CHAPTER 8

SERIAL KILLERS

“I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing.”

—H. H. Holmes in confession, 1896

Fear enveloped New York city in the summer of 1977. One tabloid front page summed up the feeling many were experiencing: “NO ONE IS SAFE FROM SON OF SAM.” The sequential, stalking behavior of a serial killer on the loose creates an anxiety that invades entire neighborhoods, even cities. The Times’s headline on August 1, 1977, may have been more muted, more factual: “.44 Killer Wounds 12th and 13th Victims.” But no one was confused about what it meant.

DISMAY IN WHITECHAPEL: TWO MORE MURDERED WOMEN FOUND

The Whitechapel fiend has again set that district and all London in a state of terror. He murdered not one woman but two last night, and seems bent on beating all previous records in his unheard-of crimes. His last night’s victims were both murdered within an hour, and the second was disemboweled like her predecessors, a portion of her abdomen being missing as in the last case. He contented himself with cutting the throat of the other, doubtless because of interruption. Both women were streetwalkers of the lowest class, as before.

These crimes are all of the most daring character. The first woman was killed in the open roadway within a few feet of the main street, and though many people were within a few feet, no cry was heard. This was at midnight; before 1 o’clock the second victim was found, and she was so warm that the murder must have taken place but a few minutes before. This was in Mitre-square, which is but a few blocks distant from the Bank of England, in the very heart of the business quarter. The square is deserted at night, but is patrolled every half hour by the police.

These make six murders to the fiend’s credit, all within a half-mile radius. People are terrified and are loud in their complaints of the police, who have done absolutely nothing. They confess themselves without a clue, and they devote their entire energies to preventing the press from getting at the facts. They deny to reporters a sight of the scene or bodies, and give them no information whatever. The assassin is evidently mocking the police in his barbarous work. He waited until the two preceding inquests were quite finished, and then murdered two more women. He has promised to murder 20 in all, and has every prospect of uninterrupted success.

—October 1, 1888

Associated Press Dispatches

London, Sept. 30—This morning the whole city was again startled by the news that two more murders had been added to the list of mysterious crimes that have recently been committed in Whitechapel. It was known that another woman had been murdered, and a report was also current that there was still another victim. This report proved true. The two victims, as in the former cases, were dissolute women of the poorest class. That the motive of the murderer was not robbery is shown by the fact that no attempt was made to despoil the bodies.

The first murder occurred in a narrow court off Berners-street at an early hour in the morning beneath the windows of a foreigners’ Socialist club. A concert was in progress and many members of the club were present, but no sound was heard from the victim. The same process had been followed in the other cases. The woman had been seized by the throat and her cries choked, and the murderer, with one sweeping cut, had severed her throat from ear to ear. A clubman on entering the court stumbled over the body, which was lying only two yards from the street. A stream of warm blood was flowing from the body into the gutter. The murderer had evidently been disturbed before he had time to mutilate his victim.

The second murder was committed three to four hours later, in Mitre-square, five minutes’ walk from the scene of the first crime. The body of the unfortunate woman had been disemboweled, the throat cut, and the nose severed. The heart and lungs had been thrown aside, and the entrails were twisted into the gaping wound around the neck. The work of dissection was evidently done with the utmost haste. The doctors, after a hasty examination of the body, said they thought it must have taken about five minutes to complete the work of the murderer, who then had plenty of time to escape.

Mitre-square, the scene of the second murder, is a thoroughfare. Many people pass through the square early on Sunday morning on their way to prepare for market in the notorious Petticoat-lane. The publicity of the place adds to the daringness of the crime.

The police, who have been severely criticized in connection with the Whitechapel murders, are paralyzed by these latest crimes. As soon as the news was received at police headquarters a messenger was dispatched for Sir Charles Warren, chief commissioner of police, who was called out of bed and at once visited the scene of the murders. The inhabitants of Whitechapel are dismayed. The vigilance committees formed after the first crimes had relaxed their efforts to capture the murderer. The Berners-street victim was Elizabeth Stride, a native of Stockholm, who resided in a common lodging house. The name of the other victim is not known. Dr. Blackwell, who was called to view the remains of the Berners-street victim, gave it as his opinion that the same man, evidently a maniac, had committed both murders. The Berners-street victim had evidently been dragged back by a handkerchief worn around the throat.

Detail of a New York Times front-page headline of October 1, 1888.

NOTE: The Whitechapel district murderer, who came to be known as Jack the Ripper, was never caught. Although other unsolved murders in the district in 1888 were attributed by some to the Ripper, researchers suggest that five deaths, including that of Ms. Stride, are most persuasively linked.

HOLMES COOL TO THE END

Murderer Herman Mudgett, alias H. H. Holmes, was hanged this morning in the county prison in Philadelphia for the killing of Benjamin F. Pietzel. The drop fell at 10:12 o’clock, and 20 minutes later he was pronounced dead.

Holmes was calm to the end, even to the extent of giving a word of advice to Assistant Superintendent Richardson as the latter was arranging the final details. He died as he had lived—unconcerned and thoughtless of the future. Even with the recollection still vividly before him of the recent confession, in which he admitted the killing of a score of persons in all parts of the country, he denied everything, and almost his last words were a denial of any crimes except the deaths of two women at his hands by malpractice.

In the murder of the several members of the Pietzel family, he denied all complicity, particularly of the father, for whose death he stated he was suffering the penalty. Then, with the prayer of the spiritual attendants still sounding in his ears, the trap was sprung, and the execution that terminated one of the worst criminal stories known to criminology was ended.

While the exact time of the execution was unannounced, it was supposed that the hour would be about 10 o’clock. Two hours before that time, however, those who were to attend began arriving, but admission to the prison was denied everyone except those officials in direct touch with the institution. The gates were then opened, and the fourscore having tickets pressed into the inner court. Sheriff Clements had preceded the crowd, and was awaiting the arrival of those comprising his jury, that they might be sworn.

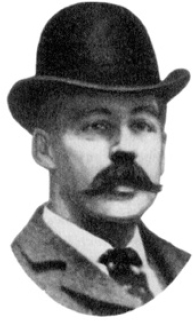

Portrait of Herman Mudgett, aka H. H. Holmes, mid 1800s.

The jury comprised six physicians and a like number from other walks in life, all prominent in their respective stations. In response to the calling of their names they ranged about the desk behind which stood Sheriff Clements, and then solemnly swore “to witness the execution of Herman W. Mudgett, alias H. H. Holmes, and certify the time and manner of such execution according to law.”

Many prominent men were in attendance, notable among whom were Dr. MacDonald of Washington, the famous criminologist; Det. Frank Geyer, who conducted the case, and Lawyer Rotan, who conducted the defense of Holmes during the trial.

Mr. Rotan was early at the prison, but had been preceded by the Rev. Father Dailey and the Rev. Father MacPake, who administered the last rites to the condemned man. They arrived shortly after 6 o’clock, and remained with him last evening until 10:30.

The deathwatch was then kept by Keeper George Weaver, who remained until 7 o’clock this morning. Weaver said this morning that Holmes had retired about midnight and slept soundly until called at 6 o’clock. So sound were his slumbers that twice was he called before awakening when the arrival of the reverends was announced. They were come to administer the sacrament of communion. For nearly two hours they remained in the cell, and then were succeeded by Lawyer Rotan, the legal adviser of Holmes.

While they were talking, breakfast was served, and Holmes seemed to heartily enjoy the meal. It was substantial, but plain, consisting of eggs, toast and coffee. “He enjoyed it more than I could,” remarked Mr. Rotan. “He is the most cool and possessed of all in any way connected with the case.”

Shortly before 9 o’clock, Holmes prepared to dress himself. Contrary to the general custom, he refused to don a new suit, but arrayed himself in trousers, vest, and cutaway coat. Collar and necktie were, of course, not worn, but their place was taken by a white handkerchief knotted about the neck.

Ten o’clock had just sounded when a call came from the cell corridor for Sheriff Clements. He had been gone but a moment when the doors leading through the long corridors in which was placed the gallows were opened, and two by two, led by the sheriff’s jury, the party passed down. The gallows was halfway down the corridor, and to either side was a high partition that, once through the doors, shut off any view of the approach of the condemned as he came to the scaffold. The greatest stillness prevailed among the group watching for the first glimpse of the condemned.

Preceded by Sheriff Clements and Superintendent Perkins, Holmes soon stepped onto the trap. On the right was Father Dailey, to the left, Father MacPake, and bringing up the rear were Lawyer Rotan and Assistant Superintendent Richardson. The little party stood for a moment and then Holmes stepped forward and spoke.

He spoke slowly and with measured attention to every word; a trifle low at first, but louder as he proceeded, until every word was distinctly audible. “Gentlemen,” he said, “I have a very few words to say. In fact, I would make no statement at this time except that by not speaking I would appear to acquiesce in life in my execution. I only want to say that the extent of my wrongdoings in taking human life consisted in the deaths of two women, they having died at my hands as the result of criminal operations, I wish to also state, however, so that there will be no misunderstanding hereafter, I am not guilty of taking the life of any of the Pietzel family, the three children or father, Benjamin F. Pietzel, of whose death I am now convicted and for which I am today to be hanged. That is all.”

As he ceased speaking, he stepped back, and, kneeling between Fathers Dailey and MacPake, joined with them in silent prayer. Again standing, he shook the hands of those about him, and then signified his readiness for the end.

Coolest of the entire party, he even went to the extreme of suggesting to the Assistant Superintendent Richardson, that the latter not hurry himself. “Take your time: don’t bungle it,” he remarked, as the official exhibited some little haste, the evident outcome of nervousness. Those were almost his last words. The cap was adjusted. A low-toned query: “Are you ready?” and an equally low-toned response, “Yes, good-bye,” and the trap was sprung.

The neck was not broken, and there were a few convulsive twitches of the limbs that continued for about ten minutes. “But he suffered none after the drop,” said Dr. Scott, the prison physician. The trap was sprung at precisely 10:12, and 15 minutes later Holmes was pronounced dead.

The body was placed in a vault in Holy Cross Cemetery. The last act at the vault was performed at Holmes’s express command. The lid of the coffin was taken off and the body was lifted out and laid on the ground. The bottom of the coffin was filled with cement, and the body was replaced in the coffin and covered with the cement. It was Holmes’s idea that this cement would harden around his body and prevent any attempt at grave robbery. The coffin was left in the receiving vault under the guard of two watchmen. Tomorrow afternoon the body will be interred in a grave in the cemetery.

Holmes made no will and left no confession. The two women referred to by Holmes in his confession from the scaffold were Julia Connor of Chicago, who, with her daughter, was believed to have been murdered by him, and Emily Cigrand of Anderson, Ind.

Holmes the Murder Demon

Harry Howard Holmes was only 36 years old, but into those few years he had succeeded in crowding a series of crimes that many older scoundrels had achieved only in a much longer life. The man who has just received the heaviest penalty of the law was convicted of one murder. Three more were in evidence against him. He had apparently planned to kill three more persons, and he accused himself of having taken the lives of 27 human beings. After giving this list, the charges against him of bigamy, train robbery, horse stealing and general swindling sink into insignificance.

H. H. Holmes is the name by which this slayer will be enrolled in the list of the world’s great criminals. Herman Webster Mudgett was his real name, and he was born in Gilmanton, N.H., May 16, 1860. By what stages of wickedness he rose to the crime of murder is not known, or when he committed his first great crime. He says it was in 1886. At that time he was the proprietor of the “Castle,” in Chicago, which subsequent research by the police has shown to be a veritable man trap, with furnaces, concealed rooms, cells and many other devices for putting victims speedily and secretly out of the way. Whatever he did there, he first appeared prominently in September 1894, to assist in the identification of a man who was found dead in a room on Callowhill Street in Philadelphia.

This man was Benjamin F. Pietzel, for whose murder Holmes has been hanged. Pietzel, under the name of B. F. Perry, had hired the house, ostensibly as a dealer in patents. On Sept. 4 his body was found there, the face burned, and indications of an explosion. A coroner’s jury decided that death was due to congestion of the lungs, caused by inhalation of flames, chloroform or some poisonous drug. Whether it was suicide or murder was a mystery.

The next development was a notice to the Fidelity Mutual Life Association of Philadelphia that Perry was really Benjamin F. Pietzel, and that his widow held a policy for $10,000 insurance on his life. The notice came from Jephtha D. Howe, a lawyer of St. Louis. In the investigation, H. H. Holmes appeared to assist in the identification of the body, as well as the dead man’s daughter, Alice. The insurance company was satisfied, and the money was turned over. Alice was the only one of a family of a widow and five children to appear on the scene. Apparently the incident was ended.

But the insurance company had a detective, Inspector W. E. Gary, who was suspicious of wrongdoing somewhere. The next month, when he was in St. Louis, he was given the confession of M. C. Hedgepeth, a convicted train robber who laid bare the whole scheme. Holmes had visited him in jail, and had asked the name of a lawyer to assist in a fraud upon an insurance company. This was to insure Pietzel for $10,000, substitute a corpse and collect the money. Hedgepeth said he recommended J. D. Howe, and for this was to receive $500 out of the money, but he had never been paid. The company began an investigation, evidences of fraud multiplied. Holmes was eventually arrested in Boston, but, strangely, on a telegram from Fort Worth, Texas, accusing him of horse stealing. Mrs. Pietzel was also arrested.

Then Holmes made confession No. 1. He admitted a conspiracy to defraud the insurance company and said Pietzel was alive, with three of his children, in South America, and his supposed body was a cadaver bought in New York. Holmes, Pietzel, Howe, the lawyer, and Mrs. Pietzel were indicted for conspiracy to defraud.

In the meantime, many suspicious facts became known. No trace could be found of Pietzel or his children. Holmes made a second confession, that it was Pietzel’s body that had been found, and that Pietzel had probably committed suicide; that he (Holmes) had discovered this, and then arranged the body and left it in the house where it was found. This made necessary a second indictment, under which he was convicted, and sentence was deferred.

Here comes in the most dramatic part of the story—the tracing of the three children, whom Mrs. Pietzel had entrusted to Holmes at the time of the identification of her husband. She was anxious to see them. Holmes was told he was suspected of murdering the father and the son, Howard, and the daughters, Alice and Nellie. He was told he could clear himself partially by telling where the children were. He said he had given them to a Miss Williams, who had taken them to London.

This was not believed. There were ugly rumors about the disappearance of two sisters, Nettie and Minnie Williams, last seen in the care of Holmes, and a piece of real estate in Fort Worth, Texas, was found to have been conveyed by them to Pietzel under the name Benton T. Lyman. Holmes said that Minnie, in a moment of passion, had killed Nettie, and he had shielded her by sinking the body in the lake at Chicago.

So strong became the suspicions of a hideous crime that Det. Frank P. Geyer of the Philadelphia force was put on the track of the missing children. While the police were gathering evidence to prove Holmes guilty of the father’s murder, Geyer revealed a more horrible chapter. He followed the footsteps of Holmes and the three children, and found where he killed the boy Howard and burned his body at Irvington, near Indianapolis; dug up the corpses of the two little girls in a cellar, in Toronto, and found their toys even, in the houses where the crimes were committed. The detective found that Holmes had been leading three parties around the country from place to place. One was composed of the broken-hearted wife, with her oldest daughter, Dessie, 16 years of age, and her one-year-old baby daughter, the woman continually deceived with promises of soon meeting husband and children. Another was made up of the boy and his two sisters. In the third was Holmes and his third wife, Georgiana Yohe. Neither party, Holmes excepted, knew of the others. It is believed that Holmes was planning to kill the mother and two remaining children had not his arrest at Boston interfered.

The finding of the children’s bodies and the proofs connecting Holmes with the death of Pietzel had by this time roused a feeling of horror toward Holmes that overran the whole country. On Sept. 12, 1895, he was indicted for the murder of Pietzel. His trial began Oct. 28, and on Nov. 2 he was found guilty. On Nov. 28 he was sentenced to death.

As to the motive for these crimes, one theory is that Holmes feared that Pietzel, who had been his partner for years, might betray him when on a drunken carouse. By killing him he could get rid of an embarrassing witness and make some money at the same time. Holmes’s behavior since his sentence has been marked by great hardihood. His third and last confession is a document, which, if true, marks him as one of the most depraved monsters of any age. In it he excuses himself for his crimes by calling himself a “degenerate.” He gives a list of 27 murders, mostly committed in his “Castle” in Chicago—men and women whom he lured there, forced to give up their property, and then killed, and whose bodies he sold for use in dissecting rooms. He tells of all these with an attention to detail which is sickening. Holmes, as a bigamist, appears to have been married under his real name first near his native town, to Clara A. Lovering, on July 4, 1878. From her he obtained a divorce in February 1987, in Illinois. Two weeks before this, he had married Myrta Z. Belknap, with whom he lived at Wilmette, Ill., under the name of Holmes. Next, without even the formality of legal separation, he was married, as Henry Mansfield Howard, at Denver, Col., to Miss Georgiana Yohe. This last was the woman who was with him in all his later wanderings.

An artist’s rendering of H. H. Holmes’s “Murder Castle” hotel in Chicago, April 1896.

One of the last scenes in this horrible drama took place April 17—Holmes’s reception into the Catholic Church. For five or six weeks the Rev. P. F. Dailey, in whose parish the Moyamensing Prison is situated, had been laboring with him. He became convinced that Holmes’s change of heart was sincere. On the day mentioned, assisted by a band of Franciscan monks, and aided by all the ritual that could be carried out in a cell in Murderers’ Row, Holmes was given the rite of baptism.

On April 29, Holmes sent a communication to Gov. Hastings asking for a respite. He asserted his innocence of many of the charges against him, and said that he wanted to get himself into a spiritual condition to meet his God. His attorney intimated that Holmes would divulge the names of men who aided him in his crimes. The governor, however, refused the application.

After the first of the month, Holmes lost his cheerfulness and became morose, seeming to realize his position. He made a will, in which, it is said, he made provision for each of his wives, and also for Mrs. Pietzel.

Holmes’s Many Confessions

If the “murder confessions” which Murderer Holmes wrote can only partially be believed, he was without a peer as a bloodthirsty demon. His recent ingenious “confession,” wherein he claimed to have killed 27 persons, was disproved, partly, at least, by the appearance of several of the so-called victims; but Holmes’s object in making the “confession” was realized—the obtaining of a sum, said to be $7,500, to have been settled upon the criminal’s 18-year-old son.

Holmes was captured in Boston, Mass., in the latter part of 1894 by Owen Hanscom, the deputy superintendent of police, upon the strength of a telegram from Fort Worth, Texas, where he was wanted for horse stealing and other charges. At that time, officials of the Fidelity Mutual Life Association of Philadelphia were hot on Holmes’s trail for defrauding the concern out of $10,000 in connection with Pietzel’s death, the latter having been insured for this amount, and, as the accused believed horse stealing to be a high crime in Texas, he voluntarily confessed to Deputy Superintendent Hanscom to the insurance fraud. He did not dream that he was then suspected of the murder of Pietzel. He came to Philadelphia and expressed a willingness to be tried here on the conspiracy charge in preference to that of horse stealing at Fort Worth.

Before leaving Boston, Holmes made this “confession” to Mr. Hanscom: “When I concluded it was time to carry out our scheme to defraud the insurance company I secured a ‘stiff’ in New York and shipped it in a trunk to Philadelphia. I turned the check for the trunk over to Pietzel on the Sunday nearest the first of September. I instructed him how to prepare the body, and in three hours we were on our way to New York. Ten days after the payment of the money I saw Pietzel in Cincinnati. I took the three children to that city, where the father saw them.

“Pietzel agreed to go south, and he took one child. Howard. I took the two girls to Chicago because I had business there. We all met again in Detroit. Pietzel took the children and went to South America. During all this time Mrs. Pietzel knew her husband was alive, but she did not know that he had the children. To keep Mrs. Pietzel away from her husband, I had to tell her he was here and there, traveling from one city to another.”

This was the first of a number of alleged admissions that Holmes subsequently made. The insurance officials had good grounds for believing Holmes had murdered Pietzel and the three children. So when the prisoner arrived in Philadelphia he was urged to make another confession. He did so, but it varied from the one he made in Boston. It graphically narrated how the body was substituted for Pietzel in the Callowhill Street house, and its identification by Alice Pietzel as that of her father. Holmes also related how the money was received from the insurance company and its division between Mrs. Pietzel, Jephtha D. Howe, the St. Louis lawyer, and himself. In this “confession” Holmes accused Howe of receiving $2,500 for his share in the transaction.

Soon after Holmes was taken to Philadelphia, Det. Geyer visited him in the county prison in relation to the finding of the body at Callowhill Street, Sept. 4, 1894. After an hour’s conversation with the wily Holmes the detective emerged from the prison with a “confession,” in which the accused said that the body was not that of Pietzel, but was one substituted to defraud the insurance company.

Holmes honored Mr. Geyer a week later with still another “confession.” “Mr. Geyer,” he said, “that story I told you about a substitute body is not true. It is the body of Benjamin Pietzel, but I did not murder him or his children. On Sunday morning, Sept. 2, I found Pietzel dead in the third story of the Callowhill Street house. I found a note in a bottle telling me that he was tired of life and had finally decided to commit suicide. He requested me to look after the insurance money, and take care of his wife and family. I then fixed up the body in the position it was found. These children you speak of are all right. They are with Minnie Williams in London.”

When the bodies of Nellie and Alice Pietzel were unearthed in Toronto, Holmes denied having killed them. When Howard’s charred bones were located in a stove in Irvington, Ind., Holmes denied any knowledge of the lad’s death. When the murders of Minnie Williams and her sister were discovered, Holmes said Minnie killed Nancy in a jealous frenzy, and he buried the body in Lake Michigan. He denied having put Minnie to death to secure her property. The disappearance of Emily Cygrand was traced to Holmes, hut the criminal said he knew nothing of the girl’s fate. The partially consumed bones found in the Chicago “Castle” are known to be those of some of Holmes’s victims.

The last time that Holmes was taken to the district attorney’s office to “confess,” Mr. Graham lost patience with him. “Holmes, you are an infernal, lying murderer,” Mr. Graham said. “I will hang you in Philadelphia for the murder of Benjamin Pietzel.”

Holmes’s nerve was still with him, and he said “I defy you. You have no evidence to prove me guilty.”

Mr. Graham looked with disgust and determination at Holmes and said: “You will surely hang in Philadelphia for murdering Benjamin Pietzel.”

—May 8, 1896

DESALVO, CONFESSED “BOSTON STRANGLER,” FOUND STABBED TO DEATH IN PRISON CELL

Albert H. DeSalvo, who became known as the “Boston Strangler,” was found stabbed to death at Walpole State Prison this morning. The prison authorities said the 40-year-old inmate’s body was discovered in his cell bed in the prison’s hospital wing at 7 o’clock. DeSalvo, who worked as an orderly in the hospital, was said to have died of multiple stab wounds.

The Norfolk County district attorney, George Burke, said that a possible suspect had been questioned, but that no arrest had been made.

Although DeSalvo confessed the details of the slayings of 13 women from the Boston area to a psychiatrist and became widely known as the “Boston Strangler” through a book and movie of the same name, he was never tried for those crimes. Later DeSalvo retracted the confession.

“The only problem we had with Albert DeSalvo was his trafficking in drugs,” said Mr. Burke. “We don’t know if this murder is drug-connected. It’s possible … anyone who deals in drugs has enemies, because it’s competitive.”

The medical examiner, Nolton Bigelow, said it appeared DeSalvo had been dead for “up to 10 hours.”

John Irwin, chief of the Criminal Investigations Division of the State Attorney General’s Office, recalled today that there was considerable doubt among law enforcement officers over whether DeSalvo was indeed the strangler.

The slaying of the 13 women—most of them strangled with a stocking—between 1962 and 1964 spread terror through the Greater Boston area, and the Boston Strangler became a part of the folklore of crime.

Tried and Convicted

Some police officials who investigated the case, however, believed that only five of the victims were killed by the same assailant. Mr. Irwin recalled that some police officers were satisfied that DeSalvo committed all the crimes, while others believed he might have committed some.

DeSalvo was tried and convicted in January, 1967, for a separate series of crimes, including burglaries, assaults and sex offenses against four other women.

He was at first ruled mentally unable to stand trial, but F. Lee Bailey, the defense attorney, entered the case and won him a trial.

He had DeSalvo examined by a psychiatrist, Dr. Robert R. Mezer, who shocked the courtroom when he testified: “DeSalvo told me he was the strangler…. He told me he strangled 13 women … and he went into details of some of them, telling me some of the most intimate acts he committed.”

“Gleaned the Details”

Mr. Bailey argued, unsuccessfully, that DeSalvo should be found “not guilty by reason of insanity.”

The month after he was sentenced to life in prison, DeSalvo and two other convicts escaped from the Bridgewater State Hospital, where he was undergoing mental tests, but they were soon recaptured.

In 1968, George Harrison, DeSalvo’s cellmate and one of the men he had escaped with, said that DeSalvo, rather than being the “Strangler,” had been tutored for the role by another convict. He said he had overheard 15 to 20 conversations between DeSalvo and the other man in Bridgewater.

Mr. Irwin recalled in an interview today that many officers had suspected that DeSalvo had “gleaned the details” of the crimes he had committed from other convicts.

A one-time handyman and boxer, DeSalvo was a big, husky man who wore his black hair slicked back in a pompadour and dressed neatly, typically with a freshly laundered white shirt. He had become skilled in making costume jewelry, and many of his products were on display in the prison lobby.

—November 27, 1973

NOTE: Despite his confession, DeSalvo was never charged with the murders of the 13 women to which he admitted. He was instead tried on other charges, including assault, and sentenced to life in prison, where he was stabbed to death in 1973.

.44 KILLER WOUNDS 12th AND 13th VICTIMS

With massive police patrols focused elsewhere in the city, the killer who calls himself “Son of Sam” shot and critically wounded a young couple early yesterday as they sat in a car parked on the Brooklyn waterfront a mile south of the glittering lights of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

At midafternoon yesterday, more than 12 hours after the shootings, police department ballistics experts confirmed that the attack had been carried out with the same .44-caliber revolver that had been used to kill five young people and wound six others in seven incidents during the last year.

The killer’s strike yesterday had the earmarks of a deadly cat-and-mouse game with the police. It came two days after the anniversary of his first murder, an anniversary marked by increased patrols, wide publicity and spreading public fears. And it came for the first time in Brooklyn, more than 10 miles from his previous attacks, which were clustered in northern Queens and the east Bronx—where the weekend’s patrols were concentrated.

Throughout the weekend in many parts of the city, people warned one another about the killer stalking the streets, seemingly able to strike at will. Such warnings had been made to both of the victims in this, the killer’s eighth attack.

According to witnesses—the police said at least two persons and possibly more saw the attack—the killer this time emerged from the shadows of a nearby park into the faint light of a full moon and walked up behind the couple’s car at Shore Parkway and Bay 14th Street in the Bath Beach section about 2:50 a.m.

The couple, Robert Violante, a 20-year-old clothing-store salesman, of Bensonhurst, and Stacy Moskowitz, 20, a secretary, of Flatbush, were on their first date and had attended a movie before stopping near Dyker Beach Park on a lane known as a local trysting place.

They did not see the gunman approach, but witnesses, including a man who watched it all through the rear-view mirror of his car, said the assailant crouched, aimed with both hands and fired four shots through the open window on the passenger side.

Each victim was shot in the head, Mr. Violante once and Miss Moskowitz twice. Mr. Violante sounded his car horn to attract help and witnesses said he staggered out, screaming: “Help me! Don’t let me die!” The assailant, meantime, was said to have walked away calmly, across a street and into the park, vanishing near the spot where he had appeared.

A police contingency plan dubbed Code 44 was put into effect immediately after the shooting was reported. Police patrols saturated the Bath Beach area and halted lone male motorists, but the effort proved futile.

The victims were taken to Coney Island Hospital and then transferred to Kings County Hospital Center where both underwent extensive operations.

Doctors later said that Miss Moskowitz had suffered brain damage from a bullet that passed through her head and lodged in her neck, and they listed her chances of survival at 50 percent. Mr. Violante’s survival chances were said to be better, but a bullet that passed through his head destroyed his left eye and damaged his right eye, his doctors said.

One bullet fired in the attack had lodged in the car’s steering column, but the fragment was too badly mangled for ballistics experts to say definitely that it had come from the .44-caliber killer’s gun. Not until surgeons removed a nearly whole bullet from Miss Moskowitz’s neck could the police conclusively state that the “Son of Sam” had struck again.

But even before that bullet was analyzed, Chief of Detectives John F. Keenan and other police officials had said they were nearly certain that the attack had been mounted by the psychopath, who has become the object of one of the biggest manhunts in the city’s history.

The pattern of the crime seemed to fit—a gun assault in the early morning hours of a weekend on a young woman with long hair seated in a car with a friend. Specifically, the number of shots fired seemed to fit—“Son of Sam” had, in each of his seven previous assaults, fired four shots from his five-round, .44-caliber Charter Arms Bulldog revolver.

Assailant Fits Description

The description of the assailant also seemed to fit—a man in his 20s, of medium build and dressed in dungarees and a gray shirt with the sleeves rolled up.

In his previous assault, on June 26, the killer shot and wounded another couple sitting in a parked car in Bayside, Queens, after they had left a nearby discotheque. Despite the efforts of a special task force of 70 detectives who have worked on the case full time since April, the police have conceded mounting frustrations and a dearth of leads.

Expectations that the killer would strike again ran high on Friday, the anniversary of the July 29, 1976, killing of 18-year-old Donna Lauria, his first victim, as she sat with a girlfriend in a car in the Bronx.

In one of two taunting notes written in recent months—one to the police and one to Jimmy Breslin, the columnist—the killer asked: “What will you have for July 29? You must not forget Donna Lauria…. She was a very very sweet girl, but Sam’s a thirsty lad and he won’t let me stop killing until he gets his fill of blood.” Amid mounting tensions in the city, many women pinned up their long hair or passed up offers of weekend dates in town, and the police mobilized hundreds of officers in plainclothes for street patrols, and decoy operations focused heavily in areas where the killer had struck before.

The date that was to end in tragedy began, according to the police, with a movie in Brooklyn.

Mr. Violante’s father, Pasquale, said that he had warned his son before the date about the danger of the killer on the loose. “I told him to stay out of Queens,” he said in an interview at Kings County Medical Center. “‘O.K., dad,” he quoted his son as having said. “‘I’ll hang around in Brooklyn.’”

The police said it was uncertain what time the couple had parked at Shore Parkway and Bay 14th Street in Mr. Violante’s brown 1968 Buick. They stopped under a streetlight, and there were other parked cars with couples in the area, a quiet spot with little traffic right off the busy Belt Parkway. A chain-link fence separated the parked couple from a view of Gravesend Bay and the necklace of bridge lights arcing across the Narrows of New York Harbor from Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn to Staten Island.

Miss Moskowitz was shot twice, doctors said later. One bullet grazed the top of her scalp and apparently did not inflict a serious wound. The second crashed into the back of her skull, passed through a portion of her brain and lodged in the back of her neck.

Mr. Violante was struck once by a bullet that entered just behind his left eye, passed above the bridge of the nose and exited above the right eye. The bullet shattered his left eye and inflicted some damage to the right eye.

At Kings County Medical Center, Dr. Jeffrey Freedman, a surgeon who operated on Mr. Violante, declined to offer a prognosis for the right eye, but described Mr. Violante’s condition as “very stable.” After an eight-hour operation, during which the bullet in Miss Moskowitz’s neck was removed along with bone fragments from the brain, her condition was listed as critical.

“Paranoid, Neurotic, Schizoid”

After the assailant’s escape, which was described by witnesses as an almost casual retreat, the police yesterday appeared to be no closer to the identity of the gunman, whom they have called a “paranoid, neurotic, schizoid,” and who seems to hate women.

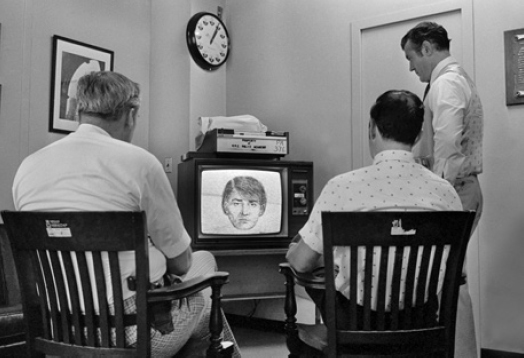

At police headquarters in New York on August 6, 1977, detectives view a composite sketch of the .44 caliber killer, part of a videotape describing the killer and his methods. The tape was played in all 73 precinct houses.

Chief Keenan noted at a news conference that “the witnesses have been very poor, physical evidence is scant and we have no motive.”

A number of bullet fragments, apparently from the slugs that struck the victims with full force, were found in Mr. Violante’s car. One bullet, believed to be the one that had grazed Miss Moskowitz’s scalp, was found lodged and mangled in the steering column and was of little use to ballistics experts the police said.

List of Killer’s Victims

Following is a list of the victims of the killer who calls himself “Son of Sam.”

1. Donna Lauria, 18, of the Westchester Heights section of the Bronx, was shot and killed about 1 a.m. on July 29, 1976, while sitting in a parked car outside her home. Jody Valenti, 19, of Hutchinson River Parkway, was wounded in the left thigh as she sat in the car with Miss Lauria.

2. Carl Denaro, 20, was wounded in the head Oct. 23 as he sat in a parked car with Rosemary Keenan on 160th Street in Flushing, Queens. The injury required doctors to place a steel plate in his skull. Miss Keenan was uninjured.

3. Joanne Lomino, 18, of Bellerose, Queens, was shot in the back of the head at 12:40 a.m. on Nov. 27, 1976, while sitting on the porch of her home with a friend. She is now paralyzed from the waist down. Donna DiMasi, 17, of Floral Park, Queens, was shot through the neck Nov. 27, 1976 while sitting on the porch with Miss Lomino.

4. Christine Freund, 26, of Ridgewood, Queens, was shot to death at 12:30 a.m. last Jan. 30, as she sat in a parked car near the Long Island Rail Road station in Forest Hills, Queens. With her, and unhurt, was John Diel, 30.

5. Virginia Voskerichian, 19, of Forest Hills, Queens, was shot to death at about 7:30 p.m. last March 8 as she walked on Dartmouth Street on her way home from college. She was slain a half block from where Miss Freund was killed five weeks earlier.

6. Valentina Suriani, 18, of Baychester, the Bronx, and Alexander Esau, of West 46th Street, were shot to death at 3 a.m. last April 17 as they sat in a parked car on Hutchinson River Parkway, near Miss Suriani’s home.

7. Judy Placido, 17, of the Pelham Bay section of the Bronx, was shot in the right temple, right shoulder and back of the neck as she sat in a parked car with Salvatore Lupo at 3:20 a.m. on June 26, 1977, in Bayside, Queens. Mr. Lupo, of Maspeth, Queens, was wounded in the right forearm.

8. Robert Violante, 20, of the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn, was shot in the head at 2:50 a.m. yesterday as he sat in a parked car with Stacy Moskowitz in a lovers’ lane area near Dyker Beach Park in the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn. Mr. Violante was critically wounded. Miss Moskowitz, 20, of the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, was shot once in the head and also was critically wounded.

—August 1, 1977

THE SUSPECT IS QUOTED ON KILLINGS: “IT WAS A COMMAND … I HAD A SIGN”

“For more than a year I had been hoping for just one thing—a chance to talk to the ‘Son of Sam,’ a chance to ask him why,” said Det. Gerald Shevlin. He was part of the special homicide task force that had conducted the search for the .44-caliber killer, the largest manhunt in New York’s history.

Just after 3 o’clock yesterday morning, Det. Shevlin had his chance.

Ten detectives who had been assigned to the task force headed by Inspector Timothy Dowd since its formation after the .44-caliber killer claimed his fourth and fifth murder victims in April, crowded into Room 1312 in police headquarters and for a half hour “fired every question we could think of” at the 24-year-old suspect, David Berkowitz of Yonkers.

“From the beginning I had just wanted 10 minutes with him in a motel room so I could find out about the guy I had been hunting for six months,” Det. Shevlin said. “Room 1312 became our motel room. We went in there and wrapped up all the loose ends.”

“Berkowitz was very cooperative,” said Sgt. Joseph Coffey who, with Sgt. Richard Conlon, was directing the questioning. “He was talkative and calm and answered whatever we asked.”

“It Was a Command”

But as task-force members formed a semicircle around the suspect seated in the chief of detectives’ office, an orderly interrogation was abandoned as detectives sought answers to questions they had been pondering for more than a year.

“Why? Why did you kill them?” a detective asked the suspect.

“It was a command,” a detective reported Mr. Berkowitz as responding. “I had a sign and I followed it. Sam told me what to do and I did it.”

Sam, the 24-year-old postal worker explained in a passive voice, is Sam Carr, a neighbor in Yonkers, “who really is a man who lived 6,000 years ago.”

“I got the messages through his dog,” Mr. Berkowitz said. “He told me to kill. Sam is the devil.” Mr. Carr is a neighbor whose dog Mr. Berkowitz is accused of having shot.

At this point, some of the detectives expressed doubt that they were questioning the right man.

“But,” said a detective, “when we asked him about the letter he left after the murder of Valentina Suriani, he knew things that only Sam could have known.”

The suspect was asked how the letter was signed.

“The Monster,” he responded.

“What did you call yourself in the note?”

“The Chubby Behemoth.”

“Did you say anything about Queens?”

“I wrote that Queens girls are prettier.”

Hours later, Inspector Dowd, the commander of the task force, explained the questioning on the letter as detectives gathered around a desk turned into a bar in the chief of detectives’ office:

“It’s because we always knew tonight would come that I never released the first letter to the press,” he said.

David Berkowitz, aka “Son of Sam,” being taken into police custody in New York, August 11, 1977.

Earlier, the detectives had Mr. Berkowitz reconstruct each of the .44-caliber killer’s eight attacks.

The suspect, according to officers at the interrogation, said he was “out driving every night since last July [1976] looking for a sign to kill.”

“The situation would be perfect,” the suspect was quoted as having said. “I would find a parking place for my car right away. It was things like that which convinced me it was commanded.”

Mr. Berkowitz, who said a “‘buddy in Houston” had bought the gun for him, reportedly told the police he had the Charter Arms Bulldog revolver, the .44-caliber weapon the police say was used as the murder weapon, “for about a month” before the first shooting.

As the suspect detailed the attacks, the police learned that many of the theories—and even a few aspects of the investigation that they had accepted as facts—were unsubstantiated. According to detectives, Mr. Berkowitz made the following statements:

• He fired one-handed for the first three attacks, not in the two-hand combat-style position, as the police believed.

• At least twice he fired five times, emptying the .44-caliber revolver. He did not keep one bullet in the chamber, as the police believed.

• He never went inside a discotheque.

• He never wore a wig.

• The attacks were random, his targets always the young girls.

• He insisted he was never jilted by a girlfriend. His only explanation for the attacks was that “they were commanded.”

Never Shot through Bag

Speaking in terse sentences, the suspect explained how he always parked about a block and a half away from the scene of each attack “and then ran like hell to my car.”

He said he had kept his revolver in a plastic bag, but never shot through it as police had theorized.

Why did he carry his gun in a plastic bag?

“I don’t believe in holsters,” the police quoted Mr. Berkowitz as stating with a smirk.

The constant hurling of questions at the suspect was interrupted, however, as Mr. Berkowitz explained what he had planned to do on the night when he was captured.

“I was going out to kill in the Bronx,” he allegedly explained. “I was going to look in Riverdale.”

And then Mr. Berkowitz for the first time posed a question: “Do you know why I had a machine gun with me tonight?”

“I’ll tell you,” he said: “I wanted to get into a shootout. I wanted to get killed, but I wanted to take some cops with me.”

Mr. Berkowitz also told the police how he had visited the sites where he had murdered Donna Lauria, in the Bronx on July 29, 1976, and Christine Freund last Jan. 30 in Forest Hills, Queens, a couple of times after the shootings.

Sought Victim’s Grave

He also went, the detectives related, to St. Raymond’s Cemetery to visit the grave of Miss Lauria, his first victim.

“But,” he said, “the grave was impossible to find.”

Why did he want to go to the grave?

“I felt like it,” Mr. Berkowitz allegedly responded.

“He also told us that the length of hair, the color—all that had nothing to do with his picking out victims,” said, a detective.

In fact, Stacy Moskowitz, the last victim, was not even his target that night, the police reported.

“He had planned to get the girl Tommy Z. was sitting with,” the detective continued, referring to the young man who had witnessed the murder of Miss Moskowitz through his rearview mirror. “But when Tommy Z. moved his car into a darker spot, Berkowitz told us he changed his target.”

Another detective added that Robert Violante, the young man who was seriously wounded when Miss Moskowitz was shot on July 31 in the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn, had told the police about a man who had been sitting on the swings for nearly an hour in the park near when the couple’s car was parked.

“It was while we were questioning Berkowitz that we realized he was the guy on the swings,” the detective explained. “Robert Violante had been staring at the guy who was going to shoot him all night, except he didn’t know it.”

The suspect also answered questions about specific attacks.

Why, he was asked, had he murdered Virginia Voskerichian as she walked home alone from the subway on a Tuesday night? She did not fit into the .44-caliber killer’s pattern.

“It was commanded,” the suspect allegedly replied.

Asked if he had any remorse,” he reportedly said, “No, why should I?”

—August 12, 1977

NOTE: Berkowitz, a 24-year-old postal clerk who said he heard voices that commanded him to kill, confessed to six murders and pleaded guilty. He is serving six consecutive 25-years-to-life sentences in a New York State prison.

SUSPECT IN MASS DEATHS IS PUZZLE TO ALL

In the clean, well-lighted world of middle-class America, the hardworking, outgoing, community-spirited man next door is not supposed to be the suspect in the worst instance of mass killings in the United States in this century.

But John Wayne Gacy is that.

Tomorrow, Mr. Gacy, a short, round, 36-year-old remodeling contractor, is scheduled to appear in a Cook County, Chicago, courtroom for arraignment in a case that may ultimately involve the deaths of at least 32 young men over several years. A grand jury has indicted him in seven murders, and the prosecutors are seeking further indictments as more of the 29 bodies recovered so far are identified.

But who is John Wayne Gacy?

Affable, Driven Businessman

Is he the affable businessman, driven, often boastful, but as eager to please as puppy? The clown, Pogo, who entertained children at picnics and parties? The outgoing man most neighbors, friends and family members knew here, in Springfield, Ill., and in Waterloo, Iowa?

Or is he the night wanderer portrayed by investigators, a man who cruised the homosexual scene’s meanest streets in his black Oldsmobile with police-like spotlights, picking up young male prostitutes or other willing partners? The man who lured youngsters into his contracting business, brutalized them sexually and killed them? The unreformed former convict who served 18 months in an Iowa reformatory after he was convicted in 1968 of having engaged a Waterloo teenager in sodomy?

Or is he both?

A close look at his past does not provide easy answers as to why and how John Gacy became the prime suspect in the bizarre sex murders. Most people who knew him will not discuss him, and those who will seem confused by the charges against him. But a look at Mr. Gacy’s life does provide a picture, puzzling, perhaps even troubling, in its contradictions, of the man who sits quietly in the hospital wing of the Cook County jail awaiting tomorrow’s proceedings.

John Wayne Gacy was born in Edgewater Hospital here in Chicago on March 17, 1942. His parents were John and Marian Gacy, both factory workers, and he grew up with his sisters, one older and one younger, in a working-class neighborhood on the northwest side. His father died nine years ago and his mother, who is 71, lives with his younger sister in Arkansas. The elder sister lives in Chicago. All three family members have desperately sought anonymity. But his younger sister, an articulate, sandy-haired mother of three, agreed to an interview if her identity was not disclosed.

Mug shot of John Wayne Gacy, 1978.

“Just a Normal Person”

“He was a normal person like everyone else,” she said, “just a normal person. My mother just can’t believe it. All she does is cry. I hope people know we’re being torn apart by this.”

The only unusual thing that she could recall about her brother’s younger years, she said, was that he occasionally had blackouts. The problem, she continued, was diagnosed when he was 16 as a blood clot on the brain thought to have resulted from an earlier playground accident.

John Gacy went to Cooley Vocational High School, where he took business courses, his sister said. After a year, he transferred to Prosser Vocational High School, then dropped out after a few months. Later, he attended Northwestern Business College of Chicago.

Visited Once or Twice Yearly

Mr. Gacy’s sister said that he had always been the sort of brother and son who could not do enough for his family, who stayed in close touch by telephone and who visited once or twice a year.

The family knew of his sodomy conviction in Iowa, she said, but considered it “an incident in his life that he paid for.”

Turning to happier memories, such as her brother’s penchant for playing Pogo in clown costumes he had designed for himself, she said that he had always enjoyed entertaining children.

In 1964, shortly before he turned 22, Mr. Gacy, who had been hired by a local shoe company here, was transferred to Springfield as manager of the concern’s retail outlet.

Married Springfield Co-Worker

There he met Marlynn Myers, who also worked at the store. They were married nine months later and moved into the home left behind by his wife’s parents, who had purchased a string of fried chicken franchises in Waterloo.

In Springfield, Mr. Gacy plunged furiously into his job and into community life, joining the Jaycees, a service club. “He was a very bright person, energetic and never displayed any abnormal signs,” recalled Ed McCreight, who worked with Mr. Gacy in the Springfield Jaycees.

Mr. Gacy’s former father-in-law, Fred W. Myers, sold his chicken franchises in Waterloo a year and a half ago and moved back to Springfield. Speaking through the door of his home, open a crack, Mr. Myers said, “I can’t understand why they would have let him out of prison in Iowa.”

In 1966, the Gacys moved to Waterloo, where he helped Mr. Myers manage the fast-food outlets. Mr. Gacy again threw himself into Jaycees’ activities. In 1967, he was vice president of the Waterloo Jaycees, chaplain of the chapter and chairman of its prayer breakfast.

“A Real Go-Getter”

“He was a real go-getter,” said Charles Hill, manager of a Waterloo motel and a friend of Mr. Gacy. “He did a good job and was an excellent Jaycee.”

Others were less receptive to Mr. Gacy’s outgoing ways.

“He was a glad-hander type who would go beyond that,” said Tom Langlas, a lawyer who knew Mr. Gacy through the Jaycees. “He’d shower too much attention on you as a way of getting more attention himself.”

And Peter Burk, a lawyer who opposed Mr. Gacy in 1968 for the local Jaycees presidency, which he subsequently won after Mr. Gacy was charged in the sodomy case, said: “He was not a man tempered by truth. He seemed unaffected when caught in lies.”

In May 1968, two teenage boys told a Black Hawk County grand jury that Mr. Gacy had forced them to commit sexual acts with him.

Youth Said Gacy Chained Him

According to the grand jury records, one of the youths said that Mr. Gacy had chained him and had begun choking him, but that when he stopped resisting his assailant loosened the chains and let him leave.

He was indicted, convicted and sentenced, in December 1968, to 10 years at the state reformatory at Anamosa.

While he was in the reformatory, on Sept. 18, 1969, his wife, Marlynn, was granted a divorce on the grounds of cruel and inhuman treatment and was given custody of their children.

Now remarried, she was reticent about discussing her past with Mr. Gacy, but agreed to an interview if her new name was not divulged.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” she said. “I never had any fear of him. It’s hard for me to relate to these killings. I was never afraid of him.”

No Signs of Homosexuality

She said that she had “problems believing that he was homosexual” at the time of the Iowa sodomy indictment. She said nothing in their married life had indicated that. She added that he had never been violent and that he had been a good father.

At the reformatory in Anamosa, Mr. Gacy is remembered as a model prisoner who headed the Jaycees chapter, worked in the kitchen and was paroled after 18 months.

“He had no particular problem during his stay,” said Warden Calvin Auger. “His adjustment was exceptionally good. He was a good worker, a willing worker with only one minor disciplinary thing on his record, just a hassle with another resident with nobody injured.”

In Des Moines, Donald L. Olson, executive secretary of the Iowa State Board of Parole, which released Mr. Gacy from prison on June 18, 1970, said that the contents of Mr. Gacy’s file were privileged.

“There are psychiatric reports,” he added. “But I can tell you this: If there were any red flags, he wouldn’t have been paroled.”

When Mr. Gacy left the reformatory, he returned to Chicago, where he worked at a restaurant and lived with his mother. After four months in an apartment on the northwest side, he is reported to have borrowed money from his mother to buy his house in Norwood Park Township.

Later, he started his own business, P.D.M. (for painting, decorating and maintenance) Contractors, which he operated out of his home. He specialized in remodeling work at retail stores and subcontracted work on larger construction projects.

Youths Said They Rebuffed Him

Over the years, he hired a succession of youths to work with him. The bodies of two have been identified from among those discovered at his home. Since his arrest, others who worked for him have said that he made sexual overtures toward them, but that they had rebuffed him and he had laughed the matter off.

Meanwhile, the Chicago police have acknowledged that they staked out Mr. Gacy’s home for two weeks in January 1976, when a nine-year-old boy was missing. The police said they questioned a number of young men going in and out of the Gacy home, but none would say anything against him.

No Links Found to Gacy

The police also investigated, in 1975 and in 1976, the separate disappearances of the two youths who had worked for him, but did not turn up anything linking Mr. Gacy to them.

On Dec. 31, 1977, a 19-year-old man charged that Mr. Gacy had kidnapped him at gunpoint and forced him to commit sexual acts, but no criminal charges were filed, according to the police records. The officials said that Mr. Gacy had acknowledged the acts, but had said the man was a willing participant who later tried to blackmail him.

Last March, another young man accused Mr. Gacy of having abducted, chloroformed and raped him. A misdemeanor charge of battery is still pending.

“When these things come up, people say the police should have come up with a pattern,” said David M. Mozee, a spokesman for the police, “but we have a good conscience. We questioned Gacy, we followed Gacy, but we found nothing wrong. We knew of the conviction in Iowa, but that doesn’t make him a mass killer.”

All the while, to his neighbors in Norwood Park Township, he was just the man next door, a trustee of the township’s street lighting district, a Democratic precinct captain, a fun-loving person who gave parties for as many as 400 friends and then shared the leftover liquor and food with those who lived nearby.

In June 1972, Mr. Gacy married Carole Hoff, a divorced woman with two daughters.

Then one time, she said, she found several wallets apparently belonging to teenage boys in his car. He exploded in anger.

“He would throw furniture,” she said. “He broke a lot of my furniture. I think now, if there were murders, some must have taken place when I was in that house.”

The couple was divorced March 2, 1976.

She has said recently on television that he was sexually dysfunctional with women.

Even when he was being followed openly by the Des Plaines police shortly before he was arrested and charged with murder, Mr. Gacy’s neighbors could not believe what was happening.

Sam and Jennie DeLaurentis, who lived across the street, recalled that they had asked him why the police cars were following him all the time. They said he told them that the police were “trying to pin a murder rap on me.” They said he laughed and they laughed.

That was before the police found evidence at Mr. Gacy’s home that Robert Piest, a 15-year-old who disappeared after going to see him on Dec. 11 about a summer job, had been there. The contractor is reported to have told the authorities that he threw the youth’s body into the Des Plaines River.

Since they began digging three days before Christmas, Cook County sheriff’s investigators have dug up 27 decomposed bodies from under Mr. Gacy’s garage and three-bedroom ranch house.

The authorities have said that Mr. Gacy has told them that he killed 32 youths after having sexual relations with them, burying 27 at this home and throwing the bodies of five into the Des Plaines River.

Two bodies have been recovered from the river, making the 29 linked to the case so far the largest number of victims attributed to a murder suspect in the United States in this century.

—January 10, 1979

NOTE: Gacy was convicted of killing 33 young men, many of whom he buried in his home. He was executed in 1994 by lethal injection.

BUNDY IS PUT TO DEATH IN FLORIDA AFTER ADMITTING TRAIL OF KILLINGS

Theodore Bundy, among the most notorious killers in recent times, was electrocuted today, and about 200 people gathered outside the entrance of the Florida State Prison cheered when they heard the news.

He went quietly to his death nearly 15 years after he embarked on a trail of murder that investigators believe took the lives of 30 or more young women across the nation.

“Give my love to my family and friends,” the former law student told his lawyer and a minister as guards strapped him into the wooden chair in an execution chamber separated from two-dozen official witnesses by a large glass window.

He was pronounced dead at 7:16 a.m. after 2,000 volts of electricity surged through his body for one minute, prison officials said.

Outside the prison gates, the crowd cheered and whooped when a signal came from the floodlit cellblock 400 yards away, where the execution took place, that Mr. Bundy was dead.

A few opponents of capital punishment were lost in the crowd that had come in the predawn chill of northern Florida’s piney woods to applaud the death of a man whose “boy-next-door” good looks and intelligence concealed the impulses that led him to hunt down women and murder them.

“Thought He Was So Clever”

“This is a big deal,” said Carey Harper, 26, of nearby Gainesville. “Some of us have waited 11 years for this moment.”

His companion, Jeannine Gordon, 21, expressed a widely held view that reviled not only Mr. Bundy’s murderous acts but also his personal demeanor. “He thought he was so clever, so smart, that he could get away with his crimes,” she said. The execution came on the fourth death warrant signed by a Florida governor. Three of them were issued in 1986, only to be stayed while his appeals were heard in the courts.

The final warrant was for the 1978 murder of Kimberly Leach, a 12-year-old Lake City, Fla., girl who was abducted, mutilated and slain, and whose body was dumped in an abandoned animal pen. He was convicted in 1980 of her killing, a year after he had been found guilty of murdering two Florida State University students who were bludgeoned and strangled as they slept in their beds in a sorority house in Tallahassee three weeks before Kimberly Leach was killed.

Spurt of Confessions

The condemned man spent the last few days confessing at least 16 other killings to police detectives who had come here from the states of Washington, Utah, Idaho and Colorado in an attempt to clear up numerous murder investigations before Mr. Bundy was silenced by his date with the executioner. Some of the confessions were made in killings with which the authorities had not connected him, and federal and state officials still link him to a dozen or more similar crimes since his spree began in February 1974, in Seattle.

Over the years he maintained his innocence, saying he had been drawn into a web of circumstantial evidence woven by “conniving investigators.”

Finally running out of appeals that would be heard by the federal courts, his confidence apparently crumbled. Described as “visibly shaken,” he supplied the detectives with the names of victims in four western states and the dates he killed them.

Florida Department of Corrections mug shot of Ted Bundy, February 13, 1980.

By the time he entered the death chamber shortly before 7 o’clock this morning, he appeared tense but composed, apparently resigned to his fate, according to the witnesses.

One of these, Jerry Blair, was the state prosecutor in the Leach murder trial. Mr. Bundy nodded to him in recognition as he was being strapped into the chair. “I think he was trying to say there were no hard feelings,” Mr. Blair said later. But Mr. Blair and a host of others who had worked on the Bundy crimes over the years, conceded they were no closer now to the central mystery of what had turned a handsome, articulate, urbane young man into one of the most savage and unpredictable killers in the nation’s history.

“Killed for the Sheer Thrill”

“Ted Bundy was a complex man who somewhere along the line went wrong,” Mr. Blair said. “He killed for the sheer thrill of the act and the challenge of escaping his pursuers. He probably could have done anything in life he set his mind to do, but something happened to him and we still don’t know what it was.”

The killer, who stalked victims in the Pacific Northwest in the mid-1970s, terrorized several university communities, selecting coeds for abduction from campuses at night or crowded parks in daytime when their defenses were lowered in familiar settings. Accounts of witnesses and other evidence show that he typically used his good looks and soft-spoken charm to lure them to their death.

He usually throttled them and then sexually abused and mutilated them before disposing of their bodies in remote areas. If the skeletons were found months or years later there was nearly always evidence of fractured skulls and broken jaws and limbs.

“This kind of mutilation reveals a hatred of the female body,” said Dr. David Abrahamsen a New York psychiatrist who is an authority on those who kill people in a series and is author of The Murdering Mind.

“The victim is not really the target,” he said. “The victim is a substitute, and that is why these crimes seem so random and capricious.”

Dr. Abrahamsen theorized that when a man commits a violent sexual crime against an unknown woman, the real motive is rooted in acting out “strong and repeated fantasies of revenge and power” subconsciously directed at his mother.

Mr. Bundy previously hinted that alcohol played a role in his mood swings. On Monday he tearfully told James Dobson, a psychologist and religious broadcaster who served on a federal pornography commission, that hard-core pornography became an obsession and drove him to act out his fantasies in murder.

Boy Scout and B-Plus Student

Theodore Robert Bundy was born to a young, single Philadelphia woman who raised him in Tacoma, Wash. But his mother, Louise Bundy, said there was never a shred of evidence in her son’s first 28 years, before he became a murder suspect for the first time, to hint at any aberrant behavior.

People familiar with his early years say he was a Boy Scout, a B-plus college student; he loved children, read poetry and was a rising figure in Republican politics in Seattle. The year the murders began there he was the assistant director of the Seattle Crime Prevention Advisory Commission and wrote a pamphlet for women on rape prevention.

“If anyone considers me a monster, that’s just something they’ll have to confront in themselves,” he said in a 1986 interview with The New York Times. “For people to want to condemn someone, to dehumanize someone like me is a very popular and effective, understandable way of dealing with a fear and a threat that is incomprehensible.”

—January 25, 1989

JEFFREY DAHMER, MULTIPLE KILLER, IS BLUDGEONED TO DEATH IN PRISON

Jeffrey L. Dahmer, whose gruesome exploits of murder, necrophilia and dismemberment shocked the world in 1991, was attacked and killed today in a Wisconsin prison, where he was serving 15 consecutive life terms.

Mr. Dahmer was 34, older than any of his victims, who ranged in age from 14 to 33. He died of massive head injuries, suffered sometime between 7:50 and 8:10 a.m., when he was found in a pool of blood in a toilet area next to the prison’s gym, said Michael Sullivan, secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

A bloodied broomstick was found nearby, and a fellow inmate who is serving a life sentence for murder, Christopher J. Scarver, 25, of Milwaukee, is the prime suspect, the authorities said.

E. Michael McCann, the Milwaukee County district attorney, who sent Mr. Dahmer to prison in 1992, said, “This is the last sad chapter in a very sad life.”

“Tragically,” Mr. McCann said, “his parents will have to experience the same loss the families of his victims have experienced.”

A third inmate, Jesse Anderson, himself a notorious figure in the history of Milwaukee crime and race, was critically injured in the attack.

Mr. Sullivan would not comment on a possible motive for the beatings. Mr. Scarver, who is black, was convicted in 1992 of murdering Steve Lohman, who was shot in the head at the Milwaukee office of the Wisconsin Conservation Corps, where he worked, officials said. Mr. Scarver is not eligible for parole until 2042.

But both Mr. Dahmer, whose victims were mostly black, Hispanic and Asian men and boys, and Mr. Anderson, a white man who killed his wife and blamed it on two black men, had badly shaken Milwaukee’s racial peace.

Mr. Dahmer and the two other inmates had been assigned to clean the toilets and the showers near the gym and had arrived there under guard at 7:50 a.m. Then the inmates were apparently left unattended for up to 20 minutes.

“They followed procedures,” Mr. Sullivan said of the guards. “There was no irregular gap in supervision.”

The three inmates, all convicted murderers, had been on the routine work detail together for three weeks without incident—until today. At 8:10 a.m., a guard returned to find Mr. Dahmer bleeding on the floor. The guard sounded the alarm and then found Mr. Anderson several rooms away in the shower area.

When Mr. Dahmer arrived at the prison, the Columbia Correctional Institute in Portage, about 40 miles north of Madison, his safety was a major concern.

The blond former chocolate-factory worker was the most prolific killer in the state’s history, so, the authorities feared, killing him might earn a convict an honored place in the prison world, especially for someone with a long sentence and with little to lose.

Mr. Dahmer’s first year in prison had been spent in protective isolation, away from the general inmate population. But in the last year, Mr. Dahmer and the prison authorities had deemed it safe for him to be integrated into the general population of 622 inmates.

Last July, however, an inmate tried to slash Mr. Dahmer’s throat with a plastic homemade knife during a chapel service. Mr. Dahmer was not injured and it was determined that the attack was an isolated incident.

“He never told me he was afraid,” said Stephen Eisenberg, a lawyer representing Mr. Dahmer in several civil suits filed by the families of his victims. Mr. Dahmer confessed to 17 killings, 16 in Wisconsin and one, his first, he said, in his hometown of Bath Township, Ohio, a suburb of Akron. He pleaded guilty and was convicted of 15 killings in Wisconsin. Prosecutors said there was not enough evidence to charge Mr. Dahmer with the 16th slaying.

Mr. Dahmer also pleaded guilty to the Ohio slaying of a young hitchhiker, Steven Hicks, in his parent’s home in 1978.

Mr. Dahmer met most of his victims at bus stops, bars, malls and adult bookstores in Chicago and Milwaukee. He then lured them to his apartment in a hard-pressed section of Milwaukee with promises of beer or money in exchange for posing for nude photographs. Then he would drug their drinks, strangle and stab them while they were unconscious. He ate part of the arm of at least one man and stored the remains, including the hearts, of several others in his refrigerator.

Mr. Dahmer told investigators he killed to ward off loneliness. “I didn’t want them to leave,” he said.

Mr. Dahmer was almost caught in May 1991 when a 14-year-old Laotian boy, Konerak Sinthasomphone, stumbled into the street bleeding when Mr. Dahmer left the apartment for a six-pack of beer. Two Milwaukee police officers ignored the pleas of a woman who said the boy was in trouble, and allowed Mr. Dahmer to take him back into his apartment, apparently believing Mr. Dahmer’s story that he and the boy were lovers after a spat.

Mr. Dahmer later told investigators that shortly after he got the boy back into his apartment, he killed him. After the Dahmer case broke, the two officers who found the boy bleeding were dismissed, but they won reinstatement last April after a lengthy court battle. One has since left the department.

Mr. Dahmer was finally arrested after another intended victim broke free and ran into the street with a handcuff dangling from his wrist.

While Mr. Dahmer is now dead, the legal battle over his estate remains alive. Several families of his victims sued him and were awarded millions of dollars. Ever since, they have been trying to gain control of the contents of his Milwaukee apartment, where he killed most of his victims.

The families want to auction off some 312 items, including a 55-gallon vat he used to decompose the bodies, the refrigerator where he stored hearts, a saw, a hammer and his toothbrush. Tom Jacobson, the lawyer for the families, said the auction could bring more than $100,000.

Rita Isbell, the sister of one of Mr. Dahmer’s last victims, Errol Lindsey, 19, said she always knew that this day would come sooner or later. For the past two years, she said, she has been getting telephone calls from men identifying themselves as prison inmates, offering condolences and promises that Mr. Dahmer would be “taken care of.” The last call came about six months ago.

“You don’t know me,” Ms. Isbell quoted the caller as saying. “I’m up here with Jeffrey Dahmer. Don’t worry. We’ll take care of it.”’

—November 29, 1994

RETRACING A TRAIL: THE SNIPER SUSPECTS; SERIAL KILLING’S SQUAREST PEGS: NOT SOLO, WHITE, PSYCHOSEXUAL OR PICKY

The middle-aged man and the teenager were footloose traveling companions on a fathomless mission of horror. For three weeks, investigators say, they killed—callously, wantonly, ceaselessly, driven by a logic known only to themselves—and thus qualified themselves for inclusion in the macabre fraternity of the serial killer.

When the police captured a slumbering John Allen Muhammad, a 41-year-old army veteran and expert marksman, and John Lee [Lee Boyd] Malvo, a 17-year-old Jamaican citizen, at a highway rest stop early Thursday morning, the authorities declared an end to the sniper shootings that left 10 people dead and millions panic-stricken in the Washington, D.C., suburbs.

If the men are convicted, they will add a highly peculiar chapter to the already saturated history of the multiple killer. If anything is clear in that roll call of malevolence, it is that all serial killers are their own story, with their own idiosyncrasies and twisting plot lines, their own tumble of complexities. The only true common denominator among them is skill at bringing about death.

But as criminologists and academicians try to find the proper context for the sniper suspects, they have been struck by how unconventional the pair appear to be. In many ways, based on the still sketchy information known about them, they seem to defy the broad connections that have been drawn among their criminal predecessors.

“This is certainly out of the realm of what I’ve seen in the past,” said Peter Smerick, a former agent and criminal profiler with the FBI now in private practice with the Academy Group, a forensic science–consulting firm. “Of all the thousands of cases I’ve analyzed, I haven’t seen one exactly like this one.”

The Team Killer

The fact that there are two of them sets them apart. Serial killers are usually loners, who strike without accomplices or companions, propelled by their personal demons and objectives.

It is unclear whether both Mr. Muhammad and Mr. Malvo actually killed, but investigators say they traveled together in the three weeks of the shootings.

Several experts estimate that no more than 10 to 28 percent of serial killers are teams, although some of the pairs qualify as among the most infamous of all criminals. The Hillside Strangler, for instance, was actually two cousins, Angelo Buono Jr. and Kenneth Bianchi, who were convicted of kidnapping, raping, torturing and murdering young women in Los Angeles in the late 1970s.

In team killings, according to students of serial killers, one member usually dominates.

“Typically, what you have is a dominant offender who is the driving force and the second individual is usually more subservient,” said Gregg McCrary, who for 25 years worked in the FBI’s behavioral sciences unit. “Rarely are they real peers.”

Mr. Muhammad seemed to hold considerable sway over Mr. Malvo. Though apparently unrelated, Mr. Malvo called Mr. Muhammad father and is said to have adhered to a rigid diet of crackers, honey and vitamin supplements he insisted upon. Even among teams, though, the sniper suspects were unusual because of the 24-year disparity in their ages.

The Race Factor

He would be white. That was the consensus of many experts who furnished educated guesses on the sniper’s identity before the arrests. Serial killing, they said, was a white man’s game.

Both suspects are black.