We’re in a Special Period, one of the most difficult periods in our history. Why? Because we’re alone confronting an empire. Only a weak, cowardly people surrenders and goes back to slavery.

—Fidel Castro

Guillermo Rigondeaux is Cuba libre. That’s fighting for freedom from Cuba. He had to get on the boats, the rafts, and brave the hazards of the ocean and the shark-infested waters to seek freedom. Where did he seek that freedom? Old Glory right here. This is the only country in the world that people try to break in rather than to break out.

—Don King

If the choice between Cuba and America amounted to one between Fidel Castro and Don King, what kind of choice was that? This was boxing, one of the rawest distillations of capitalism America could dish out, always a poor man’s sport, so nearly every ugly question raised about this dynamic naturally had an even uglier punch line. Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t? Maybe, maybe not. Before you had the chance to choose between King or Castro, what about Cuba’s version of Sophie’s Choice: in this case, the choice between what dollar value America could offer you versus the risk of never seeing your family again? And that’s only if you made it that far. Pushing your chips into that decision required accepting estimates of the gruesomely high mortality rate of the people who had attempted to cross the same ninety miles Guillermo Rigondeaux traveled as human cargo, along with thirty other men, women, and children, back in February 2009.

It’s hard to move without a path. Rigondeaux stepped inside a smuggler’s boat and washed ashore into a perilous new struggle he knew very little about. Boxers have a notoriously limited shelf life. There was very little time for Rigondeaux to cash in on his talents. Rigondeaux’s only path to success was hurtling toward the American Dream like a runaway ambulance through traffic. All I knew to do was to get as close as I could and tail him toward my own version of it.

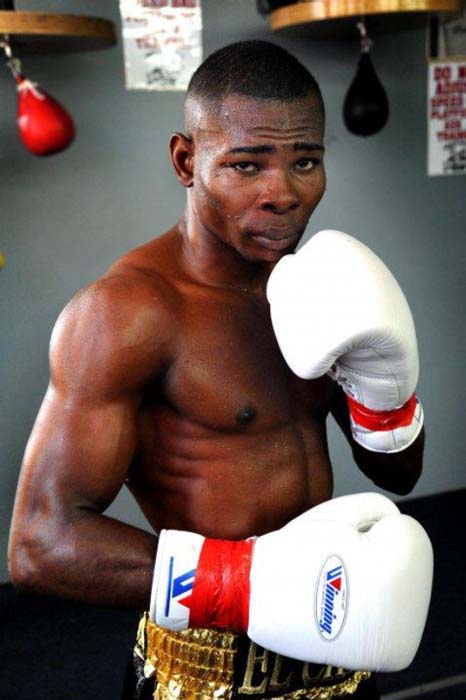

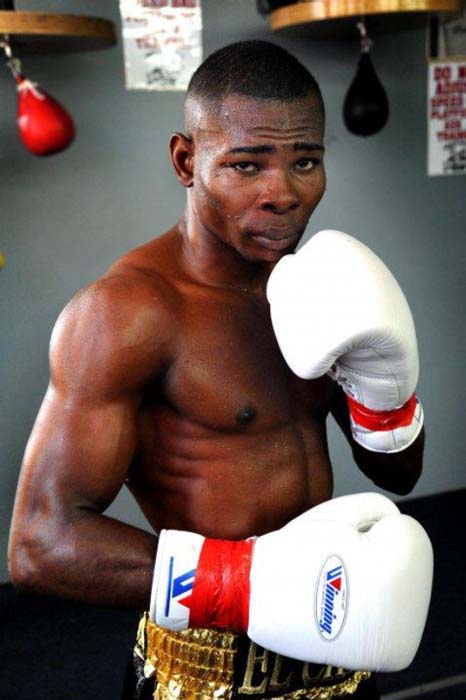

Which led me to a parking lot outside the Wild Card gym in Hollywood, California, waiting for Rigondeaux to arrive. I was checked in next door at the Vagabond Inn, where Rigondeaux had also stayed for a few days when he first moved to Los Angeles. It was the common first stop for all fighters who traveled to Hollywood, and most never earned enough in professional boxing careers to cover their hotel bills. I had an interview and a photo shoot scheduled that I’d arranged inside Wild Card, one of the world’s most famous gyms, where Rigondeaux had recently begun training. This was the gym where Manny Pacquiao, the most beloved boxing champion since Muhammad Ali, had trained for years. Pacquiao’s success had made Wild Card the most famous boxing gym on earth and had made his trainer, Freddie Roach, an international celebrity. A billboard down the street advertised Roach’s new HBO reality show.

After only a year fighting in America, Rigondeaux had blown through all five of his opponents, knocking out four. Freddie Roach had agreed to train Rigondeaux and told reporters that meeting the Cuban defector reminded him of the first time he’d met Pacquiao. “He’s the most talented fighter I’ve ever seen,” Roach had told me the day before. “But he’s up against a lot. And I don’t mean anything inside the ring. If he can stay in L.A. and avoid everything over there in Miami that seems to swallow up all the other Cuban fighters who come over, he can make it. But how many great stars from Cuba have come over here and made it? Being the greatest amateur fighter who ever lived doesn’t sell tickets in this country. Americans hate the Cuban style. And Florida won’t sell out the front row of a dance hall to watch their best Cuban fighters. It’s not going to be easy for this kid. Politics and sports—it’s fucked.”

It had taken me a year to figure out a way to reunite with Rigondeaux in America. The best I could come up with was ambush. I was broke and I didn’t know anyone he was dealing with in Miami, where he had lived since the defection in February 2009 until this recent move to Los Angeles to train. One of his backers in Miami was known as “The Spam King,” who had traded a life of selling cocaine in the 1980s for a life sending out more than a quarter of a billion spam e-mails, some of which were sex related, daily for the “legitimate” endeavor of getting involved with Cuban boxers.

When I read that Rigondeaux had moved to Los Angeles to sign up with Freddie Roach as his trainer at Wild Card, I finally had an in. While I wrote for nobody, had zero credentials, and had never formally interviewed anyone, the only friend I had in professional boxing was a recently retired female world champion who, during her title reign, also secretly moonlighted as a stripper in Las Vegas. She and I had both boxed amateurs in Canada at the same boxing club when we started out in the sport. After she won her first title, she had flirted with being trained by Freddie Roach. Roach had a crush on her and they had remained friends. She offered me Freddie’s phone number and an introduction. During the conversation with Roach over the phone, I lined up an interview with Rigondeaux at the gym.

Having no money to undertake the enterprise, I pitched the idea to a wealthy, flamboyant boxing client of mine who aspired to get into photography. Mucho Macho had just turned fifty, resembled some kind of bizarro, heterosexual Oscar Wilde in midlife crisis who drove a custom-made Japanese sport bike, and had just come back from a three-week visit to Havana, where he was “bitten by the place.” Cuba had greeted Mucho, as it greets many visitors, with open legs. I offered him a full-access photo shoot with Rigondeaux in exchange for him footing the expenses to L.A. “Very gonzo.” Mucho Macho laughed. “I’m up for an adventure.” The following day he showed up with our plane tickets and fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of camera and lighting equipment, and on the flight over we read the instruction manuals about how to use everything. One amateur teamed up with another on the hunt for the greatest living amateur on earth.

With its Hollywood location, Wild Card gym was a fascinating intersection of poverty and egregious fortune. Everyday Hollywood celebrities and people with vast wealth looking to be seen poured into Wild Card’s parking lot in their luxury automobiles. The gym was also the centerpiece of a mini-mall that included a barbershop, Laundromat, an Alcoholics Anonymous office, a Manny Pacquiao gift shop, and a Thai “happy ending” massage parlor for anyone having an unhappy afternoon of sparring at the gym. (People from the gym have told me that this policy has changed.) Across the street, just off Santa Monica and Vine, a stampede of destitute men and women, many strung out, crammed their way into a Social Security office to cash their welfare checks.

It had been more than a year since Rigondeaux’s second defection attempt from Cuba to the United States—this time successfully—via a smuggler’s boat to Cancun, in February 2009, and just over two years since I’d met him in Havana after his first failed attempt at defection back in Brazil during the Pan Am Games. After the arrest in Brazil, Rigondeaux had been sent back to Cuba in disgrace. Any hope he had of resuming his life and boxing career ended the moment Fidel Castro himself personally branded Rigondeaux a Judas and traitor to his people. Rumors were everywhere about how exactly he had managed to escape the regime with so much heat on him back in Cuba. There were rumors that he signed more contracts with people trying to get him out than autographs. Since arriving in the United States via Cancun, Rigondeaux had refused to give any details for fear of reprisal by the Cuban government against his wife and two children, who were still living there. The choice to leave had already lost Rigondeaux one family member: Rigondeaux’s father, a staunch Fidelista, had reportedly disowned his son for Rigondeaux’s betrayal of a revolution that specifically benefitted rural Cuban families like theirs who had suffered the worst under Fulgencio Batista. In order to escape Cuba, Rigondeaux was forced to abandon his mother, wife, and two children. Only very recently had reports out of Cuba announced that Rigondeaux’s mother, who allegedly supported his efforts to leave, had died. Rigondeaux was forbidden to return and attend the funeral under threat of immediate arrest.

At one time or another, only briefly in most cases, I’d met a handful of the most famous Cuban boxers who’d rejected millions to leave and seen both the rewards and the toll of that decision up close. They were routinely carted out at the national boxing championships to take a bow or they visited Rafael Trejo while I was training. I wanted to understand why someone like Rigondeaux, a Cuban meant to carry the symbolic mantle of Fidel’s half-century struggle against America, had rejected his role. If Bobby Fischer had fought the Cold War on behalf of the United States against Russia on a chessboard, Rigondeaux was meant to do the same thing for Cuba, only in a boxing ring. Rigondeaux never wished to be a symbol for anyone or anything. He did wish to be an individual. As he made his descent from hero to traitor, then transformed from martyr to exile, it was clear all he had ever wished to be was a boxer.

As the Hollywood sign peeked out from behind the smog, I couldn’t help wondering what impression this scene, this city—this country—had made upon Rigondeaux when he had first arrived. Guillermo Rigondeaux Ortiz was born on September 30, 1980, and had grown up on a coffee farm in Santiago de Cuba with six brothers and sisters. There was no running water in his family home, so one of his daily family chores was walking a few miles to load up on water and transport it back to his house. He credited this task in developing his phenomenal balance and strength. The same year Rigondeaux was born, one hundred twenty-five thousand Cubans departed the country during the Mariel boatlift, the largest exodus since the revolution began. Cuba’s economy had dropped sharply, and more than ten thousand Cubans crammed into the Peruvian embassy, seeking asylum. Fidel responded with an announcement that anyone who wished leave could do so openly. A massive exodus by boat ensued. “Fidel has just flushed his toilet on us,” Mauricio Ferré, the Miami mayor at that time, famously remarked. Rigondeaux, barely in his teens, had then been discovered for his potential by the Cuban industrial sports complex and had been sent to train in Havana at La Finca, the most elite sports academy on the island.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and with it an end to billion-dollar subsidies sent to Cuba, Rigondeaux spent the remainder of his teens during the worst of what Castro described as a “Special Period.” Cuba was in free fall, with widespread blackouts and overwhelming energy shortages. Food became scarce, along with any available fuel. By some estimates, the black-market economy eclipsed the size of the regular economy. People were serving time in prison simply for possessing an American dollar. Not long after the media firestorm of Elián González had been messily resolved with González being sent back to Cuba, Rigondeaux won his first Olympic gold medal in Sydney on his twentieth birthday. Whatever backdrop accompanied Rigondeaux’s rise in Cuban society, his living in Cuba would always mean never being permitted to emerge as an individual, let alone the superstar he felt himself to be, regardless of how much he accomplished. By Castro’s design, there was only one superstar in Cuba, and that was the system itself.

Rigondeaux loved cars. Like nearly all boxers—most of who come from profoundly impoverished circumstances—he was materialistic. Castro had given him a Mitsubishi Lancer, Cuba’s rough equivalent of a Bentley, after he won his second Olympic gold medal. (He was awarded his modest home in the Boyeros section of Havana for his first gold.) When the government impounded it as punishment after the alleged defection attempt in Brazil, Rigondeaux had told the media that it was his favorite possession in the world. Other Olympic champions, such as 1992 gold medalist Joel Casamayor, had famously gotten nothing more than a Chinese bicycle. Another champion and Rigondeaux teammate, Yuriorkis Gamboa, sold his gold medal to a tourist in the hopes of scraping together enough money for his daughter’s birthday party. Yet I wondered if those Range Rovers and Bentleys in Wild Card’s parking lot were enough to overshadow all the suffering felt by the people who actually lived in the area and had fallen through the cracks of a society only to hit bottom with no safety net.

*

“Where the fuck is this guy?” Mucho Macho asked me. “You’re sure you had an interview lined up?”

Finally a Lexus SUV pulled into the parking lot and slowed down where we were standing. The driver’s side window rolled down and a man shouting into his cell phone put his hand over the phone and waved me over.

“You’re both here for the interview with my fighter?” the driver asked in a thick Irish accent. “You’re here for Rigondeaux?”

I nodded.

“He’s not here?”

“Nope.”

“I was afraid of this. Sorry lads. Cubans—what do you expect? My apologies. I’m Gary Hyde, his manager, and this is my son Tommy sitting next to me here. I’m trying to work this out right now. I have Miami on the phone. Lemme just park this thing.”

For the next half hour we waited with Hyde and his son while Hyde fielded one tense call after another.

“Gimme another second, lad.” Hyde held up a hand apologetically and answered his phone for the tenth time, pacing away out of earshot. He returned and closed his phone. “The Miami crew says they don’t know where he is but he’ll be here. He’ll be here. What a disaster. Isn’t this gym grand, though? The whole city. I’d love to live in a town like this. Do you like it, lads?”

Hyde and his son had both flown in the previous day from Cork. Hyde was tall and broad, a former amateur boxer himself, with a crew cut grown out slightly above his forehead and a little of it curiously slicked up into horns. Yet anything imposing about his presence immediately evaporated the moment he interacted with his boy. Seeing them together, with Tommy not much older than the small son Rigondeaux had left behind in Cuba, I wondered what the toll would have been on Hyde’s life losing someone so precious to him.

Almost as soon as I met Hyde and mentioned that I’d spent a fair amount of time in Cuba as an amateur boxer myself, Hyde forgot the immediate hassle with Rigondeaux and was giddy to swap tales.

“I’m the first man in history to ever actually go over there and pull off getting any of the Cuban boxers out.”

“They’ve been getting out for years, haven’t they?” I asked. “Decades, actually. 1967 was the first defection.”

“No.” Hyde laughed. “I was the first to go to Cuba with the explicit intention of signing a boxer to a contract, paving the way with the smuggler’s boat crossing, and launching their career in the professional game.”

In fact, Hyde would later explain, he had gotten out four. Rigondeaux was the first he signed and the last to leave. The other three Cuban boxers who had escaped were now living and fighting in Ireland. However, Hyde no longer held their contracts. “They didn’t adjust well,” Hyde confessed. “In the ring, of course, they kept winning. But outside the ring they struggled to cope.”

“What happened to them?” I asked.

“Stopped training. Gained twenty-five pounds the moment they left Cuba. Attitudes changed. The sense of entitlement. You wouldn’t believe it, given where they came from. I mean—” Hyde stopped just short of calling it an outright betrayal. “Can you blame ’em though? They all want out of that horrible place and they expect to be fighting in front of fifty thousand people, making billions. Didn’t you see that over there?”

“Sure,” I agreed. “But most can’t imagine surviving without their family.”

“If I had my way,” Hyde said solemnly, “I would send ships and take everybody out. I really would.”

Hyde’s son grinned and shook his head. “He would, too.”

For a second things felt surreal, as if we were all on a Broadway stage, and I was waiting for father and son to break into an impassioned Disney musical number on saving Cubans and delivering them to the promise land.

“But the best boxers first?” I teased. “Is this business or altruism?”

“I already got the best of the boxers out,” Hyde corrected as his son nodded approval.

Where Americans were forbidden by law from facilitating the trafficking of anyone out of Cuba—including exceptionally talented athletes—Hyde capitalized on what he saw as a golden opportunity left to non-Americans like himself. The only risks involved were being locked up in a Cuban prison for perhaps upward of ten years per athlete you spoke with trying to line it up. During his trips, from what I could gather, Hyde had spoken to enough to spend the rest of his life in jail. He was fully cognizant of this also. Which raised an interesting parallel between Hyde and his favorite Cuban fighter: While Rigondeaux, with the desperation of a social pariah, had risked never seeing his family again in Cuba, Hyde, giving all the appearances of living in comfort, had risked the same with his own family to secure a champion.

Hyde’s phone rang again. This time he didn’t bother to wander off as the conversation escalated into another argument.

“They don’t know where he is,” Hyde said, jamming his phone in his pocket. “He’s fuckin’ AWOL. But I’m sure he’ll show. He has to show. He has a fight in less than two weeks.”

“What the hell gave you the idea to try this out?” I asked. “Getting out Cuban boxers over here, I mean.”

“This is fun.” Hyde laughed. “Way back I had my first professional show back in Ireland. I spoke to one Michael Flatley—”

“Lord of the Dance Michael Flatley? The dancer?”

“A dancer worth $640 million.” Hyde smiled broadly. “Like me, he’s a boxing nut. So after I had my show, Flatley said, ‘You’re missing a superstar in the making. Someone that we can all get a feel for and follow through to eventually winning big titles, especially world titles.’ I says, ‘Where you going to get one of them?’ He said, ‘Maybe go to one of the poorhouses of the world and get one.’ I t’ought”—Hyde giggled uncontrollably for a second—“Where else you gonna go? Why skip Cuba?”

Why skip Cuba? It was left hanging there in all its rhetorical splendor. Right then everything about Rigondeaux’s story eerily entered Broadway musical theater territory again. I felt as if I’d just listened to one of the starring actors relive his audition for the guest-starring role of Fagin, with Rigondeaux as his Artful Dodger. Michael Lewis, the author of Moneyball and The Big Short, among many other bestsellers, wrote his first feature for Vanity Fair, in which he called Cuban athletes the most expensive human cargo left on earth. Back in the 1990s, a Cuban American living in Miami named Joe Cubas had done it with baseball and was hailed by 60 Minutes as “The Great Liberator.” There was nothing written in the rules of baseball that said he couldn’t help Cuban baseball players defect, so Joe Cubas had devoted his life to the enterprise. Since then, venture humanitarianism across those treacherous ninety miles has never been more lucrative. If you could get athletes out, professional sports were offering bigger money than ever to put them on an American stage.

“Have you gone on the record about how you did this?” I asked Hyde.

“No.” He winked. This buoyant attitude Hyde had about his time in Cuba was something he clearly reveled in. “I been asked a million times for the story from loads of places, but I’m not sure if I want to tell what was involved. I took far, far too many chances doin’ it on me own.”

I looked around for Rigondeaux through the tunnel of the parking lot out to Vine Street and back to the entrance of Wild Card, where hordes of tourists were already lined up to buy T-shirts and take photos at the gym where Manny Pacquiao, the most famous fighter on earth, trained for his championship fights. Now Rigondeaux and Manny Pacquiao shared Freddie Roach as their trainer. The press had been largely dismissive of Rigondeaux or any Cuban fighter’s chances in professional boxing. They were cursed with a “boring amateur style.” They were too technical. They sought only to “score points and beat computers” rather than opponents. On the business side of things, Cubans were, by far, the hardest sell in the sport. Unlike Puerto Ricans in New York or Mexicans in California, Miami and the rest of America didn’t care enough to pay to watch Cubans fight. If baseball was a hard sell in Miami, which it was, fat chance with a marginalized sport like boxing. Yet when I asked Roach if Rigondeaux had the potential to become a professional champion, Roach countered that Rigondeaux, fresh off the boat, could have beaten several world champions on the same day.

And it seemed he was correct. Since leaving Cuba, Rigondeaux had breezed to victory in all five of his first professional fights. Outside the ring, however, Rigondeaux had struggled through a great deal of litigation with his management. After signing with Hyde, Rigondeaux had also signed a managerial contract with an attorney named Tony Gonzalez, who brought Rigondeaux to Cuban American promoter Luis DeCubas. I assumed issues related to that mess explained the heated discussions Hyde was having with the folks in Miami involved in Rigondeaux’s career.

Hyde told me that Rigondeaux was living in the small apartment adjacent to the entrance of Roach’s gym. Roach commonly let new fighters who had come to train with him in L.A. use the apartment until they found a place of their own. A Cuban restaurant up the street called El Floridita was where Rigondeaux had most of his meals. He didn’t go out at night, and his handlers from Miami had assigned an assistant to be with him at all times to keep an eye on things.

Hyde’s phone rang and he paced off and returned quickly, red-faced. “This is fucking ridiculous. Hyde looked at his watch and shook his head. Rigondeaux, Hyde confessed, had been AWOL since the night before. Something had happened during sparring the previous day. Rigondeaux had been battered by a teenaged Mexican amateur. Roach and Hyde had even filmed it. With a fight around the corner, Rigondeaux had arrived in Los Angeles from Miami on short notice, completely out of shape. He had been worked over so badly by the Mexican teenager that Freddie Roach had refused to work his corner in the upcoming fight. Rigondeaux’s people in Miami insisted he still fight.

“I’m his manager,” Hyde asserted. “Freddie Roach is his trainer. If his trainer refuses to work his corner on the basis that he’s in danger, I won’t let him fight. If I won’t let him fight, legally he can’t fight. That’s that.”

“Dad.” Tommy pointed.

“What, son?”

“There he is.”

Both Hyde and I looked and saw Rigondeaux and a goofy assistant in a Cuban Olympic tracksuit marching briskly through the tunnel toward us in the parking lot. Although Rigondeaux was wildly upset, screaming into his phone, his face was frozen and gargoyle-like. Before Hyde had a chance to say anything, Rigondeaux and his assistant swung over to the set of stairs leading to his apartment and sprinted up, slamming the door behind them. A moment later they emerged with some heavy gym bags slung over their shoulders and dragging luggage behind them.

“He looks like he’s not staying in L.A. long,” I said.

“No, he doesn’t,” Hyde agreed. “Let me sort this out.”

Rigondeaux approached us, ignored Hyde, shook my hand distractedly while muttering the traditional Cuban boxer salutation of “Campeón,” and then ordered his assistant to present me with a rolled-up poster. To break the bizarre confusion, Rigondeaux’s assistant smiled—offering a glimpse of the diamond-studded $ over his front tooth—and opened up the poster to show me Rigondeaux’s signature.

“Vamos,” Rigondeaux said under his breath.

“What’s going on here?” Hyde asked them. “We had an interview scheduled hours ago.”

“Miami,” Rigondeaux grunted icily.

“What?”

“Miami.”

Just then a taxi rolled up through the tunnel and popped its trunk. Rigondeaux and his assistant calmly turned, loaded their luggage, and got in. A moment later they were gone while Hyde, his son, and I stood speechless.

“Cubans,” Hyde lamented.

Over the next few days newspapers and Web sites reported that Rigondeaux was once again suing Hyde to break free of his contract, firing Freddie Roach, and pulling out of his upcoming fight with a minor injury.