14

A Choice of Directions

War arrived with the coming of the seventh century CE. Two Arab families – the Jafnids and the Nasrids – would each watch as their respective allies, Rome and Persia, clashed over access to trade routes between the far east and the Mediterranean. This conflict, although perhaps only tangentially related to the daily life of the Jafnid and Nasrid families on the Arabian peninsula, would, nevertheless, come to affect Late Antique history in a crucial way.

The use of client kings, by Rome and Persia, to stabilize their tense frontier suggests that the situation between these two empires, although delicately managed, was primed for more open hostility. The situation escalated in the early seventh century CE. That’s when the Roman Empire, still trying to rebound from Justinian’s efforts to reconquer the old western Mediterranean provinces, suffered a surprising, devastating loss closer to home. Sasanian armies would take historic provinces in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. Then, more problems arose. The administration in Constantinople would watch as, over the course of two years, from 612–614 CE, the city of Jerusalem fell into Sasanian hands.

For many Romans in Constantinople, the loss of these lands was a rude, aggressive disruption of the empire’s peace. Since the foundation of Constantinople, in the early fourth century, grain shipments from Egypt had been sent directly to the Bosporus. Egypt, long the bread‐basket of distant Italy, had served Constantine’s city. So it did for three centuries when the Sasanian attack raised the terrifying prospect that the empire would now lose direct, taxed control over its food supply.

The loss of territories along the south and eastern shores of the Mediterranean made many Christians throughout the empire deeply anxious. Another source of apprehension grew from their beliefs about Jerusalem.

14.1 Jerusalem in the Sixth and Early Seventh Centuries CE

Jerusalem in the sixth century CE was a cosmopolitan city with all of the amenities a resident of the Roman Empire could have expected. It had changed quite significantly from the time of Emperor Hadrian, however. Sixth‐century residents and visitors witnessed the construction of a new, more monumentalized urban core. One spectacular street, the city’s main north–south axis – called in Latin the Cardo Maximus – benefited from this period of new investment.

The Cardo Maximus had been an important feature of Jerusalem since Hadrian’s time. Its spacious berth, connecting the northern gates of the city to the central heart of Hadrian’s Jerusalem, the Temple of Aphrodite, allowed wide, comfortable room for both foot and cart traffic. It had remained a major thoroughfare through Constantine’s day, when the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was constructed in the city center at the site where Jesus was alleged to have been buried. Three centuries later, the Cardo was extended further into the city’s southern neighborhoods. This newly paved and framed thoroughfare dramatically guided residents and pilgrims to and from the doorstep of one of Emperor Justinian’s most important buildings: the Nea Church. Remains of this wide, colonnaded street, dated to the sixth century CE, are still visible in modern Jerusalem.

Urban investment in this road attests to the ways in which even the places of daily pedestrian traffic throughout Jerusalem – not just the city’s major monuments – gripped Christian imagination throughout the sixth century. Tourism was thriving.

Around 570 CE, an anonymous pilgrim from Piacenza, Italy, came from far beyond the eastern Mediterranean shore to walk the streets of what he or she thought of as Jesus’ city. This pilgrim from Piacenza left behind a travel journal, written in Latin, with pictures of the sites that had motivated him or her to visit Jerusalem and the Holy Land. The description of the rituals which took place at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher are particularly fascinating because they show the popular allure of an important relic: a fragment of the cross on which Jesus had been executed (Exploring Culture 14.1: Jerusalem and the Lure of the “Holy Cross”).

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem at the dawn of the seventh century CE

Jews who saw or heard Christians processing around Jerusalem must have been both fascinated and frustrated. While Christian pilgrims and pious residents were marching from Constantine’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher to Justinian’s New Church, stopping at other holy sites inside and outside the city walls, the most sacred site for Jews, the ruined Temple Mount, remained an urban eyesore (Figure 14.1). Justinian’s own massive New Church, perched on its natural and man‐made hill, not only towered over the city. It looked down on this urban scar, an open wound for many members of the Jewish community who stood in the shadow of the Temple platform and Justinian’s Jerusalem.

Figure 14.1 The Temple platform, where two Jewish Temples once stood until the second was destroyed by a Roman army in 70 CE. Almost every Christian Roman emperor from the politically accommodating, like Constantine, to hard‐liners like Theodosius chose to leave it barren and desolate. In doing so, all asserted the political and cultural superiority of Christianity over Jewish history by leaving this important Jewish worship place in ruins. Beginning with the Umayyad ruler ‘Abd al‐Malik, Muslim rulers of Jerusalem – looking to distinguish themselves from other “People of the Book” – would communicate the same message taking a slightly different approach. Instead of leaving the platform in ruins, ‘Abd al‐Malik would erect the shrine, the Dome of the Rock, directly in its center. By the tenth century CE, a mosque would be constructed nearby (off to the right). The site is known in Arabic as Al Haram al Sharif (“The Noble Sanctuary”).

Photo credit: Author’s photo, 2007.

This urban effect had been carefully stage‐managed and planned. Both the Christian emperor Constantine and the Christian Justinian had decided not to invest any of the empire’s money in the ruined Temple Mount. In doing so, they argued with their silence, as countless Christian writers would allege in their sermons and writings, that Jesus’ death had rendered Jewish worship obsolete and outdated.

In Justinian’s time, these were not novel ideas; they already had a long history. Ever since the first Gospel had been composed, sometime around 70 CE and attributed to an author named “Mark,” Jesus’ followers had wrestled with the Jewish roots of their movement. Debates about how much or even whether Jesus’ Jewish and gentile followers should embrace Jewish ritual and tradition led to periods of vicious in‐fighting. These conflicts would become particularly acute during the first‐century war with Rome. They would also plan the seeds of the pernicious anti‐Jewish ideology which would circulate later.

Mark’s story about Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem exposes this undercurrent of thinking, one which would swell into more open hostility against Jews in later centuries. “Mark,” written about a generation after Jesus’ death, describes what happened in Jerusalem this way: After making the tiring journey from the Galilee region, Jesus visits the Temple; but the hour is rather later, and so he plans to return in the morning. The next day, before Jesus ascends the Temple Mount – when he will famously cleanse it of its moneychangers and curse their allegedly corrupt practices – “Mark” recounts the following odd story:

On the following day, when they came from Bethany, [Jesus] was hungry. Seeing in the distance a fig tree in leaf, he went to see whether perhaps he would find anything on it. When he came to it, he found nothing but leaves, for it was not the season for figs. He said to it, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again.” Then they came to Jerusalem. And he entered the temple…

(Mark 11.12–14 [NRSV])

Jesus and his disciples leave Jerusalem later that evening, but in the morning, one of them makes a shocking discovery. “Rabbi, look!” Peter calls out. “The fig tree that you cursed has withered” (Mark 11.21 [NRSV]).

Why has Jesus taken out his hunger pains on an innocent fruit tree for not offering him breakfast? The episode is made stranger still – and Jesus’ anger, even more irrational – by the inclusion of an authorial comment: “It was not the season for figs.” Odd though it is to us, the tale must have comforted Mark’s readers and listeners. Mark’ story about the death of the tree, cursed never to bear figs again, frames Jesus’ climactic encounter with the Temple moneychangers. “Mark” has used Jesus’ interaction with the fig tree to “predict” the Temple’s destruction – not exactly a difficult bit of mental magic since the Gospel was likely written after the Roman army had already destroyed the building.

For Jewish members of Mark’s community, people who lived through the turbulent 70s CE, “Jesus’ words” must have been comfortingly reassuring. The message that they heard in the Gospel was that Jesus “knew” the Second Temple had to be destroyed. In fact, it was as if Jesus had eerily foreseen the struggles and wars of the late first century CE, a period when every Jew in Jerusalem – not just Jesus’ followers – was now confronted with the horror of having watched a foreign army decimate their holiest site. Mark’s conviction, expressed in the vivid storytelling of his Gospel, was that the loss of the Temple was part of God’s plan.

Even though Mark’s community never referred to itself as “Christians,” their unique explanation for understanding what happened to the Temple would morph into an expressly Christian worldview. It would also have deleterious effects on Jewish–Christian relations. In the fourth century CE, Constantine would leave the Temple Mount barren to confirm that its fate was exactly as Mark’s “Jesus” predicted it was be. Two centuries later, Emperor Justinian created an newer, grander focal point for the city, doubling down on the specious assertion that the Christian faith had “replaced” Jewish worship.

This long backstory helps explain why, in 630 CE, when Jerusalem was recaptured, the Christian emperor Heraclius maintained the same “Jerusalem policy” as his Christian predecessors. Heraclius had waged a heroic military campaign. Over the course of nearly six years, he and his army had repelled Sasanian forces from lands formerly controlled by Constantinople. The emperor himself is alleged to have marched into the Sasanian capital, at Ctesiphon (outside modern Baghdad), and recovered the fragments of the “holy cross of the Lord” which the Sasanian raiders had pilfered from Jerusalem (Sebeos, History 29.99, trans. by R. Bedrosian [1985]). Yet even as these pieces of wood were being gloriously restored to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher – “There was no small amount of joy on the day they entered Jerusalem,” the seventh‐century writer Sebeos reports, writing in Armenian – centuries of rubble at the old Temple Mount remained.

The opinions of Jews who longed to recover the Temple did not matter to Christian politicians who had been raised to believe that Jesus had “predicted” its destruction all along.

Jesus’ end‐time preaching and Jerusalem before the seventh century CE

The events of 70 CE would shape Late Antique history in yet other profoundly important ways related to Christian hope for the Second Coming of Jesus.

After the Roman attack, as the Temple Mount collapsed into a wasteland, a desolate site where no one could afford to be caught wandering, Jesus’ followers faced a difficult decision: Should they continue to embrace Jesus’ Jewish heritage and identify themselves as “Jews,” or should they articulate a new name for themselves, something distinct? Not coincidentally, the first appropriation of the word “Christian” by Jesus’ followers dates to this period, after 70 CE.

A new name, however, did not soothe the crippling anxiety which many of them had about the missing Temple. “Mark” had tried to ease their concerns by suggesting Jesus had foreseen this period of difficulty, too. In a key monologue, set in Jerusalem, Jesus is alleged to have said:

“When you hear of wars and rumors of wars, do not be alarmed; this must take place, but the end is still to come. For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom; there will be earthquakes in various places; there will be famines. This is but the beginning of the birth pangs. … But when you see the desolating sacrilege set up where it ought not to be (let the reader understand), then those in Judea must flee to the mountains. … So also, when you see these things taking place, you know that he is near, at the very gates. Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place.”

(Mark 13.7–8, 14, 29–30 [NRSV])

The passage is filled with apocalyptic rhetoric. In fact, in many scholars’ opinion, it is very close to preserving the very end‐time teachings that may have earned Jesus a questionable reputation in the early first century CE. As Jesus’ speech appears here in “Mark,” however, one detail raises a red flag for historians. “Let the reader understand” is the author’s interruption, not Jesus’. It cannot be a part of Jesus’ speech because Jesus, we know, never wrote anything down.

Why does the author “Mark” interrupt this dramatic story at such a crucial point? One answer is that he wants readers to understand its relevance to their current situation. For although Jesus may have taught his disciples that the end was near in their own lifetime (“Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place”), those who lived after his execution knew differently. Nothing had happened. By choosing to dramatize Jesus’ speech now, during the war with Rome (66–74 CE), Mark reassures his community that the end was finally coming: amid the “wars and rumors of war” in the late first century CE, as “nation [was rising] against nation.”

Whether Mark was quoting Jesus cannot be known. Actual first‐hand testimony, written down in Jesus’ lifetime, preserving Jesus’ own words, does not exist. And yet, even if we admit the limitations of our evidence, we can still draw an important historical conclusion from “Mark’s” text. By the late first century CE, some of Jesus’ followers believed that the Messiah’s return would happen in Jerusalem.

Two decades after the Gospel of Mark was written, the author of Revelation would make a similar claim. (According to the text, the writer was a man named John from Patmos, an island off the coast of Asia Minor.) In his writings, this John describes a powerful vision that came to him:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them as their God; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away [in advance of the Second Coming of the Messiah]. … Write this, for these words are trustworthy and true”

(Revelation 21.1–6 [NRSV])

As this passage shows, less than a generation after “Mark’s” time, still more followers of Jesus were convinced that the Messiah’s return was intimately intertwined with visions of Jerusalem, “the holy city.” These fantastic scenes, which the writer calls a “prophecy,” were revealed to him by God through the work of “an angel” (Revelation 1.1) – a Greek word which means messenger (aggelos [ἄγγελος] pronounced “angellos”). According to John, God’s “messenger” came to him and told him, “Now write what you have seen, what is, and what is to take place after this” (Revelation 1.19).

End‐time preaching and Jerusalem during the seventh century CE

This text presents challenges for historians because its visions – of angels and demons and of stories loaded with symbolism – are so utterly unmoored from reality. In one chapter, combining prose and poetry, the writer invokes the help of another “messenger” to predict the downfall of “Babylon.” “Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great!/It has become a dwelling place of demons…” (Revelation 18.1 [NRSV]), the author wails. The reference is not to the bygone Babylonian Empire but to the world of the early Christians, living in the Roman Empire.

The text of Revelation presents the complicated struggle of Jesus’ followers trying to find their way in the cosmopolitan world of Rome as a spiritual battle with end‐time dimensions against demonic enemies, who are characterized as being offsprings of the “whore of Babylon.”

Six hundred years after Jesus’ alleged prediction of an imminent catastrophe (“Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place”), the belief that Christians were witnessing the final times remained a strong one. To Christians of the Emperor Heraclius’ reign, for example, the Persian capture of the “true cross” and the taking of the holy city of Jerusalem looked like an incontrovertible sign that the world was rushing fast towards its long‐prophesied doomsday.

One writer, Theophylact Simocotta, expressed this very anxiety. Born in the late sixth century CE, in Egypt (very little about him is known outside his monumental work of history, not even his exact birth date or birth year), Theophylact lived at the time when news of the Sasanian army’s attack on Jerusalem began to spread. He also lived to see Emperor Heraclius, in 620 CE, wage a successful counter‐attack. Writing his History shortly thereafter, Theophylact uses the figure of the Sasanian King Khusrow II to reassure Roman readers that the emperor’s victory was not only foreordained; it was a heaven‐sent sign that would hasten the end. “Be assured that troubles will flow back in turn against you Romans,” Khusrow II says. The king continues:

The Babylonian race [the Sasanians] will hold the Roman state in its power for a threefold cyclic group‐of‐seven years [ancient Greek can express this unit of measurement in one word: hebdomad]. Thereafter you Romans will enslave Persians for a fifth group‐of‐seven years. When these very things have been accomplished, the day without evening will dwell among mortals and the expected fate will achieve power, when the forces of destruction will be handed over to dissolution and those of the better life hold sway.

(Theophylact, History 5.15.5–7, trans. by M. and M. Whitby [1986])

Theophylact’s readers must have delighted in the speech since they knew, from their own vantage in the middle of the seventh century CE, that Khusrow’s “prophecy” had come true. The king had died, a Christian emperor had overturned “the Babylonian race,” and Sasanian Persia no longer threatened the people of the empire.

The emotional effect of the king’s “prophecy” must have also been reassuring, among certain Christians. For, according to Theophylact’s script, the emperor’s victory and the return of the “true cross” to Jerusalem heralded a crystal‐clear message from God: “The day without evening” – the last day – was finally near. Drawing upon belief in an imminent Second Coming, Theophylact cast a golden, almost heavenly glow on the world of the seventh‐century CE eastern Mediterranean. That light radiated upon Jerusalem.

14.2 The Social World of the Arabian Peninsula in the Sixth Century CE

As we left the reign of Emperor Justinian, we journeyed with Cosmas Indicopleustes on a voyage to the Indian Ocean. In addition to taking us far beyond the Mediterranean, allowing us to gain a view from the ground of people and customs in South and Central Asia, Cosmas sharpened our understanding of the world closer to his own home, too. During the sixth century, East Roman traders now felt comfortable sailing east through the Red Sea into the Gulf of Aden – in effect, bypassing Sasanian tax stations on the overland route. As a result, the southern Arabian peninsula became a crucial geographic pawn in the games played by these two empires.

The situation in the south peninsula must have been tense, especially as it was set against the backdrop of a fragile peace in the north. There, Arab‐Roman and Arab‐Sasanian allies had been enlisted to secure the borderlands. By 570 CE, the Sasanian King Khusrow II made a bold gamble: He invaded the territory of modern Yemen and installed a Sasanian governor to disrupt Roman traders. By 610, the two empires were locked in outright war. Virtually two entire dioceses, of the East and of Egypt, would be lost. Emperor Heraclius would respond to the challenge.

Inside the confines of the Arabian peninsula, boxed in by the hard and soft power plays of Sasanian and Roman leaders, another story was already in progress.

The interior of the Arabian peninsula held little interest to rulers of Rome or Persia. That, at least, would explain why each empire enlisted Arab families to police the northern borders and why the center of the peninsula was never a prized land‐grab for either state. The two empires’ stark political borders were not sealed cultural boundaries, however. For centuries, people of Arabia had been trading with their neighbors on all sides. Leather – for belts, tents, and military use – was a key commodity, valued by Romans and Sasanians alike. Values were another. The ability, indeed, the willingness of the local Jafnid and Nasrid families to work with the Roman and Sasanian government reveals a second, subtler kind of exchange. Certainly there were many local leaders who recognized the benefits of being politically, not just economically, engaged with people beyond the peninsula.

Daily life unfolded across the peninsula in many ways, and geographic and environmental factors played a critical role shaping this social world. Two places where we can detect the rhythms of sixth‐ and seventh‐century daily life the best are merchant oases and desert sanctuaries.

Merchant oases and desert sanctuaries

Blankets of sand cover a large portion of the peninsula, but there are significant respites. A rugged plateau called the Hijaz lines the western peninsula, along the Red Sea. The cities of Yathrib and Mecca are located here, and each in their own way is indicative of the kinds of cities one would find on the peninsula. Mecca was the center of an important sanctuary; Yathrib, a city whose name was later changed to Medina (meaning, “The City” [of the Prophet Muhammad]), the location of a vital oasis. Both shed light on daily life at the dawn of Islam.

Yathrib, in the west, was like sites as far away as the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. Medina has changed quite dramatically from its appearance in the sixth century, but the fifteenth‐century city of Birkat al‐Mawz, in modern Oman, can provide a comparative, evocative example of what it might have looked like. Situated in the shadow of the mountains, Birkat al‐Mawz is a lush settlement of mud‐brick houses surrounded by green date palms and banana trees. Local springs ensured a steady agricultural harvest both for the oasis’s residents and for families in surrounding villages who were dependent on it.

Sixth‐century Yathrib would have fit this profile. Date groves flourished around the local springs, and the oasis as a whole benefited from its position at the base of the mountainous Hijaz region. We can even sketch a rough profile of its residents. Organized in tribes, as life was elsewhere throughout the peninsula, Yathrib’s residents were a diverse group, including many Jewish families who lived at the oasis and in its vicinity.

Mecca may not have been as verdant, but it was equally thriving. Unfortunately, archaeological information about life in the sixth‐ and seventh‐century town is slim, so we need to look elsewhere to create a mental picture of it. One site which might be useful in this regard is the location of a desert sanctuary that has been excavated in modern Yemen, at Ma’rib. The sanctuary of Almaqah at Ma’rib was an important pre‐Islamic religious site (Figure 14.2). Archaeological evidence suggests that it remained in use at least through the fourth century CE, if not later. Similar sites, focused on other gods, can be found across the Arabian peninsula.

Figure 14.2 Among the people living in the southwestern Arabian peninsula were the Sabaeans, who had come to power around the eighth century BCE. The Sabaeans built this sanctuary at Ma’rib, in modern Yemen. It was dedicated to Almaqah and received worshippers for more than a thousand years, until at least the third or fourth century CE. Sabaean architecture helps scholars visualize the landscape of the pre‐Islamic Arabian peninsula. These square‐shaped pillars formed part of the sanctuary’s entrance. Similar cuboid forms appear throughout Arabia, in part because of the long‐established custom there of artists working in stone (in contrast to the Roman world where pourable concrete inspired different forms). Managed by a local family, the Ma’rib sanctuary provided a safe space where individuals from different tribes or with competing interests might come together. Both in form and in its custom, the Ma’rib sanctuary evokes the social world of other sanctuaries on the pre‐Islamic Arabian peninsula, like Mecca.

Photo credit: Eric Lafforgue/Alamy Stock Photo (2006).

The deities worshipped at these shrines were diverse. Many were related to the stars, the sun, the moon, and the cosmos, like the god Almaqah, to whom the sanctuary at Ma’rib was dedicated. Sites like these, “cut off” from other places, were considered holy and were called in Arabic haram, a word for “sanctuary.” Apart from being places where people interacted with their gods, a haram also played a key role in daily human interactions on the peninsula. The space inside the boundaries of a haram offered a neutral ground where individuals, families, and tribes could come, meet, and resolve their differences. Violence here was socially forbidden; the local families in charge of maintaining the site ensured it.

This background is crucial for getting a feel of sixth‐century Mecca, site of the holiest sanctuary in Islam. Today, skyscrapers and other ambitious buildings rise from the desert. But at the turn of the seventh century, Mecca was a desert sanctuary town. Like Ma’rib, it was the site of an important local shrine, the Ka’ba, or “Cube,” which housed a sacred black stone. By the sixth century CE, one local family, the Quraysh, maintained and administered this holy site. They proved quite capable stewards, and their leadership drew a mixture of local families and traders to Mecca.

14.3 The Believers Movement

Muhammad (b. c.570 CE) grew up in this world of merchant oases and local shrines. That might be the extent of what we can safely say about his early life. The details of Muhammad’s birth, even the year, are not preserved in any sixth‐century documents. But the lack of precise information for one man born on the Arabian peninsula should hardly be surprising, especially given how little we know about the lives of Muhammad’s contemporaries – the historian Theophylact, for example – whose writings are important for understanding the seventh‐century Roman Empire.

Stories that were told about Muhammad’s early life cannot be dismissed so readily, however. These are signs of a rich biographical tradition that his followers passed down in the centuries after his death (632 CE). It developed for good reason. The movement that Muhammad founded, which we call “Islam,” toppled the status quo in Mecca at the sanctuary of the Ka’ba and radically transformed the social and political relationship between the Arabian peninsula and the Roman and Sasanian Empires. As we will see, the circumstances that led to this transformation was a series of relentless battles waged outside the peninsula.

The success of Muhammad’s movement was also dependent on something else: the creation of a new sense of community. Their strong group identity sprang in large part from a seminal collection of Arabic texts, called the “Recitations,” or the “Qur’an.” According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad had received these revelations directly from a monotheistic deity, Allah. Then, they were written down in Arabic exactly as Allah had revealed them to him. Consisting of 114 chapters, subdivided into verses, the Qur’an remains the holiest text for Muslims today.

An essential starting point for thinking about the Arabian world of the sixth and seventh centuries is that neither the name “Islam” nor the word “Muslim” were ever used by Muhammad’s first followers in the way they have come to be used now. The text of the Qur’an makes this point abundantly clear, largely referring to the people of the earliest community as mu’minum, or the “Believers.” This Arabic word (singular, mu’min) is used almost a thousand times in the Qur’an; the word muslim, meaning “one who submits,” is used less than a hundred.

Of course, members of this community eventually did embrace the name “Muslim” as part of their identity. But the process by which that happened – the history of how the early “Believers” movement grew into a community of “Muslims” – is precisely what we’re studying. For that reason alone, it is crucial not to rush our story by starting to talk about the religion of “Islam” or seventh‐century “Muslims.” As with the followers of Jesus, who came to embrace their identity as “Christians” only about three generations after his death, so, too, would followers of Muhammad come to embrace their identity as “Muslims” only about a century after their prophet’s death.

How, when, and why that happened are historical questions. They cannot be passed over because we think we know how the story of Islam may have started. One text from the seventh century CE confirms the workings of this complicated process.

The Constitution of Medina

For the members of the earliest community, Muhammad’s companions, it was their identity as “Believers” which brought them together (Key Debates 14.1: Muhammad’s “House” and the Development of Early Mosque Architecture). The importance of this term of self‐identity is substantiated in a document, written in Arabic, that is not contained in the Qur’an. It was written around 622 CE, the year in which Muhammad left his home in Mecca to move north to the city of Yathrib. This text is known as the “Constitution of Medina,” also called the umma document.

Unfortunately, no seventh‐century copy of this artifact has yet been discovered, but scholars are virtually certain it existed. The text is known from the reports of two later writers – one living in the mid‐eighth century CE, another in the ninth century CE. Although historians are naturally trained to be skeptical of documents attested in later authorities, scholars who have studied the text of the “Constitution of Medina” are virtually unanimous that it dates to the seventh century CE. For one, its language is filled with many archaic Arabic expressions dated to that time period. Secondly – and perhaps more significantly – it presents a view of Muhammad’s movement that departs in radical ways from the stories which later developed about early Islam.

The events that led to the birth of this document are important. Muhammad’s “emigration” to Yathrib in 622 CE, or hijra, would come to mark a crucial turning point for the Believers, largely because it was not a journey that happened under auspicious circumstances. Twelve years earlier in Mecca, in 610 CE – perhaps around the time he was forty, if his birth tradition can be accepted – Muhammad had begun to receive his revelations. Over the course of the next decade, he had brought this new, monotheistic message to the residents of his hometown. To the family in charge of the Ka’ba, people who had built a name for themselves and their city by successfully administering and growing their sanctuary, Muhammad’s teachings aroused suspicion and maybe even fear about whether he intended to upset the status quo. In 622 CE, as a result of disagreements with the Quraysh, the family in charge of the sanctuary, Muhammad and his companions sought refuge in Yathrib.

Muhammad’s “emigration” to Yathrib would prove foundational to his movement’s development. Shortly after Muhammad’s death, his followers would start to record time around their memory of that journey; the year of the emigration would now mark “year one” in their new community calendar. (Following the precedent for recording Christian time with “A.D.” [anno Domini, “year of our Lord”], this new method of telling Islamic time is now abbreviated “A.H.,” or anno Hegirae [“year of the hijra”].) The city of Yathrib itself would eventually come to be known by a different name, al‐medinat al‐nabi, “the city of the prophet,” or Medina, in Saudi Arabia.

The “Constitution of Medina” was written shortly after Muhammad and his companions arrived in Yathrib. It outlines a settlement that was negotiated between Muhammad, his companions, and the leading families of Yathrib who were supporters of his movement. Throughout the text, the people who belong to Muhammad’s movement are called the “Believers.” The document as a whole articulates a plan for cooperation and mutual respect between participating parties, many of whom included local Jewish tribes living in this area of the Arabian peninsula:

Whoever follows us among the Jews shall have assistance and equitable treatment; they shall not be oppressed, nor shall [any of us] gang up against them. The peace of the Believers is indivisible. No Believer shall make a [separate] peace to the exclusion of … [another] Believer in fighting in the path of God, except on the basis of equity and justice among them. … The Jews of [the local tribe] Banu ‘Awf are a community [umma] with the Believers. (The “Constitution of Medina,” sections 16–17, 25, trans. by F. Donner, Muhammad and the Believers at the Origins of Islam [Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010], pp. 227–232, based on the text from Ibn Ishaq [d. 767 CE])

The “Constitution of Medina” is an extraordinary source because it shows that Muhammad’s vision for his early seventh‐century community, or umma, was large enough to include other monotheists, like Yathrib’s local Jewish families.

The constitution itself carried with it the authority that came from Muhammad’s stature as an “apostle of God,” the one to whom Allah had made his revelations. As the document states, “God [Allah] supports whatever is most righteous and upright in this treaty.” This political allegiance – between Muhammad’s emigrant group and his supporters in Yathrib – established a coalition that would eventually wrestle control of the Ka’ba from Mecca’s leaders. It was also rooted in a shared commitment to the power and meaning of the prophet’s “Recitations.”

An apocalyptic component

In order to gain a fuller perspective of the social profile of the “Believers,” we should examine some of the characteristics we can glean about them from the Qur’an. According to Islamic commentators, Muhammad’s first revelations had come between 610 and 622 CE while he was living in Mecca. After the emigration to Yathrib, more followed. Taken together, these texts comprise the 114 chapters, or suras, of the Qur’an.

Among the many historical details that can emerge from a close reading of the text are two that deserve comment here. The first relates to the urgent nature of Muhammad’s message. In many suras, listeners and readers are urged to change their ethical behavior because of the looming nature of the end times. This cosmic catastrophe lurks in the following verses, thought to have been revealed at Mecca:

How many a sign is there in the heavens and the earth, which they pass by with face averted! And most of them believe not in God [Allah] except that they attribute partners (to Him). Deem they themselves secure from the coming on them of a pall of God’s punishment, or the coming of the Hour suddenly while they are unaware?

(Qur’a̵n 12 [Mecca]: 105–107, trans. by M. Pickthall [1938])

Here, those who have not joined the community of Believers are castigated for not recognizing the divine signs “in the heavens and the earth,” cosmic signs which forecast the coming wrath of Allah. By contrast, those who have joined the movement, people who now follow the revelations to Muhammad, know that God’s “punishment” demands they reset their moral and spiritual compass, especially when one considers the “coming of the Hour” (Political Issues 14.1: What Effect Did the Rise of Islam Have on Daily Life in the Christian Roman Empire?).

When did the early Believers expect this “Hour” to arrive exactly? It is an important question. As we have repeatedly learned from our studies of Hellenistic Judaism and early Christianity, apocalyptic thinking – even when it dwells on a Last Judgment and the end of the world – does not need to specify an imminent, or immediate, event for the speaker’s message to have a certain energetic quality. What, then, can we deduce about the Believers’ movement?

Evidence from the Qur’an suggests that they not only understood “the Hour” was approaching, soon, but that some of the first signs of this divine reckoning had already come: “The Hour drew near and the moon was rent in two,” reads one sura (Qur’a̵n 54 [Mecca]: 1–5, trans. by M. Pickthall (1938]). “And if they behold a sign they turn away and say: ‘Prolonged illusion.’” The text implies that people in Muhammad’s lifetime have already been exposed to the warning signs that the “Hour” was near. It chastises anyone who interprets these signs as an “illusion.”

An initial focus on Jerusalem

A second aspect of the Believers’ movement is apparent when examining the chapters of the Qur’an. We can see that the Believers’ understanding of which direction to pray was not the one handed down through Islamic tradition. Today, Muslims pray towards Mecca. The earliest Believers – driven from that desert sanctuary city, in effect, locked out of Muhammad’s hometown – prayed the opposite direction: to Jerusalem.

From their earliest formation, a shared “direction of prayer” (qibla, in Arabic) had contributed to the Believers’ strong sense of communal identity. When, in 630 CE, Muhammad marshaled the forces in Yathrib to march on Mecca, that community was given a new directional focus: the Ka’ba. Cleansing the shrine of its “pagan” character and taking forceful control of the city from the tribe who had managed it, Muhammad thus established Mecca as the center of the Believers’ movement.

One important hint that the community’s first qibla, or prayer direction, was changed after the emigration to Yathrib appears at sura 2.

And when we made the House [at Mecca] a resort for people and a sanctuary [saying]: Take as your place of worship the place where Abraham stood. … The foolish of the people will say: What has turned them from the prayer direction (qibla) which they formerly observed? Say: To God belong the east and the west. He guides whom He wills to a straight path. … And we appointed the prayer direction which you formerly observed only that we might know him who follows the Messenger from him who turns on his heels.

(Qur’a̵n 2 [Medina]: 124–126, 142–143, trans. by M. Pickthall, slightly modified [1938])

Although the text of the Qur’an does not name the city from which the Believers have turned their prayer, biographies of the prophet, like the one written by Ibn Sa’d, make clear that “the prayer direction which [the Believers] formerly observed” was Jerusalem.

There is also good circumstantial reason to think Jerusalem was the focus of their initial prayer. Many of the Believers’ contemporaries, both Christians and Jews, thought that Jerusalem would be the setting for the explosive end‐time events described in their own traditions. For a community steeped in apocalyptic imagery, as Muhammad’s early community was, Jerusalem would have been a natural focus for their prayers. The Believers’ awareness of this wider Mediterranean conversation – about the importance of Jerusalem in God’s plans – would also explain why, in their military expansion, they soon made plans to seize it (Working With Sources 14.1: The Hunting Lodge at Qusayr ‘Amra, Jordan; Figures 14.3 and 14.4).

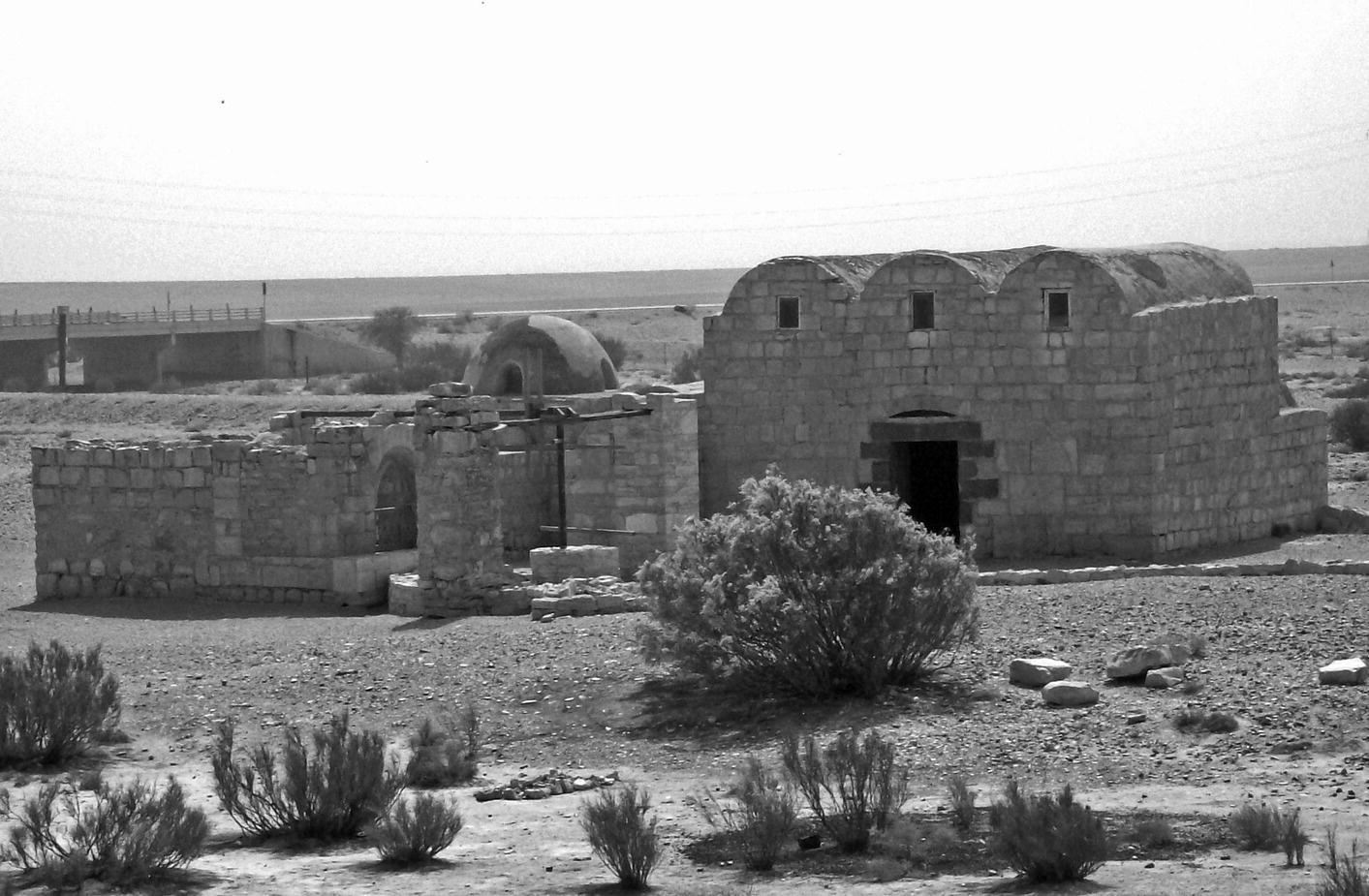

Figure 14.3 From the outside, the hunting lodge at Qusayr ‘Amra appears to be a modest structure whose domes and vaults, nevertheless, give it a dramatic profile against the desert landscape. Built of local limestone, the lodge sits in an area east of the Jordan River valley (modern Jordan, about 50 miles outside Amman) at the base of a wadi, or canyon, that fills with rain. In the foreground, at left, is a cistern for storing water. The lodge’s entrance, with its dramatic triple‐vaulted room, lit by high windows, is at right. This photograph of the property faces south. Early to mid‐eighth century CE.

Photo credit: © Walter Ward, 2007.

Figure 14.4 In contrast to its unadorned exterior, Qusayr ‘Amra’s interior walls, including its entry vaults, are awash in frescoes. Some painted scenes show women nude, alluding to the luxuries of the bath. Others, such as these two panels, promoted values that were important to the Umayyad elite. Located on the east vault of the reception hall, they are part of thirty‐two scenes which show ordinary men at work: transporting materials, pounding anvils, carving stone. Although their message is perhaps not immediately apparent today, the lodge’s owner may have commissioned these scenes of daily life because he saw building, like patronage, as a metaphor for good governance – a value shared by the Umayyads’ neighbors. Early to mid‐eighth century CE.

Photo credit: © B. O’Kane/Alamy Stock Photo.

Summary

By the beginning of the eighth century CE, individuals within the “Believers” community will have embraced the name “Muslim” to refer to their distinctive beliefs; and they will have taken political control of Egypt, Syria, and Sasanian Persia, as well as Jerusalem. There, the dynasty of rulers known as the Umayyads would make a powerful statement about their possession of the city. They would build a shrine, the Dome of the Rock, directly on the Temple Mount, a site which had lain barren since 70 CE under all Christian Roman emperors. The world of the Arabian peninsula, out of which the army of Muhammad’s believers had emerged, was not cut off or isolated from the broader social and cultural currents of the Mediterranean, however.

Apocalyptic thinking, which was prevalent in both the kingdoms of western Europe – in the territories that had once been under Roman control – and the Roman Empire in the east was one such shared characteristic. The political maneuvering of the Roman and Sasanian states in and around the southern Arabian peninsula during the late sixth century CE also may have shaped the society and culture of cities like Mecca and Yathrib. And while, over the next two hundred years and beyond, Muhammad’s followers would expand their territorial holdings through military victory, their conquests also came with significant degrees of diplomacy and cultural negotiation.

Even their vision of a divinely inspired government was little different than the ideology which had underpinned the Sasanian Empire before its collapse and which was currently upholding the Roman Empire in Constantinople.

Study Questions

- Name some reasons why Jerusalem was an important city for Christians at the start of the seventh century CE.

- What is the “Constitution of Medina,” and how does it shed light on the community founded by Muhammad and followers?

- What beliefs, ideas, and values did Muslims and Christians share in the seventh and eighth centuries CE? Be sure to cite specific evidence to support your analysis.

- From a historical perspective, would you say that individuals and communities who hold monotheistic beliefs (“belief in one God”) are fundamentally unable to live in a pluralistic society?

Suggested Readings

- Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2004).

- Fred Donner, Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2012).

- Jodi Magness, The Archaeology of The Holy Land: From the Destruction of Solomon’s Temple to the Muslim Conquest (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Marcus Milwright, An Introduction to Islamic Archaeology (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010).