I mean the fact that there’s even a market for Cuban defectors, to me, always seemed so perverse really. A whole market grew up around the geography and the politics, the supply and demand of these super gifted athletes.

—Steve Fainaru, Pulitzer Prize–winning coauthor of The Duke of Havana

Cuba has always been a treasure chest for outsiders obsessed with her loot. This didn’t change all that much as pirate ships gave way to the regular procession of cruise ships that enter Havana’s harbor today. During the nineteenth century, the American government offered vastly larger sums to purchase the island from Spain than they did for Louisiana from the French or Alaska from the Russians. It wasn’t for sale. The U.S. Treasury still issues an annual check for $4,000 to Fidel Castro for the lease on Guantanamo Bay, which no Cuban ever negotiated, and that can never increase or expire.

Back in 1492, Columbus described encountering Cuba as “the most beautiful land that eyes ever beheld.” Of course, this was just an unexpected detour from the real objective of his voyage. Fortunately, the Taíno island natives quickly brought everything back into focus for Columbus when they greeted their visitors with offerings of gold (which held no value in their society) and happily reported, when asked, of other areas where more could be found. Columbus promptly enslaved the natives and enlisted them to mine for any and all gold that could be seized and returned to Europe.

Columbus and his men also rounded up the Taíno wives and female children and sold them into sex slavery back in Spain. Once the remaining natives of Cuba fully understood that insatiable lust for the island’s natural resource was the reason behind Columbus and his men’s continued presence, they dispensed whatever gold they had into the sea in hopes of ridding the island of its intruders. Farther inland, where the sea wasn’t readily available, the Taínos found rivers to dump their gold in protest. By the 1530s, nearly all the Taínos were wiped out by a combination of genocide, slavery, starvation, suicide, and disease. Nearly five hundred years later, athletes like Rigondeaux had replaced gold as the most lucrative treasure Cuba boasted. History repeats itself with Cuba’s loot again entering the sea in protest, but this time the protest is in opposition to the original Taíno values—the ones that saw gold as worthless—now advanced by Castro’s government. These days, Cuba’s treasure wants to go where it can cash in.

*

“Did you ever hear about the Caribbean Queen?” Gary Hyde asked me. He was wearing a fine tailored suit for our joint voyage, just as we closed in on the U.S.-Mexico border, the busiest port of entry in the world. Our rental car settled into the general morass of border gridlock. “The most famous smuggler running people back and forth between Cuba and Mexico? The one Castro personally put a bounty on?”

“The most famous human smuggler was a woman?” I asked.

“Of course not. The Cuban army routinely shoot at smuggler’s boats and smugglers, but they have orders not to shoot at women. So the Caribbean Queen conducted his business in drag.”

Everything was getting weirder the closer we got to Tijuana.

I was riding in the passenger seat of the rental vehicle Gary Hyde had picked Mucho Macho and me up in from LAX. As we crawled forward, a sign out the window told us we had ten miles to go before the international border that divides San Ysidro, California, and Tijuana, Mexico. We had two hours before Rigondeaux had to weigh in at the Auditoro Municipal, thirty minutes across the border. Hyde kept fiddling with the radio while our suicide mission’s official photographer, Mucho Macho, suggested which lenses might be put to best use from ringside while he shot the fight.

“Any ideas, Gary?” Mucho Macho asked.

“Many ideas,” Gary replied calmly. “I’ll make sure to come over and discuss them with you after the two of us in the front seat aren’t assassinated in the fuckin’ ring during the fuckin’ Cuban national anthem before a few thousand Mexicans in the crowd and everyone watching at home on fuckin’ FOX Deportes.”

“Did you pay anything to Rigondeaux to sign your contract?” I asked Hyde. “Like a bonus or something?”

“You can’t ask for directions down there without expecting to pay.” Hyde laughed.

“How much did he want?”

I didn’t bother asking whether the contract was in Spanish so Rigondeaux had a hope of understanding its contents.

“Rigondeaux didn’t have so much as a bank account. But he was worldly enough to know with a contract there was a signing bonus. At the time Rigo was having some hassle with his wife. I asked him how many girlfriends he had. Instantly he says, ‘Seven.’ So I offered him ten dollars for each one.”

“You signed the greatest amateur boxer on earth for seventy dollars?” (In other interviews this figure has varied.)

“I handed over the money along with the pen and he signed right there.”

“If this guy was born in any other country on earth how much would he have signed for after his first gold medal at the Olympics? What, ten thousand times that amount?”

“But he wasn’t from any other country. He was from Cuba.”

“Yep.”

“But I kept sending him money after that until he was ready to leave. A lot of money, too.”

*

Before Rigondeaux, the most famous defection in Cuban history by an athlete was when Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez escaped the island on Christmas Day 1997. After nearly thirty years of being banned by the state, the Christmas holiday had been reinstated that same year at the pope’s request. Hernandez was the most successful pitcher in the history of Cuban baseball. American agents and scouts had salivated for years over El Duque’s potential. They shadowed his movements around the world as he pitched for the powerhouse Cuban team internationally. However, Duque was known as a true believer. He had every chance to leave with a vast fortune awaiting him. As inferior American pitchers like Kevin Brown signed contracts with Major League Baseball for $105 million, El Duque survived on $105 a year. With his prime fading, staring down the million years it would take to earn the same amount in Cuba, Hernandez defended his reasons for remaining on the island with arresting statements like: “I know the prettiest word in the world is ‘money.’ But I believe that words like ‘loyalty’ and ‘patriotism’ are very beautiful as well.”

However, after Livan Hernandez, El Duque’s brother, abandoned Cuba, it was Duque who was left to face the music. He was banned from picking up a baseball on any field in the country. He was banned from even stepping on any baseball field. “I don’t know why they’re doing this to me,” Duque said at the time. “I’ve had every opportunity in the world to defect and I never did…. I don’t know why I have to pay for my brother’s sins.” Finally, after years of loyalty, Hernandez was finally pushed too far and defected. Fidel had found it in his heart to pardon Santa Claus, but no pardon was offered to the revolution’s most successful pitcher. Yet even after signing for millions and winning the World Series with the New York Yankees in his first year in the United States, Orlando Hernandez would always maintain, despite the immense hardships he faced in Cuba and even after the state’s betrayal, that he never wished to leave.

The specifics of El Duque’s escape quickly became a big-fish story with the American media. There were dozens of versions. New sensational details were added to the myth with each telling. Sharks gnawed at the raft. The little fishing boat took on water the minute it left Cuba and nearly sunk. Biblical storms thundered as the ocean roared and heaved. Certain death was avoided only after El Duque himself took a makeshift oar and rowed his way to freedom. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner would even claim that Duque had left the island in a “bathtub.” All these myths naturally made El Duque even more marketable in New York, sold more jerseys and newspapers, put more asses in seats, and upped the ratings on television.

S. L. Price attended El Duque’s first press conference in Miami. It was at this same press conference that Price watched Hernandez cry uncontrollably as he reunited with his brother Livan for the first time in America. As most journalists penned their cover stories of an American Dream triumphing over the same stale Cuban nightmare, Price remembered the moment differently in his book Pitching Around Fidel: “Mine is an unseemly standoff between head and heart, a logical mess. I applaud Duque’s escape, but I’d rather see him pitch in Havana…. I know what everyone knows: Cuba is the worst place on the globe to be an athlete today. But I’m sure I know something even stranger. It is also the best.”

After the World Series victory, Fidel Castro, against expectations, agreed to make the remarkable gesture of putting Duque’s mother, ex-wife, and two daughters on a plane to reunite with him. It was just in time to have them join Duque and his team for the ticker-tape parade marching up Broadway’s “Canyon of Heroes.” After that year there were three more World Series victories for Duque, millions more earned, and a comfortable retirement in Miami that he devoted to working with children and introducing them to baseball to offer what he could to help them succeed.

Of course there was an interesting catch to all this. When Ray Sánchez and Steve Fainaru, for their book The Duke of Havana, caught up with Orlando Hernandez at the height of El Duque mania in New York, he was living in a lush hotel on Lexington Avenue. “The room was stuffed with gratuitous perks of El Duque’s new fame: designer sunglasses, compact-disc players, unwrapped sweaters, athletic shoes, cigars—boxes and boxes of free stuff. ‘Look at all this,’ he said finally to Sánchez. ‘Look at how much I make, and I get all this shit for nothing. You make a fraction of what I make, and you can’t afford it. There’s something wrong there. There’s something wrong with this system.’ Sánchez asked him what he meant. El Duque backed off. ‘Ah, you’re still better off here,’ he said.”

To reinforce the ambiguity of his legacy, Duque maintained his assertion that despite all his newfound riches and the Hollywood ending of being reunited with his family, had Castro not forced him out, he never would have left. All reporters I interviewed about El Duque—S. L. Price, Steve Fainaru, and Ray Sánchez—who had known him closely on both sides of the Florida Straits, confirmed that Hernandez in America was an irrevocably changed man from whom they’d met in Havana. And not for the better.

*

And let’s have no displays of indignation. You may not have known, but you certainly had suspicions. If we’ve told lies you’ve told half-lies…. And a man who tells lies—like me—merely hides the truth. But a man who tells half-lies…. has forgotten where he put it.

—Mr. Dryden from Lawrence of Arabia

*

“Can I push record now?” I asked Gary Hyde, our progress toward Tijuana stymied by another traffic jam, this time at the border.

“When it comes right down to it, in Rigondeaux’s story I’m probably the best of a bad lot …”

George Orwell once pointed out that all the characters of Dickens, unlike Tolstoy, have one thing in common: no inner life. None of his characters grow. Tolstoy’s characters are “struggling to make their souls, whereas Dickens’s are already finished and perfect.” It’s impossible to imagine having a conversation with a character from Dickens. It’s impossible to imagine them straying from their script. No interior life exists with his characters. “They never learn, never speculate,” Orwell goes on to explain. “Tolstoy’s characters can cross a frontier; Dickens’s can be portrayed on a cigarette card.” I wanted to learn from Hyde’s dealings in Cuba which camp Hyde identified with.

In the past, the architects who helped Cuban baseball players escape the island had been hailed as “liberators” by conservative hardliners in Miami and much of the American media, who supported tightening the embargo against Cuba even further. They were praised for having assisted in destabilizing Castro and the evil regime where it symbolically hurt. The policies behind the embargo still made sense to many of these people, while others saw politics as little more than a smoke screen for what amounted to venture humanitarianism. El Duque, at his lowest, most desperate point after Castro came down on him, reached out to Cuban American Joe Cubas, who had helped Duque’s brother Livan Hernandez escape. Cubas, bitter about the fact that his exorbitant fees had exploded his relationship with what he deemed an ungrateful Livan, is quoted in The Duke of Havana as having replied, “Let that nigger drown.”

Right at the outset during Hyde’s interview, it was obvious we were wading into the deep end of human nature with a fascinating undertow of denial.

“Can we start from the beginning?”

Hyde nodded.

As I pressed record on my iPhone and lay the device inside the rental car’s cup holder, Gary Hyde began to unfold his adventure of hunting down the best of the nearly twenty thousand boxers officially employed by the state to fight on the island of Cuba:

*

Gary Hyde: Back in 2007, Michael Flatley saw a show I put on back in Ireland. He liked the show but told me, “You’re missin’ a superstar in the making. Somebody we can all get a feel for and follow through to big titles, especially world titles.” I said, “Where you gonna get one of them?” He says, “Maybe go to one of the poorhouses of the world and get one.” So I thought, where else would you go? Why skip Cuba? [Laughing.] That was February 17, 2007. By the beginning of March I was in Cuba.”

Brin-Jonathan Butler: That was the first time you’d seen him?

G.H.: I first saw him on television, like everyone else, when he won gold at the Sydney Olympics in 2000.

B.J.B: When did you first meet him?

G.H.: The 2001 World Championships in Belfast, where he won the bantamweight championship. I met up with him personally there. He snuck off from the team with a few others and we met in a pub. The Cubans were always a big attraction. I was keeping an eye on the Cuban team. They were all there lined up in a row from one weight class to the other. Like sitting ducks. Rigo just kind of shouted out to me. Very, very special like. He was just a baby, twenty years old. And, of course, no human being could want to stay in that system. But they never said at that time that they wanted to leave.

B.J.B.: Did you have an idea then about getting involved with Cuban fighters?

G.H.: [Laughing.] The same idea I had of getting out Félix Savón. I’m sure anyone involved in boxing would say, “I’d love to have a Cuban like that as a professional.” But it was just way out there. I never thought I could have put a plan like that, you know, into motion. I wasn’t out to prove any point. I wanted these fighters. Nothing was going to stop me.

B.J.B.: So after Michael Flatley suggested Cuba, you were there by March of 2007. During that month between him suggesting it and you going, what was your research into trying to figure out, I dunno, “How am I going to do this shit?” Nobody had ever done it before, right?

G.H.: I’m the first. My research into how I was gonna do it didn’t start until I had a chance to talk with those kids. First I met the kids in Havana, got a feel for them, and after that I started looking into a plan about how to get them out.

B.J.B.: How do you find the best boxers in Cuba?

G.H.: It was actually really easy. I found an interpreter who found the Finca [the top boxing school in all of Cuba] and contacted Rigondeaux at the Finca, and he arranged to meet us. We met him, didn’t spend too much time with him. He knew what we wanted from him straightaway. But we never told him if he was right or wrong at first. That happened a few days later. Rigondeaux was the first one I met. All boxers over there were very paranoid. I met Rigo in Central Park in Havana. He had a swagger, everyone was stepping out of his way. There were obviously huge risks involved. But I never paid attention to them.

B.J.B.: How did you start that conversation?

G.H.: I told him I was a writer working on a book doing research about Cuban fighters. That was my angle over there, that was the angle I was going at. He said, “Professional boxing?” He was on it straightaway. He knew straightaway what was really going on.

B.J.B.: Did he ask for anything in order to make that happen?

G.H.: No, he was kind of reserved the first week I was there.

B.J.B.: Where did everything go from there?

G.H.: I got nervous and got to thinking he could be a little too big a fish in his little pond and maybe get us into trouble. He was a bit wiser than what I thought I would be working with. He was twenty-six then. So I looked at some other boys at the Finca instead.

B.J.B.: Had anyone made an attempt to help Rigondeaux, up to that point, to get him out?

G.H.: Nothing that I knew of. Nothing reported or on record, as far as I know.

B.J.B.: What were the risk of going into Cuba and trying to do this? What happens if this goes wrong?

G.H.: Being incarcerated by Fidel indefinitely, I suppose.

B.J.B.: But you decide to do it anyway.

G.H.: It was an adventure. For me it was just an adventure. I was out of my mind that I wanted three or four fighters—Rigo number one. I wanted to manage them in Ireland, run up a brilliant record, and bring them back to the U.S. for HBO and championships and all that.

B.J.B.: Rigondeaux and everyone else over there live in desperate circumstances. This risk at least makes sense for them to make. You’re successful. You’ve been married twenty years with kids. Why are you risking so much for this?

G.H.: When I want something on my mind, I get it. I saw Rigo and I done it. Put my family to one side because I never really believed I’d get caught. I was cute enough in the way that I done it. Thinking back on what I did, it was very, very dangerous.

B.J.B.: Knowing what you know now of the risks, would you do it again?

G.H.: [Shrugs.] In a heartbeat.

B.J.B.: Were there risks even if you succeeded from Miami? Before smuggler’s boats and all that, all the Cubans who’d escaped had gone there, presumably because people there were funding people to get out, no?

G.H.: I didn’t worry about none of that. I knew I could get him fights. I knew I could get him a good stage. The only risks, as far as I cared, were logistics. Logistically my problem was just getting him from his island to my island, Ireland. I never even dreamed of him wanting to go to the States no matter who was there. Even after a few days Rigo was very friendly with me. All the boxers I met down there clung to me. They were more interested in my relationships with them than becoming champions in pro boxing. I was, you know, coaxing them into the boxing side more.

B.J.B.: Logistics.

G.H.: I was, like, sitting on the Malecón one day looking at the moon and thinking, like, this is the same moon that I look at when I’m looking up in Ireland. How can I get from here to there without going through airports, without going through security? There must be a way. I researched everything. I researched from going there on a raft, going there on a speedboat, going there in a submarine, a Jet Ski—I tried everything I knew. All we had to do was get them twelve miles, once you were twelve miles off the coast of Cuba you were in international waters. You were safe enough. I didn’t think about the consequences after that. I just wanted them out of Cuba. Rigondeaux, and a couple other fighters I had my eyes on at that point, were being financed by me. I was sending money there regularly. If I sent five hundred euros over there, it cost me one thousand euros because of how hard it was to get money there. I sent money in sports books, through DHL. I’d have a five-hundred-euro note glued in on page seventy-nine, enclosed, and once he got it he was to call me. DHL wouldn’t deliver money for you, but they’d deliver a book. That kinda stuff. It was all kind of cloak-and-dagger stuff, really. It was just so slow and difficult to get money over there. But the feeling I had inside me, the minute the money was offloaded and collected? The feeling I’d get the minute I knew when they got the money? The feeling I had when they got their hands on the money and the unbelievable feeling of achievement that they were so comfortable now and they were so happy with me. It just binded us together even more. It’s hard to kind of explain it. If I sent one thousand euros and it came back to me, I’d have been gutted. But if I’d sent one thousand euros and I’d phone ’em and hear their whole family cheering, “Miguel! Miguel! Miguel, you’re the best!”

B.J.B.: Miguel?

G.H.: They all knew me as Miguel down there. That was the name I traveled under. But when everything worked out and they had the money I’d feel like the greatest person in the world. This is an achievement that they’d collect my money and everyone is happy and the emotion from that lasted—well—it lasted for the length of that phone call. [Laughing.]

B.J.B.: What other ways did you send them money?

G.H.: I left my daughter’s debit card with them. They’d take out money and I’d fill it back up in Ireland.

B.J.B.: What happens next?

G.H.: By April I was under unbelievable pressure from these boxers to get them out. I was always expecting to hear sirens and the security coming after me. Even with the money I kept sending all of them the pressure built up. When I went back to Cuba I was stopped at the airport. I had brought all kinds of gifts, you see. They knew something was up. But I got through. I went to see Rigo at his house. I think it was his house. It had all kinds of trophies and medals. I think it was. Every Cuban refers to every house they step into as their house, whether it’s their brother-in-law or their cousin or their friend. But I think it was his house. Everything was getting very dangerous. I was staying at the Habana Libre, what used to be the Havana Hilton until Castro took over. Every time I came down from my room to make a call at reception, I saw security make calls. They was just standing normal until they saw me then made calls every single time they saw me. I’d supplied three different boxers I was looking at down there with cell phones but I was getting scared down there.

B.J.B.: And what’s Rigondeaux doing during all this?

G.H.: He’s stalling. I’m still paying him. I have my contract but, like they say, contracts can’t fight.

B.J.B.: Where does Mexico enter this equation?

G.H.: Human smuggling is a fifteen to twenty-billion-dollar-a-year industry down there.

B.J.B.: Second to drug trafficking.

G.H.: Now it’s many of the same people.

B.J.B.: Diversified their portfolio.

G.H.: Drug traffickers charge smugglers a price per person for the right to cross over their territory.

B.J.B.: “Derecho de piso,” I read. Right of passage. Or they abduct the migrants and hold them for ransom.

G.H.: Messy business. This was all happening in Cancun. Eight people had been murdered over it just before I got there. Turf wars. Of course I didn’t know one person, not nobody in Cancun. I had nowhere to go. But I knew it was happening there in Cancun. Surely I’ll see a boat down there with a Cuban flag or whatever. I met someone down there, over the period of five days. A cabdriver. He knew where there were some Cubans living who were well-respected Cubans. I went down there, met those people. There was a gate. It was like a terrorist house with bars on the gate. I told him I wanted to get my friend out. He said, “I dunno what to say to you or who to tell you to go to.” I told him I was staying at the Cancun Palace. So he came over with his wife and his daughter and stayed with me for three days. He’d come over and unload my minibar in a suitcase and bring it home while being pissed drunk the whole time, too. After a few days he tells me he can deliver a boxer from Cuba. So I connected them to a boxer and they found him.

B.J.B.: Not Rigondeaux?

G.H.: He wasn’t ready yet. Still stalling. And at this stage I know everything about the waters between Cuba and Jamaica, Cuba and the Bahamas, Cuba and Miami, Cuba and the Cayman Island. I called after two days and they said my boxer could see Mexico from where he was in the boat. He couldn’t come ashore because they saw a navy boat from Mexico and they were waiting. Then I got a phone call and he made it. I talked with him. I got on a plane and picked him up in Cancun.

B.J.B.: This was the first boxer in history smuggled out of Cuba on a speedboat?

G.H.: Yes. I put the same people onto Rigondeaux. I got my work permit for him to get to Ireland, which would assure him a visa after he landed in Mexico. At the time I was doing this, several Olympic teammates of Rigo’s escaped by speedboat. None of them sent a dime back to Rigo. I had contacts in the Mexican underworld I was sending money through over to Rigo in Havana. I lined up a contact in Cuba to wine and dine Rigo to make a decision about leaving finally. This was all leading up to what happened at the Pan Am Games in Brazil in the summer of 2007, when he tried to leave with someone else and all that shit exploded. Rigo claimed he was drugged and drunk. He was found with hookers in Brazil. He denied signing or having any interest in leaving. He told that to Fidel and the press and he told that to me.

B.J.B.: You believe that?

G.H.: Doubt it. He went to the embassy over there in Brazil, where they had visas for him. As we’ve seen since, regardless of who actually got him out, I had my contract.

B.J.B.: Why didn’t he leave in Brazil?

G.H.: He wasn’t willing to make the jump. Rigo was hopelessly paranoid about security everywhere.

B.J.B.: So he’s the most politically radioactive person when he’s sent back in disgrace to Cuba. How the fuck do you get him out now?

G.H.: They took away his car. They would have taken away his house but for his family. He put on a lot of weight. He smoked. Wasn’t training. Everyone he knew was banned from talking to him. Everyone had to stay away and keep a wide berth. But he was still on my money drip. He was being looked after. But he was very isolated in Havana, though of course he was under constant surveillance, twenty-four-hour surveillance. He was very frustrated. He tried to get on as a coach for the Beijing Olympics. But Fidel said he was a traitor.

B.J.B.: Did Rigondeaux ever approach or push you about getting his wife and two kids out?

G.H.: I didn’t offer him this until 2008. I had to dangle a carrot to him. Of course I didn’t want the wife and the child out. I wanted him to get out and make his own money and then bring them out. I didn’t want to finance a wife and a child and then Rigondeaux. Let’s say they all get to Cancun and he has a passport and visa to come and work in Ireland but does he have the papers to prove she’s his wife? That is child is his child? What if that wife and child get stuck in Cancun? With Rigo and the work permit I had, I could get him his visa from any Irish embassy in the world within an hour. I learned enough in twelve months that you would learn in twenty years about the regime and getting out of Cuba. Everything. You had the “white cards,” marrying foreigners, the lottery in Cuba for an exit visa, and so forth along those lines.

B.J.B.: But he wasn’t leaving.

G.H.: Six weeks I had a man with Rigo every day trying to lure him out. I had a boat on twenty-four hours’ notice to leave. Still, every day, Rigo refuses to go. All through 2008, Rigo turned on at least twenty Cuban boxers to my contact to get them smuggled off the island using Miami money.

B.J.B.: What happens when these people get smuggled out?

G.H.: They get picked up quietly by a van or a trailer and taken to Pinar Del Rio. Big dangers. Boats break down. Pieces missing. They get shot at by police or the army. In Cancun they get locked up in windowless rooms until the money is paid over. It’s tense because COD doesn’t mean cash on delivery, it’s cash or death.

B.J.B.: How many people would Rigondeaux be traveling with on a smuggler’s boat?

G.H.: Normally thirty-four or thirty-six people. Normally.

B.J.B.: Men, women, and children?

G.H.: Men, women, and children. Yeah.

B.J.B.: He leaves Cuba through someone else and escapes to Cancun in February of 2009. When is your last contact with him?

G.H.: November 2008 was the last time I sent him money. A couple grand. I was starting to get itchy feelings Rigo was trying to sign with someone else. My contact said to me over there, “Jesus Christ won’t get Rigondeaux out. If Jesus Christ is here, he won’t get Rigo. Rigo is coming to you. You set us up with Rigondeaux and he’s coming to you.

B.J.B.: Somebody else got him out.

G.H.: Like everyone else, I saw the news he got out in February of 2009. He came out on my boat. I didn’t pay for it, though. He used my boat with someone else’s money.

B.J.B.: Had you negotiated a price to get Rigo out at that point?

G.H.: Fifty thousand dollars for Rigo, his wife, and one of the kids. That’s the price I negotiated for them.

B.J.B.: Who got him out?

G.H.: He’d signed a professional contract with Arena Box-Promotions. Presumably they got him out. I immediately filed suit, seeking an injunction prohibiting Rigondeaux from competing until the terms of my contract were upheld with him fighting for me.

B.J.B.: And you won in court.

G.H.: Indeed. And here we are at Tijuana, lads. Let’s park and start over on foot.

*

We parked the rental at the border, took a collective deep breath, and started across the border on foot as if walking the end of a plank toward Tijuana. The fenced-in path climbed toward a meat-grinder turnstile entrance beneath a sign announcing MEXICO. I could see nobody guarding the entrance. Once we were through the meat grinder, the path began a winding descent down a ramp toward a pair of armed Mexican marines standing near a seemingly barren “inspection area” with the most surreal traffic light I had ever seen: It had a button that we all took turns pushing, receiving an approving green glow in response. Everything about entering Tijuana seemed to nightmarishly suggest “What could you possibly smuggle into this place that we don’t already have?”

We walked down some stairs toward some chain-smoking taxi drivers slumped against their cars. Gary marched over and announced “Auditorio Municipal?” to the least sinister-looking of the group, and we got in the cab. After a couple of minutes we took a bridge over the Rio Tijuana and turned onto Avenida Revolución toward Rigondeaux’s weigh-in. Stopped at the first traffic light on Tijuana’s main strip, we saw soldiers straddling massive artillery they had pointed at the street, standing behind sandbags piled up to neck level. Waiting for the light to change, I looked up the street and saw Tijuana’s version of Cirque du Soleil, with two kids flipping cartwheels in between two lanes of traffic blowing by at forty miles per hour. Over and over again these lunatics spun and whirled, not a cigarette’s clearance between them and the cars blurring by on either side. A few blocks later we passed what seemed to be the same impromptu checkpoint set up with the artillery and sandbags.

“So far, so good?” Hyde elbowed me in the ribs and straightened his tie.

*

Outside the weigh-in being held at the Auditorio Municipal, we saw disgraced local boxer Antonio Margarito surrounded by Mexican reporters and photographers laughing off his banishment from boxing. Before a fight against former world champion Shane Mosley, a substance similar to plaster of Paris was discovered in Margarito’s hand wraps. He was suspended for a year from boxing, only to return to the biggest payday of his life with a shot against Manny Pacquiao at Cowboys Stadium in Dallas. If Rigondeaux won the following night, Hyde had mentioned Rigo would have his own title shot on that undercard. Ultimately the ugliness associated with Margarito’s cheating only increased his marketability.

Once we got inside the lobby of the arena, fighters were scattered around waiting their turn on the scales and a once-over from a doctor to clear them to fight. Among all the reporters and entourages, I couldn’t find Rigondeaux anywhere. The atmosphere inside the room was full of canned laughter, say-cheese smiles, and backslapping. Managers and promoters mugged for cameras with their fighters and recited sound bites to reporters whose faces lit up when they heard the one they’d run with on that evening’s telecast. Hardly any Americans anywhere, mostly Mexican and Latin American fighters looking to break into the American market with a big performance. I watched teenagers with their lives in front of them and a pipedream intact avoid the sad journeymen who also waited their turn on the scales. Eager young fighters on their way up, old fighters double-parked in their careers looking for one last payday to stave off their fate of being another footnote in punch-drunk history.

All the serious fights I’d seen up close until that point were in Havana, where some coaches from the Havana provincial team allowed me to sit ringside with their fighters at the Kid Chocolate arena. It was where I first saw Rigondeaux fight. Back in the 1920s, the eponymous Kid Chocolate (real name Eligio Sardiñas Montalvo) used to fight in the Havana streets as a boy for loose change. At twenty-one, he became Cuba’s first world champion. He ran around with so many women that he had to defend his championship numerous times while battling syphilis. The first time I walked into Chocolate I didn’t even know fights were taking place, and I entered midway through a provincial tournament. They didn’t have enough money for a bell to clang to announce the fights or declare the beginnings or ends of rounds, so they used an emptied fire extinguisher and a rusty wrench instead.

Cuban eyes often look close to tears. For me the most apparent trait of the national character is an unbearably proud, sore heart about what it it means to be Cuban. Tears are never far away because their pain is always raw, but so is their joy in equal measure. Kid Chocolate was my gateway drug into that joy. How many socialists does it take to change a lightbulb? We’re not going to change it. We think it works. My high school gym had more money sunk into it than the most famous arena residing in Cuba’s capital city named after a troubled hero. It was clear that nobody fighting was paid to fight any more than you or anyone else had paid to watch. Cigar and cigarette smoke curled into the rafters as bottles of rum were passed around in the audience and swigged. It was packed and at first I assumed everyone was forced to attend these matches the same way seven-hour Fidel speeches invariably had hundreds of thousands of bored, annoyed, nodding-off citizens in attendance at the Plaza de la Revolución. However, I didn’t find that here, even though the faces carried the same strain from all that was going wrong outside Chocolate. At first what I was looking at didn’t even register as Cuban, but rather an American conservative’s wet dream of sport: everything playing out under the emblem of sport being “pure,” as it was back in the golden era of grandpa’s time. Although nobody here could keep score with money in the same way you could back home, everything certainly still seemed to count.

No interviews. No cameras. No advertising. No commercial breaks. No merchandise. No concession stand. No thanking of sponsors. No luxury boxes. No Tecate or Corona ring girls. No autographs. No VIP seating. No scalpers outside. No parking lot or parking meters outside. No venue named after a corporation or corporately owned anything, anywhere. No air-conditioning or even fans to mitigate how fucking hot it was in the afternoon heat. No—just proud people everywhere. People fighting harder in the ring than anywhere else I’d ever seen for people in the stands who cheered louder than anywhere else I’d ever heard. Nothing separated them. They might have lived on the same block. Sport was no opium for these people; Cuban culture was the opium of sport. If van Gogh captured the world’s imagination in part for never being able to sell some of the most treasured works of genius, it’s important to remember he was still trying to. Castro’s culture went further and they knew it: The magic of everything Cuba represented was in their heroes not being for sale. Then they started leaving, just like Rigondeaux.

*

Rigondeaux’s name was called over a P.A. and Hyde pointed him out to me, grabbing my arm. Rigo was sitting quietly in the corner of the room on a folding chair when he noticed us approaching. He had on the same Armani T-shirt that he wore when I first met him in Havana. When he saw Hyde he offered his hand to shake but made a point of staring away from his face. I stood off to the side and watched them hug awkwardly while Rigo leaned over and whispered something in Hyde’s ear. When they pulled away from each other Hyde nodded and smiled politely, saying to his boxer, “After. After the weigh-in. After.”

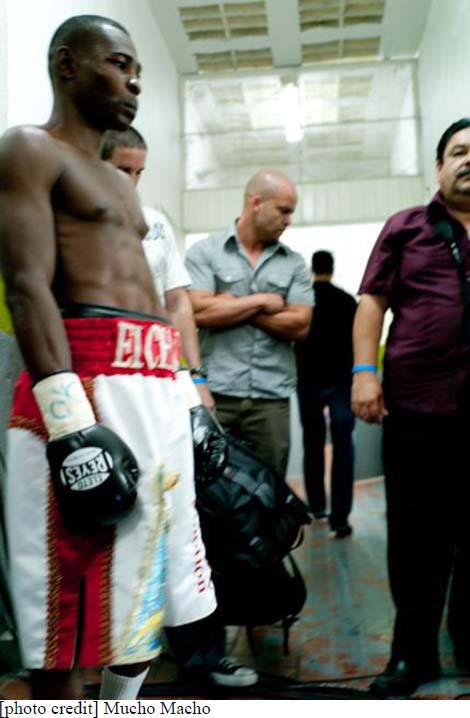

Rigondeaux got undressed and handed his clothes to Gary Hyde as he stepped on the scale. A few members of the Mexican media took his photo, but most weren’t that interested in him. Rigondeaux’s sixth professional opponent, Jose Angel Beranza, a sorrowful-looking, diminutive Mexican with thirty-two wins and eighteen losses on his record, watched the proceedings in his underwear before his turn arrived.

Hyde came over and grumbled to me, “Rigo wants more money. Same story every time I see him.”

After Rigondeaux had his clothes back on, I approached him and wished him luck in his fight the following evening. He sullenly shook my hand, avoided eye contact, and thanked me.

I asked him about an interview and the expression on his face turned severe as he tilted his head to one side.

“Claro.” He flashed the gold in his mouth—a sudden grin. “How much money did you bring, campeón?”

I looked over at Hyde and back to Rigondeaux. I shrugged, and Rigo smiled again and told me we could talk back at his hotel. He signaled to Hyde that he was ready to leave and began to walk toward the door while a few photographers called out to him. Rigondeaux offered a fist in their direction as we followed behind him, caught a taxi outside, and left for the nearby hotel where the fighters were staying. Nobody said anything in the taxi while Rigondeaux fiddled with his new iPhone. Bobby Cassidy, a kind and generous reporter I’d contacted in New York who interviewed boxers in Cuba, had sent me footage he’d captured of Rigondeaux wearing an I LOVE NEW YORK sweatshirt and using the same iPhone to film Times Square the night before a fight on Broadway. Beneath the stock ticker, double-decker buses, and billboards, he looked less like your typical tourist than like a man floating off into the capitalist abyss.

Rigondeaux had the saddest face I’d ever seen in Cuba, yet looking at it in that cab, I saw it had clearly hardened into bitterness since he’d arrived in America. It seemed as if Rigondeaux’s Greek tragedy in Cuba had simply found a new stage in America. Homer, the first boxing writer in history, wrote of Achilles sacrificing marriage and a happy but unremarkable (and forgotten to history) life for the tragic immortality that awaited him in Troy. The etymology of Achilles’s name comes from the Greek words akhos for grief, and laos, meaning a people, a tribe, a nation. Achilles chose to live a cursed existence. Rigondeaux looked as if he knew something about that state of being as he resembled more and more a gargoyle pried off Fidel’s monument of Cuban sport.

I wasn’t sure leading up to our interview whether Rigondeaux’s Troy amounted to the world championship title or simply the riches that came with it. Maybe he wanted to bring his family over with that money, and maybe he didn’t. A lot of hugely successful Cuban athletes escaped with the help of their families back home only to turn their back on them the minute they arrived in the United States. (S. L. Price explored that angle in Pitching Around Fidel with Rey Ordóñez’s escape and subsequent success as a shortstop with the Mets in Major League Baseball). Others moved mountains to reunite with their loved ones, as El Duque had. Of course, maybe Rigondeaux wouldn’t even get that far.

After we got to the hotel, Rigondeaux ordered a Coke from the bar and joined me at a table with Gary Hyde. His security handler from Miami agreed to translate for our interview. A waiter brought Rigondeaux a well-done steak from the kitchen and two other staff members politely asked if they could have their photos taken with him. He posed with his fist raised for both photos and sat down across from me, leaning over with his elbows over his knees.

“Do you feel the revolution betrayed you or did you betray the revolution?” I began.

Rigondeaux jumped out of his chair and stood over me like a soldier called to attention. “I’m not a traitor! I did not betray my country. I went back to Cuba from Brazil. I did not betray my country. I returned. If I had known they would never let me box again in Cuba, I would not have returned and none of this mess and scandal would have happened.”

“So your intentions in Brazil were never to defect?”

“No.” Rigondeaux shook his head sullenly. “I would have stayed.” He sat back down in his chair and held out his open palm to me. “Now I’m going to ask you a question. When I came back from Brazil, what did all of my accomplishments count for? You are not Cuban, so I want you to answer me that question. Because they prohibited all the athletes to even come near me. Anyone who dared talk to me knew they would be sanctioned.”

“Your story sounds very similar to Héctor Vinent’s.”

“That’s the problem in Cuba. You can be the biggest thing at a given moment and at the same time you are nothing.”

“Nothing?”

“You are the same as everyone else. You are a champion and it means nothing. You don’t have a dollar and you have to walk everywhere because most of us don’t have cars or houses. We are like dogs. After all your time is over you end up telling stories on a street corner about when you used to be a star.”

“Is it true that Teófilo Stevenson defended you against Fidel?”

“Yes,” Rigondeaux answered, knocking the arm of his chair with his knuckles and holding up the same hand. “We spoke with the comandante together to see if he would give me another opportunity. I’m grateful for that with my life. The comandante said no.”

“Did Fidel betray you?”

“A traitor is someone who goes to war and runs away. This is sport. I never turned my back to fight against Cuba or anything like that. A traitor is someone who goes to war and changes to the opposite army. That’s a traitor.”

“What were you fighting for in Cuba?”

“In Cuba what can you say? You have to say for your country and the revolution because if you say something else they take you and hang you so you can’t say anything else.”

“I understand the official version. But for you, what was it that you fought for?”

“I fought so that I could get a house or a little car. There is nothing bigger to get in Cuba. Maybe being able to buy a little bit of clothes.”

“Most Cuban boxers are afraid to talk about their lives back in Cuba.”

“A lot of stuff I really feel I can’t say because I have a family and I’m here and I can say whatever I want, but they are still in Cuba and they would be the ones to pay for it.”

“After Brazil, when you were sent back to Havana, were the police following you?”

Rigondeaux laughed and shook his head. “Everywhere I went. When he came”—he pointed to Hyde—“I couldn’t enter a hotel with him. I had to stay in the lobby. The best fighter in Cuba couldn’t enter a hotel. Imagine that. I had a nice Mitsubishi Lancer, like the one in The Fast and Furious, which they took away from me. I earned it for my Olympic medal. They didn’t take my house, but only because I had my wife and children. Otherwise they would have taken that, too.”

“Is America what you expected it to be?”

“I have fought four hundred seventy-five fights and never made a dollar. I have fought all my life. I’ve seen the world because of my fighting.”

Rigondeaux held up his iPhone and laughed. “In Cuba you could work ten years and still not be able to afford this phone. This phone is worth seven hundred dollars, and where are you going to find seven hundred dollars in Cuba? In Cuba if you have a million dollars you can’t go to a car dealership and say, “I want a Mercedes,” because they are going to arrest you and take away that money. They will want to know where that money came from. Here if you have the money you can get what you want with no worries.”

“Does it ever scare you that someone like Mike Tyson could make and lose four hundred million so quickly here?”

“I came here to succeed and help my child in Cuba and my family so that is never going to happen to me.”

“Were you scared coming here?”

“I left behind all of my family. Here you have to stay on top of things or you will get eaten by the lion. The United States is the best country in the world without a doubt, but the real best country in the world is Cuba. You know why? Because you don’t have to pay rent, or pay for water, electricity, or for education. You don’t have to pay for hospitals. Here you can buy a house, but if you don’t have the money to keep paying you get kicked out. In Cuba that doesn’t happen.”

“Do you miss Cuba?”

“I fought four hundred seventy-five fights for Cuba. I fight for Cuba now. I haven’t lost a fight in ten years. Twice I’ve won a hundred fights in a row against the best amateurs in the world. I could have become the first man in history to win four Olympic gold medals. What would that have gotten me if I’d stayed in Cuba? Nothing. After I was done, like a drunk on a street corner, I would be asking people whether they remember when I used to fight when I was a champion. I would end up just like Héctor Vinent. You saw him. That’s how he is now.”

“What’s the most important thing about Guillermo Rigondeaux’s story?”

“I got here when everyone thought I was dead and the Cuban government figured I was their trash. They figured I would never attempt to escape again. They laughed about that. But I’m here. That’s what most inspires me. In Cuba when you win all you get is a handshake from Fidel and that’s it.”

“How do you feel about Fidel now?”

“I can’t say anything about that. I have family in Cuba. My thing is sports. That’s politics. All I can say is that anybody can make a mistake, but it shouldn’t cost you your entire life like it did for me.”

“If Cuba changed would you go back?”

“I would go right back to Cuba.”

*

The next day we crossed the border back into Tijuana and waited with Rigondeaux in one of the arena’s private dressing rooms at the end of a long corridor. The preliminary fights were already going on and the crowd was already noisy. Being in the room felt like being inside a burst blister—all the paint on the walls was scratched and scraped and the flooring chipped and gutted. The place stunk. It wasn’t all that different from dressing rooms in Cuba. It was located at the end of a tunnel that intersected with another main artery, descending like a plank toward the curtain separating the fighters from the audience.

Rigondeaux paced, relieving tension with little flicks of his arms or gentle kicks in the air. He kept his head down and looked up only to offer a face as blank as a dial tone. He’d done this hundreds of times before and it showed. Hyde had told me on the way down to the fight that if Rigondeaux beat his opponent here, his next payday in Dallas would increase more than sixfold, up to $125,000. Maybe that was on his mind.

As the minutes drew nearer to his sixth professional fight against Jose Angel Beranza, Rigondeaux’s new trainer, Ronnie Shields, asked him to come over and sit down to have his hands wrapped.

On a whim, I leaned over to Gary Hyde and whispered, “So who was this mystery kid who fucked Rigondeaux up in sparring back in L.A.?”

“Freddie Roach had never seen him before. I’d never heard of him. My son filmed the whole thing and so did Freddie with the security cameras. He wasn’t great or anything. Just brave.”

“And he was just some amateur from Mexico off the street?” I asked.

“Might have been sixteen. Soft. Nothing special about him in the least.”

“How many people were there watching?”

“Regular afternoon crowd. Whoever this guy was, he just didn’t seem to give a fuck about any double Olympic champion. He walked into Wild Card and pointed to Rigo—maybe he didn’t know who he was—and said he wanted to fight. He might have been a little bigger but not much. After the second round Rigo was gassed and this Mexican looked like he was in a Rocky movie. Freddie came over after and says, ‘Someone might have been exposed today,’ but Rigo was just not in shape.”

“And nobody ever saw this Mexican again? Nobody caught his fucking name?”

“Not that I know of.” Hyde shook his head. “I should have signed the fucking kid right there on the spot. Wait—”

“What?” I asked.

Hyde looked past me down the hall and squinted. “I t’ink your man is right t’ere at the opposite end of the tunnel.”

I looked fifty feet down the tunnel but saw only some chubby little Mexican kid standing next to a gym bag, putting on some gloves I assumed were his dad’s.

“Where?” I asked frantically. “I only see that kid.”

“Dat’s him.”

“No.”

“Yep. Dat’s him. How freakish a coincidence is that?”

I spun around and pulled Mucho away from taking photographs of Rigondeaux and pointed at the kid down the hall.

“Get some photos of that kid! He’s the one from L.A.!”

I watched Mucho race down the hall and wave like a maniac to get the kid against the wall of the corridor to pose for a few shots.

“You’re sure that’s the fucking guy?” I asked Gary.

“It’s him. No shadow of a doubt.”

I hadn’t been very subtle about this discovery. Gary elbowed me in the ribs, and I turned my attention back to our dressing room. Rigondeaux was glaring down the hall at Mucho taking this kid’s photos. Whether or not he identified the kid as easily as Gary had, he wasn’t pleased with what was going on. He clenched his jaw and cast a dirty look in my direction before Shields finished taping his gloves and asked him over to warm up in a little volleyball court behind one of the doors. Maybe this would be my last time covering one of Rigondeaux’s fights.

A few minutes later, a production assistant from FOX Deportes, the network broadcasting the fight, notified Rigondeaux that his fight was up. Everyone on the team gathered behind him as he lifted the hood of his robe over his head and stared down the plank leading to the curtain. It was the first time I’d ever seen Rigondeaux in person look peaceful.

Gary Hyde had a taxi with the engine running outside the arena as our getaway. After six rounds enduring Rigondeaux’s placid symphony of assault, Jose Angel Beranza simply quit. Rigondeaux dropped him twice in the fourth round. Rigondeaux coasted to victory and was booed every round by the Mexican audience. Deafening chants of “Bicicleta! Bicicleta! Bicicleta!” protested Rigondeaux’s textbook Cuban style of methodically picking apart his opponent and shielding himself from all risk. At the same time that Rigondeaux’s arm was raised in victory, we snuck out of the arena and raced back to the border into San Diego.

“Still alive.” Hyde grinned. “It’s quite a jump from here, lads. Next up, my first title on the Pacquiao undercard in Dallas, on the world stage.”