CHAPTER 11

WHITE COLLAR

“Sentence this monster named Madoff to the most severe punishment within your abilities. We are too old to make up what we lost. We have to start over.”

—Randy Baird, an investor and victim of Bernard Madoff’s fraud, in a 2009 letter to Judge Denny Chin

Though typically obscured by the complexities of commerce and buried in layers of phony paperwork, few crimes have wider impact than financial frauds. They often erase a lifetime of savings. More broadly, they cripple the investor confidence on which our economic system relies. For decades, The Times has been helping readers untangle the myriad schemes that put them at risk, from the wizardry of Charles Ponzi to the flimflams of Bernie Madoff.

EXCHANGE “WIZARD” IS PAYING CLAIMS

Charles Ponzi, head of the Securities Exchange Company, began today to pay in full all matured claims against him and the investments of all who wanted their money back, following his announcement yesterday that he had suspended operations in international exchange, by which he claims to have made several million dollars within a few months.

Meanwhile, an application was made by one of Ponzi’s creditors in the superior court today for a receivership for the Ponzi concern, and a temporary injunction restraining Ponzi from drawing on funds on deposit in several banks here in Boston.

Judge Wait declined to grant the temporary injunction, and the application for a receivership was withdrawn.

Judge Wait’s decision to withhold temporary action against the firm followed a statement by Samuel L. Ballen, appearing for Ponzi, that Ponzi and his firm are meeting all obligations, and that Ponzi declares his ability to meet them in full.

Secret selection of an auditor to investigate the affairs of Ponzi, the newest “financial wizard,” whose promise to “double your money within 90 days” has set Boston wild: a near riot in the School Street offices of the Securities Company, in which four women were exhausted by hours of frantic endeavors to reach the inner offices to collect their money during one of the periodic attempts of the crowd to force entrance to the rooms; the injury to several men in the crowd who were cut by flying glass from the doors when they attempted to force their way inside; and a constantly growing demand for repayments of credits, marked the day’s developments in the $8,500,000 financial sensation.

District Attorney Joseph C. Pelletier announced today that he had appointed an auditor to examine carefully the standing of Ponzi’s business venture. Pelletier refused to answer any questions as to why he concealed the name of the auditor, or to speculate or comment in any way upon the case.

Shortly before the announcement, a crowd of persons who had invested money with Ponzi, most of whom were Italians from the North End colony, rushed his offices, forced admittance, and gave the police a merry time before order was restored.

A second disturbance occurred during the luncheon hour when a flying wedge of creditors jammed the doors of Ponzi’s office. So many creditors appeared at the School Street offices that Ponzi took over the Bell-in-Hand, famous for years as a barroom in Pie Alley, and transformed the place into a temporary office. There applicants for return of loans were received, their applicants checked, and those approved paid from a hastily constructed cashier’s booth.

At least a thousand claims were settled today before the business closed, actual cash on hand in Ponzi’s offices had been exhausted, and clerks were giving out bank checks. At the close of business this afternoon, Ponzi gave out a statement to the press that said that, in accordance with an agreement he had made with the district attorney, he had paid “every obligation presented at my office today in the form of notes issued by me during the past 45 days. “The amount paid out by me during the day amounted to several hundred thousands of dollars. I shall continue every day until all of my obligations have been presented.”

Ponzi Tells His Methods

U.S. District Attorney Daniel J. Gallagher today issued the following statement as coming from Ponzi, in which Ponzi himself explained the methods he was using to double money with 90 days:

“The method is the conversion of American money, first into depreciated foreign currency, no matter what it is; or the conversion of foreign money, not depreciated, into foreign money that is depreciated. I am making this statement because I do not actually send money abroad, but I use funds I have abroad between one country and another. That is the first part of the transaction.

“The second part is the purchasing of the depreciated currency in international reply coupons.

“The third part is the reduction of these international reply coupons in countries in which the currency is not depreciated, and the conversion, of course, into postage stamps.

“The fourth part is the disposal of the postage stamps, and the fifth is either the conversion of the money that I derive the sale of the stamps into American money, or the credit of such money into some foreign money to have at my disposal to repeat the operation.”

Continuing, Mr. Gallagher’s statement said:

“Mr. Ponzi said he has in the United States upward of $5,000,000 and between $8,000,000 and $99,000,000 in depositories abroad. He was asked why it was that, having eight or nine millions of dollars in American money, he should maintain an office here to solicit and receive more money, or why he should pay agents a commission for soliciting people to invest. He said he did not use the money, but that he would eventually need the people.

“When asked for what purpose he would need the people he said it was possible that he might want to run for office. On being asked if he was a citizen of the United States, he replied, ‘almost.’ On being asked if his international reply coupon enterprise was a preliminary to something bigger, he answered, ‘Very much so.’

“He said he was going to start a different banking system, that instead of giving the net profits entirely to stockholders the net profits would be divided equally between the stockholders and the depositors, because the stockholders are taking the depositors’ money and paying the depositors only 5 percent. He declared he would make Boston the largest importing and exporting center in the United States and that his present enterprise was only preliminary to that end. He said that he needed popularity and if he made $100,000,000 he would keep $1,000,000 and spend the other $9,000,000 in charitable work or something that would do good for the people.

“‘Today,’ said Mr. Ponzi, ‘that official would be tickled to death if he had put in $5,000, and he is not the only one.’

“To all intents the business has been based upon the wide variation in the rates of foreign exchange. Ponzi, according to his explanations, took advantage of the discrepancies in the money rates through the medium of the international postal reply coupon. These coupons have constant value throughout the countries in the international postal agreement. A coupon worth three two-cent stamps here is worth stamps to equal value in Bulgaria, or any of the other countries, but coupons in Bulgaria, where the money rate is low, are at a discount. The same amount of American money will buy more value in coupons in Bulgaria than in the United States.

“Ponzi had agents throughout Europe, he maintains. These bought coupons where they were cheap. The coupons were taken to countries where money rates were high and converted into stamps. These stamps were sold to big business houses or other large users, Ponzi said.

“The official U.S. Postal Guide sets forth the details of how international reply coupons were to be used. They were intended merely as a business convenience, but it seems that Ponzi was the first one to conceive how they could be exploited.

“His customers did not invest directly in these coupons. They simply deposited their money with him and took in return a note for one and one-half times the amount, redeemable in 90 days. He was offering interest in investments at the rate of 200 percent annually, and in many cases he was actually giving returns at a far greater rate.”

Washington Is Puzzled

Washington, July 27—Postal authorities are investigating closely the manipulations whereby Charles Ponzi, of Boston, says he has made millions out of dealings in “international reply coupons.” The post office officials said today they were going into every angle of the affair.

From all that can be gathered, it appears that the Ponzi story has the authorities here puzzled. One thing is said to be certain, and that is, if the promoter is not engaged in an enterprise entirely within the law, he will be barred from the mails, and perhaps prosecuted.

Officials here say that no great increase in the sale of international reply coupons has been shown, as would be the case if Ponzi’s agents abroad had purchased them wholesale.

Charles Ponzi in Italy, 1935.

The statements from Boston that Charles Ponzi, head of the Securities Exchange Company there, had made more than $8,000,000 by manipulating international postal reply coupons was characterized as “impossible” by postal authorities here yesterday. The coupons are only worth five cents a piece when redeemed, it was pointed out, and the total number sold in 1919 throughout the country amounted only to $1,819.00

—July 27, 1920

NOTE: Ponzi was convicted of mail fraud in 1920 and served three and half years in federal prison. After his release, he was convicted of larceny in Massachusetts and imprisoned there until 1934, when he was deported to Italy. He moved to Brazil before the outbreak of World War II and died a pauper in Rio de Janeiro in 1949.

VAN DOREN PLEADS GUILTY; IS FREED

Charles Van Doren and nine other former contestants on rigged television quiz shows pleaded guilty yesterday in New York to perjury charges and received suspended sentences from Justice Edward F. Breslin, who said the humiliation was evident in their faces. The court could have imposed prison terms up to three years along with fines of $500 on each. The defendants had been among 20 persons accused of second-degree perjury, a misdemeanor, in telling a grand jury they had not been coached on questions and answers prior to appearing on such television shows as Twenty-One and Tic Tac Dough.

Yesterday morning, they changed earlier not-guilty pleas to guilty.

Besides Mr. Van Doren, 35, who won $129,000 on Twenty-One, those entering guilty pleas included Miss Elfrida Von Nardroff, who won the record amount of $220,500 on the show, and Hank Bloomgarden, who won $98,500.

Justice Notes Humiliation

Assistant District Attorney Joseph Stone read the charges against Mr. Van Doren, a former instructor at Columbia University and a member of a distinguished literary family, who appeared gaunt and nervous. Then, in a loud, clear voice, he replied, “Guilty.” “How deep and how acute your humiliation has been is quite evident,” said Justice Breslin. “I have seen it on your face and on the faces of other defendants in this case.”

Charles Van Doren, shown in profile at center right, at a news conference in New York in October 1959, several weeks before his appearance at a congressional investigation committee in Washington.

The justice continued: “I understand that you were one of the first who wanted to throw himself on the mercy of the court. The punishment began the day the matter was exposed to the press and not the day you went before the grand jury.

“This is your first offense, and you are entitled to a chance.”

Defendants Nervous

The courtroom was tense as each defendant appeared before the bench. All the contestants seemed nervous and contrite. Each pleaded guilty in a low voice, some almost in whispers.

The 10 defendants brought to 17 the number of former TV contestants who have pleaded guilty and received suspended sentences. Another received youthful offender treatment. A 19th has never been named because of being outside the court’s jurisdiction, and the 20th, Mrs. Ruth Klein, 30, a housewife, had her case put over until next Wednesday because her lawyer was hospitalized.

So far as is known, there has been no indication that any of the contest winners have returned the money received from a fixed program.

Mr. Van Doren, who was accompanied by his wife, Geraldine, spoke outside in the corridor. He said he had not been working regularly recently but had received several job offers.

“I’d like to drop out of the limelight altogether and get back to teaching,” he said.

Asked if he had learned any moral from his experience, he replied:

“That’s for you to say. All I want to do is just go home and try to forget the whole thing.”

Late in 1958, Mr. Van Doren denied he had received advance answers to difficult questions on the quiz show. But a year later he appeared before a congressional investigation committee in Washington and admitted he had been coached in his replies. After a second grand jury inquiry, he was charged with perjury along with other contestants.

—January 18, 1962

MILKEN GETS 10 YEARS FOR WALL ST. CRIMES

Michael R. Milken, the once-powerful financier who came to symbolize a decade of excess, was sentenced to 10 years in prison yesterday for violating federal securities laws and committing other crimes.

The sentence, handed down by Federal District Judge Kimba M. Wood in Manhattan, was the longest received by any executive caught up in the Wall Street scandals that began to unfold in 1986. But Judge Wood left open the possibility that Mr. Milken could be eligible for parole at any time during his sentence and that his sentence could be reduced if he cooperated in future investigations. Some legal experts said they did not expect him to be paroled until he served at least a third of the prison term.

After Mr. Milken serves his term, he faces a three-year period of probation. Mr. Milken, who paid $600 million in fines and restitution when he pleaded guilty to the violations, will also be required to perform 1,800 hours of community service during each of three years of probation.

Judge Wood said the former financier had to be sentenced to a long jail term to send a message to the financial community, and because he chose to break the law despite his advantages of position and intelligence.

“When a man of your power in the financial world, at the head of the most important department of one of the most important investment banking houses in this country, repeatedly conspires to violate, and violates, securities and tax laws in order to achieve more power and wealth for himself and his wealthy clients, and commits financial crimes that are particularly hard to detect, a significant prison term is required,” she said.

A Lengthy Investigation

The sentencing of Mr. Milken closes the most significant chapter of the longest investigation ever of crime on Wall Street. Over four years, numerous top Wall Street executives confessed to criminal activities and testified for the government. But Mr. Milken did not cooperate with the inquiry and admitted his guilt only last April.

As head of the “junk bond” operations of Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc., which collapsed earlier this year, Mr. Milken financed some of the largest corporate takeovers in the 1980s. He pioneered the use of high-yield, high-risk junk bonds as instruments for corporate warfare, convincing investors that the bonds’ high returns more than compensated for the risk that the issuers would default.

The sentence came at the end of an emotional hearing, in which Mr. Milken frequently broke into tears as he listened to one of his lawyers plead for leniency.

Mr. Milken made only one comment during the proceeding, tearfully telling Judge Wood: “What I did violated not just the law but all of my principles and values. I deeply regret it, and will for the rest of my life. I am truly sorry.”

Mr. Milken did not flinch when the sentence was handed down, but his lawyers and family seemed momentarily stunned by the sentence.

When the hearing ended, Mr. Milken’s wife, Lori, and other family members came to his side. They quickly left the courtroom, and cries of sorrow were heard inside the court after the door closed behind them.

One Lawyer’s Reaction

Lawyers and legal experts also expressed surprise. “This is an incredibly long sentence,” said Michael Feldberg, a partner at Shea & Gould. “If there is a message to be gained from this experience, it is, at least for this judge, cooperation is enormously important.”

In his settlement, Mr. Milken had agreed to respond truthfully to any questions asked him by the government after he is sentenced. Judge Wood said that if that testimony proves to be valuable in future investigations, she would consider reducing the sentence. Judge Wood said yesterday that although she did not accept that Mr. Milken committed insider trading or manipulated a particular security, as the government tried to prove, she believed that the former financier had tried to prevent investigators from uncovering his crimes by suggesting to subordinates that they dispose of important documents.

Some See Vindication

Government officials indicated that the sentence was a vindication of the four-year inquiry into Mr. Milken’s practices in the financial markets.

“This sentence should send the message that criminal misconduct in our financial markets will not be tolerated, regardless of one’s wealth or power,” said Richard C. Breeden, the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Mr. Milken agreed to plead guilty in April to six felonies. He admitted to a conspiracy between himself and two clients, Ivan F. Boesky and David Solomon, the manager of an investment fund. Mr. Milken pleaded guilty to hiding stock for Mr. Boesky to allow the speculator to file false information with the government, and at another time to allow him to avoid minimum capital requirements for a stock-trading firm.

28 Years Was Possible

Mr. Milken had faced a maximum of 28 years in prison, but few legal experts were estimating that his sentence would exceed eight years.

Mr. Milken’s lawyer, Arthur L. Liman, had asked Judge Wood to sentence his client only to a term of community service.

Mr. Liman repeatedly stressed that his client was not a criminal on a par with Mr. Boesky, the stock speculator whose settlement of insider trading charges in 1986 and subsequent cooperation with the government helped expose the Wall Street scandals.

“Two conflicting pictures have been presented of Michael Milken,” Mr. Liman said. “The government, which has not spent time with him, tries to cast him in the Boesky mold, but I would say to Your Honor that that template does not fit.”

Mr. Boesky, who pleaded guilty to filing a false statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, was sentenced in 1987 to three years in prison. He was released on parole this year.

Charitable Work Described

Mr. Liman described Mr. Milken’s philanthropic works. He said Mr. Milken had contributed more than $360 million to charity, and Mr. Liman read numerous letters from people who said they had been personally helped by the financier.

During the reading of the first of those letters, from a mother whose child was injured in an accident, Mr. Milken began to sob quietly.

Mr. Liman added that he could not explain why his client had committed his crimes. “I am not a psychiatrist,” he said. “I have worked very closely with Michael, and I can’t offer an explanation as to how Michael slipped.”

In his response, Jess Fardella, an assistant U.S. attorney, said Mr. Milken was a brilliant and decent man, but added that because of that, his crimes should be judged in a harsher light.

The Government’s Viewpoint

That perspective, Mr. Fardella said, showed that Mr. Milken had abused his advantages and his position for personal benefit. “That the defendant was blessed with intelligence, energy, education and the support of family and friends makes his choice to engage in persistent violations of the law all the more inexcusable,” he said. “Despite his talents and opportunities, Mr. Milken sought to multiply his success through the vehicle of criminal fraud.”

Mr. Milken is acknowledged to be the highest-paid financier ever; he took home $550 million in compensation from Drexel in 1987 alone. Yet Mr. Fardella said the financier committed his crimes out of desire for more money.

The prosecutor also argued that Mr. Milken’s crimes should not be taken lightly just because there was not an immediately apparent victim.

“Such deceptive and unlawful practices inevitably have a corrosive effect on these markets,” Mr. Fardella said. “Left unchecked and unpunished, they threaten the entire process of savings and capital formation.”

The Deterrence Factor

Mr. Fardella also asked Judge Wood to consider the importance of sending a message to the financial community that would deter other criminal conduct.

In describing her reasoning, Judge Wood said yesterday that she did not find the government’s portrayal of Mr. Milken as “one of the most villainous criminals Wall Street ever produced” to be persuasive. But she also said she did not accept the defense position that Mr. Milken’s crimes were aberrations in which he went beyond the law to help a client.

“Your crimes show a pattern of skirting the law,” she said, “stepping just over to the wrong side of the law in an apparent effort to get some of the benefits of violating the law without running a substantial risk of being caught.”

Immediately before sentencing Mr. Milken, Judge Wood praised him for his generous nature, adding that she hoped he would continue on that path.

“You are unquestionably a man of talent and industry and you have consistently shown a dedication to those less fortunate than you,” the judge said. “It is my hope that the rest of your life you will fulfill the promise shown early in your career.”

—November 22, 1990

NOTE: A judge later reduced Milken’s sentence to two years. Barred for life from the securities industry, Milken turned his focus to philanthropy. Today his foundations support educational programs and medical research.

2 ENRON CHIEFS ARE CONVICTED IN FRAUD AND CONSPIRACY TRIAL

Kenneth L. Lay and Jeffrey K. Skilling, the chief executives who guided Enron through its spectacular rise and even more stunning fall, were found guilty Thursday of fraud and conspiracy. They are among the most prominent corporate leaders convicted in the parade of scandals that marked the get-rich-quick excesses and management failures of the 1990s.

The Houston jury reached the verdicts after just over five days of deliberations. Mr. Skilling was convicted of 18 counts of fraud and conspiracy and one count of insider trading. He was acquitted on nine counts of insider trading. Mr. Lay was found guilty on six counts of fraud and conspiracy and four counts of bank fraud.

The conspiracy and fraud convictions each carry a sentence of 5 to 10 years in prison. The insider trading charge against Mr. Skilling carries a maximum of 10 years.

“The jury has spoken and they have sent an unmistakable message to boardrooms across the country that you can’t lie to shareholders, you can’t put yourself in front of your employees’ interests, and no matter how rich and powerful you are you have to play by the rules,” Sean M. Berkowitz, the director of the Justice Department Enron Task Force, said outside the courthouse.

Both men are expected to appeal. Judge Simeon T. Lake III, the judge in the case, set sentencing for Sept. 11. Until then, the two men are free on bail. If they lose their appeals, Mr. Skilling and Mr. Lay face potential sentences that experts say could keep them in prison for the rest of their lives. “Obviously, I’m disappointed,” Mr. Skilling said as he left the courthouse, “but that’s the way the system works.”

Once jurors and the judge cleared out of the courtroom, Mr. Lay’s family members huddled around him. Elizabeth Vittor, Mr. Lay’s daughter and a lawyer who had worked on his defense team, sobbed. After he emerged from court, Mr. Lay said, “I firmly believe I’m innocent of the charges against me.”

For a company that once seemed so complex that almost no one could understand how it actually made its money, the cases ended up being simpler than most people envisioned. Mr. Lay, 64, and Mr. Skilling, 52, were found guilty of lying—to investors, employees and regulators—in an effort to disguise the crumbling fortunes of their energy empire.

The 12 jurors and three alternates, who talked to reporters at a news conference after the verdict, said they were persuaded—by the volume of evidence the government presented and by Mr. Skilling’s and Mr. Lay’s own appearances on the stand—that the men had perpetuated a far-reaching fraud by lying to investors and employees about Enron’s performance.

The panel rejected the former chief executives’ insistence that no fraud occurred at Enron other than that committed by a few underlings who stole millions in secret side deals. For years, Enron’s gravity-defying stock price made it a Wall Street darling and an icon of the “New Economy” of the 1990s. But its sudden collapse at the end of 2001 and revelation as little more than a house of cards left Enron the premier public symbol of corporate ignominy. Investors and employees lost billions when Enron shares became worthless.

Enron’s fall had a far greater impact than on just the energy industry by heightening nervousness among average investors about the transparency of American companies. “The Enron case and all the other scandals and cases that trailed after it may have finally punctured that romance with Wall Street that has been true of American culture for a while now,” said Steve Fraser, a historian and author of Every Man a Speculator: A History of Wall Street in American Life.

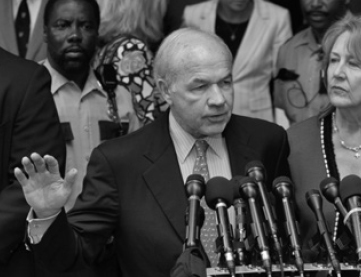

Former Enron Corp. executive Kenneth L. Lay speaks to the media outside the Bob Casey Federal Courthouse in Houston, Texas, Thursday, May 25, 2006.

At Enron, Mr. Skilling was the visionary from the world of management consulting who spearheaded the company’s rapid ascent by fastening on new ways to turn commodities, like natural gas and electricity, into lucrative financial instruments.

Mr. Lay, the company’s founder, was Enron’s public face. Known for his close ties to President Bush’s family, he built Enron into a symbol of civic pride and envy here in its hometown of Houston and throughout the financial world.

The verdicts are a vindication for federal prosecutors, who had produced mixed results from their four-year investigation of wrongdoing at the company. The investigation resulted in 16 guilty pleas by Enron executives, and four convictions of Merrill Lynch bankers in a case involving the bogus sale of Nigerian barges to the Wall Street firm.

Last year, however, the Supreme Court overturned the obstruction-of-justice verdict that sounded the death knell for the accounting firm Arthur Andersen, Enron’s outside auditor. And a jury either acquitted or failed to agree on charges in the fraud trial of former managers of Enron’s failed broadband division.

In the 56-day trial, defense lawyers repeatedly criticized prosecutors for bringing criminal charges against Mr. Skilling and Mr. Lay, saying the government had set out to punish the company’s top officers regardless of what the facts might be. The lawyers said the government was criminalizing normal business practices and accused prosecutors of pressuring critical witnesses to plead guilty to crimes they did not commit.

The defense lawyers also complained about a lack of access to witnesses who they contended could have corroborated their clients’ versions of events. Several jurors said they would have liked to hear from more witnesses, in particular Richard A. Causey, the chief accounting officer, whom neither side called. The Enron trial, more than any other, punctuates the era of corporate corruption defined by the failure of WorldCom, the telecommunications giant whose bankruptcy following revelations of $11 billion in accounting fraud exceeded even Enron’s in size; the prosecution of Frank P. Quattrone, the technology industry banker; and scandals at Tyco, Adelphia and HealthSouth.

From the beginning, the Enron leaders’ trial was not what many people expected after revelations of secret off-the-books schemes that earned a small fortune for Andrew S. Fastow, Enron’s former chief financial officer, and his co-conspirators. Some of those transactions were used by Mr. Fastow without approval by anyone to enrich himself at Enron’s expense; others were used to manipulate Enron’s financial reports with what Mr. Fastow testified was the full knowledge of his bosses. Rather than delve into those intricate structures, prosecutors focused on what they cited as the false statements Mr. Skilling and Mr. Lay made to employees and outside investors.

The “lies and choices” theme transformed the case into a test of credibility between the former chief executives and the more than half a dozen witnesses from inside Enron who testified for the government.

During the trial, the government called 25 witnesses and the defense called 31, including Mr. Skilling and Mr. Lay. Government witnesses, including the former Enron treasurer, Ben F. Glisan Jr., testified that the executives had sanctioned or encouraged manipulative accounting practices and crossed the line from cheerleading into outright misrepresentations of financial performance.

Mr. Fastow’s emotional turn on the stand offered some of the most devastating evidence against Mr. Skilling, and to a lesser extent, Mr. Lay. He said he had struck “bear hug” side deals with Mr. Skilling guaranteeing that his off-the-books partnerships, called LJM, would not lose money in their dealings with Enron. Mr. Fastow also described how Mr. Skilling had bought into using the LJM’s to bolster earnings.

But Mr. Fastow’s own admitted history of extensive crimes at Enron was dissected by Skilling’s lead lawyer, Daniel Petrocelli, and jurors said they did not find Mr. Fastow particularly persuasive. “Fastow was Fastow,” said a juror, Donald Martin. “We knew where he was coming from.”

The jurors said they were moved, in contrast, by the testimony of Mr. Glisan. “We kept on going back to that testimony to corroborate things,” said one juror, Freddy Delgado, a school principal.

The surprise testimony of David W. Delainey, the former chief of a retail unit called Energy Services, also helped pave the way for Mr. Skilling’s conviction. Mr. Delainey, who pleaded guilty to fraud, said that Mr. Skilling took part in a decision to shift $200 million in losses from Energy Services to the more profitable wholesale energy division to avoid having to admit to investors that Energy Services was failing.

On the stand, Mr. Skilling offered differing and confusing explanations for the shift, and proved evasive and sometimes forgetful.

His resignation in August 2001, after only six months as chief executive, led to a bout of heavy drinking as a depressed Mr. Skilling watched in horror as the company he helped build edged closer to the brink.

For Mr. Lay, a turning point came when Sherron S. Watkins, the former Enron vice president, took the stand to describe how she confronted him with concerns about Enron’s accounting. Ms. Watkins suggested that the subsequent investigation Mr. Lay ordered was intentionally limited in scope to conclude that there were no problems.

Other issues plagued Mr. Lay’s defense, notably his own testiness on the stand and the sudden illness of his lead lawyer, Michael W. Ramsey, a well-regarded criminal defense lawyer who was forced to miss more than a month of the trial because of coronary disease that required two operations. Mr. Lay decided to carry on without Mr. Ramsey rather than seek to delay the trial and fight another day.

—May 26, 2006

NOTE: Lay died of a heart attack six weeks after the verdict. A federal judge vacated Lay’s conviction on the grounds that he could no longer appeal, thereby thwarting the government’s plan to seize more than $43.5 million from Lay’s estate. Skilling was sentenced to 24 years, but the sentence was trimmed by 10 years in 2013.

MADOFF GOES TO JAIL AFTER GUILTY PLEAS

When Bernard L. Madoff entered a federal courtroom in Manhattan on Thursday to admit that he had run a vast Ponzi scheme that robbed thousands of investors of their life savings, he was as elegantly dressed as ever. But, preparing for jail, he wore no wedding ring—only the shadowy imprint remained of one he has worn for nearly 50 years.

He admitted his guilt for the first time in public, and apologized to his victims, dozens of whom were squeezed into the courtroom behind him, before being handcuffed and led away to jail to await sentencing.

“I knew what I was doing was wrong, indeed criminal,” he said. “When I began the Ponzi scheme, I believed it would end shortly and I would be able to extricate myself and my clients.”

But finding an exit “proved difficult, and ultimately impossible,” he continued. “As the years went by I realized this day, and my arrest, would inevitably come.”

Mr. Madoff acknowledged that he had “deeply hurt many, many people,” adding, “I cannot adequately express how sorry I am for what I have done.”

His testimony was shaped not only by expressions of regret, but also by his determination to shield his wife and family.

As a result, those who thought his guilty plea would shed more light on Wall Street’s biggest and longest fraud left the courtroom unsatisfied and uncertain—about where their money had gone and who may have helped Mr. Madoff steal it. The hearing made clear that Mr. Madoff is refusing to help the government build a case against anyone else.

Repeatedly, Mr. Madoff insisted that the stock-trading business run by his brother and two sons was legitimate and untainted by his crime. That contradicted the criminal charges against him and statements made in court by Marc O. Litt, the federal prosecutor handling the case, who asserted that at times Mr. Madoff’s firm “would have been unable to operate without the money from this scheme.”

Mr. Madoff also claimed his fraud began in the early 1990s, not in the 1980s, as the government contends—an assertion that seemed aimed at limiting how far back into the family business history the government can reach for restitution.

No family members have been accused of any wrongdoing and they all—Mr. Madoff’s wife, Ruth, his brother Peter and his sons, Mark and Andrew—have denied any knowledge of the fraud. Mrs. Madoff is seeking to retain almost $65 million that she says are her own assets.

And when one of Mr. Madoff’s victims urged a public trial to shed more light on the crime, Mr. Litt promised that the government was vigorously investigating what had happened to the money and who else had been involved—questions that could have been answered by Mr. Madoff if he were willing.

“Did we get answers? Not at all,” said George Nierenberg, an award-winning filmmaker, whose family lost nearly everything to Mr. Madoff.

Mr. Nierenberg was one of a handful of victims that Judge Denny Chin of Federal District Court allowed to speak at the hearing. As he went to the podium, he suddenly turned to the defendant and prodded him to “turn around and look at the victims.”

For a moment, a startled Mr. Madoff did look at Mr. Nierenberg, before Judge Chin warned Mr. Nierenberg to address the court, not the defendant. “What I saw was a hollow, empty man,” the filmmaker said later.

The inconsistencies between Mr. Madoff’s version and the government’s charges are evidence that no plea agreement could be reached, said Joel M. Cohen, a former federal prosecutor in Brooklyn.

“Clearly, he’s light-years away from being cooperative,” Mr. Cohen said after reviewing a transcript of the hearing. “Essentially, Madoff is saying, ‘I’ll plead guilty—but I’m not going to plead guilty to exactly what you say I did.’”

But Thursday’s hearing probably is not the final forum for exploring Mr. Madoff’s crime. Typically, before sentencing, the court conducts what is called a Fatico hearing in which the government and the defense lawyers try to resolve factual disputes remaining in the case.

“While we do not agree with all the assertions made by Mr. Madoff today, these admissions certainly establish his guilt,” said Lev L. Dassin, the acting U.S. attorney in Manhattan, in a statement after the hearing. “We are continuing to investigate the fraud and will bring additional charges against anyone, including Mr. Madoff, as warranted.”

The 11 counts of fraud, money laundering, perjury and theft to which Mr. Madoff, 70, pleaded guilty carry maximum terms totaling 150 years.

After Mr. Madoff’s plea was accepted, his lawyer, Ira Lee Sorkin, tried to persuade Judge Chin to allow Mr. Madoff to remain free on bail, confined to his apartment on the Upper East Side, until he was sentenced.

Judge Chin refused.

“He has incentive to flee, he has the means to flee, and thus he presents the risk of flight,” Judge Chin said. “Bail is revoked.”

Some of Mr. Madoff’s victims began to applaud that ruling before Judge Chin cautioned them to remain silent. As Mr. Madoff’s hands were cuffed behind his back, some victims nodded with satisfaction.

And as he was led out of the paneled courtroom into an antiseptic tiled hallway, Adriane Biondo, of Los Angeles, wept with anger. Her family’s devastating losses have left elderly relatives “sick with fear,” she said. “It’s emotional—120 cumulative years of hard work is gone.”

Raw emotion had been an undercurrent throughout the day, from the moment Mr. Madoff arrived at the courthouse, and was ushered into a 24th-floor courtroom that was already packed with lawyers and victims.

Mr. Madoff stood, was sworn in and reminded that he was under oath. Noting that he had waived indictment, Judge Chin asked, “How do you now plead, guilty or not guilty?”

“Guilty,” Mr. Madoff responded.

Then the judge said, “Mr. Madoff, tell me what you did.”

Mr. Madoff began: “Your honor, for many years up until my arrest on Dec. 11, 2008, I operated a Ponzi scheme through the investment advisory side of my business, Bernard L. Madoff Securities LLC”

Mr. Madoff’s fraud became a global scheme that ensnared hedge funds, charities and celebrities. He enticed thousands of investors, including figures like Senator Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey, the Hall of Fame pitcher Sandy Koufax and a charity run by Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

The fraud’s collapse erased as much as $65 billion that his customers thought they had. It remains unclear how much victims will recover. A court-appointed trustee liquidating Mr. Madoff’s business has so far been able to identify only about $1 billion in assets to satisfy claims.

—March 13, 2009

NOTE: Madoff was sentenced in 2009 to 150 years in federal prison. Though others on Madoff’s staff or in his employ were convicted of having played some role in the fraud, neither his wife nor his sons were ever the subject of a criminal investigation related to the case.