10

Economy

In the last chapter, four generations of Plousammon’s descendents told us about the lasting ties of family, home, and community in Roman Egypt. From the early fifth century CE, the time when Emperor Theodosius oversaw the establishment of Nicene Christianity throughout the empire, members of Plousammon’s family served in the Roman army, traveled outside the borders of the Egyptian town where they had grown up, and worked in the emperor’s palace. By the early sixth century CE, when the Roman Empire’s only capital was at Constantinople, the last known member of the family had settled back near home as a Christian priest. The circuitous tales of this one family, set against the competing lives of urban bishops and desert monks, exposed the complexities of life for citizens of Roman Egypt. Texts written on papyrus helped us piece this picture together, indicating the family’s movements over space and time.

Papyrus can also tell us about travel patterns that were a necessary part of people’s everyday work. The movements of one Roman army unit in Egypt offer an instructive example. According to papyrus fragments found at the “City of Sharped Nose Fish” (Oxyrhynchus), we know that one elite cavalry unit – called in Latin a vexillatio – was stationed there at the beginning of the fourth century before they were eventually divided up and sent on separate missions. This unit’s name was the Mauri. It is the unit to which Plousammon’s son, Flavius Taurinos, belonged, and around 339 CE, he and his fellow service members were given marching orders to disperse. One group was sent to Lykopolis; the other to Hermopolis. Because of the way Mauri soldiers show up on papyrus documents scattered throughout Egypt, not just in Oxyrhynchus, we can plot their rough itineraries over the span of two hundred years until roughly 539 CE when the records disappear.

The Mauri are the best documented unit in the empire’s Late Antique military. Between 339 and 539 CE, these men saw almost every corner of Roman Egypt. Reports indicate that, by the sixth century, they had even seen the first cataract of the Nile, where they would have spied the southern frontier cities of Syene and the island of Philae, site of an important Temple of Isis. (The first Nile cataract is one of six units of the river where the water turns into shallow rapids. Today, only one cataract is within the country of Egypt: at Aswan. The other five are further south, in modern Sudan.) Over the course of two hundred years, members of this elite unit also show up in Elephantine, near Syene; and at the western oasis in Lysis. (To learn more about the substance of these documents, see EBW [2007], p. 258.) By plotting this range of ancient cities on a map using geospatial tools, we can visualize how much mileage the Mauri were accruing (Figure 10.1). Taking data and translating it to a visual form shows that a soldier’s assignment in late Roman Egypt did not tie him to a specific city or region, even during peacetime. Over the course of a career or the course of a unit’s deployment, these men traveled considerably away from their home base in the “City of Sharped Nose Fish.”

Figure 10.1 Texts on papyrus are not only important as documents. They are important as objects, and where a scrap of papyrus was found can often give us fascinating information that might otherwise not be contained in the text itself. This map shows the distribution of papyrus records related to the Mauri units of the Roman army in Egypt, c.339–539 CE. As the data reveal, these soldiers were stationed far from the traditionally cosmopolitan cities of the Mediterranean coastline, suggesting that residents and villagers all throughout Late Antique Egypt knew the presence of Rome in their daily lives. By combining a detailed analysis of the documents with geospatial tools, historians can draw a more complex picture of Roman society and culture in Egypt, one that might not be immediately apparent when looking at just one or two scraps of evidence, especially outside Egypt’s more well‐known cities, like Alexandria. Open‐access mapping tools like the Ancient World Mapping Center, UNC‐Chapel Hill, make this task easier. Author’s map based on data from the Ancient World Mapping Center, UNC‐Chapel Hill.

This chapter looks at a few other people’s jobs, where their work took them, and at the entertaining ways they passed the time. What these individual stories will also help us describe is some sense of the nature of the economy before, during, and after the “vanishing” of Rome.

10.1 Egypt beyond Its Borders

There’s a good reason we’ve spent time looking at daily life on the ground in Roman Egypt in this and the previous chapter. “Egypt,” as a place, as an idea, held many Romans throughout the empire captive, even among people who had never disembarked at Alexandria or seen the Nile. This Roman fascination can be dated back as early as the first century BCE, the time when Augustus put an end to Hellenistic rule in Egypt and appropriated the land as his personal province. Egyptian‐style paintings, tombs built in the shape of pyramids, obelisks with hieroglyphics – all these began pouring into the Roman world and were devoured by Roman consumers.

Porphyry and the economy of marble

Specific locations in Egypt were especially prized for their luxury exports. That’s why, ever since the first and second centuries CE, the Roman government had taken imperial control of the quarries at Mt. Porphyrites, near modern Ghebel Dokhan. The stone mined from this mountain, porphyry, was a deep purple which, to Romans, evoked extravagance, power, and prestige. It appears in the floor of Rome’s Pantheon, built in the second century CE. By the third century CE, statues erected for members of the Rule of Four would be carved from it. In the fourth century, members of the imperial family would be buried in sarcophagi made of it. Constantine would set a porphyry column at the center of his Forum in Constantinople as the ultimate urban crown jewel.

Porphyry was not the only speciality stone used in construction, however. Since the first and second centuries CE, emperors controlled access to quarries in Roman Tunisia, where another uniquely colored marble called giallo antico was found. This yellowish stone, sometimes found in shades of orange and brown, also became one of the most prized elements in imperial buildings. Still others – like the purple‐veined though largely white marble from Roman Turkey known as pavonazzeto, or the dark green stone called serpentine from Sparta – contributed to a boom in Rome’s wide‐ranging marble economy. These materials were not just luxury construction goods. They played a role in conversations Romans had about their empire. Pavonazzeto had been used to depict statues of “barbarians” in Trajan’s Forum in Rome, for example. By using one of the finest imported marbles to depict “uncivilized,” conquered foreigners, the emperor was making a promise to his people about the greatness of the Roman military and the superiority of Roman culture.

By Diocletian’s time, the price of working in these marbles was astounding. And, thanks to the Edict of Maximum Prices, specifically, we have some relative sense of the cost involved. Serpentine from Sparta cost 250 denarii per foot. Giallo antico and pavonazzeto, 200 denarii per foot. Those planning to build in basic white would have been working on a slightly more modest budget. The maximum price for white marble, according to Diocletian’s Edict, was set at 75 denarii per foot. These prices would have created a two‐tiered system of construction costs, but that doesn’t mean the more expensive marbles were unavailable to moderately wealthy Roman home‐owners or patrons of synagogues or churches. In Late Antiquity, a popular floor and wall style, called opus sectile, used shaved pieces of colorful marble to create a pastiche design that, while certainly elegant, must have been a fraction of the cost of buying each stone by the foot (Key Debates 10.1: A Marble Burial Box with a Heroic Tale: Signs of a “Middle Class”?).

Egyptomania in Rome and Constantinople

Egypt exported more than its luxury purple stone. Papyrus was also popular, and the land’s cultural heritage – old sphinxes and obelisks from the age of the pharaohs – were some of the most visible artifacts in the empire’s capitals. At both Rome and Constantinople, the major race tracks of the cities were decorated with Egyptian pieces. Two of these artifacts were placed there in the fourth century. In the middle of the fourth century, Emperor Constantius ordered the erection of an Egyptian obelisk on the spine of the Circus Maximus. By the end of the fourth century, Emperor Theodosius had arranged for an obelisk to be brought to the hippodrome of Constantinople. These sites were two of the most popular entertainment venues of the Late Antique empire (Exploring Culture 10.1: The Grain Industry, Free Bread, and the Bakers at Ostia; Figure 10.2). The presence of Egypt in the center of each race track must have made every game day feel like a trip to another world, especially for men, women, and children who had never set foot in Egypt.

Figure 10.2 Founded in the third century BCE, Ostia was Rome’s harbor town, its connection to the Mediterranean, and a cosmopolitan city. Even as Rome built new shipping and warehouse infrastructure north of the city, at the site that would become Portus, Ostia remained a diverse town where the Late Antique elite lived alongside bakers, merchants, and other guilds of workmen and day‐laborers. Residents of Ostia knew how to enjoy themselves, too. The city was filled with taverns, many of which have been dated to the third century CE. These two rare artifacts also offer a glimpse at daily life. They are clay molds used for baking bread. Each is stamped with a design celebrating racing culture. The left shows a horseman and a four‐horse chariot, or quadriga (Ostia inventory number 3645). The right depicts a victorious racer on a chariot drawn by ten horses (Ostia inventory number 3530).

Courtesy of the National Italian Photographic Archive, ICCD (Photo E27259A).

10.2 The Arena and Racing Culture

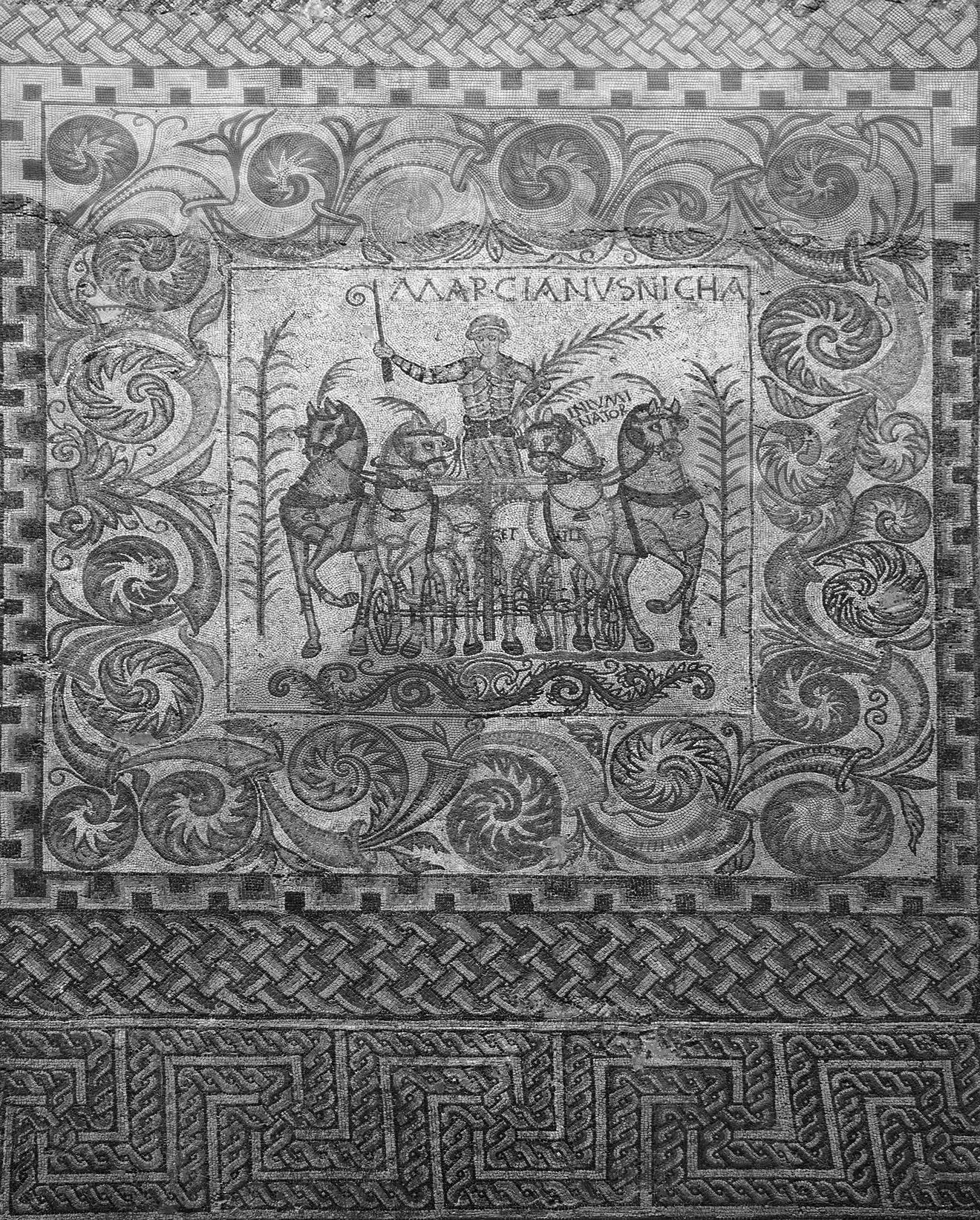

The broad appeal of gladiatorial matches, animal hunts, and chariot races vaulted many gladiators and race‐track drivers to the level of cultural superstars. Throughout the Mediterranean, in homes and taverns, archaeologists have found mosaic floors which depict episodes of hunting, boxing, and chariot racing. Oftentimes, the names of the athletes are set in stone along side these scenes. Sometimes, in chariot scenes, even horses are labeled. A mosaic from Emerita, the city of Mérida in Roman Spain (ancient Lusitania), for example, depicts one race‐driver, named “Marcianus,” with an exhortation to “Victory” (Nica, for the Greek Nikē). Marcianus commands a four‐horse chariot whose ace racer is also named: “Inluminator” (Figure 10.3).

Figure 10.3 During the early empire, the southern Iberian peninsula had been a mining region, where metals like gold, copper, and tin were extracted by slave labor. By the second century, Spanish olive oil had become a popular commodity offloaded at Rome’s wharves. During the “Rule of Four,” the provinces of the Iberian peninsula were reorganized into the diocese of Hispania. Mérida (ancient Emerita), in modern Spain, in the province of Lusitania, was one of its important cities. This expensive mosaic floor comes from a villa at Mérida and is a sign of the high‐level wealth that had been generated throughout the Iberian peninsula by Late Antiquity. It depicts a racer named Marcianus and his star horse, whose Latin name is also given: “Inluminator.” The palm leaf in the center and a Latin version of the word “Nikē” – the Greek word for “Victory” – imply that these two athletes were local heroes whose accomplishments were worthy of being set in stone. Second half of the fourth century CE. Now in the Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, Mérida (inventory number CE26389).

Photo credit: © David Keith Jones/Alamy Stock Photo.

This scene has been dated to the second half of the fourth century CE, and others like it have been found throughout the Iberian peninsula. On the one hand, these pieces of material culture show us the fame such men and their horses could acquire. They also tell us something about the economic world of racing culture more broadly. Although we know nothing more about people like Marcianus or their horses, vivid mosaics like the one in Mérida – commissioned for display in wealthy Roman homes – must have been counted among the owners’ most cherished conversation pieces. Perhaps they even worked to highlight their role as financial sponsors, or maybe they just spoke to their status as zealous fans of a particular team. (In Late Antiquity there were four: the Greens, Blues, Whites, and Reds.)

This culture spanned the entire Mediterranean; and, even after 476 CE, when places like Rome and Spain were cut off from the Roman Empire, it can still be seen in the Roman Empire centered around Constantinople. Around 500 CE, the emperor honored one of the most popular race drivers, named Porphyrius, with seven monuments originally displayed in the hippodrome. Today, only two of these monuments survive. On them, Porphyrius stands at the helm of his four‐horse chariot and receives a crown of victory from the goddess Tyche. The texts inscribed on the lost five monuments are also known from a Greek manuscript:

This Porphyrius was born in Africa but brought up in Constantinople. Victory crowned him by turns, and he wore the highest tokens of conquest on his head, from driving sometimes in one color and sometimes in another. For often he changed factions and often horses. Being sometimes first, sometimes last, and sometimes between the two, he overcame both all his partisans and all his adversaries.

(Greek Anthology 15.47, LCL trans. by W. Paton [1918])

This text tells the story of an athlete who was passionate about his sport but not so single‐minded about his team that he couldn’t recognize a good opportunity if and when it was offered to him. If there was a chance to win with another horse (or if the owners of another color paid him more), Porphyrius followed the money. Many of his adoring fans likely followed him.

10.3 Economic Realities, Third–Sixth Centuries CE

Porphyrius may not have cared where his money came from. He raced for whichever owner gave him a greater cut of the winnings, but other people were not so fortunate. They owned farms and worked the land, scraping by financially and sometimes at a season’s whim. Many rented land on large estates that belonged to wealthier landlords. The residents of the empire’s cities knew the comforts of a life built on consumption and trade. Here, in the empire’s more urban centers, lived people of varying degrees of wealth, and there was social and economic opportunity for those who were connected or took financial risks. Clearly the economy was built on the general concept of exchange, but can we say anything more specific about how it worked?

Economic historian Chris Wickham has been at the forefront of studying this pre‐modern system and has cautioned students and specialists about how difficult it is to generalize about it. Sometimes, a system of economic exchange – in which people trade goods, food, or money – is not necessarily driven by fixed rules. Wickham asks students to imagine the complexity of exchange in this way: “One can buy apples from a shop, or get a gift of apples from a friend, but one can also buy apples from a friend, perhaps at a special price for friends … Is this ‘really’ sale, or [is it a] gift‐exchange?” (Chris Wickham, Framing the Middle Ages [New York: Oxford University Press, 2007], p. 695). Wickham’s concern is that we should not expect the ancient evidence to conform to one set category. Parts of the ancient economy may have been built on values of consumerism and profit; others, on agricultural production and the redistribution of goods among people who needed them. Still others, on the allure of an old‐fashioned barter.

Some aspects of this system were assuredly greased by interpersonal connections. The fourth‐century writer Libanius, a lawyer in Antioch, was a teacher who was called upon to make this networked system work for his students. One of his pupils, Apringius, was planning to pursue further legal training in Berytus, Roman Beirut. He had asked Libanius to help him secure a position in town, based on Libanius’ professional connections. Libanius knew exactly whom to contact:

To Dominus: Thus, you inspire men of maturity to pursue occupations of the young. Apringius, our friend, after several trials before the bar (tribunal), has come to you to study law because it is from you alone that he can acquire knowledge … Try to shorten the time of his studies so that he can put his knowledge to practice. I will also entreat you insofar as tuition is concerned. He is a good man but poor and although he cannot give as much in payment now, he remembers favors.

(Libanius, Letter 1171, trans. by L. Hall, Roman Berytus: Beirut in Late Antiquity [London: Routledge, 2004], p. 209)

As Libanius’ letter on behalf of his impoverished student makes clear, the Roman economy could always be made to work in favor of those who knew the right people, regardless of how it worked for someone else (Political Issues 10.1: Cemetery Workers and a Guild Recruited for Mob Violence).

The two economic corridors of the state

Exchange, whether in money, favors, or a mixture of the two, was the central feature of this economy. As archaeological excavations show, objects made in one city or food harvested in another could travel considerable distances between the third through fifth centuries CE. At this stage, then, we should try to describe how and why the expectation of connectedness took root and what happened to it after the fifth century. The first two questions may seem basic to a student of the ancient Mediterranean; why wouldn’t Rome’s empire have been economically integrated? But here, too, historian Wickham offers a caveat:

It is not inevitable that the Mediterranean, or half the Mediterranean, should be as closely integrated as it was in 400 [CE]; it is not even “natural” given the similarity of resources in most Mediterranean regions. It is even less inevitable that interregional products should get substantially inland from coastlines and waterways … These processes were largely the products of the political and fiscal underpinnings of the Roman world‐system and, when that went away, so in the end did exchange.

(Wickham 2007, p. 718)

These are critical considerations to keep in mind when talking about what happened to the Mediterranean economy in the fifth through seventh centuries CE. The first step in the process of exploring the ancient economy, however, is determining what evidence to use. What do we have that is useful, and where do we find it?

By the early fourth century, the most important aspect of the Mediterranean economy was the emergence of two trade routes which pumped goods and money through the state like a twin set of arteries. These corridors were the two state‐managed sea passages that brought food from North Africa to Rome, in the west, and from Egypt to Constantinople, in the east. Both grain‐producing regions were heavily taxed, and as a result, government policies helped grow and sustain the trade between these provinces and the capitals.

Although the government did not itself determine what was traded, many enterprising merchants – in North Africa, for example – cleverly exploited both the state‐protected shipping routes and the availability of the steady stream of sailing ships to send their own goods to Rome. Fashionable ceramics from Tunisia, for example, could be packed on board in the left‐over cargo holds, offloaded at their destination, then sold in the Italian markets. It was a boon for everyone involved. Baked clay containers may be one of the most unassuming, ubiquitous class of artifacts discovered on archaeological sites, but for historians, these vessels hold more than the residues of olive oil and wine. Even in their broken pieces, they tell a story about the ancient economy.

The importance of ceramic evidence

Archaeologists find ceramics and sherds (not “shards,” a term which refers to glass) nearly everywhere. Marble could also travel great distances, but it was a luxury good. Ceramics were more widely used across a much more economically diverse set of the population.

Tableware, cookware, and kitchenware were made of clay and fired in a kiln. Once fired, these bowls and cups – although they could potentially be damaged in shipping, in the kitchen, or in a domestic fit of rage – were virtually indestructible. Because clay composition can be studied and traced scientifically, many ceramic production centers are known from the Mediterranean. Roman Tunisia was home to one of the most popular. Its kilns were famous from the fourth through eighth centuries CE for manufacturing vessels with a distinctive orangish‐red glaze, called “African Red Slip Ware.” During the third and fourth centuries CE, many North African merchants were filling the extra space in the state‐run grain shipments with extra pieces of African Red Slip Ware.

Ceramics help historians literally connect the dots of the Roman economy. By compiling the data for what kinds of ceramics have been found in which cities, specialists have been able to assemble profiles of the import–export trade across the Mediterranean. Between 300 and 500 CE, for example, most tableware found in the eastern Mediterranean is predominantly Late Roman C and D, a style of container manufactured on the island of Cyprus and in the Levant. African Red Slip Ware, by contrast, shows a greater distribution in cities and regions closer to Tunisia, like Roman Libya. This comparative evidence offers a helpful reminder that, even in the fourth‐century empire, when the state had two capitals and encompassed the entire Mediterranean basin, not everything about the economy was driven by the sweeping movements of trans‐regional trade (Wickham 2007, p. 707). Tableware in the Levant was supplied largely by an intra‐regional economy. Large parts of the Roman world were dominated by local economies.

The importance of the wooden legal texts from Vandal North Africa

A slightly different picture emerges from cities in the western Mediterranean. In 439 CE, when Vandals took control of Carthage, the cozy relationship between the state‐backed food trade and the enterprising merchants who had negotiated to have their own goods shipped in the extra space on board – a partnership which had lasted for two hundred years – was shut down. The Vandal political upheaval (Vandal Kingdom of North Africa and Sicily, r. 439–534 CE) did not halt all trade between North Africa and Italy, but the end of state‐sponsored grain shipments did disrupt a system that had benefited cities on both shores of the Mediterranean.

The situation for people living in North Africa during Vandal rule was also probably mixed. Farmers who had once been required to pay extravagant rent to their landlords, who, in turn, used the money to pay Rome’s taxes, now found themselves without the burden of an extra bill. As a result, more money in the Vandal period was likely pouring into the accounts of already wealthy citizens of North African cities. For those at the lowest end of the economic ladder, the situation does not seem to have improved. One extraordinarily rare set of documents, legal texts written on wood and found by chance in a storage jug, show us one farming family in Vandal North Africa that had hit hard times. These legal texts, written in Latin, are known as the Albertini Tablets, after the name of the French scholar, Eugène Albertini, who published the first transcription of them.

The Albertini Tablets call forth an intimate picture of the partnership that could exist between landlords and farmers in late fifth‐century CE Vandal North Africa. Many of the contracts specify that they came from the estate of Flavius Geminius Catullinus, which was being overseen by his family’s freedmen, at Tebessa in Roman Algeria. The names of two local peasants, Processanus and his wife Siddana, show up frequently in this collection. This couple owned the right to farm a small part of Flavius Geminius Catullinus’ large estate. And between 493 and 496 CE, Processanus and Siddana – “because [neither of them] knew how to read and write” (Albertini Tablets 13, line 33; Tablet 3, line 45) – worked with Catullinus and his freedmen overseers to sell back the rights to farm the land they rented.

In the course of these negotiations, the couple divested themselves of, among other crops and tools, a grove of fig trees and olive trees, and an olive press. All said and done, husband and wife eventually sold off almost six or seven plots of land. The final sum of money earned from these sales was one gold coin, or solidus. However much the people on the top rungs of the economic ladder may have been celebrating their freedom from the Roman tax system, the Albertini wooden tablets show that at least some people at the bottom were still “struggling to make ends meet” (Andrew Merrills and Richard Miles, The Vandals [Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2010], p. 160). The end of the Roman tax system, which had linked the societies and economies of North Africa and Italy in a strong bond, thus led to both a downturn and an upturn for the people of Vandal North Africa.

A hundred years later, the situation was thrown into tilt yet again. In 534 CE, the Roman Emperor Justinian recaptured North Africa from the Vandal government and reopened the long‐defunct state‐sponsored food routes. During Justinian’s reign, these ships no longer left Carthage for Italy, however, a land which the Roman Empire no longer controlled. They were setting sail towards an entirely new destination, the empire’s only capital, Constantinople. The newly recovered Roman control of North Africa, and the economic link between its cities and Constantinople, would last until the seventh century CE.

10.4 The Crypta Balbi Excavations, Rome: The Story of a Social Safety Net, Third Century–Sixth Century CE

What was happening to the city of Rome itself during this time? In 476 CE, the capital had been placed under the political management of Ostrogothic kings. Thanks to important new excavations from the city center, we can reconstruct the changing fortunes of the old capital and its people during this time. This evidence comes from the site of the “Crypta Balbi” in Rome’s lower Campus Martius.

Built in 13 BCE by a man from Roman Spain, Lucius Cornelius Balbus, the theater and crypt (or subterranean portico) which bear his name are fascinating sites in the history of the Late Antique city. The Crypta Balbi provides information that sheds light on the economy far beyond the limits of the city of Rome, too.

Visitors to the site sometimes don’t realize how unique it is. Roman archaeologists face a dilemma every time they begin an excavation. The amount of material that has accumulated, layer after layer over seasons and centuries, can make it difficult for researchers to decide which artifacts will be granted top billing in the final report and which ones will be relegated to fine print. In a modern capital like Rome, a city that has been inhabited for thousands of years, these decisions have acute consequences for our understanding of history. For the city of Michelangelo and the Renaissance popes sits on top of medieval limekilns and pilgrim churches, which, in turn, were built on top of Roman warehouses and ancient temples.

For much of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the lure of the layers of “classical Rome,” the period associated with big names like Julius Caesar, has meant that archaeologists made a choice to look for material that related to the first and second centuries CE, the period in which the Roman Empire expanded to its greatest geographical extent. Evidence from the in‐between times of history was often tossed aside during these campaigns or packed in a crate and sent to a storeroom. Sometimes, the circumstances of Late Antique discoveries were never recorded at all.

In the 1980s, archaeologists in Rome decided it was time to address this historical imbalance. During one of the largest excavations undertaken in the city since the time of Benito Mussolini in the early twentieth century, they made it a specific goal to find and record the entire stratigraphic story of one neighborhood: from antiquity to the present. These excavations took place on an ancient street a stone’s throw from where Julius Caesar had been murdered: the lower Campus Martius near the Theater of Pompey.

Ceramics from the Crypta Balbi excavations

For almost all Rome’s history, the lower Campus Martius had been located outside the walls of the city. It was not a suburban area, though. Rome’s first permanent theater, dedicated by Pompey, was located here, as were many temples vowed by victorious generals during the Republic. There was also a large open sanctuary, called the Porticus Minucia, where grain would be distributed to citizens who were fortunate to have a lottery ticket granting them a food supplement. By the first century CE, the area north of this distribution center would be occupied by Rome’s first Pantheon, an audience chamber built to honor Augustus.

Cornelius Balbus contributed to this development (Figure 10.4). In 13 BCE, he added a second theater and the subterranean portico which bore his name. Less than a century later, a fire would devastate much of the surrounding area (c.80 CE), but Balbus’ projects remained an integral part of the Campus Martius into the third century CE (Working With Sources 10.1: Coins as Evidence for Ancient Inflation?).

Figure 10.4 When the Emperor Aurelian paid for the construction of Rome’s new walls at the end of the third century CE, some neighborhoods which had once been outside the city’s boundaries were suddenly located within it. The Campus Martius, or Field of Mars, was one such region. In 13 BCE, Cornelius Balbus, whose father had been born on the Iberian peninsula, had dedicated a theater here to honor the rise of Augustus. This plan of the lower Campus Martius shows the urban area around Balbus’ theater in Late Antiquity. During the empire, citizens received their state‐sponsored grain distribution at the nearby Porticus Minucia; it fell out of use in the late third century CE and, by the fifth century, had become a Christian guesthouse (called a xenodochium) and a church. Plan by D. Manacorda, Crypta Balbi, Archeologia e Storia di un Paesaggio Urbano (Milan: Electa, 2001), p. 44. Used with the permission of D. Manacorda, with author’s modifications.

The excavations of the 1980s have been particularly beneficial in helping scholars reconstruct the history of the site beyond the third century. During those campaigns buckets and eventually crates of ceramic material came to light that have shed light on our understanding of the Late Antique economy. By the end of the excavations, 100,000 sherds had been collected that illustrate the nature of the goods coming into Rome between the third and sixth centuries CE.

Ceramic specialists identified 47 percent of the collected material as having once belonged to amphorae, or shipping containers for liquid like oil or wine (singular, amphora). Of these amphorae sherds, nearly half of the material was classified as African Red Slip Ware, coming from North Africa. One fifth of the amphorae transport containers were imported from the eastern Mediterranean. A tenth of the amphorae had been shipped from southern Italy. The source of the remaining vessels could not be identified.

Additional data from Rome’s harbor town, Ostia, compiled from the study of nearly 4,000 sherds unearthed during excavations in the late 1990s and 2000s, confirms the general outlines of this picture in Rome. It also allows us to see the historical picture with a little more specificity. Transport vessels for wine and olive oil are particularly well attested at Ostia. Between 280 and 350 CE, Ostia was importing approximately 64 percent of its wine from eastern Mediterranean markets. These products came from the Aegean Sea and Black Sea. By contrast, about half of Ostia’s olive oil was being imported from North Africa during this same time. If we look at the evidence that can be accurately dated to the period between 350 and 475 CE – the time period just before Ostrogothic rule was established in the city of Rome – this robust data line shows surprisingly little signs of falling. Wine imports into Rome during this period are actually more geographically diverse than in earlier periods. About 55 percent of the imported wine was originating in the Levant.

As for olive oil amphorae, ceramics from Ostia suggest nearly 91 percent of the old harbor town’s supplies were coming from North Africa. (For an in‐depth look at these numbers, including the significant sample sizes, see the report by ceramics specialist Archer Martin, “Imports at Ostia in the Imperial Period and Late Antiquity: Evidence from the DAI‐AAR [German Archaeological Institute‐American Academy in Rome] Excavations,” in The Maritime World of Ancient Rome, ed. by R. Hohlfelder [Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008], pp. 105–118.)

When the material from Ostia and the Crypta Balbi are taken together, then, a snapshot of the Late Antique economy does begin to develop.

While other cities throughout the Italian peninsula may have seen a drop‐off in goods from North Africa with the end of the imperial food deliveries, Rome, at least, maintained a thriving import economy between the third and late fifth centuries CE. In other words, we might say that underlying economic features of the capital of Ostrogothic Italy proved quite resilient, even during a change in government from empire to kings.

Two final details from the Crypta Balbi excavations

There are two other features of the Crypta Balbi neighborhood which are significant. One relates to the changing patterns of Rome’s urban history, the other to events in contemporary Constantinople.

Food handouts would cease at the Crypta Balbi sometime at the end of the third century, as portions of the Porticus Minucia were abandoned. Over time, this large open public space would be gradually raised by rubble. And by the sixth century CE, a xenodochium, or Christian hostel, had been built on the site of the former food distribution center. We know because a Latin inscription records the act of a late fifth‐century Roman aristocrat, Anicius Faustus, who paid to have the space transformed back “into its earlier use” (CIL 6.1676).

Anicius Faustus was a member of one of the wealthiest families in Rome, the Anicii. Later bishops of Rome, like Gregory I, make reference to a “guesthouse of the Anicii family” as a famous center of Christian philanthropy and care for the urban poor (Gregory, Letters 9.8). This “social service” institution is also mentioned in the Latin biography of the ninth‐century Pope Leo III (Liber Pontificalis [Book of the Popes] 98.80) as being located near the monastery of Saint Lucia, which was built inside the Porticus Minucia. All this evidence suggests that, even as state‐sponsored food distribution was stopped with the Vandal occupation of North Africa, wealthy Romans picked up the reigns of this long‐standing city tradition. Anicius Faustus seems to have reinstituted it on the same site – this time, as his own private gift.

The last important detail to emerge from the Crypta Balbi pertains to life not Rome but in fourth‐century Constantinople. On May 18, 198 CE – according to two Latin inscriptions that have been known from Rome since the sixteenth century – the guild in charge of measuring grain at the Porticus Minucia was honored with statues of the twin gods Castor and Pollux (CIL 6.85a–b). The date for this dedication was not chosen at random; it was the day in which the sun passes into Gemini, the constellation named for “the divine twins.” The two statues thus functioned as a generous acknowledgment to the work of the grain measurers but also called upon Rome’s divine protectors of seafaring to ensure the safe arrival of food in the future.

A century and a half later, after the Christian emperor Constantine founded his new city on the Bosporus, workers in the second capital were still following this Roman model. On May 18, 332 CE, the people of Constantine’s new city celebrated the festival of the Annonae Natalis, which honored the successful delivery of food from Egypt (Chronicon Paschale at 332 CE) – the exact same day Romans gave thanks to Castor and Pollux for ensuring food delivery in Italy. That holiday correspondence tells us, once again, that some customs and festivals in fourth‐century Constantinople were not immediately different than the ones celebrated in Rome itself. Traditions could be imported, too.

Summary

Studying the economy demands careful attention to assumptions, working definitions, and method. During the period in which the Roman Empire had two capitals, the main economic corridors were the state‐sponsored food delivery routes that linked North Africa and Rome, in the west, and Egypt and Constantinople, in the east. Luxury goods, like marble, played an important role in the economy. But smaller, more everyday objects, like ceramics, give economic historians more useful data for reconstructing imports, exports, and trade across the Mediterranean.

As this data reveals, many merchants, particularly those in North Africa, capitalized on the state grain shipments to ship their wares to Italy and cities far beyond Roman Tunisia and Algeria. Apart from the continued presence of African Red Slip Ware in Rome, however – seen in the Crypta Balbi excavations and at Ostia – Italian demand for African Red Slip Ware withers in the fifth century CE. From this phenomenon, economic historians like Chris Wickham have deduced that intra‐regional trade, not trans‐regional shipping, was a more important, more resilient feature of the Roman economy than we sometimes assume. Thus, although goods like marble could travel great distances, long‐distance trade eventually became less prevalent in the late fifth‐century western Mediterranean when the Roman food system – which had long sustained these twin shipping routes – was finally shut down. In the eastern Mediterranean, the greater number of sea routes for bringing food from Egypt to Constantinople sustained the Roman Empire in the east for two more centuries up until its loss of Egypt to Arab armies in 641 CE.

Study Questions

- Identify the following marble types by their color and geographic origin: giallo antico, porphyry, serpentine.

- What evidence do historians use to estimate the cost of marble construction projects?

- Why are ceramics such an important body of evidence for archaeologists and historians?

- The Crypta Balbi excavations present a slice of daily life in Rome before and after 476 CE, when Christian emperors were replaced by Christian kings. How did society and culture change during this transition?

Suggested Readings

- Alan Cameron, Circus Factions: Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976).

- Leslie Dossey, Peasant and Empire in Christian North Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

- Ine Jacobs (ed.), Production and Prosperity in the Theodosian Period (Leuven: Peeters, 2014).

- Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).