of the most iconic symbols of Rome’s empire, the she‐wolf who had taken care to nurse the young Romulus and Remus after their birth. On the legends of these coins, a Latin text announced to everyone who picked them up that a new saeculum, or “divine age,” had been inaugurated.

The new saeculum would have given all residents of the empire enthusiastic reason for celebrating the gods, paying thanks to Rome’s long‐standing divine protection. Students approaching ancient history for the first time, however, may have some difficulty grasping the cultural significance of this word. Because it looks deceptively like the English word “secular,” it can lead aspiring historians to imagine that daily life in ancient Rome was similarly divided into the neat and tidy boxes which we use to organize our lives today: “religious” and “secular.”

Unfortunately, the Latin word saeculum did not carry that connotation. Romans had no word for distinguishing, or isolating, the “religious” elements of their daily life from the “secular” state. Both these concepts are borrowed from more recent periods of history, specifically the intellectual exploration of the Enlightenment, when thinkers and politicians began to devise conceptual frameworks for quarantining clergy from managing the government. By creating the idea of a “secular” space, one that was divorced from the influences of “religion,” Enlightenment thinkers engineered one of the most important social and cultural developments of the eighteenth century. Neither of these categories applies to Rome, to Late Antiquity, or to any period of pre‐modern history, however. And to write about the people who lived during this time as if they understood our modern terms is not recommended.

When Emperor Philip inaugurated the new saeculum for Rome, he was writing the next chapter in a divine story that stretched all the way back to the Etruscans – for whom the history of the world had been divided into discrete segments of time, or saecula (the Latin plural of saeculum). Only Etruscan priests knew the exact length of time that each saecula lasted, but the passing of one and the coming of the next marked a momentous occasion which had to be celebrated. Romans, who from the time of the earliest Republic had invited Etruscan priests into their governmental system, had continued this practice. It served to remind all Romans that the gods were truly looking out for the health of the Roman people and their empire. Caracalla, Philip, and still other third‐century emperors would all strike this optimistic note in their public policies, as we will see very clearly in our next chapter, which explores the role of worship in the Roman Empire.

New walls and city borders are constructed

As the Roman people took account of the Sasanian Empire on their eastern border, as they wrestled with the presence of “new Roman citizens” in their own streets and city centers, Rome and its emperors began to work to repair the snags and tears at the edges of society. Break‐away provinces were reincorporated. By the 280s CE, the Rule of Four would move into palaces throughout the empire. Throughout this time, the city of Rome matured.

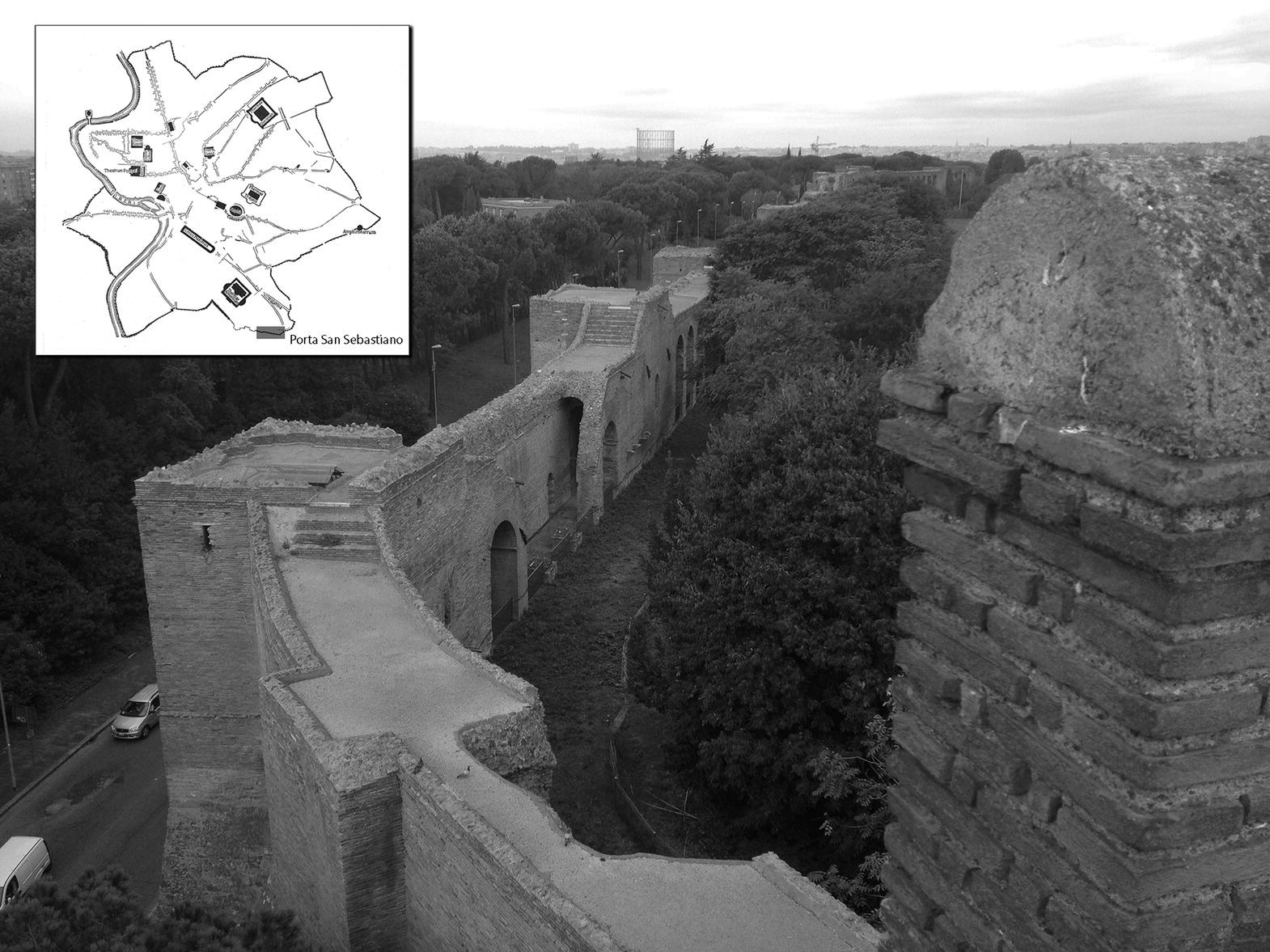

By 275 CE, the capital would be encircled by a towering new wall, both a practical defensive posture and a powerful statement about the city’s grandeur. (For material culture works in both these ways. It occupies a physical place in the landscape but it also shapes the world people live in.) In this way, the walls of Emperor Aurelian (r. 270–275 CE) would come to define the urban appearance of Rome for the next seventeen centuries (Figure 4.5). Designed to keep out raiders, at the same time they embraced parts of Rome – like the right bank of the Tiber and the tallest hill of Rome, the Janiculum – which had never been incorporated into the city. At the conclusion of the third century, then, even Rome’s city boundaries were changing, just as the boundaries of the empire were in flux around it. Aurelian’s walls are not a monument that can be easily made to disappear from history, either. Their durability and their lasting physical authority help explain why Rome would always carry the memories – even in the city’s darkest hours – of its once glorious empire.

Figure 4.5 In the late third century CE, the Roman Emperor Aurelian constructed a new brick‐and‐mortar wall for the city of Rome. The capital had long since outgrown its earlier defenses, constructed out of volcanic rock seven hundred years earlier during the city’s Republican period. Aurelian’s new wall would begin to redefine life in Rome and play a lasting role, in many urban forms, throughout the Middle Ages. This view of Rome faces to the west from the ramparts of the ancient gate now called the Porta San Sebastiano, leading to the church of St. Sebastian. With this new spectacular fortification, the neighborhoods in the distance, on the west bank of the Tiber, were included in Rome’s walls for the first time in the third century CE.

Photo credit: Author’s photograph, 2012.

If there was one hard‐and‐fast way to define what it meant to live within these borders, however, neither Emperors Caracalla, Philip, nor Aurelian had been able to articulate it. The best that some Roman writers seemed capable of mustering – if we consider the subtext to Cassius Dio’s discussion of the citizenship decree or, later, the fabricated tales told about Gordian’s death – was the highly debatable idea that being a real Roman simply meant not being or acting like “them,” whoever it is “they” actually were.

Summary

In the third century CE, another empire was formed at the eastern border of Rome’s. This Sasanian state would remain an important conversation partner for the Roman government and Roman people until it was conquered in 651 CE. Here, at sites in modern Iran like Naqsh‐i Rustam, Sasanian kings drew upon a wealth of Persian history, combining it with a divinely inspired understanding of their status as rulers, to evoke their strong vision for the Sasanian Empire. Kings like Sapur I used these sites to advertise their military victories over Rome’s emperors.

The Roman people themselves had long been fascinated by Persian culture and told themselves stories that the popular god Mithras, whom many Roman communities worshipped, had come from Persia. We also saw, however, that many of the traits and characteristics which Romans believed were “exotic” and “Persian” had been filtered through Hellenistic and Roman customs, transforming Mithras into something that tells us very little about the Persian people. Still, traces of dialogue between the two empires and their people can indeed be detected in the third century CE by looking at material evidence, which speaks to a level of artistry and craftsmanship that was crossing the newly erected political borders.

Lastly, we saw that, inside the borders of Rome during this same time, a simmering conversation about what it meant to be a Roman had led many emperors – Caracalla, Philip, and Aurelian – to take a more active role in promoting social and cultural unity among the people of the Roman provinces and the residents of the city of Rome itself.

Study Questions

- Who was Ardashir? What did he do, and why are his actions historically significant?

- Did the Roman and Persian people always live in conflict? How do you know?

- Evaluate the evidence for the death of the Roman Emperor Gordian III, using both Persian and Roman sources. How do you make sense of the conflicting reports?

- What do the policies and programs of Emperors Caracalla, Philip, and Aurelian tell you about Roman society in the third century CE?

Suggested Readings

- Matthew Canepa, The Two Eyes of the Earth: Art and Ritual of Kingship between Rome and Sasanian Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

- Hendrik Dey, The Aurelian Wall and the Refashioning of Imperial Rome, AD 271–855 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Beate Dignas and Engelbert Winter, Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbors and Rivals (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Jaś Elsner, Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire AD 100–450 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).